Abstract

Although the 50-mile ultramarathon is one of the most common race distances, it has received little scientific attention. The objective of this study was to assess how an athlete’s age group, sex, nationality, and the race location, affect race speed. Utilizing a dataset with ultramarathon races from 1863 to 2022, a machine learning model based on the XGBoost algorithm was developed to predict the race speed based on the aforementioned variables. Model explainability tools, including model features relative importances and prediction distribution plots were then used to investigate how each feature affects the predicted race speed. The most important features, with respect to the predictive power of the XGBoost model, were the location of the race and the athlete’s gender. The top 3 countries with the fastest predicted median race speeds were Slovenia, New Zealand, and Bulgaria for nationality and New Zealand, Croatia, and Serbia for the race location. The fastest median race speed was predicted for the age group 20–24 years, but a marked age-related performance decline only became apparent from the age group 40–44 years onward. Model predictions for male athletes were faster than for female athletes. This study offers insights into factors influencing race speed in 50-mile ultramarathons, which may be beneficial for athletes, coaches, and race organizers. The identification of nationalities and event countries with fast race speeds provides a foundation for further exploration in the field of ultramarathon events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultrarunners participate in running events that exceed the 26.2-mile (42.195 km) marathon distance. The most common ultramarathon race distances are 50 km, 50 miles (80.467 km), 100 km, and 100 miles (160.934 km)1,2. Although the 50-mile ultramarathon is among the most prevalent race distances, there has been limited scientific interest considering 50-mile ultramarathoners or 50-mile ultramarathons2,3.

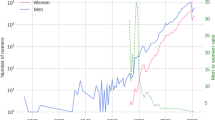

Age2, age-related performance4, and the sex difference in performance5,6,7 are aspects that were investigated before in 50-mile ultramarathoners. In the literature, a higher age of peak performance was observed in ultramarathons (~ 35 years and older) than in marathons (~ 25–35 years)2,8,9,10,11,12. In particular, Nikolaidis et al.13 examined data from 494,414 finishers who participated in 50-km ultramarathons from 1975 to 2016. When the top 10 athletes were analyzed, they found that men of the age 39 and women of the age 40 had the fastest mean running speeds. Similarly, in 50-mile races, men at the age of 35 and women at the age of 37 achieved the fastest running speeds2. In longer 100-km ultramarathons, men around 41 years old and women around 39 years old were the best in the top 109. Moreover, in even longer 100-mile ultramarathons, Rüst et al.12 reported that the mean age of the fastest men was 37.2 ± 6.1 years and that of the fastest women 39.2 ± 6.2 years.

The sex gap in endurance sports has been investigated extensively and it seems to depend on the race distance7,14. It has been suggested that female predispositions like improved resistance to fatigue, enhanced utilization of substrates, and reduced energy requirements could be advantageous in longer distances, but may only play a role in extreme endurance races14,15. Previously, Waldvogel et al.7 analyzed 50-mile and 100-mile ultramarathons and found a larger sex gap in mean race speed in the shorter 50-mile (9.13%) than in the 100-mile (4.41%) distance. Moreover, when Senefeld et al.16 investigated the top 10 finishers from 20 ultramarathons with a distance between 45 km and 160 km, they reported that the largest sex gap was observed in the shortest distance of 45–50 km (19.3% ± 5.8%). However, the sex differences in the 80-km (18.5 ± 6.0%) and the 100-km distance (14.9 ± 4.2%) were not smaller than in the 160-km distance (18.7 ± 5.1%)16. Furthermore, Knechtle et al.17 examined the sex gap in time-limited ultramarathons ranging from 6 to 240 h and concluded that women did not relatively better perform than men in events with longer race durations. A recently published systematic review that analyzed the literature for evidence regarding sex-specific guidelines for ultramarathoners and their coaches stated that further research is required to develop such guidelines as there is a lack of high-quality evidence3.

Regarding the origin of athletes, it is widely recognized that athletes from specific regions tend to perform better in particular sports. Looking at other endurance running distances, runners from Africa, especially East Africa, dominate worldwide long-distance events up to the marathon distance18,19,20,21,22. Regarding longer ultramarathon distances, only a few studies have analyzed the aspects of nationality on performance23,24,25. Knechtle et al.23 analyzed results from 150,710 finishers of 100-km ultramarathons and found that athletes from Russia and Hungary performed best. A recently published study by Thuany et al.24 on 100-mile ultramarathons with a dataset of 148,169 finishers found that women from Sweden, Hungary, and Russia and men from Brazil, Russia, and Lithuania had the fastest mean speeds in the top 3, top 10 and top 100 respectively. However, when the authors performed a macro-analysis by continent, African runners were the fastest, but their participation was very low. For 50-mile ultramarathons, however, we have no knowledge where the fastest runners were from and where the fastest races were held in the past. Knowledge about the dominance of athletes from specific regions may assist in selecting athletes for further investigation and understanding the factors behind their performance and endurance capabilities. Training26,27, motivation28, mood29, and nutrition30,31 have been investigated in ultrarunners to understand factors that influence performance. Additionally, research was also performed on medical aspects such as the influence on pain sensitivity32,33, the immune system34, skeletal muscles35, and the kidneys36. Such extensive research is justified by the physical demands and the concerns regarding the well-being and health status of athletes in both training and competition settings35,37.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship of an athlete’s age group, gender, nationality, and the location of the race, on race speed using an extensive dataset containing race records from 1863 to 2022 and a machine learning model based on the XGBoost algorithm. Knowledge about these aspects can help athletes and professionals working with ultramarathon runners.

Methods

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kanton St. Gallen, Switzerland, with a waiver of the requirement for informed consent of the participants as the study involved the analysis of publicly available data (EKSG 01/06/2010). The study was conducted in accordance with recognized ethical standards according to the Declaration of Helsinki adopted in 1964 and revised in 2013.

Study design, sample, and data preparation

For this cross-sectional study, secondary data from the official website of the ‘Deutsche Ultramarathon-Vereinigung’ was obtained38. Race results from athletes who competed in a 50-mile ultramarathon from 1863 until the end of 2022 were considered. Each race record included the athlete’s name, age group, gender, nationality, the race location and year, the race distance, and an athlete’s race time, from which the race speed was calculated in km per hour (km/h). In total, 341,188 race records were identified. We observed that the dataset was imbalanced, with Anglo-Saxon countries vastly dominating the sample, and the United States of America alone accounting for 82% of the sample. In contrast, there were also countries with only a small number of results from a few individual runners. To address these two issues, we discarded any race records from athlete countries with less than 15 records or less than 5 individual runners, any race records from event countries with less than 10 records, and down-sampled (randomly) the United States of America data to 10% of its full size.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented using mean ± standard deviation, minimum/maximum values, frequencies, and percentages. Machine learning was used because of its ability to handle non-linear, complex interactions between different variables, making it possible to reveal patterns that might not be evident using traditional statistical methods. We built and evaluated a predictive model for the 50-mile race distance based on the popular machine learning XGBoost regressor algorithm. This algorithm is available for free and can handle large datasets within reasonable computing times. It also supports some of the most powerful explainability tools, which becomes essential for understanding the factors that influence predictions. The following variables were used as predictors, or inputs to the model: Athlete_gender_ID, Age_group_ID, Athlete_country_ID, Event_country_ID. The predictors are numerically encoded versions of the four race record features used for analysis: the athlete’s gender, age group, nationality, and the country where the race took place (see detailed explanation in the section ‘Country Rankings and Numerical Encoding of Categorical Variables’). The predicted variable, or algorithm output, was the race speed (km/h). We calculated two model evaluation metrics, mean absolute error (MAE) and coefficient of determination (R2). Moreover, the model features relative importances and prediction distribution plots were computed and analyzed. In addition to the predictive model interpretability analysis, a set of descriptive target plot charts present the groups’ average (mean) speed (targets), helping to set expectations for the prediction charts.

Country rankings and numerical encoding of categorical variables

Before the data could be fit into the XGBoost model, the predictors had to be numerically encoded. The Athlete gender variable was encoded as female = 0 and male = 1. The Age group variable was already numerically encoded in 5-year age groups, with the exception of the age group 18, which represents runners under 20 years old, and the age group 75, which represents runners who are 75 years old and older. The Athlete country and Event country variables were encoded based on their position in the respective rankings by number of records (participation).

XGBoost model parameters and metrics

After several iterations and tests, the optimal XGBoost model parameters and accuracy scores were:

-

200 estimators (learners or trees).

-

Learning rate: 0.3.

-

R2 score: 0.21 (in-sample with 90,206 race records).

-

MAE: 1.24 km/h.

Results

After all processing, the final 50-mile sample consisted of 90,206 race records from 55,213 unique runners from 60 different countries who participated in races in 36 different countries between 1863 and 2022. A total of 20,481 race records were by women and 69,725 by men.

Athlete country and event country rankings

The two variables representing the nationality and the country where the race took place, were ranked independently by mean race speed (km/h). The fastest mean running speeds were obtained by athletes originating from Bulgaria, Slovenia, New Zealand, Croatia, and Ukraine (See Table 1 for details).

The fastest mean running speeds were achieved in races held in New Zealand, Serbia, Croatia, Spain, and Hungary (See Table 2 for details).

Evaluation metrics and features importances

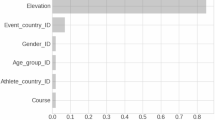

The model for the 50-mile race distance obtained a R2 of 0.21 which indicates an existing but weak effect of the predicting variables in the model output. Based on data entropy reduction, the model rated Event country (0.34) as the most important predictor, followed by Gender (0.33), Age group (0.17), and Athlete country (0.16).

Prediction distributions and target value plots

The following charts combine target value plots with prediction distribution plots. The target value plots provide a descriptive visualization of the 50-mile race sample, showing the average (mean) race speed (the target value) in red. The actual distribution of the XGBoost predictions of race speed is represented at the top of each figure in the form of boxplots, showing the median with the box spanning the interquartile range (IQR). The model interpretability chart for the feature age group also shows the number of records in each age group at the bottom (violet bars and boxes). The model interpretability charts for athlete and event country are sorted according to the number of race records, which are presented in detail in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. In general, the prediction distribution plots followed quite well the descriptive ranking tables. The age group 20–24 was the fastest, followed by age groups 25–29, 30–34, and 35–39, while most athletes were in the age group 40–44 (Fig. 1). In terms of nationality, Slovenia (10.28 km/h), New Zealand (10.09 km/h), and Bulgaria (9.87 km/h) had the fastest median predicted values (Fig. 2). For the event country predictor, New Zealand had the fastest median predicted value (10.75 km/h), followed by Croatia (9.80 km/h) and Serbia (9.53 km/h) (Fig. 3). Men were faster than women, with model predictions showing a median race speed around 0.6 km/h faster for males (median: 7.69 km/h, IQR: 0.3 km/h) than for females (median: 7.08 km/h, IQR: 0.2 km/h), with target values of 7.68 km/h and 7.08 km/h, respectively.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship of an athlete’s age group, sex, nationality, and the race location on race speed in 50-mile ultramarathons. The main findings according to the XGBoost model’s predictions were (i) model predictions were around 0.6 km/h faster for males than for females, (ii) the age group 20–24 was the fastest, whilst the age-related performance decline became more pronounced starting with age group 40–44, (iii) athletes from Slovenia, New Zealand, and Bulgaria had the fastest race speeds, (iv) across all races within each country, the fastest race speeds were found in New Zealand, Croatia, and Serbia, (v) the most important features with respect to the predictive power of the XGBoost model were the race location and an athlete’s gender.

The faster race speed of men is in accordance with past studies on ultramarathoners6,16 and other endurance sports39,40,41. Men had a median predicted race speed that was about 8.61% faster than the median predicted value for women. Previously, Waldvogel et al.7 reported a comparable mean difference in race speed of 9.13% between both sexes in 50-mile ultramarathons. However, Knechtle et al.17 found that women were able to narrow the performance difference between the sexes across most timed ultramarathons over the years. The main physiological factor for the performance sex gap in endurance sports is probably women’s lower aerobic capacity, which is often measured as maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max)42. The smaller sex gap in ultramarathons, compared to shorter race distances, can be explained by the fact that muscles are exercised at a lower percentage of VO2max15,42. Moreover, while females have a number of traits that are beneficial for ultramarathon running (e.g., increased resistance to muscle fatigue, higher reliance on lipid metabolism, and more even pacing strategies than men), certain aspects of female physiology still clearly hinder performance and reduce the likelihood that the fastest females will outperform the fastest males in longer ultramarathon events in the future14,43.

The age group 20–24 had the fastest predicted median race speed (8.01 km/h), closely followed by age groups 25–29 (7.93 km/h), 30–34 (7.83 km/h), and 35–39 (7.78 km/h). Thus, we found a younger age of peak performance in comparison to previous studies on ultramarathon finishers, which reported an age of peak performance of ~ 35 years and older2,9,12,13. However, a pronounced decline in performance was only observed from the age group 40–44 onward. One explanation could be that we have included data over a longer period of time. In past studies, an increase in the age of peak performance across the calendar years was observed in ultramarathons, as well as in other endurance sports13,44,45. Moreover, we used a different methodological approach and considered data from all finishers and did not only focus on the fastest finishers. The relatively increased performance of older athletes over the last decades in past studies on endurance sports is likely attributable to their higher training volume2,46. As athletes get older, they usually finish more half-marathons, marathons, and short ultramarathon races. With experience, they then tend to compete in longer distances, as a high training volume can better maintain endurance than sprint capacities due to various physiological aspects46,47,48. However, the decline in VO2max typically starts between the ages 20 and 3047. This may explain our finding that the model predicted the fastest race speeds for the age group 20–24 and challenges previous studies that used data over a shorter period.

The fastest median predicted race speeds were achieved by athletes from Slovenia (10.28 km/h), New Zealand (10.09 km/h) and Bulgaria (9.87 km/h). Following closely behind were athletes from Croatia (9.80 km/h) and Ukraine (9.61 km/h). It is noteworthy that the fastest runners mainly came from Eastern Europe, even though the participation in the sample was largely dominated by countries from the Anglosphere. One possible explanation for this trend might be attributed to the specific dataset characteristics. Many countries from Eastern European countries have fewer records in the dataset, potentially indicating a narrower overall range of performance levels. Professional athletes could be more willing to participate in ultramarathon events despite the expenses and various challenges. Amateur athletes frequently encounter real-life obligations and financial limitations49. This observation applies to all participants from countries far away from the race location, but it is especially remarkable in the case of Eastern Europe. For instance, Slovenia is ranked 23rd out of 50, Bulgaria is 36th, Croatia is 33rd, and Ukraine is 50th in the list of sovereign European countries by nominal gross domestic product per capita (in US$) in 2021 according to the World Bank, highlighting the ‘selectiveness’ of these professional athletes50. In our study, athletes from Africa, which as previously stated dominate running competitions worldwide up to the marathon distance, could not be included due to the too low rate of participation from these countries in the events analyzed18,19,20,21,22. One reason for their low participation is probably the lower prize money at ultramarathon events compared to marathon events, an important aspect, especially for elite athletes51,52.

The dominance of Anglo-Saxon countries in terms of overall participation and the number of events held can be attributed to various factors. Since our analysis specifically focused on the 50-mile distance and miles are the preferred unit of measurement in Anglo-Saxon countries, it is obvious that races of this distance have predominantly taken place in these regions and are not as popular in countries that do not use the imperial system. Moreover, the United States of America has been reported to be one of the birthplaces of ultramarathon, where a first running boom was seen in the 1960s24,53.

We found that the fastest median race speeds were predicted for 50-mile race courses held in New Zealand (10.75 km/h), followed by Croatia (9.80 km/h) and Serbia (9.53 km/h). As already mentioned above, athletes from New Zealand also had the second-fastest median predicted race speed. New Zealand has a long tradition of 50-mile races. The ‘New Brighton 50 Mile’ was held from 1962 to 1993 as a road-based race54. The ‘50 Miles Track Race Auckland’ was held from 1969 until 1972 and in the ‘Self-Transcendence’ races in Auckland and Christchurch, 50-mile split times were often recorded55,56. Other races such as the ‘Heaphy Five-0 Trail Run’ or the ‘The Old Forest Hanmer 100’57,58 were held as trail runs. However, as we used secondary data and a wide time frame, particular characteristics such as elevation profiles, weather conditions, and competitive environments could not be considered. Further explanations would be speculative and future studies should be carried out on this topic to understand the best conditions and characteristics for ultramarathon events, especially as the most important feature with respect to the XGBoost model’s predictive power was the race location.

Limitations, strengths, and implications for future research

In contrast to shorter endurance races, it is difficult to compare ultramarathon races as they are poorly standardized. To address this issue, we used a very large dataset and highly sophisticated data analysis techniques, but we must acknowledge some limitations. The results are a summary of the observations across the descriptive charts (i.e. target value plots) and ranking tables, as well as the model interpretability charts (prediction distribution plots). Athletes from countries with small sample sizes (less than 15 records or less than 5 individual runners), as well as records from event countries with fewer than 10 records but with faster race times, may have been excluded from the analysis due to the methodology used. Furthermore, reducing the USA data to 10% of its original size intended to prevent the predictive model from exhibiting a bias towards USA athlete race speeds, ensuring a more balanced analysis. Aspects such as physiological and anthropometric variables, training, previous experience, motivation, equipment, pre-race nutrition, nutrition during the race, elevation profiles, and environmental conditions could not be considered. As secondary data is used, we must also be aware that these race courses might not all have been exactly measured. Moreover, we did not differentiate between the sexes in our analysis regarding the fastest age group, nationality of the athletes, and location of the races. This could be a subject for future studies, which should also consider the use of a relative performance metric. The value of R2 (0.21) obtained with 200 estimators and a learning rate of 0.3 was the best we could get with the available data. This indicates an existing but weak effect of the predicting variables in the model output, acting as a reminder that if we want a better predictive model, we should look for additional features. In general, the prediction distribution plots followed quite well the descriptive ranking tables and charts, manifesting the ability of the machine learning model to learn the statistical structure of the data. A strength of the present study is its novelty, as it is one of the few studies to examine participation and performance trends in distance-limited ultramarathon races, and it is especially the first one on the 50-mile distance, using machine learning models. Moreover, our findings offer several practical applications for athletes and professionals working with ultramarathon runners competing at this distance. Identifying peak performance age groups and the onset of age-related performance decline provides valuable insights for data-driven career planning and realistic short- and long-term goal-setting. Additionally, information about locations with fast race times in the past can assist athletes and coaches in selecting races to achieve personal best performances while taking financial and travel considerations into account. It can also help race organizers to select or promote races that might be attractive for record attempts, which can increase participation and prestige. Future studies should analyze why faster race times are observed in certain locations and include more specific data such as the specific race courses.

Conclusions

In summary, this study used a machine learning algorithm to analyze 50-mile ultramarathon races, highlighting several important factors that influence race speed. The model predicted a faster median race speed for male ultramarathoners, and the fastest for athletes of the age group 20–24. The top 3 countries with the fastest predicted median race speeds with regard to nationality were Slovenia, New Zealand, and Bulgaria, and with regard to event location New Zealand, Croatia, and Serbia. The most significant variables in terms of the predictive power of the XGBoost model were the race location and an athlete’s gender.

Data availability

For this study, we have included official race results from the official DUV website (https://statistik.d-u-v.org). The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- km/h:

-

Kilometers per hour

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- R2 :

-

Coefficient of determination

- PDP:

-

Partial dependence plots

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- IOC:

-

International Olympic Committee (IOC) codes were used for different countries

References

Romer, T., Rüst, C. A., Zingg, M. A., Rosemann, T. & Knechtle, B. Age and ultra-marathon performance – 50 to 1,000 Km distances from 1969–2012. Springerplus 3, 693. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-693 (2014).

Zingg, M. A., Rüst, C. A., Rosemann, T., Lepers, R. & Knechtle, B. Runners in their forties dominate ultra-marathons from 50 to 3,100 Miles. Clin. (Sao Paulo). 69 (3), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2014(03)11 (2014).

Kelly, C. P. M. G. Is there evidence for the development of Sex-Specific guidelines for ultramarathon coaches and athletes?? A systematic review. Sports Med. Open. 9 (1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-022-00533-9 (2023).

Scheer, V. et al. Age-related participation and performance trends of children and adolescents in ultramarathon running. Res. Sports Med. 28 (4), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2020.1781124 (2020).

Sousa, C. V., da Silva Aguiar, S., Rosemann, T., Nikolaidis, P. T. & Knechtle, B. American masters road running records-the performance gap between female and male age group runners from 5 mm to 6 days running. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16 (13), 2310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132310 (2019).

Zingg, M. A., Knechtle, B., Rosemann, T. & Rüst, C. A. Performance differences between sexes in 50-mile to 3,100-mile ultramarathons. Open. Access. J. Sports Med. 6, 7–21. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S76490 (2015).

Waldvogel, K. J., Nikolaidis, P. T., Di Gangi, S., Rosemann, T. & Knechtle, B. Women reduce the performance difference to men with increasing age in ultra-marathon running. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16 (13), 2377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132377 (2019).

Lehto, N. Effects of age on marathon finishing time among male amateur runners in Stockholm marathon 1979–2014. J. Sport Health Sci. 5 (3), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2015.01.008 (2016).

Nikolaidis, P. T. & Knechtle, B. Performance in 100-km ultramarathoners-at which age, it reaches its peak? J. Strength. Cond Res. 34 (5), 1409–1415. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002539 (2020).

Zavorsky, G. S., Tomko, K. A. & Smoliga, J. M. Declines in marathon performance: sex differences in elite and recreational athletes. PLoS One. 12 (2), e0172121. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172121 (2017).

Lara, B., Salinero, J. J. & Del Coso, J. The relationship between age and running time in elite marathoners is u-shaped. Age (Dordr). 36 (2), 1003–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-013-9614-z (2014).

Rüst, C. A., Knechtle, B., Rosemann, T. & Lepers, R. Analysis of performance and age of the fastest 100-mile ultra-marathoners worldwide. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 68 (5), 605–611. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2013(05)05 (2013).

Nikolaidis, P. T. & Knechtle, B. Age of peak performance in 50-km ultramarathoners - is it older than in marathoners? Open. Access. J. Sports Med. 9, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S154816 (2018).

Tiller, N. B. et al. Do sex differences in physiology confer a female advantage in ultra-endurance sport? Sports Med. 51 (5), 895–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01417-2 (2021).

Hallam, L. C. & Amorim, F. T. Expanding the Gap: an updated look into sex differences in running performance. Front. Physiol. 12, 804149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.804149 (2022).

Senefeld, J., Smith, C. & Hunter, S. K. Sex differences in participation, performance, and age of ultramarathon runners. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 11 (7), 635–642. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2015-0418 (2016).

Knechtle, B. et al. Do women reduce the gap to men in ultra-marathon running? Springerplus 5(1), 672. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2326-y (2016).

Aschmann, A., Knechtle, B., Onywera, V. & Nikolaidis, P. T. Pacing strategies in the new York City marathon - does nationality of finishers matter? Asian J. Sports Med. 9 (2), e57596. https://doi.org/10.5812/asjsm.57596 (2018).

Knechtle, B., Rosemann, T. & Nikolaidis, P. T. The role of nationality in ultra-endurance sports: the paradigm of cross-country skiing and long-distance running. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (7), 2543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072543 (2020).

Knechtle, B. et al. Male and female Ethiopian and Kenyan runners are the fastest and the youngest in both half and full marathon. Springerplus 5, 223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-1915-0 (2016).

Tucker, R., Onywera, V. O. & Santos-Concejero, J. Analysis of the Kenyan distance-running phenomenon. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 10 (3), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2014-0247 (2015).

Vitti, A., Nikolaidis, P. T., Villiger, E., Onywera, V. & Knechtle, B. The new York City marathon: participation and performance trends of 1.2m runners during half-century. Res. Sports Med. 28 (1), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2019.1586705 (2020).

Knechtle, B., Nikolaidis, P. T. & Valeri, F. Russians are the fastest 100-km ultra-marathoners in the world. PLoS One 13 (7), e0199701. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199701 (2018).

Thuany, M. et al. A macro to micro analysis to understand performance in 100-mile ultra-marathons worldwide. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 1415. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28398-2 (2023).

Nikolaidis, P. T., Onywera, V. O. & Knechtle, B. Running performance, nationality, sex, and age in the 10-km, half-marathon, marathon, and the 100-km ultramarathon Iaaf 1999–2015. J. Strength. Cond Res. 31 (8), 2189–2207. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001687 (2017).

Thompson, W. R., Nequin, N. D., Lesmes, G. R. & Garfield, D. S. Physiological and training profiles of ultramarathoners. Phys. Sportsmed. 10 (5), 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.1982.11947223 (1982).

Nikolaidis, P. T. et al. Training and body composition during Preparation for a 48-hour ultra-marathon race: a case study of a master athlete. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16 (6), 903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060903 (2019).

Krouse, R. Z., Ransdell, L. B., Lucas, S. M. & Pritchard, M. E. Motivation, goal orientation, coaching, and training habits of women ultrarunners. J. Strength. Cond Res. 25 (10), 2835–2842. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318204caa0 (2011).

Burgum, P. & Smith, D. T. Reduced mood variability is associated with enhanced performance during ultrarunnning. PLoS One 16 (9), e0256888. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256888 (2021).

Mahon, E. A., Davies, I. G., Stott, T. A. & Hackett, A. F. Meeting carbohydrate recommendations during a mountain marathon. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 70 (OCE4), e231. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665111002825 (2011).

Costa, R. J. S., Knechtle, B., Tarnopolsky, M. & Hoffman, M. D. Nutrition for ultramarathon running: trail, track, and road. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 29 (2), 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0255 (2019).

Agnew, J. W., Roy, A. L., Hammer, S. B. & Strale, F. F. Pain sensitivity increases more in younger runners during an ultra-marathon. Scand. J. Pain 21 (2), 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2020-0032 (2021).

Agnew, J. W., Hammer, S. B., Roy, A. L. & Rahmoune, A. Central and peripheral pain sensitization during an ultra-marathon competition. Scand. J. Pain 18 (4), 703–709. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2018-0079 (2018).

Fukatsu, A., Sato, N. & Shimizu, H. 50-mile walking race suppresses neutrophil bactericidal function by inducing increases in cortisol and ketone bodies. Life Sci. 58 (25), 2337–2343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(96)00234-2 (1996).

Partyka, A. & Waśkiewicz, Z. The consequences of training and competition to the musculoskeletal system in ultramarathon runners: a narrative review. Front. Physiol. 12, 738665. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.738665 (2021).

Lipman, G. S. et al. Ibuprofen versus placebo effect on acute kidney injury in ultramarathons: a randomised controlled trial. Emerg. Med. J. 34 (10), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2016-206353 (2017).

Knechtle, B. & Nikolaidis, P. T. Physiology and pathophysiology in ultra-marathon running. Front. Physiol. 9, 634. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00634 (2018).

Deutsche Ultramarathon-Vereinigung. Ultra Marathon Statistics. https://statistik.d-u-v.org (Accessed 7 January 2024).

Knechtle, B., Rosemann, T., Lepers, R. & Rüst, C. A. Women outperform men in ultradistance swimming: the Manhattan Island marathon swim from 1983 to 2013. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 9 (6), 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2013-0375 (2014).

Lepers, R. Sex difference in triathlon performance. Front. Physiol. 10, 973. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00973 (2019).

Turnwald, J. et al. Participation and performance trends in short-, medium, and long-distance duathlon. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 9303. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36050-2 (2023).

Joyner, M. J. Physiological limits to endurance exercise performance: influence of sex. J. Physiol. 595 (9), 2949–2954. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP272268 (2017).

Hunter, S. K. et al. The biological basis of sex differences in athletic performance: consensus statement for the American college of sports medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 55 (12), 2328–2360. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000003300 (2023).

Knechtle, B., Valeri, F., Zingg, M. A., Rosemann, T. & Rüst, C. A. What is the age for the fastest ultra-marathon performance in time-limited races from 6 h to 10 days? Age (Dordr). 36 (5), 9715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-014-9715-3 (2014).

Gallmann, D., Knechtle, B., Rüst, C. A., Rosemann, T. & Lepers, R. Elite triathletes in ‘ironman Hawaii’ get older but faster. Age (Dordr). 36 (1), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-013-9534-y (2014).

Knechtle, B., Knechtle, P., Rosemann, T. & Lepers, R. Predictor variables for a 100-km race time in male ultra-marathoners. Percept. Mot Skills. 111 (3), 681–693. https://doi.org/10.2466/05.25.PMS.111.6.681-693 (2010).

Hawkins, S. & Wiswell, R. Rate and mechanism of maximal oxygen consumption decline with aging: implications for exercise training. Sports Med. 33 (12), 877–888. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200333120-00002 (2003).

Allen, S. V. & Hopkins, W. G. Age of peak competitive performance of elite athletes: a systematic review. Sports Med. 45 (10), 1431–1441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0354-3 (2015).

Lamont, M., Kennelly, M. & Wilson, E. Competing priorities as constraints in event travel careers. Tour Manag. 33 (5), 1068–1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.12.005 (2012).

World Bank. GDP per capita (current US$), data from database: world development indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/ (Accessed 7 January 2024).

Eichenberger, E. et al. The aspect of nationality and performance in a mountain ultra-marathon-the ‘swiss alpine marathon’. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 7 (4), 748–762. https://doi.org/10.4100/jhse.2012.74.03 (2012).

Onywera, V. O., Scott, R. A., Boit, M. K. & Pitsiladis, Y. P. Demographic characteristics of elite Kenyan endurance runners. J. Sports Sci. 24 (4), 415–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410500189033 (2006).

Noakes, T. D. The limits of endurance exercise. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 101 (5), 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-006-0607-2 (2006).

Deutsche Ultramarathon-Vereinigung. Ultra marathon statistics. Searching for event: New brighton 50 mile. https://statistik.d-u-v.org/search_event.php?sname=New+Brighton+50+Mile&Submit.x=23&Submit.y=5 (Accessed 7 January 2024).

Deutsche Ultramarathon-Vereinigung. Ultra marathon statistics. Searching for event: 50 miles track race auckland. https://statistik.d-u-v.org/search_event.php?sname=50+Miles+Track+Race+Auckland&Submit.x=17&Submit.y=10 (Accessed 7 January 2024).

Deutsche Ultramarathon-Vereinigung. Ultra marathon statistics. Searching for event: self-transcendence. https://statistik.d-u-v.org/search_event.php?sname=self-transcendence&Submit.x=0&Submit.y=0 (Accessed 7 January 2024).

Deutsche Ultramarathon-Vereinigung. Ultra marathon statistics. Searching for event: heaphy five-0 trail. https://statistik.d-u-v.org/search_event.php?sname=Heaphy+Five-0+Trail+Run&Submit.x=31&Submit.y=5 (Accessed 7 January 2024).

Deutsche Ultramarathon-Vereinigung. Ultra marathon statistics. Searching for event: the old forest hanmer 100. https://statistik.d-u-v.org/search_event.php?sname=The+Old+Forest+Hanmer+100&Submit.x=15&Submit.y=13 (Accessed 7 January 2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JT and BK drafted the manuscript, DV performed the statistical analysis and prepared methods and results, EV obtained the data, PF, KW, MT, VS, MW, MA, IC, and PN helped in drafting the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Turnwald, J., Valero, D., Forte, P. et al. Analysis of the 50-mile ultramarathon distance using a predictive XGBoost model. Sci Rep 15, 9016 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92581-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92581-w