Abstract

This study presents a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis of heat transfer and pressure drop in a straight slot impingement jet, utilizing \(\:\text{T}\text{i}{\text{O}}_{2}/{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\) nanofluid within a square duct. The working fluid comprises \(\:\text{T}\text{i}{\text{O}}_{2}\) nanoparticles (diameter dp = 25 nm) suspended in water at a volume fraction (ϕ) of 2.5%. The investigation of different values of Reynolds numbers (Re) from 8,000 to 17,000, with variations in different geometrical parameters such as slot jet height ratio (\(\:{\text{H}}_{\text{j}\text{e}\text{t}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\): 0.3–0.6), spanwise pitch ratio (\(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{s}\text{p}\text{a}\text{n}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\): 0.18–0.45), and streamwise pitch ratio (\(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{s}\text{t}\text{r}\text{e}\text{a}\text{m}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\): 0.88–1.30). Three-dimensional numerical simulations are conducted using the ANSYS CFD module, incorporating the RNG k-ε turbulence model to solve governing equations in a turbulent regime. The CFD results show strong agreement with both the experimental results and empirical correlations results with similar geometrical configurations and flow conditions for a plain-wall square duct. The deviations are around 6% for the Nusselt number (\(\:{\text{N}\text{u}}_{\text{j}\text{e}\text{t}}\)) and 3% for the friction factor (\(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{j}\text{e}\text{t}}\)), demonstrating the reliability of the CFD model. The \(\:\text{T}\text{i}{\text{O}}_{2}/{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\) nanofluid exhibits a notable enhancement in heat transfer performance compared to pure water. Variations in \(\:{\text{H}}_{\text{j}\text{e}\text{t}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\), \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{s}\text{p}\text{a}\text{n}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\) and \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{s}\text{t}\text{r}\text{e}\text{a}\text{m}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\) significantly influence \(\:{\text{N}\text{u}}_{\text{j}\text{e}\text{t}}\), with the optimal configuration (\(\:{\text{H}}_{\text{j}\text{e}\text{t}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\) = 0.5, \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{s}\text{p}\text{a}\text{n}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\) = 0.3, \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{s}\text{t}\text{r}\text{e}\text{a}\text{m}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\) = 0.97) yielding the highest heat transfer enhancement across most Reynolds numbers. The thermohydraulic performance parameter (THPP) ranges from 0.97 to 1.04, reaching its peak at Re = 8,000 for \(\:{\text{H}}_{\text{j}\text{e}\text{t}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\)= 0.5, \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{s}\text{p}\text{a}\text{n}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\) = 0.3, \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{s}\text{t}\text{r}\text{e}\text{a}\text{m}}/{\text{D}}_{\text{h}\text{d}}\)= 0.97. These findings highlight the potential of impingement jet cooling with nanofluids for thermal management in industrial applications, offering enhanced heat transfer efficiency through direct fluid impact on target surfaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The jet impingement heat transfer (HT) technology has garnered global interest due to its potential for cooling industrial applications since it offers remarkable HT qualities1. The technique of jet impingement on a hot surface is a method that can be utilized in a variety of applications to enhance heat transfer. It is important to apply a significant amount of heating or cooling to attain good thermal performance1] and [2. Through the application of the impinging technique, the air is directed vertically onto a cooling plane through the utilization of spherical or slotted nozzles. The impingement approach is superior to other ways in terms of the rate of HT since it considerably increases the rate3,4,5.

Impinging technology is utilized for chilling stored material during production, heating optical surfaces to reduce fog, and cooling electronic equipment6. Industries use liquid jet impingement for cooling engines, high-power density electronic devices, and treat metals7,8,9,10.

The enhancement of heat transfer in heat exchangers has been extensively studied through both experimental and numerical investigations. This research aims to achieve energy savings, reduce material usage, and develop compact, cost-effective heat exchangers.

The use of swirl generators or turbulators enhances heat transfer11, thereby improving the heat exchanger efficiency across various systems, including solar air heaters12, photovoltaic panels, turbine blades, and combustion chambers13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

Furthermore, Cheng et al.21 zest for compact heat exchangers led to the development of techniques to enhance thermal performance across many industries. The use of vortex generators (VGs) enhances the cooling rate in the heat exchanger channel. The vortex generators initiate the jet flow impinging on the channel wall, enhancing the HT rate by disrupting the boundary layer. There are various vortex generator configurations for thermal performance enhancement displayed in literature reviews4,22,23,24,25.

Various investigators conducted Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to comprehend the flow behaviour in the channel26,27] and [28. Nanofluids have been the subject of extensive thermal domain research. Out of many types of nanofluids, \(\:\text{C}\text{u}\), \(\:\text{C}\text{u}\text{O}\), \(\:{\text{A}\text{l}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{3}\), and \(\:\text{T}\text{i}{\text{O}}_{2}\) nanofluids have gained meaningful interest among researchers17,29,30,31,32,33] and [34.

Salhi et al.35 investigated the impact of cooling fluid thermophysical properties on heat transfer in a circular channel with forced turbulent flow and uniformly heated walls. Nanofluids, based on water with Al₂O₃ or ZnO nanoparticles (1–3% concentration, 30–60 nm diameter), are analyzed at Reynolds numbers between 50,000 and 100,000. Results show that increasing nanoparticle concentration enhances thermal efficiency, confirming nanofluids as superior heat transfer fluids for cooling systems.

Numerical simulations of an impingement cooling system using \(\:{\text{A}\text{l}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{3}\)/water nanofluid for different Reynolds number, channel height, and nanoparticle percentages was examined by Lam & Prakash36, . Experimental and numerical studies have examined the heat transfer and flow structure of a nanofluid in a jet impinging on a flat plate. Water with \(\:{\text{A}\text{l}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{3}\)works. The results spanned Reynolds numbers from 3000 to 32,000 and nanofluid volume fractions from 0 to 10%. As the nanoparticle fraction increases, the convective heat transfer coefficient increases compared to pure water, as demonstrated by Teamah et al.37.

For Reynolds numbers 1600–9400, water and nanofluids having \(\:CuO\) concentrations of 2.0- 4.0% by volume were compared. According to experimental results, base fluid has lower Nusselt numbers than nanofluids with values of concentrations of 2.0 and 3.0% by volume, whereas the inverse is true for the nanofluid with a concentration of 4.0%, as demonstrated by Wongcharee et al.38. The flow properties in the heat sink and the heat transfer caused by the TiO2 nanofluids jet impingement are investigated experimentally. The obtained results by Naphon et al.39 demonstrated that, at a concentration of 0.015% nanofluids, the nanoparticle suspension in base fluid greatly enhances the heat transfer rate by 18.56%. A circular nanofluid jet impingement is used in the experimental studies to cool an aluminium disk at a steady heat flux. The experimental findings demonstrate that the jet impinging for cooling the system fetches heat transfer efficiency of higher order by the Cu2O nanofluid as demonstrated by Amjadian et al.40. An investigation numerically of jet impingement employing several binary hybrid nanofluids to cool a flat plate at a constant temperature. When Al2O3 and MgO nanoparticle configurations were used, the performance was significantly increased. The shapes of the nanoparticles were spherical and platelet, respectively as demonstrated by Boudraa et al.41. Table 1 shows some previous investigations on nanofluids and impingement jets.

The literature review on heat exchanger duct systems with enhanced nanofluid flow through impingement jets and other techniques of heat transfer enhancement43,44,45,46,47 clearly demonstrates that optimising the size and placement of the jets between the duct and heated plate significantly improves heat transfer and reduces pressure drop in the test section. The purpose of this enquiry is to gain a deeper understanding of the fluid dynamics that lead to improved heat transfer when nanofluid flows through impingement jets. The investigation covers a range of Reynolds numbers, from 8000 to 17,000. As far as the authors know, there is no extensive Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) research available in the open literature on the flow of \(\:Ti{O}_{2}/{H}_{2}O\) nanofluid through impingement jets in a square channel.

CFD domain

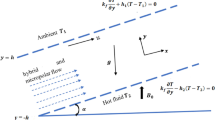

The dimensions of the 3D impingement jet square duct are 108 mm in length, 10 mm in width, and 10 mm in height (total duct height is 20 mm), as shown in Fig. 1: CFD 3D domains of slot impingement jets square duct. The central Sect. (10 mm) of the square duct is subjected to impingement jets, and a heated plate is mounted to the top of the duct, uniformly applying a heat flux of 10kW/m2. The other side selected was considered to be insulated and plane wall. In the current investigation, the k-epsilon model46is used to analyze impingement jets nanofluid flow square duct at various flow parameters value. TiO2/H2O with constant the value of nanoparticle diameter (dp) 25 nm and volume fraction (ϕ) is 2.5% is employed as the working fluid. The Reynolds number (Re) varies from 8000 to 17,000, slot jet height ratio \(\:({H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd})\) varies from 0.3 to 0.6, the spanwise jet pitch ratio \(\:({P}_{span}/{D}_{hd})\) ranges from 0.18 to 0.23 and streamwise jet pitch ratio \(\:({P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd})\) ranges from 0.88 to 0.97. Figure 2 shows a flowchart depicting the workflow of a CFD simulation process, particularly focused on jet impingement analysis.

CFD simulation

This study used a three-dimensional CFD simulation to evaluate heat transfer and calculate friction factors. This was done with the popular commercial software ANSYS 19.3. The equations for incompressible fluids are48,49,50,51,52:

Continuity equation:

The equation of momentum:

Energy equation:

In order to simulate turbulence using the Reynolds-averaged approach, it is necessary to accurately calculate the Reynolds stresses, \(\:-\rho\:\overline{{u}_{i}^{{\prime\:}}}\overline{{u}_{j}^{{\prime\:}}}\) in Eq. (2)49,50,51,52.

The term for turbulent viscosity \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) can be determined using an appropriate turbulence model. The turbulent viscosity is defined by its appearance48,49,50,51,52] and [53.

The transport equations for \(\:k\) and \(\:\epsilon\:\) are54,55:

where \(\:{G}_{k}=-\rho\:\overline{{u}_{i}^{{\prime\:}}{u}_{j}^{{\prime\:}}}\frac{\partial\:{u}_{i}}{\partial\:{u}_{j}}\:\:\:\)presents the production of turbulent kinetic energy. The model constant values are \(\:{C}_{\mu\:}=0.09\), \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{k}}=1.00\), \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{{\upepsilon\:}}=1.30\), \(\:{C}_{1\epsilon\:}\)=1.44 and \(\:{C}_{2\epsilon\:}\)=1.9254,55.

Grid independency test

ANSYS meshes the domain. Grid systems are schematically shown in Fig. 3. Seven grid densities (4048325, 4394365, 4524324, 4729223, 4914879, 5021223, and 5109453) are used to identify the appropriate mesh size for near-wall treatment. The wall distance, denoted as \(\:{y}^{+}\), is a factor in determining the suitable near-wall treatment. To determine the optimal grid density, we conduct a grid test by gradually increasing the density until a further improvement yields a difference of less than 2% between two successive data sets. By meticulously utilising seven grid densities, we find that, at Re = 14,000, the relative variance of the average Nusselt number between solutions involving 4,914,879 and 5,109,453 element cells is less than 2%. Thus, for all situations that are being evaluated, the mesh with 4,914,879 cells and a spacing of \(\:{y}^{+}\approx\:\)2 near the wall elements have been chosen. The square duct and impingement jets mesh in Fig. 3.

Data reduction and thermophysical properties of nanofluid

The values are derived using established relationships found in the literature, including the Reynolds number, Nusselt number, and pressure drop29,56,57,58,59.

The \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is determined through the utilization of the subsequent equation:

The \(\:{f}_{jet}\) is determined through the utilization of the subsequent equation:

The THP is determined through the utilization of the subsequent equation:

The \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{p}}\) represents the thermal-hydraulic performance of a square channel.

The formulae for NF thermophysical characteristics are below29,56,57,58,59:

Density of NF

Specific heat of NF:

Viscosity of NF:

Thermal conductivity of NF

and \(\:{\text{k}}_{\text{B}\text{r}\text{o}\text{w}\text{n}\text{i}\text{a}\text{n}}=5\:\times\:\:{10}^{4}{\upbeta\:}{\upvarphi\:}{{\uprho\:}}_{\text{B}\text{F}}{\text{C}}_{\text{p},\text{B}\text{F}}\sqrt{\frac{\text{K}\text{T}}{{{\uprho\:}}_{{\text{N}\text{P}}_{\text{t}\text{i}}}{\text{D}}_{{\text{N}\text{P}}_{\text{t}\text{i}}}}}\times\:\:\text{f}\left(\text{T},{\upvarphi\:}\right)\)(15)

Table 2 shows nanoparticle and hybrid nanofluid thermophysical characteristics56.

Validation of CFD models

A careful three-dimensional domain was used for the whole 108 mm test length of the impingement jet’s square duct. For the smooth channel, various researchers have tested turbulence models, including the RNG k-ε model, due to the effectiveness of the k-ε approach. In this study, the RNG k-ε model is used for its superior accuracy and reliability in capturing turbulent flow characteristics, particularly in free jets and recirculating flows46,48,57,60. The 3-D full-length square channel solution domain requires significant computational work. Figure 4 (a-b) displays the CFD analysis comparing the Nusselt number and friction factor across different Reynolds number ranges. The study utilizes the RNG k-epsilon turbulence model61 and contrasts its findings with established correlations, including the Dittus-Boelter equation (Nuss=0.023Re0.8Pr0.4)26,62,63 and the Blasius equation for friction factor (fss=0.316Re− 0.25)63,64. Additionally, the results are compared with the experimental data and standard correlation data for a smooth wall. The findings indicate that the CFD results very close the experimental and standard correlation results for plain wall square duct and showing an average absolute deviation of approximately 6% for the Nusselt number and 3% for the friction factor. The CFD results obtained using the RNG k-ϵ turbulence model for the square duct without an impingement jet demonstrate strong agreement with both experimental data and standard correlations. This consistency indicates the turbulence model reliability in predicting flow characteristics within such impingement jet geometries.

A thorough computational fluid dynamics (CFD) study was carried out at different flow parameters to examine the effect of \(\:Ti{O}_{2}/{H}_{2}O\) nanofluid on the \(\:{Nu}_{ss}\).\(\:\:{Nu}_{ss}\) fluctuation at different Reynolds numbers in a square duct filled with water and \(\:Ti{O}_{2}/{H}_{2}O\) is illustrated in Fig. 4(c). The CFD findings show that the base fluid heat transfer is improved when titanium oxide nanoparticles are used because of their increased thermal conductivity. The usage of nanofluid is justified since, as anticipated, the \(\:{Nu}_{ss}\) increases dramatically across the whole range of Re. For a certain range of Reynolds numbers in a square duct without impingement, Fig. 4(d) shows the values of the \(\:{f}_{ss}\) using water and \(\:Ti{O}_{2}/{H}_{2}O\) nanofluid. The results demonstrate that within the whole Reynolds number range, the use of \(\:Ti{O}_{2}/{H}_{2}O\) nanofluid leads to higher \(\:{f}_{ss}\) than pure water.

Results and discussion

The analysis of straight slot impingement jets in a square channel with \(\:Ti{O}_{2}/{H}_{2}O\) nanofluid is carried out for the determination of thermal and friction characteristics. The geometric parameters varied are the jet height ratio (\(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\)), span-wise pitch (\(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\)) and the stream-wise pitch (\(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\)). The flow Reynolds number is varied from 8000 to 17,000. The present section elaborates the findings in terms of \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) and \(\:{f}_{jet}\).

The effect of the jet height ratio (\(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\)) on the \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is shown in Fig. 5 (a) with varying Reynolds number. As predicted the \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) increases with boosting the Re magnitude. It is observed that the \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is enhanced as the \(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\) is varied from 0.3 to 0.5 and attains the maximum \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) at this level. Any further increase in the \(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\) value beyond 0.5, the \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) decreases due to the lowering of heat transfer from the heated surface. The probable reason for the visible trend is the intensity of the jet impingement on the heated surface. At a larger distance (\(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}=0.3\)) of jet release and the target plate, the fluid intensity impinging the heated surface is low and it keeps on escalating as the distance is reduced (\(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}=0.5\)). Whereas the reduction of the distance between the jet and the surface to a very low value leads to a very high velocity jet impinging the surface and rebounding from the heated surface. This rebounding lowers the span of the jet fluid on the surface, thus a reduction in the heat transfer rate is seen.

The effect of the jet height ratio (\(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\)) on the \(\:{f}_{jet}\) is shown in Fig. 5 (b) with varying Reynolds number (\(\:Re\)). It is visible from the figure that there is a significant effect of jet height on the \(\:{f}_{jet}\) produced inside the square duct. The magnitude of the \(\:{f}_{jet}\) is seen to continuously increase with an increase in the \(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\) value from 0.3 to 0.6 and attains the highest magnitude of \(\:{f}_{jet}\). This increase in the \(\:{f}_{jet}\) is seen because as the fluid jet released from the opening hits the heated surface, the impinging velocity directly affects the turbulence intensity. At a higher distance between the jet and the surface, the intensity of fluid impinging is low, and it fetches a lower pressure drop penalty. Whereas, as this distance is reduced (\(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}=0.6\)), the impinging intensity is extremely high which creates high turbulence and rebounding of the fluid from the impinging surface. Also, this rebounding of the fluid provides a resistance in the direction of the cross-fluid flow that leads to a higher pressure drop penalty.

The influence of the relative span-wise pitch (\(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\)) on the \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is displayed in Fig. 6 (a) for a selected Reynolds number range. The magnitude of \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is seen to continuously grow with elevating \(\:Re\). It is seen that \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is boosted as the \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) is varied from 0.18 to 0.45 and attains the maximum \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) at this level. The significance of the \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) for \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\)It is crucial to determine the jet numbers attached to the plate for releasing the fluid to enhance the heat transfer rate. At lower \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.18, there are higher number of jets on the fluid-releasing plate and as the \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) increases to 0.30, the number of jets decreases, but the heat transfer rate is enhanced. This is because of spanwise spacing between the jets. At lower spacing the vortex formed by a jet is overlapped by the neighbouring jets, thus reducing the turbulence intensity that results in lower \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\). Whereas at a higher span-wise spacing, the number of jets on the surface is reduced due to a larger pitch, hence low fluid release results in a reduced heat transfer rate. The optimum \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.3 delivers the highest \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) as it does not overlap the vortices formed by the adjoining jets and has a good number of jets for fluid release.

The \(\:{f}_{jet}\) characteristics of the square duct for relative span-wise pitch (\(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\)) is displayed in Fig. 6(b) for varying Reynolds number. The figure reveals that the span-wise pitch (relative span-wise pitch (\(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\)) when increased from 0.18 to 0.45 fetched a continuously reducing \(\:{f}_{jet}\). It is obvious that at a lower pitch, \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.18, the large number of fluid-releasing jets can be incorporated on the jet plate. A large number of jets will lead to opening a larger area for the fluid to be released from the jet plate, which requires a lower pressure drop across the test section. Increasing the spanwise pitch will reduce the number of jets on the plate, and hence, the open area available for fluid release is reduced; this imposes a higher pressure drop penalty on the system for releasing the fluid over the heated surface.

The effect of the relative stream-wise pitch (\(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\)) on the \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is portrayed in Fig. 7 (a) for a range of selected Reynolds number (\(\:Re\)). The magnitude of \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) increases with an increase in \(\:Re\). The plot reveals that the \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is increased as the \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) is varied from 0.88 to 1.30 and the maximum \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is achieved at this position. The magnitude of \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) for determining \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) is crucial, as it establishes the number of jets attached on the jet plate for enhancing the heat transfer rate in the streamwise direction. At lower \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.88, there are large fluid jets on the jet plate and as the \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) increases to 0.97, the number of jets decreases but in turn the heat transfer rate is enhanced. This trend is seen as a lower streamwise pitch, the impinging area on the heated surface overlaps each other and thus reduces the turbulence intensity. For a higher stream-wise spacing, the number of jets on the surface is reduced due to increased pitch dimension, which in turn delivers a low amount of fluid for impingement. Thus, a reduced heat transfer rate is seen. The optimum \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.97 has the feature of providing maximum turbulence that fetches highest \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\).

The effect of relative stream-wise pitch (\(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\)) on \(\:{f}_{jet}\) characteristics of the square duct is displayed in Fig. 7(b) for varying Reynolds number. It is observed that relative stream-wise pitch (\(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\)) when increased from 0.88 to 1.30 fetched a continuous increase in \(\:{f}_{jet}\). It is evident that for lower pitch, \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.88, the attached jets on the surface are higher in number. The large number of jets will release high fluid from these jets for fluid to be released for cooling that requires lower pressure drop across the test section. While increasing the streamwise pitch will lower the number of jets on the jet plate and hence the jet area available for fluid release is reduced. The lower number of jets in turn imposes a larger resistance in the fluid flow direction these concepts can observed in Figs. 8, 9 and 10.

The thermohydraulic performance (\(\:THP\)) of the square duct with straight slot impingement jets with the \(\:Ti{O}_{2}/{H}_{2}O\) nanofluid is analysed to determine the combined effect of the heat transfer and the friction factor. It is required to integrate and study the combined effect of a square duct with straight slot impingement jets to fetch the optimum value of parameters that deliver a higher heat transfer rate with minimum possible pressure drop penalty. The \(\:THP\) values yielded for different geometric parameters viz. Relative jet height (\(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\)), Relative spanwise pitch (\(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\)) and the relative streamwise pitch (\(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\)) is displayed in Fig. 11(a), 11(b) and 11(c), respectively. The maximum magnitude of the \(\:THP\) is yielded for \(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.5, \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.3 and \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.97 at Reynolds number of 8000 for all sets of parameters.

Conclusions

In the present study, the thermal performance of a straight slot jet using \(\:Ti{O}_{2}/{H}_{2}O\) nanofluid as the working fluid within a square channel is analyzed through CFD simulations. The RNG k-ε turbulence model is employed to generate results by varying key parameters, including Reynolds number (Re) from 8000 to 17,000, slot jet height ratio \(\:({H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd})\) from 0.3 to 0.6, spanwise jet pitch ratio \(\:({P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd})\) from 0.18 to 0.45, and streamwise jet pitch ratio \(\:({P}_{span}/{D}_{hd})\) from 0.88 to 1.30. The findings from the obtained results are presented below.

-

The value of \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) increases as the slot jet height ratio (\(\:({H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd})\) rises up to 0.5. However, beyond this point, any further increase in \(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\) leads to a decrease in the \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\). On the other hand, the jet friction factor \(\:{f}_{jet}\) continues to increase with \(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\), reaching its maximum value at \(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\)=0.6.

-

The value of \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) rise with a rise in spanwise jet pitch \(\:({P}_{span}/{D}_{hd})\) value of 0.3, and with a further upsurge in the value of \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\), \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) reductions. However, \(\:{f}_{jet}\) upsurges with a reduction in \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) and attain the highest value corresponding to the \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) value of 0.45.

-

\(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) rise with the rise in streamwise jet pitch \(\:({P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd})\) value of 0.97, and with a further increase in the value of \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\), \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) decreases. However, \(\:{f}_{jet}\) increases with a decrease in \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) and attain the highest value corresponding to the \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) value of 1.30.

-

The THP results reveal that the optimal thermal and hydraulic performance consistently occurs at a Reynolds number of 8000. In the first configuration, the maximum total hydraulic power (THP) is achieved at a relative jet height \(\:{H}_{jet}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.5. The second configuration demonstrates the best performance at a relative spanwise pitch \(\:{P}_{span}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.3, while the third configuration reaches peak THP at a relative streamwise pitch \(\:{P}_{stream}/{D}_{hd}\) of 0.97.

Future research possibility

Jet impingement cooling using nanofluids has the potential to enhance thermal regulation in high-power electronic devices and other industrial applications. There are promising research opportunities in understanding how jet configurations, particularly the spacing between jets and the distance from the nozzle to the plate, impact both heat transfer and fluid dynamics in multi-jet impingement setups.

Future studies could refine computational models to better predict and optimize the efficiency of nanofluids and advanced hybrid nanofluids in these cooling systems. Depending on the shape, size, and concentration of nanoparticles used, attaching ribs or baffles beneath the heated surface in square ducts might further improve heat dissipation.

Hybrid nanofluids, which combine different types of nanoparticles, present another avenue for boosting cooling performance in industrial settings, offering the potential for more effective and energy-efficient thermal management solutions.

Data availability

Data will be available on request. Corresponding author, Dr Tabish Alam will be contacted for data availability on the following email, tabish.iitr@gmail.com.

Change history

01 May 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98479-x

Abbreviations

- D hd :

-

Hydraulic dia

- dp:

-

Nanoparticle dia, mm

- \(\:{H}_{jet}\) :

-

Height of jet, mm

- \(\:{P}_{stream}\) :

-

Streamwise jet pitch, mm

- \(\:{P}_{span}\) :

-

Spanwise jet pitch, mm

- \(\:\text{R}\text{e}\) :

-

Reynolds number

- \(\:{Nu}_{ss}\) :

-

Nusselt number of smooth

- \(\:{Nu}_{jet}\) :

-

Nusselt number of impingement jet

- \(\:{f}_{ss}\) :

-

Friction factor of friction factor

- \(\:{f}_{jet}\) :

-

Friction factor of impingement jet

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- HT:

-

Heat transfer

- THP:

-

Thermohydraulic performance

References

Barewar, S. D. et al. Optimization of jet impingement heat transfer: A review on advanced techniques and parameters, Mar. 01, Elsevier Ltd. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsep.2023.101697

Srivastav, A., Maithani, R. & Sharma, S. Innovative impinging jet methods for performance enhancement: a review, J Therm Anal Calorim, Nov. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-024-13777-2

Plant, R. D., Friedman, J. & Saghir, M. Z. A review of jet impingement cooling. Int. J. Thermofluids. 17 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijft.2023.100312 (Feb. 2023).

Balla, H. H., Hashem, A. L., Kareem, Z. S. & Abdulwahid, A. F. Heat transfer potentials of ZnO/water nanofluid in free impingement jet. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 27 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2021.101143 (Oct. 2021).

Jalali, E., Akbari, O. A., Sarafraz, M. M., Abbas, T. & Safaei, M. R. Heat transfer of oil/mwcnt nanofluid jet injection inside a rectangular microchannel. Symmetry (Basel). 11 (6). https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11060757 (Jun. 2019).

Salhi, J. E. et al. Turbulence and thermo-flow behavior of air in a rectangular channel with partially inclined baffles, Energy Sci Eng, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 3540–3558, Sep. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.1239

Yousefi, T., Shojaeizadeh, E., Mirbagheri, H. R., Farahbaksh, B. & Saghir, M. Z. An experimental investigation on the impingement of a planar jet of Al2O3-water nanofluid on a V-shaped plate, Exp Therm Fluid Sci, vol. 50, pp. 114–126, Oct. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2013.05.011

Nadda, R., Kumar, A. & Maithani, R. Efficiency improvement of solar photovoltaic/solar air collectors by using impingement jets: A review, Oct. 01, Elsevier Ltd. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.05.025

Nadda, R., Kumar, A. & Maithani, R. Developing heat transfer and friction loss in an impingement jets solar air heater with multiple Arc protrusion Obstacles. Sol. Energy. 158, 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2017.09.042 (2017).

Tie, P., Li, Q. & Xuan, Y. Heat transfer performance of Cu-water nanofluids in the jet arrays impingement cooling system, International Journal of Thermal Sciences, vol. 77, pp. 199–205, Mar. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2013.11.007

Salhi, J. E. et al. Three-dimensional analysis of the impact of wall roughness with micro-pines on thermo-hydrodynamic behavior, Energy Ecol Environ, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 157–177, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-023-00269-6

Salhi, J. E., Zarrouk, T. & Taoukil, D. Parametric analysis for optimizing performance of solar air heating systems with innovative rib configurations. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 158 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.107869 (Nov. 2024).

Nakharintr, L., Naphon, P. & Wiriyasart, S. Effect of jet-plate spacing to jet diameter ratios on nanofluids heat transfer in a mini-channel heat sink. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 116, 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.09.037 (2018).

Javidan, M. & Moghadam, A. J. Effective cooling of a photovoltaic module using jet-impingement array and nanofluid coolant. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 137 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106310 (Oct. 2022).

Mitra, S., Saha, S. K., Chakraborty, S. & Das, S. Study on boiling heat transfer of water-TiO 2 and water-MWCNT nanofluids based laminar jet impingement on heated steel surface. Appl. Therm. Eng. 37, 353–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.11.048 (May 2012).

Sun, B., Zhang, Y., Yang, D. & Li, H. Experimental study on heat transfer characteristics of hybrid nanofluid impinging jets, Appl Therm Eng, vol. 151, pp. 556–566, Mar. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.01.111

Ajeel, R. K., Fayyadh, S. N., Ibrahim, A., Sultan, S. M. & Najeh, T. Comprehensive analysis of heat transfer and pressure drop in square multiple impingement jets employing innovative hybrid nanofluids. Results Eng. p. 101858 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101858 (Feb. 2024).

Sun, B., Qu, Y. & Yang, D. Heat transfer of single impinging jet with Cu nanofluids. Appl. Therm. Eng. 102, 701–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.03.166 (Jun. 2016).

Atofarati, E. O., Sharifpur, M. & Meyer, J. Hydrodynamic effects of hybrid nanofluid jet on the heat transfer augmentation. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 51 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2023.103536 (Nov. 2023).

Kareem, Z. S., Balla, H. H. & Abdulwahid, A. F. Heat transfer enhancement in single circular impingement jet by CuO-water nanofluid. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 15 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2019.100508 (Nov. 2019).

Cheng, J., Xu, H., Tang, Z. & Zhou, P. Multi-objective optimization of manifold microchannel heat sink with corrugated bottom impacted by nanofluid jet. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 201 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123634 (Feb. 2023).

Boonloi, A. & Jedsadaratanachai, W. Turbulent forced convection in a heat exchanger square channel with wavy-ribs vortex generator, Chin J Chem Eng, vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 1256–1265, Aug. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2015.04.001

Moon, M. A., Park, M. J. & Kim, K. Y. Evaluation of heat transfer performances of various rib shapes. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 71, 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.12.026 (Apr. 2014).

Farajollahi, B., Etemad, S. G. & Hojjat, M. Heat transfer of nanofluids in a shell and tube heat exchanger. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 53, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2009.10.019 (2010).

Wongcharee, K. & Eiamsa-ard, S. Heat transfer enhancement by using CuO/water nanofluid in corrugated tube equipped with twisted tape. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 39 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2011.11.010 (2012).

Singh, I. & Singh, S. CFD analysis of solar air heater duct having square wave profiled transverse ribs as roughness elements. Sol. Energy. 162, 442–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOLENER.2018.01.019 (Mar. 2018).

Srivastav, A., Maithani, R. & Sharma, S. Influence of nozzle profile on submerged pipe jet impingement heat transfer. Exp. Heat Transf. https://doi.org/10.1080/08916152.2024.2391803 (2024).

Yadav, A. S. & Bhagoria, J. L. A CFD based thermo-hydraulic performance analysis of an artificially roughened solar air heater having equilateral triangular sectioned rib roughness on the absorber plate, Int J Heat Mass Transf, vol. 70, pp. 1016–1039, Mar. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.11.074

Kristiawan, B., Wijayanta, A. T., Enoki, K., Miyazaki, T. & Aziz, M. Heat transfer enhancement of TiO2/water nanofluids flowing inside a square minichannel with a microfin structure: A numerical investigation. Energies (Basel). 12 (16). https://doi.org/10.3390/en12163041 (2019).

Kumar, S., Kothiyal, A. D., Bisht, M. S. & Kumar, A. Effect of nanofluid flow and protrusion ribs on performance in square channels: an experimental investigation. J. Enhanced Heat. Transf. 26 (1). https://doi.org/10.1615/JEnhHeatTransf.2018026042 (2019).

Tan, Z., Jin, P., Zhang, Y. & Xie, G. Flow and thermal performance of a multi-jet twisted square microchannel heat sink using CuO-water nanofluid. Appl. Therm. Eng. 225 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.120133 (May 2023).

Ho, C. J., Chen, M. W. & Li, Z. W. Numerical simulation of natural convection of nanofluid in a square enclosure: effects due to uncertainties of viscosity and thermal conductivity. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 51, 17–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2007.12.019 (2008).

Kumar, S., Kothiyal, A. D., Bisht, M. S. & Kumar, A. Effect of ratio of protrusion height to print diameter on thermal behaviour of Al2O3–H2O nanofluid flow in a protrusion obstacle square channel. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5903-2_30 (2018).

He, Z. et al. Theoretical exploration of heat transport in a stagnant power-law fluid flow over a stretching spinning porous disk filled with homogeneous-heterogeneous chemical reactions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 50 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2023.103406 (Oct. 2023).

Salhi, J. E., Zarrouk, T. & Salhi, N. Numerical analysis of the properties of nanofluids and their impact on the thermohydrodynamic phenomenon in a heat exchanger, in Materials Today: Proceedings, Elsevier Ltd, pp. 7559–7565. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.365

Lam, P. A. K. & Prakash, K. A. Thermodynamic investigation and multi-objective optimization for jet impingement cooling system with Al2O3/water nanofluid. Energy Convers. Manag. 111, 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2015.12.018 (Mar. 2016).

Teamah, M. A., Khairat Dawood, M. M. & Shehata, A. Numerical and experimental investigation of flow structure and behavior of nanofluids flow impingement on horizontal flat plate. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 74, 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2015.12.012 (Jun. 2016).

Wongcharee, K., Chuwattanakul, V. & Eiamsa-ard, S. Influence of CuO/water nanofluid concentration and swirling flow on jet impingement cooling. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 88, 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2017.08.020 (Nov. 2017).

Naphon, P., Nakharintr, L. & Wiriyasart, S. Continuous nanofluids jet impingement heat transfer and flow in a micro-channel heat sink. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 126, 924–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.05.101 (Nov. 2018).

Amjadian, M., Safarzadeh, H., Bahiraei, M., Nazari, S. & Jaberi, B. Heat transfer characteristics of impinging jet on a hot surface with constant heat flux using Cu2O–water nanofluid: An experimental study, International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 112, Mar. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.104509

Boudraa, B. & Bessaïh, R. Numerical investigation of jet impingement cooling an isothermal surface using extended jet holes with various binary hybrid nanofluids. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 127 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2021.105560 (Oct. 2021).

Mohammadpour, J., Salehi, F., Sheikholeslami, M. & Lee, A. A computational study on nanofluid impingement jets in thermal management of photovoltaic panel. Renew. Energy. 189, 970–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.03.069 (Apr. 2022).

Alqarni, M. S., Memon, A. A., Anwaar, H., Usman & Muhammad, T. The forced convection analysis of water alumina nanofluid flow through a 3D annulus with rotating cylinders via κ – ε turbulence model. Energies (Basel). 15 (18). https://doi.org/10.3390/en15186730 (Sep. 2022).

Usman et al. A forced convection of water-aluminum oxide nanofluids in a square cavity containing a circular rotating disk of unit speed with high Reynolds number: A Comsol multiphysics study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 39 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2022.102370 (Nov. 2022).

Usman, M. S., Khan, J., Wang, A. A., Memon & Muhammad, T. Investigating the enhanced cooling performance of ternary hybrid nanofluids in a three-dimensional annulus-type photovoltaic thermal system for sustainable energy efficiency, Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, vol. 60, Aug. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.104700

Srivastav, A., Maithani, R. & Sharma, S. Investigation of heat transfer and friction characteristics of solar air heater through an array of submerged impinging jets. Renew. Energy. 227 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.120588 (Jun. 2024).

Sarkar, I. et al. Application of TiO2 nanofluid-based coolant for jet impingement quenching of a hot steel plate, Experimental Heat Transfer, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 322–336, Jul. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/08916152.2018.1517835

Yadav, A. S. & Bhagoria, J. L. A CFD (computational fluid dynamics) based heat transfer and fluid flow analysis of a solar air heater provided with circular transverse wire rib roughness on the absorber plate, Energy, vol. 55, pp. 1127–1142, Jun. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2013.03.066

Manca, O., Nardini, S. & Ricci, D. A numerical study of nanofluid forced convection in ribbed channels. Appl. Therm. Eng. 37 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.11.030 (2012).

Chekifi, T. & Boukraa, M. CFD applications for sensible heat storage: A comprehensive review of numerical studies, Sep. 15, Elsevier Ltd. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.107893

Hanafi, N. S. M. et al. Numerical simulation on the effectiveness of hybrid nanofluid in jet impingement cooling application, Energy Reports, vol. 8, pp. 764–775, Nov. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.07.096

Safikhani, H. & Abbasi, F. Numerical study of nanofluid flow in flat tubes fitted with multiple twisted tapes. Adv. Powder Technol. 26 (6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2015.09.002 (2015).

Akkurt, N. et al. Analysis of the forced convection via the turbulence transport of the hybrid mixture in three-dimensional L-shaped channel. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 41 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2022.102558 (Jan. 2023).

Shaker, B., Gholinia, M., Pourfallah, M. & Ganji, D. D. CFD analysis of Al2O3-syltherm oil nanofluid on parabolic trough solar collector with a new flange-shaped turbulator model. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 12 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taml.2022.100323 (Feb. 2022).

Lu, H. & Lu, L. A numerical study of particle deposition in ribbed duct flow with different rib shapes, Build Environ, vol. 94, no. P1, pp. 43–53, Dec. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.07.030

Reddy, N. K., Swamy, H. A. K., Sankar, M. & Jang, B. MHD convective flow of Ag-TiO2hybrid nanofluid in an inclined porous annulus with internal heat generation, Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, vol. 42, Feb. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2023.102719

Ghazanfari, V., Taheri, A., Amini, Y. & Mansourzade, F. Enhancing heat transfer in a heat exchanger: CFD study of twisted tube and nanofluid (Al2O3, Cu, CuO, and TiO2) effects, Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, vol. 53, Jan. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2023.103864

Kumar, A. et al. Effect of oval rib parameters on heat transfer enhancement of TiO2/water nanofluid flow through parabolic trough collector. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 55, 104080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.104080 (Mar. 2024).

Yan, J., Song, H., Yang, S. & Chen, X. Effect of heat treatment on the morphology and electrochemical performance of TiO2 nanotubes as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries, Mater Chem Phys, vol. 118, no. 2–3, pp. 367–370, Dec. (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2009.08.007

Kumar, A. et al. Influence of 45oV-type with collective ring turbulence promoters parameters of thermal performance of flat plate heat collector. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 55, 104113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.104113 (Mar. 2024).

Srivastav, A. CFD Investigation of Thermo-hydraulic Performance in Rib Roughened Fin Under Forced Convection, Journal of Graphic Era University, Mar. (2023). https://doi.org/10.13052/jgeu0975-1416.1111

Srivastav, A., Maithani, R. & Sharma, S. Influence of submerged impingement jet designs on solar air collector performance. Renew. Energy. p. 121699 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.121699 (Oct. 2024).

Kumar, A. et al. Nov., Effect of Dimpled Rib with Arc Pattern on Hydrothermal Characteristics of Al2O3-H2O Nanofluid Flow in a Square Duct, Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 22, (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214675

Shui, L., Hu, Z., Song, H., Zhai, Z. & Wang, J. Study on flow and heat transfer characteristics and Anti-Clogging performance of Tree-Like branching microchannels. Energies (Basel). 16 (14). https://doi.org/10.3390/en16145531 (Jul. 2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R999), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anil Kumar: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Conceptualization, MethodologyRajesh Maithani: Investigation, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Sachin Sharma: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - review & editing. Ayushman Srivastav: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - review & editingTabish Alam: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, supervision. Md Irfanul Haque Siddiqui: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, supervision, Resources, Fund AcquisitionDan Dobrotă: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.Nicolae Cofaru : Writing - review & editing, VisulaizationIntesaaf Ashraf: Methodology, Software, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Dan Dobrotă was incorrectly affiliated with ‘Mechanical Engineering Department, UCL, London WC1E, UK’. The correct affiliation is: Faculty of Engineering, Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Sibiu 550024, Romania.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, A., Maithani, R., Sharma, S. et al. Impact of straight slot impingement jets on heat transfer enhancement of TiO2/H2O nanofluid flow in a square channel: CFD analysis. Sci Rep 15, 7728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92303-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92303-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the impact of injection and suction ports on hybrid nanofluid heat transfer enhancement over a heated block: application to electronic chipset thermal management

Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design (2026)