Abstract

The transition from foraging to plant cultivation represents the most important shift in the economic history of early Holocene societies. This process unfolded independently in different regions of the globe, resulting in varied plant assemblages, cultivation strategies, dietary practices, and landscape modifications. To investigate the drivers of this transition, we employed a machine-learning approach. Using Random Survival Forest, we analyze a comprehensive dataset of radiocarbon dates linked to the first adoption of domesticated plants, coupled with environmental predictors. Our findings indicate strong spatial autocorrelation in the timing of agricultural adoption, underscoring the role of diffusion and contact between regions. Region-specific bioclimatic factors emerged as influential: in the Americas, mean temperature and temperature seasonality were critical, while in Southwest Asia and Europe, seasonal variation in precipitation relative to temperature held greater importance. These results suggest that diffusion facilitated the spread of agricultural practices in a process shaped by local environmental conditions, as it was not possible to determine a set of universal drivers. Thus, the emergence of food production was influenced by a combination of local factors and cultural transmission, leaving the specific determinants for each region’s first transition an open question for further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The shift from foraging to plant cultivation and domestication represents the most important transition in the economic history of early Holocene societies. This transformation occurred independently across different regions of the world1,2,3, leading to the development of diverse assemblages of domesticated plants. The composition of these assemblages varied considerably, contributing uniquely to diets and landscape management practices depending on the region. For instance, while some areas—such as Europe and the Southwest Asia – adopted intensive cereal-based agriculture, others – such as the Neotropics – favored home gardening and agroforestry systems4,5.

A central, long-standing question remains: did the shift to plant cultivation, whether through the local domestication of plants or the adoption of non-native cultivars, arise from global driving forces, or were region-specific factors more influential? This debate has persisted since early studies on the origins of agriculture, with theories attributing the primary impetus to factors such as population pressure and diminishing returns6,7, as well as niche construction8. Alternatively, the emphasis on local environmental conditions has been proposed to explain regional transitions to cultivation, such as the influence of the Younger Dryas in the Near East9 and the early Holocene forest expansion in South America10.

In this study, we utilize survival analysis to model and predict the timing of initial transitions to food production on a global scale, incorporating archaeological data and environmental variables. Our analysis reveals strong spatial autocorrelation in the timing of these transitions, underscoring the substantial role of diffusion and interregional contact. When controlling for spatial lag, we observe different contributions from bioclimatic predictors depending on the specific region examined. For example, annual mean temperature and seasonality are key predictors in the Americas, whereas the temperatures during the wettest and driest quarters are most influential in the Near East and surrounding regions. We propose that these differences are linked to the distinct plant assemblages and the local biogeographic conditions that shaped their spread. In conclusion, our findings support the view that the global emergence of food production was driven not by a singular, universal cause, but by a range of local factors, further shaped by processes of contact and diffusion.

Overall chronology

Globally, the first centers of plant domestication emerged during the early Holocene. In the Americas, early evidence is found in southwestern Mesoamerica, where maize (Zea mays L.) was domesticated approximately 10,000 to 8,000 years before present (BP, calibrated years before 1950)11. Northwestern South America also stands out for the early domestication of crops such as squash (Cucurbita sp.), documented since the early Holocene5,10. The Llanos de Moxos region, in southwestern Amazonia, represents another early center, with manioc (Manihot sp.) and squash (Cucurbita sp.) occurring around 10,000 BP12.

In Africa, independent centers have been documented in the western part of the continent, where crops such as pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R.Br.), African rice (Oryza glaberrima Steud.), and fonio (Digitaria sp.) were domesticated after the African humid period, ca. 4,500 BP13. In eastern Africa, the available evidence indicates that sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) was domesticated in the eastern Sahel region ca. 6,000 BP14, while the earliest remains of other eastern African domesticates such as finger millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.) and teff (Eragrostis teff (Zucc.) Trotter) appear around 2,000 BP in the Horn of Africa15,16.

Eurasia’s Neolithic is marked by the domestication of staple cereals such as wheat (Triticum spp.) and barley (Hordeum spp.) within the Fertile Crescent around 10,000 to 8,000 BP. Although full domestication is associated with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) period, early indicators of storage and cultivation appear in Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) sites, which is the reason why these dates are included in this study2,17. In the Indian subcontinent, southern regions witnessed independent domestication of crops including millets (Panicum sp., Setaria sp.) and beans (Vigna sp.) around 5,000 BP2. East Asia saw two major centers: the Yellow River basin in northern China, where millets (Panicum sp., Setaria sp.) were cultivated potentially as early as the early Holocene, and the Yangtze basin in southern China, where rice (Oryza sp.) was domesticated by 10,000 to 8,000 BP18.

As for Oceania, in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, an independent domestication process involved the cultivation of bananas (Musa sp.) at approximately 7,000 BP19.

Following these early domestication events, the spread of agricultural practices varied regionally. In the Americas, the eastern lowlands of South America exhibit more recent dates for the presence of cultivars, often linked to migration and cultural diffusion during the mid to late Holocene. The spread of crops, particularly from the Amazon Basin, is closely associated with the Arawak and Tupi-Guarani expansions, to cite the most important ones20,21. In North America, the early adoption of maize in the Southwest contrasts with the mid-Holocene domestication of goosefoot (Chenopodium sp.) and sunflower (Helianthus sp.) in the eastern temperate forests. The spread of maize and other crops of Mesoamerican origin followed later22.

In Africa, a major vector for the dissemination of agriculture was the Bantu expansion, which began in West Africa around 8,000 BP and continued throughout sub-Saharan Africa into the late Holocene23.

The spread of the Neolithic crop package from the Fertile Crescent into Europe has been interpreted as a case of demic diffusion, marked by the westward expansion of farming24,25,26. Eastward diffusion into South Asia was delayed before reaching the Indus basin, potentially due to climatic challenges posed by monsoon-dominated regions27.

Finally, in East and Southeast Asia, the distribution of rice cultivation has been studied in the context of demic diffusion, highlighting the movement of agricultural practices and populations across these regions28,29,30.

Materials and methods

Data compilation

Data was compiled from published radiocarbon databases of global and continental coverage18,30,31,32,33,34. We selected dates acquired directly from plant remains of cultivated and domesticated species, or associated with them through context, stratum/level, or general site period information (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). In regions with limited evidence or preservation of plant macroremains, such as South America, South Asia or Africa, we also used dates derived from pollen and phytolith data. Additionally, we included dates not directly associated with archaeobotanical evidence, but which belonged to archaeological cultures known to have practiced agriculture (for example, dates associated with a Neolithic occupation in Europe, Bantu occupation in Africa or Tupi-Guarani - among many other agroforestry-practicing cultures - in lowland South America).

To conform to the spatial resolution of our environmental data and prioritize the date of first transition in each region, avoiding as much noise as possible, we retained only the earliest dates within a 50-kilometer radius. Our data set comprises a total of 1589 dates.

Dates associated with the transition to food production used in this study. Map created by the authors using R v4.4.2 (https://www.r-project.org/).

Environmental predictors

We utilized 17 bioclimatic variables and net primary production data derived from climate simulations based on the HadCM3 and HadAM3H models, accessed using the R package pastclim35,36. Because we focused on the Holocene epoch, when most of the transitions took place, and considering that the dates span from the early to the late Holocene, we averaged the values across time slices, each spanning 1,000 years, from 12,000 years before present (BP) to the present, retaining the average of the 12 slices for each bioclimatic variable in the analysis. Our edaphic predictors included 20 parameters for topsoil and subsoil characteristics, obtained from the Harmonized World Soil Database37.

Terrain-related variables included elevation and rugosity, sourced alongside the climatic data from pastclim. Additionally, we calculated the distance from major rivers and the coast using the Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database38, separating the distance from first, second and third-level rivers.

To enhance model parsimony and mitigate multicollinearity, we excluded predictors with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.9. After addressing collinearity, our final dataset comprised 36 predictors.

All raster data were projected to the WGS84 coordinate system and standardized to a resolution of 0.5 degrees, consistent with the original resolution of the bioclimatic dataset. Raster processing was conducted using R version 4.3.1 and QGIS version 3.34.

Spatial structure

Demic and cultural diffusion played an important role in the global transition to food production20,24,39. To account for this phenomenon, we explore spatial autocorrelation in the data using variation partitioning and distance-based Moran’s eigenvector maps (dbMEMs). We conducted variation partitioning to assess the proportion of variance influenced by spatial structuring40,41. This analysis broke down the total inertia into independent and shared fractions: the exclusive contribution of each explanatory dataset, the joint fractions due to intercorrelation, and the unexplained fraction. We also constructed dbMEMs using the distances based on the latitude and longitude of each site42,43. The median of the calibrated ages was used as the target variable.

Recognizing the pronounced spatial autocorrelation present in the target variable, we included latitude and longitude as predictors in a Random Forest model to capture nonlinear spatial dependencies44. This strategy helps to account for spatial patterns in the target variable and aligns with prior research suggesting that incorporating spatial information in the form of geographic coordinates can enhance the performance of tree-based machine learning models45. Additionally, using coordinates as model predictors enables global extrapolation, facilitating predictions beyond the original dataset coverage.

Random forest

We employ Random Forest to predict the time of transition to food production. Random Forest is a machine learning ensemble algorithm that excels at capturing complex relationships between predictors and the outcome without requiring strict prior specifications. This method is particularly suitable for our analysis due to its robustness against overfitting and its ability to handle non-normally distributed independent variables46.

For our study, we utilize a variant of Random Forest tailored for survival analysis known as Random Survival Forests (RSF)47. Survival analysis is a regression technique designed for modeling the time duration until an event takes place. It differs from conventional regression models by dealing with inherently positive time-to-event data48,49.

RSF adapts the traditional Random Forest framework to handle time-to-event data, where the event of interest is the transition to food production. This approach constructs multiple decision trees, each calculating a survival function representing the probability that the event time exceeds a given time point t.

The RSF model calculates the survival function using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, defined as:

where dj, h is the number of events and Yj, h is the number of individuals at time tj in terminal node h. The node splits in each tree are determined to maximize the difference in survival between nodes, enhancing the model’s predictive performance.

The dependent variable in our model is the date of transition to food production, measured from the earliest date in our dataset (12,700 BP). Our predictor matrix includes a comprehensive set of 36 bioclimatic, edaphic, and terrain variables, as previously described.

We implemented the Random Survival Forest model using the randomForestSRC package in R50. We tuned the model to minimize out-of-sample error, which was calculated using 80% of the data for model fitting (in-bag samples). The best model was retained with 500 trees, a terminal node size of 2, and 35 variables tried at each split.

To assess the performance of the Random Forest model, we utilized Harrell’s concordance index (C-index)51,52 of the out-of-bag (OOB) samples. The C-index measures the agreement between the observed survival outcomes and the predicted outcomes. Specifically, it evaluates whether observations with earlier dates are correctly predicted by the model as having a worse outcome (in terms of survival) than the observations with later dates. The prediction error is calculated as 1 - C, where a prediction error of 0.5 indicates that the model’s performance is no better than random chance.

Variable importance

We assessed variable importance using the Breiman-Cutler permutation importance method46. This method measures the importance of each variable by quantifying the increase in prediction error when the values of that variable are randomly shuffled within the out-of-bag samples.

Additionally, we estimated the individual feature contributions to the model using Shapley values, a concept derived from cooperative game theory53. Shapley values measure the marginal impact of each feature on the model’s prediction across all possible feature combinations. We calculated Shapley values using the R library fastshap54.

Results and discussion

Spatial autocorrelation

Variation partitioning showed significant effects of all sets of variables in the response (Supplementary Fig. S2). A notable portion of the variance related to terrain, bioclimatic, and soil factors overlapped with the spatial component, revealing significant linear spatial patterns among the environmental variables. Crucially, the spatial component alone accounted for 16% of the total inertia, highlighting the influence of cultural transmission or migration in the spread of plant cultivation, as anticipated. Nevertheless, the environmental variables account for a similar portion of the variability, which is not shared with the spatial component, pointing to the importance of local environmental processes in shaping the timing of the transition to plant cultivation55.

The final model, incorporating 33 dbMEM eigenvectors, achieved an adjusted R² of 0.64. The primary axis of variation closely replicates the distinction between regions exhibiting the earliest transition dates compared to those receiving the spread of these transitions. This pattern is particularly evident in contrasts such as Southwest Asia versus South Asia, and Northwest South America/Mesoamerica versus other regions of the American continent (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Random forest and variable importance

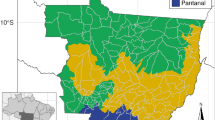

The Random Forest model achieved high accuracy on test data (0.83) based on the error of the OOB samples. The model accurately predicts the emergence of agriculture in different centers and its spread (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S4).

Predicted time of transition to food production based on the median survival results from the Random Survival Forest. Map created by the authors using R v4.4.2 (https://www.r-project.org/).

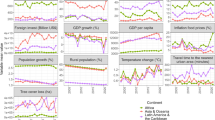

To understand the factors that drive this process, we primarily focus on the interpretation of Shapley values (Fig. 3), with permutation test results validating a similar order of variable importance (Supplementary Fig. S5). Notably, latitude and longitude emerged among the most critical features, highlighting pronounced spatial autocorrelation. Longitude’s importance reflects the early domestication dates in and around the Fertile Crescent, a center from which agriculture spread east and west, contrasting with the generally later transition in the western hemisphere (Fig. 2). A similar trend can be observed in Africa regarding latitude. In this case, the southwards expansion of Bantu-speaking populations from western Central Africa was a major driver of agricultural diffusion, with earlier transitions occurring in regions closer to the Sahel and progressively later adoptions further south. Although distance from rivers does not appear among the top features, this variable might have played a role in supplying habitats for the diffusion of cultivars such as rice in East Asia, where the Yangtze river would have offered the wetland margins of the early cultivation systems of this water-loving plant56. Distance from top-level rivers holds greater importance in the permutation test compared to Shapley values (Supplementary Fig. S5), which could tentatively be attributed to the role of diffusion.

Given that processes such as diffusion and migration are key drivers in the spread of plant domestication20,24,39, proximity to an established center of food production was expected (and confirmed) to increase the likelihood of transitioning to agriculture. While disentangling the effects of diffusion/migration from spatial autocorrelation in environmental variables can be challenging, variation partitioning demonstrates that not all variance explained by the spatial component overlaps with bioclimatic predictors (Supplementary Fig. S2). Shapley values further reveal the individual contributions of each variable. Excluding the spatial lag, the most influential environmental predictors were identified as the mean temperature of the wettest quarter, temperature seasonality, annual mean temperature, and the mean temperature of the driest quarter (Fig. 3).

To explore spatial patterns in the impact of different variables, we analyzed the spatial distribution of Shapley values, an approach which enables an assessment of how the relative contributions of variables change across global regions57,58 (Fig. 4).

Spatial distribution of the Shapley values for the four most important features (excluding geographical coordinates). Maps created by the authors using R v4.4.2 (https://www.r-project.org/).

The spatial pattern in the environmental variables is evident also from the dependence plots, showing that the highest contributing variables related to temperature, seasonal temperature and precipitation displayed interactions with longitude (Fig. 5). Specifically, the mean temperature of the wettest quarter greatly influenced early domestication dates in the Near East and Mediterranean (Fig. 4). These regions are characterized by low temperatures during the wettest quarter (rainy winters) and elevated temperatures during the driest quarter (dry summers). The spatial variation in these variables elucidates some of the observed diffusion patterns, namely the deceleration of agricultural spread from the Near East to South Asia. This shift involved crossing from a Mediterranean climate to a monsoon-influenced tropical climate, which contributed to delays in adapting the original plant package from the Near East27.

Temperature seasonality and annual mean temperature also interact with longitude (Fig. 5), and were critical predictors in the western hemisphere, explaining the transition gradient from Mesoamerica and Northwestern South America to other areas of the American continent. Regions with less seasonality and warmer climates saw earlier domestication. These areas then became the primary centers for the initial diffusion of domesticated species while further diffusion reflected challenges, especially in the adaptation of tropical domesticates, such as maize, to temperate zones. An alternative explanation is that less seasonal environments were associated with higher forager population densities in regions with high net primary productivity, as previously suggested59. If that is the case, such population pressures might have accelerated transitions to agriculture due to diminishing foraging returns, suggesting that forager population density could be a relevant but unexamined variable in our analysis. However, foraging population density – though previously identified as critical in the transition to farming60,61 – is partly predictable from bioclimatic variables59,62. Including it would introduce collinearity and is therefore best excluded from the analysis.

A notable conclusion is the contrast in plant domestication chronologies between the Americas and Southwest Asia, stemming from the photoperiodic needs of key domesticates. In the Americas, the main crops were short-day plants, which flowered as daylight shortened. Conversely, cereals in Southwest Asia were long-day plants, thriving through winter and flowering as daylight lengthened during dry summer months63. This differentiation helps explain the variable importance of climatic factors: in the Americas, temperature seasonality and mean temperature were predominant, whereas in Southwest Asia, interactions between temperature and precipitation held more significance. The combination of mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers created favorable conditions for wild cereals like wheat and barley, which composed the most important part of the Southwest Asian Neolithic crop package. Previous simulations incorporating bioclimatic factors and technological development replicated the rapid spread of cereal cultivation in the Near East, compared to the slower adoption of less energy-efficient American cultigens (except maize), delaying agriculture in the Americas60.

These differences underscore the gradient in adoption dates, suggesting that delays in domestication and spread were influenced by regional variations in temperature and precipitation seasonality in relation to the local plant package, a phenomenon previously discussed regarding the expansion of cereal crops into South Asia27. At the same time, it should be noticed that, unlike Southwest Asia, where diffusion occurred across regions with relatively similar bioclimatic conditions, the western hemisphere presents a more complex scenario, with distinct centers of development in diverse biomes, complicating the analysis of date gradients and feature importance at a continental scale. To that, we must add the lower diversity of domesticable species, and a slower transition influenced by cultural diffusion rather than demic diffusion, as highlighted by previous simulations focused on Eastern North America versus Europe64.

Similarly, the results are much more ambiguous for regions such as the African continent, where the effect of the bioclimatic variables is not as clear. This might be related to a different model of agricultural expansion, likely following a nonlinear trajectory65. Indeed, the expansion of agriculture in Africa occurred later and at a slower pace than in other areas such as Southwest Asia or the Americas. Recent studies indicate that plant cultivation in Africa was gradually incorporated into more complex models of subsistence, not necessarily representing the main source of food, but instead being part of a more holistic approach to subsistence that included the use of both wild and domestic plant and animal resources for long periods of time16,66,67,68,69. Such a complex introduction trajectory may hinder the model’s ability to identify the influence of bioclimatic variables in the expansion of agriculture, as the interaction between the environment and agricultural practices occurs within a more diverse and dynamic framework.

Finally, although soil properties were crucial for selecting species suitable for cultivation in arid environments55, they did not emerge as key predictors for the timing of initial food production transitions. It is likely that while edaphic factors influence agricultural practices in later stages, initial transitions were more dependent on broader bioclimatic conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings do not identify a set of variables that globally drive the transition to food-producing economies. Instead, our analysis highlights the significance of diffusion, supported by the observed spatial autocorrelation in the timing of agricultural adoption and the strong influence of spatial predictors. The spatial patterns evident from the Shapley values indicate that the bioclimatic factors influencing the timing of agricultural adoption differ by region. Specifically, in the Americas, factors related to temperature and temperature seasonality play a more prominent role, whereas in Southwest Asia precipitation relative to temperature emerges as more important.

This regional variability may be influenced by the types of plants domesticated in each area, such as the distinction between short- and long-day plants. Our model appears to have effectively captured these local bioclimatic influences alongside the overarching process of diffusion. However, while the model elucidates region-specific factors tied to plant availability, it does not point to any singular global determinant for the emergence of food production.

In summary, although our model accurately captures the factors driving the spread of food production across diverse bioclimatic conditions, the specific determinants at each center of origin require independent analysis. Local environmental shifts, such as changes in precipitation, land cover and other disruptions linked to the Younger Dryas and the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, may have independently triggered domestication processes3,70. This hypothesis necessitates separate investigation using distinct methodological approaches. Thus, while diffusion and regional environmental factors play essential roles, the precise factors driving agricultural development in each center of food production remain an open question for further investigation.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study and the code for reproducing the analysis are available in https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14823576.

References

Weiss, E. & Zohary, D. The neolithic Southwest Asian founder crops: Their biology and archaeobotany. Curr. Anthropol. 52, S237–S254 (2011).

Fuller, D. Q. Agricultural origins and frontiers in South Asia: A working synthesis. J. World Prehist. 20, 1–86 (2006).

Piperno, D. R. & Pearsall, D. M. The Origins of Agriculture in the Lowland Neotropics (Academic, 1998).

Fausto, C. & Neves, E. G. Was there ever a neolithic in the neotropics? Plant familiarisation and biodiversity in the Amazon. Antiquity 92, 1604–1618 (2018).

Iriarte, J. et al. The origins of Amazonian landscapes: plant cultivation, domestication and the spread of food production in tropical South America. Quat Sci. Rev. 248, 106582 (2020).

Cohen, M. N. The Food Crisis in Prehistory: Overpopulation and the Origins of Agriculture (Yale University Press, 1977).

Binford, L. R. On the origins of agriculture. in In Pursuit of the Past: Decoding the Archaeological Record (ed Binford, L. R.) 195–213 (University of California Press, Berkeley, (1983).

Smith, B. D. Niche construction and the behavioral context of plant and animal domestication. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues News Reviews. 16, 188–199 (2007).

Bar-Yosef, O. Climatic fluctuations and early farming in West and East Asia. Curr. Anthropol. 52, S175–S193 (2011).

Piperno, D. R. The origins of plant cultivation and domestication in the new world tropics patterns, process, and new developments. Curr. Anthropol. 52, (2011).

Kistler, L. et al. Multiproxy evidence highlights a complex evolutionary legacy of maize in South America. Science () 362, 1309 LP – 1313 (2018). (1979).

Lombardo, U. et al. Early holocene crop cultivation and landscape modification in Amazonia. Nature 581, 190–193 (2020).

Neumann, K. Development of plant food production in the West African savannas: archaeobotanical perspectives. in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History (Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.138. (2018).

Winchell, F. et al. On the origins and dissemination of domesticated Sorghum and Pearl millet across Africa and into India: a view from the Butana group of the Far Eastern Sahel. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 35, 483–505 (2018).

Manning, K. A Developmental History of West African Agriculture. West African Archaeology: New Developments, New perspectives / (British Archaeological Reports, 2010).

Ruiz-Giralt, A. et al. On the verge of domestication: Early use of C 4 plants in the Horn of Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120 (2023).

Arranz-Otaegui, A., Colledge, S., Zapata, L., Teira-Mayolini, L. C. & Ibáñez, J. J. Regional diversity on the timing for the initial appearance of cereal cultivation and domestication in southwest Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 14001 LP – 14006 (2016).

Stevens, C. J. & Fuller, D. Q. The spread of agriculture in Eastern Asia. Lang. Dyn. Change. 7, 152–186 (2017).

Denham, T. P. et al. Origins of agriculture at Kuk swamp in the highlands of new Guinea. Science (1979). 301, 189–193 (2003).

De Souza, J. G., Alcaina Mateos, J. & Madella, M. Archaeological expansions in tropical South America during the late holocene: Assessing the role of Demic diffusion. PLoS One. 15, e0232367 (2020).

de Gregorio, J., Noelli, F. S. & Madella, M. Reassessing the role of climate change in the Tupi expansion (South America, 5000–500 BP). J. R Soc. Interface. 18, 20210499 (2021).

Smith, B. D. General patterns of niche construction and the management of ‘wild’ plant and animal resources by small-scale pre-industrial societies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B: Biol. Sci. 366, 836–848 (2011).

Russell, T., Silva, F. & Steele, J. Modelling the spread of farming in the Bantu-speaking regions of Africa: An archaeology-based phylogeography. PLoS One. 9, e87854 (2014).

Pinhasi, R., Fort, J. & Ammerman, A. J. Tracing the origin and spread of agriculture in Europe. PLoS Biol. 3, e410 (2005).

Fort, J., Pujol, T. & Linden, M. Vander. Modelling the neolithic transition in the near East and Europe. Am. Antiq. 77, 203–219 (2012).

Silva, F. & Steele, J. New methods for reconstructing geographical effects on dispersal rates and routes from large-scale radiocarbon databases. J. Archaeol. Sci. 52, 609–620 (2014).

de Gregorio, J., Ruiz-Pérez, J., Lancelotti, C. & Madella, M. Environmental effects on the spread of the neolithic crop package to South Asia. PLoS One. 17, e0268482 (2022).

Silva, F. et al. Modelling the geographical origin of rice cultivation in Asia using the rice archaeological database. PLoS One. 10, e0137024 (2015).

Cobo, J. M., Fort, J. & Isern, N. The spread of domesticated rice in Eastern and southeastern Asia was mainly Demic. J. Archaeol. Sci. 101, 123–130 (2019).

Crema, E. R., Stevens, C. J. & Shoda, S. Bayesian analyses of direct radiocarbon dates reveal geographic variations in the rate of rice farming dispersal in prehistoric Japan. Sci. Adv. 8, (2022).

Bird, D. et al. p3k14c, a synthetic global database of archaeological radiocarbon dates. Sci. Data. 9, 27 (2022).

Manning, K., Colledge, S., Crema, E. R., Shennan, S. & Timpson, A. The cultural evolution of neolithic Europe. EUROEVOL dataset 1: Sites, phases and radiocarbon data. J. Open. Archaeol. Data. 5, e2 (2016).

Blake, M. et al. Ancient Maize Map, Version 1.1: An Online Database and Mapping Program for Studying the Archaeology of Maize in the Americas. (2012). http://en.ancientmaize.com/

Ziolkowski, M. S., Pazdur, M., Krzanowski, A. & Michczynski, A. Andes radiocarbon database for Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru. (1994).

Leonardi, M., Hallett, E. Y., Beyer, R., Krapp, M. & Manica, A. pastclim 1.2: an R package to easily access and use paleoclimatic reconstructions. Ecography (2023). (2023).

Beyer, R. M., Krapp, M. & Manica, A. High-resolution terrestrial climate, bioclimate and vegetation for the last 120,000 years. Sci. Data. 7, 236 (2020).

FAO/IIASA/ISRIC/ISSCAS/JRC. Harmonized World Soil Database v 1.2. Preprint at (2009). http://www.fao.org/soils-portal/soil-survey/soil-maps-and-databases/harmonized-world-soil-database-v12/en/

Wessel, P. & Smith, W. H. F. A global Self-consistent, hierarchical, High-resolution shoreline database. J. Geophys. Res. 101, 8741–8743 (1996).

Isern, N. & Fort, J. Assessing the importance of cultural diffusion in the Bantu spread into southeastern Africa. PLoS One. 14, 1–18 (2019).

Peres-Neto, P. R., Legendre, P., Dray, S. & Borcard, D. Variation partitioning of species data matrices: Estimation and comparison of fractions. Ecology 87, 2614–2625 (2006).

Blanchet, F. G., Legendre, P. & Borcard, D. Forward selection of explanatory variables. Ecology 89, 2623–2632 (2008).

Legendre, P., Borcard, D. & Roberts, D. W. Variation partitioning involving orthogonal Spatial eigenfunction submodels. Ecology 93, 1234–1240 (2012).

Borcard, D. & Legendre, P. All-scale Spatial analysis of ecological data by means of principal coordinates of neighbour matrices. Ecol. Modell. 153, 51–68 (2002).

Viana, D. S., Keil, P. & Jeliazkov, A. Disentangling Spatial and environmental effects: flexible methods for community ecology and macroecology. Ecosphere 13, e4028 (2022).

Li, Z. Extracting spatial effects from machine learning model using local interpretation method: an example of SHAP and XGBoost. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 96, 101845 (2022).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Ishwaran, H., Kogalur, U. B., Blackstone, E. H. & Lauer, M. S. Random survival forests. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2 (2008).

Cox, D. R. & Oakes, D. Analysis of Survival Data (Chapman and Hall, 1984).

Klein, J. P. & Moeschberger, M. L. Survival Analysis (Springer New York, 1997). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2728-9

Ishwaran, H. & Kogalur, U. B. Fast Unified Random Forests for Survival, Regression, and Classification (RF-SRC), R package version 3.2.0. Preprint at (2023).

Harrell, F. E., Califf, R. M., Pryor, D. B., Lee, K. L. & Rosati, R. A. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA 247, 2543–2546 (1982).

Harrell, F. E., Lee, K. L. & Mark, D. B. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat. Med. 15, 361–387 (1996).

Shapley, L. S. 17. A value for n-Person games. in Contributions To the Theory of Games (AM-28), Volume II 307–318 (Princeton University Press, doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400881970-018. (1953).

Greenwell, B. fastshap: Fast approximate shapley values. Preprint at (2024).

Ruiz-Giralt, A., Biagetti, S., Madella, M. & Lancelotti, C. Small-scale farming in drylands: New models for resilient practices of millet and sorghum cultivation. PLoS One. 18, e0268120 (2023).

Liu, X., Fuller, D. Q. & Jones, M. Early agriculture in China. in The Cambridge World History 310–334. Cambridge University Press (2015). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511978807.013

Wang, N. et al. On the use of explainable AI for susceptibility modeling: examining the Spatial pattern of SHAP values. Geosci. Front. 15, 101800 (2024).

Wadoux, A. & Molnar, C. Beyond prediction: methods for interpreting complex models of soil variation. Preprint At. https://doi.org/10.31223/X5G62K (2021).

Zhu, D., Galbraith, E. D., Reyes-García, V. & Ciais, P. Global hunter-gatherer population densities constrained by influence of seasonality on diet composition. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1536–1545 (2021).

Wirtz, K. W. & Lemmen, C. A global dynamic model for the neolithic transition. Clim. Change. 59, 333–367 (2003).

Lemmen, C. & Malthusian Assumptions Boserupian response in transition to agriculture models. in Ester Boserup’s Legacy on Sustainability 87–97 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8678-2_6 (2014).

Tallavaara, M., Eronen, J. T. & Luoto, M. Productivity, biodiversity, and pathogens influence the global hunter-gatherer population density. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, 1232–1237 (2018).

Jones, M. K. & Lister, D. L. The domestication of the seasons: The exploitation of variations in crop seasonality responses by later prehistoric farmers. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, (2022).

Lemmen, C. Mechanisms shaping the transition to farming in Europe and the North American woodland. Archaeol. Ethnology Anthropol. Eurasia. 41, 48–58 (2013).

Lancelotti, C. et al. Resilience of small-scale societies’ livelihoods: A framework for studying the transition from food gathering to food production. Ecol. Soc. 21, art8 (2016).

Madella, M., García-Granero, J. J., Out, W. A., Ryan, P. & Usai, D. Microbotanical evidence of domestic cereals in Africa 7000 years ago. PLoS One. 9, e110177 (2014).

Lucarini, G., Radini, A., Barton, H. & Barker, G. The exploitation of wild plants in neolithic North Africa. Use-wear and residue analysis on non-knapped stone tools from the Haua Fteah cave, Cyrenaica, Libya. Quatern. Int. 410, 77–92 (2016).

Winchell, F., Stevens, C. J., Murphy, C., Champion, L. & Fuller DorianQ. Evidence for Sorghum domestication in fourth millennium BC Eastern Sudan: Spikelet morphology from ceramic impressions of the Butana group. Curr. Anthropol. 58, 673–683 (2017).

Le Moyne, C. et al. Ecological flexibility and adaptation to past climate change in the middle nile Valley: A multiproxy investigation of dietary shifts between the neolithic and Kerma periods at Kadruka 1 and Kadruka 21. PLoS One. 18, e0280347 (2023).

Pearsall, D. M. & Stahl, P. W. The Origins and Spread of Early Agriculture and Domestication: Environmental and Cultural Considerations. in The SAGE Handbook of Environmental Change: Volume 2 328–354 (SAGE Publications Ltd, 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom (2012). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446253052.n39

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G.S. and J.R.P. conceptualized and designed the study. All authors contributed to data collection. J.G.S. developed the software code, performed the data analysis, and prepared the initial manuscript draft. All authors provided critical feedback, contributed to revising the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gregorio de Souza, J., Ruiz-Pérez, J., Ruiz-Giralt, A. et al. Environmental constraints and diffusion shaped the global transition to food production. Sci Rep 15, 8301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92782-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92782-3