Abstract

In the field of complex networks, understanding the spreading dynamics in multi-layer networks is crucial for real-world applications such as epidemic control and the analysis of social phenomenon. In this study, a two-layer interconnected network is established, with each layer modeled as a small-world network. To investigate the spreading dynamics on this two-layer network, the classic susceptible-infected-susceptible (SIS) model is applied to it. The governing equations for the Infection proportions on each layer are developed first, followed by the proof of the existence of steady solutions (the proportion of finally infected nodes in the network) and their analytical derivation. Then, the computational model is developed accurately track the time evolution of these solutions using the 4th-order Runge–Kutta method. Finally, a numerical investigation on the influence of parameters is carried out. Three categories of parameters are considered, including inter-layer parameters, intra-layer parameters, and recovery-related parameters. Their effects on the steady solution and the infection velocity of the SIS model on the two-layer networks are summarized. It is found that both inter-layer and intra-layer parameters significantly impact the infection dynamics, an increase in these parameters leads to an increase in the final Infection proportions and a decrease in the time to reach this state. For recovery-related parameters, there exists a maximum value due to the balance of contributions from different aspects. Besides, when the scales of the two layers are unequal, the influence of intra-layer parameters is more obvious for the layer with a smaller scale. The study may contribute to the understanding of spreading dynamics on multi-layer complex networks. It provides practical guidance for managing and controlling the spread of infections in real-world scenarios. The insights gained are valuable for related research and applications in areas like epidemiology and social network analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and literature review

Complex networks provide a powerful tool for studying complex systems in the real world, such as the spread of epidemics, the dissemination of public opinion on social networks, and the emergence of consciousness in the brain. By studying the dynamics of spreading on complex networks, we can better understand the intrinsic mechanisms of these complex systems, such as preferences for network links establishment. Therefore, related research on the spreading dynamics of complex networks is numerous in the past decades1,2,3,4,5.

Most research on the dynamics of spreading is primarily based on the classical epidemic models, such as the SI (Susceptible-Infected) model, the SIR (Susceptible-Infected-Recovered) model, and the SIS (Susceptible-Infected-Susceptible) model6. Here, Susceptible (S) indicates the individuals that are healthy but susceptible to a disease; Infected (I) means the individuals are already infected with the disease and can transmit it to susceptible ones; and Recovered (R) represents those which have recovered from the disease and are now immune to it. The basic idea for the models is based on the Markov process, in which each node in the network is in one of the three states at any given time: susceptible, infected, and recovered. Zhang et al.7 investigated the relationships between link-closure strategies and the traffic-driven epidemic spreading with an SI model, and found that the epidemic spreading can be suppressed by the targeted closing of links between small-degree nodes. Zhao et al.8 proposed a novel simplified activity-driven model with memory, and then the authors considered the SIR model and explored how dynamical processes are impacted by the novel model. Li et al.9 investigated the influence of the competition between different travelling strategies on virus propagation with a combined evolutionary game theory and complex network theory method, a classic SIS model was adopted to describe the transmission process.

These above studies are valuable for understanding the dynamic behaviour of complex networks. However, most of them assumed the structure of the network to be a single layer. In reality, various systems are not isolated from each other but are interconnected. An example is the viruses can spread simultaneously within human networks and animal networks, and the two networks may infect each other. Generally, the problem can be described with a human-animal two-layer network. In the network, nodes represent a person or an animal, the intra-layer links indicate the interactions between persons or animals that could facilitate the spread of a disease, and the inter-layer links mean the connections between persons and animals. To analyze the problems of this kind, the multi-layer network theory occurs. Although multi-layer network theory is a relatively recent area of study within complex networks, numerous significant advancements have already been achieved due to its realistic features10,11,12,13,14.

As the research on multi-layer networks gradually deepens, the study of spreading dynamics on multi-layer networks has also gradually emerged. Relatively speaking, the representative two-layer networks are considered by most studies. Wei et al.15 conducted a detailed theoretical analysis on the dynamical behaviors of epidemic spreading over a two-layer interconnected network, and found that the global epidemic threshold in the interconnected network is not larger than the epidemic thresholds for the two isolated layered networks. Bernal et al.16 investigated the controlling of the spreading process on a complex multi-layer network, and a Markov-chain based SIS dynamics is assumed on the network. Wang et al.17 proposed a noval epidemic model to explore the propagation of two competitive information (positive and negative prevention information) on a two-layer complex network. Lin et al.18 studied the networked SIS model coupled with the opinion dynamics, and the epidemic spreading on the multi-layer networks was analyzed.

Although the research on the study of spreading dynamics on multi-layer networks is numerous, the research on the mechanisms of spreading is still not sufficient19. Most of the research mainly focus on the coupling propagation of multi diseases on the single-layer network, and few work can be found for the propagation of a single disease on multi-layer networks that contains different types of agents. Therefore, the spreading dynamics of the SIS model on the two-layer interconnected networks is analyzed in this paper, in order to enrich the understanding of the multi-layer networks. A better understanding of the spreading mechanisms in multi-layer networks can not only enrich the theoretical framework of complex networks, but also contribute to practical applications, including epidemic prevention and control, as well as the prediction and management of information spread.

The paper is organized as follows: Details of the methods used in the paper are given in Section “models and numerical methods”. Then, the results including the analysis of parameters and scales are presented in Section “Results and discussion”. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in Section “Conclusions”.

Models and numerical methods

SIS model on the two-layer network

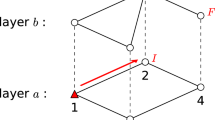

This paper aims to analyze the SIS model on the two-layer complex network, an example is displayed in Fig. 1. The network consists of nodes and links, and the links represent the relationship between the nodes.

The two layers are designated as A and B, which have N and M nodes, respectively. AB refers to the inter-layer links originating from layer A to layer B, whereas BA defines the inter-layer links originating from layer B to layer A.

Many real-world networks, such as social networks, traffic networks and knowledge networks, have high clustering coefficients and short average path lengths, which are typical characters of small-world networks20. Therefore, both layers are assumed to be small-world networks21. The intra-layer network average degrees of layers A and B are labeled as \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\), and the inter-layer network average degrees between layers A and B are \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\), respectively. The networks are assumed to be undirected, so the values of \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) can be obtained by dividing the total number of inter-layer links by the node number of layer A and B.

The classical SIS model is applied to the two-layer network, in which the nodes within the network have two states: susceptible and infected. With \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right)\) and \(\rho^{B} \left( t \right)\) to represent the proportion of infected nodes in the layer A and B, the evolution of the two proportions can be expressed as15:

here \(\lambda_{A}\) and \(\lambda_{B}\) indicate the infection rate of layers A and B, and \(\mu_{A}\) and \(\mu_{B}\) represent the recovery rate of the two layers. \(\lambda_{AB}\) and \(\lambda_{BA}\) means the inter-layer infection rate from layer A to layer B and layer B to layer A, respectively. In fact, the first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (1) denotes the rate of recovery at time \(t\) within a layer, the second term depicts the rate that a node being infected by another node on the same layer, and the third term illustrates the rate of a node being infected by a node from the different layer.

Existence of the solutions

As \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right)\) and \(\rho^{B} \left( t \right)\) represent the proportion of infected nodes in the two layers, and the case of repeated infection is not considered, a reasonable solution of the two variables should fall in [0, 1]. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the existence of solutions. Substituting \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right) = 0\) into the right-hand side of Eq. (1a), it is obtained that \({{{\text{d}}\rho^{A} \left( t \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}\rho^{A} \left( t \right)} {{\text{d}}t}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}t}} = \lambda_{BA} \langle k_{BA} \rangle \rho^{B} \left( t \right)\,\left[ {1 - \rho^{A} \left( t \right)} \right]\), which means \({\text{d}}\rho^{A} \left( t \right)/{\text{d}}t > 0\). Repeat the process, we can get the following relations:

To show the relations more clear, an illustration of the corresponding evolution trend is provided in Fig. 2. It is observed that the solution tends to back when it approaches the boundary. In this way, the evolution process will be limited to [0, 1] until a final steady solution is obtained. Define the steady solution as \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\rho_{\infty }^{B}\), then we have

The values of \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\rho_{\infty }^{B}\) are usually significant as they indicate the proportion of infected nodes in the network. Besides, it is also of concern how long it takes for the network to reach a certain state. These are the two problems that will be studied in the following sections.

Derivation of the steady solutions

In this section, the steady solutions of Eq. (1) are derived analytically. When the solution reaches a steady state, it is obvious that \({\text{d}}\rho \left( t \right)/{\text{d}}t = 0\). Then Eq. (1) are simplified as:

in which \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\rho_{\infty }^{B}\) indicate the steady solution on the two layers.

Assume that the recovery rate of the two layers \(\mu_{A}\) and \(\mu_{B}\) are not zero, Eq. (4) can be further simplified to the following form:

in which

With Eq. (5a), it is easy to express \(\rho_{\infty }^{B}\) with \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\), which is

Substitute Eq. (6) into Eq. (5b), the following equation is obtained with \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) to be the individual unknown value:

In this way, Eq. (4) are transformed in to Eqs. (6) and (7). Equation (7) can be solved with the bisection method, then the value of \(\rho_{\infty }^{B}\) can be obtained with Eq. (6).

Computational methods for the accurate time histories of solutions

To analyze the velocity of infection within the network, accurate time histories of \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right)\) and \(\rho^{B} \left( t \right)\) are necessary. As mentioned before, the governing equations of the two variables are Eq. (1). Considering the form of Eq. (1), the numerical integration method is adopted in the paper. To ease the expression, Eq. (1) are rewritten as:

in which

Considering that Eq. (8) is a typical partial differential equation that varies with time, we can solve it using the Runge–Kutta method. To ensure accuracy, the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method is used to solve Eq. (8). Therefore, Eq. (8) are integrated as:

here

In this way, time histories of the values of \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right)\) and \(\rho^{B} \left( t \right)\) are obtained.

Results and discussion

For most realistic situations, the steady solution (final Infection proportions) and infection velocity (necessary time to reach the final Infection proportions) are usually the most concerning. In this section, the influence of various parameters on the steady solution and infection velocity are analyzed in detail. Considering the form of Eq. (1), parameters are divided into three kinds based on the contribution themselves. \(\lambda_{A}\), \(\lambda_{B}\), \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\), and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) are intra-layer parameters; \(\lambda_{AB}\), \(\lambda_{BA}\), \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\), and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) are inter-layer parameters; and \(\mu_{A}\) and \(\mu_{B}\) are recovery related parameters. Therefore, the influence of the three kinds of parameters will be analyzed numerically. Besides, the scales of the two layers are assumed to be the same for first three sections, and the influence of layer scale will be discussed in the last section.

Before the simulation, some additional remarks are necessary. As the intra-layer transmission rate is usually higher than the inter-layer transmission rate22,23, the values of \(\lambda_{A}\) and \(\lambda_{B}\) are kept 1.0, and that of \(\lambda_{AB}\), \(\lambda_{BA}\) are set as 0.5 for all the following simulations. Since the time histories of \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right)\) and \(\rho^{B} \left( t \right)\) reach the steady solution only when time \(t\) approaches infinity, a characteristic time of TA and TB are defined to represent the infection velocity. The definition of the characteristic time is: when time t reaches the characteristic time, the solution reachs 99% of the steady solution. That is \(\rho^{A} \left( {T_{A} } \right) = 0.99\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\rho^{B} \left( {T_{B} } \right) = 0.99\rho_{\infty }^{B}\) for the two layers, respectively. For all the simulations, the time step is set 0.001 after a convergence test.

Influence of parameters on the two-layer interconnected network with equal scale

When the scales of the two layers are equal, the influences of parameters on \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right)\) and \(\rho^{B} \left( t \right)\) will be similar as Eqs. (1a) and (1b) have the same form. Therefore, only the influences of parameters on \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right)\) are analyzed in the section. The influence rule for \(\rho^{B} \left( t \right)\) can be obtained by simply switch A and B for the results.

Influences of intra-layer parameters

In this section, influences of intra-layer parameters including \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) are analyzed. Due to the small-wold character, \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) should be even numbers. A wide range of 2–30 is adopted for the two parameters, and the values of other variables are set as 1.0 for \(\mu_{A}\) and \(\mu_{B}\), and 2.0 for \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\).

Variation of \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) with \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) is shown in Fig. 3a. To show the results more clear, Fig. 3b presents the variation of \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) with \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) under different \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\), which is the 2D slices of Fig. 3a. As shown in the figures, it is observed that the value of \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) has an obvious influence on \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\). With the increase of \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\), \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) grows gradually but the the rate of growth is gradually decreasing. \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) eventually stabilizes around 0.968 and does not show a significant increase with further addition of \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\). It is the result of achieving a balance between infection and recovery. \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) also grows with the increase of \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\), but the growth is not obvious. It is easy to know that this is normal as \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) can only indirectly affect \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) by the inter-layer network transmission.

Figure 4a shows the variation of TA (characteristic time of \(\rho^{A}\)) with \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\). Again, 2D slices which present the variation of TA with \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) under different \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) are given in Fig. 4b. As shown in Fig. 4b, with the increase of \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\), TA decreases gradually but the the rate of descend is gradually decreasing. When \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) is not so large, the influence of \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) is more obvious than that with a larger \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\). For the case of a large \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\), TA approaches 0.306 and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) does not show a significant influence.

Influences of inter-layer parameters

Now we analyzed the influences of inter-layer parameters \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\). As the scale of the two layers are the same, \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) should be equal. Similar to last section, a wide range of 2–30 is adopted for the two parameters. For the values of other variables, they are set as 1.0 for \(\mu_{A}\) and \(\mu_{B}\), and 2.0 for \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\).

The variation of \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and TA with \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) is shown in Fig. 5. It is observed that with the growth of \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\), \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) gradually increase but TA tends to decrease. The result is reasonable considering the function of \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\). \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) indicates the number of the links between the two layers, a larger \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) means a stronger contribution can be achieved from layer B to layer A. As a result, a larger \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and a smaller TA is obtained.

Influences of recovery-related parameters

Finally, we analyzed the influences of recovery-related parameters \(\mu_{A}\) and \(\mu_{B}\). The intra-layer parameters \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\), and inter-layer parameters \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) are all set as 2.0. For the values of \(\mu_{A}\) and \(\mu_{B}\), a range of 0–3 is adopted.

Variation of \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and TA with \(\mu_{A}\) is shown in Fig. 6. As shown in Fig. 6a, \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) decreases linearly as \(\mu_{A}\) increases. The results is reasonable as \(\mu_{A}\) contributes negatively for \(\rho^{A} \left( t \right)\), as shown in Eq. (1a). When \(\mu_{A}\) is larger than 3.0, \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) will always be 0.0 as the negative effects beyond the positive contributions from inter-layer and intra-layer parameters. Figure 6b presents the variation of TA with \(\mu_{A}\), in which an increase for TA is observed with the growth of \(\mu_{A}\) especially for a larger \(\mu_{A}\). It is the results of balance between contributions from different aspects.

Discussion on the influence of layers with unequal scale

In some conditions, the scales of two layers may not be equal. Then the inter-layer parameters \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) will not be same anymore. In this section, we investigate the influence of layers with unequal scale. Without loss of generality, the layer A is assumed to have a larger scale, which is two time that of the layer B. All the parameters are the same as Section “Influences of intra-layer parameters”, except that \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\) are 4 and 2 instead of 2 and 2 due to the scale difference. Similarly, a range of 2–30 is adopted for the parameters \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\).

To analyze the influence of layer scale quantitatively, we define the difference of \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\rho_{\infty }^{B}\) as \(\Delta \rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\Delta \rho_{\infty }^{B}\), which indicates \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\rho_{\infty }^{B}\) with the new inter-layer parameters minus that with the old ones. The variation of \(\Delta \rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\Delta \rho_{\infty }^{B}\) with different values of \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) are shown in Fig. 7. As shown in Fig. 7a, the influence of layer scale on \(\rho_{\infty }^{A}\) is limit. The value of \(\Delta \rho_{\infty }^{A}\) is smaller than 0.01 for all the cases and decays rapidly with the increase of \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\). A different phenomena is observed for \(\Delta \rho_{\infty }^{B}\), the value of which is up to larger than 0.07 for all the \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\). The results are reasonable as \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) is two times of \(\left\langle {k_{BA} } \right\rangle\), due to the difference of layer scale.

Figure 8 present the variation of \(\Delta T_{A}\) and \(\Delta T_{B}\) with different values of \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\). The definitions of \(\Delta T_{A}\) and \(\Delta T_{B}\) are similar to that of \(\Delta \rho_{\infty }^{A}\) and \(\Delta \rho_{\infty }^{B}\). Generally, the change of \(\left\langle {k_{AB} } \right\rangle\) result in the decrease of characteristic time. For the variation of \(\Delta T_{A}\) in Fig. 8a, the influence of layer scale is minimal except when the value of \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) is small (less than 6). For the variation of \(\Delta T_{B}\) in Fig. 8b, the influence is much more obvious. An obvious difference is observed even for a large \(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {k_{B} } \right\rangle\) (such as 10).

Conclusions

In this study, a comprehensive analysis of the SIS model on the two-layer interconnected networks is presented. By establishing a mathematical framework and employing computational methods, the research investigates the effects of various parameters on the steady-state infection proportion and the velocity of infection. Furthermore, the impact of unequal layer scales is also discussed. The paper obtains the following findings:

-

(1)

The intra-layer parameters significantly influence the infection dynamics. As the intra-layer parameters increase, the final Infection proportions in a layer will increase and the duration time for a layer to reach this state will decrease. Furthermore, taking layer A as an example, the intra-layer parameter of layer A (\(\left\langle {k_{A} } \right\rangle\)) has a larger effects than those of layer B on the infection dynamics of layer A, due to the direct and indirect effects of different parameters. The inter-layer parameters exhibit a similar performance as the intra-layer parameters.

-

(2)

A maximum value of 3.0 exists for the recovery-related parameters. This is the result of a balance between the positive contributions from the inter-layer and intra-layer infection processes and the negative contribution from the recovery process. When the negative effect of the recovery-related parameters outweighs the positive contributions from the infection-promoting parameters, the maximum value of the recovery-related parameters is reached.

-

(3)

When the scales of the two layers are unequal, the influence of intra-layer parameters will be more obvious for the layer with a smaller scale. This is because, for the layer with a smaller scale, changes in intra-layer parameters have a larger impact on the overall network structure and the connectivity of nodes. As a result, changes in the final Infection proportions and the time to reach the steady state are more pronounced compared to the layer with a larger scale.

This work can offer practical guidance for managing and controlling the spread of infection in real-world scenarios. The application of other epidemic models such as the SI or SIR models is also straightforward, as the main differences among the models are just the evolution equations (Eq. 1). However, limitations still exist for the present model. In the model, all simulations are based on the statistical average of the network rather than a node in the network. Therefore, it is impossible to judge the situation of a specific node. In the future, more elaborate complex network simulation methods will be used to achieve specific analysis of individuals.

Data availability

The data used to support this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pastor-Satorras, R., Castellano, C., Van Mieghem, P. & Vespignani, A. Epidemic processes in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 925–979 (2015).

Wang, W., Tang, M., Stanley, H. E. & Braunstein, L. A. Unification of theoretical approaches for epidemic spreading on complex networks. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 036603 (2017).

de Arruda, G. F., Petri, G. & Moreno, Y. Social contagion models on hypergraphs. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023032 (2020).

Gao, Z., Ghosh, D., Harrington, H. A., Restrepo, J. G. & Taylor, D. Dynamics on networks with higher-order interactions. Chaos 33, 040401 (2023).

Lücke, M., Winkelmann, S., Heitzig, J., Molkenthin, N. & Koltai, P. Learning interpretable collective variables for spreading processes on networks. Phys. Rev. E 109, L022301 (2024).

Nikolaou, M. Revisiting the standard for modeling the spread of infectious diseases. Sci. Rep-UK. 12, 7077 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Li, S., Zhang, J., Ma, J. & An, H. Traffic-driven SI epidemic spreading on scale-free networks. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 33, 2250111 (2022).

Zhao, X. et al. Effects of memory on spreading processes in non-Markovian temporal networks based on simplicial complex. Phys. A 606, 128073 (2022).

Li, K., Chen, Z., Cong, R., Zhang, J. & Wei, Z. Simulated dynamics of virus spreading on social networks with various topologies. Appl. Math. Comput. 470, 128580 (2024).

Kivelä, M. et al. Multilayer networks. J. Complex Netw. 2, 203–271 (2014).

Santoro, A. & Nicosia, V. Algorithmic complexity of multiplex networks. Physi. Rev. X 10, 021069 (2020).

Artime, O. et al. Multilayer Network Science: From Cells to Societies (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Raghav, T. & Jalan, S. Spacing ratio statistics of multiplex directed networks. New J. Phys. 25, 053012 (2023).

Liu, Y., Li, A., Zeng, A., Zhou, J. & Fan, Y. Motif-based community detection in heterogeneous multilayer networks. Sci. Rep.-UK 14, 8769 (2024).

Wei, X., Wu, X., Chen, S., Lu, J. & Chen, G. Cooperative epidemic spreading on a two-layered interconnected network. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 17, 1503–1520 (2018).

Bernal, J. R., Alarcón, R. L. A. & Schaum, A. Spreading control in two-layer multiplex networks. Entropy-switz 22, 1157 (2020).

Wang, Z., Xia, C., Chen, Z. & Chen, G. Epidemic propagation with positive and negative preventive information in multiplex networks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 51, 1454–1462 (2021).

Lin, X., Shang, Y. & Jiao, Q. Epidemic spreading over multi-layer networks with stubborn agents. IEEE T. Circuits-II 71, 812–816 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Coupled propagation dynamics on complex networks: A brief review. Europhys. Lett. 145(1), 11001. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/ad0f4f (2024).

Xiao, W., Li, M. & Chen, G. Small-world features of real-world networks. J. Commun. Netw. 19, 291–297 (2017).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of “small-world” networks. Nature 393, 440–442 (1998).

Wang, D. & Barabási, A. L. Understanding the spreading patterns of mobile phone viruses. Science 324, 1036–1039 (2016).

Onnela, J. P. et al. Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 7332–7336 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos: 72174045, 72174046) and the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (No: LH2021G013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y. Zhou and Y. Li; methodology: Y. Zhang; software: Y. Zhang; writing-original draft: Y. Zhou; writing-review and editing: Y. Li and Y. Zhang; funding acquisition, Y. Li.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Li, Y. & Zhang, Y. Numerical sensitivity analysis of the susceptible- infected- susceptible model on two-layer interconnected networks. Sci Rep 15, 9723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92320-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92320-1