Abstract

Disc turbine impeller serves as a vital component of stirred-tank bioreactors and plays crucial role in optimizing their performance. This research integrates Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) with Taguchi experimental method to analyze the effects of blade curvature, asymmetry, and radial bending angles on disc turbine impeller performance. The designed P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° impeller maximizes the objective function \({E}_{V}\), balancing volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient \({k}_{L}a\) and power input per unit volume \(P/V\). Statistical analysis revealed that blade curvature significantly affected \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\), blade asymmetry substantially impacted \(P/V\) and \({E}_{V}\), and the radial bending angle exhibited a notable influence on \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\). The P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° impeller sustains an average oxygen transfer efficiency of 52.3% equivalent to that of the Rushton turbine (RT) impeller and 68.9% akin to the CD-6 impeller, while its average energy consumption is merely 31.2% and 46.1% of the RT and CD-6 impellers, respectively. The average \({E}_{V}\) of the P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° impeller is enhanced by 12.4% and 8% in comparison to the RT and CD-6 impellers, respectively. Conclusively, these results demonstrate that the P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° impeller offers economic and practical advantages in aerobic bioprocesses and presents new perspectives for advancing impeller design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, microbial fermentation has been increasingly applied to the production of renewable bioproducts, such as, biomethane1, biohydrogen2,3,4, bioethanol5,6, etc. During aerobic fermentation, stirred bioreactors play a key role, providing optimal mixing capacity and high oxygen supply to meet the growth and synthesis demands of microorganisms7. In practical operation, increasing the stirrer’s rotational speed and aeration rate can improve the mixing and oxygen transfer efficiency. However, this is typically accompanied by higher energy consumption8. In industrial-scale aerobic bioprocesses, the costs associated with aeration and agitation account for a significant portion of the total production costs9. Therefore, merely intensifying agitation and aeration not only increases energy consumption, but may also lead to unpredictable negative effects to the fermentation process, such as foaming, hyphal breakage, etc.

The performance of stirred bioreactor is determined by the height-to-diameter ratio, the number of blades, the type of blades, the sparger structure, and the operation conditions10,11. Numerous studies have emphasized the pivotal role that impellers play by their type and configuration in determining mixing and mass transfer characteristics within the bioreactor. The Rushton turbine (RT) impeller, characterized by its disc turbine configuration, has gained widespread acceptance in the microbial aerobic fermentation due to its exemplary mixing and mass transfer capabilities12. Nonetheless, a principal limitation of the RT impeller is its high power consumption, which significantly decreases with increasing aeration13. Inspired by cavitation theory14, researchers have orchestrated a series of novel disc turbine impellers by refining the curvature of the blades, encompassing designs such as a semicircular tubular disc turbine paddle (CD-6)15, an asymmetric parabolic disc turbine (BT)16, a Scaba 6SRGT impeller17, a half elliptical-blade disc turbine (HEDT), a parabolic disc turbine (PDT)18. Jia et al. designed the swept-back parabolic disc turbine (SPDT) and staggered fan-shaped parabolic disc turbine (SFPDT) impellers based on the PDT impeller. CFD simulation results showed that both turbines exhibited superior the power consumption, pumping capacity and mixing efficiency when compared to RT and PDT impellers19. Zheng et al. designed a fan-shaped turbine (FT) impeller that exhibited lower power number and higher relative power demand (RPD) compared to RT and BT impellers under turbulent flow conditions20. Jorge et al. designed five blade shapes to enhance the RT impeller, with the results suggesting that better performance may be achieved after retrofitting of Rushton turbines with streamlined impellers21. However, the existing research has primarily focused on the characterization of the designed blade shapes, lacking goal-oriented design ideas and systematic research on different blade shapes. A comprehensive study on the mass transfer capacity and power consumption of disc turbine impellers with different blade shapes has not yet been reported.

The development of novel impellers characterized by high mass transfer efficiency and low power consumption holds significant economic potential for the aerobic fermentation industry19. However, the design and development of impeller structures are resource-intensive, time-consuming, and require substantial financial investment. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), as an powerful and economical tool, has been extensively applied in the development of bioprocessing equipment22,23,24,25. Despite advancements in computational capabilities, the computing resources required for combinatorial design optimization that simultaneously considers multiple factors remain unaffordable. Fortunately, techniques based on the Taguchi method and statistical analysis have made it feasible to select and quantitatively evaluate optimized combinations of controlling factors. Through reasonable experimental design and accurate statistical analysis, the need for large sample sizes in simulations can be minimized. Numerous studies have successfully reported this approach in various fields, such as optimizing vertical axis wind turbine structures26, optimizing fermentation process parameters27,28, designing centrifugal pumps29, and so on. However, this method has not yet been systematically applied to the study of disc turbine blades.

This study integrated CFD with Taguchi methodology to optimize the structure of disk turbine blades for aerobic fermentation, aiming to enhance oxygen mass transfer efficiency and reduce power consumption. The Population Balance Model (PBM)30 and Higbie’s penetration theory were used to describe oxygen mass transfer. The \({E}_{V}\) defined as the balance between oxygen mass transfer and power consumption, was used as the objective function for the blade structure design. Initially, single-factor experiments were conducted to determine the optimal levels for three key factors: blade curvature, degree of asymmetry between upper and lower, and radial bending angle. Subsequently, an orthogonal experiment with three factors at three levels was designed to discover the optimal combination of controlling factors. Finally, the performance of the designed blade was evaluated under a range of operational conditions.

Materials and methods

Bioreactor equipment

Figure 1 illustrates the schematic structure of the experimental bioreactor used in this study. The reactor has a total volume of 94 L and is equipped with four symmetrical baffles, one ring-shaped sparger, and one impeller. The aim of this research is to optimize the design of the impeller blades, with all relevant structural parameters listed in Table 1.

\({\boldsymbol{\alpha }}_{{\varvec{g}}}\), \({{\varvec{k}}}_{{\varvec{L}}}{\varvec{a}}\) and \({\varvec{P}}\) measurement and calculation

Gas holdup \({\alpha }_{g}\)

Experimentally, the gas holdup \({\alpha }_{g}\) was determined based on the liquid height due to aeration, and it is described as:

where, \({\alpha }_{g}\) is gas holdup, %; \({H}_{0}\) denotes the initial liquid level height, m; \({H}_{g}\) represents the liquid level height after aeration, m.

In numerical simulations, the gas holdup \({\alpha }_{g}\) was calculated as follow:

where, \({\alpha }_{g}\) is gas holdup, %; \({V}_{c}\) is the volume of the cell, m3; \({\alpha }_{c}\) is the volume fraction of the gas phase in the cell, %.

Volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient \({k}_{L}a\)

Experimentally, the volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient \({k}_{L}a\) was determined using the steady-state sodium sulfite method31, with detailed experimental procedures and theoretical foundations provided in reference 32.

The Higbie’s penetration theory has been widely used in the calculation of mass transfer coefficients \({k}_{L}\) in gas–liquid two-phase systems and has been verified by experiments33,34,35,36. Its expression is as follows:

where, \(D\) represents the diffusion coefficient of oxygen in the liquid phase, m2/s; \(\varepsilon\) is the turbulent dissipation rate, m2/s3; \({\rho }_{l}\) is the density of the liquid phase, kg/m3; \({\mu }_{l}\) represents the viscosity of the liquid phase, kg/(m·s).

The interfacial area \(a\) can be calculated by Eq. (4):

The average bubble diameter \({d}_{b}\) was calculated as follows:

where, \({d}_{b,c}\) is the bubble diameter in the cell, m, \({V}_{c}\) is the volume of the cell, m3; \({\alpha }_{c}\) is the volume fraction of the gas phase in the cell, %.

Power input \(P\)

The power input \(P\) and power number \({P}_{o}\) of the bioreactor system can be calculated by measuring the torque on the impeller, with the specific calculation method as follows:

where, \(M\) represents the torque on the impeller, which is determined experimentally or numerical simulation, N·m; \(N\) is the rotational speed of the impeller, s-1; \(D\) is the diameter of the impeller, m.

CFD simulation

Governing equations for gas–liquid two-phase flow

To accurately describe the gas–liquid flow within the bioreactor, the Euler-Euler multiphase flow model37,38 was employed for characterization. In this model, the liquid serves as the continuous phase and the gas as the dispersed phase. The continuity and momentum equations are expressed as follows39:

where, \({\alpha }_{q}\), \({\rho }_{q}\) and \(\overrightarrow{{v}_{q}}\) are respectively the volume fraction, density and velocity of phase \(q\)(\(q\)=g for gas or l for liquid), \(\overline{\overline{{\tau }_{q}}}\) is the shear stress tensor, \(p\) represents the pressure of both phases, \(\overrightarrow{{F}_{q}}\) is the interphase forces.

The interphase forces include drag force, virtual mass force, lift force, wall lubrication force, and turbulent diffusion force, among others40. The formation of drag force is attributed to the non-uniform distribution of surface pressure resulting from the relative motion between the two phases. Its equation is described as below:

where, \({F}_{D,lg}\) is the drag force between two phases, \({C}_{D,lg}\) is the drag force coefficient, which can be described by various drag force models40,41,42.

Turbulence equations

The standard \(k-\varepsilon\) model was used to describe the turbulent flow characteristics of the liquid in this study. Its governing equations are expressed as43:

where, \({C}_{\varepsilon 1},{C}_{\varepsilon 2},{\sigma }_{k},{\sigma }_{\varepsilon }\) are model constants, which are 1.44,1.92,1.0 and 1.3, respectively. \({P}_{kb}\) and \({P}_{\varepsilon b}\) represent the influence of buoyancy, \({\mu }_{tl}\) is the turbulent viscosity of liquid phase, and \({P}_{k}\) is the turbulent phase caused by viscous force.

Population balance model

Modeling the bubble size distribution is crucial for accurately simulating oxygen transfer processes. Bubbles are subject to coalescence and breakup under the action of static pressure and interphase forces, leading to an uneven distribution of their sizes throughout the bioreactor28. Therefore, most previous studies34,44 that assumed a constant bubble size are inherently biased. Fortunately, the PBM model30 can approximately simulate the evolution of bubble sizes within the bioreactor, thereby improving the accuracy of the simulation. In a related study, Gu et al.23 employed CFD simulations combined with the PBM model to accurately predict the gas holdup distribution, cavity formation, and bubble size distribution during gas–liquid dispersion in stirred tanks equipped with RT impellers and self-similar impellers. Additionally, Chen et al.45 simulated the gas–liquid flow characteristics in stirred tanks with five different impeller combinations and designed an industrial-scale bioreactor based on a constant \({k}_{L}a\).

The equation for the PBM model is expressed as:

where, \({n}_{i}\) is the number of bubbles per class \(i\). \({B}_{{B}_{ic}}\), \({D}_{{B}_{ic}}\), \({B}_{{B}_{ib}}\), \({D}_{{B}_{ib}}\) denote the rates of bubble breakup to generate small bubbles, the reduction rate of large bubble breakup, the rate of small bubble coalescence to form large bubbles, and the reduction rate of small bubble coalescence, respectively.

where, \(a\left({v}^{\prime},v\right)\) is the coalescence rate between bubbles of size \(v\) and \({v}^{\prime}\); \(g(v)\) is the breakup rate of bubbles of size \(v\); \(g({v}^{\prime})\) is the breakup frequency of bubble \({v}^{\prime}\); \(\beta \left(v|{v}^{\prime}\right)\) is the probability density function of bubbles broken from the volume \({v}^{\prime}\) in a bubble of volume \(v\).

This paper adopts the model posited by Prince and Blanch46 to elucidate the phenomenon of bubble coalescence, which hypothesizes that the merging process of two bubbles comprises three distinct phases: initially, the bubbles engage in mutual collision, extruding the liquid present between them; thereafter, the liquid film separating the bubbles progressively attenuates until it reaches a critical thickness; ultimately, the film ruptures, leading to the union of the bubbles. Consequently, the model suggests that the rate of bubble coalescence is contingent upon the collision frequency and the efficiency of these collisions, namely:

where, \({\theta }_{ij}^{T}\), \({\theta }_{ij}^{B}\) and \({\theta }_{ij}^{S}\) respectively denote the contributions of turbulence, buoyancy, and shear forces to the bubble collision frequency, with \({\eta }_{ij}\) representing the collision efficiency, which is calculated as follows:

where, \({h}_{o}\) represents the initial liquid film thickness, \({h}_{f}\) is the critical thickness of liquid film breakup, and \({r}_{ij}\) is the bubble equivalent radius.

where \({r}_{i}\) and \({r}_{j}\) are the radii of bubbles \(i\) and \(j\), respectively.

The contribution of turbulence to the collision frequency is expressed as:

where \({F}_{CT}\) is the correction factor and the cross-sectional area of the collision bubble is expressed as:

The turbulent velocity is given by:

The contribution of buoyancy to the bubble collision frequency is expressed as:

and \({F}_{CB}\) is a calibration factor for the buoyancy. The contribution of shear to the collision frequency \({\theta }_{ij}^{S}\) is ignored.

The bubble breakup is based on the theories of isotropic turbulence and probability and the Luo and Svendsen breakup model47 is used to describe the breakup of bubbles.

where \(\xi\) is the dimensionless isotropic turbulent vortex size.

Simulation setup

The 3D models of the bioreactor were developed using Creo 9.0 software, retaining only the main structures such as baffles, impellers, and the ring-shaped sparger. The computational cells were generated using FLUENT MESHING software, and the polyhedral mesh was employed in all simulation cases due to its simplicity in drawing, reduced number, and faster solution speed. Preprocessing and computational solutions were conducted using FLUENT, with water (density \(\rho\) = 1000 kg/m3 and viscosity \(\mu\) = 0.001 Pa·s) and air selected as the materials for two-phase flow simulation. The surface tension was set to 0.073 N/m. The drag force model is selected as grace model, and other interphase interaction forces are slightly selected28. Drawing on experimental observations32, bubble sizes within the Population Balance Model were configured to range from 0.4 mm to 9 mm. The Discrete method was employed to divide the bubbles into 10 groups, with the Ratio Exponent set to 1.5, the min diameter set to 0.4 mm, and the First Order Upwind scheme used for solving. The Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) method was employed to simulate the rotation of the impellers. The stirring speed of the impeller was set at 200 rpm and the ventilation rate of the air inlet was 0.28 m/s. The air inlet was configured as velocity-inlet, and the outlet was set as degassing, while all other boundary conditions were defined as walls. The phase-coupled SIMPLE algorithm was employed for the steady-state solution. The rest of the solution settings take FLUENT’s default options. The convergence residual was set to 10–5, and the solver process monitored the torque of the impellers, with convergence considered achieved upon stabilization. CFD-POST was utilized for the visualization and numerical analysis of the simulation data.

CFD-Taguchi Experiment

Design objectives

Previous research has typically employed gas holdup \({\alpha }_{g}\), interfacial area \(a\), volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient \({k}_{L}a\), and power consumption \(P\) as objective functions for reactor design optimization20,37,38,48. In large-scale aerobic biological fermentation processes, aeration and agitation represent a substantial portion of the input costs, corresponding to oxygen transfer rates and power input per unit volume, respectively. These two metrics generally exhibit opposing trends; thus, the aim of this work is to achieve a higher \({k}_{L}a\) while minimizing \(P/V\). Consequently, following the recommendation of references27,28, the \({E}_{V}\) is adopted as the objective function for design optimization.

where, \({E}_{V}\) is comprehensive evaluation index, \(({k}_{L}{a)}^{\prime}\) and \({(P/V)}^{\prime}\) are normalized indexes of \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), respectively; \({\eta }_{1}\) and \({\eta }_{2}\) are weighted values of \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\). Here \({\eta }_{1}={\eta }_{2}=0.5\).

Single-factor experiments

Coefficient a

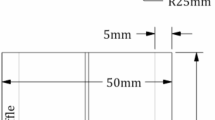

Parabolic equations can be effectively employed to design blade shapes, where the coefficient a in the quadratic Eq. (14) controls the curvature of the blade. A larger value of coefficient a results in a more pronounced curvature of the blade. Figure 2 illustrates the blade shapes at varying curvatures while maintaining the same blade height, with the RT impeller as a reference (where coefficient a is considered to be 0). The values of coefficient a are sequentially 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15 and 0.2.

Asymmetry

The prototype design of disc turbine impeller blades exhibited vertical symmetry relative to a central disk12. However, subsequent research has highlighted the superiority of asymmetrically designed blades in terms of mixing and power consumption16. In recognition of the discrepancies in flow field conditions encountered by the upper and lower sections of the impeller, five distinct asymmetric patterns for the blade sections have been developed, with detailed representations provided in Fig. 3.

Radial bending angle

It has been revealed that the radial bending of the blades can substantially diminish the power number of the impeller while preserving the efficiency of gas–liquid mass transfer19,22,49. Five distinct blade radial curvature angles were conceptualized within this research, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Orthogonal experiments

Full-factorial experiments are inherently time-consuming and less efficient when tackling multi-parameter optimization issues. In contrast, orthogonal experiments offer a more efficient, faster, and cost-effective approach to experimental design, significantly reducing experimental costs50,51. The optimal levels for three factors: coefficient a, asymmetry, and radial bending angle were determined by analyzing the results of single-factor optimizations. Subsequently, the control factors and their levels for the orthogonal experiment were established, as presented in Table 2. This study designed an L9(33) orthogonal experiment, as shown in Table 3, provided the names of the impellers for each case. Figure 5 illustrates the structure schematic of the impellers in each case, with the impellers rotating clockwise.

Impeller performance evaluation

CFD simulations were conducted to examine the performance of the designed impeller, the RT and CD-6 impellers, across a spectrum of operational conditions, including varying rotational speeds (100–500 rpm) and ventilation rates (0–1.8 vvm), to evaluate the versatility of the designed impeller. In addition, dimensionless parameters such as Reynolds number (\(Re\)) and Froude number (\(Fr\)) were introduced to quantify the flow state within the reactor.

For Reynolds number:

where \(\rho\) represents the liquid density (kg/m3), \(n\) denotes the stirring speed (r/s), \(D\) is the diameter of the impeller (m), and \(\mu\) is the dynamic viscosity (Pa·s).

For Froude number:

where \(g\) represents the acceleration of gravity (m/s2), \(n\) denotes the stirring speed (r/s), \(D\) is the diameter of the impeller (m).

Results and discussion

Model validation

Mesh independence verification

FLUENT software is based on the finite volume method for calculation and solution43. During the discretization of the computational domain, the cell size significantly affects the calculation results. Consequently, it is imperative to mitigate the influence of cell quality on simulation outcomes prior to conducting the simulations. In this study, five different cell configurations were generated for a specific type of impeller, and their effects on the variables \({k}_{L}a\), \({\alpha }_{g}\), average liquid velocity, and average gas velocity were compared. As depicted in Fig. 6, when the cell counts were 159w and 249w, the differences in \({k}_{L}a\), \({\alpha }_{g}\), average liquid velocity, and average gas velocity were merely 0.76%, 0.03‰, 0.24%, and 0.08% respectively. Consequently, a cell count of 159w was adopted as the standard for all subsequent simulations to minimize computational resource demands.

Model accuracy verification

Figure 7 illustrates the discrepancy between the experimental measurements and the CFD simulation results for \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P\) under varying rotational speeds and airflow rates. For \({k}_{L}a\), the CFD simulation results are in high agreement with the experimental results at 200 rpm, 1 vvm and 300 rpm, 1 vvm, with errors of -0.7% and -0.34%, respectively. Additionally, all simulated errors fall within the range of ± 20%. For \(P\), the CFD simulation results are slightly higher than the experimental values as a whole. Considering the simplification of the model and discrete errors, the errors are still within the acceptable range, which also shows the reliability of the CFD model. Consequently, in this study, the CFD model was utilized to evaluate the performance of various impellers, thereby reducing the costs associated with experimental and temporal resources.

Analysis of single-factor experiments

Single-factor experiments were conducted to design blade shapes and to determine the optimal levels of three control factors. The values of \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\) at varying coefficients a are depicted in Fig. 8 A, B, and C, respectively. The blade curvature incrementally increases with the augmentation of the coefficients a, whereas both \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\) exhibit a gradual descending trend, their decrement rates slowing progressively. This indicates that when the blade curvature attains a certain magnitude, the effects of the clearance and the free surface on the radial jet angle becomes smaller52, and its impact on \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\) diminishes substantially, leading to a stabilization of the impeller’s performance. The \({E}_{V}\) displays an initial increase followed by a decline, reaching a maximum value when the coefficient a is 0.15.

Figure 8 D, E, and F illustrate the simulation results based on the blade curvature at coefficient a of 0.15, with the asymmetry of the blades altered. The blades were divided into upper and lower sections by a disk. As the blade height decreased in both sections, \({k}_{L}a\) values generally decreased. Notably, the upper section had a greater influence on \({k}_{L}a\), with reduction percentages of 15.14% and 10.7% for the upper and lower sections, respectively. The \(P/V\) decreased with the reduction in blade height in the upper section and exhibited a fluctuating trend with the decrease in the lower section. The upper section had a more significant impact on \(P/V\), consistent with the changes in \({k}_{L}a\). This indicates that the shape of the upper blade section, compared to the lower section, more significantly determines the gas–liquid mass transfer capability and power consumption of the impeller, and should be a key consideration in impeller design. Under the asymmetric shape of T20B10, the impeller performance was poorest, corresponding to the smallest \({E}_{V}\) in Fig. 8 F. When the blade heights were T15B20, the target function \({E}_{V}\) reached its maximum value of 0.61, indicating optimal impeller performance.

Based on blade curvature coefficient a of 0.15 and the blade’s upper and lower section heights being T15B20, the simulated values of \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\), obtained from blades bent radially, are depicted in Fig. 8 G, H, and I, respectively. Blades bent in the direction of impeller rotation (AP15°, AP30°) increase the interaction between the blades and the fluid, resulting in fluid retention within the impeller, manifested as increased resistance and higher gas holdup (data not shown). Conversely, blades bent in the opposite direction to impeller rotation (AM15°, AM30°) allow the fluid to move in the direction of the bend, thus exhibiting a trend of reduced resistance and lower gas holdup, offering better discharge and energy-saving advantages, and being less prone to blade wear22,49. Overall, the simulation results indicate a synchronous decline in both \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\) as the blade curvature varies across different angles (AP30°, AP15°, A0°, AM15°, AM30°). Consequently, this trend is also reflected in the relatively modest fluctuation of the \({E}_{V}\). When the blade is bent at AM15°, the \({E}_{V}\) value is slightly higher than that at the other four angles. Therefore, through single-factor experimental optimization, the optimal levels for the target function \({E}_{V}\) can be determined as coefficients a = 0.15, T15B20, and AM15° for the three control factors.

Orthogonal experiments based on CFD modeling

Distributions of gas holdup \({\alpha }_{g}\), interfacial area a and volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient \({k}_{L}a\)

Figure 9 presents the numerical cloud plots of gas holdup \({\alpha }_{g}\), interfacial area a and volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient \({k}_{L}a\) for all cases. Upon entry, gas is dispersed by the impellers, resulting in significant bubble breakup, with higher values of \({\alpha }_{g}\), interfacial area a and \({k}_{L}a\) primarily distributed in the impeller and inlet regions, showing a consistent trend. Compared to the effects of agitation speed, ventilation rate, and impeller type, the impact of blade structure variations on these parameters is relatively minor28,53. The ranges of \({\alpha }_{g}\), interfacial area a and \({k}_{L}a\) are mere 0.82%, 5.84 m-1, and 0.0065 s-1, respectively. However, significant differences in the overall distribution within the reactor remain under different blade shapes, particularly evident in the upper regions of the impeller. The regions of high values of \({\alpha }_{g}\), interfacial area a and \({k}_{L}a\) in the bioreactor at different cases show an overall trend of decreasing from top to bottom and from left to right in Fig. 9. With the increase of the blade curvature and the decrease of the height of the upper part of the blade, the contact area between the blade and the fluid is reduced, which further reduces the ability of the blade in gas dispersion, bubble breaking and mass transfer. With the increase of the radial bending angle of the blade, the radial discharge of the impeller is weakened, and the upward lift of the gas and the circulation of the fluid make the gas above the impeller concentrated in the vicinity of the mixing shaft. Overall, designing the blade shape is necessary to optimize gas–liquid distribution and mass transfer.

Statistical analysis of control factors

The performance statistics of the influence of different levels of each factor on the target response can be obtained by calculating the average target responses at each level. Figure 10 displays the average values for gas holdup \({\alpha }_{g}\), bubble diameter d, interfacial area a, volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient \({k}_{L}a\), power input per unit volume \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\) for varying levels of each control factor. As shown in Fig. 10, with the increase in coefficient a, a consistent linear decrease is observed in \({\alpha }_{g}\), bubble diameter d, interfacial area a, \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\), indicating that the alteration in the blade curvature has a uniform effect on these variables. This is due to the increase in the curvature of the blade reduced the formation of the trailing vortex at the back of the blade, and the results are consistent with the findings of Jorge et al21. However, with the reduction in blade height in the upper part of the disk, \({\alpha }_{g}\), bubble diameter d, and \({E}_{V}\) initially increase slightly before decreasing, while for interfacial area a and \({k}_{L}a\), there is a continuous decrease, and \(P/V\) shows a linear decrease. Because the high pressure region of the stress on the blade decreases with the decrease of the blade height, the resistance to the blade decreases significantly22. The results show that there is a highly linear relationship between the reduction of blade height and power consumption. When the blade height in the upper part of the disk is reduced from 15 to 10 mm, there is a significant drop in \({\alpha }_{g}\), interfacial area a, and \({k}_{L}a\). The results indicate that a slight asymmetry in the turbine blades on the disk leads to a corresponding improvement in impeller performance, as the reduction in the interaction area between the blade and the fluid correspondingly decreases the power requirement, and the impeller’s gas holding capacity and dispersion ability do not decrease but even show a slight improvement. However, when the turbo impeller blades on the disk exhibit a high degree of asymmetry (T10B20), the impeller performance undergoes a significant decline. This is primarily due to the substantial reduction in gas handling capacity far outweighing the decrease in power input required by the impeller.

The influence of changes in the radial bending angle of the blades on \({\alpha }_{g}\), bubble diameter d, \({k}_{L}a\), and \(P/V\) is consistent with that of coefficient a. However, \({E}_{V}\) initially decrease and then increase, indicating that when the blade is bent slightly in a counterclockwise direction, the decline in gas–liquid mass transfer performance outweighs the reduction in power required by the impeller. When the blade is bent to a certain extent, the impeller’s gas handling capacity becomes stable, and power consumption still linearly decreases, thus leading to a rebound in overall performance. Overall, the degree of upper-lower asymmetry of the blades has the smallest impact on these variables, yet the largest influence on \({E}_{V}\).

Multiple regression analysis

In this paper, we focus on the effect of the change of blade shape on the volumetric oxygen mass transfer coefficient and power consumption per unit volume, for which we fit the quantitative relationship between \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\) and the three factor variables by multiple linear regression, and the results are shown in Table 4 and Eqs. (34), (35).

The regression analysis demonstrated a high overall goodness-of-fit, indicating a strong linear relationship between \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\) with the three factors (A, B, and C). For the \(P/V\) regression model, the \({R}^{2}\) value was 0.968, with an adjusted \({R}^{2}\) of 0.948, an F-statistic of 49.799, and a P-value of 0.000***, confirming the model’s excellent fit and statistical significance. Among the independent variables, coefficient A exhibited the most significant impact on \(P/V\), showing a negative linear relationship, while the effects of asymmetry and radial bending angle were relatively minor. For the \({k}_{L}a\) regression model, the \({R}^{2}\) value was 0.897, with an adjusted \({R}^{2}\) of 0.836, an F-statistic of 14.578, and a P-value of 0.007***, indicating statistical significance. Coefficient A remained the most influential factor on the dependent variable, while the effects of asymmetry and radial bending angle varied. The variance inflation factor (VIF) for all independent variables was 1, confirming the absence of multicollinearity and ensuring the validity of the model and the independence of the independent variables. These results underscore the robustness of the regression models and their suitability for analyzing the relationships between the studied variables.

Range analysis of \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\)

Range analysis was employed to evaluate the influence of control factors on target variables. In this study, an online software tool, SPSSPRO, was employed to conduct range analysis on the pivotal variables of \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\), with the results presented in Table 5. In the evaluation of \({k}_{L}a\), the most significant factor is coefficient a (curvature of the blade), followed by the radial bending angle and the asymmetry of the blade’s upper and lower. The experiment revealed that the maximum \({k}_{L}a\) could be achieved with the blade geometry of P-0.1-T20B20-A0°. Regarding \(P/V\), the influence factors are ranked in the order of the radial bending angle, coefficient a, and the asymmetry of the blade’s upper and lower. The blade shape P-0.2-T10B20-AM30° exhibited the lowest \(P/V\). The asymmetry of the blade’s upper and lower exerts the greatest impact on the \({E}_{V}\), followed by the radial bending angle, while the influence of coefficient a is minimal. The optimal balance between oxygen transfer and power consumption was achieved with a blade geometry of P-0.1-T15B20-AM30°. Given that different production processes have varying requirements for impeller performance, the selection and optimization of impellers should be tailored to the specific production process. In the majority of aerobic fermentation processes, the ideal impeller should provide high oxygen transfer while minimizing input costs to maximize economic returns.

Variance analysis of \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\)

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to determine the significance of the impact of control factors on the target variable. The significance of the influence of control factors on the target variable is assessed through the P-value. A P-value < 0.05 typically indicates a significant difference, whereas a P-value > 0.05 suggests no significant difference. The ANOVA report obtained via the online software SPSSPRO elucidates the effects of control factors on \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\), respectively, as outlined in Table 6.

Coefficient a exhibited a significant influence on \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\) (P-value < 0.05), yet had a non-significant effect on \({E}_{V}\) (P-value > 0.05), due to the consistent trend in the impact of blade curvature alterations on \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\). The asymmetry of the blade exhibits a non-significant impact on \({k}_{L}a\) (P-value = 0.055*), yet significantly affects both \(P/V\) and \({E}_{V}\). Changes in blade height modulate the interaction between the blade and the fluid, thereby significantly impacting power input and altering \({E}_{V}\). The radial bending angle of the blade significantly affects all three target variables, with P-values below 0.05. Additionally, post-hoc multiple comparisons using the LSD method (data not shown) revealed that the optimal impeller shape for high \({k}_{L}a\), low \(P/V\), and high \({E}_{V}\) corresponds to the findings of the range analysis.

For \({E}_{V}\), the selection of the optimal impeller structure hinges on the oxygen transfer requirements and the balance of power consumption within the actual fermentation system. The target function of this study remains valid within the controlled parameters of impeller structural characteristics.

Impeller performance

With the aim of achieving a high \({E}_{V}\), the optimal blade shapes were identified through single-factor experiments and orthogonal experimental design as P-0.15-T15B20-AM15° and P-0.1-T15B20-AM30°, respectively, as shown in Fig. 11.

To investigate the comprehensive performance of the designed impellers, CFD simulations were conducted at varying rotational speeds (100 rpm, 200 rpm, 300 rpm, 400 rpm, 500 rpm) and aeration rates (0 vvm, 0.6 vvm, 1 vvm, 1.4 vvm, 1.8 vvm), and the results were compared with those of the RT and CD-6 impellers. The \({k}_{L}a\), \(P\), and \({E}_{V}\) for the four impellers under different operating conditions were depicted in Fig. 12.

The rotational speed and aeration rate significantly affect \({k}_{L}a\), with an increase in \({k}_{L}a\) observed as the stirring speed and aeration rate rise. Under identical conditions, the RT impeller exhibits a significantly higher \({k}_{L}a\) than the other three types of blades, while the P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° impeller shows a slightly higher \({k}_{L}a\) than the P-0.15-T15B20-AM15° impeller. The RT impeller’s chief merits are its commendable performance in gas–liquid dispersal and its formidable capacity for mass transfer13. In comparison to the RT impeller and the CD-6 impeller, the average \({k}_{L}a\) of the P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° decreased by 47.7% and 31.1%, respectively.

Conventionally, the power consumption of impellers exhibits a trend of increasing with the augmentation of agitation speed and decreasing with the rise in aeration rate. The influence of aeration rate on P is substantially lesser than that of rotational speed, and the degree of variation also depends on the type of impeller. Under aeration conditions, the formation of “gas cavities” in the low-pressure regions of impeller blades due to the accumulation of gas leads to a diminution in the radial pumping capacity and gas dispersal performance of the impellers54. The Relative Power Demand (RPD), which is the ratio of aeration power to non-aeration power, serves as a metric to reflect the impact of low-pressure cavities on gas dispersal performance. A critical flaw of the RT impeller is its substantial decrease in P with increasing aeration rate, which compromises the stability of the gas–liquid system’s operation55. At a rotational speed of 200 rpm and an air velocity of 0.39 m/s, the RPD of the RT impeller dropped to a minimum of 0.69. In contrast, the RPD of the other three impellers remained relatively stable, hovering around 0.95, which was attributed to the larger blade curvature21,54. Overall, the power demand of P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° was slightly lower than that of P-0.15-T15B20-AM15° and significantly lower than that of the RT and CD-6 impellers. The average power demand of P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° is merely 31.2% of that of the RT impeller and 46.1% of that of the CD-6 impeller, thereby indicating that the designed impellers exhibit an exceptional energy-saving efficacy.

Fig. 12(C) illustrates that under most conditions, the \({E}_{V}\) value of P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° exceeds that of P-0.15-T15B20-AM15°, with a markedly higher value than CD-6, and the RT impeller exhibits the lowest value. The P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° impeller exhibited an average \({E}_{V}\) increase of 12.4% and 8% over the RT and CD-6 impellers, respectively. Additionally, it was observed that only under conditions of low rotational speed and elevated aeration rates does the \({E}_{V}\) value of P-0.15-T15B20-AM15° slightly exceed that of P-0.1-T15B20-AM30°. This suggests that the shape configuration of 0.1-AM30° exhibits better performance under most conditions compared to the 0.15-AM15° configuration, making it more suitable for aerobic fermentation processes.

To compare the mass transfer rates of four types of impellers under the same power consumption, we referenced the studies by Xie et al.56 and Pan et al.32, and fitted the empirical correlations for the mass transfer of the impellers, as shown in Eqs. (36)-(39).

The results indicate that the mass transfer rate fits well with the impeller power consumption and superficial gas velocity, and is consistent with the results reported in the literature32,56,57, which further validates the accuracy of our simulation results. Based on the experimental settings of this study, by adjusting the range of rotation speed and aeration ratio, the calculated ranges of the dimensionless constants Reynolds number \(Re\) and Froude number \(Fr\) are 6.67 × 104—3.33 × 105 and 0.056—1.417, respectively. These data indicate that the fluid within the reactor is in a turbulent state, and as the stirring speed increases, the flow state transitions from relatively stable to unstable. Figure 13 shows the power number as a function of Reynolds number for the four impellers. Generally speaking, there is a positive correlation between stirring power criterion and Reynolds number. However, when the turbulent state is reached (Re > 4 × 103), the power number will remain stable, as shown in Fig. 13. Compared to RT and CD-6, there is a significant decrease in the \(Po\) of P-0.15-T15B20-AM15° and P-0.1-T15B20-AM30°due to the increase in blade curvature and the increased bending of the blade reduces the resistance of the fluid acting on the blade19. And the power number of P-0.15-T15B20-AM15°and P-0.1-T15B20-AM30°are basically the same, indicating that the configuration of 0.15-AM15° and 0.1-AM30° has the same effect in reducing power consumption.

To sum up, within the operational scope of this study, the new impeller designed in this paper is suitable for most practical production systems involving gas-filled stirred tanks.

Conclusions

In response to the specific demands of microbial aerobic fermentation processes, this research has employed a methodology synergistically combining CFD with Taguchi’s experimental design strategies to refine the design of the impeller blades within a disc turbine. The focus has been on optimizing the blade’s curvature, the degree of asymmetry, and the radial bend angle, thereby enhancing gas–liquid mass transfer efficiency and concurrently reducing energy consumption. The principal findings of this investigation are summarized as follows:

(1) The optimal combination of control factors is determined as follows: the blade shape P-0.1-T20B20-A0° yields the highest \({k}_{L}a\); the blade shape P-0.2-T10B20-AM30° requires the least \(P/V\); and the blade shape P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° achieves the maximum \({E}_{V}\).

(2) Statistical analysis indicates that the coefficient a significantly influences both \({k}_{L}a\) and \(P/V\), whereas \({E}_{V}\) is not significantly affected. The degree of upper and lower blade asymmetry significantly impacts \(P/V\) and \({E}_{V}\), but not \({k}_{L}a\). The radial bend angle demonstrates a significant impact on \({k}_{L}a\), \(P/V\), and \({E}_{V}\).

(3) Under conditions of 100–500 rpm rotational speeds and 0–1.8 vvm aeration rates, the average power demand of the P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° impeller is merely 31.2% of that for the RT impeller and 46.1% of that for the CD-6 impeller, while the average volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient \({k}_{L}a\) remains at 52.3% of the RT impeller and 68.9% of the CD-6 impeller. The average \({E}_{V}\) values are increased by 12.4% and 8% over the RT and CD-6 impellers, respectively. In most conditions involving rotational speeds and aeration rates, the \({E}_{V}\) value of the P-0.15-T15B20-AM15° impeller exceeds that of the P-0.1-T15B20-AM30° impeller, making it more suitable for energy-efficient production within the aerobic fermentation process.

(4) Based on the findings of this study, insights are provided for the development of novel impeller configurations in bioreactors to promote energy-efficient production in aerobic fermentation processes. The integration of CFD with data-driven approaches represents an emerging direction for the design optimization of bioreactor impellers.

Data availability

Data is included in the article: For further questions, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Lebranchu, A. et al. Impact of shear stress and impeller design on the production of biogas in anaerobic digesters. Bioresour. Technol. 245, 1139–1147 (2017).

Ding, J., Wang, X., Zhou, X.-F., Ren, N.-Q. & Guo, W.-Q. CFD optimization of continuous stirred-tank (CSTR) reactor for biohydrogen production. Bioresour. Technol. 101, 7005–7013 (2010).

Nath, K. & Das, D. Modeling and optimization of fermentative hydrogen production. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 8569–8581 (2011).

Zou, H. et al. Metabolic analysis of efficient methane production from food waste with ethanol pre-fermentation using carbon isotope labeling. Bioresour. Technol. 291, 121849 (2019).

Puligundla, P., Smogrovicova, D., Mok, C. & Obulam, V. S. R. A review of recent advances in high gravity ethanol fermentation. Renewable Energy 133, 1366–1379 (2019).

Pandiyan, K., Singh, A., Singh, S., Saxena, A. K. & Nain, L. Technological interventions for utilization of crop residues and weedy biomass for second generation bio-ethanol production. Renewable Energy 132, 723–741 (2019).

Liu, P. et al. Study on the mass transfer characteristics of gas and liquid phases in a three-layer combined paddle fermenter. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 108791 (2022).

Roman, R. V., Tudose, Z. R., Gavrilescu, M., Cojocaru, M. & Luca, S. Performance of industrial scale bioreactors with modified RUSHTON turbine agitators. Acta Biotechnol. 16, 43–56 (1996).

Humbird, D., Davis, R. & McMillan, J. D. Aeration costs in stirred-tank and bubble column bioreactors. Biochem. Eng. J. 127, 161–166 (2017).

Devi, T. & Kumar, B. CFD simulation of flow patterns in unbaffled stirred tank with CD-6 impeller. CI&CEQ 18, 535–546 (2012).

Park, J., Ahan, W. & Lee, J. W. Effect of multiple impeller designs and configurations on the droplet size and uniformity in a 100 L scale stirred tank. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 38, 1348–1357 (2021).

Lee, S. & Varma, A. Aldol condensation of n-butyraldehyde in a biphasic stirred tank reactor: Experiments and models. AIChE J. 61, 2228–2239 (2015).

Van’t Riet, K. & Smith, J. M. The behaviour of gas—liquid mixtures near Rushton turbine blades. Chem. Eng. Sci. 28, 1031–1037 (1973).

Van’t Riet, K. & Smith, J. M. The trailing vortex system produced by Rushton turbine agitators. Chem. Eng. Sci. 30, 1093–1105 (1975).

Cooke, M. & Heggs, P. J. Advantages of the hollow (concave) turbine for multi-phase agitation under intense operating conditions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 60, 5529–5543 (2005).

Dayton, A. B. ASYMMETRIC CONCAVE BLADES.

Galindo, E. & Nienow, A. W. Performance of the scaba 6SRGT agitator in mixing of simulated xanthan gum broths. Chem. Eng. Technol. 16, 102–108 (1993).

Li, Z., Song, G., Bao, Y. & Gao, Z. Stereo-PIV experiments and large eddy simulations of flow fields in stirred tanks with Rushton and curved-Blade turbines. AIChE J. 59, 3986–4003 (2013).

Jia, Z. et al. CFD simulation of flow and mixing characteristics in a stirred tank agitated by improved disc turbines. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 50, 95–107 (2022).

Zheng, Z., Sun, D., Li, J., Zhan, X. & Gao, M. Improving oxygen transfer efficiency by developing a novel energy-saving impeller. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 130, 199–207 (2018).

Vasconcelos, J. M. T., Orvalho, S. C. P., Rodrigues, A. M. A. F. & Alves, S. S. Effect of blade shape on the performance of six-bladed disk turbine impellers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 39, 203–213 (2000).

Jia, Z. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation of the characteristics of novel disc turbines in aerated stirred tanks. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 9886–9900 (2023).

Gu, D., Wen, L., Xu, H. & Ye, M. Study on hydrodynamics characteristics in a gas-liquid stirred tank with a self-similarity impeller based on CFD-PBM coupled model. J. Tw. Inst. Chem. Eng. 143, 104688 (2023).

Yao, Y., Fringer, O. B. & Criddle, C. S. CFD-accelerated bioreactor optimization: Reducing the hydrodynamic parameter space. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 8, 456–464 (2022).

Zamani Abyaneh, E. et al. Mixing assessment of an industrial anaerobic digestion reactor using CFD. Renewable Energy 192, 537–549 (2022).

Fatahian, E., Mishra, R., Jackson, F. F. & Fatahian, H. Optimization and analysis of self-starting capabilities of vertical axis wind turbine pairs: A CFD-Taguchi approach. Ocean Eng. 302, 117614 (2024).

Shu, L. et al. Process optimization in a stirred tank bioreactor based on CFD-Taguchi method: A case study. J. Cleaner Prod. 230, 1074–1084 (2019).

Xu, C. et al. Power consumption and oxygen transfer optimization for C5 sugar acid production in a gas-liquid stirred tank bioreactor using CFD-Taguchi method. Renewable Energy 212, 430–442 (2023).

Nataraj, M. & Arunachalam, V. P. Optimizing impeller geometry for performance enhancement of a centrifugal pump using the Taguchi quality concept. Proceed. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part A: J. Power Energy 220, 765–782 (2006).

Marchisio, D. L., Pikturna, J. T., Fox, R. O., Vigil, R. D. & Barresi, A. A. Quadrature method of moments for population-balance equations. AIChE J. 49, 1266–1276 (2003).

Imai, Y., Takei, H. & Matsumura, M. A simple Na2SO3 feeding method for K<scp>L</scp>a measurement in large-scale fermentors. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 29, 982–993 (1987).

Pan, A., Xie, M., Xia, J., Chu, J. & Zhuang, Y. Gas-liquid mass transfer studies: The influence of single- and double-impeller configurations in stirred tanks. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 35, 61–72 (2018).

Garcia-Ochoa, F., Gomez, E. & Santos, V. E. Fluid dynamic conditions and oxygen availability effects on microbial cultures in STBR: An overview. Biochem. Eng. J. 164, 107803 (2020).

Mishra, S., Kumar, V., Sarkar, J. & Rathore, A. S. Mixing and mass transfer in production scale mammalian cell culture reactor using coupled CFD-species transport-PBM validation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 267, 118323 (2023).

Zhang, H., Song, N., Yu, T. & Qu, C. Process intensification in gas-liquid mass transfer by modification of reactor design: A review. Energy Tech 11, 2201495 (2023).

Bach, C. et al. Evaluation of mixing and mass transfer in a stirred pilot scale bioreactor utilizing CFD. Chem. Eng. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2017.05.001 (2017).

Chen, M., Wang, J., Zhao, S., Xu, C. & Feng, L. Optimization of dual-impeller configurations in a gas-liquid stirred tank based on computational fluid dynamics and multiobjective evolutionary algorithm. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55, 9054–9063 (2016).

Park, S., Na, J., Kim, M. & Lee, J. M. Multi-objective Bayesian optimization of chemical reactor design using computational fluid dynamics. Comput. Chem. Eng. 119, 25–37 (2018).

Montante, G., Horn, D. & Paglianti, A. Gas–liquid flow and bubble size distribution in stirred tanks. Chem. Eng. Sci. 63, 2107–2118 (2008).

Scargiali, F., D’Orazio, A., Grisafi, F. & Brucato, A. Modelling and simulation of gas-liquid hydrodynamics in mechanically stirred tanks. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 85, 637–646 (2007).

Selma, B., Bannari, R. & Proulx, P. Simulation of bubbly flows: Comparison between direct quadrature method of moments (DQMOM) and method of classes (CM). Chem. Eng. Sci. 65, 1925–1941 (2010).

Liu, Y.-J. et al. γ-CT measurement and CFD simulation of cross section gas holdup distribution in a gas–liquid stirred standard Rushton tank. Chem. Eng. Sci. 66, 3721–3731 (2011).

Abrahamson, J. Fluent Theory Guide. (2021).

Shu, S., Vidal, D., Bertrand, F. & Chaouki, J. Multiscale multiphase phenomena in bubble column reactors: A review. Renewable Energy 141, 613–631 (2019).

Chen, H., Yi, X.-G., Zhang, X.-B. & Luo, Z.-H. CFD-PBM simulation and scale-up of the pilot-scale bioreactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 741–752 (2023).

Prince, M. J. & Blanch, H. W. Bubble coalescence and break-up in air-sparged bubble columns. AIChE J. 36, 1485–1499 (1990).

Luo, H. & Svendsen, H. F. Theoretical model for drop and bubble breakup in turbulent dispersions. AIChE J. 42, 1225–1233 (1996).

Buffo, M. M. et al. Influence of dual-impeller type and configuration on oxygen transfer, power consumption, and shear rate in a stirred tank bioreactor. Biochem. Eng. J. 114, 130–139 (2016).

Ameur, H. Mixing of shear thinning fluids in cylindrical tanks: effect of the impeller blade design and operating conditions. Int. J. Chem. Reactor Eng. 14, 1025–1033 (2016).

Peng, H. Y., Han, Z. D., Liu, H. J., Lin, K. & Lam, H. F. Assessment and optimization of the power performance of twin vertical axis wind turbines via numerical simulations. Renewable Energy 147, 43–54 (2020).

Cheng, B., Du, J. & Yao, Y. Power prediction formula for blade design and optimization of dual darrieus wind turbines based on taguchi method and genetic expression programming model. Renewable Energy 192, 583–605 (2022).

Zhao, J., Gao, Z. & Bao, Y. Effects of the blade shape on the trailing vortices in liquid flow generated by disc turbines. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 19, 232–242 (2011).

Xu, C., Liu, X. & Gu, X. Computational studies of airlift and stirred airlift bioreactors with non-Newtonian fluid: A comparison of hydrodynamics and gas-liquid mass transfer. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 110800 (2023).

Liang, Y. et al. Torque and bending moment acting on a flexible shaft agitated by disk turbines in a gas–liquid stirred vessel. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 27, 781–793 (2019).

Smith, J. M. & Gao, Z. Power demand of gas dispersing impellers under high load conditions. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 79, 575–580 (2001).

Xie, M. et al. Flow pattern, mixing, gas hold-up and mass transfer coefficient of triple-impeller configurations in stirred tank bioreactors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 5941–5953 (2014).

Martín, M., Montes, F. J. & Galán, M. A. Bubbling process in stirred tank reactors II: Agitator effect on the mass transfer rates. Chem. Eng. Sci. 63, 3223–3234 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China [2021YFC2103500], National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 22208099].

Funding

National Key R&D Program of China [2021YFC2103500], National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 22208099].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. SY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. AM: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. JY: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. YZ:Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. CL: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, Q., Yang, S., Mohsin, A. et al. Optimization of oxygen transfer and power consumption in aerobic bioprocess by designing disc turbine impeller based on CFD-Taguchi method. Sci Rep 15, 8102 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92463-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92463-1