Abstract

A great deal of evidence has accumulated suggesting an important role of mucosal immunity not only in preventing COVID-19 but also in the pathogenesis of this infection. The aim of the study was to evaluate the levels of secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) in different compartments of the upper respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients in relation to the severity of the disease and treatment with a bacteria-based immunomodulating agent (Immunovac VP4). The titers of sIgA were determined by ELISA in nasal epithelial swabs, pharyngeal swabs, and salivary gland secretions at baseline and on days 14 and 30 of treatment. The levels of nasal, pharyngeal and salivary sIgA were significantly lower in more severe patients (subgroup A) than in less severe patients (subgroup B), p < 0.01. In subgroup A, the patients who received Immunovac VP4 had higher pharyngeal sIgA levels in convalescent period than those who did not receive the therapy p < 0.05. In subgroup B patients, an increase in immunoglobulin levels was observed from baseline to day 14 of treatment whether they received the add-on therapy or not, p < 0.01. On day 30 of treatment, the sIgA levels in the standard treatment group, however, decreased, while the patients receiving the immunomodulating agent maintained high sIgA levels, p < 0.05. Oxygen saturation significantly increased by day 14 in both groups, p < 0.001. However, it was higher in the Immunovac VP4 group than in the standard treatment group, p < 0.01. Thus, addition of a bacterial lysate-based immunomodulating agent to the treatment regimen for moderate-to-severe COVID-19 induces the production of pharyngeal and salivary sIgA. SIgA production is inversely correlated to CRP levels and percentage of lung involvement on CT scan and is directly correlated to SpO2 levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 is a droplet-borne disease. Respiratory mucosal immunity provides the first barrier to virus invasion and thus plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of this infection. Since the infection first begins on upper respiratory tract mucosa, the induction of mucosal immunity with intranasal therapeutic vaccines has become one of several promising strategies for both preventing particular infections (e.g. COVID-19) and treating them1. Some bacterial lysate-based agents are considered therapeutic vaccines because they induce a specific humoral immune response to particular vaccine antigens as well as non-specific immune responses, which was demonstrated in numerous clinical trials2,3,4. These agents have been shown to decrease the risk of recurrent respiratory infections in children and adults, reduce the need for antibacterial therapy in patients with chronic bronchopulmonary disorders and exhibit a number of other clinical effects. To date, a number of papers have been published on the use of bacterial lysates in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma5,6,7,8.

Despite ongoing research of the mechanisms of mucosal immunity in viral infections, in particular COVID-19, the use of immunobiological medications during active inflammation as an immunotherapeutic approach has not been fully investigated. Little is known about the immunological and clinical effectiveness of these agents administered via different routes. For instance, Immunovac VP4 has been shown to trigger different morphological and functional changes in different compartments of the immune system after being administered through different routes9. Previously, we investigated the effects of Immunovac VP4 on sIgA levels in nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) when combined routes of administration were used (nasal/oral and nasal/subcutaneous)10,11.

Secretory immunoglobulin A is the main antibody class found on mucosal surfaces and produced by local plasma cells, primarily as an IgA dimer. It confers protection against various pathogens, including viruses, which is mediated by its neutralizing properties as well as its ability to prevent adhesion of pathogens to the mucosal surfaces and to opsonize pathogenic microorganisms, thus hindering their penetration into epithelial cells12.

SIgA, also known as “mucosal Immunoglobulin”, has been under keen interest throughout the viral infection cycle. Its importance lies because IgA is predominant mucosal antibody and SARS family viruses primarily infect the mucosal surfaces of human respiratory tract. Preliminary studies have demonstrated high secretory levels of specific neutralizing sIgA in adults with acute COVID-1913,14. Therefore, IgA can be considered a diagnostic and prognostic marker and an active infection biomarker for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Along with molecular analyses, serological tests, including IgA detection tests, are gaining ground in application as an early detectable marker and as a minimally invasive detection strategy15.

The observed limitations in the efficacy of currently authorized COVID-19 vaccines in inducing effective mucosal immune responses remind us of the limitations of systemic vaccination in promoting protective mucosal immunity. This resurgence of interest has motivated the development of vaccine platforms capable of enhancing mucosal responses, specifically the sIgA response, and the development of IgA-based therapeutics16.

Study objective

To evaluate the levels of secretory immunoglobulin A in different compartments of the upper respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients in relation to the severity of their disease and treatment with a bacteria-based immunomodulating agent (Immunovac VP4).

Materials

Clinical study design

It was a non-randomized controlled study, which was conducted in a tertiary hospital for COVID-19 patients (Moscow, Russian Federation). The selection of patients was done following screening assessments and physical examination and was based on the inclusion and non-inclusion criteria as well as the information in the Indications and Contraindications sections of the Immunovac VP4 Product Information Leaflet. The patients were followed up for 30 days. All treatment information, clinical findings and study tests data were reported using medical records (individual patient documentation).

Legal and ethical conduct of the study

Treatment was carried out in accordance with the Provisional Clinical Guidelines “Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19)” developed by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation and clause 20 “Voluntary Informed Consent to Medical Intervention and Refusal of Medical Intervention” (Federal Law No. 323-ФЗ, dated November 1, 2011 “On Fundamental Healthcare Principles in the Russian Federation” (as amended on April 3, 2017). Study Protocol No. 8 was approved on November 26, 2020 by the local Ethics Committee at the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution I.I. Mechnikov Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera (Moscow). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association “Ethical Principles for Biomedical Investigations Involving People”, the International Council for Harmonization’s Good Clinical Practice guideline and Russian regulatory requirements. Prior to inclusion in the study, all study subjects provided written informed consent.

Inclusion Criteria: age 18 to 60 years, admission to hospital, positive results with SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in nasal swabs, CT signs of lung damage such as ground-glass opacities and areas of consolidation consistent with grade 2 of lung injury as assessed by CT scan (25–50% lung involvement), and signed and dated informed consent form.

Non-inclusion criteria (patients were not included in the study if they met any of these criteria): lung abscess, pleural empyema, active tuberculosis; severe birth defects or serious chronic disorders, such as pulmonary, liver, renal, cardiovascular or neurological disorders; a history of mental or endocrine disorders or neoplasms; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis B or C infections; use of immunoglobulins or blood transfusion within the last three months prior to the start of the study; long use (more than 14 days) of immunosuppressive drugs or other immunomodulatory drugs within six months prior to the start of the study; any known or suspected immunosuppressive, immunodeficiency or autoimmune disorder; any vaccination within one month prior to the start of the study; acute respiratory infections within one month prior to the start of the study; pregnancy or lactation; simultaneous participation in another clinical study; or the patient’s inability to comply with the study protocol requirements (as judged by the investigator).

Patients

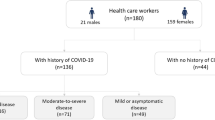

Overall, 105 patients, aged 18 to 60, with confirmed moderate-to-severe COVID-19 were included in the study between November 30, 2020 and May 30, 2021. The diagnosis was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), clinical data and CT findings. All patients had CT signs of lung damage such as ground-glass opacities and areas of consolidation consistent with grade 2 of lung injury as assessed by CT scan (25–50% lung involvement). The COVID-19 patients included in the study met all the inclusion criteria and did not meet the exclusion criteria.

All patients received background therapy which was selected according to the severity of their disease as recommended by the clinical guidelines developed by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. It included Favipiravir 200 mg (standard regimen, depending on bodyweight: 1.6–1.8 g on day 1 followed by 600–800 mg twice a day on days 2 to 10), enoxaparin 0.4 mg/day, subcutaneously, dexamethasone 8–12 mg/day, and tocilizumab 400 mg/day (for patients with CRP > 60 mg/L).

At the start of the study all patients were randomized into two groups: Group 1 (control group, n = 41) consisted of patients who received only standard treatment in accordance with the clinical guidelines developed by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation; and Group 2 (main group, n = 64) was made up of patients who received standard treatment combined with an 11-day treatment course of a bacterial lysate-based therapeutic agent (Immunovac VP4), which was started on day 1 of hospitalization.

Group 1 consisted of 27 males and 14 females, the median age of the patients was 42 (33; 54) years. Group 2 consisted of 43 males and 22 females, the median age of the patients was 42 (37; 45) years. Both groups were matched by age (p = 0.79), gender (p = 0.33) and the number of days between the onset of disease and hospitalization (5 [4; 8] days in Group 1 and 5 [3; 7] days in Group 2, p = 0,63). The patients in both groups were also matched by body mass index, area of impaired lung parenchyma, and laboratory findings.

Biological samples from different compartments of the upper respiratory tract were also collected from healthy non-vaccinated health care providers with no history of COVID-19 (n = 10). They were divided into aliquots and used as the internal standard in laboratory tests.

Since sIgA levels in the upper respiratory tract correlate with the severity of COVID-1917,18, the study subjects were further divided into two subgroups in order to better understand the effects of Immunovac VP4: patients with a more severe disease (subgroup A) and patients with a less severe disease (subgroup B). This division was conducted based on a cluster analysis. The cluster analysis was carried out using the following factors: oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, CRP as an indicator of the intensity of inflammatory and destructive processes, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) as an indicator of degree of heart damage. The results of the cluster analysis are shown in Fig. 1. The silhouette score, a characteristic of the quality of clusters, was 0.65, which indicated that our clusters were well-defined4.

Compared to cluster 2, cluster 1 had higher levels of CRP (20.1 [10.9; 43.2] mg/L vs. 2.2 [0.3; 10.7] mg/L, p < 0.001) and AST (32.9 [28.2; 44.9] U/L vs. 26.2 [20; 34.9] U/L, p = 0.003) and lower SpO2 levels (94 [94; 95]% vs. 96 [96; 96]%, p < 0.001). Therefore, the patients in cluster 1 were regarded as clinically more severe, and the patients in cluster 2 as clinically less severe. There was no difference between the subgroups in the disease duration prior to hospitalization (6 [3.5; 7.5] days in the group of more severe patients and 5 [4; 8] days in the group of less severe patients, p = 0.83) or patient age (45 [38; 51] years old and 43 [37.2; 47.0] years old, respectively, p = 0.47). The sub group of more severe patients had a slightly higher proportion of males than the subgroup of less severe patients (80% [25/31] vs. 60% [45/74], respectively, p = 0.08). The duration of fever was similar in the study subgroups (1 [1; 5] day in the group of more severe patients and 1 [0; 4] day in the group of less severe patients, p = 0.22), while the duration of hospital stay was significantly longer in the subgroup of more severe patients compared to that in the subgroup of less severe patients (12 [7.5; 16.5) days vs.7 (4; 11.8) days, respectively, p = 0.01).

Bacterial lysate-based therapeutic agent

Immunovac VP4 (Certificate of Marketing Authorization No. ЛCP-001294/10 issued on February 24, 2010) belongs to a novel class of bacterial lysate-based therapeutic agents, so called “therapeutic vaccines”. This agent is manufactured by Scientific and Production Association Microgen, a federal state unitary enterprise (Ufa, Russia). The vaccine exhibits protective activity against the microorganisms included in its composition and provides a pronounced immunomodulatory effect with considerable potential to correct immune defects. A combination of these properties ensures a high therapeutic and preventive activity of this product19. Immunovac VP4 includes the antigens of Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus vulgaris and Escherichia coli (4 mg). Using non-aggressive methods for treatment of microbial biomass made it possible to mostly maintain the native structure of the antigens and include protein-associated lipopolysaccharides isolated from К. pneumoniae, P. vulgaris and E. coli, proteoglycan isolated from K. pneumoniae, as well as teichoic acids derived from S. aureus and protein and other polysaccharide antigens of S. aureus. The spectrum of antimicrobial activity of Immunovac VP4 against various opportunistic bacteria, including Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, was expanded not by increasing the number of vaccine components but by incorporating the antigens isolated from specifically selected highly immunogenic strains with weak sensitizing properties, which had intra- and inter-species antigens as well as immunostimulatory antigens. This considerably simplified the manufacturing process for this vaccine and increased its therapeutic effectiveness. Immunovac VP4 does not contain any preservatives or stabilizing additives. It is available as a lyophilized powder in ampoules and vials (see Product Information Leaflet for Immunovac VP4, a multi-component vaccine based on antigens of opportunistic microorganisms, approved by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation on September 18, 1996).

Pharmacological properties

It is a bacteria-based immunostimulant. Its mechanism of action is due to the activation of the key effectors of innate and adaptive immunity. This agent enhances the phagocytic activity of macrophages, optimizes cell counts and functional activity of lymphocyte subsets (CD3, CEM, CD8, CD16, and CD72), programs CD4 T-cells to proliferate and differentiate into Th1 cells, stimulates the production of IFN-γ and IFN-α, and improves the production of immunoglobulin isotypes by inhibiting IgE synthesis and inducing IgG, IgA, and sIgA synthesis20,21,22. It induces the production of antibodies to four opportunistic microorganisms whose antigens are included in the composition. It also contains antigens that can induce broad cross-protection against other pathogens (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and others).

The technical result of the proposed invention consists in disclosing the mechanism of the protective action of a multicomponent vaccine against bacterial and viral pathogens in oral and subcutaneous immunization methods by activating Toll-like receptors TLRs 2, 4 and 9, which confirms the presence in the multicomponent vaccine of pattern-associated molecular structures of microorganisms (peptidoglycan, teichoic acid, lipopolysaccharide, bacterial DNA), leading to the expression of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IFNγ, TNFα) and the formation of adaptive immunity, manifested in the production of specific IgG antibodies to antigens included in the vaccine. As a result of activation of effectors of innate and adaptive immunity, the multicomponent vaccine protects from bacterial and viral infection and explains the therapeutic and prophylactic effect of its use in clinical practice.

The consequence of activation of innate and adaptive immunity with subcutaneous and oral administration of the multicomponent vaccine was protection of experimental animals from infection with bacterial strains, the antigens of which were part of Immunovac VP-4. Protective activity during infection of experimental animals 24 h after immunization was considered as a consequence of activation of innate immunity, 5–8 days after immunization—as activation of adaptive immunity. With activation of adaptive immunity, protective activity was higher than with activation of innate immunity. Non-specific protection (innate immunity) from viral infection 24 h after subcutaneous or oral immunization with the multicomponent vaccine was demonstrated during infection with influenza virus and herpes virus with the subcutaneous method of immunization [Russian patent 2022 under IPC A61K38/00, RU2786222C1].

In terms of clinical outcomes, treatment with this drug reduces the rate of acute infections, duration of infection, severity of symptoms, and risk of exacerbation of chronic diseases.

Indications for immunovac VP4

Children older than 15 years of age and adults: chronic recurrent inflammatory respiratory diseases (acute phase [5 to 7 days after the start of background treatment], remission, and periods of increased number of respiratory infection cases prior to respiratory infection seasons); allergic disorders, including mixed-type asthma, infection- and allergy-induced asthma, and atopic dermatitis (in combination with background treatment during remission or after exacerbation); prevention of respiratory infections in individuals who have frequent acute respiratory disease events (more than 4 events a year) (periods of increased number of cases prior to respiratory infection seasons).

Preparing of Immunovac VP4 solution: Immediately prior to use, 4 mL of solvent (0.9% sodium chloride for injection or boiled water brought to 18–25 °C) is added to the vial with a syringe, and the contents is mixed. The dilution time should not exceed 2 min. The ready solution can be stored at + 2–8 °C for 3 days and can be used if it does not show any signs of cloudiness.

Regimens and doses

Regimen 1 (nasal and subcutaneous administration) (n = 31)

When prepared, the drug solution was administered at a dose of 2 drops (1.0 mg) in each nostril daily and then subcutaneously every other day in the following amounts: 0.05 ml (0.5 mg) on day 1 of hospital stay, 0.1 ml (1.0 mg) on day 3, 0.2 ml (2.0 mg) on day 5, 0.2 ml (2.0 mg) on day 7, 0.3 ml (3.0 mg) on day 9, and 0.3 ml (3.0 mg) on day 11.

Regimen 2 (nasal and oral administration) (n = 33)

When prepared, Immunovac VP4 solution was administered orally at a dose of 2 ml (20.0 mg) followed by 2 drops (1.0 mg) in each nostril daily from day 1 to day 10 of hospital stay.

Although the administration regimens were different, the patients were not divided into groups by administration regiment considering similar kinetics of sIgA production in the upper airways and similar clinical effects of this immunotherapeutic agent in COVID-19 patients, shown by other studies10,17.

Methods

For all patients, clinical data, concurrent disorders, symptoms of the underlying disease, physical examination findings, and results of laboratory tests (complete blood count, C-reactive protein, and blood coagulation profile) and other investigations (chest computed tomography, SpO2) were assessed. The severity of respiratory failure was defined by the blood oxygen saturation level measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2). Pulse oximetry was performed using a pulse oximeter (series MD300C). Chest computed tomography (CT) was performed on a spiral CT scanner Aquilion TSX-101A (Toshiba Medical Systems, slice thickness 1 mm, pitch 1.5) on admission and after 10 days of treatment.

Levels of sIgA in all biological fluids were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Vector Best, Russian Federation). Plates were read using a Multiskan Ascent ELISA microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, Finland). Levels of immunoglobulins were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay based on a two-step sandwich enzyme immunoassay using monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against the secretory component linked to alpha chain of IgA. Standards with known concentrations of sIgA and the samples were added to the wells of a plate coated with an anti-sIgA mAb. The plate was then incubated according to the test kit instructions. The intensity of developing color is proportional to the concentration of sIgA in the sample. The concentration of sIgA was calculated using the standard curve and the measured optical density values.

Sampling

In study groups 1 and 2, samples were taken from different compartments of the upper respiratory tract: nasal mucosal epithelial scrapings, pharyngeal epithelial scrapings, and salivary gland secretions. Saliva was collected early in the morning before patients brushed their teeth and had a meal. Saliva was collected passively under supervision of a physician without any forceful coughing23,24,25. Sampling was performed in three steps: on study day 1 before study treatment was administered, on study day 14, and subsequently 30 days after the start of treatment.

Cytobrush sampling was performed in all patients to determine protein levels in nasopharyngeal secretions. Samples were collected using a type D brush (Yunona, Russian Federation) into three Eppendorf tubes with sodium chloride solution. The tubes were centrifuged at 2,000 g for about 5 min to sediment the epithelial cells and then refrigerated at + 2–4 °C until shipment to the laboratory, where the samples were examined within 24 h of collection.

These tests were performed using certified equipment provided by the Research Equipment Sharing Center of the I.I. Mechnikov Research Institute of Vaccines and Sera.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics for quantitative variables included median and interquartile range, Me [Q1-Q3]. Comparison of quantitative variables in two independent groups was done using the Mann—Whitney’s test.

The cluster analysis was done using the k-means method with the silhouette score applied to determine the quality of clusters. The correlation analysis was performed using the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, and the robust linear regression analysis was carried out to calculate a regression line and construct a 95% confidence interval (CI) for its slope26.

A linear mixed-effects model (LMEM) was used to evaluate the changes in sIgA levels. The relationship between the changes in sIgA levels and the severity of a patient’s condition on admission was evaluated, with time, severity of condition and their interaction (time × severity) being fixed effects, and patients random effects. Another analysis focused on the relationship between the changes in sIgA levels and the study subgroup, which was studied separately for more severe and less severe patients. In this analysis time, study subgroup and their interaction (time × study subgroup) were fixed effects, and patients were random effects. Linear mixed-effects models were estimated using in the lme4 package. Each model’s fit (residual normality and homoscedasticity) was checked using the DHARMA package27. When the model fit was poor, another LMEM was fit using the robust estimation method in the robustlmm package (RobustLMEM)28. Satterthwaite’s approximation was used to calculate the degrees of freedom for the resulting models. Marginal R-squared (R2m, only fixed effects) and conditional R-squared (R2c, fixed and random effects) were generated for each model29. Post-hoc tests were performed by estimating the corresponding contrasts in the LMEM using the lmerTest package30.

The level of statistically significant differences was defined as p ≤ 0.05. The calculations and graphics were carried out using the statistical programming environment R (v.3.6, license GNU GPL2).

Study results

Analysis of the baseline data of all the study subjects revealed a significant inverse correlation between nasal sIgA and CRP (ρ = − 0.29 [95% CI − 0.48 to − 0.07], p = 0.01), AST (ρ = − 0.30 [95% CI − 0.49 to − 0.09], p = 0.007) and area of lung involvement on CT scan (ρ = − 0.23 [95% CI − 0,44 to − 0.005], p = 0.045) (Fig. 2a and b).

There was also an inverse correlation between pharyngeal sIgA and CRP levels (ρ = − 0.34 [95% CI − 0.52 to − 0.12], p = 0.003), and a direct correlation between salivary sIgA and SpO2 levels (ρ = 0.25 [95% CI 0.02 to 0.45], p = 0.03) (Fig. 3a and b).

The relationship (a) between pharyngeal sIgA and CRP levels on admission and (b) between salivary sIgA and SpO2 levels on admission. Note: The regression line was calculated and a 95% confidence interval for its slope was constructed by robust linear regression analysis. This analysis showed that patients with higher sIgA levels had lower CRP levels, smaller areas of lung involvement on CT scan and higher SpO2 levels.

These data are also consistent with the results of the analysis of the correlation between sIgA levels and the severity of disease at the time of admission. The cluster analysis revealed that nasal, pharyngeal, and salivary sIgA levels were significantly lower in subgroup A (more severe patients) than in subgroup B (less severe patients): 47.1 (17.6; 102.9) µg/L vs. 97.2 (60; 168) µg/L (p = 0.02); 0.8 (0.3; 3.1) µg/L vs. 6.5 (1.2; 24) µg/L (p = 0.007), and 90.5 (32.9; 185.4) µg/L vs. 210.6 (144; 354.8) µg/L (p = 0.007), respectively (Fig. 4).

These data suggest that there is a relationship between sIgA levels and the severity of COVID-19. Additionally, they show that SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers different responses in different aggregates of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

The changes in sIgA levels were assessed in relation to the severity of disease on admission and the treatment group at three time points (at baseline and on study days 14 and 30) using robust linear mixed-effects models (RLMEM) (Table 1).

Comparison of the changes in the sIgA levels in nasopharyngeal scrapings did not show any difference between the groups of patients who received standard treatment and those who received Immunovac VP4 as an add-on agent. In the subgroup of patients with a less severe disease, nasal sIgA levels at baseline and on days 14 and 30 were 100 (61; 168) µg/L, 59 (24; 114) µg/L, and 48 (20; 102) µg/L, respectively, in the control group and 91 (56; 153) µg/L, 48 (18; 116) µg/L, and 56 (11; 107) µg/L, respectively, in the group of subjects who additionally received the bacterial lysate-based immunostimulating agent. In the subgroup of patients with a more severe disease, these levels were 49 (46; 99) µg/L, 52 (16; 89) µg/L, 17 (11; 30) µg/L, respectively, and 31 (14; 99) µg/L, 47 (22; 119) µg/L, and 68 (19; 135) µg/L, respectively.

However, there were differences in the changes in oropharyngeal levels of sIgA. Analysis of day 30 pharyngeal sIgA levels in the subgroup of patients with less severe COVID-19 revealed a significant difference between the two study groups (p = 0.04). In the control group pharyngeal sIgA levels remained stable throughout the observation period, while in the main (Immunovac VP4) group they showed a significant increase by day 30 of treatment compared to the baseline levels (from 5.4 [0.7; 18.2] µg/L to 18.7 (5.2; 79.6) µg/L, p = 0.003) and to the day 14 levels (from 5.8 [1.9; 14.1] and 18.7 (5.2; 79.6) µg/L, p = 0.004) (Fig. 5). In the subgroup of patients with less severe COVID-19, day 30 levels of pharyngeal sIgA were significantly higher in the patients receiving Immunovac VP4 than in the controls: 18.7 (5.2; 79.6) µg/L vs. 2.9 (1.2; 29.4) µg/L, p = 0.05.

In the subgroup of patients with more severe COVID-19, pharyngeal sIgA levels showed the following kinetics: on day 14 of treatment similar changes were seen in the two study groups (p = 0.01), but on day 30 these changes were inverse (p = 0.05) (Fig. 6). On day 14 pharyngeal sIgA levels, which were initially lower compared to the subgroup of less severe patients, showed a significant increase, regardless of the treatment group: from 1.5 (0.3; 5.9) to 63.4 (17.8; 101.2) µg/L in the control group (p < 0.001) and from 0.7 (0.3; 3.1) to 61.1 (24.1; 111.6) µg/L in the Immunovac VP4 group (p = 0.005). After 30 days of treatment, pharyngeal sIgA levels decreased in the control group (from 63.4 [17.8; 101.2] to 11.3 [9.1; 14] µg/L, p < 0.001), while in the main group they remained similar to the day 14 levels and were higher compared to the baseline levels (87.6 [7.5; 118.6) µg/L vs. 0.7 [0.3; 3.1] µg/L, p = 0.001) and to the levels in the control group (87.6 [7.5; 118.6) µg/L vs. 11.3 [9.1; 14] µg/L, p = 0.007).

Analysis of salivary sIgA levels in patients with less severe COVID-19 revealed similar changes in this parameter on day 14 of treatment (p = 0.04) and inverse changes on day 30 (p = 0.03) in the two study groups (Fig. 7). In both study groups, the patients with a less severe disease showed a significant reduction in salivary sIgA levels from baseline to study day 14: from 236.4 (143.7; 493.2) to 154.2 (105; 200) µg/L, p = 0.04 in the control group and from 181 (144.4; 256.3) to 139.8 (95.5; 205.6) µg/L in the Immunovac VP4 group (p = 0.04). On day 30, in the control group salivary sIgA levels did not show any significant changes compared to baseline (158.3 [117; 198.8] µg/L vs. 236.4 [143.7; 493.2] µg/L, p = 0.05). In the Immunovac VP4, the day 30 levels of salivary sIgA showed a significant increase compared to the day 14 levels (from 139.8 [95.5; 205.6] µg/L to 208.5 [124.1; 403.6] µg/L, p = 0.003) and to the levels in the control group (208.5 [124.1; 403.6] µg/L vs.158.3 [117; 198.8] µg/L, p = 0.04) (Fig. 8).

In the subgroup of patients with a more severe disease, salivary sIgA levels gradually increased and on day 30 were significantly higher than at baseline: 199.3 (165; 226.6) µg/L vs. 73.6 (30.5; 177.3) µg/L, p = 0.05 in the control group and 237.2 (186.3; 303.2) µg/L vs. 119.6 (56.2; 185.4) µg/L, p = 0.001) in the Immunovac VP4 group (Fig. 8).

Analysis of SpO2 levels in the subgroup of patients with less severe COVID-19 on admission revealed some changes over time both in the control and main groups, i.e. there was a significant increase from baseline to day 14: from 96 (95; 96)% to 98 (96.5; 99)%, p < 0.001 and from 96 (96; 96)% to 98 (97.5; 99)%, p < 0.001, respectively.

In the subgroup of more severe patients, SpO2 levels also increased by day 14 (p < 0.001), but more significantly in the Immunovac VP4 (Fig. 9).

In the main group SpO2 levels were slightly lower compared to those in the control group (94 [94; 94)% vs. 95 [94; 95]%, respectively, p = 0.08), but on day 14 of treatment they were higher than in the control group (98 (97; 99)% vs. 97 (97; 97.8)%, p = 0.01).

Discussion

The search for new ways to influence the pathogenesis of COVID-19 in order to prevent unfavorable outcomes and potentially improve mucosal immunity encouraged us to carry out a more thorough assessment of the effects of Immunovac VP4, a bacterial-lysate agent, in COVID-19 patients in relation to their clinical status. Analysis of the clinical and laboratory data showed that patients hospitalized with a more severe disease had significantly lower sIgA levels in all NALT areas. The diagnosis of moderate-to-severe COVID-19 was confirmed by positive results with SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR), CT findings, elevated CPR levels and reduced blood oxygen saturation. The regression analysis revealed a significant inverse correlation between sIgA levels, and the percentage of lung involvement and C-reactive levels.

The correlation between sIgA levels and the severity of COVID-19 has not been fully investigated. Some authors have observed higher sIgA levels in severe COVID-19 patients31, while others report that a lower SARS-CoV-2 viral load, which results in less severe COVID-19, is correlated with higher sIgA levels and an earlier appearance of sIgA in the mucosa32. Some studies have shown that the total titer of secretory immunoglobulin A contains antibodies specific to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. And the more severe the patient’s infection, the higher the local immune defense indicators21,33. However, whether mucosal immunity prevents the shedding of the infectious virus in SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals is unknown. Miyamoto et al. examined the relationship between viral RNA shedding dynamics, duration of infectious virus shedding, and mucosal antibody responses during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Anti-spike secretory IgA antibodies (S-IgA) reduced viral RNA load and infectivity more than anti-spike IgG/IgA antibodies in infected nasopharyngeal samples. Compared with the IgG/IgA response, the anti-spike S-IgA post-infection responses affected the viral RNA shedding dynamics and predicted the duration of infectious virus shedding regardless of the immune history34. Unfortunately, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the impact of baseline total sIgA levels on the course of COVID-19 due to the lack of such studies. Although there is a lot of information about the non-specific role of sIgA in protecting the respiratory tract35,36, this issue requires additional scientific discoveries in the context of studying the Novel coronavirus infection.

Considering the multifaceted antiviral activity and anti-inflammatory properties of sIgA, some authors suggest that sIgA prevent lower respiratory tract damage in COVID-19 patients; and taking into account the aforementioned information, this suggestion seems to be well grounded28. These suggestions support the assumption that more severe COVID-19 is associated with the initially reduced production of sIgA. It has been found that sIgA in the saliva of severe COVID-19 patients is also reactive to non-novel coronavirus, and this heterologous immune response consists of a non-protective cross-reaction37. Similarly, another study showed that cross reactive SARS-CoV-2 SIgA also existed in the saliva of people non-infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, indicating that SIgA may be helpful in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection38.

In our study we examined the levels of total sIgA. The analysis of the control group data also showed that more severe patients had lower baseline pharyngeal sIgA levels, which significantly increased by day 14 and subsequently decreased by day 30 of hospital stay. Less severe patients had higher baseline sIgA levels, which only slightly increased by day 14 of hospital stay and decreased below the baseline values by study day 30. Thus, initially higher sIgA levels are a prognostic sign for a less severe illness.

A review of the literature suggests that the highest pharyngeal sIgA levels are observed 2–3 weeks after the onset of the disease, which then decrease substantially and disappear completely in 120 days39. In our study, the comparison of pharyngeal sIgA levels in the control and main groups revealed some tendencies in the subgroup of patients with less severe COVID-19: relatively higher baseline sIgA levels than in more severe patients, their slight increase on study day 14 and inverse changes on day 30 of hospital stay (a significant reduction in the control group and a significant increase in the main group, which was definitely related to the use of Immunovac VP4).

Salivary sIgA levels are harder to interpret. They show wide fluctuations because the production of sIgA is influenced not only by β-adrenergic stimulation40, intestinal flora41 and neural pathways42 but also by a number of psychological factors. For instance, it was shown that exposure to videos related to COVID-19 significantly increased the production of salivary SARS-CoV-2-specific sIgA43. Although according to the common classification salivary glands are considered part of NATL, it should be acknowledged that their morphology and physiology, including participation in the regulation of sIgA secretion, make them significantly different from other compartments of the nasopharynx. Of note, considerably higher sIgA levels were seen in healthy people but not in COVID-19 patients44.

The absence of any significant changes in nasal sIgA levels was expected. The upper respiratory tract and oral cavity are quite different both in terms of cellular composition and, consequently, immune responses. Local immunodeficiency in the nasal cavity may indicate viral damage to epitheliocytes, which might lead to frequent respiratory infections, and probably requires additional immunocorrective approaches aimed at enhancing mucosal immunity, for example, nasal form of medication containing bacterial ligands or recombinant interferons45.

The most important finding was a clear increase in pharyngeal sIgA levels, which was associated with the use of Immunovac VP4. This change was most noticeable by day 30 of treatment because by this time the elevation of sIgA levels triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection is much less significant. Similar results were previously reported with the use of Immunovac VP4 as immunotherapy in children with frequent and long-lasting illnesses46. Such effects of this agent are explained by the ability of Immunovac VP4 to stimulate maturation of dendritic cells and expression of co-stimulating and antigen-presenting molecules, including CD40 и interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1047, which are mediators in the main cytokine pathway regulating sIgA production48.

In hospitalized COVID-19 patients continuous non-invasive monitoring of blood oxygen saturation was necessary, and SpO2 levels were an important indicator of the degree of respiratory failure and the patient’s response to respiratory support49,50. In our study, patients with only mild respiratory failure did not require additional respiratory support except for low-flow oxygen therapy (up to 3 L/min). It should be noted that pulse oximetry was performed after at least a 15-min break after inhalation of humidified oxygen. One of the study objectives was to investigate the effects of immune therapy on SpO2 levels in COVID-19 patients. Analysis of data collected from patients receiving the standard treatment in accordance with the clinical guidelines developed by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation and those who were additionally given Immunovac VP4, as part of a combination treatment, starting from day 1 of hospital stay showed similar changes in SpO2 levels, which increased in both groups. However, in the Immunovac VP4 group this increase was more significant than in the control group (p = 0.01). We associate these results with the possible positive effect of immunotropic therapy on local immunity, in particular associated with the production of secretory immunoglobulin A in the respiratory sections of the lungs, as well as the activation of cellular mechanisms of immune defense, which helps resolve inflammatory changes in lung tissue, reduce the degree of alveolar exudation, which is reliably associated with an improvement in oxygen status 51. In vitro studies from our laboratory recently demonstrated that bacterial-lysates inhibits SARS-CoV-2 epithelial cell infection by downregulating SARS-CoV-2 receptor expression, raising the possibility that this bacterial extract might eventually complement the current COVID-19 therapeutic toolkit52.

A disadvantage of our study was that we assessed only a few clinical features. We also did not evaluate the level of specific immunoglobulin A against the Sars-CoV-2 virus. In our previous papers we reported a more significant reduction in the intensity of inflammation on day 5 of illness in the Immunovac VP4 group compared to the control group, which was reflected by a significantly greater reduction in CRP levels, the duration of fever, and the length of hospital stay10,11.

It should also be noted that treatment with this bacterial lysate-based therapeutic agent resulted in restoration of sIgA levels, regardless of the magnitude of their initial reduction. This suggests that this medication might influence the mechanisms of post-COVID-19 syndrome. In COVID-19 patients, the study drug Immunovac VP4, a microbial-based immunomodulating agent induces the production of sIgA in the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract. This plays an essential role in achieving control over the infection in a timely manner and proving protection from the disease-causing pathogen.

Zhu et al. reveal new roles of bacterial lysates: OM-85 were discovered in prevention and treatment of lung cancer, pulmonary tuberculosis, SARS-CoV-2 infection, allergic rhinitis, pulmonary fibrosis, atopic dermatitis, and nephrotic syndrome. Pharmacoeconomic values of OM-85 were demonstrated in prophylaxis and treatment of RTIs, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, chronic bronchitis, rhinosinusitis and allergic rhinitis. Two consecutive courses of OM-85 (6 or 12 months apart) could prevent recurrent RTIs in children. Maternal OM-85 treatment could offer benefits for offspring. Product-specific response was observed. The efficacy of OM-85 may be associated with patient’s characteristics (eg, severity of the disease, age, immune response pattern, malignancy risk stratification)53. A wide range of anti-viral properties of sIgA, which are active at the site of pathogen invasion, bacterial lysates can be considered a promising drug for comprehensive prevention and treatment of viral droplet infections.

Our study has several limitations. First of all it is lack of a study of the level of specific antiviral antibodies of the respiratory tract mucosaю We also studied a group with moderate COVID-19, and therefore it is not possible to assume the dynamics of clinical and laboratory parameters in the group with severe or mild disease. We also did not conduct a quantitative assessment of the viral load using PCR research, which could be a more accurate method for assessing the effectiveness of therapy, but relied on clinical and instrumental parameters that indirectly reflect the severity of the infection. Nevertheless, drugs based on bacterial ligands (in particular, Immunovac VP-4) can play an important role in immunomodulation of the course of COVID-19 and have a positive effect on clinical and laboratory parameters and recovery of patients. However, this area requires further research to study this problem. Here we discuss how our results and those from other groups are fostering progress in this field of research.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lavelle, E. C. & Ward, R. W. Mucosal vaccines—fortifying the frontiers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22(4), 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-021-00583-2 (2022).

Jurkiewicz, D. & Zielnik-Jurkiewicz, B. Bacterial lysates in the prevention of respiratory tract infections. Otolaryngol. Pol. 72(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0012.7216 (2018).

dos de Santos, J. M. B. et al. In nasal mucosal secretions, distinct IFN and IgA responses are found in severe and mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 12, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.595343 (2021).

Kaufman, L. & Rousseeuw, P. J. Finding Groups in Data An Introduction to Cluster Analysis 342 (Wiley, 1990). https://doi.org/10.2307/2532178.

Protasov, A. D., Zhestkov, A. V., Lavrenteva, N. E., Kostinov, M. P. & Ryzhkov, A. A. Effect of complex vaccination against pneumococcal, Haemophilus type b infections and influenza in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Zh Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 4, 80–84 (2011).

Ryzhov, A. A., Kostinov, M. P. & Magarshak, O. O. The use of vaccines against pneumococcal and hemophilic type b infections in patients with chronic pathology. Epidemiol. i Vaktsionoprofilaktika. 19(6), 24–27 (2004).

Rukovodstvo po klinicheskoy immunologii v respiratornoy meditsine. [Clinical immunology guide to respiratory medicine] 2nd edn, (eds Kostinov, M. P., Chuchalin A. G.) pp, 304 (Gruppa MDV Publication, Moscow, 2018).

Avdeev, S. N. et al. Clinical efficacy of mechanical bacterial lysate in the prevention of infectious exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Terapevticheskiy Arkhiv. 92(4), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.26442/00403660.2020.04.000590 (2020).

Ilyinykh, E. A., Stafeeva, O. N. & Utkina, N. P. Morphological characteristics of lymphoid organs and epithelioassociated lymphoid tissue in various methods of administration of the bacterial vaccine VP-4. Successes Mod. Natural Sci. 7, 48–49 (2010).

Kostinov, M. et al. Changes in nasal, pharyngeal and salivary secretory IgA levels in patients with COVID-19 and the possibility of correction of their secretion using combined intranasal and oral administration of a pharmaceutical containing antigens of opportunistic microorganisms. Drugs Contexts 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.2022-10-4 (2023).

Kostinov, M. et al. Secretory IgA and course of COVID-19 in patients receiving a bacteria-based immunostimulant agent in addition to background therapy. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 11101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61341-7 (2024).

Russell, M., Kilian, M., Mantis, N. & Orthésy, B. Biological Activities of Mucosal Immunoglobulins 429–454 (Academic Press, 2015).

Roda, A. et al. Dual lateral flow optical/chemiluminescence immunosensors for the rapid detection of salivary and serum IgA in patients with COVID-19 disease. Biosens. Bioelectron. 172, 112765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2020.112765 (2021).

Pearson, C. F., Jeffery, R., Thornton EE, Consortium O-CC-L. Mucosal immune responses in COVID19—A living review. Oxf. Open Immunol. 2(1), iqab002. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfimm/iqab002 (2021).

Esmat, K. et al. Immunoglobulin A response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and immunity. Heliyon 10(1), e24031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24031 (2024).

Sinha, D. et al. Unmasking the potential of secretory IgA and its pivotal role in protection from respiratory viruses. Antiviral Res. 223, 105823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2024.105823 (2024).

Barzegar-Amini, M. et al. Comparison of serum total IgA levels in severe and mild COVID-19 patients and control group. J. Clin. Immunol. 42(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-021-01149-6 (2022).

Santos, J. M. B. et al. In nasal mucosal secretions, distinct IFN and IgA responses are found in severe and mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 12, 595343. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.595343 (2021).

Chuchalin, A. G. Respiratornaya meditsina. Rukovodstvo. [Respiratory medicine. Guidelines] 2nd edn, Vol. 2, pp. 544 (Moscow, Litterra Publication, 2017).

Avedisova, A. S., Ametov, A. S. & Anokhina, I. P. Federal Guidelines for the Use of Medicines (Formulary System) Vol. 15, 1020 (Echo, 2014).

Kostinov, M. P., Zorin, N. A., Kazharova, S. V. & Zorina, V. N. Comparative effect of immunomodulators on the contents of hydrolase inhibitors and lactoferrin in community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Med. Immunol. (Russia) 22(4), 791–798. https://doi.org/10.15789/1563-0625-CEO-1548 (2020).

Kostinov, M. P. et al. The effect of immunomodulators on various markers of the acute inflammation phase in patients with mild community-acquired pneumonia. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 99(4), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.21292/2075-1230-2021-99-4-36-43 (2021).

Tajima, Y., Suda, Y. & Yano, K. A case report of SARS-CoV-2 confirmed in saliva specimens up to 37 days after onset: Proposal of saliva specimens for COVID-19 diagnosis and virus monitoring. J. Infect. Chemother. 26(10), 1086–1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2020.06.011 (2020).

To, K. K. et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: An observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20(5), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1 (2020).

Chen, J. H. et al. Evaluating the use of posterior oropharyngeal saliva in a point-of-care assay for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9(1), 1356–1359. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751 (2020).

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S 4th edn. (Springer, 2002).

Hartig, F., Hartig M. F. Package ‘DHARMa’. R package. (2017).

Koller, M. Robustlmm: An R package for robust estimation of linear mixed-effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 75(6), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v075.i06 (2016).

Nakagawa, S., Johnson, P. C. D. & Schielzeth, H. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J. R. Soc. Interface 14(134), 20170213. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2017.0213 (2017).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82(13), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13 (2017).

Dos Santos, J. M. B. et al. In nasal mucosal secretions, distinct IFN and IgA responses are found in severe and mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 25(12), 595343. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.595343 (2021).

Fröberg, J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mucosal antibody development and persistence and their relation to viral load and COVID-19 symptoms. Nat Commun. 12(1), 5621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25949-x (2021).

Escalera, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces robust mucosal antibody responses in the upper respiratory tract. iScience 27(3), 109210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109210 (2024).

Miyamoto, S. Infectious virus shedding duration reflects secretory IgA antibody response latency after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 120(52), e2314808120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2314808120 (2023).

Park, S. C. et al. Induction of protective immune responses at respiratory mucosal sites. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 20(1), 2368288. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2024.2368288 (2024).

Bertrand, Y. et al. IgA-producing B cells in lung homeostasis and disease. Front. Immunol. 14, 1117749. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1117749 (2023).

Smit, W. L. et al. Heterologous immune responses of serum IgG and secretory IgA against the spike protein of endemic coronaviruses during severe COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 13, 839367 (2022).

Tsukinoki, K. et al. Detection of cross-reactive immunoglobulin A against the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 spike 1 subunit in saliva. PLoS ONE 16(11), e0249979 (2021).

Russell, M. W., Moldoveanu, Z., Ogra, P. L. & Mestecky, J. Mucosal immunity in COVID-19: A neglected but critical aspect of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 11, 611337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.611337 (2020).

Ren, C. et al. Respiratory mucosal immunity: Kinetics of secretory immunoglobulin A in sputum and throat swabs from COVID-19 patients and vaccine recipients. Front. Microbiol. 13, 782421. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.782421 (2022).

Okabayashi, K., Wakao, Y. & Narita, T. Release of secretory immunoglobulin A by submandibular gland via β adrenergic receptor stimulation. Arch. Oral Biol. 29, 105209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2021.105209 (2021).

Durand, D. et al. Secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) in saliva versus virulence proteins of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) in ill and colonized children. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 38(6), 279–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eimc.2019.08.006 (2020).

Carpenter, G. H., Proctor, G. B. & Garrett, J. R. Preganglionic parasympathectomy decreases salivary SIgA secretion rates from the rat submandibular gland. J. Neuroimmunol. 160(1–2), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.10.020 (2005).

Keller, J. K. et al. SARS-CoV-2 specific sIgA in saliva increases after disease-related video stimulation. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 22631. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47798-y (2023).

Hind, H. et al. Secretory IgA levels among COVID-19 patients. JODR J. https://doi.org/10.58827/703425eyjjim (2023).

Foshina, E. P., Serova, T. A., Bisheva, I. B. & Slatinova, O. V. The effectiveness of immunovac VP4 for immunological parameters in frequently and long-term ILL children. Zh. Mikrobiol. 96(1), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.36233/0372-9311-2019-1-104-110 (2019).

Egorova, N. B., Kurbatova, E. A., Akhmatova, N. K. & Gruber, I. M. Polycomponent vaccine immunovac-VP-4 and immunotherapeutic concept of its use for the prevention and treatment of diseases caused by opportunistic microorganisms. Zh. Mikrobiol. 96(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.36233/0372-9311-2019-1-43-49 (2019).

Macpherson, A. J., McCoy, K. D., Johansen, F. E. & Brandtzaeg, P. The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal Immunol. 1(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2007.6 (2008).

Sherlaw-Johnson, C. et al. The impact of remote home monitoring of people with COVID-19 using pulse oximetry: A national population and observational study. EClinicalMedicine 45, 101318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101318 (2022).

Sobel, J. A. et al. Descriptive characteristics of continuous oximetry measurement in moderate to severe covid-19 patients. Sci. Rep 13(1), 442. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27342-0 (2023).

Zamani Rarani, F. et al. Comprehensive overview of COVID-19-related respiratory failure: Focus on cellular interactions. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 27(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-022-00363-3 (2022).

Pivniouk, V. & Vercelli, D. The OM-85 bacterial lysate: A new tool against SARS-CoV-2?. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 18, 906. https://doi.org/10.4081/mrm.2023.906 (2023).

Zhu, L. L. et al. Oral bacterial lysate OM-85: Advances in pharmacology and therapeutics. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 18, 4387–4399. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S484897 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. – head of the study, design, description of results, A.C. – study coordinator, scientific advisor, O.S. – study coordinator, scientific advisor, V.G. – description of results, K.M. – collection of literature materials, preparation of bibliography, description of results, N.K. – material processing, responsible for correspondence with reviewers, V.O. – collecting of the material, observation of clinical status of patients, evaluation of long-term results, V.T. – collecting of the material, observation of clinical status of patients, evaluation of long-term results, E.K. – conducting immunological studies, I.B. – research coordinator, legal and ethical support of the research, A.V. – statistical analysis, L.S. – research coordinator, legal and ethical support of the research, I.M. – collecting and processing the material, I.K. – responsible for preparation of tables and figures, A.L. – material processing, A.K. – processing of the material, translation, V.P. – conducting immunological studies, A.P. – preparation of bibliography, transportation of biomaterial.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kostinov, M., Chuchalin, A., Svitich, O. et al. Bacterial lysates in modifying sIgA levels in the upper respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 15, 8325 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92794-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92794-z