Abstract

Lung cancer is a leading cause of mortality in oncological classifications, yet the impact of various risk factors on lung cancer mortality (LCM) in non-smokers remains unclear. This study aims to weigh out the diverse impact of multiple risk factors on LCM rates and identify trends in LCM rates worldwide. We initially employed Random Forest Tree (RFT) and Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) to identify common primary factors influencing LCM. After eliminating four common primary factors, a comparative analysis between partial and Pearson correlations was conducted to filter out significant factors in the correlations between risk factors and LCM rates across 204 countries from 2005 to 2019. The findings show that excluding the impacts of occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, occupational exposure to silica, occupational exposure to asbestos, high systolic blood pressure, secondhand smoke, child wasting, and alcohol use had a considerably greater impact on LCM than particular matter pollution (PM2.5). Furthermore, a Multiple Joinpoint Regression analysis identified increasing trends of LCM rates in the 142 countries (e.g., China and India); decreasing trends in 38 countries (e.g., Denmark and Norway), and stable trends in 24 countries (e.g., Sudan, Mali, and Australia). This research suggests that in addition to considering the effects of occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, and occupational exposure to silica on LCM rates, occupational exposure to asbestos, high systolic blood pressure, secondhand smoke, child wasting, and alcohol use should be considered in lung cancer prevention strategies, especially in countries with increasing trends of LCM rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer is a leading cause of mortality among cancer patients. It is characterized by a lack of specific early symptoms, and symptoms may not appear even in advanced stages, making early detection based on clinical signs difficult. By the time lung cancer is diagnosed, it is typically in stage IV, with a 5-year survival rate of just 22%1. When it was first identified in the 20th century, lung cancer was a rare malignancy that originated in the lungs2. However, it quickly became one of the major public health burdens in the U.S. According to the American Cancer Society, an estimated 350 people die from lung cancer each day in the U.S., exceeding the combined number of deaths from breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancers. Lung cancer causes 2.5 times more deaths than colon cancer. In 2022, there were 609,360 lung cancer deaths, and in 2023, over 238,000 new cases were diagnosed, with more than 127,000 deaths reported in the U.S. This de facto counted for the largest proportion death of cancer deaths3. Similarly, lung cancer in China had a higher mortality rate among the elderly than in other countries. It was the leading cancer death among cancer lineage. There were an estimated 0.87 million new cases and 0.766 million deaths in 20234.

According to data from the Genomic Data Commons Data Portal of the National Cancer Institute, lung cancer has an overall survival rate of less than 20%. 52.57% of lung cancer patients are female, and 69.72% of cases involve adenomas and adenocarcinomas (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). In light of cancer over time statistic of lung cancer mortality (LCM) in age [0–84] from 1992 to 2014 in International Agency for Research Cancer, existed age-standardized rate (ASR) of male steeply declined from 43.7 to 26.7 per 100,000 people while the rate for female almost stagnated during 12.5–12.9 per 100,000 people over the same period, owing to the tobacco control. The crude rate per 100,000 of male decreased from 53.3 to 46.4, while that rate for female increased from 18.9 to 25. The cumulative risk (in percentage) for men decreased from 10 to 7, while that for women fluctuated from 2.8 to 3.1 (https://gco.iarc.fr/overtime/en/dataviz/). Based on a 2020–2021 cancer report from IARC, lung cancer was responsible for about 2.2 million deaths worldwide, accounting for approximately 11.4% of cancer-related deaths.

The question of how to accurately assess the multifaceted impact of risk factors on LCM rates remains unresolved. While smoking is well-established as the dominant risk factor3,5,6, other factors such as occupational exposures7,8,9, environmental pollutants10,11,12, socioeconomic status13,14, and comorbidities15 have not been fully elucidated. Research has often relied on limited regional samples or focused on individual factors in isolation, leaving gaps in our understanding of the broader, multifaceted nature of lung cancer risk. Addressing these gaps are crucial, as the complex interplay of various factors may have a substantial impact on LCM. Clarifying these interconnections provided a more comprehensive understanding of how different risk factors contribute to LCM. In light of this, our research aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of lung cancer risk factors, assessing the broader effects on LCM rates, including indirect and previously overshadowed factors. We also investigate the spatio-temporal disparities in LCM globally, offering new insights into the complexity of risk factors beyond smoking.

Data and method

We collected data on LCM and mortality associated with 73 risk factors in 204 countries for the period 2005 to 2019 from open datasets published by the Global Burden of Disease (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/). The dataset contained 3060 observations. Mortality associated with a risk factor is simply the estimated number of deaths associated with each of the 73 risk factors. The 73 risk factors are listed in Table 1.

Investigation Procedure

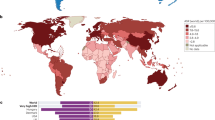

We conducted an analysis of LCM rates across 204 countries, as illustrated in Figure 1. The age-adjusted LCM rates were classified into five categories—very low risk, low risk, medium risk, high risk, and very high risk—based on a quintile classification.

First, Random Forest Tree (RFT) modeling and Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) were employed to identify four major common risk factors among the 73 factors analyzed.

Second, partial correlation and bivariate Pearson correlation analyses were performed on the remaining factors.

Third, we compared the coefficient differences between partial correlation and bivariate Pearson correlation to filter out significantly impactful variables related to LCM rates.

Fourth, a GBR model was developed for the selected variables.

Finally, a Multiple Joinpoint Regression model was employed to reveal trends in LCM rates worldwide. The analysis framework is depicted in Figure 2.

Analysis framework Note: Produced using Visio Microsoft https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/visio/flowchart-software (Accessed on October 16th 2024).

Partial correlation analysis

Partial Correlation is used to analyze the relationship between two continuous variables while accounting for the influence of control variables. In this analysis, four control variables were included: occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, and occupational exposure to silica. The analysis begins by checking whether the LCM rates meet normality assumptions. As shown in Fig. 3(a), the LCM rates distribution is skewed. Therefore, a logarithmic transformation was applied to normalize the distribution, as illustrated in Fig. 3(b). This method is particularly useful for uncovering spurious or hidden correlations that may not be initially apparent16.

Calculate the correlation coefficient r.

Where rXY is the coefficient of the relationship between X and Y.

rXZ is the coefficient of the relationship between X and Z.

rYZ is the coefficient of the relationship between Y and Z.

We made hypothesis below.

H0: 73 risk factors were not related with LCM rates after the impacts of occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, occupational exposure to silica.

H1: 73 risk factors were related with LCM after the impacts of occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, occupational exposure to silica.

Conduct t-test using the following.

where n is the sampling size, q refers to the order of partial correlations, t ~ Tdf = n-q-2.

calculate p-value and get the conclusion. If p value is less than 0.05, reject H0, meaning 73 risk factors were significantly related to LCM rates.

Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR)

The GBR is a machine learning approach that develops a predictive model by combining an ensemble of weak learners in a sequential order. The rationale of gradient boosting is to interactively optimize a loss function by adding weak models to ensemble. Each weak model is trained to correct the previous errors sequentially. This method improves prediction powers and creates a highly accurate and robust predictive model that can handle complex patterns and interaction in the data17. Due to flexibility, scalability, and interpretability characteristics, gradient boosting was widely used in epidemiology. The procedure is below.

Format \({f}_{0}\left(\chi \right).\)

Calculate negative gradient for m = 1 to M.

By minimizing Mean Squared Error (MSE), fit hm(x) into \({y}_{i}{\prime}\).

Use line search to identify learning rate \({\rho }_{m}\) to optimize a loss function L.

Output \({f}_{m}\left(x\right).\)

In Fig. 4, the top five risk factors associated with LCM were occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, occupational exposure to silica and childhood sexual abuse. Of note, after running 73 predisposing factors in the GBR model, occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, occupational exposure to silica four factors were common to the RFT. Therefore, these four factors were treated as control variables in this research.

Joinpoint regression

It is a common modeling in medical research and applied to find the years when mortality rate/incidence case/annual percent change occurred and trend prediction, proposed by Kim (2000)18,19,20,21,22. We implemented the Joinpoint regression in Joinpoint Regression Program 4.9.1.0 to estimate trends in LCM rates in a number of countries based on average annual percentage change (AAPC). We used age-adjusted rate of LCM as the dependent variable, particulate matter pollution as the standard error, uncorrelated as "choose an error model to fit". The independent variable was “year” and the interval type was “annual”. The minimum number of Joinpoints set up as 0 and maximum number was 2(i.e., the maximum number of the infliction point of the trend that can be accepted). The grid search option is selected under the Method settings window. The permutation test was defined with an overall significance level of 0.05 and the default number of permutations set to 4499. Annual Percent Change (APC)/AAPC confidence intervals are selected by parametric method.

Results

Results of RFT

According to the method in the published paper23, we performed the RFT. The top 5 risk factors associated with LCM were occupational exposure to arsenic, occupational exposure to silica, residential radon, smoking, and occupational exposure to nickel in Fig. 5.

Importance of different risk factors determined by the FRT. Note: Produced using google Colab (https://colab.research.google.com/, accessed on October 16th 2024).

Results of partial correlation

By eliminating the effects of common major factors, 70.59% of the variables’ correlation directions were changed. The correlation coefficients for 30 variables, initially positive, became small and negative in the partial correlations, indicating that the impact of these variables may be minimal and not associated with an increase in LCM rates. For example, the Pearson correlation coefficient for ambient ozone pollution, initially 0.342, changed to −0.118 in the partial correlation, suggesting that ambient ozone pollution is not related to an increase in LCM rates. Similarly, some dietary factors, such as a diet low in fruits and a diet low in fiber, also showed exhibited the same pattern.

Additionally, the correlation signs of 17 variables shifted from negative to positive, as shown in Table 2. This change suggests that the original correlations might have been influenced by four major factors. By controlling for these factors, partial correlation reveals the direct relationship between variables. The sign change also indicates a distinction between direct and indirect effects, where the initial correlation may have represented an indirect effect mediated by major factors. Once these major factors are controlled for, the direct effect becomes isolated and may show a different direction. However, their coefficients were lower than 0.1, indicating that their effects were extremely weak and could be disregarded. The coefficients for occupational exposure to asbestos and occupational carcinogens were approximately 0.5, indicating a moderate positive association with LCM.

Results of the selection of variables

We identified eleven significantly representative variables based on prior research findings, ensuring that the selected variables reflect diverse and impactful aspects pertinent to the research objective, as shown in Table 3.

First, alcohol consumption was found to be modestly associated with an increased risk of lung cancer in the pooled analysis. This link is primarily attributed to alcohol’s role in increasing oxidative stress or acting as a solvent for tobacco carcinogens24,25.Additionally, child stunting and wasting, which result from malnutrition during childhood, have been shown to negatively impact lung development and increase susceptibility to respiratory infections. This contributes to 45% of all deaths in children under five, equating to approximately 3.1 million deaths annually26,37.

Second, red meat consumption has been significantly associated with a greater risk of lung cancer (RR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.09–1.44). The risk is linked to high-temperature cooking processes that produce mutagenic heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and the heme iron content in red meat, which can catalyze the formation of N-nitroso compounds (NOCs)27. In contrast, a higher body mass index (BMI) appears to correlate with a reduced risk of lung cancer, likely due to confounding factors such as smoking-related weight loss and reverse causation, where preclinical lung cancer leads to lower body weight28.

Third, elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol has been implicated in lung cancer development. LDL can enhance cancer cell growth and metastasis by modulating membrane fluidity and signaling pathways29. Both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were identified as significant predictors of lung cancer, with a 10% increase in risk for every 10-mmHg increment in blood pressure. This is due to shared risk factors such as smoking and underlying metabolic abnormalities30.

Fourth, metabolic risks, including obesity, hypertension, and insulin resistance, have been linked to an increased risk of lung cancer31. Occupational exposure to asbestos is another significant factor, with studies indicating that asbestos-related lung cancer (ARLC) incidence is six times larger than mesothelioma incidence, marking it as a critical health concern32.

Fifth, particulate matter (PM) pollution, especially fine particles like PM2.5, has been established as a significant risk factor for lung cancer. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified outdoor air pollution and PM2.5 as carcinogenic to humans, affirming the clear link between PM exposure and lung cancer development33. Furthermore, a systematic review published in the European Journal of Public Healthestimated that ambient PM2.5 exposure contributes to a substantial burden of lung cancer cases globally, emphasizing the critical need for air quality interventions to reduce cancer risk34.

Lastly, secondhand smoke, a mixture of side stream and mainstream tobacco smoke, contains over 7,000 chemicals, including around 70 known carcinogens. Inhalation of this smoke increases the risk of lung cancer in nonsmokers by 20–30%, leading to over 7,300 lung cancer deaths annually among U.S. adults who do not smoke. The correlation between secondhand smoke and lung cancer is due to the toxic and carcinogenic substances present in the smoke, such as benzene, formaldehyde, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These findings are based on the National Academy Press (1986), which provided crucial insights into the harmful effects of secondhand smoke35.

Results of gradient boosting regression

Through Gradient Boosting Regressor with least squares loss and 500 regression trees of depth 4 in supplemental Fig. 1, the mean squared error (MSE) was 9.36 and R2 was 0.98. We set parameters including n_estimators of 500 (i.e., boosting stages were 500.), max_depth of 4 (i.e., the number of nodes in the tree is limited to 4.), min_samples_split of 5 (i.e., the minimum number of samples required to split an internal node was 5.), learning_rate of 0.01 (i.e., the contribution of each tree would shrink by 0.01.), loss of squared_error (i.e., the least squares function was used as the loss function to optimize.). In supplemental Fig. 2, deviance in training set and test set were close to 0 and dramatically decreased, which training set deviance was highly fit in test set deviance. The reason was that deviances, as the opposite of variance, were less and less, which meant the predicted regression was better and better. Supplemental Fig. 3 displayed permutation importance of 11 extracted risk factors determined by GBR. The significance of occupational exposure to asbestos, high systolic blood pressure, secondhand smoke, child wasting, ,alcohol use, child stunting, diet high in red meat, and high LDL cholesterol was found to be greater than that of particulate matter pollution (PM2.5).

Results of joinpoint regression

A multiple join-point regression analysis of LCM was conducted in 204 countries in Fig. 6, we merely presented a part of countries such as Australia, Brazil, Canda, China, Cuba, Denmark, Germany, and Japan, owing to the shared characteristics of trend homogeneity. During the study period, Canada, France, Japan, the U.S and etc. have a single infliction point, while China, Germany, Indonesia, Norway and etc. have two the infliction points in Table 4. Denmark ranked first in LCM rates while Sudan ranked last. LCM in China, Indonesia, Bermuda, and Japan was considered to have a significantly increasing trend due to the positive APC, whereas the LCM in Denmark was considered to have a significantly decreasing trend due to a negative APC in Table 5. Regarding the Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) in LCM rates, significant increasing trends were observed in 142 countries, including Bermuda, China, France, Indonesia, and Japan, as indicated by the positive AAPC values shown in Table 6. Conversely, LCM rates in 38 countries, such as Norway and Demark exhibited a decreasing trend, while 24 countries, including Sudan, Mali, and Australia demonstrated stable trends over the same period, as also outlined in Table 6.

Discussion

The analysis identified four major factors contributing to lung cancer: occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon exposure, and occupational exposure to silica. Additionally, the significance of occupational exposure to asbestos, high systolic blood pressure, secondhand smoke, child wasting, and alcohol use was found to be greater than that of particulate matter pollution (PM2.5). It does not mean PM2.5 less important. PM2.5, meaning 2.5 µm or smaller in diameter, has significant impacts on lung cancer due to its ability to penetrate deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream. PM2.5 was reported that it had high burden of acute respiratory infections (ARI) in children36. Among the countries studied, China, France, Indonesia, and Japan showed increasing trends in LCM rates, while Norway demonstrated a decreasing trend. These findings enhance our understanding of early prevention and holistic recognition of lung cancer at the country level. The insights provided by the proposed tree-based machine learning algorithm, in conjunction with partial correlation and multiple Joinpoint regression analysis, can be applied to other significant diseases to evaluate multifaceted factors that are closely related. Meanwhile, the research provided additional perspective into the GBD risk factors for interpreting fatal diseases of LCM rates. GBD is a global project involving more than 5,000 researchers from 154 countries and territories on 483 separate outcomes of 107 diseases and injuries and 14 million death certificates37,38,39,40.

First, The identification of occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, and occupational exposure to silica as four major common factors influencing LCM rates corroborates findings from prior lung cancer research. Generally speaking, arsenic, radon, and silica as toxic chemical elements do not directly affect humans but rather infiltrate and compromise health through the surrounding environment. They permeate outdoor air, indoor environments, everyday materials, drinking water, and other mediums, subtly encroaching on people’s well-being. Arsenic, is a carcinogenic chemical, involving long latency periods and indirect effects on human health. It typically through inhalation in industrial settings such as mining, smelting, and manufacturing, can lead to the toxic accumulation of arsenic in the lungs. Prolonged exposure can damage DNA and induce oxidative stress, ultimately increasing the risk of developing lung cancer. Irva et al. (1992) mentioned that the joint effects of both occupational exposure to arsenic and smoking increased the risk of lung cancer from 70 to 130%41. Radon is a radioactive gas that naturally arises from the decay of uranium found in soil, rock, and water. It can build up inside buildings, especially in basements and ground floors. Inhaling radon decay products can harm lung tissue, causing mutations and raising the risk of lung cancer. Radon concentrations also caused a significant risk of lung cancer8. Silica dust is produced in industries like construction, mining, and manufacturing. Breathing in fine silica particles can lead to silicosis, a lung disease characterized by scarring of lung tissue. This scarring creates conditions that promote the development of lung cancer by inducing chronic inflammation and increasing cellular damage. The relationship between occupational exposure to silica and lung cancer risk had a positive exposure–response relationship42. Of note, the identification of smoking as one of the main risk factors highlights the credibility of our methodology, as it aligns with the findings of most existing lung cancer studies.

Second, our analysis revealed that poccupational exposure to asbestos, high systolic blood pressure, secondhand smoke, child wasting, and alcohol use were the top five variables that had a greater impact on LCM rates than environmental factors, with the exception of the four common risk factors, among the 73 factors evaluated using Gradient Boosting Regression. Some literatures mentioned occupational exposure to asbestos, High systolic blood pressure, Secondhand smoke, Child wasting, and Alcohol use exacerbated the risk of lung cancer43,44,45,46,47. Asbestos refers to fibrous minerals, which used to resist either heat or corrosion. When asbestos fibers are absorbed, they can be stored in the lungs, resulting in inflammation and scarring to form asbestosis, which is a chronic lung disease, increasing the risk of lung cancer. Asbestosis in asbestos-exposed lung cancer account for more than in the nonexposed lung cancer7. High systolic blood pressure is generally associated with cardiovascular diseases, recent studies suggest a potential link to lung cancer. Cho et al. (2021) mentioned high systolic blood pressure was linked increased risk of lung cancer48. Secondhand smoke contains benzene, formaldehyde, and nitrosamines carcinogens. Regular exposure for non-smokers to secondhand smoke can do harmful lung tissue, causing mutations that enhance the risk of lung cancer. Some research mentioned secondhand smoke had the most detrimental effects for children49,50. Child wasting revealed the importance of nutrition for LCM, which was confirmed by Ilaria et al. (2020)51. Alcohol use does attack and weaken individual’s immune system, making the body less capable of fighting off cancerous alteration in the lungs and other organs. Some existed research also mentioned alcohol consumptions was pertinent to lung cancer onset in never-smokers52,53,54.

Next, Multiple Joinpoint regression not only summarized the year-to-year variations in LCM rates with different trends across all countries but also provided a valuable tool for comparing disparities between these units during the study period19. To maximize the utility of the investigation, we selected 204 countries for analysis. The findings indicate that LCM rates showed increasing trends in 142 countries. These countries are often highly populated, such as China, India, and Indonesia, and span various climates-from tropical regions like Indonesia and Brazil to temperate zones like Finland and Sweden, and even desert areas such as Saudi Arabia and Namibia. These regions often face health challenges due to limited distribution of health resources. Those countries should pay more attention to improve health system and LCM rates prevention. Conversely, LCM rates exhibited decreasing trends in 38 countries, which are typically developed nations facing different public health challenges. Meanwhile, 24 countries showed stable LCM trends, suggesting that nations with more advanced healthcare systems tend to achieve better health outcomes, whereas those with weaker systems may struggle with higher LCM rates. Additionally, this study focused on analyzing longitudinal trends in LCM rates for vertical comparisons and examined the potential impact of predisposing factors through horizontal contrasts. This approach aims to enhance the understanding of early prevention and control of lung cancer at the national level.

Lastly, our analysis has several limitations. Firstly, the GBD data were large scale, aggregated at the country level, encompassing a vast array of exposure estimates that caused the inconsistency between localized findings and global assessments should be addressed in future research. For instance, Smith et al. (2018) reported an increase in LCM associated with arsenic exposure (relative risk [RR] of 3.38) in regions of Chile, focusing on the long-term impact of arsenic exposure on LCM using limited datasets55. Nevertheless, Leiter et al. (2023) identified smoking as the leading risk factor for lung cancer56,57. In our analysis, the risk associated with smoking appears lower than that of arsenic exposure. This discrepancy may stem, in part, from differences in study scale, data sources, and the limitations of machine learning methods, which may not fully account for discrepancies in measurement units. Addressing this discrepancy, we should further detail how occupational arsenic exposure was measured and whether the statistical model adjusted appropriately for confounders. Moreover, LCM research should further consider demographic factors such as gender, age, and racial differences across different countries. However, current lung cancer research predominantly focuses on macro-level analyses of country heterogeneity, rather than addressing and targeting the core aspects of lung cancer therapy. Furthermore, LCM should be categorized into non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) for a more nuanced discussion, given that NSCLC and SCLC account for 85% and 15% of lung cancer cases, respectively14,58,59. Finally, this study may have a temporal disconnect between the exposure to certain risk factors and the observed lung cancer outcomes. Specifically, the latency period for asbestos-related lung cancer is typically 20–40 years. This means that exposure to asbestos in earlier decades, such as the 1960s-1980s, would most likely be responsible for the LCM observed in the 2004–2020 period. Therefore, it is important to recognize that the lung cancer outcomes in this study reflect past exposures rather than current or recent risk factor levels.

Conclusion

Lung cancer is an enteral academic spotlight, unless cancer is no longer a threat to humanity. How to mitigate LCM is still a challenge. Our study utilized machine learning algorithms to identify four common major risk factors (i.e., occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, occupational exposure to silica) and high impactful risk factors (i.e., Occupational exposure to asbestos, High systolic blood pressure, Secondhand smoke, Child wasting, and Alcohol use), as well as Multiple Joinpoint Regression to identify increasing trends of LCM rates in 142 countries (e.g., China and India); decreasing trends in 38 countries (e.g., Denmark and Norway), and stable trends in 24 countries (e.g., Sudan, Mali, and Australia). This research suggests that in addition to considering the effects of occupational exposure to arsenic, smoking, residential radon, and occupational exposure to silica on LCM rates, occupational exposure to asbestos, high systolic blood pressure, secondhand smoke, child wasting, and alcohol use should be considered in lung cancer prevention strategies in countries with increasing trends of LCM rates. Future research should focus on determining the impact of these risk factors on LCM rates at mesoscale and fine scale.

Data availability

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article.

References

Choi, E. et al. Risk model-based management for second primary lung cancer among lung cancer survivors through a validated risk prediction model. Cancer 130(5), 770–780. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.35069 (2024).

Molassiotis, A., Kwok, S. W. H., Leung, A. Y. M. & Tyrovolas, S. Associations between sociodemographic factors, health spending, disease burden, and life expectancy of older adults (70 + years old) in 22 countries in the Western Pacific Region, 1995–2019: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019. GeroScience 44(2), 925–951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-021-00494-z (2022).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Fuchs, H. E. Cancer statistics. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 72(1), 7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.217 (2022).

Ju, W. et al. Cancer statistics in Chinese older people : current burden, time trends, and comparisons with the US, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Sci. China Life Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-022-2218-x (2022).

Samet, J. M. Carcinogenesis and lung cancer: 70 years of progress and more to come. Carcinogenesis. 41(10), 1309–1317. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgaa094 (2020).

Omenn, G. S. et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 334(18), 1150–1155 (1996).

Icksan, A. G., Widharisastra, C., Suraya, A., & Ferstl, M. Pleural plaques and pleural changes among lung cancer patients exposed to asbestos. Universa Medicina 41 3 210–218 https://doi-org.libproxy.txstate.edu/https://univmed.org/ejurnal/index.php/medicina/article/view/1307/712 (2022)

Alavanja, M. C. R., Lubin, J. H., Mahaffey, J. A. & Brownson, R. C. Residential radon exposure and risk of lung cancer in missouri. Am. J. Public Health 89(7), 1042–1048. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.89.7.1042 (1999).

Jones, R. N., Hughes, J. M. & Weill, H. Asbestos exposure, asbestosis, and asbestos-attributable lung cancer. Thorax 51(suppl 2), S9–S12 (1996).

Luo, R. X., Wu, B., Yi, Y. N., Huang, Z. W. & Lin, R. T. Indoor burning coal air pollution and lung cancer—a case-control study in Fuzhou. China. Lung Cancer 14(suppl 1), S113–S119 (1996).

Elizabeth, G. New evidence that air pollution contributes substantially to lung cancer. The Lancet Oncol. 23(10), e448. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00569-1 (2022).

Pope, C. A. et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 287(9), 1132–1141 (2002).

Bray, F. I. & Weiderpass, E. Lung cancer mortality trends in 36 European countries: secular trends and birth cohort patterns by sex and region 1970–2007. Int. J. Cancer 126(6), 1454–1466. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.24855 (2010).

Gongbo, C., Xia, W., Gonghuan, Y. & Xiaonong, Z. Traffic-related air pollution and lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Thorac. Cancer 6, 307–318 (2015).

Zeng, X., Zhu, S., Xu, C., Wang, Z., Su, X., Zeng, D., Long, H., & Zhu, B. (2020). Effect of Comorbidity on Outcomes of Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Undergoing Anti-PD1 Immunotherapy Medical Science Monitor https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.922576.

Jinting Zhang, F., Zhan, B., Xiu, Wu. & Zhang, D. Partial correlation analysis of association between subjective well-being and ecological footprint. Sustainability. 13(3), 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031033 (2021).

Luo, J., Wei, Z., Man, J. & Xu, S. TRBoost: a generic gradient boosting machine based on trust-region method. Appl. Intell.: Int. J. Res. Intell. Syst. Real Life Complex Probl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-023-05000-w (2023).

Dragomirescu, I. et al. A join point regression analysis of trends in mortality due to osteoporosis in Spain. Sci. Rep. 9, 4264. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40806-0 (2019).

Akinyede, O. & Soyemi, K. Joinpoint regression analysis of pertussis crude incidence rates, Illinois, 1990–2014. Am. J. infect. control. 44(12), 1732–1733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.013 (2016).

Kim, H. J., Fay, M. P., Feuer, E. J. & Midthune, D. N. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat. Med. 19(3), 335–351 (2000).

Huang, J. et al. Incidence and mortality of thyroid cancer in 50 countries: A joinpoint regression analysis of global trends. Endocrine: : Int. J. Basic & Clin. Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-022-03274-7 (2023).

Politis, M. et al. Trend analysis of cancer mortality and incidence in Panama Using Joinpoint Regression Analysis. Medicine 94(24), e970. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000970 (2015).

Wu, X., Denise, B.-B., Zhan, F. B. & Zhang, J. Determining association between lung cancer mortality worldwide and risk factors using fuzzy inference modeling and random forest modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. & public health. 19, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114161 (2022).

Freudenheim, J. L. et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of lung cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 82(3), 657–667. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/82.3.657 (2005).

Bagnardi, V. et al. Alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk in never smokers: a meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 22(12), 2631–2639. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr027 (2011).

Tharumakunarajah, R., Lee, A., Hawcutt, D. B., Harman, N. L. & Sinha, I. P. The impact of malnutrition on the developing lung and long-term lung health: A narrative review of global literature. Pulm. Ther. 10(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-024-00257-z (2024).

Farvid, M. S. et al. Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 36(9), 937–951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00741-9 (2021).

Robien, K. & DiPietro, L. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and lung cancer prevention. Chest 165(1), 14–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2023.10.044 (2024).

Kuzu, O. F., Noory, M. A. & Robertson, G. P. The Role of cholesterol in cancer. Cancer Res. (Chicago, Ill.) 76(8), 2063–2070. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2613 (2016).

Lindgren, A., Pukkala, E., Nissinen, A. & Tuomilehto, J. Blood pressure, smoking, and the incidence of lung cancer in hypertensive men in North Karelia Finland. Am. J. Epidemiol. 158(5), 442–447. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwg179 (2003).

Lee, Y.-Y. et al. Association between risk factors of metabolic syndrome with lung function. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 74(5), 811–817. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0369-6 (2020).

van Zandwijk, N., Frank, A. L., Reid, G., Dimitri Røe, O. & Amos, C. I. Asbestos-related lung cancer: An underappreciated oncological issue. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 194, 107861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.107861 (2024).

Berg, C. D. et al. Air pollution and lung cancer: A review by international association for the study of lung cancer early detection and screening committee. J. Thorac. Oncol. 18(10), 1277–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2023.05.024 (2023).

Corda, M. et al. The burden of lung cancer attributable to ambient PM2.5 exposure: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Public Health https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckae144.1418zs (2024).

Environmental tobacco smoke : Measuring exposures and assessing health effects (1st ed.) (National Academy Press, 1986)

Adhikary, M., Mal, P. & Saikia, N. Exploring the link between particulate matter pollution and acute respiratory infection risk in children using generalized estimating equations analysis: a robust statistical approach. Environ. Health: A Global Access Sci. Source 23(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-024-01049-3 (2024).

Murray, C. J. L. et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet 396(10258), 1223–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 (2020).

Solmi, M. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia - data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019. Mol. Psychiatr. 28(12), 5319–5327 (2023).

Ortblad, K. F., Lozano, R. & Murray, C. J. The burden of HIV: insights from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2010. The Lancet (British Edition) 381(S2), S103–S103. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61357-4 (2013).

Nichols, E., Wang, C. & Vos, T. P1–540: Multidimensional Item Response Theory (IRT) For survey harmonization and dementia prevalence prediction in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study: An example using the Health And Retirement An Retirement Survey (HRS). Alzheimer’s & Dement. 15(7S_Part_9), P478–P478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.1145 (2019).

Irva, H., Kauppinen, T., Pukkala, E. & Karjalainen, S. Cancer risk among workers exposed to arsenic and other inorganic compounds in the glass manufacturing industry. Scand. J. Work Environ. & Health. 18(2), 74–82 (1992).

Poinen-Rughooputh, S., Rughooputh, M. S., Guo, Y., Rong, Y. & Chen, W. Occupational exposure to silica dust and risk of lung cancer: an updated meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. BMC Public Health 16(1), 1137–1217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3791-5 (2016).

Emilie, R. et al. Asbestos exposure and the risk of lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 126(4), 047002. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP2735 (2018).

Lévêque, E. et al. Time-dependent effect of intensity of smoking and of occupational exposure to asbestos on the risk of lung cancer : results from the ICARE case–control study. Occup. & Environ. Med. 75(8), 586–592 (2018).

Lindgren, A., Holmquist, C. & Jansson, B. Hypertension and the risk of lung cancer in men: A prospective cohort study. J. Hypertens. 21(9), 1633–1638. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200309000-00013 (2003).

Štěpánek, L., Ulčák, Z. & Konečný, D. The impact of secondhand smoke exposure on lung cancer mortality in non-smokers: Evidence from the Czech Republic. Central Eur. J. Public Health. 30(3), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a6322 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Alcohol use and lung cancer risk: A large-scale cohort study in Chinese populations. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. & Prev. 32(7), 945–952. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-1129 (2023).

Cho, I., Han, K., Shin, D., Cho, M., Yoo, J., & Cho, J. Associations of variability in metabolic parameters with lung cancer: a nationwide population-based study Cancers, 13 8 https://doi-org.libproxy.txstate.edu/https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/13/8/1982. (2021)

Mbulo, L. et al. Secondhand smoke exposure at home among one billion children in 21 countries: Findings from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS). Tob. Control 25, e95–e100 (2016).

Nadhiroh, S. R., Djokosujono, K. & Utari, D. M. The association between secondhand smoke exposure and growth outcomes of children: A systematic literature review. Tob. Induc. Dis. 18, 12 (2020).

Ilaria, P. et al. Nutritional status and its role in lung cancer mortality: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Nutr. & Cancer. 72(3), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2020.1723729 (2020).

García Lavandeira, M. et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of lung cancer in never smokers: The SUN cohort study. Eur. J. Public Health. 28(4), 636–642. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky043 (2018).

García Lavandeira, J. A. et al. Alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk in never smokers: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Eur. J. Public Health 28(3), 521–527. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx196 (2018).

Bandera, E. V. et al. Alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk in the New York State cohort: A focus on never smokers and moderate drinkers. Cancer Causes & Control. 12(10), 931–939. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012205215302 (2001).

Smith, A. H. et al. Lung, Bladder, and Kidney Cancer Mortality 40 Years After Arsenic Exposure Reduction. JNCI : J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110(3), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx201 (2018).

Leiter, A., Veluswamy, R. R. & Wisnivesky, J. P. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20(9), 624–639. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3 (2023).

Wei, W. et al. Arsenic exposure and its joint effects with cigarette smoking and physical exercise on lung function impairment: Evidence from an occupational cohort study. Environ. Res. 196, 110419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110419 (2021).

Oser, M. G., Niederst, M. J., Sequist, L. V. & Engelman, J. A. Transformation from non-small-cell lung cancer to small-cell lung cancer: molecular drivers and cells of origin. Lancet Oncol. 16(4), e165–e172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71180-5 (2015).

Abdik, H. Antineoplastic effects of erufosine on small cell and non-small cell lung cancer cells through induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49(4), 2963–2971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-022-07117-6 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and comments.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript. Conceptualization and methodology, X.W., and J.Z.; investigation, resources, and data curation, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing, reviewing, and editing, and J.Z; supervision, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Zhang, J. & Yoshida, Y. Disentangling the effects of various risk factors and trends in lung cancer mortality. Sci Rep 15, 8719 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92373-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92373-2