Abstract

The fluorescent vesicles based on lanthanide ions are considered as an ideal biomimetic optical nanoplatform for simulating biological processes of cell membrane. However, the accurately and controllably adjusting the size of vesicles based on lanthanides while ensuring their fluorescence performance and stability still remains a challenge. Herein, a dual-stimuli-responsive fluorescent supramolecular vesicle with tunable size has been designed based on host-guest interaction and coordinating aggregation. Europium complexes can be encapsulated within supramolecular assemblies by assembling with polypseudorotaxanes (PPRs), which are formed by F127 and carboxymethyl-β-cyclodextrin (CMCD) through host-guest interaction. The fluorescence properties of the europium complexes have been significantly enhanced by confining and shielding them within vesicles. Upon the addition of α-amylase and HCl, the fluorescence intensity of the vesicles will gradually and significantly quench as a result of CMCD degradation and dissociation of the europium complexes. This research presents a convenient method for regulating the size of lanthanide fluorescent vesicles, and the supramolecular vesicles obtained with multi-stimuli response are anticipated to be utilized in the diagnosis of relevant diseases and targeted drug delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lanthanide ions are known for their intriguing photophysical properties, such as long-lived excited states, high quantum yield, large Stokes shifts, and sharp emission bands, rendering them optimal choices for the development of fluorescent materials1,2. However, the emission of the lanthanide ions can be easily quenched by the high frequency oscillators of solvent molecules present in their coordination sphere. Additionally, the poor processability, limited stability, and low mechanical strength of pure lanthanide complexes also have severely hampered their practical applications3,4,5. In recent decades, researchers have dedicated to exploring suitable matrices for lanthanides to overcome the aforementioned limitations.

Supramolecular aggregates, which are non-covalent assemblies formed by the reversible intermolecular forces such as hydrophobic effect, π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interaction and host-guest interaction, have been proposed as preferred matrices for overcoming the shortcomings of lanthanides6. The lanthanide ions or complexes could be confined in these organized assemblies in a noncovalent way, leading to enhanced fluorescence efficiency and photostability by reducing nonradiative vibrational deactivation and shielding solvent molecules7,8,9. On the other hand, their optical properties and morphology could be hierarchically controlled through rational design and adjustment of assemble units, which makes them highly desirable for special functional materials such as shape-memory, self-healing and information encryption10,11,12.

Within the diverse array of supramolecular aggregate topologies, vesicles have garnered significant attention due to their distinctive bilayer structure, which resembles that of the cell membrane, along with an internal solvent pool possing a substantial carrying capacity13. A series of lanthanide-based supramolecular vesicles with fluorescence-emitting properties have been developed and are currently regarded as a highly promising biomimetic nanoplatform for a multitude of applications. These include in-situ fluorescence tracking14,15, the expression of molecular information16,17 and the visualization of drug delivery18,19,20. For instance, luminescent vesicles assembled from europium complexes have been effectively utilized to monitor the conversion process between citrate and isocitrate14, as well as the molecular recognition of metal ions15. Luminescent vesicles fabricated by the amphiphilic Tb3+ complex exhibited a sigmoidal increase in luminescence intensity upon nucleotide binding, thereby enabling the conversion and amplification of molecular information16,17. Modified vesicles composed of lipid bilayers containing Eu3+ or Tb3+can serve as luminescent indicators for monitoring the enzymatic conversions19 and the permeation behavior of drugs20. By modulating the concentration of the amphiphilic lanthanide assembly unit or varying the solvent type, it becomes feasible to adjust the size and structure of the vesicles. Nevertheless, it is important to note that such modifications might give rise to potential quenching effects resulting from self-aggregation and solvents. Consequently, devising an optimal strategy for regulating the size of fluorescent supramolecular vesicles based on lanthanides persists as a formidable and challenging task.

Recently, cyclodextrins (CDs) have emerged as highly favorable dynamic building blocks in the realm of supramolecular aggregates21. They belong to a family of cyclic oligosaccharides containing a macrocyclic ring structure formed by six to eight glucose units, which is known as α-, β-, and γ-CD, respectively. The unique molecular structure of CDs, characterized by a hollow cage with a hydrophilic outer surface and a hydrophobic inner cavity, enables the favorable inclusion of hydrophobic parts of guest molecules endows them with the remarkable ability to favorably encapsulate the hydrophobic moieties of guest molecules, predominantly amphiphiles, through host-guest interactions22. Under the synergistic influence of CDs, the aggregation behavior of amphiphilic molecules undergoes a substantial transformation. Not only can they be further assembled into more complex higher-order structures with pronounced alterations in size and shape, but they also hold great promise for the fabrication of intelligent molecular devices endowed with stimulus-response characteristics23,24,25,26,27,28. By exploiting the assembly features of CDs, researchers endeavored to employ them as fundamental building blocks for fabricating fluorescence materials possessing customized optical and structural attributes, such as nanomaterials29.30, films31, and hydrogels32. These materials have been developed to be applied in multicolor imaging29,31, biosensing30 and smart lighting devices32. Therefore, the exploitation of host-guest interactions mediated by CDs is anticipated to facilitate the size modulation of fluorescent vesicles. However, to the best of our knowledge and a comprehensive review of the existing literature, the construction of lanthanide-based fluorescent supramolecular vesicles regulated by CDs has yet to be reported.

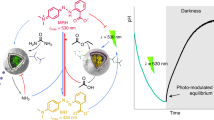

Herein, a fluorescent supramolecular vesicle with adjustable properties has been successfully developed via the cooperative assembly of europium complexes sensitized by 2,6-Pyridinedicarboxylic acid (DPA) and CD-based polypseudorotaxanes (PPRs). The guest molecule within the PPRs is the Pluronic copolymer F127, which is widely acknowledged as an idea nanocarrier for the loading and controlled release of anti-cancer drugs33. A commercially available carboxyl-substituted cyclodextrin, namely carboxymethyl-β-cyclodextrin (abbreviated as CMCD), was employed as the host molecule in the PPRs to establish a connection with the europium complexes. The host-guest (H/G) ratio of the PPRs can be altered by adjusting the concentration of F127, thereby inducing variations in both the size and fluorescence intensity of the supramolecular vesicles. Upon the addition of α-amylase and HCl, the emission intensity of the supramolecular vesicles could be quenched as the disassembly of the vesicles. The proposed design concept and facile strategy for regulating the size of the vesicle have offered a new avenue for the preparation of fluorescent vesicles. Moreover, their ability responsiveness to external stimuli renders them highly promising candidates for further exploration and development in the field of biomedical research and drug delivery.

Materials and methods

Materials

EuCl3·6H2O (99.9%), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES, 99.5%), and 2,6-Pyridinedicarboxylic acid (DPA, 99%) were purchased from Macklin Company (Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd, China) and used as received. Carboxymethyl-β-cyclodextrin sodium salt (CMCD, DS ~ 1.2), Pluronic triblock copolymer F127 (PEO100PPO64PEO100, Mw 12600) and α-amylase from Aspergillus oryzae (30 U/mg) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company. The average degree of substitution of CMCD have been revised by 1H NMR. All materials were purchased from commercial resources and directly used without further purification.

Sample preparation

Concentrated solutions of EuCl3, CMCD and DPA were first prepared by dissolving the desired amount of complexes in HEPSE buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4). An aqueous solution of 10 mM europium complex, [Eu(DPA)2]− (abbreviated as Eu[III]), was prepared by mixing the solutions of 2.0 mL EuCl3 (50 mM, 1 eq.) and 8.0 mL DPA (25 mM, 2 eq.). Then, the mixture was stirred for 2 h at 50 °C. By fluorescence titration, the optimum ratio of CMCD to Eu[III] was found to be 3. Then, a series of PPRs with different H/G ratios were synthesized with CMCD as the host (H) and F127 as the guest (G) at a fixed CMCD concentration. The determination of the host-guest ratio is based on two aspects: First, the hydrophobicity and steric fitting of the β-CD cavity make the PPO blocks of F127 more suitable for encapsulation than the PEO blocks. In addition, the height of a CMCD molecule was estimated to be 1.153 nm from the computer simulations (Fig. S1), and the extended PPO length of F127 is 23 nm (64 units) in its free energy minimized conformation34. Therefore, it was assumed that one F127 molecule could be potentially encapsulated by a maximum of 20 CMCD molecules when the PPO block was completely covered. Secondly, to ensure that the polymer chains of F127 were in the monomeric state before the formation of PPRs, the concentration of F127 was kept below its critical micellization concentration (CMC, 0.40 mM in buffer of pH 7.4 at 25 oC)35. Therefore, PPRs with H/G ratios ranging from 8 to 20 were prepared here by mixing different volumes of 7.5 mM F127 and 1.5 mL of 10 mM CMCD solutions. The volume of the solution was then replenished to 4.5 mL with 10 mM HEPES buffer. After ultrasonic treatment for 12 h at 40 °C and stabilization for 24 h at 25 °C, 0.5 mL of 10 mM Eu[III] was added dropwise to the prepared PPRs with stirring. The aggregates were finally obtained by further sonication for 24 h at 40 °C.

For the experiments on the enzymatic response to stimulation, 12.5 µL of concentrated α-amylase solution (8000 U/mL) was added to 1 mL of the aggregated systems. In the presence of 100 U/mL α-amylase at 37 °C, the dissociation of the aggregates was monitored over time by fluorescence emission spectroscopy.

The pH of the system was adjusted by adding trace amounts of HCl aqueous solutions. To maintain consistency in fluorescence, equal volumes of HCl at different concentrations were used here. The actual pH value was determined by a pH meter.

Characterization

The fluorescence spectra were recorded on the Edinburgh Instruments FLS920 luminescence spectrometer equipped with a 450 W xenon lamp. The luminescence lifetime was determined by using a µF920 microsecond flash lamp as an excitation source. The enzymatic and pH-stimulated response experiments were carried out on a RF-5301 PC Shimadzu spectrofluorometer, equipped with a 150 W xenon lamp. The data of dynamic light scattering (DLS) were monitored by a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS90 instrument. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were taken by a JEM-2100Plus equipped with the energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer operating at 200 kV. For the preparation of specimens for TEM analysis, a drop of sample was deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid and excess water was removed by filter paper. Since the presence of the electron-rich europium complex within the aggregate, which was sufficient to generate the necessary contrast, no additional staining agents were introduced here. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were taken on a JSM-6700 F SEM system. The specimen for SEM was first air-dried on a silicon wafer and then coated with a thin layer of gold prior to the examination process. The atomic force microscope (AFM) measurement was conducted by using a Bruker Dimension Icon in tapping mode under ambient conditions. Owing to the overlapping and covering of the aggregates during the testing process, the samples were initially diluted to a suitable concentration and subsequently coated onto clean silicon wafers. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) 1D and 2D 1H–1H ROESY measurements were performed on a Bruker Plus 600 MHz spectrometer in D2O.

Results and discussion

Fluorescence study

Although CMCD can be coordinated to Eu3+ via the carboxyl group, its fluorescence emission remains insignificant due to the lack of an energy transfer effect between CMCD and Eu3+. In order to attain the desired level of fluorescence intensity, the DPA ligand was chosen here to sensitize Eu3+. Meanwhile, it has been reported that the coordination sphere of Eu3+ can be essentially saturated by three DPA ligands36. To ensure an adequate number of coordination sites for the host molecule (CMCD), europium complexes coordinated with two DPA ligands, [Eu(DPA)2]− (abbreviated as Eu[III]), were employed here to fabricate supramolecular aggregates. As illustrated in Fig. S2, the fluorescence intensity of Eu[III] steadily increased with the an increasing molar ratio of CMCD, and then reached a maximum at the Eu[III]/CMCD molar ratio of 1:3. Any ratio exceeding this value will result in a reduction in fluorescence intensity, which can be ascribed to the competitive substitution of DPA ligands by CMCD molecules. Therefore, the fluorescence properties of europium complexes coordinated to CMCD (Eu[III]@CMCD) or to CMCD-based PPRs (Eu[III]@PPRs) have been investigated at a Eu[[III]/CMCD molar ratio of 1:3.

Figure 1 presents the emission spectra of Eu[III] after the addition of CMCD and PPRs, which are composed of CMCD and F127 with different H/G ratios (H/G = 8, 12, 16, and 20). Groups of narrow lines were identified as the characteristic 5D0 → 7FJ transitions of Eu3+37. Upon the addition of CMCD and CMCD-based PPRs, a remarkable increase in fluorescence intensity could be observed. Compared with the Eu[III]@CMCD, the fluorescence intensity of the Eu[III]@PPRs was enhanced by a factor of 5.2 when the H/G ratio of PPRs was 8. Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity of Eu[III] remained unchanged after adding the same concentration of F127 (Fig. S2c). This eliminates the possibility of any fluorescence variation that might be caused by the addition of F127. It thereby implies that a more favorable coordination environment could be provided for the central europium ions by the involvement of CMCD via the synergistic effect of PPRs.

Differences in the relative intensities of the emission bands also reflected the changes in the coordination environment after the addition of PPRs. As is well-established, the magnetic dipole transition from 5D0 → 7F1 at 594 nm is not affected by the chemical environment of surrounding the europium ion38. However, the intensity of electric-dipole transition from 5D0 → 7F2 is closely related to the site symmetry of central europium ion. Therefore, the variation of the microchemical environment around the europium ions can be quantified by evaluating the integrated transition intensity ratio of 5D0 → 7F2 to 5D0 → 7F1, which is usually denoted as η. The degree of symmetry in the coordination environment of europium ions is commonly determined by this ratio. A higher η value suggests a less symmetric coordination environment and improved fluorescence monochromaticity of the europium complex39,40. As listed in Table 1, the η value of Eu3+ increased from 2.56 to 3.81 (Eu[III]@CMCD) due to the coordination of the CMCD. Meanwhile, the calculated η values for europium complexes restricted within PPRs were all relatively higher than of that without PPRs (3.81), and the η values increased as the H/G ratio decreased. This implies that the interaction between Eu[III] and coordinated CMCD has been enhanced in the presence of PPRs, resulting in a more asymmetric crystal field for Eu3+41,42.

To further investigate this structural difference of the europium complexes, the luminescence lifetimes of Eu[III] in different situations have been measured (Fig. S3a), with the fitting results listed in Table 1. A biexponential lifetime was obtained from the decay curve for the sample of Eu[III]@CMCD (0.311 ms and 1.440 ms). The relatively short lifetime (0.311 ms) obtained here is consistent with the lifetime of [Eu(DPA)2]– reported by Horrocks et al.43. This suggests that only part of the coordination sites of the europium complex are coordinated by CMCD, while the rest of the site remains occupied by water molecules. Instead, the decay curves for other samples of Eu[III]@PPRs could all be well fitted to a single exponential function, indicating a uniform coordination environment exists in the europium complex due to the coordination by PPRs. In addition, the decay times obtained from Eu[III]@PPRs were found to be longer than that of Eu[III] and Eu[III]@CMCD. According to the luminescence lifetimes and emission spectra, the key physical parameter for the luminescence properties of the europium complexes could be determined (see Supplementary Information). As summarized in Table 1, there was a slight increase in radiative rate constant (kr) of Eu[III] after coordination with CMCD, specifically from 0.280 ms−1 to 0.344 ms−1. However, the non-radiative rate constant (knr) of Eu[III] exhibited a substantial reduction, decreasing from 2.998 ms−1 to 0.477 ms−1. This significant decrease in knr directly led to a corresponding remarkable increase in the quantum efficiency of Eu[III] (φ), which rose from 8.5% to 47.8%. This notable change suggests that CMCD plays a crucial role in reducing the nonradiative vibrational deactivation of the europium complex. This effect is not only preserved but also further enhanced within the Eu[III]@PPRs system. The relatively higher kr values and lower knr values were achieved for the europium complexes coordinated with CMCD via PPRs. Furthermore, the φ values found for Eu[III]@PPRs gradually increased with increasing H/G ratio, and all of them were higher than that of Eu[III]@CMCD. This indicates an enhanced luminescence efficiency of the europium complexes and an effective suppression of nonradiative decay by PPRs, which is most likely caused by replacing the coordinated water molecules (i.e., O-H oscillators) present in the coordination sphere of the europium ions39,44.

Along with the luminescence lifetime recorded by the control experiments in deuterium oxide (D2O), the average number of water molecules coordinating to one europium ion, q, could be calculated (Fig. S3b). Since there exists 9–10 coordinated water molecules in the coordination sphere of Eu3+ and three coordinated water molecules can be replaced by a tridentate DPA ligand, the q value in [Eu(DPA)2]− is except to be approximately 343. It is worth noting that the q value of Eu[III] was reduced to 0.43 after coordination with CMCD, and this value was further reduced in the presence of PPRs. As the H/G ratio decreased from 20 to 8, the number of coordinated water molecules in the first coordination sphere of Eu3+ reduced from 0.08 to 0.03. This suggests that more sufficient coordination of the europium complexes could be attained by confinement within the PPRs, which effectively prevents the water from entering the coordination sphere of the europium ions. Thereby, the possible non-radiative deactivation by O-H vibrations could be further avoided in the presence of PPRs44. This finding is in agreement with the previously calculated reduced knr value, which is also responsible for the increased fluorescence intensities and monochromaticity of europium complexes upon interaction with the PPRs.

TEM study of the Eu[III]@PPRs supramolecular aggregates

How can PPRs effectively exclude the water molecules from the coordination sphere of europium ions? Studies from other researchers have shown that inclusion complexes based on F127 and cyclodextrins could be assembled into hollow nanospheres, flakes, and nanorods in aqueous solution35,45,46,47,48. However, no discernible production of ordered aggregates could be detected in the system of PPRs before the addition of europium complexes. This phenomenon could be explained by the better solubility of CMCD and enhanced electrostatic interactions between PPRs in a neutral solution (pH 7.4). As a result, the amphiphilicity of the copolymers and the aggregation behavior of PPRs were eventually disrupted by encapsulating F127 with CMCD. Nevertheless, a completely different phenomenon has occurred after the addition of the europium complexes, as demonstrated by the obvious typical Tyndall effects for all samples (Fig. 2, inset). This suggested the presence of numerous nanoaggregates within the solution28.

This hypothesis was confirmed by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Fig. 2) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Fig. 3) measurements. The results of DLS revealed that the hydrodynamic size of the aggregates ranged from 372 to 690 nm. The average particle size of Eu[III]@PPRs decreased as the H/G ratio increased. The morphology and size of these nanoaggregates were further analyzed by TEM. As shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. S4, black spherical aggregates with different particle sizes could be observed in the TEM images, of which particle size also decreased with the increasing H/G ratios. Furthermore, the average sizes determined by the TEM were smaller than the hydrodynamic size determined by DLS, indicating the existence of certain hydrophilic functional groups on the surface of the aggregates46. All of the spherical aggregates seen in the TEM images exhibited good contrast without adding any staining agent, suggesting electron-rich europium ions were gathered in the aggregates49. The distribution of the europium complexes could be verified by the elemental maps from EDX analyses for Eu (red), N (blue), and O (green). Analysis results in Fig. 4 show that the Eu, N, and O elements were uniformly distributed in the spherical aggregates at lower H/G ratios, with the N elements originating from the DPA ligand. This proved the DPA-coordinated europium complexes were indeed bound in these spherical aggregates and also explained the increased fluorescence monochromaticity when the europium complexes were trapped within the PPRs.

NMR study of the Eu[III]@PPRs supramolecular aggregates

Since the size of the aggregates was much larger than that of the micelles formed by F127, the spherical aggregates formed in the system were expected to be vesicles35,50. Meanwhile, the dimensions of the aggregates varied with the concentration of F127, implying that F127 plays a key role in the assembly of the aggregates. However, the concentration of F127 in the PPRs was unlikely to form vesicles by themselves. Based on the previous results of the size and element distribution, the assemblies obtained here were supposed to be formed by PPRs through coordination with europium complexes. The coordination aggregation of Eu[III], along with the host-guest effect between F127 and CMCD, is thought to be crucial for the formation of vesicles. To support this hypothesis, 1D1H and 2D 1H−1H ROESY NMR spectra were used to verify the presence of the host-guest and coordination interactions in the system.

Figure 5a showed the 1HNMR spectra of Eu[III]@PPRs with different H/G ratios. Coordination between the europium ion and the carboxymethyl substituent of CMCD was demonstrated by the weakening and right-shifting of the signals for the methylene proton (Hα) on the carboxymethyl substituent and the H1 proton next to the substituent of CMCD51,52. Furthermore, the protons inside the cavity of CMCD (H3 and H5) were observed to be upshifted in supramolecular aggregates compared to pure CMCD, while the chemical shifts of the protons on the outer surface of CMCD (H2 and H4) were only slightly affected by the guest molecule. This was an indication of a host-guest inclusion effect between the inner cavity of the CMCD and F12726,45,53. Correspondingly, signals assigned to protons in PPO chains of F127 (H-C) showed a changed hyperfine structure and shifted toward downfield after forming PPRs with CMCD. The variation of the peak shape can be attributed to the movements of the molecules were restricted by CMCD, which also proved the PPO blocks of F127 was included by the CMCD48. Meanwhile, the chemical shift for protons in PEO blocks of F127 (H-A) kept almost unchanged in all samples of Eu[III]@PPRs. This result confirmed the preferential interaction between CMCD and PPO blocks that only PPO blocks rather than PEO blocks were encapsulated into the cavity of CMCD.

In addition, the inclusion effect between F127 and CMCD in the Eu[III]@PPRs was further evidenced by the 2D 1H−1H ROESY NMR spectra and is showed in Fig. 5b. Theoretically, correlation signals in the spectra are expected to arise only from short-range and specific interactions54. The interactions between the protons of guest molecules and CDs can thus be reflected by the cross-peaks in the 2D 1H−1H ROESY NMR55. As shown in Fig. 5b, the magnetic resonance signal correlations marked by the red dashed lines were detected between the inner cavity protons of CMCD (H3 & H5) and the methyl protons of PPO (H-C). This finding confirms the presence of a host-guest interaction between the PPO blocks of F127 and the inner surface of the CMCD cavity.

SEM and AFM study of the Eu[III]@PPRs supramolecular aggregates

The vesicular characteristics of the spherical particles were further evidenced by the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM). As shown in Fig. 6a–d, the SEM results reveal spherical morphologies and average diameters similar to those observed in the TEM images. Meanwhile, the size and number of spherical particles in SEM images also increase with decreasing H/G ratio. In addition, the three-dimensional spherical structure of the nanoparticles can be better visualized compared to TEM, and detailed surface morphologies of the aggregates can be provided by SEM images. Collapsed and broken hollow sphere structures could be discerned in the enlarged images and positions that are marked with the orange arrows. All these evidences suggest that the aggregates were hollow vesicular morphologies rather than solid spheres. These morphologies and sizes from the SEM results were very similar to the hollow carbon nanoparticles prepared from F127 and α-cyclodextrin46.

The AFM images provide further evidence supporting the hollow structure of the aggregates. In the AFM image of Fig. 6e, particles with an average diameter of about 260–380 nm could be observed for samples of H/G = 20, the dimensions of which were in good agreement with the particle size seen in the SEM and TEM. Based on the sectional height profile shown in Fig. 6f, the particle height can be estimated to be 42 nm. The large diameter to height ratio obtained reflected the collapsed shell and hollow nature of the spherical aggregate. In view of the symmetrical structure of the vesicles, the thickness of the vesicle shell could be determined to be 21 nm26,53. This height is very similar to the size of F127 micelles in an aqueous solution35,50. Therefore, the vesicle wall of Eu[III]@PPRs can be inferred to be composed of an aggregated structure similar to F127 micelles. For vesicles with other H/G ratios, the aggregate diameters (380–580 nm) obtained from AFM images (Fig. S5) also aligned well with the observations from TEM and SEM. Although the AFM data for samples with lower H/G ratios exhibited uneven baselines due to vesicle stacking, the particle heights derived from the section height profiles (57–73 nm) were significantly smaller than their diameters, confirming the collapsed hollow sphere morphology of the spherical particles.

Based on the above results, the following schematic representation of the self-assembly behavior of supramolecular vesicles has been proposed in Scheme 1. The self-assembled building blocks of the vesicles are composed of PPRs and Eu[III], of which the inner layer is the PPO blocks encapsulated by CMCDs and the outer layer on both sides is the PEO blocks of F12746,56. These building blocks can be further assembled into vesicles by coordinating with Eu[III] via the carboxymethyl substituent of CMCD. The size of the vesicle changes with the amount of building blocks, which depends on the number of CMCD strung onto the F127. For a given concentration of CMCD, the number of building blocks formed by PPRs increases as the H/G ratio decreases, resulting in the formation of larger vesicles. This is beneficial for assembling more europium complexes into vesicles, which helps to reduce the deactivation of non-radiative vibrations through the shielding effect of PPRs. Therefore, a better fluorescence performance could be achieved in the Eu[III]@PPRs with lower H/G ratios.

Stimulus response properties of the Eu[III]@PPRs supramolecular aggregates

As is well known, one of the favorite characters of the supramolecular aggregates is the dynamic nature of the building blocks, which allows the reversible association and dissociation of the aggregates in response to different stimuli. Based on the dynamic nature of the host-guest interactions in the PPRs and the coordination interactions in the europium complexes, enzymatic and pH-stimulated response experiments were performed on the obtained supramolecular vesicles.

(a) Time-dependent emission intensity of Eu[III]@PPRs with different H/G ratios recorded at 615 nm versus hydrolysis reaction time in the presence of 100 U/mL α-amylase at 37.0 °C (λex = 286 nm). (b) The pH-dependent fluorescence spectra of Eu[III]@PPRs (H/G = 8) at different pH values (λex = 286 nm). The inset shows the variation of emission intensity recorded at 615 nm as a function of pH.

Enzyme responsive

Since 1,4-glycosidic bonds in β-CDs can be cleaved by α-amylase57, vesicles of the Eu[III]@PPRs are anticipated to be enzyme-responsive due to the degradation of CMCD. To demonstrate this, the fluorescence and morphology variation of Eu[III]@PPRs were studied in the presence 100 U/mL α-amylase at 37 °C. As shown in Fig. 7a, all the fluorescence intensity of the system recorded at 615 nm quenched with time after the addition of α-amylase and kept unchanged after 7 h. This indicates that the hydrolysis process was almost finished in 7 h. This response time is considerably longer compared to the enzyme response system with the similar enzymatic conditions23,26. Two factors may account for the comparatively long enzyme response time: first, the outer hydrophilic layer of the vesicle was composed of entangled PEO blocks of F127, which were thicker than those in the vesicles formed by small molecules. This will increase the resistance of the enzyme to enter the inner layer of the vesicle wall. Secondly, CMCDs in the vesicles not only interacted with F127 as host molecules, but also coordinated with europium ions via carboxyl substituents. Both interactions could increase the confinement effect of CMCD within the vesicle and delay the reaction with the α-enzyme. Although the CMCD concentration in the system was the same, the rate of the fluorescence decayed with the enzyme was different. This phenomenon can be accounted for the larger vesicles formed at lower H/G ratios are assembled by more building blocks than higher H/G ratios that can encapsulate more europium complexes. This results in a significant fluorescence enhancement of the europium complexes due to the more effective shielding effect by vesicles. When vesicles disassemble due to the hydrolysis of CMCD, the shielding effect disappears. At lower H/G ratios, this leads to a more significant quenching effect as more complexes are released from the vesicles. On the contrary, the fluorescence decreases slowly at higher H/G ratios, where fewer complexes are encapsulated and the shielding effect is less pronounced.

The changes in the structure of the Eu[III]@PPRs during enzymatic hydrolysis are also confirmed by DLS and TEM (Fig. S6). The DLS measurements in Fig. S4a revealed the disassembly of vesicles that aggregates with dimensions greater than 300 nm is less than 1% after the addition of α-amylase, and signals were mainly concentrated in the size range of 6–10 nm. This indicates that F127 molecules were in their unimeric state after the hydrolysis of CMCD50. In contrast to the results before enzymatic treatment, there was no appreciable presence of vesicles in the TEM images. Nevertheless, a few partially digested vesicles with undecomposed spherical structure were found in the samples after the addition of the enzyme (Fig. S6b and c). This proves the presence of CMCD in the vesicles and also shows the release of the bounded europium complex after enzymatic digestion.

pH responsive

Europium complexes with carboxylic acid ligands as sensitizing groups are known to be stable in a neutral environment but dissociated in acidic conditions. Such a pH-determined nature between europium ions and organic ligands is expected to result in a pH sensitivity in the fluorescence of the prepared vesicles. To prove this phenomenon, trace amounts of HCl aqueous solutions were added to modulate the pH value of vesicles prepared by Eu[III]@PPRs (H/G = 8). As can be seen in Fig. 7b, the emission intensities of the aggregates quenched with decreasing pH value. Variations in emission intensity of the aggregates at 615 nm were recorded and also plotted in the inset of Fig. 7b. When the pH value was decreased to 3.20, the fluorescence intensity was reduced to 6% of its initial value. This indicates that the europium complexes have dissociated from both the CMCDs and DPA ligands. Similar quenching effects had been obtained in other Eu[III]@PPRs with different H/G ratios (Fig. S7).

Moreover, peaks with sizes ranging from 54 to 125 nm appeared on the DLS curves for solutions when the pH of the system was reduced to about 1 by the addition of HCl (Fig. S8). The diameter of aggregates decreased as the H/G ratio increased. In line with this, low-contrast particles with an average diameter of 30–110 nm were also found in the TEM images (Fig. S9). The dimensions of the particles were much larger than the size of micelles formed by F127. In addition, the elemental analysis also revealed no aggregation of europium ions within the spherical particles. Therefore, we concluded that these small-sized aggregates were formed by dissociated PPRs. The aggregation of the PPRs can be explained by the decreased electrostatic repulsion and the increased hydrophobicity of CMCD, which is caused by the protonation of the carboxyl group upon the addition of HCl. As a result, PPRs clustered together after vesicle disintegration at lower pH.

Conclusions

In summary, we have successfully developed a size-adjustable fluorescent supramolecular vesicle (Eu[III]@PPRs) with dual stimulation responses to enzyme and pH. Through coordinating aggregation with PPRs, europium complexes can be assembled into vesicles and achieve improved fluorescence performance. The decreased water molecules in the coordination sphere of the europium complexes are responsible for the fluorescence enhancement, which is attributed to the binding and shielding effect of the PPRs in the vesicles. Moreover, not only the fluorescence intensity of the assemblies but also their sizes depend on the H/G ratio of CMCD and F127, which allows for selective loading of substances with different length scales. Upon the CMCD hydrolysis by α-amylase, the vesicles disassemble and release the assembled europium complexes, which is accompanied by a fluorescence quenching effect. As the pH of the system decreases, the weakened coordination interaction between PPRs and europium complexes triggers the degradation of the vesicles, and also results in a drastic decrease in the fluorescence. Compared with traditional methods of adjusting the size of lanthanide fluorescent vesicles, the method presented here can avoid the potential quenching effect caused by self-aggregation or other solvents. With their fluorescence-responsive nature and controllable properties, the obtained vesicles have the potential to be applied in optically diagnosing and treating diseases associated with abnormal enzyme expression.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Li, P. & Li, H. R. Recent progress in the lanthanide-complexes based luminescent hybrid materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 441, 213988 (2021).

Seo, S. E. et al. Recent advances in materials for and applications of triplet–triplet annihilation-based upconversion. J. Mater. Chem. C. 10, 4483–4496 (2022).

Binnemans, K. Lanthanide-based luminescent hybrid materials. Chem. Rev. 109, 4283–4374 (2009).

Feng, J. & Zhang, H. Hybrid materials based on lanthanide organic complexes: a review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 387–410 (2013).

Yang, D. Q., Li, H. M. & Li, H. R. Recent advances in the luminescent polymers containing lanthanide complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 514, 215875 (2024).

Ahmed, F., Hussain, M. M., Khan, W. U. & Xiong, H. Exploring recent advancements and future prospects on coordination self-assembly of the regulated lanthanide-doped luminescent supramolecular hydrogels. Coord. Chem. Rev. 499, 215486 (2024).

Cantuel, M. et al. Enhanced photolabelling of luminescent EuIII centres with a chelating antenna in a micellar nanodomain. Chem. Commun. 46, 2486–2488 (2010).

Debroye, E., Laurent, S., Elst, L. V., Muller, R. N. & Parac-Vogt, T. N. Dysprosium complexes and their micelles as potential bimodal agents for magnetic resonance and optical imaging. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 16019–16028 (2013).

Conn, C. E. et al. Lanthanide phytanates: Liquid-crystalline phase behavior, colloidal particle dispersions, and potential as medical imaging agents. Langmuir 26, 6240–6249 (2009).

Kotova, O., Bradberry, S. J., Savyasachi, A. J. & Gunnlaugsson, T. Recent advances in the development of luminescent lanthanide-based supramolecular polymers and soft materials. Dalton Trans. 47, 16377–16387 (2018).

Cheng, Q. H., Hao, A. Y. & Xing, P. Y. Stimulus-responsive luminescent hydrogels: Design and applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 286, 102301 (2020).

Roy, B. C. & Mahapatra, T. S. Recent advances in the development of europium (III) and terbium (III)-based luminescent supramolecular metallogels. Soft Matter 19, 1854–1872 (2023).

Huang, P. et al. Asymmetric vesicles self-assembled by amphiphilic sequence-controlled polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 10, 894–900 (2021).

Liu, H. W. et al. Recognition and discrimination of citric acid isomers by luminescent nanointerface self-assembled from amphiphilic Eu (III) complexes. Colloids Surf. A. 647, 129022 (2022).

Akhmadeev, B. S. et al. The incorporation of upper vs lower rim substituted thia-and Calix [4] arene ligands into polydiacethylene polymeric bilayers for rational design of sensors to heavy metal ions. Polymer 245, 124728 (2022).

Liu, J., Morikawa, M. A. & Kimizuka, N. Conversion of molecular information by luminescent nanointerface self-assembled from amphiphilic Tb (III) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 17370–17374 (2011).

Lei, H. R., Liu, J., Yan, J. L., Lu, S. H. & Fang, Y. Luminescent vesicular nanointerface: A highly selective and sensitive turn-on sensor for Guanosine triphosphate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 13642–13647 (2014).

Chen, F., Huang, P., Zhu, Y. J., Wu, J. & Cui, D. X. Multifunctional Eu3+/Gd3+ dual-doped calcium phosphate vesicle-like nanospheres for sustained drug release and imaging. Biomaterials 33, 6447–6455 (2012).

Banerjee, S., Bhuyan, M. & König, B. Tb (III) functionalized vesicles for phosphate sensing: Membrane fluidity controls the sensitivity. Sci. Rev. Chem. Commun. 49, 5681–5683 (2013).

Kuhn, P., Eyer, K., Allner, S., Lombardi, D. & Dittrich, P. S. A microfluidic vesicle screening platform: Monitoring the lipid membrane permeability of tetracyclines. Biochem. Anal. Biochem. 83, 8877–8885 (2011).

Schmidt, B. V. & Barner-Kowollik, C. Dynamic macromolecular material design—the versatility of cyclodextrin‐based host-guest chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8350–8369 (2017).

Liu, K. et al. Recent advances in assemblies of cyclodextrins and amphiphiles: construction and regulation. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 45, 44–56 (2020).

Hao, Q., Kang, Y. T., Xu, J. F. & Zhang, X. Fluorescence turn-on enzyme-responsive supra-amphiphile fabricated by host-guest recognition between γ-cyclodextrin and a tetraphenylethylene-sodium glycyrrhetinate conjugate. Langmuir 37, 6062–6068 (2021).

Alam, M. A. et al. Directed 1D assembly of a ring-shaped inorganic nanocluster templated by an organic rigid-rod molecule: An inorganic/organic polypseudorotaxane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 2070–2073 (2008).

Hu, W. T. et al. Recent development of supramolecular cancer theranostics based on cyclodextrins: A review. Molecules 28, 3441 (2023).

Xiao, X. et al. Enzyme-responsive molecular assemblies based on host–guest chemistry. Langmuir 37, 8348–8355 (2021).

Zhang, Y. M., Liu, Y. H. & Liu, Y. Cyclodextrin-based multistimuli-responsive supramolecular assemblies and their biological functions. Adv. Mater. 32, 1806158 (2020).

Pei, Q. et al. Cyclodextrin/paclitaxel dimer assembling vesicles: Reversible morphology transition and cargo delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 26740–26748 (2017).

Goren, E., Avram, L. & Bar-Shir, A. Versatile non-luminescent color palette based on guest exchange dynamics in paramagnetic cavitands. Nat. Commun. 12, 3072 (2021).

Li, Q. J. et al. Function-targeted lanthanide-anchored polyoxometalate-cyclodextrin assembly: Discriminative sensing of inorganic phosphate and organophosphate. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2104572 (2021).

Yao, H. et al. Lanthanide-mediated cyclodextrin-based supramolecular assembly-induced emission xerogel films: A transparent multicolor photoluminescent material. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 13048–13055 (2020).

Li, Z. Q., Wang, G. N., Wang, Y. G. & Li, H. R. Reversible phase transition of robust luminescent hybrid hydrogels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 130, 2216–2220 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Multifunctional pluronic P123/F127 mixed polymeric micelles loaded with Paclitaxel for the treatment of multidrug resistant tumors. Biomaterials 32, 2894–2906 (2011).

Tsai, C. C. et al. Supramolecular structure of β-Cyclodextrin and poly(ethylene oxide)-block-poly(propylene oxide)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) inclusion complexes. Macromolecules 43, 9454–9461 (2010).

Pepić, I., Jalšenjak, N. & Jalšenjak, I. Micellar solutions of triblock copolymer surfactants with pilocarpine. Int. J. Pharm. 272, 57–64 (2004).

Li, Q. F. et al. Hybrid luminescence materials assembled by [Ln(DPA)3]3− and mesoporous host through ion-pairing interactions with high quantum efficiencies and long lifetimes. Sci. Rep. 5, 8385 (2015).

Görller-Walrand, C. & Binnemans, K. Chapter 167. Spectral intensities of f–f transitions. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths Vol. 25, 101–264 (1998).

Görller-Walrand, C., Fluyt, L., Ceulemans, A. & Carnall, W. Magnetic dipole transitions as standards for Judd-Ofelt parametrization in lanthanide spectra. J. Chem. Phys. 95, 3099–3106 (1991).

Yi, S. J., Yao, M. H., Wang, J. & Chen, X. Highly luminescent and stable lyotropic liquid crystals based on a europium β-diketonate complex bridged by an ethylammonium cation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 27603–27612 (2016).

de Sá, G. F. et al. Spectroscopic properties and design of highly luminescent lanthanide coordination complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 196, 165–195 (2000).

Lei, N. N. et al. Enhanced full color tunable luminescent lyotropic liquid crystals from P123 and ionic liquid by doping lanthanide complexes and AIEgen. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 529, 122–129 (2018).

Li, Q. R. et al. Luminescent vesicles self-assembled directly from an amphiphilic europium complex in an ionic liquid. Langmuir 36, 2911–2919 (2020).

Horrocks, W. D. W. Jr & Sudnick, D. R. Time-resolved europium (III) excitation spectroscopy: A luminescence probe of metal ion binding sites. Science 206, 1194–1196 (1979).

Wu, L. L. et al. Excited-state dynamics of crossing-controlled energy transfer in europium complexes. JACS Au 2, 853–864 (2022).

Ji, R. et al. Acid-sensitive polypseudorotaxanes based on ortho ester-modified cyclodextrin and pluronic F-127. ACS Macro Lett. 4, 65–69 (2015).

Yang, Z. C. et al. Hollow carbon nanoparticles of tunable size and wall thickness by hydrothermal treatment of α-cyclodextrin templated by F127 block copolymers. Chem. Mater. 25, 704–710 (2013).

Qin, J. et al. Self-assembly of β-cyclodextrin and pluronic into Hollow nanospheres in aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 350, 447–452 (2010).

Nogueiras-Nieto, L., Alvarez-Lorenzo, C., Sandez-Macho, I., Concheiro, A. & Otero-Espinar, F. J. Hydrosoluble cyclodextrin/poloxamer polypseudorotaxanes at the air/water interface, in bulk solution, and in the gel state. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 2773–2782 (2009).

Yang, L. et al. Fluorescence enhancement by microphase separation-induced chain extension of Eu3+ coordination polymers: Phenomenon and analysis. Soft Matter 7, 2720–2724 (2011).

Cohn, D., Lando, G., Sosnik, A., Garty, S. & Levi, A. PEO-PPO-PEO-based Poly (ether ester urethane)s as degradable reverse thermo-responsive multiblock copolymers. Biomaterials 27, 1718–1727 (2006).

Wan, M. H. et al. Carboxymethyl β-cyclodextrin grafted Hollow copper sulfide@ mesoporous silica carriers for stimuli-responsive pesticide delivery. Colloids Surf. B. 228, 113425 (2023).

Wang, A. et al. Drug delivery function of carboxymethyl-β-cyclodextrin modified upconversion nanoparticles for adamantine phthalocyanine and their NIR-triggered cancer treatment. Dalton Trans. 45, 3853–3862 (2016).

Zhou, C. C. et al. Self-assembly of nonionic surfactant tween 20@2β-CD inclusion complexes in dilute solution. Langmuir 29, 13175–13182 (2013).

Crans, C. D., Rithner, C. D., Baruah, B., Gourley, B. L. & Levinger, N. E. Molecular probe location in reverse micelles determined by NMR dipolar interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4437–4445 (2006).

Jahed, V., Zarrabi, A., Bordbar, A. K. & Hafezi, M. S. NMR (1H, ROESY) spectroscopic and molecular modelling investigations of supramolecular complex of β-cyclodextrin and Curcumin. Food Chem. 165, 241–246 (2014).

Ghosh, S. et al. Organic additive, 5-methylsalicylic acid induces spontaneous structural transformation of aqueous pluronic triblock copolymer solution: A spectroscopic investigation of interaction of Curcumin with pluronic micellar and vesicular aggregates. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 11437–11448 (2014).

Park, C., Kim, H., Kim, S. & Kim, C. Enzyme responsive nanocontainers with cyclodextrin gatekeepers and synergistic effects in release of guests. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 16614–16615 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for the financial supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22002077), the Science and Technology Innovation Foundation of Shanxi Agricultural University (No. 2017YJ36 and 2017YJ42) and the Shanxi Province Basic Research Program Youth Science and Technology Research Fund (No. 202103021223332). The authors would like to thank Zhang Feiyan from Shiyanjia Lab (http://www.shiyanjia.com) for the DLS, TEM, SEM and AFM measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. J. Yi and F. Li performed the experiments and obtained the results. S. J. Yi was responsible for drafting the main body of the manuscript text, while Y. Y. Jiao prepared all the figures incorporated within the manuscript. J. Wang provided assistance in the analysis of the experimental results. Subsequently, all authors participated in the review process and made valuable contributions to the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yi, S.J., Li, F., Jiao, Y.Y. et al. An enzyme/pH dual-responsive supramolecular fluorescent vesicle with tunable size fabricated by europium complex and polypseudorotaxanes. Sci Rep 15, 7386 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92450-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92450-6