Abstract

Magneto-optical (MO) metamaterials are a new degree of freedom in the modern technologies due to their pivotal role in paving way for appealing applications. In this paper, a new type of metamaterial composed of plasma and ferrite layers is proposed, and based on the matrix method and numerical calculations is characterized. It is identified that plasma-ferrite metamaterial (PFMM) exhibits a significant MO response with large polarization rotation angles and ellipticities in both reflection and transmission geometries. In some cases, the peak values of the Faraday and polar Kerr rotation angles exceed 40 degrees and demonstrate high sensitivity to changes in external parameters. Moreover, cross-polarization conversion effect and its adjustability under the influence of the external magnetic field and plasma number density in the vicinity of magnetic resonance frequency are verified. The results reveal that such multifunctional structure can provide opportunities for developing compact high-performance MO devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, further development of magneto-optical (MO) materials has brought about significant opportunities for new advancements in sensing1, circulators2, insulators3, filters4,5, spintronics6,7, and more. MO effects encompass all phenomena where the presence of a quasi-static magnetic field in a medium manipulates the propagation characteristics of passing electromagnetic (EM) waves via induced birefringence or dichroism8. In medium exhibiting such properties, known as gyromagnetic or gyrotropic, propagation of right and left rotating elliptical polarizations with different speeds gives rise to a number of notable phenomena9. Two of the most commonly and widely used MO effects are MO Faraday effect (MOFE) and MO Kerr effect (MOKE) which involve the rotation of polarization for transmitted and reflected waves, respectively10,11,12. It is believed that MOFE and MOKE are originated from coupling between the electric and magnetic components of incident EM waves, resulting in non-zero off-diagonal elements in dielectric matrix, which in turn creates a difference in the real parts of the refractive indices of magnetic materials for right and left circularly polarized waves13. Since these phenomena arise from contact-free and non-destructive methods in both transmission and reflection geometries, they serve as powerful tools for characterizing various material properties and fabricating nonreciprocal devices. Hence, enhancement of both MOFE and MOKE would offer intriguing applications in applied physics and engineering. In this regard, several past years have witnessed to considerable efforts for increasing MOFE and MOKE through diverse methods14,15,16,17,18,19. More remarkably, the work in Ref.14 deals with a strong Faraday rotation (FR) in single and multilayer graphen through both classical and quantum regimes. Also, the work in Ref.15 reports synergetic interaction between dark mode and FR using core-shell geometry. Moreover, other particle-based methods have been used theoretically and experimentally in Refs.16 and17, respectively.

One of the good candidate to enhancement of MO rotations is to use magnetic materials in multilayer structures and metamaterials20,21,22. It is emphasized that cyclotron resonances in these artificial materials provide strong polarization rotation for incoming EM waves. In general, stratified metamaterials are sub-wavelength manmade materials in which electric permittivity and magnetic permeability exhibit simultaneously negative values within specific frequency ranges. Podolskiy et al.23 were pioneers in utilizing simple stratified structures as metamaterials, where alternating layers of two conventional materials create a left-handed medium with a negative refractive index. Later, some others have noted the ability of such inhomogeneous media, particularly in the presence of external parameters like electric and magnetic fields, to modify incoming EM waves24,25,26,27. In the meantime, undeniable prevalence of plasma applications has eclipsed layered metamaterial technologies, sparking a growing interest in exploring the MO properties of plasma metamaterials28,29,30.

It is well established that variations in internal parameters of plasma, such as electron density and pressure, allow it to cover a wide domain of operational EM bands. Additionally, swiftly control of plasma permittivity through external parameters makes it highly suitable for fabricating tunable structures31,32,33. Placing a ferrite layer next to the plasma enhances the controllability of EM waves even further, as the magnetic permeability of the ferrite is greatly influenced by the imposed external magnetic field34,35,36,37.

Motivated by these unique capabilities, in this paper we endeavor to describe an adjustable metamaterial consisting of ferrite and plasma layers, and demonstrate MO Faraday and polar Kerr effects with this layout. To achieve this, we employ \(4\times 4\) matrix method38 to govern the intricacy of various polarization modes propagating through such an anisotropic structure, then analyze obtained results through several numerical simulations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In section “Theoretical approach”, we first apply the \(4\times 4\) matrix formalism to determine the reflection and transmission coefficients, along with their FR and polar Kerr rotation (KR) angles. In section “Results and discussion”, we analyze the output results based on numerical simulations, and discuss the plasma-ferrite metamaterial’s (PFMM) capability to induce polarization rotation of outgoing waves through MOFE and MOKE. Section “Conclusions” summarizes the conclusions drawn from this research.

Theoretical approach

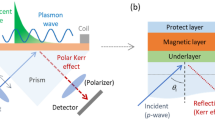

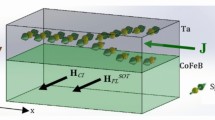

Schematic view of the incident beam interaction with plasma-ferrite (PF) structure is illustrated in Fig. 1. It has been shown that a linearly polarized plane beam with wave vector \(\vec {k}\) normally incident on the surface of a PF composite, and then partially reflect from and transmit through the considered structure. It is assumed that oxyz is a global coordinate system, both incident beam and external magnetic field \(\vec {H}_{0}\) are aligned along the \(\hat{z}\)-direction, \(d_{P}\) is the thickness of a plasma layer, and \(d_{F}\) is the thickness of a ferrite layer. Furthermore, it is supposed that the incoming beam wavelength \((\lambda )\) is much greater than the width \((\ell =d_{P}+d_{F})\) of the PFMM.

In the presence of external magnetic field along the \(\hat{z}\)-direction, the electric permittivity of the plasma layer can be described as39

Here, \(\varepsilon _{1}=1-\omega _{p}^2 (\omega +i\nu )/\omega [(\omega +i\nu )^2-\omega _{c}^2]\), \(\varepsilon _{2}=-\omega _{p}^2 \omega _{c}/\omega [(\omega +i\nu )^2-\omega _{c}^2]\), and \(\varepsilon _{3}=1-\omega _{p}^2/\omega\)\((\omega +i\nu )\), where \(\nu\) is the collisional frequency, \(\omega _{c}=eH_{0}/cm_{e}\) is the electron cyclotron frequency, and \(\omega _{p}=\sqrt{4\pi n_{e}e^{2}/m_{e}}\) is the plasma electron frequency. Also, \(H_{0}\) is the static magnetic field, \(m_{e}\) is the electron mass, and \(n_{e}\) is the electron or plasma number density.

In such conditions, the magnetic permittivity of the ferrite layer becomes34

wherein, \(\mu _{1}=1+\omega _{m} (\omega _{0}+i\alpha \omega )/[(\omega _{0}+i\alpha \omega )^2-\omega ^2]\), \(\mu _{2}=\omega _{m} \omega /[(\omega _{0}+i\alpha \omega )^2-\omega ^2]\), and \(\mu _{3}=\mu _{0}\). Also, \(\omega _{0}=2\pi \gamma H_{0}\) is the resonance frequency, \(\omega _{m}=2\pi \gamma M_{0}\) is the characteristic circular frequency, \(\mu _{0}\) is the vacuum magnetic permeability, \(\gamma =2.8\) MHz/Oe is the gyromagnetic ratio, \(M_{0}\) is the saturation magnetization, and \(\alpha\) is the damping rate.

Based on our initial assumption, \(\lambda \gg \ell\), the PFMM can be described as a homogeneous medium with effective material parameters. To find them, let’s employ the averaging procedure proposed in40 and41, which leads to average permittivity and permeability tensors of PFMM as follows, respectively

and

Now, with the structure’s characteristics specified, we can obtain the transmission and reflection coefficients using the \(4\times 4\) matrix method detailed in references42 and43. To achieve this, we begin with Maxwell’s equations and eliminate the longitudinal components, allowing us to express the compact wave equation propagating in an anisotropic structure as follows

where, \(k_0=\omega / c\), \(\vec {\psi }= \left[ \begin{array}{cccc} \sqrt{\varepsilon _{0}} E_{x}(z)&\sqrt{\mu _{0}} H_{y}(z)&\sqrt{\varepsilon _{0}} E_{y}(z)&\sqrt{\mu _{0}} H_{x}(z) \end{array} \right] ^{T}\), and \(\bar{H}\) is coefficient matrix or characteristic matrix extracted from combination of PFMM average parameters. Using some normalized parameters as \(\tilde{k}_{x}=k_{x}/k_{0}\), \(\tilde{k}_{y}=k_{y}/k_{0}\), \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{11}=\varepsilon _{11}/\varepsilon _{0}\), \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{12}=\varepsilon _{12}/\varepsilon _{0}\), \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{21}=\varepsilon _{21}/\varepsilon _{0}\), \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{22}=\varepsilon _{22}/\varepsilon _{0}\), \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{33}=\varepsilon _{33}/\varepsilon _{0}\), \(\tilde{\mu }_{11}=\mu _{11}/\mu _{0}\), \(\tilde{\mu }_{12}=\mu _{12}/\mu _{0}\), \(\tilde{\mu }_{21}=\mu _{21}/\mu _{0}\), \(\tilde{\mu }_{22}=\mu _{22}/\mu _{0}\), and \(\tilde{\mu }_{33}=\mu _{33}/\mu _{0}\) , the element of \(\bar{H}\) can be written as

Suggested four periodic solutions for Eq. (5) are represented in the form \(\vec {\psi }_{j}(z)=\vec {\psi }_{j}(0)\exp [i\rho _{j}z]\), where \(j=\{1,2,3,4\}\), and \(\rho _{j}\) is the longitudinal component of wave vector. Substituting these solutions into the Eq. (5) leads to deriving the transfer matrix of the transverse magnetic and electric field components in each unit cell with the thickness \(\ell\) as \(\bar{\delta }(\ell )=\bar{\Psi }\bar{Q}(\ell )\bar{\Psi }^{-1}\), in which \(\bar{Q}(\ell )\) is a diagonal \(4\times 4\) matrix whose elements are \(\exp [i\rho _{j}\ell ]\), and \(\bar{\Psi }\) is a \(4\times 4\) matrix composed of \(k_{0}\bar{H}\) eigenvectors. It is evident that the transfer matrix for a multilayer structure is obtained through chain multiplication as

wherein, subscribes i and t respectively refers to incident and transmitted beams, \(\Delta _{i}= \left[ \begin{array}{cccc} E_{i}^{p}&E_{r}^{p}&E_{i}^{s}&E_{r}^{s} \end{array} \right] ^{T},\) \(\Delta _{t}= \left[ \begin{array}{cccc} E_{t}^{p}&0&E_{t}^{s}&0 \end{array} \right] ^{T}\), \(\bar{\mathbb {T}}\) being the total transfer matrix, and \(\xi _{q}\) with \(q\in \{i,t\}\) being dynamical matrix derived from boundary conditions as

Real and imaginary parts of effective permittivity and permeability of PFMM versus input wave frequency for (a) \(H_{0}=400\) Oe and \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\), (b) \(H_{0}=500\) Oe and \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\), (c) \(H_{0}=450\) Oe and \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\), and (d) \(H_{0}=450\) Oe and \(n_{e}=5\times 10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\). The insets provide a zoomed-in view of the resonance regions.

First row shows the normalized reflection and transmission coefficients as a function of incident beam frequency for different values of external magnetic field with \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\). Second row depicts the reflection and transmission coefficients as a function of incident beam frequency for different values of electron number density with \(H_{0}=450\) Oe. The insets provide a zoomed-in view of the resonance regions.

Let it be clarified that \(n_{q}\) represents the refractive index of the entrance and exit regions, while s and p denote the polarization of the electric field. Now, the total polarization dependent transmission coefficients for reflected and transmitted beams from a magnetized PFMM can be expressed as

Where, \(\mathbb {T}_{\zeta \varpi }\) are the elements of total transfer tensor with \(\zeta\), \(\varpi\) \(\in \{1,2,3,4\}\), and the first and second subscripts indicate the input and output polarizations, respectively.

From the obtained polarization dependent coefficients, the FR and KR angles44,45,46 together with their corresponding ellipticities for incident s-polarized beams are given by

The characteristic MOFR and MOKR angles and their ellipticities are typically combined into the complex angles written as \(\chi _{F}=\theta _{F}+i \eta _{F}\) and \(\chi _{K}=\theta _{K}+i \eta _{K}\), respectively. Physically, \(\theta _{\sigma }\) represents the rotation of the plane of polarization of the output beam relative to that of the incident beam. On the other hand, \(\eta _{\sigma }\) denotes the ellipticity associated with the phase and amplitude differences between left-circularly polarized and right-circularly polarized waves. In simpler terms, \(\theta _{\sigma }\) indicates the angle between the original plane of polarization and principal axis of the elliptically polarized outgoing beam. Meanwhile, \(\tan \eta _{\sigma }\) describes the ratio of the minor axis to the major axis of the ellipse that characterizes the polarization of the outgoing beam47.

Results and discussion

We will now proceed with the numerical analysis of reflection, transmission, and the polarization characteristics, including rotations and ellipticities, of both forward and backward waves in the proposed PFMM. For this analysis, we consider Yttrium Iron Garnet (YIG) as the ferromagnetic layer which is characterized by the parameters \(M_{0}=1750\) Oe, \(d_{F}=0.05\) \(\text {cm}\), \(\varepsilon _{F}=25\), and \(\alpha =0.002\)34. Also, plasma layer is characterized by the following parameters \(\nu =0.01\) GHz, and \(d_{P}=0.05\) cm.

Parts (a) and (b) respectively depict polarization ellipses of transmitted and reflected beams for \(\omega =7\times 10^{9}\) Hz, \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\), and different values of external magnetic field. Parts (c) and (d) respectively show polarization ellipses of transmitted and reflected beams for \(\omega =8\times 10^{9}\) Hz, \(H_{0}=450\) Oe, and different values of electron number density.

Parts (a) and (b) respectively show polarization conversion ratios of the transmitted and reflected beams for \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\) and different values of external magnetic field. Parts (c) and (d) respectively represent polarization conversion ratios of the transmitted and reflected beams for \(H_{0}=450\) Oe and different values of electron number density.

Initially, we focus on the frequency range where the PF structure exhibits a negative refractive index, thereby functioning as a metamaterial. To this end, based on the Maxwell equations the effective refractive index of PF structure is derived as \(N_{\pm }^{2}=(\varepsilon _{11}\pm i\varepsilon _{21})(\mu _{11}\pm i\mu _{21})\) in which \(\varepsilon _{eff}=\varepsilon _{11}\pm i\varepsilon _{21}\) being the effective permittivity and \(\mu _{eff}=\mu _{11}\pm i\mu _{21}\) being the effective permeability of structure. Additionally, the subscripts \(``+''\) and \(``-''\) correspond to the ordinary and extraordinary waves, respectively. In order to attain a negative refractive index, it is essential that both the permittivity and permeability of the material are negative \((\varepsilon _{eff}<0\) and \(\mu _{eff}<0)\)48. Here, it can be easily demonstrated that, for extraordinary waves, the effective permeability \((\mu _{eff})\) cannot be negative. Therefore, only the ordinary waves are potential candidates for exhibiting a negative refractive index. In this regard, Fig. 2 shows the evolution of real and imaginary parts of the effective permittivity \((\varepsilon _{eff})\) and permeability \((\mu _{eff})\) of PF against the incident frequency \((\omega )\), with different values of external magnetic field and electron number density. In the upper row of this figure, it is observed that for \(H_{0}=400\) Oe and \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\) both real parts of \(\varepsilon _{eff}\) and \(\mu _{eff}\) exhibit negative values around the \(\omega =7\times 10^{9}\) Hz. Keeping \(n_{e}\) constant and increasing \(H_{0}\) up to \(H_{0}=500\) Oe, the resonance locations moves toward higher frequencies and their amplitudes decrease. To illustrate the tunability of the \(\varepsilon _{eff}\) and \(\mu _{eff}\) with variations of \(n_{e}\), lower row of the Fig. 2 is plotted for fixed values of \(H_{0}=450\) Oe, and two different values of \(n_{e}\). It is evident that increasing electron number density from \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\) to \(n_{e}=5\times 10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\) does not significantly affect the displacement of the resonance frequency but instead increases the value of \(\varepsilon _{eff}\) in the resonance region. It should be noted that the imaginary components of effective permittivity and permeability, which indicate the medium’s losses49, exhibit peak values at the transition points of the corresponding real curves, and their evolution is similar to that of the real parts.

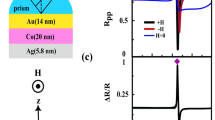

To show the influence of parameter changes in the adjusting of output energy, the normalized reflection and transmission coefficients has been plotted against the incident frequency for different values of \(H_{0}\) and \(n_{e}\). In the first row of Fig. 3, it can be seen that both reflected and transmitted spectra exhibit maximum values in the proximity of resonance frequency. Increasing external magnetic field from \(H_{0}=400\) Oe to \(H_{0}=500\) Oe causes to displacement of output beam peak positions toward high incident frequencies. In the second row, the reflected and transmitted spectra have been illustrated for \(H_{0}=450\) Oe and two different values of \(n_{e}\). It is shown that, compared to the first row, the peak positions in both reflected and transmitted spectra slightly shift as \(n_{e}\) increases. Moreover, the output peak values rise with the increase in \(n_{e}\). This phenomenon may be attributed to the increment in the effective permittivity of the structure, resulting from the higher electron number density.

To further explore the resonance regions, we have concentrated on these areas and provided zoomed-in views, shown as insets in Fig. 3. Upon closer inspection of the reflected and transmitted waves in these frequency domains, it is concluded that increasing plasma number density leads to a separation of the sharp peaks observed in the resonant regions. Physically, this can be attributed to the differences in propagation conditions for right- and left-circularly polarized waves in the PFMM structure. Indeed, a linearly polarized beam can be considered as a superposition of right- and left- circularly polarized components. When such a beam passes through a MO layer, the difference in the refractive index for each component causes their velocities to differ. Consequently, their recombination in the output plane results in the generation of new pass-bands50,51,52,53. However, increasing the external magnetic field does not significantly affect the shape of the resonance regions in the reflected and transmitted spectra. This may occur because the external magnetic field is not strong enough to induce more noticeable changes. As a result, the right- and left- circularly polarized components exhibit the same response and merge into an almost similar shape.

The real and imaginary parts of FR and KR angles as a function of wave frequency have been depicted in Fig. 4 for \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\) and two different values of \(H_{0}\). From this figure it is dedicated that both FR and KR angles along with their ellipticites are maximized around the frequency band which the system exhibits left-handed behavior, and almost reach their upper limit. Such a strong rotation of polarization in transmitted and reflected beam, together with the change in ellipticity, is a result of the resonances arising from the cyclotron effect in the classical regime. Figure 4a and c show that the direction of polarization rotation in the pre-resonance frequencies is opposite to the post-resonance regions. Moreover, it is concluded from Fig. 4b and d that linearly polarized beam in the resonance state becomes elliptically polarized after outgoing from slab. It should be noted that in our proposed structure the maximum value of ellipticity for polar Kerr effect exceeds that obtained from the Faraday effect. By increasing the external magnetic field, resonance shape of spectra for \(\theta _{F}\), \(\theta _{K}\), \(\eta _{F}\), and \(\eta _{K}\) shift toward high energy band, and they are slightly broadened. We see such a similar phenomenon for reflected and transmitted spectra as a result of \(H_{0}\) variation. This results suggest that giant values of FR and KR angles alongside high transmission and reflection coefficients can be simultaneously kept in proposed composite. This coexistence demonstrates that the increment of polarization rotation angles is influenced by the strong localization of EM waves.

The dependence of FR and polar KR angles accompanied by their ellipticites on the variation of electron number density has been shown in Fig. 5 for a fixed value of \(H_{0}=450\) Oe. Similar to Fig. 4, the maximum values of reflected and transmitted spectra for various values of electron number density occur near the resonance frequency. However, it seems that increasing electron number density from \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\) to \(n_{e}=5\times 10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\) does not have a remarkable effect on the displacement of the peak values. This result indicates that the dependency of the polarization rotation shifts in PFMM on the external magnetic field is stronger than its dependency on the electron number density. However, by examining the polarization rotations in the resonance regions, it becomes evident that increasing the plasma number density leads to a separation of the polarization rotation peaks in this specific area and results in the emergence of new fluctuations alongside the primary peaks. This phenomenon can be attributed to changes in the off-diagonal elements of the effective permittivity tensor as the plasma frequency increases. Consequently, at higher plasma number densities, the difference between the refractive indices of the right- and left-circularly polarized components increases, causing the peaks of the FR and polar KR to separate50,51,52,53.

To highlight the different sensivity of \(\theta _{F}\) and \(\theta _{K}\) to the adjustable parameters, in the Fig. 6 we plot the contours of FR and polar KR angles as a function of external magnetic field and electron number density for fixed value of incident wave frequency as \(\omega =8\times 10^{9}\) Hz. It appears that the fluctiations of contors for a constant value of \(n_{e}\) are greater than their fluctuations when \(H_{0}\) is held constant. In addition, at this specified incident wave frequency, the variation of \(n_{e}\) has a more pronounced effect on MO rotations in weaker \(H_{0}\) compared to stronger \(H_{0}\). Overall, this figure clearly demonstrates that the considered structure possesses the necessary capability to achieve any desired polarization state of the EM beam by adjusting external parameters.

To visualize the polarization states of the transmitted and reflected beams, considered system is illuminated with a linearly polarized wave, where the electric field is denoted as \(\vec {E}_{in}=E_{in}^{s}exp(i\varphi _{in}^{s})\hat{s}\). In this situation, the transmitted and reflected beams respectively can be written as \(\vec {E}_{T}=E_{T}^{s}exp(i\varphi _{T}^{s})\hat{s}+E_{T}^{p}exp(i\varphi _{T}^{p})\hat{p}\) and \(\vec {E}_{R}=E_{R}^{s}exp(i\varphi _{R}^{s})\hat{s}+E_{R}^{p}exp(i\varphi _{R}^{p})\hat{p}\), in which \(\hat{s}=-\sin \vartheta \hat{x}+\cos \vartheta \hat{y}\) and \(\hat{p}=\cos \vartheta \hat{x}+\sin \vartheta \hat{y}\). Therefore, the phase differences between the orthogonal electric fields of the transmitted and reflected waves are respectively defined as \(\Delta \varphi _{T}=\varphi _{T}^{p}-\varphi _{T}^{s}\) and \(\Delta \varphi _{R}=\varphi _{R}^{p}-\varphi _{R}^{s}\)54. Fig. 7 displays polarization ellipses of transmitted (left column) and reflected (right column) beams under the influence of variable parameters. In the upper row, the effects of external magnetic field variations on the polarization ellipses of outgoing beams have been shown with \(n_{e}=10^{10}\) \(\text {cm}^{-3}\), and \(\omega =7\times 10^{9}\) Hz. It turns out that at the lower \(H_{0}\) the polarization shapes of the extracted beams have a striking elliptical state. Figure 7c and d, which are plotted for \(\omega =8\times 10^{9}\) Hz, \(H_{0}=450\) Oe, and two different values of electron number density, indicate that at the lower \(n_{e}\) the outgoing beams decline to maintain their primary polarization states. It is also observed that with an increase in both parameters \(H_{0}\) and \(n_{e}\), the direction of polarization rotation of the ellipses in the transmitted and reflected states is opposite.

To further representation the PFMM performance in polarization conversion process, we define the polarization conversion rate (PCR) as a measure of the fraction of energy transformed from the original polarization to another polarization state after exiting the slab. It is well known that in the presence of anisotropy, an incident wave with a specific polarization can produce an outgoing wave with a different polarization. For the s-polarized incident wave, PCR of reflected (\(PCR_{R}\)) and transmitted (\(PCR_{T}\)) beam given by20,24

It is clear that the complete polarization conversion occurs when in the reflected and transmitted planes \(R^{ss}\) and \(T^{ss}\) become zero, respectively. Figure 8a and b illustrate the \(PCR_{T}\) and \(PCR_{R}\) versus incident frequencies with the similar parameters employed in the Fig. 4. It is seen that both PCR for transmitted and reflected beams reach their maximum values around the resonance frequency, and meet approximately the complete polarization conversion condition (\(PCR\cong 1\)). It means that in that point, the incident s-polarized wave is fully converted into a p-polarized wave at the outgoing plane. Also, these maximum values is sensitive to the variation of \(H_{0}\), so that higher magnetization values result in the peak points shifting toward higher frequencies. In regions far from the resonance band, there is minimal manipulation of the polarization mode of the outgoing beams, and the PCR spectra asymptotically approach zero. Figure 8c and d, which are plotted for \(H_{0}=450\) Oe, signify that by increasing electron number density the peak value of \(PCR_{T}\) quenches, while, the peak value of \(PCR_{R}\) enhances. Additionally, in both transmitted and reflected PCR spectra, changes in electron number density do not result in significant shifts in the peak positions. It is worth noting that, as discussed in detail in Figs. 3 and 5, peak splitting in the resonance region can also be observed here with an increase in plasma number density.

Eventually, to offer a clearer perspective on the polarization conversion effect, in Fig. 9a and b we present the maximum values of \(PCR_{T}\) alongside \(PCR_{R}\) for different values of the external magnetic field and electron number density, respectively. Figure 9a, plotted for fixed value of \(n_{e}\), illustrates that there is always a point in the \(PCR_{R}\) spectrum where the cross-polarization state of the beam can appear with high purity, however, this effect does not consistently occur for the transmitted beam. Such a response of the structure is a consequence of the variation in the reflection and transmission coefficients of the cross-polarization state55,56. Figure 9b shows that the difference between maximum values of \(PCR_{R}\) and \(PCR_{T}\) is maintained even when \(H_{0}\) remains constant while \(n_{e}\) changes. It is also observed that for high electron number densities, the s-polarized incident wave is simultaneously converted into reflected cross-polarized and transmitted co-polarized waves. This phenomenon provides versatile applications in various fields related to polarization manipulation.

Conclusions

In summary, this paper has theoretically demonstrated how the magneto-optical (MO) states of reflected and transmitted beams from plasma-ferrite metamaterial (PFMM) can be manipulated by varying certain external parameters. To achieve this goal, generalized Berman’s \(4\times 4\) matrix formalism has been employed to determine the outgoing beam coefficients, Faraday rotation (FR), and polar Kerr rotation (KR) angles.

Based on numerical calculations it has been identified that our proposed structure exhibits negative refractive index, and remarkable reflectance and transparency in the proximity of magnetic resonance frequency. Furthermore, it was observed a significant FR and polar KR angles in this frequency range. In the following, the manipulation of MO rotation angles and ellipticities by tuning the external magnetic field and plasma number density was confirmed, and it has been found out that the proposed metamaterial can readily convert the polarization states of both reflected and transmitted waves into their orthogonal counterparts. We expect that our results can open up a novel possibility to develop active nonreciprocal MO devices, and serve as a reference for the miniaturization of tunable wave polarization converters.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, G., Jin, Z. & Chen, J. A review: Magneto-optical sensor based on magnetostrictive materials and magneto-optical material. Sens. Actuators Rep. 5, 100152 (2023).

Xi, X. et al. Polarization-independent circulator based on ferrite and plasma materials in two-dimensional photonic crystal. Sci. Rep. 8, 7827 (2018).

Zhu, W. Q. & Shan, W. Y. Theoretical studies of magneto-optical Kerr and Faraday effects in two-dimensional second-order topological insulators. Sci. Rep. 13, 12599 (2023).

Logue, F. D., Briscoe, J. D., Pizzey, D., Wrathmall, S. A. & Hughes, I. G. Better magneto-optical filters with cascaded vapor cells. Opt. Lett. 47, 2975–2978 (2022).

Tang, G., Huang, Y., Chen, J., Li, Z. Y. & Liang, W. Controllable one-way add-drop filter based on magneto-optical photonic crystal with ring resonator and microcavities. Opt. Express 30, 28762–28773 (2022).

Nemec, P., Fiebig, M., Kampfrath, T. & Kimel, A. V. Antiferromagnetic opto-spintronics. Nat. Phys. 14, 229–241 (2018).

Gish, J. T., Lebedev, D., Song, T. W., Sangwan, V. K. & Van der Hersam, M. C. Waals opto-spintronics. Nat. Electron. 7, 336–347 (2024).

Aoyagi, Y. & Kajikawa, K. Optical Properties of Advanced Materials, Optical Properties of Advanced Materials (Springer, Berlin, 2013).

Shen, J. Q. Negative refractive index in gyrotropically magnetoelectric media. Phys. Rev. B 73, 045113 (2006).

Visnovsky, S., Postava, K. & Yamaguchi, T. Magneto-optic polar Kerr and Faraday effects in periodic multilayers. Opt. Express 9, 158–171 (2001).

Martinez, J. C., Jalil, M. B. A. & Tan, S. G. Giant Faraday and Kerr rotation with strained graphene. Opt. Lett. 37, 3237–3239 (2012).

Ding, N. et al. Magneto-optical Kerr effect in ferroelectric antiferromagnetic two-dimensional heterostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 22282–2229 (2023).

Szechenyi, G., Vigh, M., Kormanyos, A. & Cserti, J. Transfer matrix approach for the Kerr and Faraday rotation in layered nanostructures. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 28, 375802 (2016).

Crassee, I. et al. Giant Faraday rotation in single- and multilayer grapheme. Nat. Phys. 7, 48–51 (2011).

Mazor, Y., Meir, M. & Ben Steinberg, Z. Dark mode-Faraday rotation synergy for enhanced magneto-optics. Phys. Rev. B 95, 035115 (2017).

Varytis, P., Pantazopoulos, P. A. & Stefanou, N. Enhanced Faraday rotation by crystals of core-shell magnetoplasmonic nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 93, 214423 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Plasmonics and enhanced magneto-optics in core-shell Co-Ag nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 11, 1237–1240 (2011).

Belotelov, V. I. et al. Enhanced magneto-optical effects in magnetoplasmonic crystals. Nat. Nanotech. 6, 370–376 (2011).

Mukherjee, A. et al. Giant magneto-optical Kerr enhancement from films on SiC due to the optical properties of the substrate. Phys. Rev. B 99, 085440 (2019).

Hao, J. et al. Manipulating electromagnetic wave polarizations by anisotropic metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 063908 (2007).

Luo, X., Zhou, M., Liu, J., Qiu, T. & Yu, Z. Magneto-optical metamaterials with extraordinarily strong magneto-optical effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 131104 (2016).

Lofy, J., Gasparian, V., Gevorkian, Z. & Jodar, E. Faraday and Kerr Effects in right and left-handed films and layered materials. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 59, 243–251 (2020).

Podolskiy, V. A. & Narimanov, E. E. Strongly anisotropic waveguide as a nonmagnetic left-handed system. Phys. Rev. B 71, 201101 (2005).

Hao, J. & Zhou, L. Electromagnetic wave scatterings by anisotropic metamaterials: Generalized \(4 \times 4\) transfer-matrix method. Phys. Rev. B 77, 094201 (2008).

Rukhlenko, I. D., Premaratne, M. & Agrawal, G. P. Theory of negative refraction in periodic stratified metamaterials. Opt. Express 18, 27916–27929 (2010).

Gnawali, R. et al. A simplified transfer function approach to beam propagation in anisotropic metamaterials. Opt. Commun. 461, 125235 (2020).

Shi, Y. et al. Optical manipulation with metamaterial structures. Appl. Phys. Rev. 9, 031303 (2022).

Sakai, O. & Tachibana, K. Plasmas as metamaterials: A review. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 21, 013001 (2012).

Mehdian, H., Mohammadzahery, Z. & Hasanbeigi, A. Optical and magneto-optical properties of plasma-magnetic metamaterials. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 48, 305101 (2015).

Nobahar, D., Khorram, S. & Rodrigues, J. D. Vortex beam manipulation through a tunable plasma-ferrite metamaterial. Sci. Rep. 11, 16048 (2021).

Nobahar, D., Hajisharifi, K. & Mehdian, H. Twisted beam shaping by plasma photonic crystal. J. Appl. Phys. 124, 213102 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Transmission properties in plasma photonic crystal controlled by magnetic fields. Photonics 10, 333 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Propagation characteristics of obliquely incident terahertz waves in inhomogeneous microplasma. Phys. Plasmas 31, 082115 (2024).

Baden, A. J. Ferrites at Microwave Frequencies 2nd edn. (Peter Peregrinus, London, 1987).

Guo, S., Mao, M., Zhou, Z., Zhang, D. & Zhang, H. The wide-angle broadband absorption and polarization separation in the one-dimensional magnetized ferrite photonic crystals arranged by the Dodecanacci sequence under the transverse magnetization configuration. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 54, 015004 (2021).

Nobahar, D. & Khorram, S. Terahertz vortex beam propagation through a magnetized plasma-ferrite structure. Opt. Laser Technol. 146, 107522 (2022).

Ali, R., Zamir, B. & Shah, H. A. Transverse electric surface waves in a plasma medium bounded by magnetic materials. Results Phys. 8, 243–248 (2018).

Mackay, T. G. & Lakhtakia, A. The transfer-matrix method in electromagnetics and optics (Springer Nature, Switzerland AG, 2020).

Ginzberg, V. L. The Propagation of Electromagnetic Waves in Plasmas (Pergamon, New York, 1970).

Agranovich, V. M. Dielectric permeability and influence of external fields on optical properties of superlattices. Solid State Commun. 78, 747 (1991).

Eliseeva, S. V., Sannikov, D. G. & Sementsov, D. I. Anisotropy, gyrotropy and dispersion properties of the periodical thin-layer structure of magnetic-semiconductor. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 322, 3807–3816 (2010).

Landry, G. D. & Maldonado, T. A. Gaussian beam transmission and reflection from a general anisotropic multilayer structure. Appl. Opt. 35, 5870–5879 (1996).

Nobahar, D. & Akou, H. Distortion of a twisted beam passing through a plasma layer. Appl. Opt. 59, 6497–6504 (2020).

Visnovsky, S. Optics in Magnetic Multilayers and Nanostructures (Optical Science and Engineering) (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2006).

Yeh, P. Electromagnetic propagation in birefringent layered media. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 69, 742–756 (1979).

Luo, L., Tang, T., Shen, J., Li, C. & Yao, J. Nonlinear magneto optic spin Hall effect of transmitted light through a multilayer with graphene in terahertz region. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 484, 201–206 (2019).

Kahn, F. J., Pershan, P. S. & Remeika, J. P. Ultraviolet magneto-optical properties of single-crystal orthoferrites, garnets, and other ferric oxide compounds. Phys. Rev. 186, 891 (1969).

Ramakrishna, S. A. Physics of negative refractive index materials. Rep. Prog. Phys. 68, 449 (2005).

Tuz, V. R., Vidil, M. Y. & Prosvirnin, S. L. Polarization transformations by a magneto-photonic layered structure in the vicinity of a ferromagnetic resonance. J. Opt. 12, 095102 (2010).

Ghasemi, F. & Razi, S. Faraday rotator made of conjugated magneto active photonic crystal heterostructures. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 538, 168304 (2021).

Yin, C. P., Wang, T. B. & Wang, H. Z. Magneto-optical properties of one-dimensional conjugated magnetophotonic crystals heterojunctions. Eur. Phys. J. B 85, 104 (2012).

Saghirzadeh Darki, B., Zeidaabadi Nezhad, A. & Hossein Firouzeh, Z. Analysis and synthesis of one-dimensional magneto-photonic crystals using coupled mode theory. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 426, 163–172 (2017).

Royer, F. et al. Enhancement of both Faraday and Kerr effects with an all-dielectric grating based on a magneto-optical nanocomposite material. ACS Omega 5, 2886–2892 (2020).

Markovich, D. L., Andryieuski, A., Zalkovskij, M., Malureanu, R. & Lavrinenko, A. V. Metamaterial polarization converter analysis: Limits of performance. Appl. Phys. B 112, 143–152 (2013).

Huang, X. et al. Simultaneous realization of polarization conversion for reflected and transmitted waves with bi-functional metasurface. Sci. Rep. 12, 2368 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. A reflection-transmission multifunctional polarization conversion metasurface. IEEE T. Antenna Propag. 72, 5099–5109 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is based upon research funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) and Supreme Council of Science, Research and Technology (SCSRT) under project No.4022375.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. N. conceived the research idea, developed the research intentions, and performed the numerical simulations. D. N. and J. B. discussed the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nobahar, D., Barvestani, J. Tunable magneto-optical Faraday and polar Kerr rotations in a plasma-ferrite metamaterial. Sci Rep 15, 8132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92740-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92740-z