Abstract

At the micro-scale, the water exchange in karst water-bearing media remains unclear. This study applies the Stokes-Brinkman equation to couple the seepage within the karst matrix and the free flow within the karst conduit. The digital core technology is employed to characterize the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix and quantify its hydraulic properties, establishing a numerical model of water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit at the micro-scale. The results reveal significant differences in the hydraulic properties of distinct matrix samples, highlighting their key role in the water exchange process. Visualizations of flow velocity distribution and pressure gradients provide insights into the characteristics of the water exchange interface. A linear positive correlation between the exchange flow and the flow velocity of the conduit inlet is investigated, which can be attributed to the hydraulic head difference between the matrix and conduit. Additionally, the study demonstrates that the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix notably influences the water exchange compared to the homogeneous model. This research offers a new perspective on water exchange in karst water-bearing media at the micro-scale, providing valuable insights for optimizing the prediction and management of karst systems by understanding the multi-scale mechanisms of water exchange.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Karst water-bearing media is formed by the dissolution of soluble rocks, enabling them to store and transport groundwater. According to the theory of karst dual media, Karst water-bearing media is divided into the matrix and the conduit1. The matrix comprises primary pores and micro-fissures, characterized by low hydraulic conductivity but high storage capacity, with internal water flow typically occurring in a laminar manner. In contrast, the conduit consists of karst fissures and conduits, serving as the primary pathways for groundwater flow, where turbulent flow often prevails2. Water exchange occurs between these two domains, driven by hydraulic head difference and permeability difference between the matrix and conduits3,4. Due to the complexity of the void structures in karst water-bearing media and the distinct characteristics of the matrix and conduit domains, it is of great significance to investigate the water exchange in karst water-bearing media considering the scale effects of karst systems.

Current research on the water exchange in karst water-bearing media at the macro-scale primarily relies on field experiments to evaluate variations in water exchange and their corresponding responses5. For example, the hydrodynamic relationship between matrix and conduits is explored by long-term monitoring of rainfall and runoff fluxes in karst aquifers6. At the meso-scale, studies on the water exchange in karst water-bearing media often involve laboratory experiments and numerical models7. For instance, Shu et al.8 developed a physical model and a corresponding numerical model for fissures and conduits to investigate the spatio-temporal variability on water exchange. Furthermore, karst dual-flow models, such as those based on the Stokes-Darcy and Stokes-Brinkman equations, are widely used to study water exchange at both macro-scale and meso-scale9,10. The above research indicates that macro-scale studies of water exchange primarily rely on field observations, while meso-scale studies focus on laboratory-based physical models. However, the study of water exchange in karst water-bearing media at the micro-scale is very scarce. Because of this, in contrast to these more macroscopic scales, our forthcoming micro-scale water exchange research will focus on the pore structure of the matrix, which can be analyzed through digital core technology.

In karst water-bearing media, the matrix usually refers to the rock structures that have not been significantly dissolved or destroyed. In recent years, the rapid development of digital core technology, which uses high-resolution imaging and numerical simulations to analyze rock properties at the pore scale, has provided a new perspective for the study of rock structure characteristics11. For example, Zhou et al.12 conducted CT to construct digital cores and indicated that the reservoir space is composed of fractures and micropores, which is a dual pore system. Moreover, the permeability of the low-permeability glutenite reservoir is greatly influenced by pore structure. For another example, Kling et al.13 utilized a medical X-ray CT to observe single flow in a fractured sandstone, showing that preferential flow pathways with low tortuosity and stress-induced changes in fractures significantly impacted permeability. These findings underscore the capability of high-resolution digital core technology to facilitate the characterization of micro-heterogeneous rock structures. Furthermore, the pore structure and fractures within the rock have a profound impact on water storage and exchange.

High-resolution digital core technology provides an effective means of acquiring detailed structural information of karst water-bearing media, laying the foundation for advanced simulations of hydrodynamic processes. The discontinuous medium simulation is widely employed to model such hydrodynamic processes, particularly in karst systems14. This method assumes distinct transitions between different regions, such as the matrix and conduits, and relies on specific equations to describe fluid behavior in these domains. The seepage within the matrix is represented using Darcy’s law, which models flow in porous media, while the free flow within the conduits is described by the Navier-Stokes equation, and the Beavers-Joseph-Saffman boundary conditions are then applied to simulate water flow variations at the interface between the matrix and conduits15. In reality, however, the water flow velocity and pressure gradients between the matrix and conduits transition gradually rather than abruptly, contrary to the assumptions of discontinuous medium simulation16. To address this, the Brinkman equation, as an extension of Darcy’s law, integrates the Navier-Stokes equation to better capture the transition between these two domains. Particularly, the Brinkman equation effectively accounts for the shear stress effects of water flow, making it a valuable tool for studying the variations in flow velocity and pressure gradients in karst systems17.

Due to the micro-heterogeneous structure of karst water-bearing media, there are spatiotemporal variations in water exchange between the karst matrix and conduits. This study aims to establish a numerical model of water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit by the Stokes-Brinkman equation, with the characterization of the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix through the digital core technology, devoted to clarifying the influence of hydraulic properties of the matrix on the water exchange and reveal characteristics of the water exchange interface, also the dynamic process of the water exchange at the micro-scale. This study introduces an innovative approach by integrating the digital core technology with the numerical model, the heterogeneous model further highlights valuable insights into the microscopic mechanisms governing the water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit. These insights contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the water exchange in karst water-bearing media across multiple scales, providing a theoretical basis for the efficient development of karst groundwater resources18.

Methods

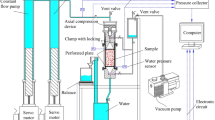

CT scanning experiments and digital core reconstruction

The rock samples selected for CT scanning experiments were sourced from the Baotian Tunnel in Guizhou, China. The sampling area belongs to the Lower Triassic stratigraphic unit, with all rock samples classified as the pure carbonate karst water-bearing rock group. As illustrated in Fig. 1, Samples 1 and 2 were obtained from deep and shallow boreholes excavated during tunnel construction, respectively, while Sample 3 was collected from a natural cave along the tunnel’s path. Sample 1 was taken from a depth of approximately 60 m, Sample 2 from about 20 m, and Sample 3 from the surface layer of the cave’s aquifer formation. Before CT scanning, all samples underwent an extended period of ventilation and drying. CT scanning experiments were performed using the GE V|tome|x S240 X-ray micro-computed tomography scanner (the China Chongqing Chromatography Technology Co., Ltd.), shown in Fig. 1d, which mainly comprises a micro-focus X-ray source, a high-contrast flat-panel detector, and a three-dimensional visualization analysis software. The main scanning parameters include a working voltage of 400 kV, a working current of 220 µA, and an exposure time of 500 ms per image. At the beginning of CT scanning, the sample is secured with a holder to ensure stability, then the sample is rotated at specific angles for continuous imaging during the scanning. This scanner enables high-resolution, non-destructive imaging of the void structures of the sample, utilizing X-rays to perform layer-by-layer scans. As the X-rays penetrate the rocks, their structural features absorb the rays, converting them into grayscale image data. The pixel of the two-dimensional slice image obtained by the device is 2048 × 2048, and the scanning resolution is 95.5 μm. A total of 1980, 1956, and 1675 two-dimensional slice images were obtained by scanning Rock Samples 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Due to the low quality of two-dimensional slice images obtained from CT scanning experiments, a series of image processing steps are required to accurately capture the three-dimensional void structures of these rock samples, including image cropping, filtering, and threshold segmentation, which are illustrated by taking Rock Sample 1 as an example. Firstly, all the two-dimensional slice images were imported into AVIZO software, and a cubic core with an edge length of 550 voxels was extracted, reducing the computational load with a smaller dimension, as shown in Fig. 2a. Next, the various image filtering methods were tested to process the image noise which is inevitably introduced during the CT scanning, finding that the median filtering ensured the best image clarity and integrity, and a comparison of an image before and after denoising is shown in Fig. 2b. To extract the void structures in the images, it is necessary to separate void structures from the matrix portion. Farzaneh Rezaei et al.19 researched the threshold segmentation for CT images of carbonate rocks and found that Otsu’s method achieved relatively better results. Consequently, this method was employed in this study for threshold segmentation, as shown in Fig. 2c, and the blue regions in Fig. 2d represent the void structures that were successfully extracted from the matrix of the core sample. These regions correspond to the areas identified as voids based on the segmentation threshold, effectively distinguishing the void spaces from the surrounding matrix material. Finally, the void structures were classified, resulting in multiple sets of connected and labeled pore structures, as shown in Fig. 2e.

Numerical model of the water exchange

Simulation conditions

This study aims to investigate the water exchange in karst water-bearing media at the micro-scale by coupling the seepage within the matrix with the free flow within the conduits. COMSOL Multiphysics software offers an efficient platform for modeling the interaction between fluid flow in open channels and porous media connected to the channel walls10,20. Recognizing the dual-structure characteristics and complex flow dynamics inherent to karst systems, a numerical model of water exchange was developed using the “Free and Porous Media Flow” interface in COMSOL, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Its predefined multiphysics interfaces and porous media flow options enable a detailed simulation of the interactions between the matrix and the adjacent conduit, offering valuable insights into the mechanisms driving water exchange under varying conditions. To ensure computational efficiency and analytical clarity, the model design incorporated the following settings and assumptions:

-

Model Configuration: to effectively analyze the characteristics of the water exchange interface between the matrix and conduits, the model was configured with the matrix directly adjacent to the conduit. Both components were modeled as rectangular blocks, a geometric choice that facilitates characterizing the matrix’s micro-heterogeneous structure.

-

Matrix and Conduit Dimensions: matrix samples with a dimension of 1.91 cm × 1.91 cm × 4.78 cm (200 × 200 × 500 voxels) were extracted from rock samples to represent the matrix portion of the model, and all matrix samples in this study are of this dimension. On the other hand, the karst conduit is designed as a single channel and a dimension of 1.91 cm × 1.91 cm × 7 cm.

-

Steady-State Assumptions and Water Properties: the simulation was conducted under steady-state conditions, with water considered incompressible at a standard temperature of T = 20 ℃. The physical properties of water were set to a density of 1000 kg/m³ and a dynamic viscosity of 0.001 Pa·s.

-

Boundary Conditions: the water inflow and outflow are set on two opposite sides of the conduit, with all other boundaries defined as no-slip walls effectively modeling realistic flow constraints. The interface between the conduit and the matrix is defined as a permeable boundary. The inlet boundary condition is specified as the groundwater flow velocity (V0) at the conduit entrance. The outlet boundary condition is established as static pressure (0 Pa), which can be approximated as atmospheric pressure or zero reference pressure, thereby reasonably simulating actual conditions.

-

Interface Continuity Conditions: at the interface between the matrix and the adjacent conduit, conditions for continuity of normal velocity and stress were applied to simulate the water exchange driven by pressure gradients and differences in permeability21. Specifically, at the water exchange interface, the seepage velocity within the matrix is equal to the velocity of free flow within the conduit, and the transmission of stress is continuous.

Fundamental equations

The numerical simulation of water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit is based on the Stokes-Brinkman equation. The free flow within the conduit is described by the steady-state, incompressible continuity Eq. (1) and the Navier-Stokes Eq. (2)16:

µ represents the water dynamic viscosity (Pa·s), u is the flow velocity in the conduit (m/s), ρ is the water density (kg/m3), and p is the water pressure (Pa).

The seepage within the matrix is governed by the continuity Eq. (3) and Brinkman Eq. (4) modified by the Forchheimer formula22

Here k represents the matrix permeability (m2), and εp is matrix porosity (dimensionless). The last term on the right side of the equation gives the Forchheimer correction term, which refers to the resistance contribution of turbulent flow. If the Forchheimer correction is not performed, the flow resistance in the matrix domain will be underestimated22. Moreover, Eq. (5) is the equation of dimensionless friction coefficient, and the additional resistance is realized by the Forchheimer coefficient (kg/m4)21 :

As illustrated in Eqs. (2) and (4), the momentum transfer is closely related to both matrix flow and conduit flow. The left-hand term of the Navier-Stokes equation corresponds to convective momentum transfer in the conduit flow. In contrast, the Brinkman equation replaces this term with resistance encountered by water flow through the matrix.

Characterization of the microscopic heterogeneous structure of the matrix

In karst water-bearing media, the heterogeneous distribution of pore structure governs the flow pathways of groundwater. Therefore, characterizing the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix in the numerical model of water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit can more accurately reflect the water exchange, thus providing a more realistic representation of natural karst environments. To emphasize the significant role of the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix in the water exchange at the micro-scale, a homogeneous model and a heterogeneous model were designed based on the characterization of the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix, facilitating comparative analysis of the research findings. Porosity and permeability, as parameters reflecting the characteristics of pore structure, typically determine the hydraulic properties of the matrix and the groundwater flow within it20. Additionally, considering the parameter settings of the “Free and Porous Media Flow” interface in COMSOL, permeability and porosity are chosen to characterize the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix.

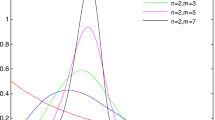

The homogeneous model does not characterize the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix, instead defining the pore structure of the matrix using equivalent permeability and porosity. The heterogeneous model, on the other hand, characterizes the matrix’s micro-heterogeneous structure by constructing interpolation functions for porosity and permeability. Specifically, the pore structure of the matrix is uniformly divided into multiple equal-volume matrix units. The porosity and permeability of each unit are then calculated by AVIZO software, and the center coordinates of each unit are recorded. The porosity and permeability of each unit, along with its coordinates, are integrated and imported into the model through the interpolation function. Through multiple comparisons, it was found that as the number of units into which the matrix is divided increases, the micro-heterogeneous effect of the matrix’s pore structure becomes more pronounced. In this study, considering the dimension of the matrix sample and computational efficiency, all matrix samples are evenly divided into 20 units, each with an edge length of 1.91 cm (100 voxels). Taking a matrix sample extracted from Rock Sample 1 as an example, Fig. 4a and b illustrate the spatial cross-sectional distributions of porosity and permeability within the matrix. The dimensions presented in Fig. 4 are intended to illustrate the dimension of the matrix cross-section and the spacing between the cross-sections. By incorporating both porosity and permeability, this approach allows for a quantitative representation of the matrix’s microscopic heterogeneous structure to a certain extent.

Results and discussion

Influence of matrix hydraulic properties on the water exchange

To investigate the influence of matrix hydraulic properties on the water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit, regions with relatively concentrated pore structures were selected from each rock sample. Three representative matrix samples were randomly chosen (i.e., the pores within the matrix have a certain degree of connectivity), totaling nine samples. The porosity and permeability of each matrix sample were calculated using AVIZO software, as detailed in Table 1. Firstly, taking Matrix Sample 3 as an example, a detailed analysis of its hydraulic properties was conducted. Figure 5a shows the connected pore structure of this matrix sample, with the calculation indicating that 95.1% of the total porosity is connected. Such high pore connectivity suggests that most of the pores within the matrix can serve as effective pathways for groundwater flow, allowing groundwater to flow relatively easily within the matrix23. Next, pressures of 0.13 KPa and 0.1 KPa were applied at the bottom and top of the matrix sample along the Z-axis direction, respectively, to simulate the seepage of groundwater within the pores. The absolute permeability of the matrix sample was then calculated to be 6.29 × 10⁻⁹ m² based on Darcy’s law24. Figure 5b shows the significant non-uniform distribution of groundwater flow pathways within the matrix, reflecting the crucial role of the matrix’s pore structure complexity in governing water flow. Figure 5c shows the pressure distribution during seepage. It can be observed that the seepage pressure decreases gradually along the flow direction, which reflects the resistance and energy loss encountered by groundwater as it seeps through the matrix.

The above analysis underscores the decisive influence of the pore structure within the matrix on its hydraulic properties. This not only deepens our understanding of water flow dynamics within the matrix but also lays a solid foundation for further exploration of the water exchange mechanisms between the matrix and conduits. To continue investigating the influence of the matrix’s hydraulic properties on the water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit, this study simulated water exchange based on homogeneous and heterogeneous models using matrix samples with varying hydraulic properties, as detailed in Table 1. Specifically, Table 1 records the significant differences in porosity and permeability among the matrix samples, parameters that directly quantify the diversity of hydraulic properties. In the design of the numerical simulation experiments, all other hydraulic conditions were strictly controlled to remain consistent. The groundwater velocity at the conduit inlet was set at a constant V0 = 2 m/s, and the exchange flow was calculated based on the normal flow velocity at the water exchange interface. Figure 6a visually presents the findings of the numerical simulation results: whether using the homogeneous or heterogeneous model, the exchange flow varies significantly under different matrix sample conditions. Notably, compared to the heterogeneous model, the exchange flow calculated in the homogeneous model is generally higher. However, despite the differences in the specific values of exchange flow, the overall trends are highly consistent across both models.

(a) The exchange flow varies under different matrix sample conditions. (b) The variation of the exchange flow with the increase of V0; (c) the variation of the hydraulic head difference between the matrix and the adjacent conduit with the increase of V0; (d) the variation of the exchange flow with the increase of the hydraulic head difference.

The findings highlight that the hydraulic properties of the matrix further regulate the water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit, primarily attributed to the differences in matrix porosity and permeability. In the results above, the differences in exchange flow observed between the homogeneous and heterogeneous models can be explained by the complexity of the pore network within the matrix. In the heterogeneous model, the intricate and dispersed flow pathways lead to more flow resistance, thereby reducing the overall efficiency of water exchange. In contrast, the homogeneous model assumes a uniform distribution of the matrix’s hydraulic properties, failing to capture the actual constraints imposed by the complexity of the pore structure on flow pathways and permeability. Although the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix significantly affects the efficiency of water exchange, it does not fundamentally alter the basic trend of how the matrix’s hydraulic properties regulate water exchange. This suggests that, while the structure of real karst systems is more complex, the mechanisms by which matrix hydraulic properties influence water exchange apply to both simplified models and models that more closely mimic real karst environments.

Characteristics of the water exchange interface and the dynamic process of the water exchange

In the subsequent simulations, Matrix Sample 9 from Table 1 was utilized to characterize the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix. When V0 was specified as a given value, the normal velocity distribution and pressure distribution at the water exchange interface between the matrix and the adjacent conduit are visually presented. Figure 7a and c show the interface velocity distributions for V0 equal to 2 m/s and 9 m/s, respectively. It can be observed that, in both the homogeneous and heterogeneous models, the interface velocity is not uniformly distributed, exhibiting local variations in velocity. Regardless of the magnitude of V0, the local variations in velocity are more pronounced in the homogeneous model compared to the heterogeneous model. Furthermore, based on the numerical differences in interface velocity, it is evident that bidirectional flow occurs between the matrix and the adjacent conduit at the water exchange interface in both models. However, the overall interface velocity is higher in the homogeneous model than in the heterogeneous model. This indicates that the water exchange occurs in both models, but the introduction of the matrix’s micro-heterogeneous structure results in differences in interface velocity between the two models. In addition, Fig. 7b and d present the pressure distributions at the water exchange interface for V0 equal to 2 m/s and 9 m/s, respectively. It is evident that, regardless of the magnitude of V0, the interface pressure in both the homogeneous and heterogeneous models decreases gradually along the flow direction, forming a gradient.

To further investigate the dynamic process of the water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit, the exchange flow under different V0 conditions was calculated for both the homogeneous and heterogeneous models. During the simulations, all other hydraulic conditions were kept constant. As shown in Fig. 6b, the exchange flow exhibits a linear growth trend with the increase of V0. This linear relationship is highly significant in both the homogeneous and heterogeneous models. However, within the same V0 range (0 to 10 m/s), the exchange flow in the homogeneous model is noticeably higher than that in the heterogeneous model. This indicates that, although the fundamental linear relationship between V0 and the exchange flow is consistent across the two models, the micro-heterogeneous structure of the matrix significantly influences the magnitude of the exchange flow. To further explore the intrinsic mechanism by which V0 affects the water exchange, the hydraulic head difference between the matrix and the conduit was calculated for each V0 condition in both models. As illustrated in Fig. 6c, the hydraulic head difference between the matrix and the adjacent conduit increases with V0 in both the homogeneous and heterogeneous models. Furthermore, Fig. 6d demonstrates that the exchange flow increases significantly with the hydraulic head difference. This result aligns with previous studies on the water exchange at a more macroscopic scale4,8, further confirming that the hydraulic head difference between the matrix and the conduit is the primary driving mechanism for water exchange.

This study reveals the characteristics of the water exchange interface between the matrix and the adjacent conduit at the microscale, specifically the local variations in the normal flow velocity at the water exchange interface and the gradient distribution of interface pressure. The simulation results also demonstrate that changes in the inlet velocity of the conduit induce variations in the hydraulic head difference, which in turn drives the dynamic process of the water exchange. However, the characteristics of the water exchange interface and exchange flow are significantly influenced by the matrix’s micro-heterogeneous structure. In the homogeneous model, the more pronounced local variations in interface flow velocity and the higher efficiency of water exchange can be attributed to the assumption of homogeneity, which reduces the resistance to groundwater flow. In contrast, the presence of the micro-heterogeneous structure in the heterogeneous model disperses flow pathways more realistically. Moreover, the consistent gradient variation in interface pressure observed in both models highlights the universal mechanism of energy loss during flow. This research quantitatively analyzes, for the first time, the critical role of conduit inlet velocity as a driving factor for the water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit. It unveils the dynamic mechanisms of water exchange at the microscale and confirms the consistency and applicability of the hydraulic head difference as the driving mechanism across different spatial scales.

Limitations and extensions

Karst matrix has a complex micro-heterogeneous structure, but its pore structure is difficult to characterize in physical models. The heterogeneous model developed in this study, while closer to realistic karst structures, still simplifies the complexity of pore networks and flow pathways. Nevertheless, the application of the heterogeneous model helps reduce biased understanding of water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit at the micro-scale, and to some extent, introduces realistic karst environmental features into the model, making the research findings more practically relevant.

The water exchange mechanisms between the matrix and the adjacent conduit at the micro-scale discovered in this study, although focused on the micro-scale, provide theoretical support and feasible ideas for water exchange research at the macro-scale. Especially by considering the heterogeneity of the matrix at the micro-scale, a more precise framework is provided for modeling karst aquifer dynamics. For instance, micro-scale pore structure features, such as connectivity and permeability, can be parameterized and further applied in regional-scale water exchange studies. As the spatial scale increases, the effects of heterogeneity become more complex. Therefore, future research should explore how these micro-scale mechanisms scale up in large systems, such as the application of methods like scaling laws or fractal models. By considering the multi-scale characteristics of karst systems through these methods, we can bridge the gap between micro-scale processes and large-scale hydrological behavior. In practical engineering applications, water exchange between the matrix and the conduit is widely present in areas such as groundwater reservoirs, infiltration dams, and soil remediation. Comprehensive integration of micro-scale influencing mechanisms with macro-scale hydrological behaviors can provide great predictions for the migration of pollutants and water resource management in karst aquifers.

Conclusion

This study developed a numerical model to explore the water exchange between the matrix and the adjacent conduit in karst water-bearing media at the micro-scale by the Stokes-Brinkman equation and the digital core technology. Across a range of simulation scenarios, the micro-scale characteristics and influence mechanism of water exchange were revealed, which provide a scientific basis for understanding the migration mechanism of the karst water system. The main conclusions are as follows :

-

The significant variations in permeability and porosity across different matrix samples are key determinants of their distinct hydraulic properties. These differences critically influence the water exchange process between the matrix and the adjacent conduit. This highlights the necessity of incorporating matrix hydraulic properties into analyses of groundwater flow and solute transport dynamics in karst systems.

-

The characteristics of the water exchange interface between the matrix and the adjacent conduit presented local differences in flow velocity and gradient pressure changes, which revealed the non-uniformity and dynamic balance of water exchange, offering a new perspective for the flow characteristics and supporting the utilization of karst water resources and predictions of pollutant migration.

-

There was a clear linear positive correlation between the water exchange efficiency and the flow velocity of the conduit inlet, this could be explained by the hydraulic head difference between the matrix and the adjacent conduit, which further confirms the key motivating effect of hydrodynamic factors on water exchange.

-

The microscopic heterogeneous structure of the matrix has a notable influence on the interface flow velocity and water exchange efficiency, suggesting that future research should account for the effect of the heterogeneity of karst aquifers on water flow dynamics to improve the accuracy and reliability of simulation.

Data availability

All relevant data are included in the manuscript.

References

Jourde, H. & Wang, X. Advances, challenges and perspective in modelling the functioning of karst systems: a review. Environ. Earth Sci. 82, 3961–39626 (2023).

Shoemaker, W. B., Cunningham, K. J., Kuniansky, E. L. & Dixon, J. Effects of turbulence on hydraulic heads and parameter sensitivities in preferential groundwater flow layers. Water Resour. Res. 44, W03501 (2008).

Bauer, S., Liedl, R. & Sauter, M. Modeling of karst aquifer genesis: Influence of exchange flow. Water Resour. Res. 39, 371–375 (2003).

Binet, S. et al. Water exchange, mixing and transient storage between a saturated karstic conduit and the surrounding aquifer: Groundwater flow modeling and inputs from stable water isotopes. J. Hydrol. (Amst) 544, 278–289 (2017).

Wang, Z., Guo, J., Qiao, L., Liu, J. & Li, W. Matrix–fracture flow transfer in fractured porous media: Experiments and simulations. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 55, 2407–2423 (2022).

Sivelle, V., Labat, D., Mazzilli, N., Massei, N. & Jourde, H. Dynamics of the flow exchanges between matrix and conduits in karstified watersheds at multiple temporal scales. Water (Basel) 11, 569 (2019).

Zhao, L. J. et al. Applying a modified conduit flow process to understand conduit-matrix exchange of a karst aquifer. CHINA Geol. 5, 26–33 (2022).

Shu, L. et al. Laboratory and numerical simulations of spatio-temporal variability of water exchange between the fissures and conduits in a karstic aquifer. J. Hydrol. (Amst) 590, 125219 (2020).

Cao, Y., Gunzburger, M., Hua, F. & Wang, X. Coupled Stokes-Darcy model with Beavers-Joseph interface boundary condition. Commun. Math. Sci. 8, 1–25 (2010).

Zhang, S. et al. Research on flow field characteristics in the karst tunnel face drilling hole (conduit) under the coupling between turbulence and seepage. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 143, 105455 (2024).

Lv et al. Quantitative 3D Spatial characterization and flow simulation of coal macropores based on mu CT technology. Fuel 200, 199–207 (2017).

Zhou, Q. et al. Evaluating the pore structure of low permeability glutenite reservoir by 3D digital core technology. SN Appl. Sci. 4, 294 (2022).

Kling, T. et al. Simulating stress-dependent fluid flow in a fractured core sample using real-time X-ray CT data. Solid Earth 7, 1109–1124 (2016).

Peng, X. L., Du, Z. M., Liang, B. S. & Qi, Z. L. Darcy-Stokes streamline simulation for the Tahe-Fractured reservoir with cavities. SPE J. 14, 543–552 (2009).

Arbogast, T. & Gomez, M. S. M. A discretization and multigrid solver for a Darcy-Stokes system of three dimensional Vuggy porous media. Comput. Geosci. 13, 331–348 (2009).

Jamal, M. S. et al. Assessment of unsteady Brinkman’s model for flow in karst aquifers. Arab. J. Geosci. 12, 12 (2019).

Bhattacharyya, A. Effect of momentum transfer condition at the interface of a model of creeping flow past a spherical permeable aggregate. Eur. J. Mechanics-B/Fluids. 29, 285–294 (2010).

Murad, M. A., Lopes, T. V., Pereira, P. A., Bezerra, F. H. R. & Rocha, A. C. A three-scale index for flow in karst conduits in carbonate rocks. Adv. Water Resour. 141, 103613 (2020).

Rezaei, F., Izadi, H., Memarian, H. & Baniassadi, M. The effectiveness of different thresholding techniques in segmenting micro CT images of porous carbonates to estimate porosity. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 177, 518–527 (2019).

Liu, J. S. et al. Quantitative prediction of the drilling azimuth of horizontal wells in fractured tight sandstone based on reservoir geomechanics in the Ordos basin, central China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 136, 105439 (2022).

Zhang, S., Liu, X. H., Liu, X. L. & Wang, K. The friction factor of the fracture-matrix system considering the effects of free flow, seepage flow, and roughness. J. Hydrol. (Amst) 628, 130602 (2024).

Muhsun, S. S., Saleh, M. S. & Qassim, A. R. Physical and CFD simulated models to analyze the contaminant transport through porous media under hydraulic structures. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 24, 3674–3691 (2020).

Fan, N. et al. Quantitative characterization of coal microstructure and visualization seepage of macropores using CT-based 3D reconstruction. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 81, 103384 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Promoting sustainable coal gas development: Microscopic seepage mechanism of natural fractured coal based on 3D-CT reconstruction. Sustainability 16, 4434 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 4227070098).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Writing an original draft, Data curation. D.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. G.A.: Software, Formal analysis, Writing review & editing, Project administration. T.H.: Formal analysis, Writing review & editing, Project administration.Y.C.: Writing review & editing, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Yang, D., An, G. et al. Numerical simulation of water exchange between the karst matrix and the adjacent conduit at the micro-scale. Sci Rep 15, 7844 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92288-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92288-y