Abstract

This research aims to design a high-temperature wear resistance cobalt-based coating of hot-end parts as protective coating. The cobalt-based matrix coatings were reinforced by NiCrAlY and different contents of TiC (6.0, 8.0 and 10.0 wt%) using laser cladding technology. Some efforts were made to explore the influence of TiC on the microstructure, hardness and wear behavior of prepared coatings. The wear behavior of coatings was done via a ball-on-disk wear machine under room temperature -800 °C. The results showed that NiCrAlY decomposed and formed γ-Co(fcc) and β-NiAl phases. The hardness of coatings with TiC was reinforced due to the fine-grain strengthening and dispersion strengthening. The friction coefficients of reinforced coatings were destroyed due to the TiC particle and in-situ synthetized ceramic particles, whereas the wear resistance of coatings with TiC was enhanced. There existed an optimal content of TiC for the wear resistance of Co-NiCrAlY-TiC coatings. The coating with 8.0 wt% TiC had a satisfactory tribologcial performance at test temperatures. It was ascribed to the moderate hardness and in-situ synthetized solid lubricants, as well as the tribo-layer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The core parts have an important influence on the service life of aircraft engine, which need to endure the high temperature and high load under oil-free conditions1,2, leading to the wear failure of surface or interface of moving parts. In order to improve the high temperature service life of moving parts, it is ideal that a wear resistant coating is prepared on the working surface of moving parts without changing the properties of matrix. Cobalt alloys possess high melting point, high strength, low thermal expansion coefficient, corrosion resistance, etc. as compared with nickel alloys3,4. And therefore, cobalt alloys are ideal wear resistance coatings for moving parts at elevated temperature, which has been extensively explored in various industrial fields4,5. Additionally, the preparation technology is also a key index that influences the microstructure and service life of wear resistant coatings. Among different surface treatment technologies, the laser cladding technology is suitable for depositing wear resistant coatings over insufficient friction surfaces of moving parts due to its advantages such as high efficiency, low dilution, metallurgical bonding, etc., which has been employed to prepare different kinds of coatings6,7. Thus, it is reasonable to fabricate a coating with high wear resistance over moving parts using laser cladding technology to improve the service life of equipment at elevated temperature.

Mostly importantly, the Stellite alloys as cobalt alloys are famous high-temperature alloy material6,8,9. With the rapid increase of power of engines, the Stellite alloys are characterized by the insufficient wear resistance and low hardness at high temperature under multi-factor coupling action, so the Stellite alloys coating can no longer meet the wear resistance requirement at different working conditions. It is imperative to develop a new cobalt-based coating material with better performance. To solve this problem, some scholars had made great efforts to explore some coating systems of cobalt-matrix coatings10,11,12. Encalada et al. investigated the wear properties of Cr3C2 reinforced Stellite 6 coatings at room temperature, 200 and 300 °C13. The reinforced coating had lower wear rates than Stellite 6 because of high hardness. However, the stability of friction coefficient of reinforced coating was poorer than that of unreinforced Stellite 6 due to the frictional effect of ceramic particle. Jiang et al. studied the effect of B4C on the wear performance of CoCrNiMo matrix coatings at room temperature14. They found that the coatings containing 4.2 wt% B4C had better tribological performance. In summary, the addition of hard ceramic particles is a feasible method to strengthen the tribology performance of cobalt-based coatings4,5,11. Especially, the friction reduction and wear resistance of prepared coatings need to reach a compromise each other, so the optimized content of hard ceramic phase in coatings is also an important issue. Meanwhile, it is necessary to investigate the wear behavior of cobalt matrix coating within a wide range of temperature in order to expand the applications of coatings.

In current research, the Co powder was selected as matrix of coatings. NiCrAlY and different contents of TiC powders were used to strengthen the tribological performance of cobalt-matrix coatings from room temperature to 800 °C. The designed coatings were fabricated by laser cladding. The wear tests were carried out by a ball-on-disk wear tester starting from room temperature (25 °C) to 800 °C. The hardness, microstructure and tribological properties of specimens were accessed. The wear mechanism of specimens was explored according to the analysis of microstructure, elemental distribution and wear tracks of coatings in detail.

Experimental details

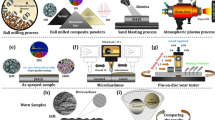

The feedstocks used in this study were the commercially available Co (purity 99.0%), NiCrAlY (purity 99.4%) and TiC (purity 99.3%) powder that were purchased from the Aladdin Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China. The sizes of different powders were calculated by using Nano Measurer software 1.2 (https://nano-measurer.software.informer.com). Figure 1 gives the size distribution and surface morphologies of raw powders. The shape of Co and NiCrAlY powder (22.0 wt% Cr, 10.1 wt% Al, Y 0.90 wt%, Ni Bal.) was spheroidal, and the TiC powder had an irregular shape. The average size of feedstock was 35.8 μm, 71.3 μm and 74.7 μm, respectively. The substrate of coatings was the AISI 304 stainless steel with the dimension of 45 mm×45 mm×5 mm. Before the experiment, the AISI 304 was roughen using sandpaper (Ra 3.2 μm), and then washed to remove the impurities in acetone in order to increase the adhesion between the coatings and the substrate. The component ratio of designed composite coatings is listed in Table 1, and the coatings without and with TiC are labeled as CT, CT6, CT8 and CT10 in the following tests. The composite powder was mixed evenly using a V-type mixer at a speed of 30 rpm for 3.0 h. Finally, the mixed powder of coatings was dried at 150 °C for 10 min, which ensured the high flowability of powders. The CO2 coaxial laser cladding system with a synchronous powder feeder (Shanxi Zhongmei Laser Technology Co., Ltd.) was employed to fabricate coatings over AISI 304 steel. The setting parameters of laser cladding are given in Table 2. The argon gas was chosen as the carrier gas and shielding gas. The tested surfaces of different specimens were polished to achieve a finish surface (Ra 0.1 μm) for the following tests.

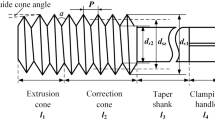

The sliding wear tests of different coatings were performed by a ball-on-disk wear tester in air (see Fig. 2). The lower disk was the prepared composite coatings, and the upper tribo-pair, with a hardness of 16.0 GPa and a diameter of 6.0 mm, was the commercially available Si3N4 ceramic ball which was widely used as bearing material in jet engine15. According to the ASTM G99 standard, the normal load and sliding speed were set at 10 N and 0.25 m/s. the test temperatures were 25 °C (room temperature), 200 °C, 400 °C, 600 °C and 800 °C. The computer automatically recorded the real-time friction curves of coatings, and a non-contact surface profiler (Micro XAM) was employed to obtain the wear volume (mm3) that was divided by the sliding distance (m) and the normal load (N) to calculate wear rates (mm3/N m). The each sliding test were performed four times at each test point to make the data more exact. In this study, the average wear rates and friction coefficients of coatings were given.

Schematic diagram of high-temperature tribometer (Created using SOLIDWORKS 2022 (https://www.solidworks.com)).

An X-ray diffractometer (DIFFRACTOMETER-6000) was employed to identify the phase of coatings and the oxides on wear tracks ranging from 20 to 100°. The HVS-1000Z Vickers-hardness tester was used to measure the hardness profile of cross section of coatings with a dwell duration of 15 s and a load of 300 g, and six measurements were repeated to reduce the error. The average value of six measurements was recorded as the hardness of prepared coatings. The elemental distribution, microstructure and wear morphologies of coatings were analyzed by a scanning electron microscope (SEM IT-300) equipped with an energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS Aztec X-MAX-50).

Results and discussion

Microstructure and hardness

The XRD spectrums of coatings without and with TiC are presented in Fig. 3. The different metal elements form alloying phases in the coatings. Because of the high solid solubility and affinity of Ni, Cr and Al elements in Co crystal, the NiCrAlY occurs decomposition so that these alloying elements react with Co element to generate the Ni-, Cr- and Al-rich γ-Co(fcc) solid solution under high temperature in the molten pool16,17. As the temperature decreases, the γ-Co(fcc) solid solution with high temperature stability does not have enough time to happen the martensitic transformation to generate ε-Co(hcp) with low temperature stability because of the feature of quick cooling of laser cladding17,18. Meanwhile, the alloying element Ni can provide a stabilizing effect for γ-Co(fcc) solid solution. And therefore, the γ-Co(fcc) solid solution is maintained in coatings, and the β-NiAl phase is precipitated firstly from the γ-Co(fcc) solid solution with the decreased temperature of molten pool19. However, the content of Y element is too low to detect the corresponding compounds from coatings. Thus, the solid solution reaction of Co and NiCrAlY leads to the formation of γ-Co(fcc) solid solution and β-NiAl intermetallic phase in coatings. Additionally, when the TiC is added into coatings, the diffraction peaks of TiC are found in XRD patterns. It is noteworthy that the intensity of diffraction peaks is gradually enhanced with the increase in TiC mass fraction, and no diffraction peak of new phase related to Ti and C elements is detected, meaning that the TiC has a high thermal stability during laser cladding. It is inferred that the phases of composite coatings with TiC consist of γ-Co(fcc), β-NiAl and TiC phases.

Figure 4 gives the BEI images of cross sections of coatings. The prepared coatings have a thickness of approximate 1.3 ± 0.05 mm, and no obvious defect presents in coatings such as crack and holes, indicating that the coatings keep a compacted microstructure. Specifically, a wave-shaped fusion line is noted at the interface between the substrate and the cladding zone. This is due to the fact that the substrate and metal powder are molten under the effect of laser beam20. The metal elements diffuse and occur alloying reactions at the interfaces to form a thin and alloying layer, resulting in a good metallurgical bonding between the coating and the substrate. The main element contents of cladding zone and substrate shows an obvious decrease trend in the bonding zone (see Fig. 4e). It means that that the prepared has not been diluted by substrate. It also indicates that the process parameters are conductive to fabricate dense composite coatings containing TiC.

Figure 5 gives the magnification images of CT and CT8 in the lower and upper regions of coatings. As seen from figures, some tiny holes are noted in coatings, the reason for which is that the volume change of powders of coatings in order to remain the void when the metal powders are molten. Additionally, the carrier gas and shielding gas are not enough time to escape from the cladding zone because of the rapid solidification of molten pool, and argon gas is sealed so as to form some tiny holes in cladding zone18,20. Compared with the microstructure of CT coating, the CT8 shows the different microstructure due to the introduction of TiC particle, including the white phase and the black phase. Combined with the EDS element mappings (see Fig. 5e) and XRD results, the white phase is defined as γ-Co(fcc) and β-NiAl, and the black phase is regarded as TiC. The TiC phase keeps a smaller size as compared with TiC powder, which may be related to the partially melted TiC particle because of the high energy of laser beam. The melted TiC phase solidifies again as the temperature of molten pool drops. However, the distribution of TiC of CT8 coating is differ from region to region, which indicates the directionality of grain growth of coatings. This can be explained by the solidification theory of laser cladding18,21, the development of microstructure of coatings is decided by the ratio of the solidification rate and the temperature gradient. The direction of hear flow influences the grain growth of coatings. In the lower region of coatings, the temperature gradient of molten pool is fairly high due to the low temperature of substrate, but the solidification rate is very low. The ratio is high in molten pool at the bottom of coatings. And therefore, the crystallization direction of compounds is perpendicular to the interface of coating/substrate, which leads to the distribution of TiC at the boundary of columnar crystal. With the movement of solid-liquid interface of molten pool to the coating top, the temperature gradient declines, whereas the solidification rate rises in order to increase the supercooling ahead of the molten pool. The grain growth is gradually affected by the heat flow in horizontal direction, so the formation of columnar crystal is restricted, leading to the formation of equiaxed crystal in coatings. The presence of equiaxed crystal would help to increase the hardness of coatings22.

The hardness distribution of prepared specimens along the depth is given in Fig. 6. The microhardness of all coatings shows a decrease trend at different distances from substrate. Generally, the distribution of hardness corresponds to the thickness of coatings, accompanied by a slight fluctuation, indicating that the coatings keep a dense and uniform structure. Furthermore, the coatings show a gradually declining variation of hardness from the cladding zone to the substrate. This is because that the bottom of coatings is diluted by the substrate at the interface of coating and substrate to some extent23. The coatings without and with TiC have higher hardness than AISI 304 steel, which is conducive to enhancing the wear resistance of coatings during wear. With the addition of TiC particle, the hardness of composite coatings is sharply increased from about 270 HV to 580 HV, and the hardness of coatings with TiC is about 2.7 times as high as that of AISI 304 steel. As for why the hardness of coatings is increased, one reason may be that the hard TiC phase dispersion can inhibit the dislocation movement in order to enhance the hardness of coatings. Hard TiC particle shows a dispersion strengthening mechanism24, and the strengthening effect is increasingly evident as the content of TiC rises. The other one is that the TiC particle with high melting point acts as a spontaneous nucleation site to make the grain growth easily so as to increase the amount of grain boundaries of coatings. And therefore, the hard phase dispersion shows a grain refinement strengthening effect. Meanwhile, the quick cooling speed of laser cladding also plays an important role in refining grain size to enhance the hardness of coatings18,22.

Wear performance

Figure 7 presents the real-time friction curves and friction coefficient with temperature of prepared coatings without and with TiC after tests at different temperatures. According to the real-time friction curves, all coatings keep relatively stable values of friction coefficients. Meanwhile, the values keep a downward trend firstly as the test temperature rises up to 600 °C, followed by a rise in friction coefficient at 800 °C. The coatings have the highest friction coefficients at low temperature, but they reach the minimum values at 600 °C. In addition, the friction coefficient of coatings with TiC is higher than that of coating without TiC at all test temperatures. Most importantly, the friction coefficients gradually increase with the increase of TiC content. The 10.0 wt% TiC reinforced composite coating displays the highest friction coefficients. It means that the introduction of TiC deteriorates the friction reduction of composite coatings. The wear profiles and average wear rate of specimens under different temperatures at 10 N and 0.25 m/s are given in Fig. 8. The wear rates of coatings are in the magnitude of 10− 5 mm3/Nm. The wear rates decline firstly when the temperature reaches up to 400 °C and the laser clad coatings obtain the lowest wear rates at 400 °C. However, the wear rates increased at 600 °C and 800 °C. The coatings with TiC possess low wear rate in comparison with the coating without TiC, suggesting that the TiC can remarkably increase the wear resistance of coatings24. Moreover, the values of wear rate of reinforced coatings decline firstly, and then increase with increasing TiC content at test temperature range. Take into consideration of the values of friction and wear of coatings, 8.0 wt% TiC is the optimal content for the composite coatings. Thus, the CT8 coating has the desirable tribological performance from 25 to 800 °C. The wear mechanisms of specimens will be discussed below.

Accordingly, the test temperature, TiC and its content have notable impact on the wear behavior of coatings at 25–800 °C. At low temperature, the coating surfaces maintain a high level of strength that can fix the hard TiC phase dispersion on the sliding surfaces during wear. As the wear occurs, the soft phase is firstly removed from the sliding surfaces, resulting in the protrusion of TiC particles on the sliding surfaces. The hard TiC dispersion scrapes the sliding surfaces of tribo-pair to increase the anti-shearing force of relative sliding. Meanwhile, the asperities of counterparts can collide each other or crush during sliding. Additionally, according to the semi-empirical Archard’s law13,25, the higher hardness can provide a higher wear resistance for materials. Due to the strengthening effects of TiC, the coatings with TiC have a high hardness. And therefore, the coatings show relatively high wear resistance and friction coefficient at low temperature. On the one hand, the ductility and toughness of coatings are improved because the thermal softening is induced by the frictional heat and test temperature when the temperature is further elevated to 400 °C26. The improvement of toughness of coatings can result in the increase of deformability of coatings surfaces that can absorb more frictional energy thereby suppressing the initiation and propagation of cracks around TiC particles on worn surfaces. The hardness and toughness reach a reasonable balance in order to further improve the wear resistance. On the other hand, owing to the high temperature, the alloying element occurs complicatedly tribo-chemical reactions to generate oxides with low shearing strength (see Fig. 9)27. These soft oxides are compacted to from a dense tribo-layer on the wear tracks to reduce the contact of asperities of tribo-pairs (see Fig. 10a), which greatly improve the self-lubrication and wear resistance of coatings below 400 °C18,20. At 600 °C, the phenomenon of thermal softening and the tribo-chemical reactions are enhanced. The decreased hardness of coatings degrades the wear resistance due to the elevated temperature therefore increasing the wear rate. However, the increased content of oxides can provide obvious lubricating effect for the coatings to keep lower friction coefficients.

As the temperature reaches up to 800 °C, the tribo-chemical reactions are accelerated to produce different kinds of oxides over the sliding surfaces (see Fig. 9). These oxides from a thicker tribo-layer on the wear track (see Fig. 10b), which can further improve the high-temperature self-lubrication of coatings at 800 °C. Nevertheless, the strength and hardness of coatings continuously decline because of the elevated temperature, which weakens the supporting ability of coating matrix for hard TiC phase dispersion. A large amount of TiC particle falls off from the contact surfaces, which is embed in the tribo-layer. This phenomenon destroys the friction reduction of coatings with TiC. The β-NiAl phase is easily oxidized to produce Al2O3 simultaneously as an aluminum reservoir on the wear tracks at elevated temperature19. It is confirmed by the strong diffraction peaks of Al2O3 according to the XRD result of wear track (see Fig. 9), and Ti, Al, C, etc. element mappings of tribo-layer (see Fig. 10c). With increasing TiC content in coatings, the more TiC particles present on the wear tracks. Additionally, TiC and Al react with other oxides to generate Al4O4C hard phase on the wear tracks. The TiC, Al4O4C and Al2O3 hard phases form a third-body wear process that offsets the partial lubricating effect of tribo-layer14, which is attributed to the high friction and wear of the coatings with TiC at high temperature. The wear mechanism can be illustrated by the wear model (see Fig. 11). For CT coating, the low hardness and lubricating effect of tribo-layer result in low friction coefficient and high wear rate. The CT8 coating has a satisfactory tribological performance due to the moderate hardness and TiC content from 25 to 800 °C as compared with traditional high-temperature alloy28. It is inferred that the composite coating is a potential wear resistant coating for moving parts.

Schematic illustrations of the wear process and mechanism of coatings with rise in test temperature (Created using SOLIDWORKS 2022 (https://www.solidworks.com)).

Analysis of wear tracks

The wear tracks of coatings without and with TiC after sliding are given in Fig. 12 at room temperature. As observed, for CT coating, the γ-Co(fcc) solid solution possesses good ductility that can promote the formation of some cold-welding points of asperities of tribo-pairs under the normal load at room temperature29. The adhesive points happen plastic deformation until they fracture on the wear track of CT under the effect of cyclic stress, and the spalling material turns into the wear debris which is compacted by the sliding balls to become large patch on the wear tracks. Thus, the severe plastic deformation, patch and a small amount of wear debris are presented on the wear track of CT coating (see Fig. 12a). The dominant wear mechanism of CT coating is the primarily adhesive wear and plastic deformation that account for the high wear rate at room temperature. Compared with CT coating, the coatings with TiC have relative smooth wear surfaces (see Fig. 12b, c and d), the reason for which is that the introduction of TiC enhances the brittleness and hardness, leading to a decrease in the plastic deformation degree22,31. Meanwhile, the TiC phase can effectively support the normal load. Meanwhile, the peeling TiC particle from the wear tracks becomes the wear debris under the action of reciprocating force, which is confirmed by EDS analysis (see Fig. 12e). The amount of wear debris containing TiC increases with increasing TiC content on the wear tracks, which plows the coating surfaces in order to increase the material loss of coatings. Accordingly, the worn surfaces present the sign of wear debris and grooves. This suggests that the wear mechanisms of coatings with TiC is abrasive wear and slightly plastic deformation. It also corresponds to the high friction coefficient and wear rate with increasing TiC content.

Figure 13 shows the wear tracks morphologies of different coaitngs at 400 °C. It is clear that the wear tracks are relativly smooth at 400 °C in comparison with those of coatings at room temperature. Due to the significant increase in the content of oxides at 400 °C, these oxides are compacted to form a visible tribo-layer on the wear tracks, which reduce the real conact area of tribo-pairs in order to enhance the self-lubrciating property of coatings. There is an obvious plastic deformation phenomenon on the wear track of CT. The plastic deformaiton of matrix does not help to form the intact tribo-layer29,31. And therefore, the coating without TiC presents an incomplete tribo-layer. It suggestes that the wear mechanism of CT coaitng is mianly plastic deformation and oxidative wear. The coatings with TiC maintain the intact tribo-layer regarding of the high strength upon the strengtening effect of TiC phase disperson. And therefore, the coaitngs with TiC have better wear resistance as compared with coaitng without TiC. However, the spalling TiC particles still scrape the contact surfaces to cause obvious grooves, which elevate the fricion coefficients of coatings. Besides, the amount of wear debris containing TiC gradually increases on the wear trcaks, leading to an increase in friction coefficient with increasing TiC content. Becasue the moderate ductily of coatings can hinder the propagation of cracks around TiC particles due to the thermal softening29,32, the spalling trend of TiC of coatings with TiC is reduced at 400 °C. Nevertheless, the excessive TiC leads to the spallation of more hard wear debris that causes the more grooves on the worn surfaces of coatings. Thus, although the CT10 have the highest hardness, it shows the high wear rate as compared with other speciemns. It is deduced that the wear mechaniam of coatings with TiC at 400 °C is abrasive wear, plastic deformation and oxidative wear.

The morphologies of wear tracks of composite coatings after sliding at 800 °C are illustrated in Fig. 14. The wear tracks of coatings are coarser at 800 °C, which correspond to the high wear rates of prepared coatings. At elevated temperature, the wear tracks are covered with a distinct tribo-layer because the oxidation process is greatly promoted. As observed, some cracks are present on the tribo-layer, which is related to the continuous decrease in hardness of coatings. The soft coating surface can not support an intact tribo-layer31,33. The breakdown of the tribo-layer results in the exposure of coating to sliding surfaces and causes simultaneous wear and oxidation of coating, and then the tribo-layer is removed out from the wear tracks again during sliding. This cyclic process leads to the high wear rate of CT at 800 °C. The oxidative wear is the dominant wear mechanism of CT at 800 °C. In contrast, for the coatings with TiC, the tribo-layer is relativly intact and dense owing to their high harness, which attributes to low wear rates as compared with CT coating. However, the TiC particle easily detaches from softer coatings due to the repeated deformation of sliding surfaces, accumulating on the sliding surfaces (see Fig. 13e). Furthermore, the amount of TiC particle on the worn surfaces gradually rises with increasing TiC content in the coatings. The TiC and β-NiAl phase react to generate Al4O4C and Al2O3 hard phases due to the tribo-chemical reactions, respectively. These hard phases scrapte and plow the tribo-layer, resulting in the breakdown of the integrality of tribo-layer and the increase in sliding resistance at 800 °C18,33. As a result, the lubricating effect of tribo-layer is weakened. The coatings suffer from direct wear and oxidation during sliding wear at elevated tempertue, which increase the fricion and wear of coatings with TiC at 800 °C. At 800 °C, the wear mechanisms of composite coatings with TiC are characterized by the oxidative wear, accompanied by the abrasive wear.

SEM images of wear surfaces of Si3N4 ball as tribo-pair sliding against CT8 coating at varied temperatures are illustrated in Fig. 15. The contact area of counterpart firstly is decreased, and then increased with temperature, and this change is consistent with that of wear rates of composite coatings at room temperature -800 °C. The amount of transfer material on the counterpart increases as the temperature rises to 800 °C. This transfer material is transferred from the sliding surfaces of coating to counterpart, which is regarded as the surface material and oxides developed on the wear tracks (see Fig. 15d). It is mainly ascribed to the adhesion of material occurring simultaneously and the evident increase of oxides on the wear tracks with the increase in test temperatures to 800 °C during wear. The compacted transfer material tightly adheres to the sliding surfaces of counterpart to form a dense transferred layer. The wear of coatings is converted from ball-on-coating to transferred layer-on-tribo-layer with increasing temperature, which reduces the direct contact of asperities and the real contact area of counterparts therefore effectively improving the self-lubricating property of coatings at elevated temperature29,34.

Conclusions

-

(1)

The wear resistant Co-20 wt% NiCrAlY-(6.0, 8.0 and 10.0 wt%) TiC coatings were fabricated by laser cladding technology. The NiCrAlY decomposed and formed compounds. The phase compositions of coatings consisted of γ-Co(fcc), β-NiAl and TiC phases. The Vickers-hardness composite coatings was increased from about 270 HV to 580 HV with the introduction of TiC.

-

(2)

The friction coefficient and wear resistance of coatings with TiC were higher than those of coating without TiC at room temperature-800 oC. The friction coefficients gradually increased owing to the frictional effect of TiC, in-situ synthetized Al4O4C and Al2O3 ceramic particles from room temperature to 800 oC. The wear rates of coatings are in the magnitude of 10− 5 mm3/Nm, and the wear rates reached the minimum value at 400 oC owing to the balance of hardness and toughness. When temperature continued to rise, the wear rates increased because the TiC, Al4O4C and Al2O3 destroyed the lubricating effect of tribo-layer. The coating with 10 wt% TiC kept the worst tribological behavior due to the high content TiC, Al4O4C and Al2O3. In general, Co-20 wt% NiCrAlY-8.0 wt% TiC showed a satisfactory tribological properties, which was attributed to the moderate hardness and in-situ synthetized solid lubricant, as well as the intact tribo-layer. The prepared coatings were potential candidate as protective coating for hot-end parts at room temperature to 800 oC.

-

(3)

At low temperature, the coatings with TiC showed the slight plastic deformation and abrasive wear; as the test temperature reached up to 400 oC, the wear mechanism was the plastic deformation, abrasive wear and oxidative wear; at 800 oC, the wear mechanism was the oxidative wear, accompanied by the abrasive wear.

Data availability

All experimental data are included in this paper, and other datasets or analyzed in this study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shirani, A., Li, Y. Z., Eryilmaz, O. L. & Berman, D. Tribocatalytically–activated formation of protective friction and wear reducing carbon coatings from alkane environment. Sci. Rep. 11, 20643 (2021).

Qu, C. C., He, B., Cheng, X. & Wang, H. M. Microstructure and wear characteristics of laser-clad Ni-based self-lubricating coating incorporating MoS2/Ag for use in high temperature. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 33, 4481–4492 (2024).

Cui, G. J. et al. Nano-TiO2 reinforced CoCr Ma wear resistant composites and high-temperature tribological behaviors under unlubricated condition. Sci. Rep. 10, 6816 (2020).

El-Kady, O. A. M. Effect of nano-yttria addition on the properties of WC/Co composites. Mater. Des. 52, 481–486 (2013).

Anjani, K. & Kumar, A. D. Evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties of Co-SiC tungsten inert gas cladded coating on 304 stainless steel. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 24, 591–604 (2021).

Chen, W. et al. Research on high-temperature friction and wear performances of stellite 12 laser cladding layer against coated Boron steels. Wear 520–521, 204665 (2023).

Xu, P., Lin, C. X., Zhou, C. Y. & Yi, X. P. Wear and corrosion resistance of laser cladding AISI 304 stainless steel/Al2O3 composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 238, 9–14 (2014).

Alhattab, A. A. M., Dilawary, S. A. A., Motallebzadeh, A., Arisoy, C. F. & Cimenoglu, H. Room and high temperature sliding wear characteristics of laser surface melted stellite 6 and Mo-alloyed stellite 6 hardfacings. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 30, 302–311 (2021).

Khoddamzadeh, A., Liu, R., Liang, M. & Yang, Q. Wear resistant carbon fiber reinforced stellite alloy composites. Mater. Des. 56, 487–494 (2014).

Öge, M. et al. Effect of boriding on high temperature tribological behavior of CoCrMo alloy. Tribol Int. 187, 108697 (2023).

Zhou, J. L. et al. Enhancement of high-entropy alloy coatings with multi-scale tic ceramic particles via high-speed laser cladding: Microstructure, wear and corrosion. Appl. Surf. Sci. 685, 162061 (2025).

Martínez-Hernández, A. et al. Effect of heat treatment on the hardness and wear resistance of electrodeposited Co-B alloy coatings. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 8, 960–968 (2019).

Encalada, I. A. et al. Wear behavior of HVOF sprayed cobalt-based composite coatings reinforced with Cr3C2. Wear 546–547, 205310 (2024).

Jiang, D. et al. Wear and corrosion properties of B4C-added CoCrNiMo high-entropy alloy coatings with in-situ coherent ceramic. Mater. Des. 210, 11006 (2021).

Mitchell, D. J., Mecholsky, J. J. & &Adair, J. H. All-steel and Si3N4-steel hybrid rolling contact fatigue under contaminated conditions. Wear 239 (2), 176–188 (2000).

Ni, J. H., Wen, M., Jayalakshmi, S., Geng, Y. F. & Chen, X. Z. Investigation on microstructure, wear and friction properties of CoCrFeNiMox high-entropy alloy coatings deposited by powder plasma Arc cladding. Mater. Today Commun. 39, 108807 (2024).

Xia, Z. X. et al. Substructure formation mechanism and high temperature performance in conicraly seal coating by laser melting deposition with inside-laser coaxial powder feeding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 367, 108–117 (2019).

Cui, G. J., Han, W. P., Zhang, W. C., Li, J. X. & Kou, Z. M. Friction and wear performance of laser clad mo modified stellite 12 matrix coatings at elevated temperature. Tribol Int. 196, 109738 (2024).

Karaoglanli, C. A., Ozgurluk, Y. & Doleker, M. K. Comparison of microstructure and oxidation behavior of conicraly coatings produced by APS, SSAPS, D-gun, HVOF and CGDS techniques. Vacuum 180, 109609 (2020).

Liu, Y. F. et al. Microstructure evolution and high-temperature tribological behavior of Ti3SiC2 reinforced Ni60 composite coatings on 304 stainless steel by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 420, 127335 (2021).

Deng, C., Yi, Y. L., Jiang, M. L., Hu, L. X. & Zhou, S. F. Microstructure and high-temperature resistance of Al2O3/CoNiCrAlY coatings by laser cladding. Ceram. Int. 49, 32885–32895 (2023).

Wang, X. M., Ren, X. C., Xue, Y. P. & Luan, B. L. Investigation on microstructure and high-temperature wear properties of high-speed laser cladding inconel 625 alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 30, 626–639 (2024).

Guo, C. et al. High temperature wear resistance of laser cladding NiCrBSi and NiCrBSi/WC-Ni composite coatings. Wear 270, 492–498 (2011).

Wu, C. L. et al. Laser surface alloying of fecocralniti high entropy alloy composite coatings reinforced with tic on 304 stainless steel to enhance wear behavior. Ceram. Int. 48, 20690–20698 (2022).

Archard, J. F. Contact and rubbing of flat surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 24, 981–988 (1953).

Adarsha, H., Ramesh, C., Nair, N., Karisiddeshwaraswamy, K. & Chaturvedi, A. Investigations on the Abrasive Wear Behaviour of Molybdenum Coating on SS304 and A36 using HVOF Technique. Mater. Today: Proc. 5, 25667–25676 (2018).

Dimitrov, V. & Komatsu, T. Classification of simple oxides: A polarizability approach. J. Solid State Chem. 163, 100–112 (2002).

Cui, G. J. et al. Dry-sliding wear characteristics of laser clad mo matrix alloy coatings over a wide range of temperature. Tribol Int. 196, 109671 (2024).

Yu, T. & Tang, H. Y. Microstructure and high-temperature wear behavior of laser clad TaC-reinforced Ni-Al-Cr coating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 592, 153263 (2022).

Zhu, Y. Q. et al. Study on the friction and wear performance of laser cladding WC-TiC/Ni60 coating on the working face of shield bobbing cutter. Opt. Mater. 148, 114875 (2024).

Soleimani, F., Adeli, M., Soltanieh, M., Saghafian, H. & Karimi, A. Fabrication and wear behavior of TiC/TiB2-reinforced NiAl intermetallic matrix composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 30, 5770–5784 (2024).

Sun, X. F. et al. Enhancing the wear and high-temperature oxidation behavior of NiCrBSi coatings by collaboratively adding WC and Cr3C2. Surf. Coat. Technol.. 473, 129968 (2023).

Cho, Y. T. et al. Surface properties and tensile bond strength of HVOF thermal spray coatings of WC-Co powder onto the surface of 420J2 steel and the bond coats of Ni, NiCr, and Ni/NiCr. Surf. Coat. Technol. 203, 3250–3253 (2009).

Wang, X. W. et al. High temperature friction and wear behavior of Mo–Si–B/ZrB2 composites. Tribol Int. 196, 109694 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (Grant No. 202303021211163), the Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (Grant No. 2021-060) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51775365, U1910212).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haotian Cui and Gongjun Cui wrote the manuscript. Rongqian Yang prepared the samples and tested the tribological properties. Xun Li analyzed the data. Junxia Li and Ziming Kou reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, H., Yang, R., Cui, G. et al. Design and enhanced high temperature wear performance of laser clad Co matrix coatings containing NiCrAlY and TiC over a wide temperature. Sci Rep 15, 7984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92694-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92694-2