Abstract

Bioactive antimicrobial films play important roles in various fields, such as biodegradable interfaces, tissue regeneration, and biomedical applications where preventing infection, biocompatibility, and immune rejection are important. In the present study, bioactive POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene filled PLA composite film was prepared using the solution casting method for biomedical applications. The contact angle tests were investigated to reveal the usability of the thin films in biomedical applications. The angle decreased from 85.92° degrees in pure PLA thin films to 72.23° on POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene films. The antibacterial performance, cytotoxicity and cell viability assessments of the prepared films have also been thoroughly investigated. Antibacterial tests revealed that the POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene films effectively inhibited the growth of E. coli and S. aureus by 65.93% and 80.63%, respectively, within 4 h. These inhibition rates were observed as 58.32% and 54.97% for E. coli and S. aureus, respectively, after 24 h. Cytotoxicity assessments demonstrated that PMPs consistently showed higher cell viability due to the combination of POSS and Ti3C2Tx MXene. The obtained results suggest that the POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene film is a promising candidate in cases where bacterial inhibition and high biocompatibility are of critical importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, various types of antimicrobial hybrid materials have been developed as antibiotic-independent antibacterial agents to overcome the drug resistance issue. In this regard, nanomaterials-filled bioactive antimicrobial films have received intense interest in biomedical applications where infection prevention and antibacterial properties are essential. In biomedical research, it is necessary to balance fighting antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ensuring that the materials used in medical treatments are safe for the body. Materials possessing antibacterial properties are pivotal in preventing infections across various domains, including tissue engineering, wound healing, antimicrobial applications, and implantable medical devices. It is crucial to perform thorough evaluations of the harmful effects of these substances, as some solid antibacterial substances could also have damaging effects on human cells1,2. It is essential for the successful application of engineered biomaterials in clinical settings that they do not cause undesirable side effects.

Viability is the first test that should be performed when evaluating new materials for biomedical applications, as it is an indicator that the tissue response to the material is reliable3,4. For example, silver nanoparticles have been reported in some studies to be effective against various pathogens but can show any adverse effects on human cells. There is still a need to search for materials with low toxicity and high antibacterial properties5,6. For these reasons, researchers are conducting further research by creating hybrid structures with different materials or developing surface modifications of nanoparticles7,8.

The investigation of 2D MXene (Ti3C2Tx in particular) based materials, which provide unique advantages, especially in antibacterial and biocompatibility, has attracted a growing interest in the literature. The 2D lamella structural MXene materials, having a general formula of Mn+1XnTx are derived from MAX (Mn+1AXn) phases by selectively acidic removal of A elements (3A and 4A group elements). Herein, the M represent the transition metals, X refer to the either carbide and/or nitride elements, and Tx is the functional groups of ‒OH, ‒O, ‒F/Cl/S. MXenes are two-dimensional (2D) transition metal carbides and nitrides that exhibit excellent conductivity, hydrophilicity, and large surface area. Recent studies have identified MXenes as highly effective structures that can be used as antibacterial and biomaterials9,10,11. The antibacterial properties of MXenes are attributed to their sharp edges, which damage the cell membrane. This damage results in cytoplasmic contents’ leakage and eventual cell collapse12,13,14. MXene-based composites have been reported in some studies to exhibit high antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, with antibacterial activity exceeding 80% in specific formulations12,15. Antibacterial activity can be improved by modification of the lateral dimension of MXene nanosheets, especially surface functional groups and number of layers16,17. There are studies on the incorporation of MXene into polymer matrices such as polycaprolactone (PCL) and polylactic acid (PLA), where they show enhanced antibacterial activity, and these composites can be used for wound healing applications18,19. Even studies show that MXenes can exhibit selective toxicity against cancer cells while being non-toxic to normal cells at specific concentrations20,21,22. The mechanism of cytotoxicity starts with oxidative stress, resulting in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cell death23,24.

MXene hybrid materials modified with polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) can benefit from the properties of both components. POSS, which belongs to the class of organic–inorganic hybrid compounds, is known for its distinct silicon-oxygen cage-like structure, ensuring biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity. Research has revealed that POSS-modified materials generally exhibit less cytotoxicity than unmodified ones. For instance, hydrogels containing POSS have been reported to show good biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity, making them suitable for drug delivery, gene therapy, and tissue engineering applications25,26. POSS filling into various materials can improve the overall mechanical properties and stability of the materials and also alter their cytotoxicity properties27,28. With the protective effect of hydrophilic components, POSS could be incorporated into the structures of polymers, reducing the toxic effects of cationic chains17. Moreover, researchers have found that adding POSS to polyurethanes enhances biocompatibility without negatively impacting cell viability29. Additionally, there have been reports of thermoplastic starch composites modified with POSS demonstrating notable antibacterial effects against Staphylococcus aureus30.

There are many mechanisms underlying the antibacterial properties of POSS. The interaction of functional groups of POSS with bacterial membranes leads to disruption and subsequent cell death. The antibacterial effects of POSS may be further potentiated by microbial cell interaction provided by various functional groups. However, further research is needed to fully elucidate these mechanisms and utilize POSS in areas such as drug delivery systems or antimicrobial coatings in medical devices25.

By incorporating POSS, which exhibits a biocompatible and low-toxicity structure, the antibacterial activity of MXenes can be increased31,32. POSS structures enabling MXenes to be modified with different functional groups and increase their antibacterial properties will allow development in this field since they will not increase toxicity33. The production of hybrid materials such as POSS and MXenes can combine the properties of both materials and show a higher synergistic effect.

As summarized above, antibacterial properties of MXene and POSS-based materials have been reported. However, combinations of these two unique materials have not yet been investigated for antibacterial and other applications. In this study, bioactive POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene-filled PLA hybrid film was prepared and its antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus and cytotoxic effects on L929 cell line were investigated, highlighting its application potential such as infected wound treatment and antibacterial applications. Schematic representation of the fabrication process and antibacterial activity mechanism of the POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene-filled PLA film is shown in Fig. 1.

Results and discussion

Characterization

The morphological, structural and crystal structures of POSS nanoparticles doped Ti3C2Tx MXene sheets were observed in SEM and HRTEM images. In top-down intercalation and delamination methods, the MXene phases can be obtained by chemical or electrochemical etching of MAX phases. Considering MAX phases as starting material, the acidic exfoliation reactions for selective removal of group A element and formation of functional groups (Tx = –F, =O or –OH) can be described by the following equations (Eqs. 1–3)34,35:

The above consecutive acidic reactions represent the formation of 2D Ti3C2 with the surface termination group Tx (–F, =O or –OH). The laterally oriented accordion-like 2D Ti3C2Tx layers were obtained after selective etching of Al (A group) element from the Ti3C2Tx MAX phase. The lamellar structural characteristic of the Ti3C2Tx MXene phase is observed in Fig. 2a, b. The presence of nano-sized POSS particles is seen as white dots in the 2D Ti3C2Tx layers (Fig. 2c, d). The cross-section SEM images of P film were also taken to observe the dispersion of POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene into the PLA matrix (Fig. 2e, f). Coarse Ti3C2Tx MXene particles were successfully embedded in PLA and distributed uniformly.

The 1H-NMR peaks matched well with the reactive groups of POSS nanoparticles, confirming their successful preparation (Fig. 3a). The elemental EDX mapping images of POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene nanoparticles were evaluated for the Ti, O, C, and Si elements (Fig. 3b–f). The presence of Ti, O, and C is associated with Ti3C2Tx MXene, while the homogeneous distribution of Si confirms the presence of POSS nanoparticles on the MXene surface.

The crystal and morphological structure of PMPs thin films were further analyzed by high-resolution transmission electron microscope images (HRTEM) and selected area (electron) diffraction (SAED) patterns36,37. The corresponding SAED patterns of Ti3C2Tx layers displays hexagonal diffraction rings, which are indexed to the [\(10\overline{1 }2\)], [\(2\overline{11 }0\)], [\(20\overline{2 }2\)], [\(20\overline{2 }10\)], and [\(3\overline{12 }7\)] planes (Fig. 4a). The interplanar atomic d-spacing of 0.320 nm is assigned to the [0001] crystal plane of the Ti3C2Tx layer (Fig. 4d), while 0.212 nm and 0.349 nm correspond to the [10,11,12,13,14] and [0004] crystal planes of the Ti3C2Tx, respectively (Fig. 4b). POSS nanoparticles covered the surface of Ti3C2Tx layers as an amorphous film with an average thickness of 20 nm (Fig. 4c).

XRD analysis results confirmed that the structures contributed as fillers within PLA corresponded related peaks (Fig. 5a). Characteristic sharp PLA peaks were detected at 16.21, 19.83, and 22.51 2θ degrees38. Normally, the XRD peaks of PLA thin films are detected in the broad spectrum range of 10–20 2θ degrees39, while the sharp peaks observed in the synthesized films are thought to be a result of the increased thickness of the film. Major Ti3C2Tx MXene peaks was detected in PM films at 35.67, 41.56, and 61.32 2θ degrees with (001), (015), and (110) planes, respectively40,41. Due to the significantly high amount of PLA used compared to POSS, the characteristic peaks of POSS, which does not have a highly crystalline structure, were suppressed but could still be detected at 23.24 and 36.41 2θ degrees42,43.

The bond types of PLA and the incorporation of POSS nanoparticles into PLA and MXene structures were confirmed by FTIR analysis (Fig. 5b). In the pure PLA film, the peaks appeared at the 3000–2750 cm−1, 1752 cm−1, 1420 cm−1, 1360 cm−1, 1210 cm−1, and 1085 cm−1 corresponds to the weak stretching vibration of ‒C‒H, the strong stretching vibration of ‒C=O, the medium stretching and bending vibration of ‒CH3, the strong bending vibration of ‒CH, and the strong stretching vibration of COC, respectively44. On the other hand, no different band structure is observed in the PM film, which is due to the nonpolymeric structure of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Furthermore, with the presence of POSS nanoparticles in the PMPs, weak C‒H, Si‒O‒Si, and Si‒O stretching bonds were observed at 1232 cm−1, 118 cm−1, and 842 cm−1 wavenumbers, respectively45.

The termination group of MXene surfaces (Tx) varies according to the etching types (HCL, HCL‒LiF, HF). XPS analysis was performed to further investigate the electronic structure, termination groups and elemental composition of PMPs thin films and the results are given in Fig. 5c–f. The high-resolution XPS spectra of Ti 2p in Fig. 5c displayed two major peaks at 459.28 eV and 465.08 eV belonging to Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 (TiCxOy), respectively (Fig. 5c). After deconvolution of Ti 2p main peaks, three sub-peaks appeared at 454.58 eV, 455.98 eV, and 461.88 eV are assigned to Ti‒C‒Tx, Ti‒O 2p3/2 and Ti-C‒Tx peaks, respectively. The peaks assigned to Ti‒C‒Tx are related to the surface termination groups of –OH and –F46. The presence of POSS on the Ti3C2Tx layers were also investigated by XPS analysis (Fig. 5d). The Si 2p peaks at 100.1 eV and 104.7 eV correspond to the siloxane (SiOx) and silica (Si–O) components of POSS, respectively47. The C1s XPS spectra displayed a major peak and three deconvoluted peaks at 281.38 eV, 284.68 eV, 286.48 eV, and 287.98 eV, which are assigned to C‒Ti, C‒C, C=C, and O‒C=O bonds, respectively (Fig. 5e). The O 1s XPS spectra peaks are located at 530.28 eV, 531.78 eV, and 532.88 eV, belonging to C‒Ti‒Ox, C‒Ti(OH)x, and C‒Ti‒O bonds, respectively. The C‒Ti‒Ox and C‒Ti(OH)x compounds proves the formation of Ti3C2Tx terminal groups (Fig. 5f).

Contact angle measurement results of thin films were given in Fig. 6. The contact angles obtained for the films P, PM, and PMPs were 85.92°, 85.61°, and 72.23°, respectively. (Fig. 6a–c). As is known, the behavior of a material considered for use as a biomaterial in contact with surrounding tissues within the body is of great importance. The behavior of the biomaterial within the body can be bioactive or bioinert. After conducting a contact angle test to reveal these two behaviors, when Ti3C2Tx MXene was filled into the PLA-based thin film, the contact angle decreased from 85.92° to 85.61° (Fig. 6b). The reason for these decreases being minimal compared to the pure PLA thin film is thought to be due to the carbide-based lubricating effect of the Ti3C2Tx MXene structures48. Moreover, the fact that thin films were not applied as a coating on any metal surface is also thought to be a reason why the contact angle values were not affected after the Ti3C2Tx MXene structures were covered by PLA, preventing contact with the liquid. On the other hand, contact angles of PLA-based hybrid thin films decreased to 72.23° with the addition of PMPs thin films (Fig. 6c). It is thought that this decrease is due to the POSS doped between the accordion-like Ti3C2Tx MXene. Indeed, it is anticipated that the presence of C‒H, Si‒O‒Si, and Si‒O stretching bands in the PMPs may cause POSS to separate from the Ti3C2Tx MXene (during the magnetic stirring phase) and bond with PLA, thereby affecting the structure of PLA49. On the other hand, it is thought that the POSS particles separating from the accordion-shaped Ti3C2Tx MXene may have caused micron-sized protrusions on the PLA thin films, resulting in a decrease in the contact angle50. Surface wettability is one of the expected key properties for a biomaterial candidate to exhibit the desired biological response. It’s known that the surfaces exhibiting hydrophilic properties are crucial in enhancing their biocompatibility. Therefore, it has been determined that the decreasing of the contact angle (72.23°) in particular with the PMP film is effective in directly influencing the film’s biological and antibacterial properties. Moreover, researchers have stated that polymers exhibiting hydrophilic character improve cell adhesion by reducing protein adsorption on surfaces and create favourable conditions for cells51.

Viability and antibacterial responses

The antibacterial activities of prepared films (P, PM, and PMPs) against Gram-negative bacterium E. coli and Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus were determined by two methods including the bacteria colony counting technique and measuring optical density of the bacterial suspensions with P, PM and PMPs films at 600 nm wavelength using Thermo Scientific SPECTRONIC 200 UV–Vis spectrometer52. The pure PLA films displayed negligible inhibition effect against S. aureus and E. coli, while PM and PMP films contained less bacteria compared to pure PLA (P) due to the physical damage of MXene and POSS on the bacterial cell membranes (Fig. 7). The 2D sharp edge of Ti3C2Tx and the hybrid networks of POSS can be considered as the most important reasons for the increase in antibacterial activities53,54.

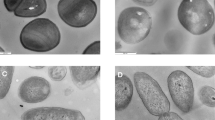

The surface SEM images of P, PM, and PMPs kept for 24 h in the bacterial suspensions were also evaluated for further investigation of physical damage and cell integrity (Fig. 8). The results revealed that E. coli and S. aureus maintained their characteristic undamaged, smooth, rod-like and spherical morphologies with intact cell walls following exposure to pure PLA (P) films. In contrast, significant structural changes were observed in bacterial cells exposed to PM and PMPs films. The structure of cell walls of both E. coli and S. aureus appeared wrinkled and visibly damaged, indicating a disruption of cell integrity. These morphological alterations strongly correlated with the observed reduction in bacterial colony counts, highlighting the antimicrobial efficacy of the PM and PMPs films.

The bacterial viability of Gram-negative (−) bacterium E. coli and Gram-positive (+) bacterium S. aureus exposed P, PM, PMPs films is given in Fig. 9a, b. It is remarkable that PM (PLA/Ti3C2Tx) and PMPs (PLA/Ti3C2Tx/POSS) groups caused a significant decreases in cell viability for the 4 h. The bacterial viability results of PM and PMPs show that the prepared Ti3C2Tx/POSS particles are more dominant and destructive against Gram-positive (+) bacteria S. aureus compared to Gram-negative (−) bacteria E. coli, which is due to the higher negatively charged surface of Gram-positive (+) bacteria S. aureus15.

Antibacterial performance and bacterial inhibition rates of PLA (P), PM, and PMPs thin films against E. coli and S. aureus. (a, b) Bacterial viability (%) of E. coli and S. aureus over different contact times. (c, d) Colony-forming units (CFU/mL) of E. coli and S. aureus at various contact times, demonstrating the antibacterial efficacy of PMPs compared to PLA (P) and PM. Statistical significance: p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and not significant (ns). (e, f) Optical density (OD600) measurements for the growth kinetics of E. coli and S. aureus, showing inhibited growth in the presence of PMPs. (g) Bacterial inhibition (%) of E. coli and S. aureus in contact with PLA (P), PM, and PMPs surfaces after 24 h.

The colony forming units (CFU) curves of P, PM, and PMPs against the E. coli (gram-negative) and S. aureus (gram-positive) for 24 h contact times are given in Fig. 9c, d. Overall, the CFU counts against S. aureus have increased with increasing contact times for control P group, while it showed a fluctuating trend without a static increase with time against E. coli (gram-negative). Combining POSS and Ti3C2Tx resulted in a significant decrease in the CFU counts compared with the P and PM groups against both S. aureus (gram-positive) and E. coli (gram-negative). Significant reductions in CFU count against S. aureus were achieved in the PM and PMPs groups within 4–16 h compared to P group. However, the CFU counts have increased obviously at 24 h for all test groups.

The percentage viability and CFU values exhibit a strong correlation, highlighting the antibacterial effects of the PM and PMPs films compared to the control PLA surface. In the case of E. coli cells, the viability was reduced to 51.75% in the PM group compared to the control PLA film surface within the first 4 h, while in the PMPs group, a more pronounced reduction of 65.93% was observed. By the 8 h mark, cell viability in the PM group showed a reduction of 39.1%, whereas in the PMPs group, viability decreased by 68.22% compared to the P. At 16 h, the PM group exhibited a 35% reduction in viability relative to the control, while the PMPs group demonstrated a more substantial decrease of 61%. By the end of the 24 h period, the viability reduction in the PM group was recorded at 32.23%, whereas the PMPs group showed a significant reduction of 58.32%.

For S. aureus cells, the viability decreased by 63.33% in the PM group and 80.63% in the PMPs group compared to the control within the first 4 h. Over the 8 h timeframe, cell viability decreased by 46.74% in the PM group and 83.18% in the PMPs group compared to the control. By the 16 h mark, the PM group showed a 53.33% reduction in viability, while the PMPs group demonstrated a dramatic decrease of 91.84%. At the end of the 24 h period, cell viability decreased by 20.61% in the PM group and 54.97% in the PMPs group relative to the control.

The optical density (OD₆₀₀) curves of E. coli and S. aureus in the range of 4 h to 24 h show the bacterial growth kinetics variations (Fig. 9e, f). Pure PLA (P) film showed higher bacterial densities for E. coli between 4 to 24 h and reached the highest absorbance intensity at 24 h, while PM and PMPs fluctuated at low absorbance intensities between 4 to 16 h and tended to increase between 16 and 24 h. Based on time period the optical density can be evaluated at three stages of the early growth phase (0–4 h), logarithmic growth phase (4–8 h), and stationary phase (8–24 h).

At the initial time point (0 h), all films exhibited the same OD600 value (0.0850), confirming equivalent bacterial inoculum across all samples. However, the growth inhibition effects varied significantly over time. The PM and PMPs films exhibited substantially lower OD600 values (0.2959 and 0.1320, respectively) compared to the pure PLA film (0.3813) at the 4th hour. This early-stage inhibition suggests that both Ti3C2Tx MXene and POSS contribute to the suppression of bacterial proliferation, with POSS enhancing this effect more prominently. The OD600 values of P, PM, and PMPs were recorded as 0.5630, 0.4257, and 0.3939, respectively at the 8th hour. While all films allowed bacterial growth, the PMPs group maintained the lowest OD600 value. The PM group also displayed intermediate activity, confirming the partial contribution of Ti3C2Tx to antibacterial effects, likely due to its unique two-dimensional structure, surface chemistry, and interaction with bacterial membranes. The differences between the films became more pronounced at the 16th and 24th hours. The PMPs group consistently showed the lowest bacterial density (OD600 = 0.4177 at the 16th hour and 0.6300 at the 24th hour), outperforming both P and PM groups. The PM film demonstrated moderate inhibition (OD600 = 0.4807 at the 16th hour and 0.6356 at the 24th hour), while the PLA film exhibited the highest bacterial growth (OD600 = 0.6523 at the 16th hour and 0.7034 at the 24th hour).

The differences in antibacterial effects between E. coli and S. aureus are evident from the percentage inhibition and CFU data are given in Fig. 9g. In the PM group, E. coli viability decreased by 32.18%, while S. aureus showed a similar reduction of 30.6% compared to the control. For the PMPs group, E. coli viability was reduced by 58.36%, while S. aureus demonstrated a slightly higher reduction of 61.06%, consistent with CFU trends. This difference can be attributed to the thicker peptidoglycan layer of S. aureus, which enhances its interaction with POSS’s functional groups, resulting in greater susceptibility.

The model Gram-negative bacterium E. coli and the model Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus exhibit markedly distinct growth and resistance behaviors due to structural differences in their peptidoglycan layers15. The thicker peptidoglycan layer of S. aureus enables it to proliferate more rapidly than E. coli during the initial hours following exposure to the tested surfaces, which suggests a greater potential for resistance against these materials. However, at the 4 h observation point, surfaces modified with POSS exhibited significantly enhanced antimicrobial efficacy against S. aureus compared to those incorporating Ti3C2Tx MXene. These findings emphasize the pivotal role of material composition and surface chemistry in regulating bacterial resistance mechanisms, thereby underscoring the beneficial impact of POSS in the design of antimicrobial surfaces.

MTT assay and biocompatibility

The prepared PLA (P), PM, and PMPs thin films were diluted in the range of 200% to 25% with a fresh medium for 24 h and 48 h, and the viability of mouse fibroblast cells (L929) was measured at these concentrations (Fig. 10). L929 cells treated with prepared films at concentrations between 200 and 50% dilution rates for 24 h exhibited no significant cytotoxic effects compared to the control group. For PM, cell viability at 200% diluted concentration was 83.00%, gradually decreasing to 37.70% at 25% diluted concentration. For PMPs, cell viability remained relatively high, ranging from 90.70% at 200% diluted concentration to 22.10% at 25% diluted concentration. Notably, the cell viability was considerably higher in the PMPs group, particularly at lower concentrations, indicating a potential enhancement in biocompatibility due to the inclusion of POSS nanoparticles. However, at 25% diluted concentration, both groups exhibited a substantial reduction in cell viability, suggesting that higher concentrations of the materials led to cytotoxicity.

Cell viability of prepared PM and PMPs thin films. Cell viability results are reported as percentages relative to the untreated control group. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) calculated from three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s multiple range tests, where ns: not statistically significant, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001 indicate significant differences between the control and other groups.

Concentration-dependent cytotoxic effects were more pronounced at the 48-h time point. The cell viability of PM ranged from 51.10% at 200% diluted concentration to 31.40% at 25% diluted concentration, while for PMPs this rate varied from 69.50% at 200% diluted concentration to 19.50% at 25% diluted concentration. The increased cell viability observed in the PMPs group at the lower concentrations of 200−50% diluted concentration rates further supports the idea that POSS nanoparticles play a crucial role in enhancing material biocompatibility. This suggests that the incorporation of POSS nanoparticles with Ti3C2Tx MXene promotes more favourable cell-material interactions and may contribute to improving the overall biological performance of the material, especially in biomedical applications. In conclusion, the findings indicate that while both PM and PMPs groups exhibit acceptable biocompatibility at lower concentrations, the addition of POSS nanoparticles in the PMPs group significantly improves cell viability, suggesting a beneficial effect on biocompatibility.

The above data and results proved the effective antimicrobial activity of POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene film (PMPs). The multi sharp layers of MXene were found to act as multi "nano-knife" that lead to physical stresses and disruption of bacterial cells. Moreover, the better antimicrobial activities of PMs and PMPs can be attributed to the functional groups (Tx = –F, =O or –OH) of Ti3C2Tx and the hybrid networks of POSS destroying bacterial cell walls. However, the increase in absorbance intensity can be explained by the thickening of the bacterial cell wall, making E. coli difficult to be punctured by the sharp edge of Ti3C2Tx55,55. The combination of Ti3C2Tx MXene and POSS in the PMPs film demonstrates a synergistic effect, resulting in superior antibacterial activity. Overall, the PMPs film exhibits the highest antibacterial efficacy and improves cell viability, suggesting its potential for applications where bacterial inhibition and high biocompatibility are critical, such as biomedical implants, tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and antimicrobial coatings.

Conclusions

In this study, POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene thin films were successfully prepared using the solution casting method, and their biomedical applications, such as cell viability and antibacterial activities, were investigated. The presence of the POSS and Ti3C2Tx MXene in the prepared films was confirmed by the advanced characterizations methods. The contact angle tests revealed that the surface wettability properties increased with the filler materials. The good antibacterial properties were obtained by the incorporation of POSS nanoparticles and Ti3C2Tx MXene. The cell viability of E. coli (Gram-negative) and S. aureus (Gram-positive) bacteria significantly decreased, and their morphologies were found to be severely damaged in the PM and PMPs films due to sharp edges of Ti3C2Tx MXene and hybrid networks groups of POSS. The results proved that POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene thin films can be safely used in various fields such as wound dressings, antimicrobial coatings, and implantable medical devices, thus positioning them as a promising new type of candidate for advanced biomedical applications.

Materials and methods

Synthesize of Ti3C2Tx MXene and POSS

Zirconia balls and stainless-steel jars were used in a high-energy MITR ball milling machine (Model YXQM-4L) to prepare Ti3AlC2 MAX powders. Initially, 325-mesh titanium (Ti, 99.9% pure, Nanografi) and 325-mesh titanium carbide (TiC, 99.9% pure, Nanografi) and 200-mesh aluminum powder (Al, 99.9% pure, Nanografi) powders were ball-milled using zirconia balls at 350 rpm for 16 h in a molar ratio of 1:2:1, respectively. To improve the interaction between the particles, the ball-milled powders were then cold-pressed at 23 GPa. The cold-pressed powders were calcined for 4 h at 1400 °C in an atmosphere-controlled tube furnace under argon (Ar) gas protection to prevent any oxidation of raw powders and then cooled to room temperature at a ramp temperature of 1 °C s−1. To create consistent, tiny particles, the resulting powders were ball milled for 3 h at 450 rpm. The preparation of MXene derived from MAX phases have been reported in previous studies41,48,56. First, the prepared Ti3AlC2 MAX phases (3 g) were slowly added to the 50 mL of a 1:2 deionized water (DI) and hydrofluoric acid (HF, 49%) solutions under magnetic stirrer at 65 °C for 15 h. Then, the solution was washed and centrifuged several times at 12,000 rpm to eliminate any dissolved fluorides. The Ti3C2Tx MXene precipitates were then placed in a vacuum oven set at 70 °C for 12 h.

For the synthesis of Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane (POSS) nanoparticles, 100 mL methanol (99.9%, HPLC grade), 3.75 mL (3-Aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES, 99%, Liquid), and 7.50 mL hydrochloric acid (37%, solution) were mixed under magnetic stirrer for 18 h at a constant temperature of 90 °C. And then, the solution was cooled down to room temperature, and 100 mL of Tetrahydrofuran (THF, ≥ 99.9%, anhydrous) was poured into the solution to obtain white precipitates. Finally, the white precipitates were washed several times with THF, and the obtained POSS were dried in an oven at 30 ℃.

POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene-filled PLA film

In the production of PLA-based thin films, a similar approach to previous PLA-based coating studies has been followed39,57,58. Accordingly, a PLA/chloroform solution in a 1/10 (wt%/vol) ratio was prepared to achieve the optimum viscosity. PLA was dissolved in chloroform with a magnetic stirrer (HS1-A, LABTron) for 45 min for the production of PLA (abbreviated as P) thin films. For the preparation of PLA-Ti3C2Tx MXene thin films (abbreviated as PM), 1 g of Ti3C2Tx MXene was added to dissolved 40 mL of PLA and mixed using a magnetic stirrer for 30 min and then homogenized for 5 min using an ultrasonic homogenizer (MSK-USP-3N, MTI) at 60% power duty, ensuring the dispersion of Ti3C2Tx MXene particles. For the preparation of POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene-filled PLA (PMPs) thin films, the initially prepared Ti3C2Tx MXene and POSS particles were combined with a ratio of 10/1 (wt%) under a magnetic stirrer for 5 h in a 10 mL ethanol solution. POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene solution was then centrifuged and dried at 40 °C. Finally, the same steps above were followed by adding 1 g of POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene particles to 40 mL of dissolved PLA solution and the production of POSS-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene filled PLA (PMPs) thin films was achieved.

Characterization

The structural, crystallographic, and morphological characterizations of the prepared particles and thin films were identified using the X-ray diffractometer, XRD (Ultima-IV model of Rigaku brand) with Cu-Kα at 20 mA and 30 kV, Field Emission Scanning Electron, FESEM (Sigma 300 model of Zeiss brand) and high-resolution transmission electron, HRTEM HRTEM (2100 model of JEOL). The energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) detector (Ametek, EDAX) was used to gather X-ray scatterings for elemental analysis. The functional surface groups and area of prepared particles were determined using the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, XPS (K Alpha model of Thermo Scientific brand), and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller, BET (Tristar II model of Micromeritics brand) instruments. C‒, H‒, and O‒ bonds in the composite/hybrid films were identified using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet 6700). The nuclear magnetic resonance peaks of prepared POSS were obtained using Agilent 400 NMR experiments 1H carrier frequency of 400.13 MHz.

Contact angle measurements were performed to evaluate the bioactive and bioinert behavior of the prepared film under possible physiological conditions with using the sessile drop technique (Theta Flex, Biolin Scientific). The simulated body fluid (SBF) was prepared using 8 g of NaCl, 400 mg of KCl, 140 mg of CaCl2, 100 mg of MgSO₄·7H2O, 100 mg of MgCl2·6H2O, 60 mg of Na2HPO₄·2H2O, 60 mg of KH2PO₄, 1 g of D-glucose, and 350 mg of NaHCO₃. A 5 μL droplet of SBF was placed at a distance of 10 mm from the thin film surfaces and left at room temperature for 5 s. The resulting contact angle measurements were used to assess the surface wettability characteristics of the thin films.

Cell viability and antibacterial responses

The antibacterial activity of PLA (P), PM, and PMPs films was tested using E. coli and S. aureus as representative Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial models, respectively. Cryopreserved bacterial stocks were employed to initiate overnight cultures in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth, maintained at 37 °C under shaking conditions. Subsequently, 1 mL aliquots of these cultures were sub-cultured and harvested during the logarithmic growth phase to ensure maximum cellular activity. The bacterial suspensions were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min, and the resulting pellets were meticulously washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to eliminate residual metabolites and medium components. The washed bacterial cells were re-suspended in sterile PBS and adjusted to a standardized density of approximately 107 CFU/mL, ensuring uniformity for subsequent antimicrobial assays.

To investigate the antibacterial activity of the membranes (1 cm2), PLA and the modified thin films (PM and PMPs) with dimensions of 1.5 cm in length, 0.66 cm in width, and a surface area of 1 cm² were used. Each surface was exposed to UV sterilization at a wavelength of 254 nm for 15 min before the films were immersed in the bacterial suspension. A negative control with bacteria without any membrane and a positive control with bacteria and unmodified PLA membrane in PBS were included in the assays. To evaluate the effect of contact time on bactericidal activity, membranes were removed at intervals of 4, 8, 16 and 24 h, gently rinsed with saline to remove loosely adherent bacteria, and transferred to 2 mL of PBS. The membranes were then sonicated for 3 min to dislodge bacteria from the surfaces.

Bacterial viability was determined by plating 100 µL of the resulting suspension onto nutrient agar plates and counting the colony-forming units (CFU) after incubating overnight at 37 °C. All experiments were performed in triplicate and the values were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Cell viability was quantified using the following equation (Eq. 4).

Herein, Nc and Nm represent the number of bacterial colonies exposed to the control surface (PLA) and the modified surfaces (PM and PMPs), respectively, for a specified treatment duration.

Cytotoxicity analysis

The biocompatibility of the developed PM and PMPs thin films was evaluated using the MTT assay to determine their effects on the viability of L929 fibroblast cells (Cat. No. M2267, Cell Biologics)59. L929 cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM and DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The cells were maintained under standard conditions of 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

For the assay, L929 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well in 150 µL of growth medium and allowed to adhere for 24 h. The prepared thin films were dissolved in chloroform at different concentrations and diluted in culture medium (from 200 to 25%). Then, the cells were treated with the film solutions at these different concentrations for 5 min. After 24 and 48 h of incubation, 20 µL of 5 mg/mL MTT solution in PBS was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 4 h at 37 °C.

The medium and MTT solution were removed, and 150 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well to solubilize the formazan crystals. The absorbance of the resulting purple solution was measured at 560 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (Epoch, Biotech), with blank corrections subtracted. Cell viability was calculated using the following formula (Eq. 4), with untreated cells as the control.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10.4.1 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Observation of bacterial cells with SEM

SEM analysis was conducted to examine the impact of Ti3C2Tx MXene and POSS on the morphology of bacterial cells using FESEM (Zeiss Sigma 300). SEM imaging performed as follows: after the antibacterial experiments, bacterial cells attached to the surfaces of P thin films, as well as PM and PMPs thin films, were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 4 h at 4 °C. The samples were subsequently rinsed with 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) and subjected to a dehydrated through an ethanol gradient (30, 50, 70, 90, and 100%). Once fully dried at room temperature, the samples were coated with a 5 nm gold layer using a sputter coater before SEM imaging.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of bacterial viability tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.4.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Data normality was determined by descriptive statistics based on mean ± standard deviation using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Inter-group comparisons were performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-hoc test. The results were deemed statistically significant when the p-values were less than 0.05, with a confidence interval of 95%, (n = 3).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hamidian, M. et al. The comparative perspective of phytochemistry and biological properties of the Apiaceae family plants. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–19 (2023).

Roth, A. et al. Wearable adjunct ozone and antibiotic therapy system for treatment of Gram-negative dermal bacterial infection. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–14 (2022).

Serginay, N. et al. Antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity of bioinspired poly(L-DOPA)-mediated silver nanostructure-decorated titanium dioxide nanowires. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 639, 128350 (2022).

Darpentigny, C. et al. Antibacterial cellulose nanopapers via aminosilane grafting in supercritical carbon dioxide. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 8402–8413 (2020).

Machková, A. et al. Silver nanoparticles with plasma-polymerized hexamethyldisiloxane coating on 3D printed substrates are non-cytotoxic and effective against respiratory pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1–11 (2023).

Li, G., Zhang, D. & Qin, S. Preparation and performance of antibacterial polyvinyl alcohol/polyethylene glycol/chitosan hydrogels containing silver chloride nanoparticles via one-step method. Nanomaterials 9, 972 (2019).

Ma, S., Zhan, S., Jia, Y. & Zhou, Q. Superior antibacterial activity of Fe3O4–TiO2 nanosheets under solar light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 21875–21883 (2015).

Sun, D. et al. An investigation of the antibacterial ability and cytotoxicity of a novel cu-bearing 317L stainless steel. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–13 (2016).

Seidi, F. et al. MXenes antibacterial properties and applications: A review and perspective. Small 19, 1007–1020 (2023).

Parajuli, D. et al. Advancements in MXene-polymer nanocomposites in energy storage and biomedical applications. Polymers (Basel) 14, 1–41 (2022).

Lai, X. et al. Multifunctional MXene nanosheets and their applications in antibacterial therapy. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 4, 1–19 (2024).

Zhang, H., Lan, D., Li, X., Li, Z. & Dai, F. Conductive and antibacterial scaffold with rapid crimping property for application prospect in repair of peripheral nerve injury. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 140, 25 (2023).

Zizhou, R., Baratchi, S., Khoshmanesh, K., Wang, X. & Houshyar, S. PMMA/PDMS/MXene nanofibers for postsurgery monitoring of vascular implants. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 9757–9767 (2024).

Arabi Shamsabadi, A., Sharifian, G. M., Anasori, B. & Soroush, M. Antimicrobial mode-of-action of colloidal Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanosheets. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 16586–16596 (2018).

Rasool, K. et al. Antibacterial activity of Ti3C2Tx MXene. ACS Nano 10, 3674–3684 (2016).

Rasool, K. et al. Efficient antibacterial membrane based on two-dimensional Ti3C2Tx (MXene) nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–11 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Flexible wound patches based on MXene/quercetin-waterborne polyurethane composites. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 15786–15797 (2024).

Diedkova, K. et al. Polycaprolactone–MXene nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c22780 (2023).

Santos, X. et al. Antibacterial capability of MXene (Ti3C2Tx) to produce PLA active contact surfaces for food packaging applications. Membranes (Basel) 12, 1146 (2022).

Wu, J., Yu, Y. & Su, G. Safety assessment of 2D MXenes: In vitro and in vivo. Nanomaterials 12, 828 (2022).

Wu, W. et al. Evaluating the cytotoxicity of Ti3C2 MXene to neural stem cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 33, 2953–2962 (2020).

Seitak, A. et al. 2D MXenes for controlled releases of therapeutic proteins. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 111, 514–526 (2023).

Rashid, B. et al. A comparative study of cytotoxicity of PPG and PEG surface-modified 2-D Ti3C2 MXene flakes on human cancer cells and their photothermal response. Materials (Basel) 14, 4370 (2021).

Szuplewska, A. et al. Multilayered stable 2D nano-sheets of Ti2NTx MXene: Synthesis, characterization, and anticancer activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 17, 1–14 (2019).

Arsalani, N. et al. Synthesis of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane nano-crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol)-based hybrid hydrogels for drug delivery and antibacterial activity. Polym. Int. 68, 667–674 (2019).

Laganà, A. et al. Promising materials in the fight against healthcare-associated infections: Antibacterial properties of chitosan-polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes hybrid hydrogels. J. Funct. Biomater. 14, 1–15 (2023).

Jiao, J., Lv, P., Wang, L., Cai, Y. & Liu, P. The effects of structure of POSS on the properties of POSS/PMMA hybrid materials. Polym. Eng. Sci. 55, 565–572 (2015).

Ozdogan, R., Daglar, O., Durmaz, H. & Tasdelen, M. A. Aliphatic polyester/polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes hybrid networks via copper-free 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition click reaction. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 57, 2222–2227 (2019).

Zaredar, Z., Askari, F. & Shokrolahi, P. Polyurethane synthesis for vascular application. Prog. Biomater. 7, 269–278 (2018).

Venkatesan, R. et al. Thermoplastic starch composites reinforced with functionalized POSS: Fabrication, characterization, and evolution of mechanical, thermal and biological activities. Antibiotics 11, 1425 (2022).

Tie, D. et al. Antibacterial biodegradable Mg-Ag alloys. Eur. Cells Mater. 25, 284–298 (2013).

Che Hashim, N. Graphene oxide-modified hydroxyapatite nanocomposites in biomedical applications: A review. Ceram. Silikaty 63, 426–448 (2019).

Toro, R. G. et al. Evaluation of long-lasting antibacterial properties and cytotoxic behavior of functionalized silver-nanocellulose composite. Materials (Basel). 14, 4198 (2021).

Bharali, L., Kalita, J. & Sankar Dhar, S. Several fundamental aspects of MXene: Synthesis and their applications. ChemistrySelect 8, 1–12 (2023).

Naguib, M. et al. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 23, 4248–4253 (2011).

Liao, L. et al. The role of alkali cation intercalates on the electrochemical characteristics of Nb2CTX MXene for energy storage. Chem. A Eur. J. 27, 13235–13241 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Hierarchical Ti3C2Tx MXene/carbon nanotubes hollow microsphere with confined magnetic nanospheres for broadband microwave absorption. Small 18, 1–10 (2022).

Tripathi, N., Misra, M. & Mohanty, A. K. Durable polylactic acid (PLA)-based sustainable engineered blends and biocomposites: Recent developments, challenges, and opportunities. ACS Eng. Au 1, 7–38 (2021).

Topuz, M. Investigation of halloysite nanotube effect in poly-(lactic acid)/hydroxyapatite coatings on Ti–6Al–4V biomedical alloy. J. Polym. Environ. 31, 4112–4126 (2023).

Ulas, B., Çetin, T., Kaya, Ş, Akinay, Y. & Kivrak, H. Novel Ti3C2X2 MXene supported BaMnO3 nanoparticles as hydrazine electrooxidation catalysts. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 58, 726–736 (2024).

Karataş, Y., Çetin, T., Akinay, Y. & Gülcan, M. Synthesis and characterization of Pd doped MXene for hydrogen production from the hydrolysis of methylamine borane: Effect of cryogenic treatment. J. Energy Inst. 109, 1–9 (2023).

Divakaran, N. et al. Novel unsaturated polyester nanocomposites via hybrid 3D POSS-modified graphene oxide reinforcement: Electro-technical application perspective. Nanomaterials 10, 1–19 (2020).

Akbari, A. et al. Cube-octameric silsesquioxane (POSS)-capped magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for the efficient removal of methylene blue. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 13, 563–573 (2019).

Fang, H., Zhang, L., Chen, A. & Wu, F. Improvement of mechanical property for PLA/TPU blend by adding PLA-TPU copolymers prepared via in situ ring-opening polymerization. Polymers (Basel) 14, 1530 (2022).

Prem Kumar, B. et al. POSS-based luminescent hybrid material for enhanced photo-emitting properties. J. Mater. Sci. 48, 7533–7539 (2013).

Zhai, W., Cao, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, M. & Wang, Z. MoO3–x QDs/MXene (Ti3C2Tx) self-assembled heterostructure for multifunctional application with antistatic, smoke suppression, and antibacterial on polyester fabric. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 2597–2609 (2022).

Li, X. et al. The effect of thermal treatment on the decomposition of phthalonitrile polymer and phthalonitrile-polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) copolymer. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 156, 279–291 (2018).

Topuz, M., Akinay, Y., Karatas, E. & Cetin, T. Ti3C2Tx MXene-functionalized hydroxyapatite/halloysite nanotube filled poly-(lactic acid) coatings on magnesium: In vitro and antibacterial applications. J. Magnes. Alloys https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jma.2024.09.017 (2024).

Zeybek, Y. M. & Kaynak, C. Behaviour of PLA/POSS nanocomposites: Effects of filler content, functional group and copolymer compatibilization. Polym. Polym. Compos. 29, S485–S500 (2021).

Barkoula, N. M., Alcock, B., Cabrera, N. O. & Peijs, T. Flame-retardancy properties of intumescent ammonium poly(phosphate) and mineral filler magnesium hydroxide in combination with graphene. Polym. Polym. Compos. 16, 101–113 (2008).

Cesarz-Andraczke, K. et al. Influence of casein on the degradation process of polylactide-casein coatings for resorbable alloys. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–14 (2024).

Falak, S., Shin, B. K. & Huh, D. S. Antibacterial activity of polyaniline coated in the patterned film depending on the surface morphology and acidic dopant. Nanomaterials 12, 1–18 (2022).

He, Q., Hu, H., Han, J. & Zhao, Z. Double transition-metal TiVCTX MXene with dual-functional antibacterial capability. Mater. Lett. 308, 131100 (2022).

Han, J. et al. Click-chemistry approach toward antibacterial and degradable hybrid hydrogels based on octa-betaine ester polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane. Biomacromolecules 21, 3512–3522 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Large-scale production of MXenes as nanoknives for antibacterial application. Nanoscale Adv. 5, 6572–6581 (2023).

Ulas, B., Cetin, T., Topuz, M. & Akinay, Y. Ti2NTx MXene materials derived from Ti2AlN MAX phases: Their characterization and electrocatalytic activity toward hydrazine electrooxidation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 82, 892–900 (2024).

Topuz, M. Hydroxyapatite – Al2O3 reinforced poly– (lactic acid) hybrid coatings on magnesium: Characterization, mechanical and in-vitro bioactivity properties. Surfaces and Interfaces 37, 102724 (2023).

Topuz, M., Dikici, B., Kasapoglu, A. E., Zhao, X. & Niinomi, M. Systematic characterization and enhanced corrosion resistance of novel β -type Ti-30Zr-5Mo biomedical alloys with halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) and zirconia (ZrO2)-reinforced polylactic acid (PLA) matrix coatings. Mater. Today Commun. 40, 110110 (2024).

Gorgisen, G. & Yaren, Z. Insulin receptor substrate 1 overexpression promotes survival of glioblastoma cells through AKT1 activation. Folia Neuropathol. 58, 38–44 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Van YYU University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit. Project Number: FCD-2023-10594. The authors would like to thank the Van Yuzuncu Yil University Science Application and Research Center and its staffs for their support in material characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuksel AKINAY: Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Erkan KARATAS: Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Damla RUZGAR: Formal Analysis, Ali AKBARI: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Dilges BASKIN: Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Tayfun CETIN: Formal Analysis, Hilal Celik KAZICI: Formal Analysis, Mehmet TOPUZ: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akinay, Y., Karatas, E., Ruzgar, D. et al. Cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane modified Ti3C2Tx MXene films. Sci Rep 15, 8463 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92498-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92498-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Electrospun poly(acrylonitrile)/lithium perchlorate-grafted MXene composite nanofibrous membrane as polymer electrolyte for energy storage applications

Journal of Materials Science (2025)

-

Review: recent developments in 2D MXene-filled bioinspired composites for biomedical applications

Journal of Materials Science (2025)