Abstract

A global experience that every human life meets is death. For several decades, individuals have reported their unique encounters with near-death experience (NDE), which has raised many unanswered questions. In the present experiment, we utilize continuous local field potential (LFP) during the euthanasia process to show the dynamic changes of frequency band power in four distinct regions of the rat brain from intracranially implanted electrodes: the right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), right thalamus (Po), left trigeminal ganglion (TG), and the right primary visual cortex (V1M). At the end of a separate migraine study, two groups of rats underwent the euthanasia process: freely-moving and anesthetized. The findings from the current study indicate that (1) in the freely-moving group, a rebound spike in LFP was observed in all five frequency bands 3-minutes after CO2 initiation, followed by a general decrease of power; (2) in the anesthetized group, a general decrease of power in all five frequency bands was observed during the CO2 euthanasia, with less rebound activities; (3) high correlation among these five frequency band powers from the four designated brain regions were observed. The rebound surge observed in the freely-moving group may help us understand the NDE phenomenon. Perhaps the profound experiences reported at the end of life emerge during the brain’s final surges of activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After surviving a life-threatening crisis, many individuals report encountering near-death experience (NDE). The phenomenon of NDE has long been of interest. The earliest medical report made regarding NDE was by a French military physician, Pierre-Jean du Monchaux, in 1740. After a phlebotomy which left Monchaux unconscious for a long period of time, Monchaux described seeing “pure and extreme light that he thought he was in Heaven,”1. Similarly, in 344 cardiac patients who were successfully resuscitated post-cardiac arrest, NDE showed prevalence in 18% of patients2. Near-death studies explain this experience as a transcendental, out-of-body experience of consciousness traveling to a different “dimension”3. In accounts of climbers surviving near-death falls, the emotions reported consisted of clarity, calm solemnity, and acceptance. These survivors recalled time slowing down and becoming lengthened4. Though many reported NDEs have been positive, there have also been reports of unpleasant NDEs called negative near-death experiences. These experiences are characterized by a dark void and judgment, dominated by fear5.

There are various findings as to what happens to the electroencephalography (EEG) frequency bands at various levels during NDE6,7. In one study conducted8, with the use of the hypnosis-based protocol, it was revealed by electroencephalography (EEG) findings that the recall of NDE memories was associated with delta oscillations. Delta power was explained as representing hallucinations and memories of the past. Additionally, theta oscillations were also associated with NDE memories. Theta power was explained as representing episodic memory in EEG recordings. Interestingly, this study revealed no association with gamma power, which represents accurate memories that have occurred in the physical world. These findings indicate that NDE memories are “episodic memories of events experienced in a peculiar state of consciousness,”8. On the contrary, in a separate study conducted by the Borjigin lab9, findings reveal immense coherent gamma oscillations during cardiac arrest in rats. Additionally, in a retrospective study, the Borjigin lab further investigated whether the surge of gamma oscillations was also present in humans through the use of four comatose dying patients before and after ventilatory support10. Electroencephalogram and electrocardiogram signals reveal a surge of gamma power stimulated by global hypoxia in two patients, and further surged as the cardiac conditions declined. This present study confirms the previous findings in animal models and is further confirmed in a separate study where an 87-year-old patient suddenly underwent cardiac arrest while on EEG. The suppression of bilateral hemispheric responses revealed a rise of absolute power in gamma activity whilst having a reduction in theta power. Additionally, a decrease in delta, beta, alpha, and gamma power was revealed post-cardiac arrest, although relative gamma power was shown to have a higher percentage in comparison to the interval between seizures11. In a different study using hypnotic modulation and EEG, the findings reveal that the recollection of NDE memories showed a rise in alpha activity in the frontal and posterior areas of the brain12. Moreover, in a study conducted by Beauregard and colleagues13, during a meditative state, brain activity was measured in NDE using EEG and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The findings from this study reveal neuroelectric changes in various brain regions, such as the temporal lobe and the visual system. End-of-life electrical surges (ELES) have been theorized to be the driving force behind NDEs14,15. Most recently, in patients undergoing CPR while connected to EEG monitoring, it was revealed that cognitive activity emerged, and so did the brain’s electrical activity. This emergence of spikes was similar to the same activity seen while performing common tasks such as talking, only this time, the patients were undergoing resuscitation for up to an hour. This study reaffirms the belief of consciousness, even during the obvious detectable external signs showing otherwise16. Furthermore, in a different study, researchers found a slow, large, late wave in EEG results after the decapitation of rats, perhaps showing the time between life and death17. Decapitation studies are useful in helping us further examine EEG changes18.

The hypothesis is that the neuronal activity during the euthanasia process will decrease gradually as reflected by a decrease in power of all frequency band power activity. We explored the LFP changes from intracranially implanted electrodes at the end of another experiment when animals were euthanized19. The four areas of interest are the right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), right thalamus (Po), left trigeminal ganglion (TG), and the right primary visual cortex (V1M), as chosen from the previous separate study. The LFP can be subdivided into 5 frequency bands of delta (0.1–3 Hz), theta (3–7 Hz), alpha (7–12 Hz), beta (12–30 Hz), and gamma (30–100 Hz), respectively. LFP has been used by our lab routinely to study the neural mechanisms of pain processing20,21,22. A section of this data has been reported at the Society for Neuroscience23.

Results

Representative LFP traces showed a decrease in brain signals during euthanasia process

Two representative LFP traces demonstrated a gradual dying process after CO2 was initiated in the euthanasia chamber (Fig. 1). The left column showed LFP from one rat that was not under long-term isoflurane anesthesia, whereas the right column was. In each sub-section (e.g., A for ACC), the upper trace showed the raw LFP signals collected by our recording electrode, and the lower part was the converted time-frequency power spectrum indicating the intensity of power at each time point (x-axis) and each frequency band (y-axis). The power intensity is represented from low (blue) to high (red). The first 5 min (300s) was the baseline activity while the animal was alive; at 300s, CO2 was turned on, and a decrease in activity was observed (about 400s). In the freely-moving animal (left column), a rebound signal can be observed at 420–500 s; while not so obvious in the anesthetized animal group (right column). On the top of the figure, a 5s-expanded trace was extracted from the baseline, after CO2, rebound, and a dead period. A discernibly different pattern of activity can be observed.

Representative time-frequency spectrogram of raw trace waveform (top, Ampl. In mV) and LFP power (bottom) of freely-moving (left column) and anesthetized animals (right column) during euthanasia in the (A) right ACC, (B) right Po, (C) left TG, and (D) right V1M, respectively. The y-axis represents the frequency power intensity (bottom, red for higher power, maximum at 56dB), and the x-axis represents time (s). The blue arrow is the start of CO2 at 300s (5 min), and the red arrow indicates a rebound activity around 7–8 min. An expansion of different time segments (5s) for ACC freely-moving traces are shown above to represent the following status: alive (160–165 s), early euthanasia after CO2 (360–365 s), rebound (440–445 s), and dead (1500–1505 s).

Decrease of power during the euthanasia process, 8-minute rebound surge revealed

A total of 39 rats (n = 18 in the freely-moving group; and n = 21 in the anesthetized group) were used to obtain the mean power for delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands. To represent a clear dynamic change of power during the euthanasia process, data were analyzed every 10s. It was found that both the 10s raw and normalized power showed a decrease during the euthanasia process (Fig. 2), in all frequency bands in the four recorded brain regions (right ACC, right Po, left TG, right V1M). The decrease was slower in the freely-moving group than in the anesthetized group, and an obvious rebound was also more obvious at 7–8 min in the freely-moving group.

To further perform statistical analysis, the 10s data were merged to obtain the mean of 1-minute (Fig. 3). In the 1-minute raw and normalized power spectrum analysis, a decrease in power during the euthanasia process was also revealed. In the freely-moving group, from 7 to 35 min, the power in all five frequency bands was significantly lower than in the first minute. Interestingly, a rebound surge was revealed at the 8-minute mark in comparison to the 7-minute time point when brain activity showed a falling phase by CO2. In the anesthetized group, a general decrease of power in all five frequency bands was revealed approximately two minutes after CO2 initiation in all four brain regions (right ACC, right Po, left TG, right V1M), and a significant LFP drop was found between times 7–35 (Fig. 3).

1-minute raw and normalized power spectrum analysis for the (A) right ACC, (B) right Po, (C) left TG, and (D) right V1M, respectively. The y-axis represents the LFP raw or normalized power ratio, while the x-axis represents time. “*” – significant from the 1st min; “†” – significant between 8th and 7th min; dashed area – significance between two groups. Grey coloring represents the anesthetized group, and colored markings represent the freely-moving group. ‘*’ indicates p < .05, ‘**’ indicates p < .01, ‘***’ indicates p < .001, and is the same for ‘†’ symbol.

Summary of statistical analysis results

Significant differences found in frequency bands of LFP activity in the ACC region

The results from the raw data using a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing demonstrated that there was a main effect of groups at the beta band (F(1,37) = 7.176, p = .011, ηp2 = 0.162) and gamma band (F(1,37) = 20.000, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.351), but no main effect of groups at the delta band (F(1,37) = 0.047, p = .830, ηp2 = 0.001), theta band (F(1,37) = 0.014, p = .906, ηp2 < 0.001) or alpha band (F(1,37) = 0.224, p = .639, ηp2 = 0.006). These results suggest that there are significant differences in the ACC LFP power between the freely-moving group and the anesthetized group at the beta and gamma band, but no significant difference at the delta, theta, or alpha bands (Table 1). A more detailed summary of means and SEMs is shown in Supplementary Table 1 (same for the following sections).

The results from the normalized data using a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing demonstrated that there was a main effect of groups at the theta band (F(1,37) = 5.539, p = .024, ηp2 = 0.130), alpha band (F(1,37) = 4.680, p = .037, ηp2 = 0.112), and gamma band (F(1,37) = 11.670, p = .002, ηp2 = 0.240, but no main effect of groups at the delta band (F(1,37) = 3.546, p = .068, ηp2 = 0.087) or beta band (F(1,37) = 0.074, p = .788, ηp2 = 0.002). These results suggest that there are significant differences in the ACC LFP power between the freely-moving group and the anesthetized group in all frequency bands except for the delta and beta bands (Table 1).

Significant differences found in frequency bands of LFP activity in the Po region

The results from the raw data using a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing demonstrated that there was a main effect of groups at the delta band (F(1,37) = 6.632, p = .014, ηp2 = 0.156), theta band (F(1,37) = 17.341, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.325), alpha band (F(1,37) = 22.597, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.386), beta band (F(1,37) = 20.811, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.366), and gamma band (F(1,37) = 31.554, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.467), suggesting that there are significant differences in the Po LFP power between the freely-moving group and the anesthetized group in all frequency bands (Table 1).

The results from the normalized data using a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing demonstrated that there was a main effect of groups at the gamma band (F(1,37) = 70.887, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.657), but no main effect of groups at the delta band (F(1,37) = 3.696, p = .062, ηp2 = 0.091), theta band (F(1,37) = 0.316, p = .578, ηp2 = 0.008), alpha band (F(1,37) = 1.195, p = .281, ηp2 = 0.031), or beta band (F(1,37) = 0.007, p = .935, ηp2 < 0.001), suggesting that there are significant differences in the Po LFP power between the freely-moving group and the anesthetized group at only the gamma band (Table 1).

Significant differences found in frequency bands of LFP activity in the TG region

The results from the raw data using a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing demonstrated that there was no main effect of groups at the delta band (F(1,37) = 0.343, p = .562, ηp2 = 0.009), theta band (F(1,37) = 0.659, p = .422, ηp2 = 0.018), alpha band (F(1,37) = 1.261, p = .269, ηp2 = 0.034), beta band (F(1,37) = 0.080, p = .779, ηp2 = 0.002), or gamma band (F(1,37) = 2.749, p = .106, ηp2 = 0.071). These results suggest that there are no significant differences in the TG LFP power between the freely-moving group and the anesthetized group in all frequency bands (Table 1).

The results from the normalized data using a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing demonstrated that there was a main effect of groups only at the theta band (F(1,37) = 4.968, p = .032, ηp2 = 0.118), but no main effect of groups at the delta band (F(1,37) = 0.307, p = .583, ηp2 = 0.008), alpha band (F(1,37) = 1.902, p = .176, ηp2 = 0.049), beta band (F(1,37( = 1.521, p = .225, ηp2 = 0.039), or gamma band (F(1,37) = 3.873, p = .057, ηp2 = 0.095), suggesting that there are significant differences in the TG LFP power between the freely-moving group and the anesthetized group at only the theta band (Table 1).

Significant differences found in frequency bands of LFP activity in the V1M region

The results from the raw data using a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing demonstrated that there was a main effect of groups at the delta band (F(1,37) = 4.176, p = .048, ηp2 = 0.101), theta band (F(1,37) = 50.262, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.576), alpha band (F(1,37) = 62.845, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.629), beta band (F(1,37) = 56.993, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.606), and gamma band (F(1,37) = 30.881, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.455), suggesting that there are significant differences in the V1M LFP power between the freely-moving group and the anesthetized group in all frequency bands (Table 1).

The results from the normalized data using a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing demonstrated that there was a main effect of groups at the theta band (F(1,37) = 8.824, p = .005, ηp2 = 0.197), alpha band (F(1,37) = 10.520, p = .003, ηp2 = 0.226), and gamma band (F(1,37) = 84.828, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.702), but no main effect of groups at the delta band (F(1,37) = 0.433, p = .515, ηp2 = 0.012) or beta band (F(1,37) = 1.380, p = .248, ηp2 = 0.037), suggesting that there are significant differences in the V1M LFP power between the freely-moving group and the anesthetized group in all frequency bands except for the delta and beta bands (Table 1).

Significant differences found in correlation coefficient among these five frequency bands from these four brain regions

To understand if one frequency oscillation from one brain area is correlated with another frequency oscillation, either within the same brain area or among the other three areas, a correlation analysis was conducted. A summary of the correlation coefficient values is shown in Fig. 4. There is an obvious high correlation among the five frequency band powers in the four brain areas, a reflection of the dying brain synchronizing their activities.

Correlation indices from four groups: Freely-moving raw (A. 0.6860–1.000), Freely-moving normalized (B. 0.7782–1.000), Anesthetized raw (C. 0.6864–1.000), and Anesthetized normalized (D. 0.6986–1.000). Correlation indices are calculated from mean values of the 1-minute data from four brain areas (ACC, PO, TG, and V1M) and five frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma).

Discussion

The current study concludes that there is a major difference between the freely-moving and anesthetized group patterns. More specifically, in the freely-moving group, the power is significantly lower from the 7 to 35-minute mark in comparison to the first minute, which indicates the death of the animal. Furthermore, our findings reveal a rebound LFP spike at 8-minutes total recording time, 3-minutes after CO2 initiation. These results suggest the possibility that it takes longer to euthanize a rat that was not previously under the influence of isoflurane on the same day. We believe the confounds of the previous application of NTG would have little effect on the euthanasia process: a process in which neurons die around the 5-minute mark. In both groups, euthanasia was induced 4.5 h after NTG was injected into the animal. The only difference was that one group of animals underwent 4.5 h of isoflurane anesthesia, and another group was awake, while NTG was given in both groups and recorded LFP for 4.5 h before the start of the euthanasia process. Similar to Borjigin’s findings9, instead of the cardiac arrest model, our CO2 euthanasia showed a similar pattern of decrease of all frequency band powers. However, we did not observe obvious high gamma band changes (data not shown; our frequency was up to 1500 Hz). That difference might be caused by Borjigin’s use of intracardial injection of KCl which would spread to the brain through the circulatory system. In a separate study, an overdose of chloral hydrate (CH) created a surge of high-frequency oscillations in the hippocampus of rats, pointing to the idea that this surge is not just limited to those who undergo cardiac arrest7,24. Interestingly, we also found a similar surge of brain activity in our rat model as being found in human studies14. Together, it may be inferred that when an individual has prolonged illness and unconsciousness, they are less likely to have a rebound peak in comparison to a healthy individual who suffered an unexpected accident and is undergoing the death phase. These individuals may have a higher rebound peak than the prolonged ill individual. This could suggest that the healthy individual is at the end of life, therefore efforts for resuscitation could prove to be useful whilst encountering this spike. However, it is still uncertain as to why only some patients experience ELES and not all25.

The reason behind NDE occurrence and its mechanism remains a mystery ladened with hypotheses and theories. Originating from Dr. Susan Blackmore, the “dying brain hypothesis” is perhaps the most prominent physiological justification26. This hypothesis affirms that the hallucinations experienced during NDE are generated by different physiological factors such as carbon dioxide acceleration27,28, hypercarbia, and oxygen deprivation such as hypoxia and anoxia28,29,30,31. Moreover, it is believed that anoxia might only play a certain role in NDE and is not entirely responsible for NDE itself26,32,33. This claim is supported by NDEs occurring in individuals who simply think they are going to die, in other words, occurring when there is no anoxia involved. Instead of NDE being a consequence of anoxia, the argument is that the emphasis should be focused on disinhibition of the brain instead of the anoxia itself. Blackmore further explains that the reason why individuals report seeing a tunnel and light during NDE is due to the cortical disinhibition connected with anoxia32,34.

One possible link behind NDE is REM sleep intrusion. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep was first discovered by Aserinsky and Kleitman in 1953, and one particular characteristic noted was that 20 out of 27 participants during REM sleep reported having detailed dreams35. In a study conducted by Kondziella and colleagues36, it was revealed that NDEs were reported in 10% of the participants, and, moreover, NDEs were more likely to be demonstrated in participants who had REM intrusion versus those who did not. Although there was a significant association found with REM sleep intrusion, various other factors such as age, gender, place of residence, etc., were not found to be associated with the quantity of NDE occurrence.

As previously mentioned, many individuals with NDEs have reported the perception of pure and extreme lights during their experience. One study explains that these pure and extreme lights during NDE could perhaps be due to the brief intensification of bioluminescent biophotons. Furthermore, the authors explain that the visual imagery experienced during NDEs could be linked to the “REMS-associated dream-like biophysical biophotonic representations originated from long-term visual memory,”37. These visual imageries could occur at any time during NDE, but most specifically might occur during the reperfusion state.

An additional concept that researchers are trying to understand is the non-local mind. This theory concludes that consciousness and memories may not be localized or generated primarily in the brain, as the brain no longer functions during NDE2,38. This was witnessed in cardiac arrest patients who had a discontinuance of blood supply to the brain, and yet still reported encountering components of NDE. This is an unexplainable idea of the complex mind-brain relationship that vivid NDE components persist, even when the heart is stopped31. These findings infer that consciousness is non-local, meaning that perhaps, consciousness draws breath separately from the body. However, it should be noted that a number of researchers have refuted this theory as EEG is only able to discern electrical activity in just one half of the area of the cerebral cortex, while activity in the other half may not be detected39,40,41. Additionally, another study found an increased bispectral index values during donation after cardiac death, and changes in processed EEG immediately after withdrawal of life-sustaining care might be linked to dosing of hypnotic or anesthetic drugs42. Further studies are needed during the dying process regarding raw and processed EEGs.

A similar, perhaps closely related, and interesting phenomenon is terminal lucidity. Michael Nahm used the term “terminal lucidity”43 to refer to the short burst of mental clarity, or mental improvement, that may happen soon before the end of life44,45. Dating back 250 years, 83 cases of terminal lucidity were documented by Julius in 1844 in patients with mental disorders who resided in a British asylum44,46. Specifically, terminal lucidity has shown prevalence in individuals with mental disorders that may include Alzheimer’s disease, chronic schizophrenia, patients with brain tumors or brain abscesses, strokes, meningitis, or affective disorders47,48. Relatively, terminal lucidity lasts longer than the surge of EEG or LFP signals in NDE. What causes terminal lucidity is still unknown. A continuous EEG recording during these periods would provide a meaningful hint to the phenomenon.

In the current study, we took advantage of a terminal study when animals were undergoing euthanasia. The rebound activities found at 3 min post-CO2 initiation has the possibility of serving as a window of time at which NDE occurs when near death in humans. With the advantage of implanted LFP electrodes, further research should explore a variety of brain regions, such as brain networks involving memory, emotion, pain, and other sensory and motor centers that could reveal whether the recollection of past experiences or memories may happen through a possible LFP spike. This dynamic euthanasia LFP power changes in the brain are more prominently rooted in the freely-moving group, suggesting that NDE might be more often in a relatively healthier person than in a chronically ill person.

In conclusion, our findings offer insight into the underpinnings of the rat brain in real time during the process of death. We show power spectral changes of the local field potential (LFP) during the process of death, and most interestingly, a rebound surge in LFP in our freely-moving group which we believe closely demonstrates NDEs. This current study points toward the unraveling of the dynamic changes of the brain during the final stage of life. What verily transpires in the brain during the process of death remains to be unknown. Further advancements in research on NDEs by routine EEG monitoring could open the door and help solve the mystery of consciousness, the greatest question of life.

Methods

Animal preparation

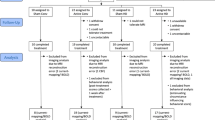

44 adult male Sprague Dawley rats (N = 44) sourced from Charles River, weighing between 300 and 400 g, were conducted in this study. Animals were housed in the Animal Care Facility (ACF) with a 12:12-hr light-dark cycle. Water and food pellets were available ad libitum, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Texas at Arlington. This study was an extension of a separate study where the recording of LFP was conducted using a migraine model19. In some cases, if the data was too noisy due to the potential poor connection of the wireless electrode module, data from that specific animal was justified to be excluded from data analysis. To satisfy these criteria, our final animal groups are the following: freely-moving (n = 18), and anesthetized (n = 21). At the end of each study, euthanasia was performed and a recording of LFP was conducted on these animals.

LFP electrode implantation

The animal was placed in the induction chamber under inhaled isoflurane anesthesia, at an induction rate of 3% and a later maintenance rate of 1.5% inhaled isoflurane anesthesia. After visually observing no movement, the animal was transferred from the induction chamber to the stereotaxic frame and fixed by the rat’s incisor tooth and ear bars. The top of the skin was shaved, and under the aseptic surgical procedure, a 20-mm clean midline incision was made.

Next, using the position of bregma for reference and the coordinates for electrode implantation, four brain regions of interest were used in this study: (1) the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), located at 0 mm posterior to bregma, 0.70 mm lateral, 3.20 mm deep; (2) thalamus (Po), located at 3.72 mm posterior to bregma, 2.20 mm lateral to the right, 5.60 mm deep; (3) trigeminal ganglion (TG), located at 4.30 mm posterior to bregma, 3.40 mm lateral to the left, 10.00 mm deep; and (4) the primary visual cortex (V1M), located at 7.44 mm posterior to bregma, 3.40 mm lateral to the right, 1.60 mm deep, according to the 6th edition brain atlas by Paxinos and Watson49.

The skull surface was first marked, and a burr hole was drilled in the skull for the placement of an electrode. Four 0.010 in. (diameter) bipolar stainless-steel electrodes (Plastics. One, Inc. 81MS3031SPCE) were separately implanted into the four selected regions. Two additional burr holes were drilled. The first burr hole was anterolateral to the bregma for grounding and the second was posterior to the lambda, used as an anchor. Screws (2.6 mm) were turned into the burr holes, and a grounding wire was wrapped around the grounding screw. After the implantation of electrodes, dental cement was used to fix the electrodes to the skull. The electrodes were then connected to the wireless module (designed by SiChuan NeoSource BioTektronics Limited). The wireless module receives brain signals from the areas where the electrodes were placed and transmits them to a dongle that is connected to the computer where the recording software is used to collect data.

Recording

The wireless module recording device was attached to the implanted electrodes. The LFP was recorded under one of two conditions. The first condition was at the end of a recording following about 4.5 h of 1.5% inhaled isoflurane anesthesia to record the LFP from the afore-mentioned brain regions following intraperitoneal (10 mg/kg, i.p.) injection of nitroglycerin (NTG), a well-established migraine model. Therefore, the animal was under isoflurane anesthesia from the start of implantation surgery to the end (anesthetized group). The second condition was after a one-week recovery from implantation surgery. Animals were injected with NTG and LFP was recorded for 4.5 h while animals were freely-moving. At the end of this migraine study, animals underwent the euthanasia process where LFP was recorded for this study. During this process, five minutes of baseline LFP activity was recorded before CO2 was initiated in a single high-concentration deliverance. An additional 30 min of continuous recording was conducted, a total recording time of 35 min.

Data analysis

After the recording process was completed, a text file for each brain region or channel was generated. This data was imported into Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronics Design, UK) to provide a visualization of the raw activity occurring in the brain regions during the recording (Fig. 1). Spike2 was also used to identify noises that were the base for excluding some data points or full data from a rat. It should be noted that the expanded spectrograms on top of Fig. 1 shows a sub-second data processing between 160 and 161 s, which was not a result of using a time window moving by 0.1s or less, but a graph presentation directly from the Spike2 program included in the “Channel Draw Mode.” MATLAB was used to calculate the power of the frequency band by fast Fourier transform (FFT) every 10 s without specifying the window function. The power of each frequency band from each channel was exported to the Excel sheet: delta (0.1–3 Hz), theta (3–7 Hz), alpha (7–12 Hz), beta (12–30 Hz), and gamma (30–100 Hz). This portion of data is represented as 10s raw, and normalization was done by the ratio of each 10s data to the average of the first 5 min (30 data points) (Fig. 2). To perform statistical analysis, the 10s data were merged to a 1-minute raw and normalized data point (Fig. 3).

Correlation coefficient analysis

After obtaining the mean values of the power intensity from five frequency bands in four brain areas (ACC, Po, TG, and V1M), they were then used to calculate the correlation coefficient in Excel. A total of 20 × 20 correlation coefficient values were obtained for the following four conditions: Freely-moving Raw, Freely-moving Normalized, Anesthetized Raw, and Anesthetized Normalized. A heatmap was plotted for each of these conditions (Fig. 4).

Statistical analysis

SPSS software was used to test the statistical significance between the freely-moving and anesthetized groups during the CO2 euthanasia process. A mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc testing was implemented to test the difference of the LFP power changes after CO2 as compared to the baseline. A repeated factorial ANOVA with LSD posthoc test was carried out to test whether the LFP power responses were different among these four regions. All data were presented as mean ± SEM. A significance was determined at p < .05 level.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Charlier, P. Oldest medical description of a near death experience (NDE), France, 18th century. Resuscitation 85(9), e155 (2014).

Van Lommel, P., Van Wees, R., Meyers, V. & Elfferich, I. Near-death experience in survivors of cardiac arrest: a prospective study in the Netherlands. Lancet 358, 2039–2045 (2001).

Greyson, B. Varieties of Near-Death experience. Psychiatry 56, 390–399 (1993).

Roberts, G. & Owen, J. The Near-death experience. Br. J. Psychiatry. 153, 607–617 (1988).

Irwin, H. J. & Bramwell, B. A. The devil in Heaven: A near-death experience with both positive and negative facets. J. Near-Death Stud. 7, 38–43 (1988).

Charpier, S. Between life and death: the brain Twilight zones. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1156368 (2023).

Mashour, G. A., Lee, U. C., Pal, D. & Li, D. Consciousness and the dying brain. Anesthesiology, 140(6), 1221–1231 (2024).

Palmieri, A. et al. Reality of near-death-experience memories: evidence from a psychodynamic and electrophysiological integrated study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 429 (2014).

Borjigin, J. et al. Surge of neurophysiological coherence and connectivity in the dying brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 110, 14432–14437 (2013).

Xu, G. et al. Surge of neurophysiological coupling and connectivity of gamma oscillations in the dying human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 120(19): e2216268120 (2023).

Vicente, R. et al. Enhanced interplay of neuronal coherence and coupling in the dying human brain. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14: 813531 (2022).

Martial, C. et al. Neurophenomenology of near-death experience memory in hypnotic recall: a within-subject EEG study. Sci. Rep. 9 (1):14047 (2019).

Beauregard, M., Courtemanche, J. & Paquette, V. Brain activity in near-death experiencers during a meditative state. Resuscitation 80, 1006–1010 (2009).

Chawla, L. S., Akst, S., Junker, C., Jacobs, B. & Seneff, M. G. Surges of electroencephalogram activity at the time of death: A case series. J. Palliat. Med. 12, 1095–1100 (2009).

Chawla, L. & Seneff, M. G. End-of-life electrical surges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110(44): E4123 (2013).

Parnia, S. et al. AWAreness during REsuscitation - II: A multi-center study of consciousness and awareness in cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 191:109903 (2023).

van Rijn, C. M., Krijnen, H., Menting-Hermeling, S. & Coenen, A. M. L. Decapitation in rats: latency to unconsciousness and the wave of death. PLoS One 6 (1): e16514 (2011).

Kongara, K., McIlhone, A. E., Kells, N. J. & Johnson, C. B. Electroencephalographic evaluation of decapitation of the anaesthetized rat. Lab. Anim. 48, 15–19 (2014).

Wang, Z., Lin, Q. & Peng, Y. B. Multi-region local field potential signatures and brain coherence alternations in response to nitroglycerin-induced migraine attacks. Headache 63, 523–538 (2023).

Wang, Z. & Peng, Y. B. Multi-region local field potential signatures in response to the formalin-induced inflammatory stimulus in male rats. Brain Res. 1778: 147779 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Piezoelectric ultrasound energy-harvesting device for deep brain stimulation and analgesia applications. Sci. Adv. 8 (15): eabk0159 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation of periaqueductal Gray for analgesia. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 3155–3162 (2022).

Trejo, J., Izuagbe, M., Killian, K., Wang, Z. & Peng, Y. Local field potential change during euthanasia in Society for Neuroscience, (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Near-death high-frequency hyper-synchronization in the rat hippocampus. Front. Neurosci. 13:800 (2019).

Chawla, L. S. et al. Characterization of end-of-life electroencephalographic surges in critically ill patients. Death Stud. 41, 385–392 (2017).

Blackmore, S. Dying to Live: Science and Near-Death Experience. London: Grafton (1993).

Klemenc-Ketis, Z., Kersnik, J. & Grmec, S. The effect of carbon dioxide on near-death experiences in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors: a prospective observational study. Crit. Care 14(2): R56 (2010).

Meduna, L. The effect of carbon dioxide upon the function of the brain. In L. J. Meduna, Carbon Dioxide Therapy: A Neurophysiological Treatment of Nervous Disorders, Charles C Thomas Publisher, 17–36 (1950).

Jon Hansen, A. Effect of anoxia on ion distribution in the brain. Physiol. Rev. 65(1): 101–48 (1985).

Clute, H. & Levy, W. Electroencephalographic changes during brief cardiac arrest in humans. Anesthesiology 73, 821–825 (1990).

Trent-Von Haesler, N. & Beauregard, M. Near-death experiences in cardiac arrest: implications for the concept of non-local Mind. Rev. Psiq Clín. 40, 197–202 (2013).

Blackmore, S. Near-death experiences. J. R Soc. Med. 89, 73–76 (1996).

Braithwaite, J. Towards a cognitive neuroscience of the dying brain. Skeptic 21, 8–17 (2008).

Blackmore, S. J. & Troscianko, T. S. The physiology of the tunnel. J. Near-Death Stud. 8(1): 15–28 (1989).

Aserinsky, E. & Kleitman, N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. Sci. (1979). 118, 273–274 (1953).

Kondziella, D., Dreier, J. P. & Olsen, M. H. Prevalence of near-death experiences in people with and without REM sleep intrusion. PeerJ (2019). (2019).

Bókkon, I., Mallick, B. N. & Tuszynski, J. A. Near death experiences: A multidisciplinary hypothesis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 533 (2013).

Van Lommel, P. Non-local consciousness A concept based on scientific research on Near-Death experiences during cardiac arrest. J. Conscious. Stud. 20, 7–48 (2013).

French, C. C. Near-death experiences in cardiac arrest survivors. Prog Brain Res. 150, 351–367 (2005).

Paolin, A. et al. Reliability in diagnosis of brain death. Intensive Care Med. 21, 657–662 (1995).

Bardy, A. Near-death experiences. Lancet 359, 2116 (2002).

Auyong, D. B. et al. Processed electroencephalogram during donation after cardiac death. Anesth. Analg. 110, 1428–1432 (2010).

Nahm, M. Terminal lucidity in people with mental illness and other mental disability: an overview and implications for possible explanatory models. J. Near-Death Stud. 28, 87–106 (2009).

Chiriboga-Oleszczak, B. A. Review paper. Terminal lucidity. Curr. Probl. Psychiatry. 18, 34–46 (2017).

Kheirbek, R. E. Terminal lucidity. J. Palliat. Med. 22, 1023 (2019).

Nahm, M., Greyson, B., Kelly, E. W. & Haraldsson, E. Terminal lucidity: A review and a case collection. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 55, 138–142 (2012).

Nahm, M. & Greyson, B. The death of anna Katharina Ehmer: A case study in terminal lucidity. Omega (United States). 68, 77–87 (2013).

Nahm, M. & Greyson, B. Terminal lucidity in patients with chronic schizophrenia and dementia: L survey of the literature. J. Nerv. Mental Disease. 197, 942–944 (2009).

Paxinos, G. & Watson, C. The Rat Brain, in Stereotaxic Coordinates 6th Edn (Academic, 2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the PhD Dissertation Fund from the Department of Psychology at the University of Texas at Arlington.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. and Y.B.P. designed the experiment; Z.W. performed data collection; J.T. and Y. B. P. analyzed data, including statistical analysis; J.T. wrote the first complete draft of the paper and K.M.K. contributed a portion of the draft. Y. B. P. revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All methods detailed in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Texas at Arlington and in strict accordance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trejo, J., Killian, K.M., Wang, Z. et al. Local field potential changes during euthanasia may parallel with near death experience. Sci Rep 15, 11404 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92723-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92723-0