Abstract

Peatlands are vital for global carbon storage, but drainage significantly disrupts their natural carbon cycling. Drainage alters peatland soil environments in complex ways, affecting factors such as water table, soil temperature, organic carbon (SOC), pH, and microbial communities. However, how these factors interact to influence GHG emissions remains unclear. In this study, we compared water table, soil temperature, soil properties, microbial community structure, and GHG emissions across three zones of a peatland in Northeast China undergoing drainage: drained, transition, and natural areas. The average water table in the drained area was significantly lower than in the natural area (from 11.45 cm to -13.47 cm), shifting from waterlogged to unsaturated conditions. Deep soil temperatures in the drained area decreased by 1 ~ 3 °C. The pH of the upper soil layer was higher in the drained area (5.05 ~ 5.29 vs. 4.64 ~ 4.71), while SOC was lower (197.31 ~ 374.75 g/kg vs. 437.05 ~ 512.71 g/kg). Aerobic bacteria (mainly Solibacter) were more abundant in the drained area, while methanogens (mainly hydrogenotrophic) declined significantly. Fungal diversity increased from the natural to drained area with increased negative interactions and enhanced network modularity. Drainage reduced CH4 emissions but increased CO2 and N2O emissions, resulting in a significant rise in net GHG emissions (8.86 ~ 10.65 vs. 22.27 ~ 24.26 t CO2-eq·ha⁻¹·season⁻¹), primarily driven by increased CO2. CO2 emissions were positively correlated with soil temperature, aerobic bacteria, facultatively anaerobic bacteria and pH, but negatively correlated with water table, anaerobic bacteria, soil moisture and C/N ratio. CH4 flux was positively correlated with methanogens and water table, but negatively correlated with pH. The effects of drainage were more pronounced near drainage ditches, particularly for CO2 emissions, highlighting the localized impacts of drainage on peatland GHG fluxes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peatlands, though covering only about 3% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface, play a pivotal role in the global carbon cycles1,2. They store approximately 644 Gt C, constituting 21% of the global soil carbon pool, and reserve 8 ~ 15 Gt N3,4,5, significantly contributing to climate change mitigation6,7. However, drained peatland can lead to the loss of this function and even shift from carbon sinks to carbon sources8. Currently, approximately 15% of the world’s peatlands are artificially drained for purposes such as agriculture, forestry, peat extraction, and bioenergy plantations9. Peatland drainage creates oxic conditions and accelerates the mineralization of organic matter and nitrogen, leading to soil environmental changes and, consequently, increased GHG emissions10. It has been estimated that the world’s drained peatlands cumulatively release 80.8 Gt C and 2.3 Gt N5. The impact of drainage on peatland soil environments (including water table, soil temperature, soil SOC, pH, and microbial community structure) and how these environmental changes influence GHG emissions, has attracted extensive scientific attention and promoted a series of studies on this topic.

The water level changes in peatlands caused by drainage are considered the primary reason for the decline in the climate regulation function of peatlands11. The biogeochemistry of peatlands is highly sensitive to hydrological regimes. Previous studies have found that, in most cases, higher water tables reduce CO2 emissions but increase CH4 emissions; while lower water tables accelerate carbon mineralization, leading to increased CO2 release and decreased CH4 flux12. However, some studies have observed weak or even opposite relationships between GHG emissions and the water table13,14,15,16. The inconsistent results may be attributed to the fact that changes in GHG emissions in drained peatlands are influenced not only by variations in the water table but also by factors such as soil temperature, physicochemical properties, and their interactions. Therefore, more research is needed to investigate the relationship between the drained peatland soil environment and changes in GHG emissions to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Soil temperature, as a key factor influencing nearly all biochemical reactions, directly affects the rates of soil respiration, mineralization, and methanogenesis17. Temperature correlations with CO2 and CH4 emission fluxes have been observed across a wide range of wetland ecosystems, consistent with kinetic predictions18,19,20,21. Soil temperature and environmental changes have also been shown to significantly affect N2O emissions from peatlands. Yi et al. (2023) found that increased soil temperature stimulates enzyme activity and alters soil stoichiometry, thereby increasing N2O emissions, even turning peatlands into a significant source of N2O22. Moreover, soil temperature and its effects have been shown to be regulated by water table, with the water table influencing the temperature sensitivity of GHG emissions7,23,24. Changes in soil physicochemical properties and microbial communities are also important factors driving variations in GHG emissions from drained peatlands. The decline in water table can result in increased soil aeration, altering soil pH, SOC, and nutrient cycling processes25. These changes in soil properties can, in turn, influence microbial activity26 and the decomposition of organic matter, leading to shifts in GHG emissions27. Drainage alters the redox conditions in peatland soils, which further leads to changes in SOC content and bioavailability in the soils. SOC content and labile fractions in the soils determine the quality of peatland soils and provide carbon sources and electron donors for methanogenesis. It has been observed that poor soil quality, such as the prevalence of recalcitrant organic materials, is more likely to result in low CH4 emission rates in peatland28,29,30. Drainage also affects the abundance of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, as well as methanogens, thereby influencing changes in CO2 and CH4 emission fluxes. It is generally recognized that undisturbed natural peatlands emit lower N2O due to nitrogen and phosphorus limitations22,31. However, under the background of climate change and human activities, changes in water table, soil temperature and soil properties in peatlands may significantly increase nitrous oxide emissions31,32,33.

Northeast China is one of the largest peatland area in China and holds a large carbon pool34,35 that accounts for 48% of the total area of wetlands in China36. At the same time, Northeast China has long been a key grain-producing region, resulting in a significant number of peatlands being impacted by agricultural activities, especially drainage practices37,38,39,40,41,42. However, there is currently no clear consensus on how drainage in Northeast China’s peatlands affects soil environment including water table, soil temperature, soil properties, and microbial communities, and how these factors interact to ultimately influence GHG emissions from these peatlands. Studying the impact of peatland drainage on GHG emissions and the underlying mechanisms is crucial for advancing the scientific restoration and management of peatland drainage activities, reducing GHG emissions, and mitigating the impact on global climate change. The hypothesis of this study is that drainage alters soil environments and microbial communities in peatlands, thereby affecting GHG emissions. Specifically, the lowering of the water table resulting from drainage may alter soil temperature, and change the SOC content, pH, and microbial community structure, leading to an increase in CO2 emissions, a reduction in CH4 emissions, and changes in N2O emissions. The objectives of this study are: (1) evaluateing the impacts of drainage on the soil environment of peatlands in Northeast China, with a particular focus on the water table, soil temperature, soil properties, and microbial community structure; (2) to explore how these factors interact and influence GHG emissions; and (3) to compare the GHG emissions across drained, transition and natural areas in peatlands, revealing the localized impacts of drainage on peatland GHG fluxes.

Study site and experimental set-up

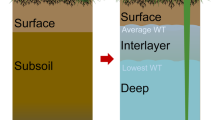

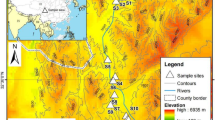

The study site, Jinchuan Peatland (42°20′56″ N, 126°22′51″ E) is located in Jinchuan Town, Huinan County, Jilin Province. It is part of the Longwan National Nature Reserve within the Changbai Mountain Range in Northeast China (Fig. 1a and b). Jinchuan Peatland covers a total area of approximately 100 hectares, with a peat layer thickness ranging from 3 to 9 m, experiences a temperate continental monsoon climate, with an annual average temperature of 4.1℃ and an average annual precipitation of 704.2 mm (Fig. S1). The dominated vegetation community types in the Jinchuan peatland are Sphagnum + Carex + Phragmites43,44,45. In the 1970s, to meet the growing demand for food, agricultural ditches were excavated around the periphery of Jinchuan Peatland, converting approximately 37 hectares of its edge area into reclaimed rice paddy peatland (Fig. 1c). As a result, the existing Jinchuan Peatland is now adjacent to the reclaimed peatland, separated by agricultural drainage ditches (Fig. 1e). The eastern region near the drainage ditch has been significantly affected by drainage, with a notable drop in water levels and considerable fluctuations, is classified as the drained area. In contrast, the central area of the peatland, where water levels typically fluctuate slightly near the peatland surface and are currently subject to relatively minor drainage impact, is classified as the transition area. Meanwhile, the western region, maintaining consistently high and stable water levels throughout the year, is classified as the undisturbed natural area (Fig. 1d).

In the Jinchuan Peatland, we established two monitoring sites in each of the undisturbed natural area (S1 and S2), transition area (S3 and S4), and drained area (S5 and S6), totaling six long-term monitoring sites (S1-S6). In each sites, we installed a monitoring well to measure water levels and soil temperature, along with soil collars for GHG measurements (Fig. 1d). Northern peatlands typically exhibit significant seasonal dynamics in GHG emission46. Although some studies have found that the non-growing season plays a role in the year-round methane contribution47, nevertheless, in most cases, the GHG flux during the growing season is still dominant48,49. Previous studies by Kwon et al. (2017) found that drainage reduced CH4 fluxes by a factor of 20 during the growing season, while this impact in the nongrowing season was negligible. This suggests that the effect of drainage on CH4 emissions is primarily observed during the growing season50. Existing studies on GHG emissions from the Jinchuan Peatland also indicate that GHG emissions are more active during the growing season51,52,53. Therefore, we monitored GHG emissions from the Jinchuan Peatland during the growing season, as it scientifically reflects the contribution of GHG emissions on an annual scale. At each of these six sites, we installed automatic monitoring probes to measure water levels and soil temperature, recording data hourly from May to October 2019, as the growing season in this study area spans from early May to October. Correspondingly, GHG fluxes were monitored biweekly from May 14 to October 15, covering the 2019 growing season.

Result

Water table and soil temperature

Throughout the experimental period, a total of 4200 water level and soil temperature measurements were recorded at each monitoring site (S1 ~ S6). The results of Tukey’s HSD test revealed significant differences in both water levels and soil temperatures across all monitoring sites (P < 0.05). The average water levels in the natural area (S1 and S2) were significantly higher, at 11.45 ± 9.16 cm and 10.59 ± 9.27 cm, respectively. In the transition area (S3 and S4), the average water levels were 4.73 ± 10.65 cm and 3.02 ± 7.08 cm, respectively. In the drained area (S5 and S6), the average water levels were − 3.10 ± 8.53 cm and − 13.47 ± 7.84 cm (Table 1). Soil temperatures generally increased from early May, peaked in mid-summer, and then gradually declined until October (Fig. 2). The average soil temperatures in the drained area were 9.06 ± 3.64 °C for S5 and 8.21 ± 4.39 °C for S6, which were lower than the temperatures in the natural and transition areas (S1 ~ S4), which ranged from 10.65 ± 4.83 °C to 12.40 ± 3.11 °C. Drainage not only significantly lowered the water levels in the Jinchuan peatland (from 11.45 cm to -13.47 cm), shifting the area from a prolonged waterlogged state to an unsaturated condition, but it also resulted in a decrease in soil temperature at the depth of 1 m by 1 ~ 3 °C.

Water level and soil temperature of three areas of drainage states. The blue line represent for hourly recorded water level (cm); the red line represent for hourly recorded soil temperature (℃); the vertical yellow dashed lines indicate the timing of GHG sampling campaigns; the blue dashed transverse line indicating the 0 cm water level.

Soil properties

The SOC content in the 0 ~ 40 cm soil layer significantly decreased in the drained area, ranging from 197.31 ~ 374.75 g/kg, compared to 416.40 ~ 459.81 g/kg in the transition area and 437.05 ~ 512.71 g/kg in the natural area. The upper layer SOC in the drained area decreased by 14.25–61.52% compared to the natural area. However, the differences in TN and DOC contents across different drainage state areas were not significant. The pH value in the surface soil (0 ~ 20 cm) was significantly higher in the drained area, ranging from 5.05 ~ 5.29, compared to 4.59 ~ 4.89 in the transition area and 4.64 ~ 4.71 in the natural area. The soil water content (SWC) at the 0–20 cm depth remained relatively high in the natural area, ranging from 531.18 to 540.59%. In the transition area, SWC showed a slight decline, ranging from 417.20 to 539.04%. In contrast, the drained area experienced a significant decrease, with values ranging from 212.73 to 343.27%. The C/N ratio in the 0 ~ 40 cm soil layer was significantly lower in the drained area, ranging from 11.88 ~ 28.48, compared to 30.37 ~ 37.26 in the transition area and 30.26 ~ 32.63 in the natural area (Table 2).

Soil microbial communities

Bacteria

The bacterial phylum composition in the natural and transition areas was relatively similar, however the drainage area showed notable differences (Fig. 3a). In particular, Proteobacteria and Acidobacteriota were more abundant in the drainage area, while Chloroflexi and Bacteroidota were less abundant compared to the natural and transition areas. In the natural and transition areas, Chloroflexi was the dominant phylum, but in the drainage area, the dominance shifted to Proteobacteria. The relative abundance of Chloroflexi declined from 19.2%~23.1% in the natural and transition areas to 10.5%~16.0% in the drainage area, while Proteobacteria increased from 12.0%~15.3–21.6%~39.1%.

Solibacter was dominant aerobic bacteria in the Jinchuan peatland, exhibits a comparable abundance in the natural and transition areas (8.3%~11.9%) but increases significantly in the drained area (14.4%~21.3%). The total abundance of aerobic bacteria demonstrates a progressive increase along the gradient from S1 to S6, rising from 33.2% at S1 to 50.7% at S6 (Fig. 3b). This pattern corresponds to the proximity of the monitoring sites to the drainage ditches, with S1 located the farthest and S6 the closest. Conversely, anaerobic bacteria display an opposite trend, with their total abundance declining from 31.4% at S1 to 11.8% at S6 (Fig. 3c). Among the anaerobic genera, Smithella, BSV26, and Aminicenantales exhibit a marked reduction in abundance within the drained area. Facultatively anaerobic bacteria, which constitute a smaller proportion of the overall bacterial community, are represented by Xanthobacteraceae, Pseudolabrys, and Bradyrhizobium. The abundance of these genera is significantly elevated in the drained area compared to the natural and transition areas (Fig. 3d).

Archaea

The dominant archaea genus in Jinchuan peatland soils are Bathyarchaeia and Methanobacterium. Notably, the relative abundance of Bathyarchaeia increased in the drained areas compared to the natural and transitional zones, ranging from 39.8%~58.2% in the drained areas, versus 39.5%~42.7% in the natural and transitional zones. In contrast, the abundance of Methanobacterium decreases in the transitional and drained zones compared to the natural zones, with relative abundances of 18.8%~21.0% in the transitional and drained zones, compared to 19.2%~36.9% in the natural zones (Fig. 4a).

As for the methanogenic functionality, methanogens in the Jinchuan peatland soils were classified into four types: hydrogenotrophic methanogens, acetoclastic methanogens, methylotrophic methanogens, and multi-substrate methanogens. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens exhibit the highest relative abundance across all drainage conditions but show a marked decline in the drained areas compared to the natural and transitional zones. Their relative abundance ranges from 20.7%~37.9% in the natural zones to 18.1%~23.2% in the transitional and drained zones. Overall, the total relative abundance of methanogens progressively decreases along the gradient from S1 to S6, dropping from 49.1% at S1 to 25.7% at S6 (Fig. 4b). This decline corresponds to the proximity of the sampling sites to drainage ditches, with S1 being the farthest from and S6 the closest to the drainage ditches.

Fungus

Ascomycota and Basidiomycota are the most abundant fungal phyla in the Jinchuan peatland, and they exhibit contrasting responses to drainage (Fig. 5a). Ascomycota is the most dominant in the natural area, accounting for 63.1%~70.9%, but its abundance decreases in the transition area (46.2%~54.6%) and reaches its lowest in the drained area (40.0%~49.8%). In contrast, Basidiomycota has the lowest abundance in the natural area (9.7%~10.3%), but its proportion increases in the transition area (16.5%~27.3%) and peaks in the drained area (27.4%~33.6%). The fungal alpha diversity indices (Ace and Sobs) show a gradual increase from the natural area to the drained area, with higher values in the transition and drained areas (Fig. 5b, c).

The fungal community composition network structures differ significantly across the three drainage states (Fig. 5d and Table S1). In the natural area, the fungal networks at S1 and S2 exhibited the highest modularity (M = 0.58 and M = 0.52, respectively) and a dominance of positive interactions, with positive link percentages of 98.5% at S1 and 90.1% at S2. In the transition area (S3 and S4), the modularity increased to 0.77 and 0.73, respectively, while positive interactions decreased to 80.0% at S3 and 86.3% at S4, indicating a shift towards more negative interactions (20.00% and 13.71%). In the drained area (S5 and S6), the fungal networks displayed high modularity (M = 0.75 and M = 0.69) but further decreases in positive interaction percentages (82.8% at S5 and 80.1% at S6) and increased negative interactions (17.2% and 19.9%). Drainage disrupted fungal community interactions, increased negative interactions and altered network modularity.

Fungal diversity and community composition (a) Relative abundance on Phylum level, (b) Ace index, (c) Sobs index, (d) Networks of three areas of drainage states, nodes of different colors represent different fungal phyla, green edges represent positive interactions between nodes, red edges represent negative interactions.

GHG fluxes

Instantaneous GHG flux

CH4 fluxes exhibit significant spatial and temporal heterogeneity, with higher fluxes observed in July and August and greater fluxes in natural areas compared to drained areas (Fig. S2a). Eco_CH4 fluxes were generally greater than soil_CH4 fluxes, indicating that the plant community in the Jinchuan peatland (Sphagnum + Carex + Phragmites) contributes to increased CH4 emissions. The highest instantaneous CH4 flux was observed in the natural areas, reaching 8.75 ± 2.97 mg·m− 2·h− 1 in July. In the transition areas, CH4 fluxes were relatively lower, with the maximum CH4 flux recorded in August at 4.25 ± 1.11 mg·m− 2·h− 1. In the drained areas, CH4 fluxes were the lowest, with the highest CH4 flux detected in September at 1.53 ± 0.15 mg·m− 2·h− 1. N2O fluxes also exhibit higher fluxes in summer with Eco_N2O fluxes generally exceeding soil_N2O fluxes (Fig. S2b). In natural areas, N2O fluxes were minimal, ranging from − 0.01 ± 0.017 mg·m− 2·h− 1 in October to 0.09 ± 0.034 mg·m− 2·h− 1 in July. In transitional areas, N2O fluxes increased, ranging from − 0.01 ± 0.009 mg·m− 2·h− 1 in October to 0.22 ± 0.058 mg·m− 2·h− 1 in July. In drained areas, N2O fluxes were higher than in both natural and transitional areas, reaching 0.27 ± 0.076 mg·m− 2·h− 1 in July, and remaining relatively low at -0.02 ± 0.019 mg·m− 2·h− 1 in October. CO2 fluxes also exhibited a gradient across different drainage states (Fig. S2c). In natural areas, SR was relatively low, with the highest instantaneous SR flux measured in July at 318.52 ± 65.84 mg·m− 2·h− 1, and NEE was strongly negative during June to August, ranging from − 596.93 ± 101.26 to -896.54 ± 127.02 mg·m− 2·h− 1. In transitional areas, SR flux were higher than the natural areas, with the maximum flux also recorded in July at 657.32 ± 273.72 mg·m− 2·h− 1, and NEE during June to August ranged from − 495.39 ± 67.90 to -870.98 ± 68.13 mg·m− 2·h− 1, reflecting weakened carbon sequestration compared to undisturbed natural areas. In drained areas, the highest SR levels were observed in all three drainage states areas, with the maximum flux reaching 1149.76 ± 310.47 mg·m− 2·h− 1 in July at the S6 site. Meanwhile, the NEE ranged from − 275.94 ± 87.07 to 133.12 ± 41.04 mg·m− 2·h− 1, which was significantly higher than that in the natural and transition areas, or even turned positive, indicating increased carbon emissions and a compromised carbon sequestration capacity in the drained areas.

Interpolated cumulative GHG emission

We processed the instantaneous GHG flux from May to October using linear interpolation to calculate the cumulative emission flux for the entire growing season (May to October). In natural areas, the cumulative soil CH4 emissions were the highest, ranging from 81.49 ± 4.32 to 113.03 ± 5.08 kg·CH4·ha− 1·season− 1, which was 3.26 to 7.36 times higher than in drained areas, while CO2 and N2O emissions were the lowest, at approximately 5.63 ± 0.47 ~ 8.27 ± 0.57·t CO2·ha− 1·season− 1 and 0.23 ± 0.03 ~ 0.38 ± 0.01 kg·N2O·ha− 1·season− 1, respectively (Fig. 6a, b,c). With the degree of drainage increases, soil CO2 and N2O emissions rose significantly, reaching 11.29 ± 1.53 ~ 12.56 ± 0.74 t·CO2·ha− 1·season− 1 and 0.78 ± 0.21 ~ 0.81 ± 0.18 kg·N2O·ha− 1·season− 1 in transitional areas and further increasing to 21.31 ± 1.93 ~ 23.16 ± 0.57 t·CO2·ha− 1·season− 1 and 1.51 ± 0.27 ~ 1.98 ± 0.36 kg·N2O·ha− 1·season− 1 in drained areas.Meanwhile, on the contrary, CH4 emissions gradually decreased with drainage, dropping to 59.65 ± 5.63 ~ 61.96 ± 4.10 kg·CH4·ha− 1·season− 1 in transitional areas and further down to 15.35 ± 1.67 ~ 24.97 ± 1.58 kg·CH4·ha− 1·season− 1 in drained areas. In terms of the net GHG emissions in CO2 equivalent, natural areas had the lowest emissions (approximately 8.86 ± 0.44 ~ 10.65 ± 0.56 t·CO2-eq·ha⁻¹·season⁻¹), transitional areas exhibited moderate emissions (about 13.18 ± 1.48 ~ 14.50 ± 0.79 t·CO2-eq·ha⁻¹·season⁻¹), and drained areas recorded the highest emissions (22.27 ± 2.02 ~ 24.26 ± 0.56 t·CO2-eq·ha⁻¹·season⁻¹) which was 2.09 ~ 2.74 times higher than in natural areas. Overall, drainage significantly reduced CH4 emissions but increased CO2 and N2O emissions, ultimately leading to a notable increase in net GHG emissions primarily driven by the substantial increase in CO2 emissions (Fig. 6d).

Cumulative GHG fluxes of three areas of drainage states, (a) Soil_CO2 flux, (b) Soil_CH4 flux, (c) Soil_N2O flux, and (d) Net GHG emission in carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-eq). Data are presented mean value ± SE, n = 3. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among monitoring sites (P < 0.05).

Relationship between soil environmental factors and GHG fluxes

Soil respiration and soil N2O fluxes are negatively correlated with the water table (Fig. 7a, e), while soil CH4 flux is positively correlated with the water table (Fig. 7c). Soil temperature is another critical factor, positively correlated with soil respiration (Fig. 7b) and CH4 fluxes (Fig. 7d). In addition to water level and soil temperature, soil pH is also a significant influencing factor. Soil pH is strongly linked to CO2, CH4 fluxes, and net GHG emissions (Fig. S3). SR is positively correlated with the abundance of aerobic bacteria and facultatively anaerobic bacteria, as well as soil pH, while it is negatively correlated with the abundance of anaerobic bacteria, soil moisture content, and soil C/N (Fig. S3a). CH4 emission flux is positively correlated with methanogens (mainly hydrogenotrophic methanogens) and water level, while it is negatively correlated with soil pH (Fig. S3b). Net GHG emissions in CO2 equivalent are positively correlated with the abundance of aerobic bacteria and facultatively anaerobic bacteria, as well as soil pH, while they are negatively correlated with water level, abundance of anaerobic bacteria, and abundance of methanogens (Fig. S3c).

The results of the multiple regression model show that the changes in environmental factors caused by peatland drainage have a significant interactive effect on GHG emissions (Table 3). The combination of soil temperature and inundation status significantly improves the predictive power of the SR and CH4 flux models (R2 values increase from 0.34 to 0.38 for SR and from 0.34 to 0.37 for CH4 flux when inundation status is included). Furthermore, drainage effects are more pronounced near drainage ditches, as shown in both the SR and CH4 flux models. The inclusion of ‘Proximity to the drainage ditch’ (Prox to DD, categorized as proximal or distal by dummy variable transformation) in Model 3 further improved R² values (e.g., 0.52 for SR and 0.43 for CH4 flux), indicating the localized impact of drainage. Seasonal variations also play a role, with higher emissions during warmer seasons, and as indicated in Table 3, where the inclusion of season improves model performance (R² increases from 0.52 to 0.55 for SR). The results of the multiple regression model highlight the complex and localized effects of drainage on peatland GHG fluxes, with seasonality and proximity to drainage ditches playing significant roles in the spatial and temporal variability of emissions.

Further structural equation modeling analysis results show that, for soil respiration and CH4 emissions, although water level and inundation status have significant effects, soil temperature exhibits the strongest direct effect, and season is the main factor regulating soil temperature (Fig. 8). This implies that if global climate change leads to seasonal temperature variations in northern regions, which in turn affect soil temperature in northern peatlands, it could ultimately have a significant impact on GHG emissions from peatlands. In addition, the structural equation modeling results show that proximity to drainage ditches has a significant direct effect on SR (0.60**, Fig. 8a). In comparison, CH4 emissions are primarily controlled by soil temperature, inundation status, and season, while proximity to drainage ditches indirectly affects CH4 emissions by influencing soil temperature and inundation status (Fig. 8b).

Structural equation modeling analysis of environmental factors on (a) SR and (b) soil_CH4 flux. ** indicates very significant (P < 0.001), * indicates significant (P < 0.005), dashed lines indicate P > 0.005. Blue lines represent significant negative impacts. Red lines represent significant positive impacts. The pathways indicate the direction and strength of these relationships.

Discussion

Drainage significantly altered the peatland soil environment, primarily by lowering the water table, which shifted the peatland from a saturated to an unsaturated state. This reduction in water level further led to changes in the soil’s redox environment, enhancing aerobic microbial activity. As a result, soil pH increased, SOC content decreased, and the soil C/N ratio lowered. Our study found drainage enhancing aerobic microbial activity, particularly Solibacter. Mastny et al. (2021) identified Solibacter (Acidobacteria) as one of the key bacterial taxa with the potential to decompose complex organic carbon in peatlands54. Our study found that the SOC content in the 0 ~ 40 cm soil layer was significantly lower in the drained areas compared to the natural areas, along with a reduced C/N ratio. This result is consistent with the findings of Leifeld et al., (2020), who observed that drainage in peatlands for agriculture lead to significant losses of organic matter and a decrease in the C/N ratio55. Additionally, the study by Chen et al. (2024) investigated the effects of drainage on the soil physicochemical properties and organic carbon fractions of the Baijianghe peatland in Northeast China. They found that drainage resulted in a total soil carbon loss of 25%, and they found that over 80% of the total carbon loss after drainage was attributed to the loss of recalcitrant carbon fractions56. Based on our experimental results and those of previous studies, it can be inferred that drainage leads to an increase in Solibacter in the soil, which enhances the soil microbial community’s ability to decompose complex organic carbon, thereby resulting in a decrease in soil SOC and C/N ratio in drained peatlands.

Our study found that drainage significantly increased soil pH in the surface layer, with pH values in the drained areas ranging from 5.05 to 5.29, which were significantly higher than those in the natural (4.64 ~ 4.71) and transition areas (4.59 ~ 4.89). Zhang et al., (2024), who also observed that long-term drainage and afforestation in peatland soils on the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau in China led to significant changes in soil physicochemical properties, including an increase in pH. They also pointed out that pH is one of the key driving factors for changes in soil bacterial community composition and diversity57. In contrast, Urbanova et al. (2016) observed that drainage caused a decrease in pH, and also resulted in reduced microbial activity. Similarly, Toberman et al. (2010) reported that drainage led to soil acidification and suppressed phenol oxidase activity58,59. These findings contrast with the increase in pH observed in the drained areas in our study. The possible reason for this discrepancy is that in our study, the drained soils were exposed to higher oxygen concentrations, which, as evidenced by the significantly increased abundance of aerobic bacteria in the drained areas, likely promoted aerobic microbial decomposition and increased soil pH. In contrast, Urbanova et al. (2016) and Toberman et al. (2010) found that drainage suppressed microbial activity, which could be attributed to differences in peatland type, drainage history, and the intensity of drainage in their studies.

Our results indicated, the increase in aerobic bacterial populations played a key role in driving CO2 emissions. Specifically, microbial communities in drained areas showed significant shifts, including a decrease in the relative abundance of Desulfobacteriota and an increase in Proteobacteria and Acidobacteriota. These microbial community changes likely contributed to the altered CO2 emissions observed in drained peatlands. Munford et al. (2023) observed a shift in bacterial and archaeal community composition as the distance from the stressor increased. Specifically, they noted a decrease in the proportion of Acidobacteria, particularly the order Acidobacteriales, which suggests that Acidobacteria especially the order Acidobacteriales, are associated with environmental stress60. As environmental stress increases, the abundance of Acidobacteria decreases. In contrast, our study found an increase in Acidobacteriota, particularly Solibacter, in the drained areas, indicating that drainage reduced environmental stress on aerobic bacteria, leading to an increase in their abundance.Furthermore, our results showed that facultatively anaerobic bacteria, which make up a smaller proportion of the overall bacterial community, are represented by genera such as Xanthobacteraceae, Pseudolabrys, and Bradyrhizobium. The abundance of these genera was significantly higher in the drained areas compared to the natural and transition zones. Recent research has highlighted that Xanthobacteraceae could play an important role in microbial community composition, particularly under conditions where different carbon sources are utilized61. This may suggest that the types of carbon sources in the drained areas are more diverse compared to natural areas. In drained zones, where water tables are lowered and oxygen availability increases, the microbial community may undergo a selection process favoring facultatively anaerobic bacteria that can thrive in such conditions. This, in turn, might indicate that the carbon sources available in the drained areas are more diverse and varied compared to natural areas, where anaerobic conditions tend to dominate. Facultatively anaerobic bacteria, such as those from Xanthobacteraceae, are known to utilize a variety of organic substrates, including complex compounds such as lignocellulose, which are abundant in peatlands. Additionally, studies by Kunarso et al. (2024) and Wang et al. (2023) have found that drainage not only reduces SOC but also alters the molecular composition of SOC62,63, which supported this standpoint.

In addition to bacteria, fungal community structure also shows a significant response and role in the drainage process of peatlands. Our study found that drainage significantly affected the fungal community composition in the Jinchuan peatland, with Ascomycota and Basidiomycota showing contrasting responses to drainage. Specifically, Ascomycota had the highest relative abundance in the natural area (63.1%~70.9%) but declined in the drained area (40.0%~49.8%), whereas Basidiomycota had the lowest relative abundance in the natural area (9.7%~10.3%) but increased in the drained area (27.4%~33.6%). Peltoniemi et al., (2009) also identified Ascomycota and Basidiomycota as the predominant fungal phyla in a boreal peatland in Finlan, and reported that Basidiomycota responds more significantly to hydrological changes than Ascomycota64. Additionally, our study observed an increasing trend in fungal alpha diversity indices (Ace and Sobs) across the drainage gradient, which is in agreement with the findings of Ali et al., (2018). They found that Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were the dominant fungal phyla across various peatland ecosystems and that fungal diversity increased following drainage65. Regarding fungal network structure, we found that fungal networks in the drained areas exhibited high modularity, with an increase in negative interactions and a decrease in positive interactions. Runnel et al., (2023) observed that in drained peatland forests in Estonia, water level restoration and natural conditions increased the relative abundance of saprotrophic fungi26. This results from our study and previous research together indicate that drainage not only alters the relative abundance of fungal phyla (mainly Ascomycota and Basidiomycota) in peatlands, but also impacts community interactions and diversity, which could have broader implications for carbon storage capacity and GHG emissions in peatland ecosystems. There are studies indicate that in most peatlands, bacteria contribute more to CO2 production than fungi66, and prokaryotes are the primary factor influencing greenhouse gas emissions from drained peatlands67. However, fungi play a crucial role in the carbon sequestration potential of northern peatlands, particularly in the decomposition of recalcitrant compounds such as cellulose and lignin. For instance, a study on intact peatland ecosystems in Canada found that climate warming and water table fluctuations led to structural changes in fungal communities, dominated by Ascomycota and Basidiomycota68.These changes favor decomposers of recalcitrant compounds, which in turn promote CO2 emissions.

CH4 emissions from the Jinchuan peatland decreased significantly after drainage, from 81.49 ± 4.32 ~ 113.03 ± 5.08 kg·CH4·ha− 1·season− 1 in the natural areas, to 15.35 ± 1.67 ~ 24.97 ± 1.58 kg·CH4·ha− 1·season− 1 in the drained areas. This is consistent with previous studies, such as Ingle et al. (2023), who found that methane fluxes in natural areas were much higher than in drained areas. They observed CH4 fluxes of 2.25 and 3.80 g C·m− 2·year− 1 in natural areas, compared to 0.15 and 0.27 g C·m− 2·year− 1 in drained sites, indicating that methane emissions in natural areas were 8.3 to 25.3 times higher than in drained areas69. In our study, high water tables and anaerobic conditions in natural area promoted methanogenic activity, particularly hydrogenotrophic methanogens, which produced methane. In contract, in drained area as the soil environment shifted to a more aerobic state, the abundance of methanogenic archaea, especially Methanobacterium, decreased significantly. This decrease in methanogenic activity, reflected in the lower abundance of hydrogenotrophic methanogens, further supports the reduced methane emissions observed in the drained areas. Studies by Wang et al. (2024) on the soils of northern peatlands in Northeast China similarly indicated that Bathyarchaeia and Acidobacteriota play crucial roles in organic carbon and nitrogen cycling in peat soils. In terms of methane turnover, various methanogenic pathways—acetoclastic, hydrogenotrophic, and methylotrophic—are all likely involved in methane production70. Our results align with these findings, confirming that Bathyarchaeia are significantly impacted by drainage. Prasitwuttisak et al. (2022) also noted that Bathyarchaeia, with its extensive metabolic capabilities, is abundant in anoxic environments, particularly in subsurface peat soils, where it can constitute up to 96% of the archaeal community71. In addition, Wang et al. (2017) observed that the reduction in methane emissions was primarily attributed to a decrease in methane production potential, rather than an increase in methane oxidation72. Kwon et al. (2017) also found that drainage significantly reduced the abundance of methanogens, which may have led to a reduction in CH4 cycling50. Their study suggests that the decline in methanogenic communities due to drainage was the main reason for the reduced methane emissions. Further, Kwon et al. (2021) studied the microbial communities in Arctic floodplain soils after ten years of drainage, reporting an increase in fungal abundances and a substantial reduction in methane emissions. They observed that key methanogens, such as Methanoregula, almost disappeared in the drained sites73. Keuschnig et al. (2022) found a similar decrease in methane emissions in Arctic peatlands, where 15 to 25 years of natural drainage led to a tenfold reduction in methane emissions, partly due to a loss of methanogens and increased methane oxidation in drier, aerated soils74. Studies on rewetting, such as by Weil et al. (2020) and Ma et al. (2011), have shown that rewetting sites exhibit higher abundances of anaerobic taxa compared to drained sites, with methanogens being more than ten times more abundant in rewetted sites75,76. This highlights the important role of soil moisture in shaping microbial communities and methane production. Based on our findings and previous studies, it can be concluded that, drainage significantly reduces methane emissions by decreasing the abundance of methanogenic archaea in peatlands. This substantial reduction in methane fluxes is consistent with findings from various studies on both temperate and Arctic peatlands.

In addition to the damage caused by water stress and oxygen during drainage, which significantly reduces the abundance of methanogens, the increased soil pH in drained areas is also a crucial factor in altering the composition of methanogenic communities and influencing methane emissions in peatlands. Our results show that the soil pH in the surface layers of drained areas was negatively correlated with CH4 flux, further supporting the idea that the increase in soil pH and the reduction in methanogen abundance are key factors in the suppression of CH4 emissions. Previous studies have shown that hydrogenotrophic methanogens are more acid-tolerant than acetoclastic methanogens77,78. Gorres et al. (2013) also found that the composition of archaeal communities was strongly linked to soil pH. At a fen site, where the soil pH ranged from 3.2 to 4.4, no methanogens were detected. In contrast, the methanogenic community in a bog (with a soil pH of 3.9 to 4.6) was dominated by hydrogenotrophs, while the second fen site (with a soil pH ranging from 5.0 to 5.3) contained both acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogens79. In addition to methanogens and soil pH, soil temperature may also important factors affecting CH4 emissions in drained peatlands. Our results show that soil temperature in the drained areas was lower compared to the natural areas (by 1 ~ 3 °C). Kwon et al. (2017) also found that soil temperatures in the drained areas were lower in deeper, anoxic soil layers (below 30 cm) but higher in the oxic topsoil layers (0 ~ 15 cm) compared to the control wet areas50. In our experiment, the temperature probes were placed 1 m below the surface of the peatland, which confirmed the reduced soil temperature in the deeper layers of drained peatlands. Although we were unable to monitor the temperature changes in the upper layers, the study by Kwon et al. (2017) indicated that drainage increased soil temperatures in the oxic surface layers, which may contributed to the increase of soil CO2 and decrease of CH4 emissions in our study. This pattern of soil temperature distribution may have reduced methanogenesis rates while enhancing CH4 oxidation, thereby lowering net CH4 fluxes.

As for the impact of drainage on N2O emissions from peatlands, our study shows that drainage significantly increased N2O emissions, especially during the summer. Specifically, N2O emissions in the drained areas reached 0.27 ± 0.076 mg·m2·h− 1 in July, significantly higher than those in natural and transitional areas. This finding is consistent with previous research. For example, Lin et al. (2022) found that drainage stimulated N2O emissions in natural minerotrophic wetlands, while rewetting reduced N2O emissions in drained minerotrophic wetlands. They suggested that N2O emissions were driven by a simultaneous decline in groundwater levels and an increase in soil nitrogen availability80. Swails et al. (2024) also observed an increase in N2O emissions in drained peat swamp forests in Southeast Asia81, which is consistent with our results. Berendt and Wrage-Moennig (2023) found that drainage increased N2O fluxes in peatlands in northeastern Germany, with denitrification accounting for 80-90% of N2O production82. This finding aligns with our study, where we hypothesize that enhanced aerobic microbial activity in drained areas is the primary driver for increased N2O emissions. However, there are still some studies whose results differ from ours. For instance, Gudmundsson et al. (2024) suggested that lower drainage levels and nutrient availability could reduce N2O emissions. They proposed that the stable moisture content and limited soil phosphorus availability after drainage might hinder N2O production while promoting N2O consumption83. This contrasts with our findings, where drainage consistently increased N2O emissions. The difference may be due to variations in peatland types, water table fluctuations, or nutrient conditions. For instance, the specific moisture and nutrient conditions in Gudmundsson et al.‘s study might have favored N2O consumption, while in our study, the drainage conditions were more conducive to N2O production. In conclusion, our study confirms that drainage leads to an increase in N2O emissions from peatlands, with emissions in drained areas significantly higher than in natural and transitional areas. However, our research differs from previous studies in terms of emission levels and driving mechanisms. While denitrification is a common driver of N2O emissions, our study highlights the potential role of seasonal variation in N2O fluxes in drained areas. The differences between studies suggest that the effect of drainage on N2O emissions in peatlands is complex, influenced by a combination of hydrological conditions, soil properties and microbial processes.

From the perspective of spatial heterogeneity in greenhouse gas emissions, our results highlights the significant role of proximity to drainage ditches. We found that the effects of drainage were more pronounced near drainage ditches, particularly in terms of CO2 emissions. Silins (1997) reported that oxygen transport rates and oxygen concentrations were consistently higher in drained areas compared to undrained areas, with the aerated zone extending 10 to 40 cm deeper84. Specifically, the proximity to drainage ditch edges influenced both oxygen transport rates and the depth of the aerated zone, which aligns with our results indicating that proximity to drainage ditches intensifies drainage effects in localized areas. Additionally, Zhang et al. (2019) studied a degraded alpine fen on the Tibetan Plateau and found that CH4 emissions ranged from 0.2 to 63.3 kg C ha⁻¹ yr⁻¹, with a significant correlation to the distance from the drainage ditch across micro-sites47. This supports our observation that proximity to drainage ditches affects CH4 emissions. Drainage typically leads to lower water tables, which deepens the oxygenated zone in the soil and accelerates the oxidation of organic carbon, thereby increasing CO2 emissions. For CH4 emissions, drainage alters both soil pH and waterlogging conditions, which in turn affect methanogenesis and methane oxidation processes. The closer the proximity to drainage ditches, the more pronounced this effect likely becomes. These findings underscore the importance of spatial variability in drainage effects and their influence on GHG fluxes in peatland ecosystems.

Last but not least, our study acknowledges certain limitations. Due to experimental constraints, we were unable to include an analysis of changes in plant community structure, which could potentially influence greenhouse gas emissions. A substantial number of literature indicates that water level alteration in peatlands significantly affect changes in plant community structure, which may, in turn, influence greenhouse gas emissions. Water level changes after drainage not only directly impact soil moisture, redox conditions, and microbial communities, thereby affecting soil carbon and nitrogen cycles, but also significantly alter plant community composition85,86. For example, Y.-H. Yang et al. (2020) studied the Baijianghe peatland in the Changbai Mountains and found that drainage not only alters the environmental and ecological processes of peatlands but also significantly impacts plant community structure, particularly the spore germinability of mosses87. Wang et al. (2024) conducted a study on a minerotrophic peatland in northern China and pointed out that the decrease in water level due to drainage exacerbates phosphorus limitation for both plants and microorganisms in peatlands88. Additionally, different combinations of water levels and plant communities have a significant impact on soil carbon components89, which may further alter greenhouse gas emissions. For instance, although sustained high water levels can reduce carbon dioxide emissions, Feng et al. (2017) found that continuous waterlogging may not be favorable for maintaining high germinability of Sphagnum spores90. While our study did not examine the response of plant communities in drained peatlands and their subsequent impact on greenhouse gas emissions, the alterations in plant community structure represent a significant influencing factor, as evidenced by existing literature. Consequently, future studies should integrate these changes to further elucidate their role in greenhouse gas flux dynamics.

Methods

Water table and soil temperature monitoring

CTD-Diver groundwater automatic measuring instruments (Eijkelkamp Ltd., Netherlands) were installed in the soil for continuous, real-time monitoring of the water table and soil temperature. The instruments recorded data at hourly intervals from May 1 to October 31, 2019. A perforated PVC pipe was installed in the peat soil to serve as a water table observation well, facilitating interaction between the interior of the pipe and the surrounding soil. Inside the pipe, a CTD-Diver sensor was placed 1 m below the ground surface to ensure it remained fully submerged in water (Fig. S4a and S4b). Additionally, a Baro-Diver pressure compensator was placed in a nearby safe, open-air location. The water table was determined by analyzing pressure readings from the CTD-Diver in combination with the barometer. Soil temperature was directly measured and automatically recorded every hour by the CTD-Diver sensor.

Measurements of soil properties

The sampling of soil properties were conducted on July 16, 2019. A soil sampler was used to collect soil cores from depths of 0 ~ 60 cm, dividing them into three layers: 0 ~ 20 cm, 20 ~ 40 cm, and 40 ~ 60 cm. At each research site, three random plots were selected for replication. In each plot, the five-point sampling method was applied to minimize random error (Fig. S5). SOC were determined by dichromate oxidation and titration with ferrous ammonium sulfate91. Soil total nitrogen (TN) was analyzed by the Kjeldahl method. Soil water content (SWC) was measured by weighing fresh and corresponding dry soil samples (70 ℃ for 72 h). Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was measured by water extraction at a soil/water ratio of 1:10 (m/V) and analyzed by a total organic carbon analyzer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). Soil pH was measured using a 1:5 solid-water suspension and detected with a pH meter (METTLER).

Soil microbial sampling and DNA sequencing

Soil microbial sampling was carried out on July 16, 2019. Samples from the 0 ~ 30 cm depth were collected using the five-point sampling method. Within each treatment group, three random sampling points were selected to serve as replicates.After sample collection, they are placed into sterile sampling tubes and stored in a dry ice cooler for transportation to the laboratory. Upon arrival, they are stored at -80 °C. Extracted DNA was detected by the 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, PCR amplification was carried out using a PCR Amplifier (ABI GeneAmp®, 9700 ). The gene primer pair used for bacterial, fungal and archaeal diversity sequencing are 338F_806R (468 bp), ITS1F_ITS2R (300 bp) and 524F110extF_Arch958RmodR (434 bp) respectively. Gene sequencing was performed on the Nextera XT kit (Illumina) on an Illumina MiSeq at Majorbio Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The classification of bacteria and archaea is based on the Silva database (Release 138, http://www.arb-silva.de), and the classification of fungi is based on the Unite fungal database (Release 8.0, http://unite.ut.ee/index.php).

GHG flux measurement

Instantaneous GHG flux

For ecosystem GHG flux measurements, we used modular, height-adjustable transparent chambers to measure instantaneous NEE, Eco_CH4 flux, and Eco_N2O flux, ensuring that the plants remained intact within the chambers. For soil GHG flux measurements, we used opaque chambers to measure instantaneous soil respiration, Soil_CH4 flux, and Soil_N2O flux, with the above-ground vegetation removed. The transparent chamber is composed of three parts: the top box, middle box (height adjust module) and the base. The sampling box of the transparent chamber is made of high light transmittance plexiglass material (Fig. S4d). The specification of the top box is 50 × 50 × 50 cm, and the middle section (height extension box) is 50 × 50 × 100 cm. The opaque chamber is constructed from a transparent chamber modified with shading treatment (Fig. S4c). The base is made of PVC material, with dimensions of 50 cm × 50 cm × 30 cm. Holes are drilled at the bottom to allow plant roots to maintain contact with the surrounding soil, minimizing the base’s impact on the soil environment. Additionally, there is a groove on the top for water injection during sampling to ensure a proper seal. The bases were placed on May 7, 2019, and inserted 15 cm into the soil. At the soil GHG monitoring sites, surface vegetation was clipped. Throughout the growing season, any newly grown vegetation within the bases was removed a few days before the GHG sampling campaign. Sampling was conducted on clear days between 10:00 and 13:00, represents the daily average of GHG fluxes92,93. The static chambers are equipped with small fans on the top, which is used to rotate and stir the gas in the box during the gas collecting. During the growing season, as the height of Phragmites australis typically exceeds 60 cm, a middle box (height adjustment module) is required. The top chamber is then inserted into the groove, and water is added to the groove to ensure a proper seal. A sampling pump is connected to the sampling port on the top chamber to collect gas samples. Sampling is conducted at 10-minute intervals, with four samples taken at 0 min, 10 min, 20 min, and 30 min, respectively, while simultaneously recording the temperature inside the chamber. After collecting the gas into an aluminum foil sampling bag (500 mL, Dalian Delin Gas Packaging Co., Ltd.), promptly take it back to the laboratory for analysis and testing.

GHG concentrations were analyzed using a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890, Santa Clara, California, USA, Fig. S4e). CO2 and CH4 concentrations were determined with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID), while N2O concentration was determined using an Electron Capture Detector (ECD). N2 was employed as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 45 mL min⁻¹. For the ECD, a mixture of argon and methane (Ar-CH4, 95%/5%) was used as the make-up gas at a flow rate of 40 mL min⁻¹. The FID operated with a supply of 45 mL min⁻¹ H2, 450 mL min⁻¹ air, and 20 mL min⁻¹ N2. The injection port, column, ECD, and FID temperatures were set at 80 °C, 80 °C, 325 °C, and 200 °C, respectively. The GHG emission fluxes were calculated as the following Eq. 47:

Among them, F is the GHG flux (mg·m-2 h-1); ρ is the GHG density in the standard state (mg·m-3); h is the height from the airtight tank to the water surface (m); dc/dt is the GHG change rate of the concentration; T is the temperature in the chamber during the sampling process (°C).

Interpolation of cumulative GHG emission

Cumulative soil GHG emissions were calculated from the daily instantaneous GHG flux between every two consecutive measurements using linear interpolation, assuming the existence of linear changes in soil GHG emissions between two successive sampling dates94,95. The formula for calculating seasonal cumulative soil GHG emissions is as follows96,97:

where, Ri is the mean gas flux (mg m-2 d− 1) of the two sampling times, Di is the number of days in the sampling interval, and n is the number of sampling times. Interpolated daily gas fluxes were summed up to calculate the emissions for total growing seasonal emissions.

The net GHG emissions in carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-eq) was estimated using the radiative forcing potentials relative to CO2, i.e. 298 and 25 for N2O and CH4, respectively98. The net GHG emissions was calculated using the following equation:

MCO2, MCH4, and MN2O are the cumulative emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide respectively, and 25 and 298 are the multiples of the GWP values of methane and nitrous oxide relative to carbon dioxide respectively99.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of Variance with Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05) was employed to evaluate differences in soil properties and cumulative GHG fluxes across sites S1 to S6. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to investigate the relationships between water table levels, soil temperature, and GHG fluxes. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to examine the impact of water table levels, soil temperature, season (spring, summer or autumn), proximity to drainage ditch (proximal or distal), and inundation status (categorized from hourly water level data into continuous inundation, intermittent inundation and continuous non-inundation) on GHG emissions. Among all significant models, the one with the lowest root mean squared error was considered to represent the most direct explanatory variables for GHG fluxes. The above statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0. Principal component analysis was performed using the “stats” and “factoextra” packages in R to explore the influence of water table levels, soil temperature, soil properties, bacterial aerobicity and methanogen types on GHG emissions. Structural equation modeling was conducted using the “lavaan” package in R to elucidate the pathways and weights of the effects of water table levels, soil temperature, season, proximity to drainage ditches and inundation status on GHG emissions. The classification of bacterial aerobic/anaerobic functional groups was performed using BugBase (https://bugbase.cs.umn.edu/index.html). OTUs were first normalized based on predicted 16 S copy numbers, and then microbial phenotypes were predicted using the pre-calculated files provided. The classification of methanogenic functional groups was conducted using the FAPROTAX (1.2.1) database, which maps prokaryotic taxa to metabolic or other ecologically relevant functions. The OTU table of the samples was converted into a functional OTU table related to methanogenic functions. The fungal network analysis were performed using R (igraph and vegan) and Gephi.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The raw sequencing reads for this study were submitted to the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under under the accession number PRJNA1204167.

References

Limpens, J. et al. Peatlands and the carbon cycle: from local processes to global implications - a synthesis. Biogeosciences 5, 1475–1491. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-5-1475-2008 (2008).

Rezanezhad, F. et al. Structure of peat soils and implications for water storage, flow and solute transport: A review update for geochemists. Chem. Geol. 429, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.03.010 (2016).

Limpens, J., Heijmans, M. M. P. D. & Berendse, F. The Nitrogen Cycle in Boreal Peatlands. (Springer, 2006).

Yu, Z., Loisel, J., Brosseau, D. P., Beilman, D. W. & Hunt, S. J. Global peatland dynamics since the last glacial maximum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010gl043584 (2010).

Leifeld, J. & Menichetti, L. The underappreciated potential of peatlands in global climate change mitigation strategies. Nat. Commun. 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03406-6 (2018).

Guenther, A. et al. Prompt rewetting of drained peatlands reduces climate warming despite methane emissions. Nat. Commun. 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15499-z (2020).

Olefeldt, D. et al. A decade of boreal rich Fen greenhouse gas fluxes in response to natural and experimental water table variability. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 2428–2440. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13612 (2017).

Wang, Y., Calanca, P. & Leifeld, J. Sources of nitrous oxide emissions from agriculturally managed peatlands. Glob. Change Biol. 30. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17144 (2024).

Joosten, H., Tapio-Bistrom, M. L. & Tol, S. Peatlands – guidance for climate changes mitigation through conservation, rehabilitation and sustainable use. (2012).

Tiemeyer, B. et al. High emissions of greenhouse gases from grasslands on peat and other organic soils. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 4134–4149. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13303 (2016).

Salimi, S., Berggren, M. & Scholz, M. Response of the peatland carbon dioxide sink function to future climate change scenarios and water level management. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5154–5168. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15753 (2021).

Yang, T. et al. Impact of water table on methane emission dynamics in terrestrial wetlands and implications on strategies for wetland management and restoration. Wetlands 42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-022-01634-7 (2022).

Wang, H., Ho, M., Flanagan, N. & Richardson, C. J. The effects of hydrological management on methane emissions from southeastern shrub bogs of the USA. Wetlands 41, 87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-021-01486-7 (2021).

Mwagona, P. C., Yao, Y., Yuanqi, S. & Yu, H. Effect of water level fluctuation and nitrate concentration on soil-surface CO2 and CH4 emissions from riparian freshwater marsh wetland. Wetlands 41, 109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-021-01501-x (2021).

Luta, W. et al. Water table fluctuation and methane emission in pineapples (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.) cultivated on a tropical peatland. Agronomy 11, 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11081448 (2021).

Zhao, M. et al. Responses of soil CO2 and CH4 emissions to changing water table level in a coastal wetland. J. Clean. Prod. 269, 122316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122316 (2020).

Yvon-Durocher, G. et al. Methane fluxes show consistent temperature dependence across microbial to ecosystem scales. Nature 507, 488–491. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13164 (2014).

Inglett, K. S., Inglett, P. W., Reddy, K. R. & Osborne, T. Z. Temperature sensitivity of greenhouse gas production in wetland soils of different vegetation. Biogeochemistry 108, 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-011-9573-3 (2012).

Zhu, D. et al. Methane emissions respond to soil temperature in convergent patterns but divergent sensitivities across wetlands along altitude. Global Change Biol. 27, 941–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15454 (2021).

Cui, M. et al. Warmer temperature accelerates methane emissions from the Zoige wetland on the Tibetan plateau without changing methanogenic community composition. Sci. Rep. 5, 11616. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11616 (2015).

Bansal, S., Tangen, B. & Finocchiaro, R. Temperature and hydrology affect methane emissions from prairie pothole wetlands. Wetlands 36, 371–S381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-016-0826-8 (2016).

Yi, B. et al. The Effect of Warming-Amplified Phosphorus Addition on a Peatland’s N < sub > 2 O Emissions. Agronomy-Basel 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13122947 (2023).

Chen, H., Xu, X., Fang, C., Li, B. & Nie, M. Differences in the temperature dependence of wetland CO2 and CH4 emissions vary with water table depth. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 766–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01108-4 (2021).

Grant, R. F. Ecosystem CO2 and CH4 exchange in a mixed tundra and a Fen within a hydrologically diverse Arctic landscape: 2. Modeled impacts of climate change. J. Geophys. Research-Biogeosciences 120, 1388–1406. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jg002889 (2015).

Heathwaite, A. L.Solute transfer from drained Fen peat. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 55, 379–395 (1991).

Runnel, K. et al. Short-term responses of the soil Microbiome and its environment indicate an uncertain future of restored peatland forests. J. Environ. Manage. 345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118879 (2023).

Nijman, T. P. A. et al. Drainage effects on carbon budgets of degraded peatlands in the North of the Netherlands. Sci. Total Environ. 935 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172882 (2024).

Esterle, J. S. & Ferm, J. C. Spatial variability in modern tropical peat deposits from Sarawak, Malaysia and Sumatra, Indonesia: analogues for coal. Int. J. Coal Geol. 26, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-5162(94)90030-2 (1994).

Couwenberg, J., Dommain, R. & Joosten, H. Greenhouse gas fluxes from tropical peatlands in south-east Asia. Global Change Biol. 16, 1715–1732. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02016.x (2009).

Yule, C. M. & Gomez, L. N. Leaf litter decomposition in a tropical peat swamp forest in Peninsular Malaysia. Wetlands Ecol. Manage. 17, 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-008-9103-9 (2009).

Yi, B. et al. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus additions on nitrous oxide fluxes in a peatland in NE China. Plant. Soil. 502, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-024-06569-y (2024).

Yi, B., Lu, F. & Bu, Z. J. Nitrogen addition turns a temperate peatland from a near-zero source into a strong sink of nitrous oxide. Plant. Soil. Environ. 68, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.17221/411/2021-pse (2022).

Tan, Y. et al. Long-term artificial drainage altered the product stoichiometry of denitrification in alpine peatland soil of Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Geoderma 428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.116206 (2022).

Ma, X. et al. Carbon Reserves and Emissions of Peatlands in China. (Chinese Forestry, 2013).

Wang, C. Q. A dynamic research on carbon storge and carbon budget in peatlands in China. (2009).

Liu, X., Jin, S. & Lu, X. Wetlands in Northeastern China. Wetland Type Distribution Sci. Press. Beijing, 8–10 (2005).

Li, Y. Present situation, protection and management countermeasures of peat resources in Jilin Province. Wetl Sci. 11, 404–406 (2013).

Wang, G., Wang, M., Lu, X. & Jiang, M. Effects of farming on the soil seed banks and wetland restoration potential in Sanjiang plain, Northeastern China. Ecol. Eng. 77, 265–274 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Effect of paddy cultivation on nematode community in Jinchuan wetland of Changbai mountain area, China. Ecol. Eng. 96, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.12.042 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Towards multi-level biomonitoring of nematodes to assess risk of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution in Jinchuan wetland of Northeast China. Ecotoxicology 24, 2190–2199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-015-1550-5 (2015).

Bao, K., Yu, X., Jia, L. & Wang, G. Recent carbon accumulation in Changbai mountain peatlands, Northeast China. Mt. Res. Dev. 30, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd-journal-d-09-00054.1 (2010).

Wang, X., Siciliano, S., Helgason, B. & Bedard-Haughn, A. Responses of a mountain peatland to increasing temperature: A microcosm study of greenhouse gas emissions and microbial community dynamics. Soil Biol. Biochem. 110, 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.02.013 (2017).

Shi, Y. et al. Shift in nitrogen transformation in peatland soil by nitrogen inputs. Sci. Total Environ. 764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142924 (2021).

Zhang, T. et al. Environmental factors and dissolved organic carbon content in a Jinchuan peatland. Acta Ecol. Sin. 36, 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2016.04.001 (2016).

Li, Y., Wang, X., He, C., Jiang, H. & Sheng, L. Multi-environment factors dominate plant community structure and diversity in an ombrotrophic Bog: the water level is the main regulating mechanism. Front. Environ. Sci. 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1032068 (2022).

Tuittila, E. S. et al. Methane dynamics of a restored cut-away peatland. Glob. Change Biol. 6, 569–581. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00341.x (2000).

Zhang, H. et al. Annual methane emissions from degraded alpine wetlands in the Eastern Tibetan plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 657, 1323–1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.443 (2019).

Wang, W., Chen, Q., Huang, H. & Xie, Y. Effects of fallow season water and straw management on methane emissions and associated microorganisms. Agronomy-Basel 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14102302 (2024).

Rodriguez, A. F., Daroub, S. H., Gerber, S., Jennewein, S. P. & Singh, M. P. Water management effect on soil oxidation, greenhouse gas emissions, and nitrogen leaching in drained peat soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 85, 814–828. https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20247 (2021).

Kwon, M. J. et al. Plants, microorganisms, and soil temperatures contribute to a decrease in methane fluxes on a drained Arctic floodplain. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 2396–2412. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13558 (2017).

Peng, C., Li, H., Yang, N. & Lu, M. A. Comparison of greenhouse gas emission patterns in different water levels in peatlands. Water 16, 985 (2024).

Wang, X. Study on the dynamics and the main influencing factors of CO2 emission in a Changbai mountain peatland. (2022).

Shi, Y. Effects of Nitrogen Input on Carbon and Nitrogen Transformations in Peatlands. (Northeast Normal University, 2019).

Mastny, J., Barta, J., Kastovska, E. & Picek, T. Decomposition of peatland DOC affected by root exudates is driven by specific R and K strategic bacterial taxa. Sci. Rep. 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97698-2 (2021).

Leifeld, J., Klein, K. & Wust-Galley, C. Soil organic matter stoichiometry as indicator for peatland degradation. Sci. Rep. 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64275-y (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Drainage-Driven loss of carbon sequestration of a temperate peatland in Northeast China. Ecosystems 27, 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-023-00883-9 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. Drainage and afforestation more strongly affect soil microbial composition in Fens than bogs of subtropical moss peatlands. Sustainability 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198621 (2024).

Urbanova, Z. & Barta, J. Effects of long-term drainage on microbial community composition vary between peatland types. Soil Biol. Biochem. 92, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.09.017 (2016).

Toberman, H. et al. Long-term drainage for forestry inhibits extracellular phenol oxidase activity in Finnish boreal mire peat. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 61, 950–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2010.01292.x (2010).

Munford, K. E. et al. How arsenic contamination influences downslope wetland plant and microbial community structure and function. Sci. Total Environ. 876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162839 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Insight into the microbial community of denitrification process using different solid carbon sources: not only bacteria. J. Environ. Sci. 144, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2023.08.008 (2024).

Kunarso, A. et al. Land use change alters carbon composition and degree of decomposition of tropical peat soils. Mires Peat. 30. https://doi.org/10.19189/MaP.2023.OMB.Sc.2121334 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Shifting relationships between SOC and molecular diversity in soils of varied carbon concentrations: evidence from drained wetlands. Geoderma 433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116459 (2023).

Peltoniemi, K., Fritze, H. & Laiho, R. Response of fungal and actinobacterial communities to water-level drawdown in boreal peatland sites. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41, 1902–1914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.06.018 (2009).

Ali, S. R. A., Isa, M. N. M., Safari, S., Maidin, M. S. T. & Ibrahim, S. A. Eukaryotic biodiversity in mixed peat ecosystems in Sarawak, Malaysia. J. Oil Palm. Res. 30, 429–450. https://doi.org/10.21894/jopr.2018.0023 (2018).

Amha, Y., Bohne, H. & Alsanius, B. Patterns of fungal and bacterial carbon mineralization across Northern European peatlands. Geomicrobiol J. 32, 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490451.2015.1025318 (2015).

Xue, D. et al. How do water table drawdown, duration of drainage, and warming influence greenhouse gas emissions from drained peatlands of the Zoige plateau?? Land. Degrad. Dev. 32, 3351–3364. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4013 (2021).

Asemaninejad, A., Thorn, R. G., Branfireun, B. A. & Lindo, Z. Climate change favours specific fungal communities in boreal peatlands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 120, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.01.029 (2018).

Ingle, R. et al. Upscaling methane fluxes from peatlands across a drainage gradient in Ireland using planetscope imagery and machine learning tools. Sci. Rep. 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38470-6 (2023).

Wang, H. Y. et al. Microbial communities and functions are structured by vertical geochemical zones in a Northern peatland. Sci. Total Environ. 950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175273 (2024).

Prasitwuttisak, W., Hoshiko, Y., Maeda, T., Haraguchi, A. & Yanagawa, K. Microbial community structures and methanogenic functions in wetland peat soils. Microbes Environ. 37. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME22004 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Molecular mechanisms of water table Lowering and nitrogen deposition in affecting greenhouse gas emissions from a Tibetan alpine wetland. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 815–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13467 (2017).

Kwon, M. J. et al. Disproportionate microbial responses to decadal drainage on a Siberian floodplain. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5124–5140. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15785 (2021).

Keuschnig, C. et al. Reduced methane emissions in former permafrost soils driven by vegetation and microbial changes following drainage. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 3411–3425. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16137 (2022).

Weil, M. et al. Long-Term rewetting of three formerly drained peatlands drives congruent compositional changes in Pro- and eukaryotic soil microbiomes through environmental filtering. Microorganisms 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8040550 (2020).

Ma, K. & Lu, Y. Regulation of microbial methane production and oxidation by intermittent drainage in rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 75, 446–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.01018.x (2011).

Li, Y., Sun, Y., Li, L. & Yuan, Z. Acclimation of acid-tolerant methanogenic propionate-utilizing culture and microbial community dissecting. Bioresour. Technol. 250, 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.11.034 (2018).

Wormald, R. M., Rout, S. P., Mayes, W., Gomes, H. & Humphreys, P. N. Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis under alkaline conditions. Front. Microbiol. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.614227 (2020).

Gorres, C. M., Conrad, R. & Petersen, S. O. Effect of soil properties and hydrology on archaeal community composition in three temperate grasslands on peat. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6941.12115 (2013).

Lin, F., Zuo, H., Ma, X. & Ma, L. Comprehensive assessment of nitrous oxide emissions and mitigation potentials across European peatlands. Environ. Pollut. 301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119041 (2022).

Swails, E. et al. Soil nitrous oxide and methane fluxes from a land-use change transition of primary forest to oil palm in an Indonesian peatland. Biogeochemistry 167, 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-023-01070-7 (2024).

Berendt, J. & Wrage-Moennig, N. Denitrification is not necessarily the main source of n < sub > 2 o from rewetted Fens. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 23, 3705–3713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-023-01291-7 (2023).

Gudmundsson, J. et al. Low nitrous oxide fluxes from mineral affected peatland soils in Iceland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2024.109247 (2024).

Silins, U. Post-drainage Peatland Moisture and Aeration Dynamics. (University of Alberta, 1997).

Yang, Q. N. et al. Hydroclimate controls of the distribution and abundance of mosses in Hani Mire, Northeast China: modern vegetation survey and peat-core analysis. Quatern. Int. 528, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2019.09.026 (2019).

Bu, Z. et al. Performance of four mosses in a reciprocal transplant experiment: implications for peatland succession in NE China. J. Bryology 35, 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743282013y.0000000063 (2013).

Yang, Y. H. et al. Responses of the germinability of Sphagnum spores in peat to drainage in Baijianghe peatland, China. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao = J. Appl. Ecol. 31, 1707–1714. https://doi.org/10.13287/j.1001-9332.202005.002 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Response of C:N:P stoichiometry to long-term drainage of peatlands: evidence from plant, soil, and enzyme. Sci. Total Environ. 919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170688 (2024).

Yang, T. et al. Combination of plant species and water depth enhance soil quality in near-natural restoration of reclaimed wetland. Ecol. Eng. 208, 107376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2024.107376 (2024).

Feng, L. et al. Continuous waterlogging May not facilitate germinability maintenance of < i > sphagnum spores. Wetlands 37, 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-017-0936-y (2017).

Kalembasa, S. J. & Jenkinson, D. S. A comparative study of titrimetric and gravimetric methods for the determination of organic carbon in soil. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 24, 1085–1090 (1973).

Karki, S., Elsgaard, L., Kandel, T. P. & Laerke, P. E. Full GHG balance of a drained Fen peatland cropped to spring barley and Reed Canary grass using comparative assessment of co < sub > 2 fluxes. Environ. Monit. Assess. 187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-014-4259-7 (2015).

Karki, S., Elsgaard, L., Audet, J. & Laerke, P. E. Mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions from Reed Canary grass in paludiculture: effect of groundwater level. Plant. Soil. 383, 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-014-2164-z (2014).

Lin, Q. et al. Effects and mechanisms of land-types conversion on greenhouse gas emissions in the yellow river floodplain wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152406 (2022).

John, K. et al. Earthworms offset straw-induced increase of greenhouse gas emission in upland rice production. Sci. Total Environ. 710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136352 (2020).

Zhang, H. L. et al. Emissions of ch < sub > 4 and n < sub > 2 o under different tillage systems from Double-Cropped paddy fields in Southern China. Plos One 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065277 (2013).

Naser, H. M., Nagata, O., Sultana, S. & Hatano, R. Carbon Sequestration and Contribution of CO < sub > 2, CH < sub > 4 and N < sub > 2 O Fluxes to Global Warming Potential from Paddy-Fallow Fields on Mineral Soil Beneath Peat in Central Hokkaido, Japan. Agriculture-Basel 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10010006 (2020).

Rabbai, A. et al. Fertilization-induced greenhouse gas emissions partially offset carbon sequestration during afforestation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2024.109577 (2024).

IPCC. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. 2, 2391. (2021).

Acknowledgements