Abstract

Implicit sequence learning (SL) is crucial for language acquisition and has been studied in children with organic language deficits (e.g., specific language impairment). However, language delays are also seen in children with non-organic deficits, such as those with hearing loss or from low socioeconomic status (SES). While some children with cochlear implants (CI) develop strong language skills, variability in performance suggests that degraded auditory input (nature) may affect SL. Low SES children typically experience language delays due to environmental deprivation (nurture). The purpose of this study was to investigate nature versus nurture effects on auditory SL. A total of 100 participants were divided into normal hearing (NH) children, young adults, CI children from high-moderate SES, and NH children from low SES who were tested with two Serial Reaction Time (SRT) tasks with speech and environmental sounds, and with cognitive tests. Results showed SL for speech and nonspeech stimuli for all participants, suggesting that SL is resilient to degradation of auditory and language input and that SL is not specific to speech. Absolute reaction time (RT) (reflecting a combination of complex processes including SL) was found to be a sensitive measure for differentiating between groups and between types of stimuli. Specifically, normal hearing groups showed longer RT for speech compared to environmental stimuli, a prolongation that was not evident for the CI group, suggesting similar perceptual strategies applying for both sound types; and RT of Low SES children was the longest for speech stimuli compared to other groups of children, evidence of the negative impact of language deprivation on speech processing. Age was the largest contributing factor to the results (~ 50%) followed by cognitive abilities (~ 10%). Implications for intervention include speech-processing targeted programs, provided early in the critical periods of development for low SES children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Implicit sequence learning (SL) is the ability to automatically detect sequential patterns in the environment and subsequently make predictions about future events without conscious awareness1,2,3. It is fundamental to the general cognitive system and particularly to language acquisition. While there is ongoing debate about whether SL is a general learning mechanism or a domain-specific process, it is conventionally presumed that the linguistic system provides an optimal context for studying SL. Therefore, most studies explored SL within the linguistic domain in populations with innate deficits in speech and language processing, such as specific language impairment (SLI)4,5,6, dyslexia7,8, and developmental apraxia9,10. These studies showed partial, delayed, or absent SL6,8,9, as well as reduced memory consolidation to the learned sequence and higher susceptibility to interference11.

There are, however, other special populations, such as the hearing impaired and normal-hearing children from low socioeconomic status (SES), that exhibit language impairment due to deficits in the quality and quantity of either the acoustic input or the linguistic input, respectively. These two groups represent distinct cases of deficits in auditory input due to ‘nature’ (damaged auditory system in the hearing impaired) versus ‘nurture’ (poor linguistic input from low SES environment), both of which impact language performance. To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically compare auditory sequence learning in children with cochlear implants and children with low SES. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the effect of acoustic and linguistic deprivation on auditory SL by testing SL in deaf children who gained their hearing via cochlear implants (CI) and low SES children, respectively. Such information has both theoretical and clinical implications. Theoretically, the results will provide important insight as to whether degraded auditory input (of any type) influences SL, and if yes- whether it is influenced differently by the type of the degraded input (linguistic versus acoustic). Clinically, the findings could help identify vulnerable or impaired processes within special populations, allowing for targeted intervention to be applied accordingly.

To date, SL was investigated in hearing infants and children mostly in the visual modality12,13, under the assumption that SL is a general learning mechanism that testing in one modality is sufficient14,15. There are, however, several arguments in favor of testing SL in the auditory modality. One argument is that SL should be tested in the modality through which language is primarily acquired, that is, the auditory modality16,17. Another argument relates to the sequential temporal nature of SL, and therefore, the auditory modality is the appropriate environment in which to test it18. These arguments have been strengthened by the fact that significant correlations were reported between auditory SL and language abilities, whereas no such correlation was found with visual SL tasks within the same tested cohort19. Furthermore, auditory SL tasks (and not visual SL tasks) were found to discriminate between children with specific language impairment and typically developing peers20. Noteworthy is an ongoing debate as to whether auditory SL is a specific language-processing module due to the rule-governed structures and sequential patterns in the linguistic system or whether it reflects an ability that is not limited to speech sounds. van der Kant, Männel, Paul, Friederici, Höhle & Wartenburger21, for example, showed a developmental shift in young children when learning sequences of words in a foreign language, but not when learning tone sequences, as was demonstrated by fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy) responses, thus supporting a language-specific module. Others, however, showed an effect of repeated sequential tones or noises on participants’ behavioral and electrophysiological responses22,23, suggesting that SL reflects a general ability. Thus, whether SL in the auditory modality is specific to speech sounds or reflects a more general learning ability has yet to be determined.

Language and learning in hearing-impaired children with cochlear implants

Cochlear implants are the preferable auditory prostheses for children with severe-to-profound hearing loss who show little or no gain from hearing aids. The CI device includes an outer microphone and processor, which transforms the auditory signal into electrical pulses and delivers them to the inner part (the receiver) and to the auditory nerve via an array of electrodes implanted in the cochlea. Thus, the CI bypasses the damaged cochlea by directly stimulating neurons in the auditory nerve from which information is delivered to the auditory cortex. Each electrode delivers specific spectral information, and its location within the cochlea approximates the tonotopic mapping of frequencies of normal hearing24,25. Although the spectral and temporal capabilities of CI are considerably limited, especially in noise, compared to that of the healthy auditory system, some congenital deaf children who are implanted under 12 months of age can demonstrate language and speech abilities that are close to those of their normal-hearing peers thus allowing them to fully integrate into the hearing society26,27. However, not all children show good language abilities28,29 due to various factors, including age at implantation, use and gain from hearing aids before implantation, residual hearing, educational approaches, implant characteristics, duration of CI use, cognitive abilities, and maternal education30,31,32. These factors explain 50%–60% of the variability in CI performance, leaving considerable unknown sources of variability that have yet to be explained16,33,34. Some researchers believe the underlying source of spoken language problems in CI children mostly relates to their limited perceptual abilities35. Others, however, suggested that children with CI may use different learning strategies and memory processes compared to their normal-hearing peers to cope with the peculiar cognitive demands due to their hearing loss and CI device36.

Most studies investigated SL and other implicit learning processes in CI in the visual modality. Some reported intact SL ability in CI and hearing-impaired children in general37,38,39 while other studies showed reduced ability of visual SL40,41,42,43. These findings led to “the auditory scaffolding hypothesis”, which suggests that SL deficit shown in CI children in the visual modality indicates that the auditory system plays a significant role in developing the general ability to process sequential input18. Following this hypothesis, it’s expected that HI children with cochlear implants will show poor SL when tested in the auditory modality. This, however, has yet to be empirically confirmed.

Language and learning in low SES children

Normal-hearing children from low SES fundamentally differ from those in the CI group because they have an intact auditory system but lack sufficient linguistic exposure through meaningful interactions with their main caregivers44,45,46,47,48. This lack of linguistic exposure is further exasperated due to reduced parental responsivity, lack of enrichment activities, and poor family companionship49. Therefore, despite normal hearing sensitivity and a typically functioning auditory system, most studies that investigated language performance showed language deficiencies in almost all linguistic domains. These include poor lexical knowledge and limited vocabulary usage44,50,51,52,53, low levels of grammatical understanding and grammatical complexity in expression52,54,55, delayed acquisition of pragmatic skills and a lack of pragmatic sophistication53, and low scores on morphology tasks requiring morphological analysis and analogies56. The acquisition of phonological awareness and sensitivity in late development stages is delayed in low SES children57,58, although no SES effect on production accuracy was found59. Cognitive processes that were found to contribute to poor language performance in low SES children include poor executive functions, such as low inhibitory control, limited cognitive flexibility, and reduced working memory60,61,62.

While there is mounting evidence as to the damaging effects of poor linguistic input on language outcomes, little is known about their underlying learning processes. To date, we are aware of only one study that addressed implicit learning processes via statistical learning in the visual modality23 (another implicit learning process based on tracking probabilistic patterns in the input rather than sequential patterns as in SL), and none in the auditory modality. Using behavioral and event-related potential measures in a visual learning task of 13 low SES children (as measured by maternal education) compared to 11 high SES children aged 8–12 years, statistical learning was found to be a significant mediator in the association between parental education and two language measures.

In sum, very little is known regarding auditory SL in prelingually deafened children with cochlear implants and typically hearing children from low SES families. Both populations demonstrate language difficulties that stem from impoverished inputs but for different reasons—nature versus nature, respectively. In addition, no study has tested SL with linguistic and non-linguistic sounds. Children with language difficulties may have specific difficulties in SL with linguistic stimuli but not in non-speech learning sequences. On the other hand, testing SL with non-linguistic sounds that are unfamiliar, such as pure tones63,64, may have a negative effect on SL, especially in children65,66. In addition, testing with the two types of stimuli may help answer the ongoing debate as to whether auditory SL is specific to language stimuli. Such information will help support or negate the hypothesis of SL as a general learning ability and not a language-specific one. Therefore, in the current study, two types of stimuli were used: familiar environmental sounds (non-speech sounds) and syllables (speech sounds).

The goals of the present study were: (1) to explore and compare SL in the auditory domain using a serial reaction time task (SRT) in prelingually deaf children using CI from high-medium SES, hearing children from low SES homes, and normal-hearing children and young adults from high SES who served as controls; (2) to examine SL with speech sounds and environmental sounds to determine the specificity of the learning processes; (3) to determine whether age is a confounding factor on the SRT task; and (4) to test the association of cognitive abilities, such as working memory, attention and non-verbal intelligence on auditory SL.

Results

Group average medians of reaction time (RT) to the 108 stimuli in each of five blocks (nine repetitions of a 12 stimuli sequence in each block) for speech sounds and environmental sounds were calculated to create learning curves for the CI children from HSES homes (CI group), normal-hearing children from low SES homes (low SES group), and normal-hearing children and young adults from high SES homes (NH high SES).

Figure 1 shows learning curves for the CI group, the low SES group, and separate curves for the adults and the children from NH high SES group. The performance of NH high SES adults and children was separated in this graph to demonstrate developmental differences. However, further data analysis refers to the three defined groups (CI, low SES, NH high SES). It can be seen that all groups with both stimuli (with the exclusion of low SES with environmental sounds) show typical learning curves. That is, an expected decrease in RT from block 1 to block 3 (for the learned sequence A), an increase in RT in block 4 (when the new sequence B is presented), and another decrease in RT in block 5 (back to the previously learned sequence A).

Group learning curves showing the average median reaction times and standard error for each block of 108 stimuli sequence, and for each type of stimuli: speech sounds (solid line) and environmental sounds (broken line); for normal-hearing adults (n = 19) marked in ◇, normal-hearing children (n = 41) marked in ○, CI (n = 15) marked in ▢, and low SES (n = 25), marked in Δ.

Figure 1 also shows that the RTs were shorter for the NH high SES adults compared to children regardless of the type of stimulus. Also, for all NH participants, RT for speech sounds was prolonged compared to environmental sounds with the longest RT for speech in the low SES. In contrast, no prolongation for speech sounds (compared to environmental sounds) is observed for the CI group. Interestingly, the RTs of the environmental sounds are similar to all three groups of children regardless of hearing loss or economic status. These observations were further confirmed in the following statistical analyses.

Levene testing was used to assess the homogeneity of variances across the different groups. No significant difference in variance was found between the three groups in the SRT task with speech sounds. However, with environmental sounds, the variance differed between the three groups [F(2,97) = 6.1, p = 0.003], with higher variance in the two NH groups (low SES and high SES) than in the CI group. Therefore, reaction time data were log-transformed to reduce skewness. Negative values were treated by adding a constant to the data prior to transformation. Table 1 presents the results of the repeated measures ANCOVA on the log-transformed RT data, with Block and Stimulus Type as within-subject variables, the Group as a between-subject variable, and age as covariant. The ANCOVA included calculations of the main effects and all possible interactions. The significant interaction of Stimulus Type*Block followed by contrast analyses with Bonferroni correction showed that while for speech sounds the RT reduction between block 1st and block 3rd was significant (mean difference = 108.85 ms; p < 0.001) and evident of learning, RT difference of blocks 1–3 was not significant for the environmental sounds (mean difference = 48 ms; p = 0.18). This interaction confirmed a non-typical learning curve compared to a typical learning curve for speech sounds as shown in Fig. 2a. A second interaction that was found significant is Stimulus Type*Group. Contrast analyses with Bonferroni corrections showed significant differences in the mean RTs (across blocks) between the speech sounds and the environmental sounds in the hearing groups (mean differences of 201.74, 356.97 ms, for high SES and low SES, respectively), but with no significant difference in the CI group (mean difference of 24.91 ms) as shown in Fig. 2b.

The ANCOVA analysis also showed a main effect of the covariate variable age [F(1,96) = 105.6, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.52]. Figure 3a and b show the individual medians in block 5 (as a measure of the processing time in the final learned sequence) as a function of age for speech sounds and environmental sounds, respectively. The best-fit regression line for speech sounds was exponential (R2 = 0.56), and for environmental sounds was linear (R2 = 0.53). The correlation of block 5 with age was also explored separately for the CI, low SES, and NH high SES groups. In the NH high SES group (adults and children), significant and high correlations between the variables were shown for both types of stimuli, speech sounds and environmental sounds (r = -0.77; < 0.001 and r = -0.79, p < 0.001, respectively). Significant but lower correlations were found between age and SRT of block 5 for the CI group and the LSES group for speech stimuli only (r = -0.6, -0.56; p = 0.018, 0.004, respectively).

Individual data showing median RT in block 5 as a function of age (on a log10 scale) (a) for speech sounds and (b) for environmental sounds, in NH group (marked in Ο, n = 60), CI group (marked in ▢, n = 15), low SES group (marked in Δ, n = 25). Regression lines and R values are marked according to best fit.

Associations between SL and background variables in the CI group

No significant associations were found between the processing time in the final learned sequence (median RT of block 5) of the CI group and the duration of implant use or HAB word recognition score (p > 0.05). Similarly, t-tests for independent samples revealed no difference in processing time as reflected in RT of Block 5 between CI who were congenitally deaf to those with progressive hearing loss (p > 0.05).

Associations between SL, cognitive skills, hearing status, and SES

Pearson correlations controlled by age were conducted between cognitive test scores and block 5 RTs for each stimulus type for all the participants. One participant from the CI group was excluded from the analysis since she was a Yiddish speaker. The results of the correlations are presented in Table 2.

It can be seen that medium significant correlations were found between all three cognitive tests and the learning measure with speech sounds. However, with environmental sounds, only TMT showed a significant correlation with RT of block 5.

A hierarchical linear regression model was conducted to examine the relationships between the median RT in block 5 with speech sounds and environmental sounds and the three cognitive test scores across all participants. In the first step, age was entered into the analysis, and in the second step, the three cognitive scores were entered. The regression model for speech sounds was statistically significant for both steps [F(1,244.9) = 32.6; p < 0.001 for age only, and F(4,214.2) = 35.8; p < 0.001 for cognitive scores]. Age alone explained 46.5% of the variance in block 5 RT, and 60.3% of the variance was explained by the combined effect of age and the three cognitive scores. Hence, the addition of the cognitive scores explained an additional 13.8% of the variance. The TMT and digit span scores were significant predictors (β = 0.21, -0.23; p = 0.005, 0.008, for TMT and digit span, respectively). However, the Raven scores did not significantly contribute to the prediction of the block 5 RT. The regression model for environmental sounds was also statistically significant for both steps [F(1, 97) = 103.9, p < 0.001 for age only, and F(4, 94) = 36.3, p < 0.001 for cognitive scores]. Age alone explained 51.7% of the variance in block 5 RT, and 60.7% of the variance was explained by the combined effect of age and the three cognitive scores. Hence, the addition of the cognitive scores explained an additional 9% of the variance. Digit span and TMT scores were significant predictors of block 5 RT (β = -0.41, 0.33; p < 0.001, < 0.001 respectively), while Raven was not a significant predictor.

A second hierarchical linear regression model was conducted to examine the relationships between block 5 RTs with speech sounds and environmental sounds and the two categorical variables, hearing (NH vs CI) SES (high SES vs low SES). In the first step, age and TMT scores (as representing cognitive skills) were entered into the analysis as control variables; in the second step, the hearing status variable was entered, and in the third step the SES variable was entered. For the speech sounds, the model with the control variables alone was statistically significant [F(2,97) = 59.02; p < 0.001], explaining 54.9% of the variance in the dependent variable (R2 = 0.549). Hearing status did not significantly improve the model [F(1,96) = 0.97, p = 0.33, ∆R2 = 0.004]. Adding the SES variable significantly improved the model [F(1,95) = 12.49, p < 0.001, ∆ R2 = 0.052, β = − 0.26], explaining 5.2% of the variance. The final model explained 60.5% of the variance. For the environmental sounds, with the control variables the model was statistically significant [F(2,97) = 65.89, p < 0.001], and explained 57.6% of the variance. In contrast with the speech sounds model, adding hearing status to the model significantly improved it [F(1,96) = 11.29, p = 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.05], increasing the explained variance to 62.1%, and showing a significant negative effect of longer RTs with environmental sounds (β = − 0.232). Adding SES did not significantly impact the model (p = 0.5).

Discussion

This study is the first to systematically explore the effects of degradation in auditory input due to ‘nature’ versus ‘nurture’ deficits on auditory SL by testing hearing-impaired children with CI and children from low SES homes representing each of the deficits, respectively, in comparison to normal hearing high SES group. This is also the first study to investigate the effect of type of stimulus (speech versus nonspeech) on auditory SL by comparing speech and environmental sounds within the same participants. The data support the following novel findings: (1) All groups of participants demonstrated learning curves for both speech and nonspeech stimuli, suggesting that SL is a robust process resilient to degradation of auditory input and that it is not specific to speech; (2) Reaction time was found to be the sensitive measure for differentiating between groups and between types of stimuli. Specifically, normal hearing groups showed longer RT for speech compared to environmental stimuli, a prolongation that was not evident for the CI group; and, RT of low SES children was the longest for speech stimuli compared to other groups of children (including CI); (3) SES was a significant predictor to RT for speech sounds, with lower SES associated with poorer performance, but hearing status did not add to the speech sounds hierarchical model regression. In contrast, hearing loss negatively predicted performance with environmental sounds, but SES had no effect on the model; (4) RT of SL for speech sounds and environmental sounds is age dependent; and (5) auditory memory span, visual attention, and nonverbal intelligence together contributed to reaction time in a SL task beyond the influence of age. Age explained 46.5% and 51.7% of the RT variance (speech sounds and environmental sounds, respectively), and cognitive skills explained an additional 13.8% and 9% of the variance (speech sounds and environmental sounds, respectively).

The first of our findings that all groups of participants demonstrated learning curves, suggests that auditory SL, as tested in this study, is a robust process resilient to the long-term negative effects of the degraded linguistic or acoustic input. This was based on the relative RT results showing shorter RTs for the repeated (learned) sequence compared to longer RTs for the new sequence in all tested groups and stimuli. One possible explanation for the finding that auditory SL was evident in all tested groups, including the CI group and children from low SES, is related to the SL task used in the present study. Specifically, our participants were requested to press a key after each stimulus in the sequence, which is considered low-demanding on working memory. In contrast, studies where participants were requested to remember the entire sequence and then key what they heard is more difficult to perform because it is more cognitively demanding. In such studies, any prolongation of processing time for each individual sound may also create overlap and interference in the processing of the entire sequence at various perceptual and cognitive levels. Support for this explanation can be found in studies that showed intact visual SL in hearing-impaired individuals when requested to respond following a single stimulus37,39 but not when the task required repetition of sequences varying in length40,41,43.

The finding that degraded auditory input did not negatively affect auditory SL in CI children is in keeping with the findings of Hall et al.37, who showed SL in hearing-impaired and CI participants using the visual SRT task. Our findings are also in keeping with studies that showed that many CI children achieve remarkable speech and language outcomes despite limited auditory input provided by the device and the period of auditory deprivation prior to implantation26,27. These achievements are probably due to neural compensatory mechanisms that help them adapt and make the most of the auditory signals they receive. An example of such a compensatory mechanism is brain plasticity for those implanted under 2 years old, which is considered a critical period of auditory and language development, during which the brain is most receptive to learning and adapting to auditory stimuli67. This period is also sensitive to the development of some executive functions, such as learning, attention, sequential processing, and factual and working memory68,69. In the present study, 8/14 (57%) of the CI group were implanted under the age of 2 years, an age when the brain adapts well to new and different information. Therefore, it may not be surprising that these children showed learning on the auditory sequence task. The remainder of this group was implanted considerably later (> 3 years old) because they had residual hearing and were able to benefit from hearing aids. Early access to speech sounds, even if limited, contributes significantly to brain organization and neural connectivity between areas of the brain in the critical period of auditory, speech, and language development67. Thus, the audiological background of these children may explain their good SL. Note that this finding does not support the 'auditory scaffold hypothesis, which suggests that the auditory system plays a significant role in developing the general ability to process sequential input18 and, therefore, predicts poor SL in CI users18. This hypothesis was based on the finding of poor visual statistical learning in CI children. Hence, it is also possible that differences in the implicit learning task and tested modality contributed to the different outcomes of such studies. This should be investigated in future studies.

The second finding of longer RT for speech compared to environmental sounds for the normal hearing groups can be explained by the notion that the process of speech identification, processing, and reading the correct key on the keyboard is either more demanding or requires more stages toward decision-making compared to environmental sounds. Assuming RT reflects the accumulated processing time of these processes (including SL), it has been suggested that shorter RTs indicate more efficient neural processing, while longer RTs may suggest delays in processing including decision-making70,71. Why would processing speech stimuli on the SL task result in longer processing times? One possibility may be related to the fact that the SL with speech sounds involves reading the letters on the keyboard, adding complexity due to phonology-orthography coding. This symbolic sound-to-sign coding does not occur in responses to environmental sounds, which involve semantic processing when coding the sound to its source72,73. Another possible explanation is that the perception of syllables activates top-down processes in anticipation of a meaningful unit (e.g., a word)74,75,76. Such activation of additional processes aims to optimize and promote speech perception but may add to processing time. In contrast, no extra top-down anticipation processes are expected to occur when listening to an environmental sound. Thus, based on this explanation, it is possible that the auditory SL of environmental and speech sounds is mostly similar77 and that the additional prolongation for speech sounds may be related to post-stimulus processes. To resolve this issue, it would be of interest to select meaningful monosyllabic words that can be expressed in pictures.

A third possible explanation for the prolongation of RT for speech sounds may be the shorter time required to identify environmental sounds compared to speech sounds even though both types of stimuli are similar in duration (500 ms). Research suggests that differentiating between the vowels (e.g., /sa/ vs /si/ and /ta/ vs /ti/ would require identifying the transition to the vowels and formants and reported to be about 150 ms of auditory input for reliable discrimination78. The differentiation between the fricative and stop consonants (e.g., /sa/ vs /ta/ and /si/ vs /ti/) may require an even shorter duration of approximately 40–50 ms of auditory input. This period provides critical information on aspiration and the frequency patterns of the initial fricative noise allowing a confident distinction between phonemes79. In contrast, the time required for differentiating between known environmental sounds, such as a dog barking or bird chirping, typically falls within a range of 100 to 300 ms. Studies on auditory perception suggest that while rapid recognition of familiar sounds may take approximately 100–150 ms more accurate recognition may occur around 250–300 milliseconds80,81. Based on this information, one would expect RT for environmental sounds to be longer than those of speech sounds and not shorter as found in the present study. Although this explanation is not substantiated, future studies should test the duration of sound required to identify stimuli similar to those used in the present study.

The finding of similar RT between speech and environmental sounds for the CI children is interesting, considering the above explanations for the prolongation of speech compared to environmental sounds in the hearing groups. Moreover, average RTs for speech and environmental sounds of CI did not differ significantly from the NH group. These findings can be explained by different listening strategies used by CI compared to NH for the environmental sounds. It is suggested, for example, that NH children may have relied on an implicit conceptual process of the sound source when responding to environmental sounds (based on memorization of acoustic patterns due to repeated exposure to these sounds). In contrast, the CI group may have relied on a more explicit strategy of inner speech of the words for the sound source (the words: dog, bird, door, bell). Thus, activating such phonological processes increases processing time, manifested in longer RT. The possibility that CI children may have used explicit learning strategies is further supported by our findings of significantly smaller variance in the RT data for environmental compared to speech sounds. It has been shown that explicit learning strategies generally yield lower variance rates among learners82, while implicit learning processes can vary widely among individuals83. Also, studies reported that hearing-impaired children use more explicit strategies compared to implicit ones in NH84,85,86. For example, CI children demonstrated the use of explicit serial clustering strategies for word learning compared to NH, who used implicit strategies36. Using yet another different learning strategy, CI children may have relied on specific acoustic features for the categorization of environmental sounds (as a basis for identification), whereas NH peers relied on semantic contexts87. The hypothesis that CI children use different listening strategies for recognizing environmental sounds compared to NH requires further investigation.

The finding of significantly prolonged RT for speech SL in the low SES group compared to the other groups emphasizes the negative effect of language deprivation (and not acoustic deprivation) on the processing time of linguistic tasks in this group88. Low SES children have insufficient input of speech both in quality and quantity44,45,46,48, in contrast to unrestricted exposure to general auditory input of non-speech sounds. This may explain why RTs for environmental sounds of the low SES were similar to their high SES peers. For SL of environmental sounds, all NH children, regardless of SES, may have activated implicit processing relying on acoustic pattern memorization. However, in the speech SL task, listeners were also forced to activate phonological processes, possibly triggering related top-down processes at the conceptual-lexical level, in anticipation of a further meaningful speech context, as was explained previously. It is possible that these latter linguistic levels of processing may be insufficient and slower in low SES children. This hypothesis is supported by studies showing unclear boundaries of phonological categories and difficulties in the central processing of speech sounds in the late stages of perception89 in low SES children57,90,91. Furthermore, research has consistently shown that low SES children often experience difficulties in phonological awareness92,93,94, which were found to be highly associated with speech perception skills. Children who demonstrated low scores in phonological awareness tasks, such as syllable counting, initial consonant recognition, and phoneme deletion, were at high risk of poor performance on speech perception tasks, such as categorical perception of speech sounds, speech perception in noise, and minimal pairs discrimination95,96,97. Because speech perception skills are considered a prerequisite for normal language development17, the RT prolongation for speech sounds in low SES may provide important insight into the underlying processes, specifically learning processes, that influence language development in this population. To date, studies offer limited information regarding the means by which learning processes may influence language acquisition98. It has been suggested that linguistic input is translated into language acquisition through the learning processing systems99,100. Hence, a slow, unsuccessful, and inefficient learning process may result in delayed and/or prolonged acquisition of a language skill and a higher rate of linguistic errors. It should be noted that longer RTs were also found in behavioral and neural responses to different SL tasks in children with specific language impairment (SLI), suggesting slower, inefficient, and interfered IL processes in children with intrinsic innate language deficit11,101. This data supports the possibility that SLI and low SES share a common ground of difficulties in IL related to language difficulties.

The evidence of SL for both speech and non-speech stimuli in all tested groups supports the hypothesis that SL reflects a more general learning mechanism16,17,102 and not a specific one unique to a speech module103,104. However, the greater difference in the relative RT change in the first three blocks for the speech compared to the environmental sounds indicates faster learning that is unique to speech. One explanation for this finding may be related to the fact that processing speech sounds activates more cognitive processes resulting in faster learning, suggesting that environmental sounds require longer learning time. To test this hypothesis, future studies should include more blocks of training to the learned sequence prior to the exposure to the new sequence. It may be that after more training, SL with environmental stimuli will show learning similar to speech SL. Another possible explanation is that throughout their lifetime, participants had more exposure and general purposeful SL experience to speech sounds (for language development) compared to SL of non-speech sounds. Nonetheless, when the repeated pattern was violated (block 4), a strong and significant SL effect was demonstrated for both types of stimuli. It should be noted that studies that supported specific speech modules in implicit learning103,104 did not deny the existence of a general mechanism that is less tuned to non-speech stimuli. Following this notion, recent studies reframed a compromised approach, suggesting that components and constraints of general cognitive and auditory mechanisms shape basic processing, which is also specifically tuned for speech sounds105.

The fourth finding of the present study, that the RT measurement in the simple SRT task varies with age, is in alignment with the notion that RT reflects the accumulating effect of a combination of processes, including SL, auditory categorization, decision-making, motor preparation, and motor execution speed, all known to be developmental106,107. The RT reduction throughout childhood and young adulthood, particularly in the context of SL, can be attributed to general interrelated factors of neurodevelopmental processes and cognitive maturation. For example, maturational decrease in glutamate levels in the cerebral cortex and synaptic pruning refine the cortical networks and improve the efficiency of neural pathways108. The cognitive maturation effect may relate to developmental changes in cognitive control mechanisms that underpin RT, and exhibit a U-shaped trajectory across the lifespan, peaking during young adulthood109. The significant correlations between age and the scores for each of the cognitive tests in this study (r = -0.26, 0.47, 0.62; p = 0.006, < 0.001, < 0.001 for TMT, Raven, and digit span, respectively) support the association between cognitive maturation and RT. The finding of developmental changes in RTs in SL with speech sounds, but not with environmental sounds, in the CI group is of interest. For speech sounds, CI children showed a decrease in RT with age, as expected from the developmental trajectory (Fig. 3a). This finding supports the notion that the CI device provides appropriate acoustic input that allows the development of age-appropriate SL processing. The lack of a developmental decline of RT with age for the environmental sounds may be explained by the fact that most auditory training protocols for CI children utilize speech material. The exception is non-speech stimuli for auditory awareness training110. Thus, it may be that the RT for environmental sounds was more influenced by acoustic degradation, as CI children fail to develop a more immediate response to the acoustic patterns of the sounds, which may change as they grow older and accumulate listening experience. This notion can be tested by measuring the children’s RT for environmental sounds at an older age.

The last of our findings is that cognitive abilities (non-verbal intelligence, visual attention, and auditory working memory) explained 13.8% and 9% of the RT variance in the last SRT block (for speech and environmental sounds, respectively), in addition to the influence of age which explained 46.5% and 51.7% of the variance (for speech and environmental sounds, respectively). These findings emphasize the notion that SL is influenced by cognitive capabilities, as reported previously111,112,113,114,115,116. Our findings do not support the lack of involvement of higher cognitive skills in SL as reported by others117,118. Although cognitive skills were found to contribute to RT performance with both types of stimuli, they were stronger predictors of speech than environmental sounds. This finding supports our explanations related to the influence of higher levels of brain activation and processing in SL with speech sounds119,120. The findings also imply that speech SL may rely more heavily on working memory and executive functions, while SL with environmental sounds depends more on executive functions and fluid intelligence. Research indicates that auditory working memory plays a significant role in speech perception, which requires holding and manipulating sound patterns, especially under adverse listening conditions121. In contrast, while environmental sounds also engage in auditory memory, the processing demands may not be as high as those required for speech sounds.

The findings of the present study have theoretical and clinical implications. Theoretically, our findings support the notion that auditory SL is a basic ability of the cognitive system, as shown by its strong associations with other auditory and non-auditory cognitive tasks, as well as its resistance to the negative impact of degraded acoustic input. This is further supported by the findings that the negative impact of “nurture” factors was more pronounced than that of “nature” factors based on significant prolongation of the RTs for speech stimuli in the low SES group compared to other groups. This latter finding suggests that there is a potential overlap between SES-related delays in language development and auditory processing and that other more complex processes (e.g., categorization, decision-making, etc.) are specific to speech tasks. Clinically, the findings of the present study suggest that for low SES children, language intervention programs should also target speech sounds from the initial perceptual-phonological stages in order to improve auditory perceptual processing time. In addition, intervention and language support for low SES should begin much earlier than documented122 and preferably within the critical period for language development. Recent studies show that low SES infants have delayed early vocal and communicative behaviour (babbling, joint attention, first words) already in their first year of life123,124,125. Thus, there is a need to offer large-scale intervention programs for infants from low-SES families as early as possible126. The contribution of cognitive skills to SL performance suggests that cognitive training may enhance the improvement of learning processes. There is some evidence of cognitive training programs that positively influence language skills127,128. However, it is not clear whether cognitive training is associated with improved SL. This should be explored in future studies.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample size of the CI group was relatively small and heterogeneous in its background factors. This may have contributed to the lack of significant difference between the RT of speech and environmental sounds. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude whether the lack of such a difference in CI is due to atypical listening strategies for environmental sounds, for speech sounds, or both. Secondly, future studies should investigate SL in relation to language and speech perception skills. The third limitation is related to the lack of controlling for background parental factors which could impact the quantity and quality of the interactions and the linguistic input in CI and low SES children. These include parental stress levels, parental sensitivity skills, and parental communication style. Finally, SL should be explored through other learning tasks involving different levels of cognitive demands and methodology in order to be able to tease apart the possible effect of such variables on the results.

In summary, SL, via a simple auditory SRT task, was found to be resilient to the negative impact of deprived auditory and linguistic input caused by hearing impairment (nature effect) or by low SES environment (nurture effect), as evidenced by shorter RTs for a repeated sequence and higher RTs for a novel sequence. The effects of degraded auditory and linguistic input were evident through the RT values of the learning curves, which reflect a combination of processes including sequence learning but not limited to it. Thus, the simple SRT auditory allows the identification of SL ability separately from other cognitive abilities. The effect of CI was demonstrated by similar RT for speech and environmental sounds, whereas the effect of low SES was demonstrated through the significantly longer RT for speech sounds. The findings shed light on the specific processing and learning strategies in each special group and, hence, the specificity of the impact of the deficit. Thus, we propose that the relative RTs between blocks that demonstrated the SL and the RT values in the last block, indicating brain processing time, are two complementary SRT measurements. Integrating the information resulting from both measurements provides sensitivity to the occurrence of SL, together with specific features of SL in different populations and different types of stimuli. Finally, it should be noted that one cannot exclude the possibility that CI children may reflect more than “nature” deficits and low SES children more than “nurture” deficits. Both groups may be influenced by other factors. For example, CI children are also deprived of environmental auditory input during their first year of life and are at high risk of being influenced by maternal depression129 (a “nurture” effect). Similarly, low SES children may suffer from reduced maternal sensitivity130 and are at high risk of the negative effects of epigenetic factors131. Thus, comparing performance between CI and low SES children as representing the effects of 'nature vs nurture’ is more complex than originally thought and should be investigated in future studies.

Method

The present study was conducted following the ethical approval granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Tel Aviv university and at Shaare Zedek medical center under protocol number 0258–17-SZMC. All experimental procedures adhered to the guidelines and regulations set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki and the institutional policies governing human subjects’ research. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study, and in cases where participants were minors, consent was provided by their parents.

Participants

A total of 100 children and adults participated in this study. They were divided into 3 groups: the first group included 15 CI children from medium–high SES homes (CI group), a second group included 25 normal-hearing children which were recruited from low SES homes (low SES group), and a third group included 60 normal-hearing (NH) participants from two age groups: 41 children and 19 young adults (NH group). The demographic background information of the three groups is detailed in Table 3. Based on a developmental and educational questionnaire (for the adult participants or the children’s parents), all participants reported typical development of speech and language, and no other developmental difficulties currently or in the past. Participants in the NH group and the low SES group were tested for hearing prior to performing the learning tasks to confirm hearing levels within the acceptable normal hearing range for each ear separately (pure-tone air-conduction thresholds ≤ 20dBHL at octave frequencies of 500Hz, 1000Hz, 2000Hz, 4000Hz; bilaterally. ANSI, 1996)132. The CI children were all orally habilitated, and all but one child used bilateral (CI) or bimodal [CI + hearing aids (HA)] devices. Detailed background information of the individual CI participants is presented in Table 4. Note that CI children 1–8 were congenitally deaf and were implanted at a mean age of 1.06 years (SD = 0.23), whereas CI 9–15 had progressive hearing loss and were diagnosed by 3–5 years of age and were therefore implanted later (mean age 7.3 years, SD = 4 for this group). Also, with the exclusion of CI8 who was implanted with both CIs simultaneously, all other CI children had two devices implanted sequentially.

Participants from the NH and CI groups lived in medium–high SES homes. In this study, years of maternal education was used as a criterion for SES30,133. Specifically, maternal education of 12 years and below indicated low SES, whereas above 12 years indicated high SES. In addition, participants in the low SES group were recruited from a school in a disadvantaged neighborhood, which was ranked highly (7.5 points) in the socioeconomic index for schools defined by the Ministry of Education (http://edu.gov.il/sites/Shaar/Pages/madad_tipuach.aspx), indicating low SES of the students.

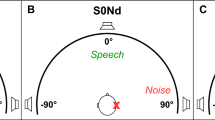

Stimuli

SL was investigated with two types of natural auditory stimuli: speech sounds and environmental sounds, which are meaningful and familiar to the children. The speech sounds included the syllables /sa/, /ta/, /si/ and /ti/. These were natural productions of three native Hebrew female speakers digitally recorded at a 41,000 Hz sampling rate. All sounds were identified correctly and immediately by five naïve listeners. These syllables were chosen as they contained frequent phonemes and were easy to perceive and discriminate (fricative versus plosive in consonants and low-mid versus high-front positioning of the tongue in the vowels) by CI users as well. The non-linguistic environmental stimuli set consisted of a dog barking, a bird singing, a knocking on a door, and a bell ringing. These were natural recordings, downloaded from a free- downloadable site (http://soundbible.com/about.php). These ES were also chosen as they were easily recognized and distinguished (high-frequency sounds vs low-frequency sounds, and animate vs inanimate sources of sounds). The duration of each stimulus, speech sounds or environmental sounds, was set to 500 ms (± 10 ms), and the stimuli was intensity normalized (RMS), using the Sony Sound Forge program, version 7.0 (2003). The four sounds in each set of sounds (environmental and linguistic) were used to create two sequences of 12 signals (template A and template B). These sequences were generated according to a specific arbitrary order following Nissen & Bullemer135 (see also Gofer-Levi, Silberg, Brezner, & Vakil, 2014; Lum et al., 2014)136,137. Each template was multiplied nine times to generate sequences of 108 sounds (two sequences of speech sounds and two sequences of environmental sounds). The sequence created from template A (“sequence A”) was presented repetitiously to participants in the learning task, and the sequence created from template B (“sequence B”) was presented once, as a novel sequence. Templates A and B are shown in Appendix 1.

Procedure

The Serial reaction time (SRT) task was similar to several previous studies135,138,139. The tasks with environmental and speech sounds were tested in two separate learning sessions. All participants were presented with identical sequences for each of the tasks. One session included five blocks, where in each block participants were presented with a sequence of 108 signals (as described in the stimuli subsection), depending on the type of stimuli (speech sounds or environmental sounds). Prior to each session, each participant was presented with the stimuli (3 presentations for each stimulus) to ensure correct and immediate recognition of the sounds. In the first three blocks of the session, participants were presented with sequence A. In the fourth block they were presented with sequence B. In the fifth block, participants were presented again with sequence A, to which they were exposed in the initial blocks. Participants were asked to press a matching key on the keyboard after the presentation of each signal, as accurately and as quickly as possible. A 750 ms interval separated between each response and the next sound. For each session, the five medians (one for each block) were connected to create a learning curve135. A typical learning curve included reduced RT from blocks 1–3 (reflecting learning of sequence A), increased RT from block 3 to block 4 (confirming that learning was not transferred to a new sequence- sequence B) and reduced RT from block 4 to block 5 when sequence A was introduced again (confirming again the learning of sequence A). A diagram of the procedure and an illustration of a typical learning curve are presented in Fig. 4.

(a) Illustration of the procedure design. Each rectangle represents one block with 108 stimuli which are made of 9 repetitions of a 12-stimulus sequence. Half of the participants were presented with speech sounds first (marked SS in the illustration), and the other half were presented with environmental sounds first (marked ES). (b) typically expected learning curves. That is RTs decrease in 1–3 block, increase in the 4th block, and increase in the 5th.

Each participant completed both sessions, with the order of presentation of environmental sounds and speech sounds counter-balanced between the participants. That is, about half of the participants completed first the speech sounds and then proceeded to the environmental sounds, while the other half completed the tasks in reverse order. In addition, all participants completed three cognitive tests assessing nonverbal intelligence using the Raven test, auditory capacity and working memory (using digit span), and visual attention using the trail making test (TMT). The Raven test (the modified version for children, Raven Manual, Sect. 1, 1998)140 consists visual patterns (60 and 36 patterns in the adult’s version and children’s version, respectively) with a missing piece, which is divided into three sets of 12. Participants were required to select one of six patterns to complete a visual display correctly, and the percentage correct was the dependent variable. Auditory capacity and working memory were examined using the forward digit span and backward digit span subtests of the ”Wechsler intelligence scale for children” (Wechsler, 1991). Participants heard pre-recorded sequences of numbers and were asked to repeat them in the same or the reverse order, respectively141. The criterion to continue to the next longer sequence was set at one successful repetition of the digit sequence, and the number of correctly repeated digits was the dependent variable. Visual attention span was examined by Trial Making test (TMT)142,143. Participants were asked to connect 25 numbers (1–25) scattered on a sheet of paper in ascending order as quickly as possible, without lifting the pencil from the paper. The time span of the task implementation (in seconds) was the dependent variable.

Apparatus

Testing was conducted in quiet rooms. Specifically, the two youngest groups of participants (from high SES and from low SES) were tested at their schools, the CI participants were tested at the hospital clinic, and the remaining participants were tested at their homes. Auditory signals were presented through a GSI-61 audiometer, and via THD-50 headphones for all NH participants, and via speakers for CI participants, at 45–50 dB sensation level, depending on their comfortable hearing level. SRT testing was controlled by a computer application developed for specific implicit learning studies purposes. The application collected the participants’ responses and calculated accuracy and reaction times. RTs were measured from the beginning of the stimulus presentation.

Statistical analysis

For each participant, accuracy rates and RTs were collected. In order to reduce the possibility that reaction times of children with CI may be influenced by their inability to correctly identify the stimuli via the auditory modality and those of low SES may be influenced by poor phoneme-to-grapheme coding, inclusion criteria included 85% accuracy. Based on this criterion, one CI participant and two children from low SES were excluded from the study, and their data was not analyzed. Thus, all 100 participants of the present study had accuracy scores above 85%.

Reaction times for the correct responses were recorded for each block separately for the speech sounds and environmental sounds sessions. Responses that were received in RT of 10 s and above were excluded, and the median of RT was calculated for each block for the correct responses only. Levene’s test was conducted to examine the variance in each group. The age variable was controlled as a covariate through a repeated-measured ANCOVA, which was performed on the log-transformed RT data to reduce skewness. The ANCOVA was defined with group variable as a between-subject variable, stimulus type (speech sounds vs environmental sounds), and block (1–5) as within-subject variables. ANOVA analysis with the order of session (speech sounds or environmental sounds first) as a between-subject variable, in addition to the group variable and block and stimulus type within-subjects variables), revealed no main effect of the order of session, but a significant interaction of stimulus type*block*order of session [F(3,67) = 3.23, p = 0.018, ƞ2 = 0.05]. Bonferroni analysis showed that the effect of the order of presentation was evident only in a slight reduction of the RTs in blocks 1 and 2 with SS when environmental sounds SRT was presented first. Accordingly, the variable 'order of presentation’ was excluded from the ANCOVA. The results suggest that absolute RT and not the relative RT between blocks was a differentiating factor between groups. Block 5 RT represents the final achievement of the absolute RT in the SRT task. It should also be noted that this measure was not found to be affected by the order of presentation. Pearson correlations were conducted between age and the median RTs of block 5 (SS and ES, separately) for all participants together and separately for each of the three groups (NH, CI, and low SES). Pearson correlation was also used to associate RT of block 5 with cognitive abilities and background variables. According to the correlation results, a linear multiple regression was conducted separately for speech and environmental sounds, to explain the variance in RT of block 5 by the three cognitive test scores. Another linear multiple regression model for speech and environmental sounds was conducted to explain variance in RT of block 5 by the two categorical variables of hearing status and SES in addition to age and cognition.

Data availability

Averaged SRT response data are included in this published article. All other data generated or analysed during this study are available upon request from S.C..

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Cochlear implant

- NH:

-

Normal hearing

- RT:

-

Reaction time

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- SL:

-

Sequence learning

- SRT:

-

Serial reaction time

References

Karpicke, J. D. & Pisoni, D. B. Using immediate memory span. Mem. Cognit. 32, 956–964. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196873 (2004).

Reber, A. S. Implicit learning of artificial grammar. J. Verb. Learn. Verb. Behav. 6(6), 855–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(67)80149-X (1967).

Willingham, D. B., Salidis, J. & Gabrieli, J. D. Direct comparison of neural systems mediating conscious and unconscious skill learning. J. Neurophysiol. 88(3), 1451–1460. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1451 (2002).

Evans, J. L., Maguire, M. J. & Sizemore, M. L. Neural patterns elicited by lexical processing in adolescents with specific language impairment: support for the procedural deficit hypothesis?. J. Neurodev. Disorders 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11689-022-09419-z (2022).

Lum, J. A., Conti-Ramsden, G., Morgan, A. T. & Ullman, M. T. Procedural learning deficits in specific language impairment (SLI): A meta-analysis of serial reaction time task performance. Cortex 51, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2013.10.011 (2014).

Ullman, M. T. & Pierpont, E. I. Specific language impairment is not specific to language: The procedural deficit hypothesis. Cortex 41(3), 399–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70276-4 (2005).

Katan, P., Kahta, S., Sasson, A. & Schiff, R. Performance of children with developmental dyslexia on high and low topological entropy artificial grammar learning task. Ann. Dyslexia 67, 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-016-0135-1 (2017).

Nicolson, R. I. & Fawcett, A. J. Development of dyslexia: The delayed neural commitment framework. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 13, 112. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00112 (2019).

Bombonato, C. et al. Implicit learning in children with Childhood Apraxia of Speech. Res. Develop. Disabil. 122, 104170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104170 (2022).

Iuzzini-Seigel, J. Procedural learning, grammar, and motor skills in children with childhood apraxia of speech, speech sound disorder, and typically developing speech. J. Speech, Lang. Hear. Res. 64(4), 1081–1103. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00581 (2021).

Desmottes, L., Maillart, C. & Meulemans, T. Memory consolidation in children with specific language impairment: Delayed gains and susceptibility to interference in implicit sequence learning. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 39(3), 265–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2016.1223279 (2017).

Lejeune, C., Desmottes, L., Catale, C. & Meulemans, T. Age difference in dual-task interference effects on procedural learning in children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 129, 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2014.07.007 (2015).

Meulemans, T., Van der Linden, M. & Perruchet, P. Implicit sequence learning in children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 69(3), 199–221. https://doi.org/10.1006/jecp.1998.2442 (1998).

Dienes, Z., & Altmann, G. (1997). Transfer of implicit knowledge across domains: How implicit and how abstract?', in Dianne C. Berry (ed.), How Implicit Is Implicit Learning? Debates in Psychology. Oxford, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198523512.003.0005

Saffran, J. R. & Wilson, D. P. From syllables to syntax: Multilevel statistical learning by 12-month-old infants. Infancy 4(2), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327078IN0402_07 (2003).

Boons, T. et al. Predictors of spoken language development following pediatric cochlear implantation. Ear Hear. 33(5), 617–639. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182503e47 (2012).

Kishon-Rabin, L. & Boothroyd, A. (2018). The Role of Hearing for Speech and Language Acquisition and Processing. In D. Ravid and A. Baron, (eds): Handbook of Communication Disorders: Theoretical, Empirical, and Applied Linguistic Perspectives. Mouton de Gruyter, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614514909

Conway, C. M., Pisoni, D. B. & Kronenberger, W. G. The importance of sound for cognitive sequencing abilities: The auditory scaffolding hypothesis. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 18(5), 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01651.x (2009).

Qi, Z., Sanchez Araujo, Y., Georgan, W. C., Gabrieli, J. D. & Arciuli, J. Hearing matters more than seeing: A cross-modality study of statistical learning and reading ability. Sci. Stud. Read. 23(1), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2018.1485680 (2019).

Gabriel, A., Meulemans, T., Parisse, C. & Maillart, C. Procedural learning across modalities in French-speaking children with specific language impairment. Appl. Psycholinguist. 36(3), 747–769. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716413000490 (2015).

van der Kant, A. et al. Linguistic and non-linguistic non-adjacent dependency learning in early development. Develop. Cognit. Neurosci. 45, 100819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100819 (2020).

Agus, T. R., Beauvais, M., Thorpe, S. J., & Pressnitzer, D. (2010). The implicit learning of noise: Behavioral data and computational models. In The Neurophysiological Bases of Auditory Perception (pp. 571–579). Springer New York.. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5686-6_52

Van Zuijen, T. L., Simoens, V. L., Paavilainen, P., Näätänen, R. & Tervaniemi, M. Implicit, intuitive, and explicit knowledge of abstract regularities in a sound sequence: an event-related brain potential study. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 18(8), 1292–1303. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2006.18.8.1292 (2006).

Kral, A. & O’Donoghue, G. M. Profound deafness in childhood. New Engl. J. Med. 363(15), 1438–1450. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0911225 (2010).

Perez, R. & Kishon-Rabin, L. (2013). Surgical devices (cochlear implantation-pediatric). In S. E. Kountakis (ed.): Encyclopedia of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614514909

Dettman, S. J. et al. Long-term communication outcomes for children receiving cochlear implants younger than 12 months: A multicenter study. Otol. Neurotol. 37(2), e82–e95. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000000915 (2016).

Wu, S. S. et al. Auditory outcomes in children who undergo cochlear implantation before 12 months of age: A systematic review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 169(2), 210–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/ohn.284 (2023).

Hansson, K., Ibertsson, T., Asker-Árnason, L. & Sahlén, B. Language impairment in children with CI: An investigation of Swedish. Lingua 213, 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2018.07.001 (2018).

Soleymani, Z., Mahmoodabadi, N. & Nouri, M. M. Language skills and phonological awareness in children with cochlear implants and normal hearing. Int. J. Pediat. Otorhinolaryngol. 83, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.01.013 (2016).

Rashid, V., Weijs, P. J., Engberink, M. F., Verhoeff, A. P. & Nicolaou, M. Beyond maternal education: Socio-economic inequalities in children’s diet in the ABCD cohort. PLoS One 15(10), e0240423. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240423 (2020).

Schauwers, K., Gillis, S. & Govaerts, P. Language acquisition in children with a cochlear implant. Develop. Theory Lang. Disorders 4, 95. https://doi.org/10.1075/tilar.4.07sch (2005).

Zaltz, Y., Bugannim, Y., Zechoval, D., Kishon-Rabin, L. & Perez, R. Listening in noise remains a significant challenge for cochlear implant users: Evidence from early deafened and those with progressive hearing loss compared to peers with normal hearing. J. Clin. Med. 9, 1381 (2020).

Ching, T. Y. et al. Outcomes of early-and late-identified children at 3 years of age: Findings from a prospective population-based study. Ear Hear. 34(5), 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182857718 (2013).

Dettman, S., Choo, D., Au, A., Luu, A. & Dowell, R. Speech perception and language outcomes for infants receiving cochlear implants before or after 9 months of age: Use of category-based aggregation of data in an unselected pediatric cohort. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 64(3), 1023–1039. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00228 (2021).

de Hoog, B. E., Langereis, M. C., van Weerdenburg, M., Knoors, H. E. & Verhoeven, L. Linguistic profiles of children with CI as compared with children with hearing or specific language impairment. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disorders 51(5), 518–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12228 (2016).

Kronenberger, W. G., Henning, S. C., Ditmars, A. M., Roman, A. S. & Pisoni, D. B. Verbal learning and memory in prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants. Int. J. Audiol. 57(10), 746–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2018.1481538 (2018).

Hall, M. L., Eigsti, I. M., Bortfeld, H. & Lillo-Martin, D. Auditory access, language access, and implicit sequence learning in deaf children. Develop. Sci. 21(3), e12575. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12575 (2018).

Klein, K. E., Walker, E. A. & Tomblin, J. B. Nonverbal visual sequential learning in children with cochlear implants: Preliminary findings. Ear Hear. 40(1), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000564 (2019).

von Koss Torkildsen, J., Arciuli, J., Haukedal, C. L. & Wie, O. B. Does a lack of auditory experience affect sequential learning?. Cognition 170, 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.09.017 (2018).

Bharadwaj, S. V. & Mehta, J. A. An exploratory study of visual sequential processing in children with cochlear implants. Int. J. Pediat. Otorhinolaryngol. 85, 158–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.03.036 (2016).

Conway, C. M., Pisoni, D. B., Anaya, E. M., Karpicke, J. & Henning, S. C. Implicit sequence learning in deaf children with cochlear implants. Develop. Sci. 14(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00960.x (2011).

Deocampo, J. A., Smith, G. N., Kronenberger, W. G., Pisoni, D. B. & Conway, C. M. The role of statistical learning in understanding and treating spoken language outcomes in deaf children with cochlear implants. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Schools 49(3S), 723–739. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_LSHSS-STLT1-17-0138 (2018).

Gremp, M. A., Deocampo, J. A. & Conway, C. M. Visual sequential processing and language ability in children who are deaf or hard of hearing. J. Child Lang. 46(4), 785–799. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000918000569 (2019).

Hoff, E. The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Develop. 74(5), 1368–1378. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00612 (2003).

Hoff, E. How social contexts support and shape language development. Dev. Rev. 26(1), 55–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2005.11.002 (2006).

Huttenlocher, J. Language input and language growth. Prevent. Med. 27(2), 195–199. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1998.0301 (1998).

Romeo, R. R. et al. Language exposure relates to structural neural connectivity in childhood. J. Neurosci. 38(36), 7870–7877. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0484-18.2018 (2018).

Samuelsson, S. et al. Genetic and environmental influences on prereading skills and early reading and spelling development in the United States, Australia, and Scandinavia. Read. Writing 20, 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-006-9018-x (2007).

Sarsour, K. et al. Family socioeconomic status and child executive functions: The roles of language, home environment, and single parenthood. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 17(1), 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617710001335 (2011).

Horton-Ikard, R. & Weismer, S. E. A preliminary examination of vocabulary and word learning in African American toddlers from middle and low socioeconomic status homes. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 16(4), 381–392 (2007).

Lawrence, J. F., Capotosto, L., Branum-Martin, L., White, C. & Snow, C. E. Language proficiency, home-language status, and English vocabulary development: A longitudinal follow-up of the Word Generation program. Bilingualism Lang. Cognit. 15(3), 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728911000393 (2012).

Nelson, K. E., Welsh, J. A., Trup, E. M. V. & Greenberg, M. T. Language delays of impoverished preschool children in relation to early academic and emotion recognition skills. First Lang. 31(2), 164–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723710391887 (2011).

Rowe, M. L. & Goldin-Meadow, S. Differences in early gesture explain SES disparities in child vocabulary size at school entry. Science 323(5916), 951–953. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1167025 (2009).

Eigsti, I. M. & Cicchetti, D. The impact of child maltreatment on expressive syntax at 60 months. Develop. Sci. 7(1), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00325.x (2004).

Jackson, S. C. & Roberts, J. E. Complex syntax production of African American preschoolers. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 44, 1083–1096. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2001/086) (2001).

Ravid, D. & Schiff, R. Morphological abilities in Hebrew-speaking gradeschoolers from two socioeconomic backgrounds: An analogy task. First Lang. 26(4), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723706064828 (2006).

Nittrouer, S. & Burton, L. T. The role of early language experience in the development of speech perception and phonological processing abilities: Evidence from 5-year-olds with histories of otitis media with effusion and low socioeconomic status. J. Commun. Disord. 38(1), 29–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.03.006 (2005).

Zhang, Y. et al. Phonological skills and vocabulary knowledge mediate socioeconomic status effects in predicting reading outcomes for Chinese children. Develop. Psychol. 49(4), 665–671. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028612 (2013).

Dodd, B., Holm, A., Hua, Z. & Crosbie, S. Phonological development: A normative study of British English-speaking children. Clin. Linguist. Phonet. 17(8), 617–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269920031000111348 (2003).

D’Angiulli, A., Herdman, A., Stapells, D. & Hertzman, C. Children’s event-related potentials of auditory selective attention vary with their socioeconomic status. Neuropsychology 22(3), 293. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.22.3.293 (2008).

Kishiyama, M. M., Boyce, W. T., Jimenez, A. M., Perry, L. M. & Knight, R. T. Socioeconomic disparities affect prefrontal function in children. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 21(6), 1106–1115. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21101 (2009).

Rosen, M. L. et al. Cognitive stimulation as a mechanism linking socioeconomic status with executive function: A longitudinal investigation. Child Develop. 91(4), e762–e779. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13315 (2020).

Jablonowski, J., Taesler, P., Fu, Q. & Rose, M. Implicit acoustic sequence learning recruits the hippocampus. PloS One 13(12), e0209590. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209590 (2018).

Saffran, J. R., Johnson, E. K., Aslin, R. N. & Newport, E. L. Statistical learning of tone sequences by human infants and adults. Cognition 70(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(98)00075-4 (1999).

Bannard, C. & Matthews, D. Stored word sequences in language learning: The effect of familiarity on children’s repetition of four-word combinations. Psychol. Sci. 19(3), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02075.x (2008).

Cycowicz, Y. M. & Friedman, D. Effect of sound familiarity on the event-related potentials elicited by novel environmental sounds. Brain Cognit. 36(1), 30–51. https://doi.org/10.1006/brcg.1997.0955 (1998).

Kral, A., Dorman, M. F. & Wilson, B. S. Neuronal development of hearing and language: cochlear implants and critical periods. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 42(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-080317-061513 (2019).

Thompson, A. & Steinbeis, N. Sensitive periods in executive function development. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 36, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.08.001 (2020).

Fiske, A. & Holmboe, K. Neural substrates of early executive function development. Develop. Rev. 52, 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2019.100866 (2019).

Kyllonen, P. C. & Zu, J. Use of response time for measuring cognitive ability. J. Intell. 4(4), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence4040014 (2016).

Prabu Kumar, A., Omprakash, A., Kuppusamy, M. & KN, M., BWC, S., PV, V. & Ramaswamy, P.,. How does cognitive function measure by the reaction time and critical flicker fusion frequency correlate with the academic performance of students?. BMC Med. Educ. 20, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02416-7 (2020).

Lewis, J. W. et al. Human brain regions involved in recognizing environmental sounds. Cerebral Cortex 14(9), 1008–1021. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhh061 (2004).

Martins, R., Simard, F. & Monchi, O. Differences between patterns of brain activity associated with semantics and those linked with phonological processing diminish with age. PLoS One 9(6), e99710. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099710 (2014).

Bonte, M., Parviainen, T., Hytönen, K. & Salmelin, R. Time course of top-down and bottom-up influences on syllable processing in the auditory cortex. Cerebral Cortex 16(1), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhi091 (2006).

Brodbeck, C. et al. Parallel processing in speech perception with local and global representations of linguistic context. Elife 11, e72056. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.72056 (2022).

Hickok, G. & Poeppel, D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8(5), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2113 (2007).

Stilp, C. E., Shorey, A. E. & King, C. J. Nonspeech sounds are not all equally good at being nonspeech. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 152(3), 1842–1849. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0014174 (2022).

Kanai, R., Lloyd, H., Bueti, D. & Walsh, V. Modality-independent role of the primary auditory cortex in time estimation. Exp. Brain Res. 209(3), 465–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-011-2577-3 (2011).

Gorina-Careta, N., Zarnowiec, K., Costa-Faidella, J. & Escera, C. Timing predictability enhances regularity encoding in the human subcortical auditory pathway. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37405 (2016).

Santoro, R. et al. Encoding of natural sounds at multiple spectral and temporal resolutions in the human auditory cortex. Plos Comput. Biol. 10(1), e1003412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003412 (2014).

Theunissen, F. & Elie, J. Neural processing of natural sounds. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15(6), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3731 (2014).

Tubau, E., Escera, C., Carral, V. & Corral, M. Individual differences in sequence learning and auditory pattern sensitivity as revealed with evoked potentials. Eur. J. Neurosci. 26(1), 261–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05637.x (2007).

Avraham, G., Morehead, J. R., Kim, H. E. & Ivry, R. B. Reexposure to a sensorimotor perturbation produces opposite effects on explicit and implicit learning processes. PLoS Biol. 19(3), e3001147. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001147 (2021).

Arfé, B. & Fastelli, A. The influence of explicit and implicit memory processes on the spoken–written language learning of children with cochlear implants. Oxford handb. Deaf Stud. Learn. Cognit. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190054045.013.18 (2020).

Lund, E. & Douglas, W. M. Teaching vocabulary to preschool children with hearing loss. Except. Child. 83(1), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402916651848 (2016).

Schirmer, A., Soh, Y. H., Penney, T. B. & Wyse, L. Perceptual and conceptual priming of environmental sounds. J. Cognit. Neurosci. 23(11), 3241–3253. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2011.21623 (2011).

Berland, A. et al. Categorization of everyday sounds by cochlear implanted children. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39991-9 (2019).