Abstract

Hyponatremia is the most common electrolyte disorder in cancer patients and is associated with a worse outcome. This finding has also been reported in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). We have previously demonstrated that low extracellular sodium concentrations ([Na+]) increase cell proliferation and invasion in several human cancer cell lines. The aim of the present study was to evaluate in vitro the effects of mild [Na+] alterations on two mRCC cell lines, ACHN and Caki-1. After growth in reduced extracellular [Na+], we observed that even mild reductions of [Na+] significantly enhanced different key cancer cell features, including proliferation, invasion and migration. Furthermore, we observed a reduction in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in low [Na+], with a significant increase of the antioxidant Nrf2/HMOX-1 pathway. Since an excess of ROS causes cell death, this finding clarifies the role of Nrf2/HMOX-1 in maintaining the balance between oxidant and antioxidant species in the tumor environment, promoting cell survival. Although further clinical studies are needed, aiming for instance to determine whether serum [Na+] correction improves the outcome of patients with mRCC, our findings suggest that attention should be deserved to serum [Na+] in this setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is known for its aggressive nature and resistance to conventional chemotherapy and radiation therapies1. For this reason, the survival rate of patients with advanced RCC is suboptimal2,3,4. This highlights the critical need to explore novel therapeutic strategies and to deepen our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying RCC progression and metastasis.

One promising area of exploration in cancer research is the role of the tumor microenvironment, specifically its ionic composition, which can profoundly influence cancer cell behavior. Among various ions, sodium (Na+) plays a crucial role in maintaining cellular homeostasis, influencing processes such as cell volume regulation, signal transduction, and metabolism5. Hyponatremia (i.e. serum Na+ concentration ([Na+]) below 135 mEq/L) is the most frequently Na+ imbalance encountered in different clinical contexts, including oncological ones6,7.

In cancer patients, this electrolyte disorder is described as an independent prognostic factor associated with a reduction in progression-free and overall survival rates8,9,10,11. Conversely, the normalization of low serum [Na+] has been demonstrated to exert a beneficial influence on clinical outcomes, preventing clinical complications and reducing mortality12,13,14.

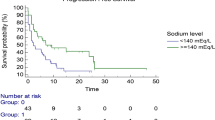

Hyponatremia is detected in about 15% of patients with metastatic RCC (mRCC)15 and has been linked to a worse prognosis and shorter cancer-specific survival15,16. Recently, serum [Na+] that are in the range of normality, yet < 140 mEq/L, have also been associated with poorer outcomes in mRCC patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors or nivolumab therapy17,18. Preclinical studies are currently investigating how [Na+] impact cancer progression and immune response modulation, potentially leading to new combined therapeutic strategies in the near future19,20,21.

In vitro and in vivo studies have suggested that alterations in extracellular [Na+] can significantly affect cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and migration22,23,24, and promote resistance to anticancer treatment25. However, the specific effects of low [Na+] on renal cancer cells, particularly mRCC, remain poorly understood.

This study aims to investigate the impact of reduced extracellular [Na+] on the proliferation, invasiveness, and oxidative stress response of two mRCC cell lines. By systematically varying the [Na+] in the cell culture medium, we aimed to elucidate how these conditions influence key cellular processes and molecular pathways associated with mRCC progression. The objective of this comprehensive analysis is to identify potential mechanisms by which low [Na+] may modulate mRCC cell behavior, providing insights that could be useful for future therapeutic approaches.

Results

Cell proliferation and viability in low [Na+]

Using the MTS proliferation assay, cell viability appeared significantly increased in ACHN and Caki-1 cell lines in low [Na+] when compared to the normal [Na+] for these cells (153 mM) (Fig. 1a). In particular, ACHN demonstrated a significant increase in cell proliferation already at a [Na+] of 141 mM, which persisted as the [Na+] decreased (Fig. 1a). In Caki-1, a significant difference in cell viability was observed starting from a [Na+] of 135 mM (Fig. 1a). In agreement with these results, the analysis of cell cycle showed a trend toward an increased percentage of cells in both G0/G1 and S phase, whereas there was a reduced number of cells, yet not statistically significant, in G2/M phase in low [Na+] compared to controls in both cell lines (Fig. 1b).

Analysis of cell proliferation and viability in low [Na+] (a) Cell proliferation of ACHN and Caki-1 was assessed by MTS assay. The reported images are representative of cell growth at different [Na+] (magnification 100×). Results are expressed as mean ± SE of the optical density (OD) at 490 nm/well normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01). (b) Flow cytometry cell cycle analysis of ACHN and Caki-1. Results are expressed as percentage (%) of cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M phases (mean ± SE). (c) Western blot analysis of pAkt/Akt, pERK/ERK, cyclin D1 and PCNA protein expression at different [Na+]. Results are expressed as the number of positive pixels normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01). Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1c.

To further investigate this finding, the expression of proteins involved in intracellular signaling, including Akt and ERK1/2 and their active form pAkt and pERK1/2, cyclin D1 and PCNA, was assessed by Western blot analysis. The results showed an increase in the expression of the pAkt/Akt ratio in both cell lines (Fig. 1c). In particular, the increase in pAkt/Akt was statistically significant from a [Na+] of 147 mM for ACHN and from 141 mM for Caki-1, which are [Na+] mildly reduced for these cells. Accordingly, the expression of pERK/ERK was also enhanced in both cell lines. Furthermore, a significant increase in the expression of cyclin D1 and PCNA proteins was observed in both cell lines at different [Na+] compared to 153 mM (Fig. 1c).

Cell invasion and cell migration in low [Na+]

A significant increase in invasive capacity was observed in both cell lines cultured in low extracellular [Na+] (Fig. 2). In particular, there was a statistically significant difference at [Na+] of 141 mM and 135 mM for ACHN, and from the [Na+] of 135 mM for Caki-1 compared to control (Fig. 2).

Analysis of cell invasion in low [Na+] Cell invasion of ACHN and Caki-1 was assessed by Transwell invasion assay. The reported images are representative of cell invasion at different [Na+] (magnification 100×). Results are expressed as the optical density (OD) at 550 nm/well normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.05).

Accordingly, cell migration was increased in low [Na+] in both cell lines, as assessed by the wound healing assay (Fig. 3a) and by transwell migration assay (Fig. 3b).

Analysis of cell migration in low [Na+] (a, b) Cell migration of ACHN and Caki-1 was assessed by wound healing assay (a) and by Transwell migration assay (b). The reported images are representative of cell migration at the time of the creation of the wound (T0) and after 24 h (T24), and of cell migration using transwell assay at different [Na+] (magnification 100×). Results are expressed as the % area of wound closed and as the optical density (OD) at 550 nm/well normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01 and ***p ≤ 0.001).

In accordance with data regarding invasiveness and migration, the zymography assay showed a notable increase in the protein expression of MMP2 and MMP9 when ACHN and Caki-1 were maintained in low [Na+] (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, Western blot analysis of RhoA, ROCK1 and Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin (ERM) proteins, both in the active and the inactive form, demonstrated an increase in the protein expression levels in both cell lines cultured in low [Na+] compared to 153 mM (Fig. 4b).

Expression analysis of MMP2, MMP9, RhoA, ROCK1 and pERM/ERM proteins in low [Na+] (a) MMP2 and MMP9 proteins expression was assessed by Zymography assay. The reported images are representative of MMP2 and MMP9 expression at different [Na+]. Results are expressed as the number of positive pixels normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.5 and **p ≤ 0.01). Original gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4a. (b) Western blot analysis of RhoA, ROCK1 and pERM/ERM protein expression at different [Na+]. Results are expressed as the number of positive pixels normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.05). Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4b.

Interestingly, pH measurements revealed a reduction of cell culture medium pH as [Na+] decreased in both cell lines, indicating an acidification of the cell culture medium, which is in agreement with the increase in cell viability and metastatic processes (Table 1).

Oxidative stress in low [Na+]

A reduction in oxidative stress was observed in both cell lines when cultured in low [Na+]. Indeed, both immunofluorescence (Fig. 5a) and cytometric (Fig. 5b) analysis of the CellROX assay showed a decrease in the amount of ROS in ACHN and Caki-1 cells, compared to the controls.

Analysis of oxidative stress in low [Na+] (a, b) Reactive oxidative species (ROS) expression levels were assessed by CellROX Deep Red Flow Cytometry Assay Kit by immunofluorescence (a) and cytometric analysis (b). (a) The reported images showed the double stain of nuclei with DAPI (blue) and ROS (red) and are representative of ROS expression at different [Na+] (magnification 200×). Results are expressed as CellROX integrated density normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.5 and **p ≤ 0.01). (b) Representative gating strategy of CellROX Deep Red FACS staining for assessment of ROS quantification at different [Na+]. Results are expressed as CellROX mean signal intensity normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.5, **p ≤ 0.01 and ***p ≤ 0.001). (c) Relative mRNA expression of HIF-1α, NQO1, HMOX-1 and MDM2 at different [Na+]. Results are expressed as the relative mRNA level normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.5). (d) Western blot analysis of Nrf2, HMOX-1 and Bcl-2 protein expression at different [Na+]. Results are expressed as the number of positive pixels normalized versus [Na+] 153 mM (*p ≤ 0.5). Original blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5d.

In agreement with these results, the RNA levels of Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 Subunit Alpha (HIF-1α) was decreased (Fig. 5b), whereas the RNA levels of NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (quinone) 1 (NQO1) and heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX-1) (Fig. 5c) were increased in low [Na+] compared to 153 mM. Similarly, the protein expression of Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and HMOX-1 (Fig. 5d) were also increased in low [Na+].

In addition, the RNA levels of the MDM2 oncogene (Fig. 5c) and the protein expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 were increased in both cell lines (Fig. 5d).

Discussion

Epidemiological data have indicated a relationship between chronic hyponatremia and a worse prognosis in cancer patients, though a direct correlation between this electrolyte imbalance and tumor biology has not been clearly established8,9,10,15,19. In agreement with the clinical data, recent studies demonstrated for the first time that the reduction of extracellular [Na+] can alter the homeostasis of chronic myeloid leukemia, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, neuroblastoma and microcitoma human cancer cell lines and favor tumor progression22,23,24. Furthermore, recent clinical studies have demonstrated that in patients with mRCC serum [Na+] < 140 mM, which fall within the normal range, can negatively affect the response to specific therapies17,18.

Hence, in the present study we evaluated for the first time the impact of reduced extracellular [Na+] on proliferation, invasiveness, and oxidative stress response of two mRCC human cell lines, ACHN and Caki-1.

In accordance with previous in vitro studies22,23, we found that low [Na+], even when mildly reduced for these cells (i.e. 147 mM), significantly enhance some of the pivotal aspects of tumor progression (i.e. cell proliferation, invasion, migration and resistance to oxidative stress).

In particular, we observed an increased viability in both cell lines grown in reduced [Na+]. Furthermore, a trend to an increase in the percentage of cells in the G0/G1 and S phases of the cell cycle and to a decrease in the percentage of cells in the M phase was also observed. These results indicate that in low [Na+] there is a greater number of cells in active proliferation, that are duplicating their genome, compared to normal [Na+] (153 mM). These effects were accompanied by a higher pAkt/Akt and pERK/ERK ratio, cyclin D1 and PCNA expression. Akt is a serine/threonine kinase that plays a key role in cell survival and proliferation, and its overexpression or activation by mutations is a hallmark of numerous human cancers26. Similarly, overexpression of the active form of the mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK has also been correlated with increased tumor progression through the activation of processes such as proliferation, survival, invasion and migration27. In the presence of low [Na+], total Akt and ERK1/2 remained unaltered, whereas the amount of the phosphorylated (Ser473) active form pAkt and the phosphorylated (Thr202/Tyr204) active form pERK1/2 were increased in both cell lines. These results are in agreement with the increased protein expression of cyclin D1, a crucial regulator of the cell cycle, which facilitates uncontrolled cell proliferation and the transition from the quiescent G0 phase to the entry into the cell cycle (G1 phase)28. In addition, PCNA expression was also increased in cells grown in low [Na+] compared to 153 mM. Notably, PCNA is an essential protein in the DNA duplication process as a cofactor of DNA polymerase, but it also interacts with the G1/S phase cyclins, which promote cell cycle progression29,30. As already demonstrated, these findings suggest that low extracellular [Na+], and by extension a low [Na+] tumor microenvironment, activates intracellular signaling pathways associated with proliferation and survival.

It is known that invasion and migration are essential mechanisms for tumor cells metastatisation and are indices of tumor aggressiveness. Using invasion and migration assays, we found a significant increase in both processes in ACHN and Caki-1 cells, when grown in low [Na+]. The increased invasiveness is in agreement with the observed significant increased expression of MMP2 and MMP9, which are enzymes implicated in the degradation of the extracellular matrix and in the metastasis process31. To further investigate the alteration of cell invasiveness and migration, we analyzed the expression of RhoA, ROCK1 and ERM proteins. RhoA, a small GTPase involved in cytoskeleton regulation, and ROCK1 are key regulators of several cellular processes, including migration and invasiveness32. ERM proteins are substrates of RhoA/ROCK1 and act as mediators between the plasma membrane and actin, thus playing a key role in adhesion and migration processes33,34. Western blot analysis demonstrated an increased expressiom of RhoA, ROCK1 and pERM/ERM ratio in low [Na+] compared to 153 mM, suggesting that low extracellular [Na+] promotes cancer cells invasion and migration through this pathway. Furthermore, the reduction of [Na+] was accompanied by a decrease in pH, which correlates with an increase in cell viability35. In particular, this pH reduction was more evident in ACHN cells than in Caki-1 cells, probably due to their higher proliferation rate and faster metabolic rate. Decreased extracellular pH (< 7.4) is also strictly necessary in the metastasis process36. It has been shown that in the presence of acidic extracellular pH there is an increase in secretion and activity of MMPs, which degrade the extracellular matrix to allow cancer cells to move and invade other tissues37. Collectively, these findings indicate that low [Na+] promote the metastatic capacity of ACHN and Caki-1 cells.

It is known that the increase in oxidative stress is an essential factor in tumor proliferation and invasion. However, at the same time, an excessive level of ROS can damage and lead to the death of tumor cells38. Both immunofluorescence and cytometric analysis showed a decrease in the amount of ROS in ACHN and Caki-1 cells grown in low [Na+] compared to control (153 mM). To further analyze this aspect, the expression of genes involved in the cellular redox state, such as HIF-1α, Nrf2, NQO1 and HMOX-1, was analyzed. In physiological conditions, HIF-1α, which is activated by hypoxia, and Nrf2, which is activated by the presence of oxidative stress as an antioxidant factor, protect cells from hypoxic and oxidative damage. In cancer, their interaction may be crucial for tumor survival and progression39,40. Indeed, cancer cells have to cope with both stresses simultaneously, and co-activation of HIF-1α and Nrf2 allows cancer cells to adapt better to an adverse tumor microenvironment39,40. Under hypoxic conditions, both HIF-1α and Nrf2 can increase the expression of antioxidant genes to promote cell survival in the presence of increased oxidative stress41. These genes include NQO1 and HMOX-1, which in principle reduce ROS levels, but also anti-apoptotic genes40.

In agreement with the decrease in the amount of ROS, we showed a decrease in HIF-1α expression and an increase in Nrf2 in both cell lines in low [Na+]. Although Nrf2 is mostly defined as an oxidative stress response transcription factor, it also plays a key role in other cellular processes, i.e. regulation of metabolism, inflammation, autophagy, and immune responses. Therefore, whereas under physiological conditions it plays a protective role in response to oxidative stress, its activation in the tumor context may promote cancer development41. Likewise, we observed an increased expression of antioxidant genes activated by Nrf2, such as NQO1 and HMOX-1, in both cell lines compared to 153 mM. It is known that HMOX-1 is involved in the proliferation, survival and angiogenesis pathways42,43, and previous studies have also demonstrated that its expression was elevated in RCC cell lines following the activation of the Ras-Raf-ERK pathway. Consequently, an increase in cell survival and a decrease in the apoptotic process were observed44,45.

An escape from the apoptotic process is a further hallmark of tumor progression46. In cancer, the MDM2 oncogene and the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 are crucial for their role in down-regulating cell apoptosis in favor of survival. Indeed, an overexpression of MDM2 can reduce p53 expression via the negative feedback pathway and inhibits apoptosis, whereas the activation of Bcl-2 induces tumor initiation, progression and chemo-resistance47. With regard to this issue, we found an elevated expression of both the MDM2 and Bcl-2 in ACHN and Caki-1 cell lines grown in reduced [Na+].

Several studies have shown that Nrf2 and HMOX-1 are up-regulated in tumor tissues, thus promoting a more aggressive phenotype42,43. Interestingly, Nrf2 and HMOX-1 have been considered possible targets in anti-cancer strategies48,49,50,51. Because of the dual role of the Nrf2/NQO1/HMOX-1 antioxidant pathway in physiological conditions and in cancer, further studies are needed to understand its role in tumorigenesis. Furthermore, studies that target inhibitors of different steps of the Nrf2/NQO1/HMOX-1 pathway could probably help to clarify the mechanism behind this process.

Altogether, our findings indicate that low [Na+], even when mildly reduced, may contribute to tumor progression through enhanced cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. In addition, a crucial role appears to be played by the balance between oxidant and antioxidant species, which remains to be further elucidated, as above mentioned. These results may provide an explanation to the clinical data obtained in cancer patients with serum [Na+] alterations8,9,10,11,15. In particular, with regard to mRCC, our results are in agreement with the observation that reduced serum [Na+] is independently and significantly associated with overall survival and disease-free survival8,11. The translational impact of our data appears to be reinforced by the already mentioned studies, which demonstrated that hyponatremia or, more recently, even serum [Na+] in the lower limit of the normal range, negatively affect the response to targeted therapies or immunotherapy in mRCC15,16,17,18. Admittedly, further clinical studies are needed, in order to clarify whether hyponatremia correction positively affects the response to therapies and the outcome of patients with mRCC, as demonstrated in other types of cancer13,14. Nevertheless, the data reported in this study further reinforce the idea that attention should be deserved to reduced serum [Na+] in cancer patients.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

ACHN and Caki-1 mRCC human cell lines were purchased from European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC, Salisbury, UK) and American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), respectively. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) culture medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) were purchased from Euroclone S.p.A. (Milan, Italy). CellTiter 96® Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, MTS assay) was purchased from Promega Corporation (Milan, Italy). CellROX Deep Red Flow Cytometry Assay Kit was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell culture and experimental protocol

ACHN and Caki-1 cells were cultured in DMEM complete medium (10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin), and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. To evaluated the effects of low [Na+], growth media with different [Na+] were prepared, as previously described22. Using a sodium-free DMEM 2X medium, growth media were prepared by adding different amounts of NaCl. The [Na+] of DMEM medium is 153 mM, which was used as the control [Na+]. To achieve the desired [Na+] (147, 141, 135, or 127 mM), distilled water, 0.9 mM NaH2PO4, 44 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM glucose, and the necessary amount of NaCl, were added. Osmolality was kept constant at 307.8 mOsm/Kg by adding mannitol to the medium. ACHN and Caki-1 cells were adapted to grow in media with different [Na+] by changing the culture medium daily. All experiments were performed after 7 days of growth in medium at the specific [Na+].

Analysis of cell proliferation and viability

ACHN and Caki-1 cells (104 cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and cultured in specific low Na+ medium for 48 h. After this time, MTS was added, as per manufacturer’ protocol. The luminescence was recorded with a Wallac multiplate reader (Perkin-Elmer, Milan, Italy) and the results were expressed as optical density (OD)/well normalized versus the OD/well of control.

Analysis of cell cycle

Cell cycle analysis was evaluated using propidium iodide (PI) (Miltenyi Biotec S.r.l., Bologna, Italy), as previously described52. After tripsinization, the cells were resuspended in complete medium and spun down at 1500 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was washed with wash buffer (PBS 1×/0.3%BSA/sodium azide) and transferred to an eppendorf tube. After centrifugation, 1 ml of cold 70% EtOH was added dropwise and kept on ice at 4 °C for 30 min. Then, the cells were washed twice with wash buffer and stained with 30 µl of 50 µg/ml PI + 100 µg/ml RNAse (per 5 * 105) cells for 20 min at room temperature, in the dark. After this time, 500 µl of wash buffer was added and the analysis was performed using a flow cytometry (MacsQuant instrument, Miltenyi Biotec S.r.l., Bologna, Italy). The results were analysed using the FlowLogic Solution 1.0 Software and expressed as percentage (%) of cells in the different phases of cell cycle (G0/G1, S and G2/M).

pH measurement

After 7 days of growth at different [Na+], the culture media were collected in falcon tubes and the pH was measured using a pH meter (Medidor PH BASIC 20, Crison Instruments, Modena, Italy).

Analysis of cell invasion

Fifty-thousand cells were seeded into a cell culture filter inserts (8 µm pore) (Corning® Costar® Transwell® cell culture inserts, Corning, NY, USA) coated with 0.3% BD Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in 500 µl of serum-free medium. The inserts were placed in a 24-well plate and 1 ml of complete medium was added to each well. After overnight (ON) incubation at 37 °C, the inserts were stained with crystal violet and the invaded cells were then observed under an optical microscope. Subsequently, the invaded cells were destained with an extraction buffer (acetic acid) and the staining mixture was measured by a spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer) at the OD of 560 nm. The results were expressed as OD/well normalized versus OD/well of control.

Wound healing assay

Fifty-thousand cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and allowed to grow to 100% confluence. Subsequently, a wound was created using sterile pipette tips. At this time (T0) and after 24 h (T24), microscopic images were captured with an optical microscope to assess the degree of wound contraction. The images were analyzed using the open-source cell image analysis software ImageJ- win64 Java 8 and the results were expressed as % area of wound closed (% area at T24-% area at T0).

Transwell migration assay

Twenty-thousand cells were seeded into a cell culture filter inserts (8 µm pore) (Corning® Costar® Transwell®) in 100 µl of serum-free medium in a 24-well plate and 600 µl of complete medium was added to each well. After overnight (ON) incubation at 37 °C, the cells were fixed with cold methanol at + 4 °C for 20 min, stained with crystal violet and observed using an optical microscope. After destaining with acetic acid, the staining mixture was measured by a spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer) at the OD of 560 nm. The results were expressed as OD/well normalized versus OD/well of control.

Zymography assay

Cell supernatants were separated by electrophoresis on a 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide 0.1% gelatin gel at 90 mV. The gel was washed twice with 2.5% Triton X-100 and with reaction buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM CaCl2, 200 mM NaCl and 1% Triton X-100) for 30 min, and incubated with reaction buffer ON at 37°. Subsequently, the gel was stained with 0.1% Coomassie blue and destained until unstained (white) bands, corresponding to MMP2 and MMP9, were visible. The unstained bands were quantified using the ImageJ-win64 Java 8 software and the results were expressed as number of positive pixels normalized versus positive pixels of control.

Analysis of oxidative stress

Cells were incubated with 1 μM CellROX Deep Red reagent for 30 min at 37 °C and DAPI for 5 min, protected from the light. Subsequently, cells were washed twice in PBS and fixed in 3.5% formaldehyde for 15 min. The analysis was conducted using a fluorescent microscope (AM6000, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). A total of five images for each sample were used in the analysis with the ImageJ-win64 Java 8 software. The results were expressed as integrated density normalized versus integrated density of control.

Analysis was also performed by flow cytometry (MacsQuant instrument, Miltenyi Biotec S.r.l.). After incubation with 1 µM CellROX Deep Red reagent for 30 min at 37 °C, the cells were washed three times with PBS 1x, trypsinized and resuspended in complete medium. The pellet was transferred to an eppendorf tube, washed twice and resuspended in PBS 1 × for the analysis. The results were expressed as mean intensity of CellROX positive cells normalized versus control. The analysis was performed using the FlowLogic Solution 1.0 Software.

Western blot analysis

Thirty μg of proteins were separated in 10% or 12% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Precast Gels (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA), transferred to a PVDF membrane using the Invitrogen™ Power Blotter System (15806162, Invitrogen Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) and blocked in 5% milk. The membranes were then incubated with specific primary antibodies ON at 4 °C: anti-Akt antibody (9272S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-P-Akt antibody (4058S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) antibody (#9102, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti- phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody (#4370, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-cyclin D1 antibody (04-1151, 1:500, Millipore), anti-PCNA antibody (#2586S, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-RhoA antibody (26C4, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-ROCK1 antibody (sc-17794, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin antibody (3142T, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Phospho-Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin antibody (#3149, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Nrf2 antibody (sc-365949, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-HMOX-1 antibody (SAB2108676, 1:1000, Sigma Aldrich, Sant Louis, MO, USA) and anti-Bcl-2 antibody (sc-7382, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After two washes in PBS with 1% Tween, the membranes were incubated with the specific secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (#7076, anti-mouse IgG or #7074, anti-rabbit IgG, Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h. Chemiluminescence images were acquired using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Imaging System (Biorad). Densitometric analyses were normalized using stain-free acquisitions with the ImageJ-win64 Java 8 software. The results were expressed as number of positive pixels normalized versus positive pixels of control.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

RNA extraction was conducted using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol and the total RNA concentration was measured with a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ND-1000, NanoDrop Technologie). The reverse transcription into cDNA was performed with the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents using random hexamers (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) with the following protocol: 10 min at 25 °C, 30 min at 48 °C, and 5 min at 95 °C. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of target genes was conducted using pre-developed TaqMan® Assays (Assay-On-Demand products, Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) for MDM2 (Hs01066930_m1, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and HIF-1α (Hs00153153_m1, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and using the QuantiNova® SYBR® Green PCR (208052, Qiagen, Hilde, Germany) for NQO1 (forward: GCCGAACACAAGAAGCTGGAAG, reverse: GGCAAATCCTGCTACGAGCACT) and HMOX-1 (forward: CCTCTGGAGATGACACCTGAG, reverse: GTGTTCCTCTGTCAGCATCACC). The RNA quantification was performed using the comparative Ct (cycle threshold) method, normalizing with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase RNA expression. The results were expressed as fold changes in target mRNA normalized versus control.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. The results were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 5.0 and are shown as mean ± SE (standard error). Comparisons were analyzed using the unpaired Student’s t-test (two groups), and p ≤ 0.05 means a statistically significant difference.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Supplementary materials and from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Rini, B. I. et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1116–1127. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA1816714 (2019).

Motzer, R. et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1289–1300. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2035716 (2021).

Choueiri, T. K. et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 829–841. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2026982 (2021).

Bernal, A., Zafra, M. A., Simón, M. J. & Mahía, J. Sodium homeostasis, a balance necessary for life. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/NU15020395 (2023).

Adrogué, H. J. & Madias, N. E. Hyponatremia. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1581–1589. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005253422107 (2000).

Donald, D. M., Sherlock, M. & Thompson, C. J. Hyponatraemia and the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIAD) in cancer. Endocr. Oncol. (Bristol, England) 2, R78–R89. https://doi.org/10.1530/EO-22-0056 (2022).

Vasudev, N. S. et al. Prognostic factors in renal cell carcinoma: Association of preoperative sodium concentration with survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1775–1781. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1721 (2008).

Huo, T.-I., et al. The MELD-Na is an independent short-and long-term prognostic predictor for hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective survey. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2008.01.015 (2008).

Sandfeld-Paulsen, B., Aggerholm-Pedersen, N. & Winther-Larsen, A. Hyponatremia as a prognostic factor in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 10, 651–661 (2021).

Jeppesen, A. N., Jensen, H. K., Donskov, F., Marcussen, N. & Von Der Maase, H. Hyponatremia as a prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 102, 867–872. https://doi.org/10.1038/SJ.BJC.6605563 (2010).

Corona, G. et al. Hyponatremia improvement is associated with a reduced risk of mortality: Evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One 10, e0124105. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124105 (2015).

Balachandran, K., Okines, A., Gunapala, R., Morganstein, D. & Popat, S. Resolution of severe hyponatraemia is associated with improved survival in patients with cancer. BMC Cancer 15, 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1156-6 (2015).

Berardi, R. et al. Prognostic models to predict survival in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line chemo- or targeted therapy. Oncotarget 7, 26916–26924. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.8309 (2016).

Schutz, F. A. B. et al. The impact of low serum sodium on treatment outcome of targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer Database Consortium. Eur. Urol. 65, 723–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.013 (2014).

Bellmunt, J, et al. Platinum priority-kidney cancer the impact of low serum sodium on treatment outcome of targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer Database Consortium. 731–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.013.

Roviello, G. et al. Prognostic value of normal sodium levels in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Front. Oncol. 12, 918413. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.918413 (2022).

Catalano, M. et al. Sodium levels and outcomes in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving nivolumab + supplemental content. JAMA Netw. Open 6, 2345185. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.45185 (2023).

Djamgoz, M. B. A. Hyponatremia and cancer progression: Possible association with sodium-transporting proteins. Bioelectricity 2, 14. https://doi.org/10.1089/BIOE.2019.0035 (2020).

Müller, D. N., Wilck, N., Haase, S., Kleinewietfeld, M. & Linker, R. A. Sodium in the microenvironment regulates immune responses and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41577-018-0113-4 (2019).

Mao, W., Zhang, J., Körner, H., Jiang, Y. & Ying, S. The emerging role of voltage-gated sodium channels in tumor biology. Front. Oncol. 9, 427250. https://doi.org/10.3389/FONC.2019.00124/BIBTEX (2019).

Marroncini, G. et al. Effects of low extracellular sodium on proliferation and invasive activity of cancer cells in vitro. Endocrine 67, 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-019-02135-0 (2020).

Marroncini, G. et al. Low sodium and tolvaptan have opposite effects in human small cell lung cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 537, 111419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2021.111419 (2021).

Marroncini, G. et al. Hyponatremia promotes cancer growth in a murine xenograft model of neuroblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242316680 (2023).

Naldi, L. et al. Effects of reduced extracellular sodium concentrations on cisplatin treatment in human tumor cells: The role of autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25084377 (2024).

Revathidevi, S. & Munirajan, A. K. Akt in cancer: Mediator and more. Semin. Cancer Biol. 59, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.06.002 (2019).

Ullah, R., Yin, Q., Snell, A. H. & Wan, L. RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer evolution and treatment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 85, 123–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.05.010 (2022).

Montalto, F. I. & De Amicis, F. Cyclin D1 in cancer: A molecular connection for cell cycle control, adhesion and invasion in tumor and stroma. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9122648 (2020).

Strzalka, W. & Ziemienowicz, A. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): A key factor in DNA replication and cell cycle regulation. Ann. Bot. 107, 1127–1140. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcq243 (2011).

Juríková, M., Danihel, Ľ, Polák, Š & Varga, I. Ki67, PCNA, and MCM proteins: Markers of proliferation in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Acta Histochem. 118, 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acthis.2016.05.002 (2016).

Cabral-Pacheco, G. A. et al. The roles of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249739 (2020).

Ridley, A. J. RhoA, RhoB and RhoC have different roles in cancer cell migration. J. Microsc. 251, 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmi.12025 (2013).

Clucas, J. & Valderrama, F. ERM proteins in cancer progression. J. Cell Sci. 127, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.133108 (2014).

Guan, R. et al. Advances in the studies of roles of Rho/Rho-kinase in diseases and the development of its inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 70, 613–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.10.048 (2013).

Zheng, T., Jäättelä, M. & Liu, B. PH gradient reversal fuels cancer progression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 125, 105796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2020.105796 (2020).

Webb, B. A., Chimenti, M., Jacobson, M. P. & Barber, D. L. Dysregulated PH: A perfect storm for cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 671–677 (2011).

Bourguignon, L. Y. W., Singleton, P. A., Diedrich, F., Stern, R. & Gilad, E. CD44 interaction with Na+-H+ exchanger (NHE1) creates acidic microenvironments leading to hyaluronidase-2 and Cathepsin B activation and breast tumor cell invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26991–27007. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M311838200 (2004).

Chiang, S.-K., Chen, S.-E. & Chang, L.-C. A dual role of heme oxygenase-1 in cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20010039 (2018).

Zimta, A.-A. et al. The role of Nrf2 activity in cancer development and progression. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11111755 (2019).

Bae, T., Hallis, S. P. & Kwak, M.-K. Hypoxia, oxidative stress, and the interplay of HIFs and NRF2 signaling in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 56, 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-024-01180-8 (2024).

He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134777.

Furfaro, A. L. et al. The Nrf2/HO-1 axis in cancer cell growth and chemoresistance. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 1958174. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1958174 (2016).

Loboda, A., Jozkowicz, A. & Dulak, J. HO-1/CO system in tumor growth, angiogenesis and metabolism—targeting HO-1 as an anti-tumor therapy. Vascul. Pharmacol. 74, 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vph.2015.09.004 (2015).

Banerjee, P. et al. The heme oxygenase-1 protein is overexpressed in human renal cancer cells following activation of the Ras-Raf-ERK pathway and mediates anti-apoptotic signal. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 33580–33590. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.248401 (2011).

Banerjee, P. et al. Heme oxygenase-1 promotes survival of renal cancer cells through modulation of apoptosis- and autophagy-regulating molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 32113–32123. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.393140 (2012).

Evan, G. I. & Vousden, K. H. Proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis in cancer. Nature 411, 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/35077213 (2001).

Chang, M., Gao, F., Chen, J., Gnawali, G. & Wang, W. MDM2-BCL-X(L) PROTACs enable degradation of BCL-X(L) and stabilization of P53. Acta Mater. Medica 1, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.15212/amm-2022-0022 (2022).

Yamaguchi, Y. et al. Nrf2 gene mutation and single nucleotide polymorphism Rs6721961 of the Nrf2 promoter region in renal cell cancer. BMC Cancer 19, 1137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6347-0 (2019).

Crisman, E. et al. KEAP1-NRF2 protein–protein interaction inhibitors: Design, pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential. Med. Res. Rev. 43, 237–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/med.21925 (2023).

Fang, J., Seki, T. & Maeda, H. Therapeutic strategies by modulating oxygen stress in cancer and inflammation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 61, 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2009.02.005 (2009).

Mingote, P. A. et al. Expression of Hemeoxygenase-1 and clear cell renal cell carcinoma aggressiveness. Arch. Esp. Urol. 73, 794–802 (2020).

Melica, M. E. et al. Differentiation of crescent-forming kidney progenitor cells into podocytes attenuates severe glomerulonephritis in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, 3277. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abg3277 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the European Union – Next Generation EU. National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) – Mission 4, Component 2 – Investment 1.4 – CUP B13C22001010001 and from the Research Grant from the University of Florence (RICATEN2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.N., M.C., M.E.M., A.P. and G.R. conceived and designed the project, and drafted the main text. L.N., M.C., M.E.M., S.P., D.P. and I.L. acquired and analyzed data and performed the statistical analysis. A.P. and G.R. obtained fundings and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naldi, L., Catalano, M., Melica, M.E. et al. Effects of reduced extracellular sodium on proliferation and invasive activity of renal cell carcinoma cell lines. Sci Rep 15, 8067 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92674-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92674-6