Abstract

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and the risk of asthma in the pediatric population is not fully understood. This study aimed to investigate the association between BMI and asthma in a large nationally representative sample. The study included 35,603 pediatric participants from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2020. The association between BMI and asthma was examined using various statistical models, including logistic regression, piece-wise linear regression, and subgroup analyses, adjusting for potential confounding factors. When analyzing BMI as a continuous variable, a one-unit increase in BMI was associated with a 4% higher odds of asthma. A clear dose-response relationship was observed, where individuals in the higher BMI quartiles had progressively higher odds of asthma compared to those in the lowest quartile. Smooth curve fitting revealed a not entirely linear relationship, with a steeper increase in asthma risk at lower BMIs (below an inflection point of 21 kg/m²) compared to higher BMIs. Subgroup analyses consistently showed a positive association between BMI and asthma across different age, gender, race, socioeconomic, and smoking-related factors. Sensitivity analyses, including multiple imputation for missing data and alternative BMI metrics, confirmed the stability of the results. This study provides robust evidence for a positive and not entirely linear association between BMI and the risk of asthma in the pediatric population. These findings enhance the existing literature and underscore the necessity of considering BMI in both asthma research and clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by airway inflammation and narrowing, resulting in recurrent episodes of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing1. The prevalence of asthma varies across populations, with higher rates observed in urban and developed regions, such as 7.2% in the United States 2 and 4.2% in China3. Asthma is estimated to impact 262 million people, equating to an age-standardized prevalence rate of 3,416 cases per 100,000 individuals4. Exposure to triggers like allergens, respiratory infections, air pollutants, and occupational irritants can lead to airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in susceptible individuals5,6. The immune response is characterized by T-helper 2 (Th2) cell-mediated inflammation, involving the release of cytokines that promoting immunoglobulin (Ig) E production, eosinophil recruitment, and mucus secretion7. Early-life factors, including exposure to secondhand smoke, respiratory infections, and a family history of asthma or allergies contribute to asthma development8. Asthma treatment strategies involve a combination of medications, such as inhaled corticosteroids, bronchodilators, and leukotriene modifiers, tailored to the individual’s disease severity and triggers. Additionally, biological therapies have demonstrated promising results in severe, treatment-resistant asthma cases9,10.

Obesity is a complex, multifactorial chronic disease characterized by an excessive accumulation of body fat that poses significant health risks. The prevalence of obesity has surged globally, becoming a major public health concern linked to numerous comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers11. Obesity also contributes to impaired respiratory function, with evidence indicating a relationship between increased body weight and exacerbated respiratory conditions, such as asthma12. Obesity impacts asthma pathogenesis through various mechanisms, such as reducing immune tolerance by releasing pro-inflammatory mediators like IL-6, leptin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), thereby promoting asthma development13. Additionally, obesity may alter the clinical presentation of asthma by modifying airway inflammation, for instance, by decreasing the proportion of eosinophils14, and affecting lung mechanical properties15. Research has shown that obese individuals with asthma may exhibit more nonspecific inflammatory characteristics, such as neutrophilia16. Genetic studies suggest shared pathophysiological mechanisms between obesity and asthma, while a high-fat diet may also contribute to asthma development17. Obesity can also impact the efficacy of asthma treatment, particularly by reducing responsiveness to inhaled glucocorticoids18.

Body mass index (BMI) is the most widely used metric for evaluating the degree of obesity. While BMI can be readily calculated and measured to determine obesity in adults, defining overweight and obesity in children is more controversial19. Due to variations in classification methods and research approaches, prior studies on the association between obesity and asthma have sometimes yielded inconsistent findings19,20,21. Therefore, it remains necessary to examine the association between childhood BMI and asthma using large-scale data. This study employed the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2020 data on children and adolescents to perform a comprehensive analysis of the association between BMI and asthma, aiming to provide the latest robust evidence in this domain.

Methods and materials

Study population

NHANES, a program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), has been assessing the health and nutritional status of the American population since the early 1960s. NHANES employs a well-designed survey and sampling methodology to ensure national representation, collecting comprehensive data on diverse health indicators for both adults and children through in-depth interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests22. Eligible participants aged 16 and older were interviewed directly, while those under 16 were interviewed with a proxy. All participants who completed the household interview were invited to the Medical Examination component. This integrated approach has enabled NHANES to uncover critical insights into chronic diseases, dietary patterns, physical activity, and environmental exposures, informing evidence-based public health policies and clinical guidelines. The publicly available NHANES data serves as an invaluable resource for researchers investigating complex health phenomena and addressing pressing public health issues. Scholars can customize their data retrieval to align with their specific research objectives, selectively extracting relevant variables related to epidemiology, nutrition, and various other health metrics, while adhering to strict guidelines for data use and dissemination. For this study, we accessed data from the 1999–2020 NHANES cycles and collected demographic, examination, laboratory, and questionnaire data on relevant variables.

Body mass index

In NHANES, BMI data are derived from the body measurement section of the examination data. Body measurements are obtained through standardized procedures carried out by trained health technicians in specially equipped mobile examination centers. Height is measured using a stadiometer and weight is measured using a digital scale. These measurements follow strict protocols to ensure accuracy and consistency across survey participants. BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters, and NHANES provides BMI data for individuals aged 2 years and above.

Asthma

The assessment of asthma status in NHANES is typically based on responses to specific questionnaire items related to medical conditions. The presence of asthma is determined by the response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have/s/he has asthma?“. The NHANES website provides a more comprehensive description of the variables used to assess asthma.

Covariates

Based on a review of prior research23, the potential confounders for the current study included demographic and home environment factors: age, gender, race, poverty income ratio (PIR), and household smokers; as well as laboratory tests: serum lead, serum cadmium, and cotinine. PIR is defined as the ratio of household income to the poverty threshold. Previous studies have shown that children born in areas with higher proportions of low-income families, population density, and poverty have higher asthma prevalence rates24. The presence of a smoker in the home was determined by the participant’s response to the interview question, “Does anyone who lives here smoke cigarettes, cigars, or pipes anywhere inside this home?”. Cotinine, a major metabolite of nicotine, can be used as a marker of active smoking and an indicator of environmental tobacco smoke exposure, also known as “passive smoking”. Numerous studies have reported that exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, or “secondhand smoke,” increases the incidence and severity of asthma25,26. In addition, serum levels of lead, and cadmium have also been implicated in asthma, allergies, and other diseases27.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

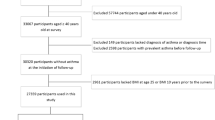

Individuals aged 2 to 19 years who answered yes or no to the asthma assessment questions and had BMI data were included in this study. Participants with missing data for any of the study variables were excluded.

Ethics statement

The human subjects used in this study were acquired from the NHANES protocol which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/). All participants or their legal guardians provided written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Appropriate sampling weights (NHANES MEC weights) were applied to the data to account for oversampling, nonresponse, and noncoverage, allowing for nationally representative estimates. Continuous variables were summarized as means ± standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as percentages. Participants were categorized into asthma and non-asthma groups based on the presence or absence of asthma. Weighted chi-square tests were used to calculate p-values for categorical variables, while weighted linear regression models were used for continuous variables. The association between BMI and asthma was evaluated using three logistic regression models. Model 1 was unadjusted, Model 2 was partially adjusted for age, gender, and race, and Model 3 was fully adjusted for all covariates, including age, gender, race, PIR, serum lead, serum cadmium, cotinine, and the presence of a smoker in the home. Trend tests were used to confirm the validity of the regression analysis results. Smooth curve fitting was employed to explore potential nonlinear relationships between BMI and asthma, and piecewise linear regression was used to analyze threshold effects if a nonlinear relationship was identified. The smooth curve fitting was conducted using generalize additive models. Stratified analyses by gender, age, race, PIR (trisection by percentage), cotinine (trisection by percentage), and the presence of smoker in the home were conducted to determine the association between BMI and asthma in specific subgroups. An interaction test was performed to assess whether individual characteristics influenced the association between BMI and asthma. Sensitivity analyses were performed using several approaches: BMI with 1% lowest and 1% highest values removed, BMI quintiles, and BMI z-score. A p-value less than 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant. In addition, in order to maximize statistical power and minimize bias, we also used the chained equation method based on 5 repetitions and the R MI procedure to compute missing data for missing values of covariates. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software R and EmpowerStats software.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Out of 107,622 NHANES participants enrolled from 1999 to 2020, 35,603 pediatric participants were included in the present study, as illustrated in the participant screening flowchart (Fig. 1).

Table 1 presents the weighted basic characteristics of participants categorized by their asthma status. Participants with asthma had a significantly higher mean age of 11.59 ± 4.67 years compared to those without asthma, who had a mean age of 10.97 ± 4.89 years (p < 0.001). The gender distribution also differed significantly between the two groups, with a greater percentage of males in the asthma group than the non-asthma group (56.76% vs. 49.59%, p < 0.001). Significant differences were observed in racial demographics, lead, cadmium, cotinine, and the presence of smokers in the home (all p < 0.001). However, no significant disparities were found in PIR between the two groups.

Association between BMI and asthma

The current study examined the association between BMI and the risk of asthma using various statistical models (Table 2). When analyzing BMI as a continuous variable, the results consistently showed a significant positive association across all models. Specifically, a one-unit increase in BMI was associated with a 4% higher odds of asthma in Model 1 (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03–1.04, p < 0.001), and this association remained unchanged after adjusting for demographics in Model 2 (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.04–1.04, p < 0.001). Further adjusting for additional confounding factors was made in Model 3 (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04, p < 0.001). The analysis based on BMI quartiles revealed a clear dose-response relationship, where individuals in the higher BMI quartiles had progressively higher odds of asthma. Compared to those in the first quartile (Q1), participants in the second (Q2), third (Q3), and fourth (Q4) quartiles had 25%, 49%, and 85% increased odds of asthma, respectively, in the non-adjusted model. This trend remained statistically significant across all three models (p for trend < 0.001).

Smooth curve fitting revealed that the relationship between BMI and asthma was not entirely linear after adjusting for relevant confounders (Fig. 2). Table 3 demonstrates the results of the piece-wise linear regression analysis, which identified an inflection point at a BMI of 21 kg/m2. Below this inflection point, the odds ratio for asthma was markedly higher (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.07–1.12, p < 0.001), indicating a steeper increase in asthma risk at lower BMIs. In contrast, above the inflection point, the odds ratio decreased (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.03, p < 0.001), suggesting a weaker association between BMI and asthma in higher BMI ranges.

Subgroup analysis

To further explore the relationship between BMI and asthma risk, a comprehensive subgroup analysis was conducted, adjusting for a range of potential confounding factors (Fig. 3). Our analysis revealed a consistent positive association between BMI and asthma across all examined subgroups, with ORs ranging from 1.025 to 1.059. Stratified by age, the association was stronger in participants aged ≤ 11 years (OR = 1.06, 95%CI: 1.05, 1.07) compared to those > 11 years (OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 1.02, 1.03), with a statistically significant interaction (p < 0.001). The subgroup analyses, stratified by gender, race, poverty income ratio, cotinine levels, and the presence of smoker in the home, all showed consistent positive associations between BMI and asthma.

Sensitivity analyses

Of the 35603 cases, 25452 (71.5%) had complete data for all variables. The amount of missing data was counted for each covariate and the results are displayed in Table S1. No covariates had a missing amount of more than 30%. in order to maximize statistical power and minimize bias, we also used the chained equation method based on 5 repetitions and the R MI procedure to compute missing data for missing values of covariates. The result of a fully adjusted regression analysis on the dataset obtained by multiple interpolation estimation (OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 1.03, 1.04), P < 0.001)) showed similar result to that with complete cases data. The association between asthma and BMI was further examined using BMI quintiles, BMI z-score, BMI with 1% lowest and 1% highest values removed. The results, presented in Table S2, showed that BMI quintiles, BMI z-score, and BMI with extreme values removed remained significantly and positively associated with asthma across different regression models. Additionally, a smoothed curve fitting analysis was conducted using BMI with 1% lowest and 1% highest values removed. The result, shown in Figure S1, remained not entirely linear. Piece-wise linear regression analysis identified an inflection point of 20.9 kg/m2, as presented in Table S2. In summary, the sensitivity analyses confirmed the stability of the results and the not entirely linear positive correlation between BMI and asthma.

Discussion

The study investigated the correlation between BMI and asthma in children, utilizing data from NHANES spanning 1999 to 2020. Our findings demonstrate a significant positive correlation between BMI and the risk of asthma. This relationship was consistent across different statistical models and remained significant after adjusting for demographic factors and potential confounders. Notably, a not entirely linear relationship was identified, with an inflection point at a BMI of 21 kg/m². Below this inflection point, the odds ratio for asthma was markedly higher (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.07–1.12, p < 0.001), indicating a steeper increase in asthma risk at lower BMIs. In contrast, above the inflection point, the odds ratio decreased (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.03, p < 0.001), suggesting a weaker association between BMI and asthma in higher BMI ranges. The comprehensive subgroup analysis, adjusting for potential confounding factors, revealed a consistent positive association between BMI and asthma across all examined subgroups. The result underscores the uniformity of this relationship across diverse demographic and environmental subgroups, suggesting the observed association is generalizable.

The concurrent rise in childhood obesity and asthma prevalence has become a significant public health concern, prompting an urgent need to understand their interplay28. As obesity is often measured by BMI, this research delves into the relationship between BMI and asthma risk in pediatric populations. The findings are consistent with several studies that have reported similar observations23,29. In our study, this association was observed across different logistic regression models, showing that each unit increase in BMI was associated with a 3 − 4% increase in the odds of developing asthma. This trend persisted even after adjusting for demographic factors and potential confounders. However, a study by Guibas et al. found BMI may not be as effective an indicator in preschool children, highlighting the complexity of the relationship and the need for age-specific assessment19.

While BMI has been widely adopted as a practical tool for identifying overweight and obesity in children and adolescents, it has limitations. It is a relative measure that does not account for differences in muscle mass, bone density, and overall body composition30. Moreover, BMI does not distinguish between fat-free mass and fat mass, which can be problematic when assessing obesity in children, given their ongoing growth and development31. Additionally, the use of BMI percentiles based on population data may not be universally applicable across different countries and regions due to variations in growth patterns and standards of living32. Relying solely on BMI can also neglect other crucial factors such as diet, physical activity, and genetic predispositions that contribute to obesity and related health risks33. Therefore, this study examines BMI as a continuous variable to reduce the impact of different categorization methods on the accuracy of the results.

Our analysis revealed a not entirely linear association between BMI and asthma, identified through smoothed curve fitting. A segmented linear regression model showed a threshold effect, with an inflection point at a BMI of 21 kg/m². This indicates a steeper increase in asthma risk at lower BMIs and a weaker association as BMI rises beyond this threshold, a finding not previously reported. Interestingly, a prospective study by Ulrik et al. emphasizes a similar nonlinear link between childhood BMI and asthma admissions in early adulthood, with gender-specific associations34. For females, a higher childhood BMI is linked to increased asthma admission risks, while in males, it is the lower BMI category that is associated with greater risks in early adulthood34. This finding challenges the conventional understanding of the obesity-asthma link, suggesting that both ends of the BMI spectrum may confer different risks for asthma severity, and these risks are modulated by gender. But there is also evidence suggesting that obesity in childhood and adulthood is an independent risk factor for asthma at each of the corresponding time points in its life course35. In summary, these findings suggest a more complex relationship between BMI and asthma. The age-stratified analysis revealed a statistically significant interaction, with a stronger association between BMI and asthma in participants aged ≤ 11 years compared to those > 11 years. This suggests that BMI may have a more pronounced impact on asthma risk during early childhood. Potential explanations include the critical period of immune and pulmonary development in younger children, during which adiposity-related inflammation and metabolic dysregulation may significantly influence airway hyperresponsiveness and asthma pathogenesis36,37. Although our study did not stratify by gender within age groups, existing evidence indicates that prepubertal boys may be more susceptible to the effects of adiposity on asthma risk, possibly due to differences in airway geometry and hormonal factors38,39. The weaker association in older children may reflect the modulating effects of pubertal hormonal changes on the relationship between adiposity and asthma40. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying this age-dependent association. The comprehensive subgroup analysis, adjusting for potential confounding factors, revealed a consistent positive association between BMI and asthma across all examined subgroups. The result underscores the uniformity of this relationship across diverse demographic and environmental factors.

However, our study has its limitations. The cross-sectional nature of our research restricts our ability to establish causality between BMI and asthma. Additionally, reliance on self-reported or proxy-reported data for asthma diagnosis could introduce bias, potentially impacting the accuracy of our estimates. The use of BMI as an adiposity measure is also a limitation, as it does not differentiate between fat and lean mass, which may have distinct associations with asthma36. The potential role of adipose tissue distribution, particularly central obesity37, which could be more relevant to asthma risk, was not directly evaluated in our study. Moreover, our analysis did not consider all possible confounding factors, such as diet, physical activity, sleep patterns, and genetic predispositions, that could affect the BMI-asthma relationship. The generalizability of our findings is further constrained by the predominantly Caucasian demographic of our sample, as the prevalence and relationship between obesity and asthma may differ among diverse racial and ethnic groups, suggesting that our results may not be universally applicable. Smooth curve fitting and inflection point testing were not conducted separately for subgroups such as boys and girls or younger and older children, which limits our ability to determine whether the observed not entirely linear association between BMI and asthma risk varies across these groups. Future studies with larger sample sizes and more detailed phenotypic characterization are needed to explore these potential subgroup differences.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study confirms a significant positive and not entirely linear association between BMI and the risk of asthma in children. Despite the robustness of our findings, the study’s limitations, including its cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported data, warrant further investigation. Future research should utilize longitudinal approaches and incorporate a wider array of obesity metrics, alongside lifestyle and genetic factors, to enhance our comprehension of this relationship. Our study’s results enhance the existing literature by providing a comprehensive understanding of the BMI-asthma relationship in pediatric populations, underscoring the necessity of considering BMI in both asthma research and clinical practice.

Data availability

The study data were derived from NHANES which can be freely obtained online (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Kuruvilla, M. E., Vanijcharoenkarn, K., Shih, J. A. & Lee, F. E. Epidemiology and risk factors for asthma. Respir Med. 149, 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2019.01.014 (2019).

Pate, C. A. & Zahran, H. S. The status of asthma in the united States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 21, E53. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd21.240005 (2024).

Huang, K. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of asthma in China: a National cross-sectional study. Lancet 394, 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31147-x (2019).

Global burden of 369. diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30925-9

Aghapour, M. et al. Role of air pollutants in airway epithelial barrier dysfunction in asthma and COPD. Eur. Respir Rev. 31 https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0112-2021 (2022).

Rasmussen, S. M. et al. Asthma endotypes in elite athletes: A cross-sectional study of European athletes participating in the olympic games. Allergy 77, 2250–2253. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.15313 (2022).

Noval Rivas, M. & Chatila, T. A. Regulatory T cells in allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138, 639–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.003 (2016).

Karmaus, W. et al. Long-term effects of breastfeeding, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and recurrent lower respiratory tract infections on asthma in children. J. Asthma. 45, 688–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770900802178306 (2008).

Kyriakopoulos, C., Gogali, A., Markozannes, G. & Kostikas, K. Biologic agents licensed for severe asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. Respir Rev. 33 https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0238-2023 (2024).

Bilò, M. B. et al. Severe asthma management in the era of biologics: insights of the Italian registry on severe asthma (IRSA). Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 53, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.23822/EurAnnACI.1764-1489.196 (2021).

Guh, D. P. et al. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public. Health. 9, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-88 (2009).

Yang, W. et al. Obesity and risk for respiratory diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1197730. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1197730 (2023).

Qin, Z. et al. Obesity alters inflammatory response in the pathology of asthma (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 52 https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2023.5266 (2023).

Sharma, V., Ricketts, H. C., Steffensen, F., Goodfellow, A. & Cowan, D. C. Obesity affects type 2 biomarker levels in asthma. J. Asthma. 60, 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2022.2051548 (2023).

Bates, J. H. & Dixon, A. E. Potential role of the airway wall in the asthma of obesity. J. Appl. Physiol. 118, 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00684.2014 (2015).

Vezir, E. et al. Effects of obesity on airway and systemic inflammation in asthmatic children. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 182, 679–689. https://doi.org/10.1159/000513809 (2021).

Dixon, A. E. & Poynter, M. E. A common pathway to obesity and allergic asthma. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 191, 721–722. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201502-0217ED (2015).

Peerboom, S. et al. Predictors of a good response to inhaled corticosteroids in obesity-associated asthma. Biochem. Pharmacol. 179, 113994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113994 (2020).

Guibas, G. V. et al. The obesity-asthma link in different ages and the role of body mass index in its investigation: findings from the genesis and healthy growth studies. Allergy 68, 1298–1305. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12245 (2013).

Wadden, D., Allwood Newhook, L. A., Twells, L., Farrell, J. & Gao, Z. Sex-Specific Association between Childhood BMI Trajectories and Asthma Phenotypes. Int J Pediatr 9057435, (2018). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9057435 (2018).

Au Yeung, S. L., Li, A. M. & Schooling, C. M. A life course approach to elucidate the role of adiposity in asthma risk: evidence from a Mendelian randomisation study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 75, 277–281. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-213745 (2021).

Swed, S. et al. Asthma prevalence among united States population insights from NHANES data analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 8059. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58429-5 (2024).

Visness, C. M. et al. Association of childhood obesity with atopic and nonatopic asthma: results from the National health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2006. J. Asthma. 47, 822–829. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2010.489388 (2010).

Zanobetti, A. et al. Childhood asthma incidence, early and persistent wheeze, and neighborhood socioeconomic factors in the ECHO/CREW consortium. JAMA Pediatr. 176, 759–767. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.1446 (2022).

Kaviany, P. et al. Spatial analysis of tobacco outlet density on secondhand smoke exposure and asthma health among children in Baltimore City. Tob. Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056878 (2022).

Johansson, E. et al. Second-hand smoke and NFE2L2 genotype interaction increases paediatric asthma risk and severity. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 51, 801–810. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.13815 (2021).

Zahedi, A. et al. Increased allergic and asthmatic risks in children residing in industrial areas by surveying the pre-inflammatory (IgE, IL-4 and IL-13) biomarkers. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 20, 609–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40201-021-00646-5 (2022).

Bantulà, M., Roca-Ferrer, J., Arismendi, E. & Picado, C. Asthma and obesity: two diseases on the rise and bridged by inflammation. J. Clin. Med. 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10020169 (2021).

Mitchell, E. A. et al. The association between BMI, vigorous physical activity and television viewing and the risk of symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema in children and adolescents: ISAAC phase three. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 43, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12024 (2013).

Javed, A. et al. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Obes. 10, 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.242 (2015).

Weber, D. R., Leonard, M. B., Shults, J. & Zemel, B. S. A comparison of fat and lean body mass index to BMI for the identification of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 3208–3216. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1684 (2014).

Ma, J., Wang, Z., Song, Y., Hu, P. & Zhang, B. BMI percentile curves for Chinese children aged 7–18 years, in comparison with the WHO and the US centers for disease control and prevention references. Public Health. Nutr. 13, 1990–1996. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980010000492 (2010).

Mishra, K. & Floegel-Shetty, A. What’s wrong with overreliance on BMI? AMA J. Ethics. 25, E469–471. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2023.469 (2023).

Ulrik, C. S., Lophaven, S. N., Andersen, Z. J., Sørensen, T. I. & Baker, J. L. BMI at school age and incident asthma admissions in early adulthood: a prospective study of 310,211 children. Clin. Epidemiol. 10, 605–612. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S156310 (2018).

Urquijo, H., Leyden, G. M., Davey Smith, G. & Richardson, T. G. A lifecourse Mendelian randomization study uncovers age-dependent effects of adiposity on asthma risk. iScience 26, 108356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108356 (2023).

Lang, J. E. Obesity and asthma in children: current and future therapeutic options. Paediatr. Drugs. 16, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-014-0069-1 (2014).

Gonzalez-Barcala, F. J. et al. Obesity and asthma: an association modified by age. Allergol. Immunopathol. 41, 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aller.2012.05.011 (2013).

Lang, J. E. et al. Being overweight or obese and the development of asthma. Pediatrics 142 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2119 (2018).

Rzehak, P. et al. Body mass index trajectory classes and incident asthma in childhood: results from 8 European birth Cohorts–a global allergy and asthma European network initiative. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131, 1528–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.001 (2013).

Wei, J. et al. Hormonal factors and incident asthma and allergic rhinitis during puberty in girls. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 115, 21–27e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2015.04.019 (2015).

Weber, D. R., Moore, R. H., Leonard, M. B. & Zemel, B. S. Fat and lean BMI reference curves in children and adolescents and their utility in identifying excess adiposity compared with BMI and percentage body fat. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.053611 (2013).

Kim, Y. et al. Additive effect of obesity and dyslipidemia on wheezing in Korean adults: A nationwide representative survey study. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 13, 808–816. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2021.13.5.808 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Ali Cao for providing invaluable guidance on the research design and statistical analysis.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XS and WF contributed to the study design and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. CF and JZ contributed to the data collection. CF, JZ and WF contributed to the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, C., Jiang, Z., Su, X. et al. The association between body mass index and asthma in children: a cross‑sectional study from NHANES 1999 to 2020. Sci Rep 15, 9448 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92619-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92619-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Obesity as the predominant contributor to asthma burden: insights from GBD and NHANES analyses

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

Nonlinear association between neutrophil percentage to high-density lipoprotein ratio and asthma in older population: a cross-sectional study

The Egyptian Journal of Bronchology (2025)

-

Positive association between visceral adiposity index and asthma in US children and adolescents: an analysis of NHANES data

Pediatric Research (2025)