Abstract

In radiation therapy, precise dose distribution is essential for minimizing damage to normal tissues. Gafchromic EBT3 film is widely used to assure the quality of two-dimensional dosimetry but requires frequent recalibrations due to changes in sensitivity over time. This study presents a new calibration method using a Keras-based generalized additive neural network (GANN) to address film aging. EBT3 films from four lots were calibrated with a 6 MV photon beam and scanned on Epson scanners. The GANN method achieved percentage differences between calibrated and delivered doses within 5%, comparable to traditional recalibration methods, with an overall uncertainty of approximately 2%. It demonstrated improved stability and accuracy, significantly reducing the need for frequent recalibrations and providing a robust solution for long-term film dosimetry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To improve survival and reduce toxicity to normal tissues, dose-painting strategies and inverse treatment plans are frequently used in radiation therapy. In these methods, both spatial and dosimetric accuracy, particularly with steep dose gradients, must be verified using two-dimensional dosimetry tools1,2. Gafchromic EBT film is an economical and widely used tool for quality assurance, which offers high spatial resolution, self-development, extensive dynamic dose range, dose-rate independence, and relative energy independence in the MV range; however, it displays increased sensitivity at kV energies3.

Ashland® recommends the EBT3 film model for verifying all beam-modulated techniques4. It has minimal side effects5, is less sensitive to the visible spectrum, because of its yellow marker dye6,7,8,9,10,11,12, enables repeated scans13,14, and avoids the formation of Newton’s rings due to its matte polyester substrate15,16,17,18. Its near water-equivalent properties, with an atomic number of approximately 7.3, further enhance its suitability for patient dosimetry14,19,20,21.

Over time, however, film sensitivity gradually changes when left unused, a phenomenon known as the ‘film aging effect’21,22,23,24,25,26. Film aging can be mitigated by subtracting the background using the net optical density when calibrated with conventional methods21. This approach requires periodic recalibration21,24,26, which is burdensome, costly, and time-consuming.

Film can generally be calibrated by extracting net optical density27, pixel value14, and inverse transmittance28 using appropriate equations. Recently, Zhuang et al. calibrated different EBT3 lots with optical density inputs using the PyTorch artificial neural network platform29, achieving a mean square error (MSE) of 18 cGy with 400 training inputs from six films. To calibrate EBT3 film, a hierarchical neural network (HNN) was developed using the Keras functional application program interface20. This HNN, consisting of artificial neural network (ANN) subnets that handle specific input aspects, was previously applied to survival analysis30 and is now utilized to address film aging effects and intra-lot variation. However, the HNN method might be unstable and may not perform reliably for other film lots.

Instead of general recalibrations, the adaptive method calculates film dose using all fitting parameters from the initial calibration, adjusting only the constant parameter with a newly measured background optical density. Although this approach has demonstrated reliable accuracy21, it relies on an empirical constant with high uncertainty, where even a small change can introduce significant errors21. To overcome these limitations, we developed a new approach using a GANN in Keras.

Materials and methods

Phantom setup and film positioning

First, 8″ × 10″ EBT3 films from four different lots (Lot C #03211802, Lot G #12131902, Lot H #01202003, and Lot I #03022001) were calibrated separately over several months using a 6 MV photon beam from an Elekta Synergy accelerator. A custom-made acrylic frame measuring 46 × 32 × 0.2 cm3 was constructed with a centered 8″ × 10″ rectangular opening to ensure consistent film placement on the scan bed. This transparent frame fits securely on the scan bed in portrait orientation. The films were scanned using an Epson 10000XL scanner and an Epson 12000XL scanner in a fixed portrait orientation, both before and after irradiation, to produce 127 dpi TIFF images. The film’s longitudinal midline divides it into two equal parts positioned near the scan bed’s midline and parallel to the scan direction; therefore, no correction for scanner non-uniformities is required when extracting pixel values27,31,32.

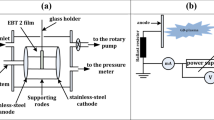

This study used a modified percentage-depth-dose (PDD) calibration method14,21,27,28,32,33,34,35. After the output calibration, the chamber was removed21, and a calibration phantom made of six 5 × 30 × 30 cm3 PTW RW3 polystyrene blocks with a sandwiched film was immediately placed on the couch. An additional 10 × 30 × 30 cm3 block was positioned beneath the calibration phantom to provide adequate backscatter (Fig. 1a). The longitudinal midline of the sandwiched film aligns with the central beam, and the upper edge of the film is aligned with the gantry’s rotational axis (Fig. 1b). The field size was set to 20 × 20 cm2, and the source-to-surface distance was 100 cm.

Irradiation and dose calibration

Before each calibration, the accelerator output was calibrated according to AAPM TG reports36,37,38,39. Using the PDD method, two different monitor units were assigned to two separate films. After 24 h, each film was re-scanned and analyzed using MATLAB software. The absorbed dose range along the midline is 40 to 100 cGy for one film and 100 to 300 cGy for the other, calculated using a verified PDD table with scaling factor correction14 and the preceding output calibration.

The adaptive method

A modified three-channel (MTC) technique28 was initially used to calibrate the film. Ignoring lateral effects, the dose-dependent optical density (OD) of the red channel along the midline, ODR, was fitted to the delivered dose Dd, including the mean background ODR at zero cGy, using a power function40,41.

where FD is the fitted dose for ODR; A, B, C, and D are fitting parameters. The fitting process was repeated twice, with constraints applied only to C. To reduce uncertainty, C was initially restricted to a range between 2.8 and 3.2, then set to the nearest tenth based on the result of the first fit42.

For the nth film calibration using a specified lot box, the dose-dependent OD for the red channel for the nth calibration, ODRn, was fitted to the delivered dose using Eq. (2):

where FDn is the fitted dose for ODRn; An, Bn, Cn, and Dn are fitting parameters for the nth calibration. The fitting process included the dataset for 0 cGy and ODRn_bg, the average value of ODRn for the nth background image. After the initial calibration, re-exposure of the film was unnecessary for subsequent calibrations; only a background image was needed when using the adaptive method21. Thus, Eq. (2) can be rewritten as:

where DFn is the film dose for the nth calibration; A1, B1, and C1 are fitting parameters for the 1st calibration. Δn is the adaptive parameter for the nth calibration, and Δ1 = D1.

For the first calibration, there exists a dose-dependent OD for the red channel, ODR1_Fbg, that makes FD1 zero (Eq. 2). Accordingly,

ODR1_Fbg is solved using ‘fzero’, the root of a nonlinear function in MATLAB software. Let ε be the difference between ODR1_Fbg and ODR1_bg, so that \({\text{OD}}_{{{\text{R}}1\_{\text{Fbg}}}} = {\text{OD}}_{{{\text{R}}1\_{\text{bg}}}} + {\upvarepsilon }\).

For the nth calibration, there is an ODRn_Fbg that results in a zero dose to the film. Therefore,

\({\text{OD}}_{{{\text{Rn}}\_{\text{Fbg}}}} {\text{ can be written as OD}}_{{{\text{Rn}}\_{\text{bg}}}} + {\upvarepsilon }\)21, where ODRn_bg is the mean background OD for the nth calibration. The adaptive film dose for the nth calibration can then be written as:

Keras GANN deep learning method

A challenge with the adaptive method is “ε”, the OD difference between calculated and measured backgrounds, which serves as a bias adjustment obtained from the first and second calibration results. ε must be accurate and chosen carefully; adding even 0.001 would increase the average difference by 2% compared with delivered doses21. To address this issue, a new method using a Keras GANN43 was developed to enable the nth calibration to be performed robustly using only the first calibration parameters and the background OD of that film.

The exponent in Eq. (1) generally varies among films and film ages. Therefore, a variable “τ” is added to exponent C1 as a bias adjustment to improve the accuracy of the new calibration method. The OD of the irradiated film should also vary with ε. Equation (6) can then be rewritten as:

where ε and τ are functions dependent on ODRn and ODRn_bg. Thus, ε = ε(ODRn, ODRn_bg) and τ = τ (ODRn, ODRn_bg). Because ε and τ are two unknown functions, Eq. (7) satisfies the generalized additive partially linear model43,44 and can be trained using a GANN, constructed in the Keras functional application program interface.

Several GANN programs were written using Spyder software with Python 3.11, running on the TensorFlow machine learning platform. To enable the DFn approach to deliver doses, A1, B1, C1, ODR1, ODR1_bg, and the respective delivered dose Dd were essential training inputs, previously calculated in MATLAB. The ANN uses a 1–5–7–1 configuration, with one input, five neurons in the first hidden layer, seven neurons in the second hidden layer, and one output for the function ε, and a 1–6–8–1 configuration for the function τ. In this program, ‘Relu,’ ‘Selu,’ and ‘Linear’ are used as activation functions. The initial weights were set to “uniform,” and the random number generator seed was set to 321. The program structure is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Detailed structure of the deep learning GANN program. Examining Eq. 7 and the illustration, “tau” is “τ”; “epsilon” is “ε”; “OD_Rn_power” is \(({\text{OD}}_{{{\text{Rn}}}} + {\upvarepsilon })^{{({\text{C}}_{1} + \tau )}}\); “OD_Rnbg_power” is \(({\text{OD}}_{{{\text{Rn}}\_{\text{bg}}}} + {\upvarepsilon })^{{({\text{c}}_{1} + \tau )}}\); “OD_Rn_all” is \({\text{A}}_{1} \times ({\text{OD}}_{{{\text{Rn}}}} + {\upvarepsilon }) + {\text{B}}_{1} \times ({\text{OD}}_{{{\text{Rn}}}} + {\upvarepsilon })^{{({\text{C}}_{1} + {\uptau })}}\); “OD_Rn_bg_all” is \(\left[ {{\text{A}}_{1} \times ({\text{OD}}_{{{\text{Rn}}\_{\text{bg}}}} + {\upvarepsilon }} \right) + {\text{B}}_{1} \times ({\text{OD}}_{{{\text{Rn}}\_{\text{bg}}}} + {\upvarepsilon })^{{({\text{C}}_{1} + \tau )}} ]\).

The optimization algorithm ‘Adam,’ a combination of momentum and root mean square propagation, is used here in place of a classical stochastic gradient descent to update network weights more efficiently. Because the training process involves a multiple-regression problem, Adam optimizes a mean squared error (MSE) objective function, which is a suitable metric for evaluating model performance. The metric used in this GANN is the mean absolute error (MAE). The fitting process was executed over 2000 epochs with a batch size of 40. The validation split is 0.4, indicating that 40% of the training data were held back for validation. The numbers of hidden layers, neurons, and activation functions were systematically adjusted to ensure the calculated doses aligned with the delivered doses. This alignment was evaluated using MSE and MAE values and visualized by comparing the delivered doses with the calculated doses. After training, the ODRn and ODRn_bg datasets were used as input to calculate DFn and compared with the delivered doses. At a distance from the longitudinal midline of the film, the dose is calculated with lateral effect corrections, as outlined in Eqs. 10–12 of the MTC technique paper28.

Films from lots C, G, H, and I were calibrated on different dates; the second and third calibrations were conducted 100 to 430 days after the first calibration. To explore long-term calibration using general net optical density27 at approximately 250 days after the first calibration, both with and without re-calibrating the film, the net optical density (NOD) for the red channel was fitted to the delivered dose using a power function27 across the four lots. The calculated film dose was then compared with the delivered dose.

According to the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology guidelines45, total standard uncertainty encompasses uncertainties from the experiment, fitting process, and deep learning process. The uncertainties associated with the experiment and fitting process were calculated using methods detailed by Chang et al.28. Uncertainty from the GANN process was assessed using Monte Carlo dropout46.

Results

The calibration results of three alternative approaches were compared with those of the new adaptive GANN technique using Eq. (7). These approaches include: using only the first calibration parameters A1, B1, C1, and D1 without further calibration; performing recalibration using An, Bn, Cn, and Dn as in Eq. (2); and using the adaptive method with A1, B1, C1, and ε in Eq. (6), where ε is − 0.002, 0.001, 0.000, and − 0.002 for lots C, G, H, and I, respectively.

For lot C, the second and third calibrations were conducted 240 and 430 days after the first, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates the calibration results for the four methods mentioned above. The new adaptive GANN method maintains percentage differences between calibrated and delivered doses within 5%, comparable to the results from both the adaptive process and the recalibration method using Eq. (2). In contrast, the percentage difference would exceed 50% if only the first calibration parameters were used.

The calculated film doses (DFn) for film Lot C are compared with the delivered doses (Dd) for different calibration days after the date of the first calibration using (1) the initial fitting parameters, A1, B1, C1 and D1 (red lines), (2) the fitting parameters that are recalibrated on the calibration date (green lines), (3) the adaptive method using Eq. 6 (cyan lines), and (4) the GANN method using Eq. 7 (blue lines).

For lot G, the second and third calibrations were conducted 100 and 260 days after the first. Figure 4 illustrates the calibration results for the four methods. With the new adaptive GANN method, percentage differences between calibrated and delivered doses are within 4%, closely matching the adaptive process results, whereas the recalibration method yields a difference within 3%. The percentage difference would exceed 10% if only the first calibration parameters were used.

The calculated film doses (DFn) for film Lot G are compared with the delivered doses (Dd) for different calibration days after the date of the first calibration using (1) the initial fitting parameters, A1, B1, C1 and D1 (red lines), (2) the fitting parameters that are recalibrated on the calibration date (green lines), (3) the adaptive method using Eq. 6 (cyan lines), and (4) the GANN method using Eq. 7 (blue lines).

Figure 5 illustrates the calibration results for lot H using the four methods; the second and third calibrations were conducted 240 and 420 days after the first. With the new adaptive GANN and recalibration methods, the percentage differences between the calibrated and delivered doses are within 3%, whereas the adaptive method alone results in differences up to 20%; using only the first calibration parameters leads to differences exceeding 50%.

The calculated film doses (DFn) for film Lot H are compared with the delivered doses (Dd) for different calibration days after the date of the first calibration using (1) the initial fitting parameters, A1, B1, C1 and D1 (red lines), (2) the fitting parameters that are recalibrated on the calibration date (green lines), (3) the adaptive method using Eq. 6 (cyan lines), and (4) the GANN method using Eq. 7 (blue lines).

For lot I, the second and third calibrations occurred 260 and 420 days after the first. The calibration results of the four methods are shown in Fig. 6. With the new adaptive GANN method, percentage differences between the calibrated and delivered doses are within 5%. The adaptive method yields percentage differences exceeding 5% for delivered doses below 100 cGy, while differences for the method using only the first calibration parameters exceed 20%. At 420 days, the adaptive and GANN methods produced a percentage difference comparable to that of the recalibration method, which is within 3%.

The calculated film doses (DFn) for film Lot I are compared with the delivered doses (Dd) for different calibration days after the date of the first calibration using (1) the initial fitting parameters, A1, B1, C1 and D1 (red lines), (2) the fitting parameters that are recalibrated on the calibration date (green lines), (3) the adaptive method using Eq. 6 (cyan lines), and (4) the GANN method using Eq. 7 (blue lines).

Calibration using the general NOD27 also showed large differences from the delivered dose. Figure 7 presents the calibration results for the four film lots using the first calibration parameters from the NOD calibration equation 250 days after the first calibration, along with results for the four film lots recalibrated on those dates using the NOD. Films receiving doses below 100 cGy exhibited greater differences, often exceeding 5%, primarily due to the aging effect21,22,23,24,25,26. In contrast, films with higher delivered doses had percentage differences below 5% when recalibrated.

Using the general net optical density, the percentage differences between the calibrated and the delivered doses of the four lots of film are calibrated around 250 days after the first calibration date. The dot marks and the cross marks are the differences using new recalibration and the first calibration parameters, respectively.

These findings demonstrate that it is preferable to recalibrate the film if several months have passed between the measurement and calibration dates. However, even with recalibration, differences between delivered and calculated doses remain high for low doses because EBT3 film requires two-axis non-uniformity correction47 for aged films unless calibrated using the three-channel technique28.

Table 1 presents the combined and standard uncertainties, including uncertainties from the experiment, fitting process, and GANN process. The uncertainty was averaged across all four lots, with a combined uncertainty of approximately 2%.

Discussion

Using the GANN technique for the four lots, the percentage differences between calculated and delivered doses were generally less than 5%, comparable to traditional recalibration methods19,48,49. One factor contributing to the 5% difference is fluctuations in relative humidity (RH)50, which ranged from 45 to 65% during our experiments and should be controlled in future studies. The uncertainty budget (Table 1) indicates that the combined uncertainty was approximately 2%, primarily due to measurement, fitting process, and GANN Monte Carlo dropout.

When analyzing the four film lots, a shorter interval between uses resulted in more accurate results using an adaptive Keras GANN. However, a longer calibration interval of 420 days did not necessarily lead to greater percentage differences (Fig. 6); the inherent properties of the film may be an essential factor. Compared to previous research that relied solely on adaptive methods, accuracy has improved. Most importantly, this method eliminates the need to identify a suitable ε, achieving a genuine one-time calibration. Subsequent calibrations can be fully customized for the same boxes of EBT3 films stored for years.

An adaptive Keras GANN can continue to improve by adjusting seed values, the number of layers and connections, and activation parameters, potentially yielding better results. Efforts can be made to provide low-dose training data and to test EBT3 films from different batches. Additionally, related deep learning techniques, such as self-segmentation learning, could be explored. For instance, while training the neural network model, optimal network connection weights could be stored using K-fold techniques. Finding appropriate methods requires time and effort. Because ε and τ are only related to the film’s optical density and background values, our calibration can be considered adaptive for each individual film and even each measurement point, providing a customized calibration design for each film. Future studies might consider bypassing optical density methods entirely by using pixel values or inverse transmittance directly with the adaptive Keras GANN method to calculate film doses, potentially yielding unexpectedly favorable results.

Our recent studies indicate several reasons for the high error rate in the general NOD method (Fig. 7). First, film aging causes significant differences in the radiochemical reactions of different EBT3 films, leading to greater variation in the power parameter. Films with lower doses may require separate calibration. Second, recent studies with EBT3 combined with Epson scanners have shown abnormally large errors at the film’s upper and lower edges47. The traditional three-channel method can provide some corrections for these errors, but the general NOD method requires additional correction47.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the adaptive GANN technique enhances film calibration. By incorporating a variable exponent and adapting the calibration parameter to each individual film and its background optical density, the GANN method consistently achieved percentage differences within 5% between calculated and delivered doses across multiple lots of EBT3 films, even after extended storage periods. This represents a substantial improvement over other methods, which often result in higher errors and require cumbersome repeated calibrations. The GANN approach eliminates the need for precise bias adjustment (ε), enabling robust and reliable calibration without ongoing recalibrations.

Furthermore, the findings underscore the potential for refining and optimizing the GANN technique to further enhance its accuracy and applicability. Future work could explore different neural network configurations, increase low-dose training data, and test films from various batches to broaden the technique’s generalizability. This adaptive method represents a significant advancement in film dosimetry, offering a more efficient, cost-effective, and precise calibration process. It paves the way for radiation therapy centers to adopt customized calibration methods tailored to their specific conditions, thereby improving treatment accuracy and patient outcomes.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data can be sent only by email.

References

Bentzen, S. M. & Gregoire, V. Molecular imaging-based dose painting: A novel paradigm for radiation therapy prescription. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 21, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semradonc.2010.10.001 (2011).

Arjomandy, B. et al. Energy dependence and dose response of Gafchromic EBT2 film over a wide range of photon, electron, and proton beam energies. Med. Phys. 37, 1942–1947 (2010).

Devic, S., Tomic, N. & Lewis, D. Reference radiochromic film dosimetry: Review of technical aspects. Phys. Med. 32, 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2016.02.008 (2016).

Perez Azorin, J. F., Ramos Garcia, L. I. & Marti-Climent, J. M. A method for multichannel dosimetry with EBT3 radiochromic films. Med. Phys. 41, 062101. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4871622 (2014).

Reinhardt, S., Hillbrand, M., Wilkens, J. J. & Assmann, W. Comparison of Gafchromic EBT2 and EBT3 films for clinical photon and proton beams. Med. Phys. 39, 5257–5262. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4737890 (2012).

Ohuchi, H. High sensitivity radiochromic film dosimetry using an optical common-mode rejection and a reflective-mode flatbed color scanner. Med. Phys. 34, 4207–4212 (2007).

Aland, T., Kairn, T. & Kenny, J. Evaluation of a Gafchromic EBT2 film dosimetry system for radiotherapy quality assurance. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 34, 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13246-011-0072-6 (2011).

Andres, C., del Castillo, A., Tortosa, R., Alonso, D. & Barquero, R. A comprehensive study of the Gafchromic EBT2 radiochromic film. A comparison with EBT. Med. Phys. 37, 6271–6278 (2010).

McCaw, T. J., Micka, J. A. & Dewerd, L. A. Characterizing the marker-dye correction for Gafchromic((R)) EBT2 film: A comparison of three analysis methods. Med. Phys. 38, 5771–5777. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3639997 (2011).

Devic, S., Tomic, N., Soares, C. G. & Podgorsak, E. B. Optimizing the dynamic range extension of a radiochromic film dosimetry system. Med. Phys. 36, 429–437 (2009).

Kairn, T., Aland, T. & Kenny, J. Local heterogeneities in early batches of EBT2 film: A suggested solution. Phys. Med. Biol. 55, L37-42. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/55/15/L02S0031-9155(10)56116-5[pii] (2010).

Richley, L., John, A. C., Coomber, H. & Fletcher, S. Evaluation and optimization of the new EBT2 radiochromic film dosimetry system for patient dose verification in radiotherapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 55, 2601–2617. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/55/9/012 (2010).

Hartmann, B., Martisikova, M. & Jakel, O. Homogeneity of Gafchromic EBT2 film. Med. Phys. 37, 1753–1756 (2010).

Chang, L. et al. The suitable dose range for the calibration of EBT2 film by the PDD method with a comparison of two curve fitting algorithms. Nuclear Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 777, 85–90 (2015).

Moylan, R., Aland, T. & Kairn, T. Dosimetric accuracy of Gafchromic EBT2 and EBT3 film for in vivo dosimetry. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 36, 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13246-013-0206-0 (2013).

Brown, T. A. et al. Dose-response curve of EBT, EBT2, and EBT3 radiochromic films to synchrotron-produced monochromatic x-ray beams. Med. Phys. 39, 7412–7417. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4767770 (2012).

Desroches, J., Bouchard, H. & Lacroix, F. Potential errors in optical density measurements due to scanning side in EBT and EBT2 Gafchromic film dosimetry. Med. Phys. 37, 1565–1570 (2010).

Lewis, D., Micke, A., Yu, X. & Chan, M. F. An efficient protocol for radiochromic film dosimetry combining calibration and measurement in a single scan. Med. Phys. 39, 6339–6350. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4754797 (2012).

Marroquin, E. Y., Herrera Gonzalez, J. A., Camacho Lopez, M. A., Barajas, J. E. & Garcia-Garduno, O. A. Evaluation of the uncertainty in an EBT3 film dosimetry system utilizing net optical density. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 17, 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.v17i5.6262 (2016).

Chang, L. et al. Calibration of the EBT3 gafchromic film using HNN deep learning. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 8838401. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8838401 (2021).

Chang, L. et al. An adaptive method for recalibrating Gafchromic EBT3 film. Nuclear Inst. Methods Phys. Res. A 1007, 1–6 (2021).

Sipila, P., Ojala, J., Kaijaluoto, S., Jokelainen, I. & Kosunen, A. Gafchromic EBT3 film dosimetry in electron beams—energy dependence and improved film read-out. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 17, 360–373. https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.v17i1.5970 (2016).

Dreindl, R., Georg, D. & Stock, M. Radiochromic film dosimetry: Considerations on precision and accuracy for EBT2 and EBT3 type films. Z. Med. Phys. 24, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zemedi.2013.08.002 (2014).

Feng, Y., Tiedje, H. F., Gagnon, K. & Fedosejevs, R. Spectral calibration of EBT3 and HD-V2 radiochromic film response at high dose using 20 MeV proton beams. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 89, 043511. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4996022 (2018).

Mathot, M., Sobczak, S. & Hoornaert, M. T. Gafchromic film dosimetry: Four years experience using FilmQA Pro software and Epson flatbed scanners. Phys. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2014.06.043 (2014).

Dal Col, A. H. et al. Issues on VMAT QA program with EBT3 radiochromic films: An improvement proposal. Rev. Bras. Fís. Méd. 12, 7–14 (2018).

Chang, L., Chui, C. S., Ding, H. J., Hwang, I. M. & Ho, S. Y. Calibration of EBT2 film by the PDD method with scanner non-uniformity correction. Phys. Med. Biol. 57, 5875–5887. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/57/18/5875 (2012).

Chang, L. et al. Calibration of EBT2 film using a red-channel PDD method in combination with a modified three-channel technique. Med. Phys. 42, 5838–5847. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4930253 (2015).

Zhuang, Y., Li, Y., Zhu, J., Chen, L. & Liu, X. A trial for EBT3 film without batch-specific calibration using a neural network. Phys. Med. Biol. 64, 05NT01. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/aafcbb (2019).

Ohno-Machado, L., Walker, M. G. & Musen, M. A. Hierarchical neural networks for survival analysis. Medinfo 8(Pt 1), 828–832 (1995).

Ferreira, B. C., Lopes, M. C. & Capela, M. Evaluation of an Epson flatbed scanner to read Gafchromic EBT films for radiation dosimetry. Phys. Med. Biol. 54, 1073–1085. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/54/4/017 (2009).

Chang, L., Ho, S. Y., Ding, H. J., Lee, T. F. & Chen, P. Y. Dependency of EBT2 film calibration curve on postirradiation time. Med. Phys. 41, 021726. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4862511 (2014).

Chang, L., Ho, S. Y., Ding, H. J., Yeh, S. A. & Chen, P. Y. Calibration of Gafchromic EBT film using the Microtek ScanMaker 9800XL plus flatbed scanner with a modified one red-channel after three-channel method. J. Med. Phys. 44, 207–212. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmp.JMP_45_19 (2019).

Chang, L. et al. Evaluation of multiple-sampling function used with a Microtek flatbed scanner for radiation dosimetry calibration of EBT2 film. Nuclear Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 832, 179–183 (2016).

Chang, L., Ho, S., Ding, H. J., Yeh, S. A. & Chen, P. Y. Calibration of gafchromic EBT film using the Microtek ScanMaker 9800XL plus flatbed scanner with a modified one red-channel after three-channel method. J. Med. Phys. 44, 207–212 (2019).

Klein, E. E. et al. Task Group 142 report: Quality assurance of medical accelerators. Med. Phys. 36, 4197–4212 (2009).

Kutcher, G. J. et al. Comprehensive QA for radiation oncology: Report of AAPM radiation therapy committee task group 40. Med. Phys. 21, 581–618 (1994).

Schulz, R. J. et al. A protocol for the determination of absorbed dose from high-energy photon and electron beams. Med. Phys. 10, 741–771 (1983).

Almond, P. R. et al. AAPM’s TG-51 protocol for clinical reference dosimetry of high-energy photon and electron beams. Med. Phys. 26, 1847–1870 (1999).

Hupe, O. & Brunzendorf, J. A novel method of radiochromic film dosimetry using a color scanner. Med. Phys. 33, 4085–4094 (2006).

Chiu-Tsao, S. T. & Chan, M. F. Photon beam dosimetry in the superficial buildup region using radiochromic EBT film stack. Med. Phys. 36, 2074–2083 (2009).

Nath, R. et al. AAPM code of practice for radiotherapy accelerators: Report of AAPM radiation therapy task group No. 45. Med. Phys. 21, 1093–1121 (1994).

Wang, L., Liu, X., Liang, H. & Carroll, R. J. Estimation and variable selection for generalized additive partial linear models. Ann. Stat. 39, 1827–1851. https://doi.org/10.1214/11-AOS885SUPP (2011).

Stone, C. J. Additive regression and other nonparametric models. Ann. Stat. 13, 689–705 (1985).

JCGM. Evaluation of measurement data—Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement. Joint Committee of Guides in Metrology 100:2008 (2008).

Gal, Y. & Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a Bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning vol. 48, 1050–1059 (2016).

Chang, L. Calibration of EBT3 film using an Epson 12000XL scanner with two-axes non-uniformity correction. Med. Phys. 50, e795. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.16525 (2023).

Dunn, L., Godwin, G., Hellyer, J. & Xu, X. A method for time-independent film dosimetry: Can we obtain accurate patient-specific QA results at any time postirradiation?. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 23, e13534. https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.13534 (2022).

Bouchard, H., Lacroix, F., Beaudoin, G., Carrier, J. F. & Kawrakow, I. On the characterization and uncertainty analysis of radiochromic film dosimetry. Med. Phys. 36, 1931–1946. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3121488 (2009).

Leon-Marroquin, E. Y. et al. Investigation of EBT3 radiochromic film’s response to humidity. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 19, 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.12337 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 109-2221-E-214-003, MOST 111-2221-E-214-019, and NSTC 113-2221-E-992-011-MY2). The authors thank Dr. Chien-Hua Chen for his assistance with programming.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. C. and S.-A.Y. carried out the experiment. L. C. and T.-F.L. wrote the manuscript with support from P.-Y. C., L.C., and C.-L. K. fabricated the experimental samples. C.-L. K. and C.-T. S. helped supervise the project. L .C. and P.-Y. C. conceived the original idea. T.-F. L. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, L., Chen, PY., Yeh, SA. et al. Adaptive calibration of Gafchromic EBT3 film using generalized additive neural networks. Sci Rep 15, 8208 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92568-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92568-7