Abstract

This study aimed to analyze S100A9 and CCL5 levels in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and evaluate their predictive value as blood-based indicators for NPC diagnosis. Serum S100A9 and CCL5 levels were measured in 123 patients newly diagnosed with NPC and 107 patients without NPC. Additionally, 38 patients (19 with NPC and 19 without) were recruited from Xiangya Hospital as an external validation cohort. Logistic regression was used to identify risk factors for NPC. Variable selection was conducted using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression. NPC prediction models were developed using four machine-learning algorithms, and their performance was evaluated with ROC curves. Calibration curves, decision curve analysis (DCA), and Shapley additive explanation plots were employed for further evaluation and interpretation. Serum S100A9 and CCL5 levels were significantly elevated in patients with NPC compared with patients without NPC. Multivariate logistic regression identified S100A9, CCL5, TP, and ALB as independent predictors of NPC. ROC analysis demonstrated that S100A9 had superior diagnostic performance compared to CCL5 and other blood indicators, effectively differentiating NPC from non-NPC cases. A machine-learning-based logistic regression model incorporating S100A9, CCL5, ALB, GLB, and PLR demonstrated a reliable diagnostic value for NPC, achieving an Area under the curve (AUC) of 0.877 in the training cohort. The calibration curve showed excellent agreement between predicted and actual probabilities; in contrast, the DCA curve highlighted strong clinical utility. The model also performed well in the external validation cohort, with an AUC of 0.817. Serum levels of S100A9, CCL5, and other indicators such as GLB, ALB, and PLR have diagnostic values for NPC. The logistic regression model based on these biomarkers demonstrated robust predictive performance and clinical utility for NPC diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant tumor originating in the epithelial cells of the nasopharynx with a high incidence in southern China and Southeast Asia. Global cancer statistics estimated 120,416 incidences and 73,476 deaths from NPC worldwide in 20221. Asia accounted for 83.3% of global NPC incidence (100,298 cases) and 83.6% of deaths (61,442 cases)2. China had the highest incidence rate of 51,010 cases with an age-standardized incidence rate of 2.4 cases per 100,000 people2. Early diagnosis of NPC remains challenging due to its deep anatomical location and the lack of overt clinical symptoms in its early stages. Consequently, most patients with NPC are diagnosed at an advanced stage, which increases the risk of cervical lymph node and/or distant metastasis and negatively affects prognosis3. This highlights the urgent need to identify novel biomarkers for the early detection of NPC. Despite recent advances in NPC diagnostics, nasopharyngeal endoscopy combined with histopathological examination remains the gold standard. However, the compliance rate for this procedure is low due to its invasiveness and high costs. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a significant etiological factor for NPC, and various EBV-related tests, including those for EBV DNA and antibodies, have been developed. Nevertheless, their sensitivity and specificity are insufficient to meet clinical needs4,5. As a result, there is a critical demand for a noninvasive, high-precision method for NPC diagnosis.

S100A9 is a member of the S100 family of calcium-binding proteins and is closely associated with tumorigenesis and progression. It binds Ca2+ and Zn2+ ions with high selectivity and affinity, exhibiting extracellular and intracellular regulatory activities. S100A9 is involved in processes such as cell migration, arachidonic acid metabolism, and bone marrow cell maturation6. Previous studies have shown that S100A9 expression is upregulated in various primary and invasive tumors7,8. Li et al.9 utilized laser capture microdissection to isolate stromal cells from NPC and normal nasopharyngeal epithelial tissues, followed by two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry, to demonstrate elevated S100A9 protein levels in NPC stromal cells. However, its expression in the serum of patients with NPC has rarely been reported.

CCL5, a member of the C-C motif chemokine family, binds with high affinity to its receptor CCR5. It is generally recognized that CCL5 attracts T cells and monocytes. CCL5 plays a dual role in cancer: on one hand, it accelerates tumor progression and metastasis10,11; conversely, it enhances anti-tumor immunity by recruiting anti-tumor T cells and dendritic cells to the tumor microenvironment12,13. Overexpression of CCL5 has been observed in several cancers, including breast cancer14,15, esophageal cancer16, gastric cancer17, colorectal carcinoma18,19, prostate cancer20, pancreatic cancer21, and acute lymphocytic leukemia22. However, its role in NPC has not been elucidated.

In this study, we investigated the expression levels of S100A9, CCL5, routine blood indices, and common biochemical indices in the serum of patients with NPC compared with non-NPC controls, including patients with benign nasopharyngeal lesions and healthy individuals. Additionally, we successfully developed models to evaluate the diagnostic and predictive utility of these blood biomarkers for NPC.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

This cross-sectional study recruited 123 patients with NPC and 107 non-NPC controls (34 patients with benign nasopharyngeal conditions such as nasal polyps or rhinitis and 73 healthy subjects) from Xiangya Hospital of Central South University between January 2024 and May 2024. The inclusion criteria were: (a) diagnosis of NPC confirmed by histopathology and (b) availability of complete clinicopathological and baseline data. The exclusion criteria were (a) pregnancy, (b) the presence of other malignancies or prior antitumor treatment, (c) hemolyzed samples, and (d) incomplete patient information. The patient selection process is illustrated in the flowchart in Fig. 1.

Demographic and clinicopathological data, including sex, age, and cancer stage, were collected. Laboratory examinations included routine blood tests and biomedical analyses. All laboratory data were obtained before initiating treatment. All participants provided informed consent, and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

An external validation cohort was also recruited, comprising 19 patients with an initial diagnosis of NPC and 19 non-NPC controls (four with benign nasopharyngeal conditions and 15 healthy individuals) who visited Xiangya Hospital between June and July 2024.

Blood routine examination

Venous blood (3–5 ml) was collected in a K2EDTA anticoagulant tube in the morning, and routine blood examinations were performed using the Beckman Coulter DxH 800 blood cell analyzer. The following counts were measured: WBC, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, and platelet (PLT). The inflammatory markers were calculated as follows: the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), which is the ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes; the lymphocyte-monocyte ratio (LMR), which is the ratio of lymphocytes to monocytes; and the PLR (platelet-lymphocyte ratio), which is the ratio of platelets to lymphocytes.

Biomedical test

Venous blood (3–5 ml) was collected in a tube containing separation gel after 10 h of fasting, and the blood was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Biomedical tests were performed using the Beckman AU5800 automatic biochemical analyzer. The following levels were measured: total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), globulin (GLB), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), total bile acid (TBA), alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, triglyceride, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC).

Measurement of S100A9 and CCL5

All serum samples were quickly frozen after centrifugation and stored at − 80 °C until testing. The samples were thawed only once to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Serum levels of S100A9 and CCL5 were measured using ELISA kits (Beyotime, Nanjing, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 27.0; SPSS Inc., IL, USA). Data normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation; in contrast, nonnormally distributed data are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges. Group comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was employed to identify risk factors of NPC. Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine independent risk factors for NPC. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to assess the diagnostic value of blood indicators for NPC. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

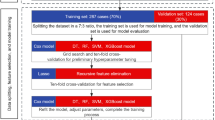

Predictive model construction using machine learning

Feature selection and predictive model construction were performed using Deepwise and the Beckman Coulter DxAI platform v2.0 (https://www.xsmartanalysis.com/). LASSO regression was applied to determine the importance of the influencing factors. Following feature selection, predictive models were developed using four machine-learning algorithms: logistic regression, XGBoost classifier, LightGBM classifier, and random forest classifier. Five-fold cross-validation was used to evaluate the performance of these algorithms. In this method, the dataset was randomly divided into five subsets: four subsets served as the training set for model construction; in contrast, the remaining subset was used as the internal validation set. This process was repeated five times to ensure a robust evaluation of the model performance.

The optimal predictive model was selected based on its performance in the internal validation set. In the training and validation sets, ROC curves and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) were used to assess the model’s performance. Calibration was further evaluated graphically using calibration plots. Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) was employed to evaluate the clinical utility of the model; in contrast, Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) plots were used to illustrate feature rankings. All P values were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparisons of clinical characteristics of participants

A total of 230 participants were enrolled in the study, comprising 123 individuals with NPC and 107 non-NPC participants (34 with benign nasopharyngeal diseases such as nasal polyps or rhinitis and 73 healthy subjects). The clinical characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age or sex between the two groups (P > 0.050). Among the 123 patients with NPC, 83 (67.5%) were male, and 40 (32.5%) were female, compared with 70 males (65.4%) and 37 females (34.6%) in the non-NPC group. The mean age of the NPC group was 52.26 ± 10.80 years, compared to 49.50 ± 12.11 years in the non-NPC group. The distribution of NPC stages was as follows: 53 patients (12.2%) in stages I + II, 45 patients (36.6%) in stage III, and 64 patients (51.2%) in stage IV.

The NPC group showed significantly higher levels of S100A9, CCL5, TP, GLB, LDLC, neutrophil, PLT, NLR, and PLR compared to the non-NPC group (P < 0.05). Conversely, levels of ALB, TBIL, DBIL, TBA, lymphocytes, and LMR were significantly lower in the NPC group (P < 0.05) compared to controls.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with different stages of NPC

As shown in Table 2, the majority of patients with NPC (87.8%) were diagnosed with advanced stage III/IV disease. Notably, levels of S100A9, ALB, GLB, WBC, neutrophil, and NLR varied significantly among different NPC stages (P < 0.05). The levels of S100A9, GLB, WBC, neutrophils, and NLR were significantly higher in patients with more advanced stages than in those with earlier stages; in contrast, ALB levels were significantly lower in patients with advanced stages than in those with earlier stages.

Prediction factors for NPC analyzed by logistic regression

In this study, univariate logistic regression was used to analyze 24 potential risk factors to determine their association with the occurrence of NPC (Table 3). Eleven predictive factors were identified as being significantly associated with the incidence of NPC: S100A9, CCL5, TP, ALB, GLB, DBIL, LDLC, neutrophils, PLT, NLR, and PLR. Subsequently, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed on these 11 factors, revealing that S100A9, CCL5, TP, and ALB (P < 0.05) were independent predictive factors for the incidence of NPC (Table 3).

LASSO regression for prediction factors

This study collected 24 features of patients newly diagnosed with NPC. After excluding irrelevant and redundant features, 15 features (S100A9, CCL5, TP, ALB, GLB, TBIL, DBIL, TBA, LDLC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, PLT, PLR, NLR, and LMP) were retained for LASSO regression analysis. LASSO regression was then applied to identify factors associated with NPC. The results indicated that S100A9, CCL5, ALB, GLB, TBA, LDLC, NLR, and PLR were the most relevant factors linked to NPC (Fig. 2).

Predictor selection using LASSO regression analysis. (A) Bias selection of the tuning parameter (λ) in LASSO regression based on the minimum standard (left dashed line) and 1-SE standard (right dashed line). (B) Tenfold cross-validation for tuning parameter selection in LASSO regression, with a joint plot based on log-likelihood. The 1-SE standard (right dashed line) was used to select predictive factors for this study. SE: standard error.

Diagnostic value of S100A9, CCL5, and other blood biomarker for NPC

The diagnostic values of S100A9, CCL5, and other blood markers for NPC were assessed using univariate ROC analysis. The results showed that S100A9 had the highest diagnostic efficacy, with an AUC value of 0.803 (Fig. 3A; Table 4). Based on the ROC curve coordinates, the cutoff value for S100A9 concentration was determined to be 40.396 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 77.2% and specificity of 73.8%. Other biomarkers, including GLB (AUC = 0.789), NLR (AUC = 0.754), PLR (AUC = 0.750), and CCL5 (AUC = 0.731) also showed good diagnostic performance. In contrast, TBA (AUC = 0.606), ALB (AUC = 0.597), and LDLC (AUC = 0.594) demonstrated poor diagnostic efficacy.

Comparison of machine learning algorithms and identification of the optimal predictive model

To improve the diagnostic value of serum S100A9 levels in distinguishing between patients with NPC and non-NPC, machine learning models were constructed that combined S100A9 levels with other variables to evaluate their predictive reliability. Four machine learning algorithms were utilized: logistic regression, XGBoost, LightGBM, and random forest classifiers. The optimal predictive model was identified based on its performance in the internal validation set. In the validation cohort, all four models achieved an AUC exceeding 0.85. The logistic regression model exhibited the best performance, with an AUC of 0.868; in contrast, the AUC of XGBoost, Random Forest, and LightGBM were 0.860, 0.856, and 0.854, respectively (Fig. 3B; Table 5).

The Logistic Regression model demonstrated the highest predictive performance among the tested algorithms. Using feature ranking within the logistic regression model, the top five features—GLB, ALB, CCL5, S100A9, and PLR—were selected for final model construction. As shown in Table 6; Fig. 4, the model exhibited strong discriminatory ability in distinguishing NPC from non-NPC. In the training and validation cohorts, the AUC of the model exceeded 80% (Fig. 4A and B). Additionally, the calibration curve revealed a strong correlation between the predicted and actual outcomes, indicating excellent calibration. The DCA curves (Fig. 4C and D) further demonstrated that the model provided substantial clinical benefit.

As illustrated in Fig. 5A and B, the SHAP algorithm was used to interpret feature importance in the logistic regression model. GLB, PLR, CCL5, ALB, and S100A9 were identified as the most influential features for predicting NPC outcomes. A larger mean absolute Shapley value indicated a greater impact on the model’s predictions.

SHAP-based interpretation of the logistic regression model. (A) SHAP values illustrate the influence of each feature on the outcome. Each point represents one sample. Higher feature values are shown in red; in contrast, lower feature values are shown in blue. (B) Ranking of feature importance based on SHAP analysis. (C) SHAP force plot for patients with NPC, visualizing the contribution of individual features to predictions.

Figure 5C provides individual force plots for NPC and non-NPC predictions. For patients with NPC, the probability prediction value was 0.84. Positive contribution features, shown in red, pushed the prediction score higher; in contrast, negative contribution features, shown in blue, reduced the score. The length of each arrow represents the magnitude of a feature’s impact on the prediction, with longer arrows indicating greater influence.

A web-based tool was developed using the Deepwise and Beckman Coulter DxAI platform v2.0. This tool allows users to input parameter values to predict the risk of NPC. Patients are categorized as NPC and non-NPC based on calculated probabilities. http://www.xsmartanalysis.com/model/list/predict/model/html?mid=19297&symbol=6anUc17318ru57DY5035.

External validation of the logistic regression model

An external validation cohort comprising 38 patients (19 with an initial diagnosis of NPC and 19 without NPC) was recruited from Xiangya Hospital between June and July 2024. As shown in Fig. 6, the AUC of the model for the external validation cohort was 0.817, confirming its predictive reliability.

Discussion

The use of readily available blood tests to screen high-risk individuals offers a potential alternative to relatively hard-to-obtain or expensive imaging modalities and invasive nasopharyngeal endoscopy. After evaluating clinical symptoms, if a patient exhibits signs suggestive of NPC, clinicians can further use predictive models based on blood markers to assess disease risk to guide the next steps. This approach has the potential to reduce unnecessary patient expenditure on invasive tests. In this study, S100A9, CCL5, and other common hematological markers were combined to evaluate their predictive accuracy for NPC. Furthermore, LASSO regression was employed to reduce dimensionality and avoid model overfitting, making it a widely used technique for variable selection and prediction model optimization23.

Our findings revealed that serum levels of S100A9 and CCL5 were significantly elevated in patients with NPC. The elevated serum S100A9 levels were consistent with previous findings9, indicating high expression of S100A9 in NPC tissues. In this study, S100A9 demonstrated the best diagnostic efficacy for NPC, with an AUC of 0.803, sensitivity of 77.2%, and specificity of 73.8%. Additionally, S100A9 levels were significantly higher in patients with advanced-stage disease than in those with early-stage disease. S100A9 is a potent proinflammatory mediator involved in acute and chronic inflammation and plays a pivotal role in inflammation-associated cancers7. Elevated S100A9 levels have been reported in various cancers24,25. As an inflammatory factor, S100A9 has strong chemotactic effects on leukocyte aggregation, adhesion, and migration, amplifying local proinflammatory microenvironments26. Studies27,28 have shown that S100A9 promotes tumor growth and progression by binding to cell surface receptors, increasing NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activity, and modulating inflammatory and immune responses. It activates cytokines such as TNFα, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β through the NF-κB pathway29 and creates a feedback loop by stimulating the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines30. Guo et al.31 demonstrated that the PI3K/Akt pathway is crucial for NPC progression, and a recent study32 suggested that S100A9 may influence NPC proliferation via this pathway.

CCL5, a member of the CC chemokine subfamily, binds to CCR1, CCR3, CCR4, and CCR5, with the highest affinity for CCR533. Recent research has explored the role of the CCL5/CCR5 axis in various cancers, including gastric, pancreatic, breast, and head and neck cancers33. CCL5/CCR5 activates pathways such as PI3K/AKT, NF-κB, and ERK/MEK, driving abnormal tumor cell proliferation. Additionally, these pathways regulate MMP and inflammatory factors, facilitating tumor metastasis and invasion34.

Among blood abnormalities observed in patients with NPC, increased levels of TP, GLB, LDLC, neutrophils, PLT, NLR, and PLR were notable. Conversely, ALB, TBIL, DBIL, TBA, lymphocytes, and LMP levels were significantly lower compared to controls (P < 0.05). Chronic inflammation is closely linked to cancer development. Peripheral blood markers such as neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, and platelet counts, as well as derived indices like NLR and PLR, are cost-effective and noninvasive inflammatory markers widely used in cancer research. Elevated serum GLB levels, induced by proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα, reflect systemic inflammation35. Previous studies36,37 have linked high GLB levels not only to inflammatory responses but also to tumor initiation, recurrence, and outcomes. ALB, indicative of nutritional status, has been associated with tumor progression and malignancy38.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses identified S100A9, CCL5, TP, and ALB as independent factors influencing NPC risk.

These markers, along with GLB and PLR, were used to develop a predictive logistic regression model, which demonstrated strong performance and clinical applicability. The model exhibited excellent discrimination (AUC = 0.877) and calibration in the internal validation cohort, with similar results (AUC = 0.817) in the external validation cohorts. These findings align with prior studies, such as that conducted by Wu et al.39, however, our study uniquely incorporated routine blood parameters.

Clinically, we developed a predictive model for NPC using S100A9, CCL5, ALB, GLB, and PLR levels. This model may enhance early diagnosis of NPC and provides a foundation for future research. However, this study has some limitations. First, this study was conducted in a single center, with both the training cohort and the external validation cohort being data sources from the same hospital, and thus may have suffered from selection bias. Second, the study lacked prospective data, had a small external validation sample size. While using the existing methodology, we also used 10-fold cross-validation and Bootstrap simulation to similarly validate the reliable diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of the predictive model40,41 (As shown in Supplementary material). Nevertheless, a larger, well-powered study might be necessary to validate the findings. Future studies will be aim to increase the sample size and conduct multicenter studies in collaboration with multiple hospitals for larger and more diverse patient populations. Third, our analysis of blood markers such as S100A9 and CCL5 was limited to expression levels; further investigations are needed to identify the signaling pathways influenced by these molecules and to elucidate their roles in NPC pathogenesis and progression. In the future, we will thoroughly explore whether treatment or coexisting health issues affect levels of S100A9, CCL5, or the other biomarkers, and take a closer look at potential confounding factors.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrated that serum levels of S100A9, CCL5, and other blood indicators, including GLB, ALB, and PLR, hold diagnostic value for NPC. The logistic regression model based on these biomarkers showed strong predictive performance and clinical utility. However, large clinical trials are needed to confirm these results.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

12 June 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Lu Long and Ya Tao were omitted as equally contributing authors.

Abbreviations

- ALB:

-

Albumin

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- AUC:

-

Area under the ROC curve

- CCL5:

-

C–C motif chemokine ligand 5

- DBIL:

-

Direct bilirubin

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- EBV:

-

Epstein-barr virus

- GLB:

-

Globulin

- HDLC:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- LDLC:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LMR:

-

Lymphocyte-monocyte ratio

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio

- NPC:

-

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- PLR:

-

Platelet-lymphocyte ratio

- PLT:

-

Platelet

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- S100A9:

-

S100 calcium binding protein A9

- SHAP:

-

Shapley additive explanations

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Su, Z. Y., Siak, P. Y., Lwin, Y. Y. & Cheah, S. C. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: current insights and future outlook. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 43, 919–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-024-10176-9 (2024).

Lu, T. et al. Circulating Epstein-Barr virus MicroRNAs BART7-3p and BART13-3p as novel biomarkers in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 111, 1711–1723. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.14381 (2020).

Tan, R. et al. Clinical utility of Epstein-Barr virus DNA and other liquid biopsy markers in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Commun. (London England). 40, 564–585. https://doi.org/10.1002/cac2.12100 (2020).

AbuSalah, M. A. H. et al. Recent advances in diagnostic approaches for Epstein-Barr virus. Pathogens 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9030226 (2020).

Heizmann, C. W., Ackermann, G. E. & Galichet, A. Pathologies involving the S100 proteins and RAGE. Subcell. Biochem. 45, 93–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6191-2_5 (2007).

Gebhardt, C., Nemeth, J., Angel, P. & Hess, J. S100A8 and S100A9 in inflammation and cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 1622–1631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.017 (2006).

Chen, Y., Ouyang, Y., Li, Z., Wang, X. & Ma, J. S100A8 and S100A9 in Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 1878, 188891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2023.188891 (2023).

Li, M. X. et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of differential proteins in the stroma of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and normal nasopharyngeal epithelial tissue. J. Cell. Biochem. 106, 570–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.22028 (2009).

Kato, T. et al. CCR1/CCL5 interaction promotes invasion of taxane-resistant PC3 prostate cancer cells by increasing secretion of MMPs 2/9 and by activating ERK and Rac signaling. Cytokine 64, 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2013.06.313 (2013).

Karnoub, A. E. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature 449, 557–563. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06188 (2007).

Bottcher, J. P. et al. NK Cells Stimulate Recruitment of cDC1 into the Tumor Microenvironment Promoting Cancer Immune Control. Cell 172, 1022–1037 e1014, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.004

Huffman, A. P., Lin, J. H., Kim, S. I., Byrne, K. T. & Vonderheide, R. H. CCL5 mediates CD40-driven CD4 + T cell tumor infiltration and immunity. JCI Insight. 5 https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.137263 (2020).

Velasco-Velazquez, M. et al. CCR5 antagonist blocks metastasis of basal breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 72, 3839–3850. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3917 (2012).

Jiao, X. et al. CCR5 governs DNA damage repair and breast Cancer stem cell expansion. Cancer Res. 78, 1657–1671. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0915 (2018).

Wu, Y. C. et al. Autocrine CCL5 promotes tumor progression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in vitro. Cytokine 110, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2018.04.027 (2018).

Aldinucci, D. & Casagrande, N. Inhibition of the CCL5/CCR5 Axis against the progression of gastric Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19051477 (2018).

Halama, N. et al. Tumoral immune cell exploitation in colorectal cancer metastases can be targeted effectively by Anti-CCR5 therapy in cancer patients. Cancer Cell. 29, 587–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.005 (2016).

Pervaiz, A., Ansari, S., Berger, M. R. & Adwan, H. CCR5 blockage by Maraviroc induces cytotoxic and apoptotic effects in colorectal cancer cells. Med. Oncol. 32, 158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-015-0607-x (2015).

Vaday, G. G., Peehl, D. M., Kadam, P. A. & Lawrence, D. M. Expression of CCL5 (RANTES) and CCR5 in prostate cancer. Prostate 66, 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.20306 (2006).

Singh, S. K. et al. CCR5/CCL5 axis interaction promotes migratory and invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 8, 1323. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19643-0 (2018).

Zi, J. et al. Treatment with the C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5)-inhibitor Maraviroc suppresses growth and induces apoptosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Am. J. cancer Res. 7, 869–880 (2017).

Pajouheshnia, R., Pestman, W. R., Teerenstra, S. & Groenwold, R. H. A computational approach to compare regression modelling strategies in prediction research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 16, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0209-0 (2016).

Zhou, M. et al. The significance of serum S100A9 and TNC levels as biomarkers in colorectal Cancer. J. Cancer. 10, 5315–5323. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.31267 (2019).

Moravkova, P., Kohoutova, D., Vavrova, J., Bures, J. & Serum S100A6, S100A8, S100A9 and S100A11 proteins in colorectal neoplasia: results of a single centre prospective study. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 80, 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365513.2019.1704050 (2020).

Kwon, C. H., Moon, H. J., Park, H. J., Choi, J. H. & Park, D. Y. S100A8 and S100A9 promotes invasion and migration through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent NF-kappaB activation in gastric cancer cells. Mol. Cells. 35, 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10059-013-2269-x (2013).

Nishikawa, Y. et al. Calprotectin induces IL-6 and MCP-1 production via Toll-Like receptor 4 signaling in human gingival fibroblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 232, 1862–1871. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25724 (2017).

Leclerc, E., Fritz, G., Weibel, M., Heizmann, C. W. & Galichet, A. S100B and S100A6 differentially modulate cell survival by interacting with distinct RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end products) Immunoglobulin domains. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31317–31331. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M703951200 (2007).

Simard, J. C. et al. S100A8 and S100A9 induce cytokine expression and regulate the NLRP3 inflammasome via ROS-dependent activation of NF-kappaB(1). PLoS One. 8, e72138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072138 (2013).

Boyd, J. H., Kan, B., Roberts, H., Wang, Y. & Walley, K. R. S100A8 and S100A9 mediate endotoxin-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction via the receptor for advanced glycation end products. Circ. Res. 102, 1239–1246. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167544 (2008).

Guo, Q. et al. Genetic variations in the PI3K-PTEN-AKT-mTOR pathway are associated with distant metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Sci. Rep. 6, 37576. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37576 (2016).

Wen, L. et al. Influences of S100A8 and S100A9 on Proliferation of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells through PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Biomed Res Int 9917365, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9917365 (2021).

Aldinucci, D., Borghese, C. & Casagrande, N. The CCL5/CCR5 Axis in Cancer progression. Cancers (Basel). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071765 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Endothelial cells enhance prostate cancer metastasis via IL-6–>androgen receptor–>TGF-beta–>MMP-9 signals. Mol. Cancer Ther. 12, 1026–1037. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0895 (2013).

Du, X. J. et al. The pretreatment albumin to Globulin ratio has predictive value for long-term mortality in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One. 9, e94473. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094473 (2014).

Alacacioglu, A., Tarhan, O., Alacacioglu, I., Dirican, A. & Yilmaz, U. Depression and anxiety in cancer patients and their relatives. J. BUON. 18, 767–774 (2013).

Qu, X. et al. High percentage of alpha1-globulin in serum protein is associated with unfavorable prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Med. Oncol. 31, 238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0238-7 (2014).

Weimann, A. et al. ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin. Nutr. 40, 4745–4761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2021.03.031 (2021).

Wu, J., Luo, H., Wang, K. & Yi, B. Development and validation of a novel diagnostic nomogram model using serum oxidative stress markers and AURKA for prediction of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 15, 1053–1062. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S402572 (2023).

Huang, A. A. & Huang, S. Y. Use of machine learning to identify risk factors for coronary artery disease. PLoS One. 18, e0284103. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0284103 (2023).

Huang, A. A. & Huang, S. Y. Increasing transparency in machine learning through bootstrap simulation and shapely additive explanations. PLoS One. 18, e0281922. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281922 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of the participants and contributors. We thank Mr. Xinrui Liang, Mr. Yuming Cheng and Ms. Xialin Wang from Beckman Coulter Commercial Enterprise Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for their technical support in building the prediction model.

Funding

The study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (No. 2023JJ40971, No. 2023JJ30965).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL designed the study, collected, analysed, and interpreted data, contributed to manuscript writing. YT designed the study, collected and analysed the data. WZY, QZH, YLL, KKH and HDL collected and analysed the data. BY amended the first draft and approved the final version. All authors read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (No. 2024101312), and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Long, L., Tao, Y., Yu, W. et al. Multiparameter diagnostic model using S100A9, CCL5 and blood biomarkers for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 7502 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92518-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92518-3