Abstract

The intricate nature and varied forms of bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) highlight the need for new indicators to define tumor prognosis. Disulfidptosis, a novel form of cell death, is closely linked to BLCA progression, prognosis, and treatment outcomes. Our current goal is to develop a novel disulfidptosis-related immune prognostic model to enhance BLCA treatment strategies. Utilizing RNA-seq data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) , which included 419 patients (19 normal, 400 tumor), we performed weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to identify disulfidptosis-associated immune genes. Through multivariate Cox regression, and the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regularization, we established a disulfidptosis-related immune risk scoring system. A nomogram combining risk score and clinical features predicted prognosis. Model performance was validated through survival curve analysis and independent validation cohort. Immune checkpoints, cell infiltration, and tumor mutation load were assessed. Differential gene enrichment analysis was conducted. Prognostic genes were validated via in vitro experiments. Eight immune genes related to disulfidptosis were identified and verified in BLCA prognosis. A prognostic model outperformed previous ones in predicting overall survival (OS) for high- and low-risk groups. Patients with low-risk scores had higher OS rates and tumor mutation burden (TMB) compared to high-risk score patients. CD4 memory T cells, CD8 T cells, M1 macrophages, and resting NK cells were found to be higher in the low-risk group. Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment may be more effective for the low-risk score group. High-risk score group exhibited stronger correlation with cancer malignant pathways. Knocking out tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 12 A (TNFRSF12A) inhibits BLCA cell proliferation and invasion while overexpressing it has the opposite effect. We constructed a novel risk score model that combines disulfidptosis and immune genes, demonstrating good prognostic prediction performance. We discovered and verified that the TNFRSF12A gene is an oncogene in BLCA, which may help provide personalized guidance for individualized treatment and immunotherapy selection for BLCA patients to a certain extent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) is a highly aggressive malignant tumor with poor prognosis. BLCA accounts for about 570,000 new cases and 210,000 deaths worldwide1. According to the depth of tumor invasion into the bladder wall, BLCA can be divided into two subtypes: (a) non-muscle-invasive BLCA (NMIBC), confined to the urothelium and lamina propria; and (b) muscle-invasive BLCA (MIBC) involving muscle invasion (T2 stage) or higher. NMIBC accounts for about 70% of organ-confined BLCA2. Over the past five years, approximately 90% of NMIBC patients have survived, but approximately 15–20% will progress to MIBC3. MIBC accounts for the remaining 30% of organ-limited BLCA and has a higher propensity to spread to lymph nodes and other organs, with a 5-year OS rate of approximately 60-70%. Therefore, careful risk stratification of BLCA is needed to enhance clinical decision-making and counseling of patients.

In BLCA, immune cells, cytokines, and rich immune gene expression patterns form a unique tumor microenvironment, making it a good candidate for immunotherapy4. In fact, BLCA was one of the first cancers to be treated with immunotherapy using Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), which has been used to treat BLCA for nearly 50 years5. It is a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) that activates Toll-like receptors, produces inflammatory cytokines, TNF, and GM-CSF, thereby activating neutrophils and monocytes6. Secondly, the BCG stimulates CD4+ T cells to activate adaptive immune responses dominated by Th1 cells6,7. Despite BCG’s effectiveness, progression and relapse rates vary from 5 to 50%, depending on individual risk stratification, along with side effects8. It is estimated that 30–40% of patients with intermediate- or high-risk NMIBC fail the BCG treatment for a variety of reasons despite initial success with BCG9. CTLA4, PD-1, and PD-L1 have been identified as key immune checkpoint proteins, making cancer immunotherapy through immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) an effective treatment for BLCA. In contrast, only 25% of metastatic/advanced BLCA patients respond to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 ICB10. Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore the immunological characteristics of high-risk groups with BLCA, obtain key indicators for judging prognosis, and find new potential therapeutic targets.

Disulfidptosis is a new type of cell death triggered by disulfide stress resulting from cystine overaccumulation. In contrast to ferroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis, it is a new form of regulated cell death. It is different from autophagy. Glucose starvation triggers disulfidptosis in cells when the Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 (SLC7A11) gene is expressed at high levels11. This finding demonstrates the metabolic vulnerability of cancer cells with high SLC7A11 expression, providing a potential therapeutic avenue for the treatment of tumors by targeting their dependence on glucose and Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) for survival. Now, multiple studies have established a strong link between disulfidptosis and cancer. Liu et al.’s study demonstrated that inhibition of glucose transporters leads to robust cell death in cancer cells with high expression of SLC7A11, a process that may be mediated by the disulfidptosis mechanism11. According to Qi et al., gene expression levels related to disulfidptosis may correlate with lung adenocarcinoma progression using extensive RNA-seq data12. Similarly, multiple prognostic models have been established in colon cancer13, glioma14, melanoma15 and breast cancer16 to predict cancer prognosis and survival rates. However, the relationship between BLCA and disulfide mortality remains unknown.

This study aimed to identify a disulfidptosis and immune gene signature to predict prognosis in BLCA. An eight-gene signature based on disulfidptosis-related immune genes was identified and validated from extensive BLCA transcript data. Through this feature, BLCA’s molecular mechanism will be better understood and guidance for personalized immunotherapy will be provided.

Materials and methods

Data collection and sample information

The flow chart of our study is illustrated in Fig. 1. RNA-seq data sets of 400 BLCA specimens and 19 normal specimens were obtained from the TCGA database. Corresponding clinical characteristics data of the patients were downloaded. These raw data were normalized at the fragment expression level per million bases, and transcripts per million (TPM) values were transformed using log2(TPM + 1) transformation. The TCGA-BLCA samples were randomly divided into training and internal test groups in a 1:1 ratio using R software. The external test group (ID: GSE32894) and single-cell sequencing data (ID: GSE130001) retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Those samples with duplicate characteristics or incomplete survival data were excluded.

Establishing a risk score to predict overall survival in BLCA in the training cohort

In the training cohort, genes associated with OS were identified using Univariate Cox regression analysis filtered at p < 0.05. The LASSO algorithm mitigated multicollinearity among genes related to prognosis, and for prognosis-related genes, the penalty parameters were optimized through 10-fold cross-validation using the R package “glmnet”. Multivariable Cox regression was conducted on genes with non-zero regression coefficients derived from LASSO regression analysis. The risk score was constructed by multiplying the expression level of each gene by its corresponding regression coefficient derived from multivariable Cox regression analysis for each gene17. Patients were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the optimal cutoff value of the risk score. R packages “survminer”, “survival ROC” and “timeROC” were used to generate Kaplan–Meier survival curves and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves (ROCs) to evaluate the performance of risk score in predicting survival.

Correlation and stratification analysis of risk scores

In order to determine whether the risk score can be used as a prognostic indicator, we performed a multivariate and univariate Cox regression analysis incorporating the risk score and clinical characteristics. Genetic mutations were analyzed using TCGA data on genetic changes.

Nomogram construction

We used the “Regplot” software package to create a line graph to predict OS based on clinical characteristics and risk scores. Each clinically significant feature was scored using a nomogram model, and all individual scores were summed to give a total score. Comparison of the AUCs of time-dependent ROC curves for one, three, and five-year survival rates was used to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the nomogram. The nomogram was tested for its predictive accuracy using calibration curves and concordance index (C-index).

Tumor immune related analysis

In order to examine the correlation between this model and immune infiltration status, seven algorithms were used (XCELL, TIMER, QUANTISEQ, MCPCOUNTER, EPIC, CIBERSORT-ABS, and CIBERSORT) to calculate the immune infiltration profile of the TCGA dataset. For analyzing differences in the content of immune infiltrating cells among different risk groups, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, limma, tidyverse, scales, ggplot2 and ggtext R software packages were used. With the estimation algorithm, we compared immune and stromal cell abundance among different groups and calculated StromalScore, ImmuneScore, and ESTIMATE scores (StromalScore + immune score). Furthermore, we examined the differential expression of immune checkpoint molecules in high- and low-risk groups using the Wilcoxon test to compare inhibitory or stimulatory checkpoint molecules. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Calculation of TMB

TMB was calculated from the change in total human exon length for each sample using a Perl script. The chromosomal location of the gene is denoted by R. The “ggpubr” package was used to examine potential differences between low- and high-risk groups in immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) responses18.

Differential gene expression analysis and functional enrichment analysis

Patient samples were assigned to high-risk and low-risk groups based on the optimal cutoff value of the risk score. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified when the |Log2FC| > 2 and FDR < 0.05. Using ‘‘clusterProfiler’’ package, we examined the difference among biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular function (MF) of the target gene list based on enriched biological activities and signaling pathways. In addition, the enriched pathways were identified by KEGG enrichment analysis. Differential expression genes were subjected to GO and KEGG enrichment analysis by using the Wallenius non-central hypergeometric distribution. A p-value and a q-value < 0.05 were taken as statistically significant.

Cell cultures

We used 3 cell lines, the human BLCA cell lines TCCSUP, 5637 and mouse RAW264.7, all from the American ATCC cell bank. The culture medium used Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) supplemented with 1% penicillin and streptomycin (P/S, Gibco). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The freezing conditions were liquid nitrogen. During the passage process, 0.25% trypsin (Gibco) was used for digestion and digestion was carried out in a 37 °C incubator for 1 min.

Cell transfection

Using RNAi technology, human BLCA cell lines TCCSUP and 5637 were transiently transfected with Lipofetamine3000 (Invitgen, USA), Opti-MEM (Life Technologies, USA) and other reagents. Cell RNA was extracted after culturing under optimal conditions, and RT-qPCR was used to determine how effectively genes were silenced or overexpression. The constructed cells were seeded in a 96-well plate, and the fluorescence value (OD value) of the two cells at 450 nm was detected at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h using the CCK-8 kit (Solaibao, Beijing, China) to compare the proliferation ability of the two cells. All experiments were conducted in triplicates, with a p value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Colony formation assay

TCCSUP and 5637 cells (1000 cells per well) were incubated in 6-well plates, and after culturing the cells for 2 weeks, the resulting colonies were fixed and stained with crystal violet. Images of cell colonies were taken using a digital camera and counted. All experiments have been performed in triplicate.

Transwell assay

The Liquid Matrigel matrix gel (Corning) was polymerized (37 °C, 1 h) after 1:9 dilutions in serum-free medium. Next, 70 µl of the diluted substrate gel was taken and spread in the Transwell chamber of a 24-well plate, and then it was placed in the incubator for 1 h to make the substrate gel solidified. The cells were resuspended in 200 μl of culture medium without fetal bovine serum and the cell volume was adjusted to 5 × 104 cells, and then they were placed in the upper chamber. 600 μl of complete culture medium was filled into the lower chamber and then it was placed in the cell culture incubator for 48 h. The chamber was taken out, the medium was aspirated, and it was washed twice with PBS. The cells in the Matrigel matrix gel and small chamber were wiped with a cotton swab, and 600 μl of polymethanol was added to the lower chamber for 30 min. The polymethanol was aspirated and 600 μl of crystal violet was added to the lower chamber for staining. It was stained for 30 min. After being washed twice with PBS, pictures were taken and the images were recorded under a microscope. The quantity of invasive cells is quantified by counting the cell numbers from three random fields at a magnification of ×100. All experiments have been performed in triplicate.

Cell co-culture

Transwell inserts (0.4-micron holes; Corning, New York, USA) for indirect cell co-culture. 5637 cells (5 × 103 cells/well) were inoculated in the upper compartment and RAW264.7 (5 × 104 cells/well) was placed at the bottom of the 24-well plate. RNA was extracted from RAW264.7 cells after co-culture for 24 h.

Western blotting analysis

Bladder cancer cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The lysed tissues and cells underwent further processing via ultrasonic disruption to facilitate the separation of supernatant from cell debris, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The protein concentration in the supernatant was measured using a BCA assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Subsequently, proteins were separated through electrophoresis on an SDS-PAGE gel, and the resulting bands were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Initially, the membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h. Then, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-TNFRSF12A (1:1000, Sigma, SAB1409412), anti-SLC7A11 (1:1000, CST, #98051) and anti-β-actin (1:1000). Following this, the membrane was incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, the bands were detected via chemiluminescence, and the relative density of protein immunoblot images was analyzed using ImageJ software. The raw blots were presented in the Supplementary Material 1.

Real-time q-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). CDNA was synthesized from total RNA using a reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Forty cycles were performed on the ABI PRISM 7500FAST PCR sequence detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with each cycle following the following PCR cycle mode: denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 20 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The relative changes in mRNA content were determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method. All quantitative RT-PCR reactions were carried out in three independent experiments. The following primer pairs were used:

PD-L1 (Human) F: 5′-TGGCATTTGCTGAACGCATTT-3′, R: 5′-TGCAGCCAGGTCTAATTGTTTT-3′.

GAPDH (Human) F: 5′-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3′, R: 5′-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3′.

Arg1 (Mouse) F: 5′-CTCCAAGCCAAAGTCCTTAGAG-3′, R: 5′-GGAGCTGTCATTAGGGACATCA-3′.

GAPDH (Mouse) F: 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′, R: 5′-GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA-3′.

In vivo tumor xenograft study

6-week-old male nude mice (weighing 19–21 g) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Wenzhou Medical University. The mice were divided into two groups, and each group was subcutaneously injected with 5 × 106 Vec 5637 cells and OE-TNFRSF12A 5637 cells on their backs. The mice were kept under suitable temperature and lighting conditions. Meanwhile, they were regularly fed with standard feed and water. After tumor inoculation, monitor tumor growth using a vernier caliper for 2 weeks. Two weeks later, the mice were humanely euthanized using isoflurane anesthesia, and tumor specimens were collected for tumor weight measurement. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula V = (length × width2)/2. All animal experiments and experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical University, and adhered to the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health as well as the ARRIVE Guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R v.4.2.2. A Student’s t-test was performed on continuous variables for comparison with independent variables. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were conducted for comparisons of categorical variables for comparison with non-normally distributed variables. An analysis of Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests was carried out, with a p value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Screening of DEGs, construction of WGCNA network, and identification of BLCA disulfidptosis-related immune genes

This study downloaded the BLCA dataset from TCGA, and identified a total of 4925 DEGs (containing sample data from 400 BLCA patients and 19 healthy individuals) based on |log2FC| > 2, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. With the WGCNA algorithm, a gene co-expression network was constructed. We constructed a dendrogram of gene hierarchies, resulting in the identification of six gene modules (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, based on the correlation between module feature values and the disulfidptosis phenotype of BLCA, we finally determined that the “Turquoise” module containing 6080 genes was the most valuable positively correlated module in BLCA (Cor = 0.2, p = 1 × 10−4) (Fig. 2B). In order to explore the role of disulfidptosis-related immune mechanisms in predicting the prognosis of BLCA, we first selected the module with the highest positive correlation with disulfidptosis (purple module), then crossed with DEGs and immune-related genes, and finally obtained 135 crossed genes (Fig. 2C).

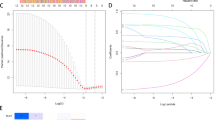

Identification of BLCA disulfidptosis-related immune genes. (A) Dendrogram of all differentially expressed genes clustered based on dissimilarity measure (1-TOM). The color ramp shows the results obtained from automated single block analysis. (B) Heatmap of correlations between module signature genes and clinical features of BLCA disulfidptosis. The values in the small cells in the figure represent the two calculated correlation values, the correlation coefficient between each feature value and each module, and the corresponding statistically significant p-value. The color corresponds to the magnitude of the correlation; the darker the red, the more positive the correlation; the darker the green, the greater the negative correlation. (C) Crossover of BLCA-related genes. (D) Screening of genes associated with disulfidptosis by univariate Cox regression, with red indicating high risk and green indicating low risk. (E) Use Lasso-cox regression analysis to determine the independent variable coefficients. (F) Calculate the optimal lambda value, as shown by the first black dashed line from the left on the logarithmic scale. TOM topological overlap matrix.

Construction and validation of the risk scoring model

Among the 135 crossed genes, a total of 22 genes with significant differences were found to be related to BLCA prognosis through univariate Cox regression analysis, including ACKR3, APOBEC3G, CCL19, CCL21, CXCL12, DHX58, LMBR1, LMMP9, NFATC1, NR3C1, PDGFD, PLXNB1, PPP3CC, PSMB8, PSME2, PTPN6, S100A6, S1PR2, SDC2, SRC, TAPBP, TNFRSF12A (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2D). Subsequently, the Lasso-Cox regression algorithm was applied to the selected feature genes in the TCGA training cohort to reduce overfitting of the 22 genes. Based on the optimal lambda value selected via cross-validation and corresponding coefficients in the Lasso-Cox regression analysis, 8 genes related to the prognosis of BLCA were obtained, namely, ACKR3, MMP9, PDGFD, PSMB8, PTPN6, SDC2, SRC and TNFRSF12A (Fig. 2E, F) and its corresponding coefficient. In order to predict the prognosis of BLCA patients, we calculated a risk score based on the expression values of eight genes and divided the TCGA training cohort into high-risk and low-risk groups. The risk score was calculated using the following equation:

Risk score = (ACKR3 × 0.28286) + (MMP9 × 0.15249) + (PDGFD × 0.25586) − (PSMB8 × 0.35380) − (PTPN6 × 0.34240) − (SDC2 × 0.20622) − (SRC × 0.28076) + (TNFRSF12A × 0.15415).

The risk map shows the distribution of risk scores and their relationship with survival outcomes (Fig. 3A, B), and the heat map shows the expression levels of risk genes in the high-risk and low-risk groups (Fig. 3C). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the survival time of patients in the high-risk group was shorter than that of the low-risk group in the training set and test set 1, 2, and 3 (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3D–G). These results indicate that the risk score based on disulfidptosis-related immune genes has good predictive performance in BLCA patients. For the TCGA training cohort, 10-year time-dependent C-index analysis showed that risk score had good prognostic accuracy in predicting clinical outcomes compared with risk score, age, sex, and TNM in BLCA patients (Fig. 3H). As shown by the area under the risk model curve, the AUCs for predicting BLCA patients’ survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years based on their risk scores were 0.748, 0.777, and 0.777, respectively (Fig. 3I–K). Compared with other clinicopathological characteristics, the model demonstrated excellent predictive ability (Fig. 3I–K).

Identification of prognostic markers for the disulfidptosis-related immune gene risk model by performing Lasso Cox regression analysis on the TCGA training cohort. (A,B) Distribution of risk scores (RS) and survival status of predicted signatures based on the disulfidptosis-related immune gene risk model. (C) Heat map depicting the gene expression profile of the disulfidptosis-associated immune gene risk model in high-risk score and low-risk score groups according to prognostic characteristics. (D–G) In the training set and test set, the Kaplan-Meier survival curve of the generation probability of patients in the low and high-risk score groups, the prognosis of the patients in the high risk-score group is significantly lower than that of the low-risk score group, the difference is statistically significant (P < 0.0001). (H) C-index curve for risk score, age, sex, T, and AJCC stage. (I–K) ROC curves comparing risk scores and clinical factor-related risk models at 1, 3, and 5 years.

Figure 4 shows the OS curve, which is based on the Kaplan-Meier method and the LOG-RANK test, taking into account the following clinical parameters: age, sex, T stage, N stage, M stage, and AJCC stage. We observed that BLCA can be determined according to age (≤ 65, n = 159; > 65, n = 241), gender (male, n = 296; female, n = 104), T (grade 3–4, n = 247), N (grade 0, n = 233; grade 1–3, n = 125), M (M0, n = 194) and AJCC stage (stage III–IV, n = 269 cases) to predict the survival of different clinical subgroups (p < 0.001). The results showed that high-risk score values were associated with poorer prognosis in BLCA patients (Fig. 4). As a result of these results, it appears that this model can be used to predict the prognosis of BLCA patients based on various clinical and pathological characteristics.

Comparison of the prognostic forecasting model with other published models

To evaluate the performance of the signatures relative to existing signatures, we included Cao (Fig. 5A), Chen (Fig. 5B), Liu (Fig. 5C), Luo (Fig. 5D), Wang (Fig. 5E), Zhu (Fig. 5F), six published OS risk prediction models for BLCA patients. Based on the ROCs of each signature, it is evident that all models perform well in making predictions, and the AUCs of 1-year, 3-year and 5-year OS in our model were 0.748, 0.767, 0.775 respectively, which is higher than the AUCs of the 6 previously published signatures. In addition, the C-index of our model is 0.702 higher than other models (Fig. 5G), while the C-index of the other 6 signatures were 0.655, 0.671, 0.564, 0.654, 0.656, and 0.63 respectively.

Analyzing independent prognostic factors and developing nomograms

To screen independent prognostic factors, univariate and multivariate Cox analyzes were performed on clinical characteristics and risk scores. Univariate and multivariate Cox analysis (Fig. 6A, B) showed that risk score was an independent risk factor for patients with BLCA. Then, based on age, T and risk score, we constructed a nomogram model, quantified the scores for each variable, and estimated the survival probability using a calculation formula and a total score formula (Fig. 6C). The calibration curve analysis and DCA were then used to verify the model’s accuracy, stability, and clinical usefulness. Calibration curve results show that 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS were consistent with predicted values (Fig. 6D), indicating the good performance of the prognostic nomogram. A clinical decision curve analysis (DCA) revealed that the model constructed by combining five variables had a higher clinical benefit rate than any of the variables alone (Fig. 6E). The above results indicate that our prediction model can accurately and robustly predict prognoses.

Independent prognostic ability of selected signature genes. (A,B) An analysis of the relationship between OS risk score and different clinical parameters using univariate and multivariate Cox regression. (C) Nomogram including risk index and clinical parameters predicting prognosis of BLCA. (D) Calibration curve of the nomogram showing agreement between predicted and observed 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates. (E) Decision curve analysis (DCA) of the nomogram in comparison with other parameters.

Analysis of tumor microenvironment and immune cell infiltration

In tumor formation and prognosis, immune cells play a crucial role. To understand the immune cell infiltration of BLCA patients in the TCGA cohort, we evaluated the correlation between risk scores and immune cell infiltration levels using XCELL, TIMER, QUANTISEQ, MCPCOUNTER, EPIC, CIBERSORT-ABS, and CIBERSORT analyses. The results showed that there were significant differences in immune cell types in tumor tissues of BLCA patients (Fig. 7A). The risk score was positively correlated with Cancer-associated fibroblast, Stroma score, M0 Macrophage, Hematopoietic stem cell, Endothelial cell, and negatively correlated with CD8+ T cell, CD4+ T cell, Follicular helper T cell, and CD8+ naïve T cells. Both prognostic genes and risk scores were significantly associated with infiltrating immune cells, according to Pearson correlations (Fig. 7B). Next, we analyzed the correlation between infiltrating immune cells and eight signature genes and risk scores. The results showed that M0 macrophages, memory resting CD4 T cells, Neutrophils, naive B cells, and active Mast cells were positively correlated with risk scores, while CD8 T cells, active CD4 memory T cells, T follicular helper cells, resting NK cells, γ-Delta T cells, and active Dendritic cells were negatively correlated with the risk score (Fig. 7C). The number of immune cells was also examined by our study in relation to eight genes (Fig. 7C). According to our research, these 8 genes affect most immune cells. A low-risk group had a greater number of activated CD4 memory T cells (Fig. 7D), activated CD8 memory T cells (Fig. 7E), M1 macrophages (Fig. 7F), and resting NK cells (Fig. 7G). Figure 7H shows the proportion of high-risk and low-risk patients in various immune subtypes, indicating that the proportion of low-risk patients is greater than that of high-risk patients. These results indirectly suggest different immune landscapes in the two risk groups.

Differences in the tumor immune microenvironment between the low-risk score group and the high-risk score group. (A) Bubble plot of correlation between risk score and immune cell infiltration. (B) Correlation of immune cells with risk scores and 8 genes in BLCA patients. (C) Correlation of 21 immune cell types with eight disulfidptosis-related immune genes in the established model. Ordinate represents immune cells, while abscissa represents genes related to disulfidptosis. Red indicates a positive correlation and blue indicates a negative correlation. Comparison of activated CD4 memory T cells (D), CD8 T cells (E), M1 macrophages (F), and resting NK cells (G) between the two risk groups. (H) Immunotherapy cohort analysis of low-risk and high-risk groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Immune checkpoint blockade therapy has been approved for the treatment of BLCA with great success. To explore the correlation between disulfidptosis and BLCA immunotherapy, immunotherapy-related parameter, tumor mutation burden (TMB), and immunological checkpoints were studied in this study. First, we investigated the relationship between 8 signature genes and risk scores as well as common immune checkpoints (ADORA2A, BTLA, CD160, CD244, CD274, CD96, CSF1R, CTLA4, HAVCR2, IDO1, IL10, IL10RB, KDR, KIR2DL1, KIR2DL3, LAG3, LGALS9, NECTIN2, PDCD1, PDCD1LG2, TGFB1, TGFBR1, TIGIT and VTCN1) (Fig. 8A). The risk score was positively correlated with CSF1R, HAVCR2, IL10, KDR, PDCD1LG2, TGFB1, and TGFBR1 genes, and negatively correlated with CD160, CD96, IL10RB, and LGALS9. The expression levels of the eight signature genes were associated with most immune checkpoints. Using TMB correlation analysis, risk score was found to be negatively correlated with TMB (R = − 0.12, p = 0.022, Fig. 8B). Furthermore, TMB was higher in the low-score group compared with the high-score group (p = 0.0067; Fig. 8C). We evaluated IPS immunotherapy response. According to the IPS (CTLA4-/PD-1−, CTLA4+/PD-1−, CTLA4-/PD-1+ and CTLA4+/PD-1+), patients in the low-risk group showed significant therapeutic benefit from ICIs treatment (Fig. 8D–G). Furthermore, analysis of the immunotherapy cohort found that risk scores were lower in the responder group (Fig. 8H). These results suggest that risk scores play an important role in predicting immunotherapy response and that lower risk scores may result in better immunotherapy responses.

(A) Relationship between the expression and risk scores of 8 characteristic genes and common immune checkpoints in BLCA tissues. (B) Correlation between risk score and TMB score in the TCGA dataset. (C) The TMB of the high-risk score group is lower than that of the low-risk score group. (D–G) Correlation between risk and four IPS scores associated with a single ICI (anti-CTLA4 or anti-PD1) or their combination. (H) Boxplot showing that CR/PR patients have significantly higher risk scores than SD/PD patients have a lower risk score. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The biological pathways analyses

An analysis of GO and KEGG enrichment between the two groups identified DEGs. In the GO analysis, biological processes were mostly associated with “the extracellular matrix organization”, “extracellular structure organization”, “external encapsulating”, “structure organization ossification” and “connective tissue development (Fig. 9A, B). Enrichment in the cellular component category was associated with “collagen-containing extracellular matrix”, “endoplasmic reticulum lumen”, “collagen trimer” and “basement membrane”. KEGG analysis showed that the DEGs were mostly enriched in pathways related to “PI3K-Akt signaling pathway”, “Focal adhesion”, “Human papillomavirus infection”, “Protein digestion and absorption” and “ECM-receptor interaction” (Fig. 9C, D). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that the risk score was positively correlated with WNT, TGF-BETA, MAPK, HEDGEHOG, CALCIUM and other pathways, and negatively correlated with the RIG-I like receptor pathway. Eight disulfidptosis-relative genes were associated with multiple tumor pathways (Fig. 9E).

Functional analysis of DEGs for people with high insurance scores and low insurance scores based on the TCGA data set. (A) GO analysis demonstrates the richness of molecular BP, CC, and MF. (B) GO function annotation circle plot. (C) KEGG pathway analysis50 showing significantly enriched pathways. (D) KEGG pathway function annotated circular plot. (E) KEGG pathway analysis shows that risk scores are associated with multiple tumor-related signaling pathways. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

TNFRSF12A promotes BLCA cell proliferation and invasion

The above data indicate that the disulfidptosis-related immune gene has an impact on the prognosis of BLCA patients. Therefore, we explored whether the above genes could influence tumor progression at the cellular level. We found that TNFRSF12A was the highest expressed in tumor cells through single-cell data set (GSE130001) analysis (Fig. 10A), so we selected this gene to further explore its function. siRNA was used to knock out the TNFRSF12A gene in the TCCSUP cell line, and plasmid was used to overexpress the TNFRSF12A gene in the 5637-cell line. The results of CCK-8 (Fig. 10B) and colony formation experiments (Fig. 10C) showed that knocking out the TNFRSF12A gene reduced the proliferation activity of TCCSUP cells, and overexpressing the TNFRSF12A gene promoted the proliferation activity of 5637 cells. Transwell results showed that knocking out the TNFRSF12A gene reduced the invasive activity of TCCSUP cells, and the number of cells overexpressing TNFRSF12A that penetrated the chamber membrane was significantly increased (Fig. 10D). TNFRSF12A affects the invasive ability of BLCA at the cellular level. Blocking the TNFRSF12A gene may have potential implications for tumor treatment. Western blotting results showed that after transfection with plasmids overexpressing TNFRSF12A, TNFRSF12A protein expression was upregulated and SLC7A11 protein expression was decreased in 5637 cells (Fig. 11A). On the contrary, after transfection with TNFRSF12A siRNA, TNFRSF12A protein expression was downregulated and SLC7A11 protein expression was upregulated in 5637 cells (Fig. 11B). Tumor photos showed that overexpression of TNFRSF12A significantly promoted subcutaneous tumor growth in 5637 cells, and the subcutaneous tumor volume in the OE group was significantly larger than that in the control group (Fig. 11C). Consistent with the observations on tumor volume, the tumor weight in the knockdown group also significantly decreased (Fig. 11D).

Effects of TNFRSF12A gene on proliferation, migration and invasion of bladder cancer cells. (A) Single cell data set (GSE130001) analysis found that 8 disulfidptosis-related immune genes were expressed in tumor endothelium, epithelium, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts. (B) Effects of knocking down and overexpressing TNFRSF12A on the viability of TCCSUP and 5637 cells. (C) Effects of knocking out and overexpressing TNFRSF12A on the colony formation ability of TCCSUP and 5637 cells. (D) Transwell analysis of the effect of TNFRSF12A on the invasion ability of TCCSUP and 5637 cells. n = 3. * and **, represent p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively. All quantitative values were obtained using the mean ± SD.

Effects of TNFRSF12A gene on cell derived xenograft and immunity of bladder cancer cells. (A) Western blot analysis showed the effect of overexpression plasmid on TNFRSF12A and SLC7A11 protein expression in 5637 cells. (B) Western blot analysis showed the effect of SiRNA on TNFRSF12A and SLC7A11 protein expression in 5637 cells. (C) The effect of TNFRSF12A on the tumorigenesis of nude mice was measured in a xenograft trial. (D) The tumor size and weight of nude mice were measured. (E) Downregulation of TNFRSF12A gene suppresses PD-L1 expression in 5637 cells. (F) Downregulation of TNFRSF12A gene inhibits M2 polarization in RAW264.7 cells. n = 3. *, ** and ***, represent p < 0.05, p < 0.01and p < 0.001, respectively. All quantitative values were obtained using the mean ± SD.

Changes of PD-L1 and macrophage polarization after transfection with SiRNA

PD-L1 protein is a transmembrane protein mainly expressed on some tumor cells and immune cells. It inhibits T cell activation by binding to programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1), thereby reducing the immune system’s attack on tumor cells19. Therefore, we used PCR to detect the expression level of PD-L1 after siRNA transfection. The results indicate that the decrease in TNFRSF12A expression level is accompanied by the expression level of PD-L1 (Fig. 11E). To investigate the effect of TNFRSF12A on polarization of tumor associated macrophages, we co cultured 5637 cells with RAW264.7 cells and detected macrophage polarization. The results showed that inhibiting the TNFRSF12A gene weakened the expression of ARG-1 gene (Fig. 11F). The ability of tumor cells to induce M2 polarization in macrophages is weakened.

Discussion

BLCA is among the top ten most common cancers in the world20. Currently, treatment options for BLCA have expanded from traditional chemotherapy to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Among them, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 have achieved encouraging results. Unfortunately, the clinical benefit of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy was not significantly improved compared with standard first-line platinum-based chemotherapy21,22. Therefore, identifying biomarkers is critical with high prognostic values in order to better characterize the immune component of nodal BLCA, which is vital for patient stratification, immunotherapy, and prognosis. Recently, disulfidptosis has been identified as a novel mode of programmed cell death11. Previous studies have initially explored the role of disulfidptosis genes in BLCA, and several clinical indicators of disulfidptosis genes have been developed for prognostic assessment of BLCA23,24. In spite of similar clinical characteristics, patients’ molecular profiles are very heterogeneous, leading to significant clinical outcomes. Tumor immunity is closely related to tumor occurrence, development, treatment response, and drug resistance25. More and more immune genes are used in the treatment and prognosis classification of BLCA26,27. A combined predictor of disulfidptosis and immunity is undoubtedly more effective in predicting prognosis. To assist in identifying BLCA patients’ OS prognoses, we identified eight disulfidptosis-related immune genes and developed a nomogram model which includes clinical characteristics to determine BLCA patients’ individual treatment strategies. The validity of the signature was verified using an external verification dataset. In addition, an overexpressed gene TNFRSF12A was also discovered and its relationship with the malignant phenotype of BLCA cell lines was verified. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of combining disulfidptosis-related immune prognostic markers on the prognosis of BLCA.

In recent years, bioinformatics methods integrating multiple omics data have been widely utilized in tumor typing research28. For instance, GUI et al. successfully identified key driver genes of cervical cancer through LASSO Cox regression and integrated bioinformatics analyses17. Ye et al. successfully developed the CAFs-related index (CAFRI) based on comprehensive analysis of single-cell and batch RNA sequencing, and emphasized the value of CAFRI in predicting clinical outcomes, TIME, and response to ICIs in ovarian cancer patients18. Their statistical framework served as a methodological reference for the differential expression analysis in this study. In this study, we first developed a risk assessment model containing eight disulfidptosis-related immune genes (ACKR3, MMP9, PDGFD, PSMB8, PTPN6, SDC2, SRC, and TNFRSF12A) using Cox regression and Lasso regression. Based on the median risk score, patients were categorized as high-risk or low-risk. ACKR3 (atypical chemokine receptor 3, also known as CXCR7) is an atypical chemokine receptor with seven transmembrane regions. The protein plays a vital role in the proliferation and migration of tumor cells in a variety of tumor types. It regulates tumor angiogenesis or drug resistance, thereby promoting tumor progression and metastasis29. MMP9 has been confirmed to correlate with BLCA migration and invasion30. Platelet-derived growth factor-D (PDGF-D) has been shown to be associated with the migration, invasion and proliferation capabilities of rectal cancer31. In BLCA, the sequencing results of Wen et al. showed that the expression of PDGFD was significantly down-regulated in BLCA32. Jin et al. developed a prognostic prediction model including PDGFD33. In BLCA, PSMB8 was identified as a CD8 T cell-related gene that promotes CD8 T cell infiltration and was enriched during MHC class I tumor antigen presentation34. Multiple studies use PSMB8 to predict BLCA prognosis35,36. PTPN6 (protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor type 6) is a tyrosine phosphatase, and TCGA-based research shows that it may be a new prognostic biomarker for BLCA37. Syndecan-2 (SDC2) is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan whose altered expression is associated with poor prognosis in multiple cancers38,39. Aberrant activation of SRC signaling leads to enhanced BLCA migration and invasion capabilities40. The TNFRSF12A gene is associated with aging and hypoxia-induced inflammatory responses and plays a role in thyroid cancer progression41.

The 1, 3, and 5-year ROC curves demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in predicting the prognosis of BLCA. Survival analysis revealed distinct prognostic outcomes between low- and high-risk BLCA patients. Patients in the high-risk group have shorter survival times and higher mortality. Many BLCA prognostic models based on gene features have been developed, such as the 6 immune-related gene signal prognostic models constructed by Cao, Chen, Liu, Luo, Wang, Zhu et al. Compared with these models, our prognostic model has better prognostic accuracy for BLCA. Correlation analysis between risk score and clinicopathological characteristics shows that risk score is closely related to age, gender, T stage, N stage, tumor stage and poor prognosis. In order to improve the accuracy of prognosis prediction, we analyzed various factors (including double Sulfur mortality risk score, age, gender, TNM stage and pathological stage), a nomogram was developed and validated. Independent prognostic analysis results showed that age, gender, TNM stage and disulfidptosis risk score were significantly related to the prognosis of BLCA.

As an important part of immunotherapy, analysis of the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) helps predict the response to immunotherapy. In order to examine the significance of immune cell infiltration in BLCA risk groups, we analyzed lymphocyte proportions using XCELL, TIMER, QUANTISEQ, MCPCOUNTER, EPIC, CIBERSORT, and CIBERSORT-ABS. The results showed that immune infiltration and immune checkpoint results in low-risk groups showed a large number of highly infiltrated activated CD4 memory T cells (Fig. 7D), CD8 T cells (Fig. 7E), M1 macrophages (Fig. 7F), resting NK cells, these cells have strong-tumor immune function. Therefore, low-risk groups may be more responsive to immunotherapy. It is possible that our disulfidptosis-related immune score can indicate immune cell infiltration and the prognostic significance of different types of immune cells. Myoepithelial cells, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, endothelial cells, inflammatory cells, and bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) make up the stroma of tumors, which are widely believed to cooperate with cancer cells and other host cells to create a milieu that allows tumor growth, Microenvironment for progression, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis42. Through analysis of 8 disulfidptosis genes in the single cell data set (GSE130001), we found that TNFRSF12A has the highest expression level in tumor cells. We further explored the function of this gene through in vitro experiments. Knocking down the TNFRSF12A gene reduced the proliferation and invasion abilities of BLCA cells, while overexpressing the TNFRSF12A gene had the opposite effect. Nude mouse tumorigenesis experiment showed that overexpression of TNFRSF12A gene could accelerate the growth of bladder cancer tumor cells in vivo. SLC7A11 is a key subunit of the cysteine/glutamate reverse transporter, primarily responsible for transporting extracellular cysteine into the cell. Cysteine is reduced to cysteine within the cell, which then participates in the synthesis of glutathione (GSH). Elevated SLC7A11 expression increases intracellular GSH synthesis and enhances cellular antioxidant capacity, thereby inhibiting lipid peroxidation—a hallmark of disulfidptosis. Our results indicate that knocking down TNFRSF12A increases SLC7A11 expression, and cells may alleviate oxidative damage and reduce the occurrence of disulfidptosis by upregulating SLC7A11.The M2 polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) plays a crucial role in regulating tumor growth, migration, and angiogenesis43. Tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) signaling has been found to be a negative regulator of M2 polarization in TAMs44. Our research shows that inhibiting the TNFRSF12A gene can reduce M2 polarization in macrophages, consistent with previous studies. Simultaneously, inhibiting the TNFRSF12A gene downregulated the expression of PD-L1 in 5637 cells. This suggests that TNFRSF12A may become a target for immunotherapy in BLCA patients.

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) is an indicator of the average number of mutations in tumor cell DNA compared to healthy cells and serves as a predictive biomarker of general immunogenicity and tumor propensity to respond to ICIs45. In our study, a higher TMB level was observed in the low-risk group. This suggests that a higher tumor mutation load may indicate better efficacy of tumor immunotherapy.

In our study, DEGs related to high and low risk groups were analyzed using KEGG. The results revealed several major enriched pathways, including “PI3K-Akt signaling pathway”, “Focal adhesion”, “Human papillomavirus infection”, “Protein digestion and absorption” and “ECM-receptor interaction”. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (AKT) pathway has been shown to regulate multiple cellular functions, including proliferation, metabolism, and transcription46,47. Studies by López-Knowles, E et al. demonstrate that mutations in PIK3CA are common in BLCA, supporting the development of papillary and muscle-invasive tumors through different molecular pathways48. The research results of Dickstein et al. show that the AKT inhibitor AZ7328 inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in vitro and exerts a cytostatic effect on BLCA49. These studies revealed the key role of PI3K/Akt and other signaling pathways in the BLCA process, suggesting that disulfidptosis may regulate the occurrence and development of BLCA through the PI3K/Akt pathway. To determine the role of PI3K/Akt in disulfide ptosis, further studies are needed.

Finally, the 8 disulfidptosis genes we discovered were verified through in vitro experiments. The role of TNFRSF12A in bladder cancer is still unclear. Our study showed that silencing of TNFRSF12A gene significantly inhibited BLCA cell proliferation and invasion, while overexpression of TNFRSF12A gene did the opposite. This indicates that TNFRSF12A plays an important role in the malignant phenotype of BLCA and may be a potential BLCA tumor marker and a new target for tumor treatment.

This study has several limitations and shortcomings. First, our study is entirely based on the TCGA data set, and the predictive ability of the study results needs to be confirmed by independent prospective clinical studies. Second, genes other than TNFRSF12A have not been validated in vitro or in vivo, and it is possible to gain new insights into immunotherapy for BLCA by understanding these disulfidptosis-related immune genes more in-depth.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a new prognostic assessment model involving eight disulfidptosis-related immune genes, which can accurately predict the prognosis, TMB, and immunotherapy response in BLCA. This model provides new insights for developing targeted therapies for BLCA patients. TNFRSF12A acts as an oncogene by promoting BLCA cell proliferation and invasion, thereby driving tumor initiation and progression.

Data availability

The gene expression datasets (GSE32894, GSE130001) are publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The TCGA-BLCA gene matrix presented in the study could be obtained from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

References

Jubber, I. et al. Epidemiology of bladder cancer in 2023: a systematic review of risk factors. Eur. Urol. 84, 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.03.029 (2023).

Dyrskjøt, L. et al. Bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 9, 58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-023-00468-9 (2023).

Ritch, C. R. et al. Use and validation of the AUA/SUO risk grouping for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer in a contemporary cohort. J. Urol. 203, 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1097/ju.0000000000000593 (2020).

Nair, S. S., Weil, R., Dovey, Z., Davis, A. & Tewari, A. K. The tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy in prostate and bladder cancer. Urol. Clin. North Am. 47, e17–e54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2020.10.005 (2020).

Gandhi, N. M., Morales, A. & Lamm, D. L. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy for genitourinary cancer. BJU Int. 112, 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11754.x (2013).

Han, J., Gu, X., Li, Y. & Wu, Q. Mechanisms of BCG in the treatment of bladder cancer-current Understanding and the prospect. Biomed. Pharmacother. 129, 110393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110393 (2020).

Crispen, P. L. & Kusmartsev, S. Mechanisms of immune evasion in bladder cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 69, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-019-02443-4 (2020).

Ward Grados, D. F., Ahmadi, H., Griffith, T. S. & Warlick, C. A. Immunotherapy for bladder cancer: latest advances and ongoing clinical trials. Immunol. Investig. 51, 2226–2251. https://doi.org/10.1080/08820139.2022.2118606 (2022).

Pettenati, C. & Ingersoll, M. A. Mechanisms of BCG immunotherapy and its outlook for bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 15, 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-018-0055-4 (2018).

Gopalakrishnan, D., Koshkin, V. S., Ornstein, M. C., Papatsoris, A. & Grivas, P. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in urothelial cancer: recent updates and future outlook. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 14, 1019–1040. https://doi.org/10.2147/tcrm.S158753 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Actin cytoskeleton vulnerability to disulfide stress mediates Disulfidptosis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 25, 404–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-023-01091-2 (2023).

Qi, C., Ma, J., Sun, J., Wu, X. & Ding, J. The role of molecular subtypes and immune infiltration characteristics based on disulfidptosis-associated genes in lung adenocarcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 15, 5075–5095. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204782 (2023).

Chen, P., Yu, J., Luo, Q., Li, J. & Wang, W. Construction of disulfidptosis-related LncRNA signature for predicting the prognosis and immune escape in colon adenocarcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 23, 382. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-03020-x (2023).

Li, X. M. et al. Identification of disulfidptosis-related genes and immune infiltration in lower-grade glioma. Open. Med. (Wars) 18, 20230825. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2023-0825 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Leveraging a disulfidptosis-related signature to predict the prognosis and immunotherapy effectiveness of cutaneous melanoma based on machine learning. Mol. Med. 29, 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-023-00739-x (2023).

Liang, J. et al. Identification of disulfidptosis-related subtypes, characterization of tumor microenvironment infiltration, and development of a prognosis model in breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 14, 1198826. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1198826 (2023).

Gui, Z. et al. Construction of a novel cancer-associated fibroblast-related signature to predict clinical outcome and immune response in cervical cancer. Transl. Oncol. 46, 102001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2024.102001 (2024).

Ye, Y. et al. Identification of a cancer associated fibroblasts-related index to predict prognosis and immune landscape in ovarian cancer. Sci. Rep. 13, 21565. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48653-w (2023).

Zhou, Y. J. et al. PD-L1: expression regulation. Blood Sci. 5, 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/bs9.0000000000000149 (2023).

Powles, T. et al. Bladder cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 33, 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.11.012 (2022).

Powles, T. et al. Pembrolizumab alone or combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma (KEYNOTE-361): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 22, 931–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00152-2 (2021).

Powles, T. et al. Durvalumab alone and durvalumab plus Tremelimumab versus chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (DANUBE): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1574–1588. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30541-6 (2020).

Zhao, S. et al. Crosstalk of disulfidptosis-related subtypes, establishment of a prognostic signature and immune infiltration characteristics in bladder cancer based on a machine learning survival framework. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 14, 1180404. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1180404 (2023).

Chen, H., Yang, W., Li, Y., Ma, L. & Ji, Z. Leveraging a disulfidptosis-based signature to improve the survival and drug sensitivity of bladder cancer patients. Front. Immunol. 14, 1198878. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1198878 (2023).

Rui, R., Zhou, L. & He, S. Cancer immunotherapies: advances and bottlenecks. Front. Immunol. 14, 1212476. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1212476 (2023).

Rhea, L. P., Mendez-Marti, S., Kim, D. & Aragon-Ching, J. B. Role of immunotherapy in bladder cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 26, 100296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctarc.2020.100296 (2021).

van Dorp, J. & van der Heijden, M. S. The bladder cancer immune micro-environment in the context of response to immune checkpoint Inhibition. Front. Immunol. 14, 1235884. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1235884 (2023).

Bao, L. et al. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis indicates UCHL5 as a novel cancer biomarker and promotes cervical cancer progression through the Wnt signaling pathway. Biol. Direct. 19, 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13062-024-00588-6 (2024).

Behnam Azad, B. et al. Targeted imaging of the atypical chemokine receptor 3 (ACKR3/CXCR7) in human cancer xenografts. J. Nucl. Med. 57, 981–988. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.115.167932 (2016).

Yang, H. J., Liu, T. & Xiong, Y. Anti-cancer effect of LINC00478 in bladder cancer correlates with KDM1A-dependent MMP9 demethylation. Cell. Death Discov. 8, 242. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-022-00956-z (2022).

Jiang, B. et al. Platelet-derived growth factor-D promotes colorectal cancer cell migration, invasion and proliferation by regulating Notch1 and matrix metalloproteinase-9. Oncol. Lett. 15, 1573–1579. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2017.7510 (2018).

Wen, J., Li, H. Z., Ji, Z. G., Yan, W. G. & Shi, B. B. Expressions of receptor tyrosine kinases mRNA and protein in carcinoma of bladder. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao 33, 393–396. https://doi.org/10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2011.04.009 (2011).

Jin, K. et al. Development of prognostic signature based on immune-related genes in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: bioinformatics analysis of TCGA database. Aging (Albany NY) 13, 1859–1871. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.103787 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. CD8+ T cell co-expressed genes correlate with clinical phenotype and microenvironments of urothelial cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 553399. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.553399 (2020).

Mo, X. et al. A novel pyroptosis-related prognostic LncRNAs signature, tumor immune microenvironment and the associated regulation axes in bladder cancer. Front. Genet. 13, 936305. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.936305 (2022).

Tong, H. et al. An epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related long noncoding RNA signature correlates with the prognosis and progression in patients with bladder cancer. Biosci. Rep. 41. https://doi.org/10.1042/bsr20203944 (2021).

Shen, C. et al. The analysis of PTPN6 for bladder cancer: an exploratory study based on TCGA. Dis. Markers. 2020, 4312629. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4312629 (2020).

Park, H., Kim, Y., Lim, Y., Han, I. & Oh, E. S. Syndecan-2 mediates adhesion and proliferation of colon carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29730–29736. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M202435200 (2002).

Contreras, H. R. et al. The expression of syndecan-1 and -2 is associated with Gleason score and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers, E-cadherin and beta-catenin, in prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. 28, 534–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.03.018 (2010).

Liu, H. et al. Invasion-related circular RNA circFNDC3B inhibits bladder cancer progression through the miR-1178-3p/G3BP2/SRC/FAK axis. Mol. Cancer 17, 161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-018-0908-8 (2018).

Liang, T. et al. Clinical significance and diagnostic value of QPCT, SCEL and TNFRSF12A in papillary thyroid cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 245, 154431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2023.154431 (2023).

Xiao, Y. & Yu, D. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 221, 107753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107753 (2021).

Franklin, R. A. et al. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science 344, 921–925. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1252510 (2014).

Kratochvill, F. et al. TNF counterbalances the emergence of M2 tumor macrophages. Cell. Rep. 12, 1902–1914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.033 (2015).

Le, D. T. et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2509–2520. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1500596 (2015).

Cantley, L. C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 296, 1655–1657. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.296.5573.1655 (2002).

Xie, Y. et al. PI3K/Akt signaling transduction pathway, erythropoiesis and Glycolysis in hypoxia (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 19, 783–791. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2018.9713 (2019).

López-Knowles, E. et al. PIK3CA mutations are an early genetic alteration associated with FGFR3 mutations in superficial papillary bladder tumors. Cancer Res. 66, 7401–7404. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-06-1182 (2006).

Dickstein, R. J. et al. Autophagy limits the cytotoxic effects of the AKT inhibitor AZ7328 in human bladder cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 13, 1325–1338. https://doi.org/10.4161/cbt.21793 (2012).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hewei Zhang and Haibo Yu conceptualized the study and revised the manuscript critically. The cell experiment was conducted by Guangjia Lv and Hengyue Zhu. The data collection and analysis were completed by Yangyang Guo and Ke Yin. Shenchao Guo and Guangjia Lv co-wrote the original manuscript draft. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Wenzhou Central Hospital and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Animal protocols including euthanasia methods were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wenzhou Medical University.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, S., Lv, G., Zhu, H. et al. Disulfidptosis related immune genes drive prognostic model development and tumor microenvironment characterization in bladder urothelial carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 8130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92297-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92297-x