Abstract

A novel approach for synthesizing Titanium Oxide nanoparticles (NPs) using the rotating electrode in arc discharge method was developed by focusing on enhanced photocatalytic activity. Utilizing a rotating electrode as a third electrode in the arc discharge process enables us to synthesize defective titanium oxide, which facilitates the effective decoration with Ag NPs. Silver-decorated Titanium Oxide (Ag/Titanium Oxide) NPs were synthesized via a photoreduction process, improving visible light response through surface plasmon resonance which introduces new energy levels near the conduction band. The Ag/Titanium Oxide NPs exhibited high degradation of Rhodamine B dye, achieving 98% removal under visible light, attributed to the efficient charge separation. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed uniform morphology and size distribution and X-ray diffraction (XRD) also identified the crystalline phases (anatase and rutile). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) confirmed the chemical states and successful silver deposition. UV–visible spectroscopy along with photoluminescence (PL) analysis determined the optical properties. BET surface area measurements indicated enhanced surface area, supporting improved photocatalytic efficiency. These results highlight the potential of Ag/Titanium Oxide composite in designing advanced photocatalysts for environmental applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water pollution is a serious global concern, containing hazardous materials like dyes, pesticides, oils, medicines, and other organic molecules. Nevertheless, the dye industries produce about 70% of pollutants that should be treated through eco-friendly and efficient technologies. Among organic-based dyes, cationic dyes threaten the health and life of living things. Rhodamine B dye is a high molecular weight and refractory dye that causes oxidative stresses on cells and tissue liver, resulting in cancers, and when exposed in large amounts over a short period, it results in acute poisoning1,2,3. Novel technologies have been proposed for the remediation of dye-contaminated wastewater, such as membranes, coagulation, electrolysis, absorbent materials, photocatalysis, and so on. Among the different techniques, photocatalysis is a promising method for eliminating pollutants from wastewater using the renewable and sustainable energy of the sun4,5,6. A photocatalyst in the presence of light produces active species such as hydroxyl radicals, hole, and superoxide radicals that attack organic-based molecules7. A photocatalyst logically should be inexpensive, green, accessible, narrow bandgap (Eg), high specific BET surface area (SBET), low charge recombination rate, and high light absorption capability. Nevertheless, more photocatalysts have some drawbacks that need to improve their properties through different strategies such as elemental doping, coupling to other photocatalysts, changing morphology, etc. Hence, novel synthesis methods can play a determining role in obtaining the desirable photocatalysts8,9,10.

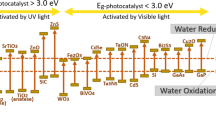

Titanium Oxide is one of the most popular and effective photocatalysts with a wide bandgap (Eg ~ 3 eV for rutile, and ~ 3.2 eV for anatase), making pure Titanium Oxide active under UV irradiation11,12. The wide application of Titanium Oxide is attributed to advantages: such as low production costs, robust physio-chemical stabilities, corrosion resistance, high UV-light-driven reactivity, and strong oxidizing agent with a large SBET13,14. However, Titanium Oxide has limitations in terms of its photocatalytic efficiency due to its wide bandgap (Eg = 3.20 eV). Some approaches including crystalline modification, surface improvement, and coupling to other photocatalysts are reported to fortify and even extend light-capturing capability in the visible range15,16,17.

A prevalent strategy for the wide bandgap problem is non-zero-valent metals such as Ag0 that could extend the absorption band to the visible light region. Non-zero-valent metals like Ag0 act as Schottky junction catalysts that excite electrons toward molecules as well as its localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), allowing light-to-chemical energy transformation in a photocatalytic reaction18,19. Moreover, Ag0 has better stability against oxidation in comparison to other active metals20,21,22,23. Therefore, photocatalysis using Ag/Titanium Oxide nanocomposite can be considered as a photocatalyst for various chemical reactions under visible light. Titanium Oxide and Ag can elevate the charge separation/transport performances and the light absorption activity, helping to enhance light-driven wastewater remediation than pure Titanium Oxide. In these photocatalytic mechanisms, the UV-photo-excited electrons in the Titanium Oxide transform to Ag for progressing photocatalysis24. However, the use of silver in photocatalysts presents both advantages and environmental concerns, particularly regarding the potential leaching of silver ions into water bodies. While silver is known for its antimicrobial properties and can enhance the photocatalytic efficiency of materials like titanium dioxide, the release of silver ions into aquatic environments raises significant ecological issues. Silver ions can be toxic to a variety of aquatic organisms, disrupting ecosystems and potentially bioaccumulating in the food chain. This leaching can occur due to environmental factors such as pH changes, temperature fluctuations, and the presence of organic matter, which may facilitate the dissolution of silver from the photocatalytic material. Therefore, while silver-enhanced photocatalysts can effectively degrade pollutants and improve water quality in controlled applications, careful consideration must be given to their long-term environmental impact, necessitating the development of strategies to mitigate silver leaching and ensure the sustainability of such technologies.

The synthesis of Schottky junction catalysts using visible-sensitized titanium dioxide semiconductors poses significant challenges, particularly in producing defective titanium dioxide that can effectively support the growth of metal nanoparticles, such as silver (Ag⁰), which can enhance photocatalytic activity25. Existing methods often do not optimize the defect density in titanium dioxide, which is crucial for enhancing catalyst performance26,27,28,29. Our novel synthesis method utilizes the arc discharge technique in a deionized (DI) water medium to produce titanium dioxide nanoparticles with an increased defect density. This enhancement facilitates the effective growth of silver nanoparticles, resulting in a robust Schottky junction. The hybrid material that emerges leverages the plasmonic resonance of the metallic NPs on titanium dioxide, significantly improving photocatalytic performance and addressing the limitations of previous synthesis approaches. Furthermore, the scalability of the arc discharge synthesis method represents a notable advancement in producing defect-rich titanium dioxide nanoparticles, which are essential for high-performance catalysts in various real-world applications30,31,32,33. As the demand for such catalysts continues to grow, the ability to efficiently produce these nanoparticles on a large scale becomes increasingly critical. This method not only meets industrial requirements by enabling substantial production quantities but also ensures consistent quality and performance across different batches. By integrating this scalable synthesis technique into existing production processes, industries can significantly enhance their capacity to develop innovative catalysts. This advancement has the potential to contribute to more sustainable and effective solutions in key areas such as environmental remediation and energy conversion, ultimately supporting the transition toward a more sustainable future. In addition, the cost analysis of photocatalyst production via the arc discharge method suggests that while the initial setup and energy costs are high, the potential for high yield and purity can lead to cost-effectiveness over time. To ensure economic viability for large-scale environmental applications, it is crucial to optimize energy efficiency and reduce operational costs while meeting market demand.

In this study, we employed a novel method by using the rotating electrode as the third electrode in the arc discharge process. Resulting Titanium Oxide NPs exhibit prose and defective Titanium Oxide promising to decorate with Ag NPs. We investigated the effects of the incorporation of Ag NPs with different concentrations on photocatalytic performance. The resulting Ag/Titanium Oxide NPs display distinct photocatalytic behaviors, attributed to special physicochemical properties, which are explored by various analytical methods.

Experimental

Materials

To fabricate the photocatalysts, the following materials were used: three Titanium metal rods (with 20 cm length and 5 mm diameter (99.9%)) as arc discharge electrodes. Silver Nitrate anhydrous (AgNO3, 99%) prepared from Merck company. Rhodamine B dye (RhB, ≥ 95%) from Mojalali Co. (Iran). DI water obtained from Ultra2pure device. All experiments were used without further purification steps.

Photocatalysts synthesis

Synthesis of titanium oxide NPs

Three Ti rods were used in the arc discharge process. One rod was connected to the cathode and the second rod was connected to the anode at an angle of 45° with a 5 mm distance. The ends of the electrodes were immersed in 700 mL of DI water; then, the third rod was connected to a rotary motor with 800 rpm, which was placed in the interval between the cathode and anode rods. Afterward, a DC current with a value of 30 A and a voltage of 15 V was applied. The third rotating electrode connected the anodic and cathodic electrodes, creating an arc discharge between these electrodes in DI water. This arc discharge process was repeated 4 times. In this process, Titanium Oxide NPs were produced by melting the surfaces of the rods due to arc current and immediately oxidized. The color of the aquatic medium forms a nearly dark blue color due to the produced Titanium Oxide NPs31,34. The experimental conditions of 30 A, and 15 V were chosen to optimize the synthesis of Titanium Oxide nanoparticles with enhanced defects. The 800 rpm speed ensures effective mixing and control over particle size, while the 30 A current provides sufficient energy for vaporizing Titanium and generating defects essential for silver nanoparticle growth. A voltage of 15 V between fixed electrodes maintains a stable arc discharge, ensuring consistent nanoparticle production and influencing their morphology.

Synthesis of Ag/Titanium oxide

100 mL of AgNO3 solution with the desired amount of silver (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 g) was gradually added to the prepared Titanium Oxide suspension under continuous stirring. Immediately, the Titanium Oxide NPs began to precipitate due to strong electrostatic interactions between the positively charged Ag+ and the Titanium Oxide surfaces. This led to the nucleation and growth of Ag+ on the Titanium Oxide surface. Then, the mixture was left to stand under ambient laboratory conditions without light exposure for 1 day. Following this step, the obtained mixture was split into two samples. The first sample was irradiated with a UV-A lamp (Philips, 6 W) for 2 h, while the second sample was exposed for 10 h. We name these irradiated samples according to UV irradiated time as the Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h) and Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h), respectively35. This irradiation process helped the Ag+ ions reduction on the Titanium Oxide NPs defects as shown in Fig. 1. Finally, the prepared samples were collected, and dried at 100 °C.

Characterization

The X-ray diffraction experiments were carried out by Bruker D8 (USA) using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). The crystallite sizes were calculated using the Scherrer equation:

where D, k, λ, β, and θ are the average crystallite size, the Scherrer’s constant (0.89–0.9), the X-ray wavelength, the full width at half maximum (FWHM), and the Bragg angle, respectively. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM; MIRA3, Tescan, Czech) was used to study the surface morphology of photocatalysts; in addition, the surface composition and distribution of the elements detected by Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the composite were obtained to investigate the particles size. The instrument used was a JEOL 100CXII operating at 200 kV. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) studies were performed using a NEXSA (Thermo Scientific) spectrometer with an Al X-ray source. The UV-vis Spectrophotometer (UV-vis 700, OPTC Co., Iran) was used to measure the removal efficiency of RhB (R (%)). The photoluminescence (PL) spectra of samples were obtained by a Perkin-Elmer spectrophotometer (LS 45, USA). Brunauer-Emmet Teller (BET) and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) were utilized to determine the SBET, pore size, and pore volume via the N2 (g) adsorption-desorption method. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed using the Radostat 10 multi-channel system from Kian Shar Danesh.

Photocatalytic tests measurement

The photocatalytic activity was examined by the degradation of RhB under visible light. Experimental details are as follows: the photocatalyst (0.03 g) was dispersed into 50 mL of RhB solution (20 ppm) in a glass beaker. The prepared suspension was stirred for 30 min in dark conditions; subsequently, it was irradiated under a Xenon lamp (55 W). Every 1 h, 5 mL of suspension was taken from the reaction beaker and centrifuged to remove the particles. Afterward, the residual dye concentration in the upper transparent solution was determined by measuring the dye solution’s absorbance at the wavelength of 553 nm by a UV-vis spectrophotometer. Finally, the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of RhB was calculated from the Eq. 1:

where A0 represents the initial concentration of RhB, At is the concentration of RhB at time intervals36,37.

Results and discussion

Morphology and structure

The XRD was utilized to determine the crystalline phase of the prepared samples. Figure 2 shows the diffraction patterns of the Titanium Oxide and Ag/Titanium Oxide NPs. The results in Fig. 1 indicate the presence of anatase and rutile phases in the prepared Titanium Oxide. The characteristic diffraction peaks at 2ϴ = 25.3°, 37.3°, 53.8°, 54.9°, 62.4°, and 75.2° are assigned to anatase phase, which are indexed to the (101), (004), (105), (211), (204), and (215) crystal planes, respectively. The diffraction peaks located at angles 27.5°, 36.3°, 40°, 41.3°, and 43.2° are assigned to (110), (101), (200), (111), and (210) crystal planes of rutile phase, respectively. The results correspond to the JCPDS card No. 00-021-1272 for the anatase phase and the JCPDS card No. 00-021-1276 for the rutile phase4,6,38. From Eq. 2 the average crystalline size of Titanium Oxide NPs determined from the (101) band for anatase is calculated as 28.4 nm, and the (011) index of rutile gives 21.2 nm. Similarly, the Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h) shows diffraction peaks for the anatase and rutile phases, while the diffraction peak (111) of the Ag NPs is added to the pattern which gives the average crystalline size of 22 nm. In addition, other diffraction peaks are seen for the Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) at 38.2°, 44.7°, 64.4°, and 77.4°, which are respectively attributed to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) indexes of the Ag NPs according to JCPDS card No. 04-0783 39,40. According to Eq. 2, the average crystalline size of the Ag in Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) is calculated as 21 nm.

The size and morphological features of the prepared samples were investigated using FE-SEM. As shown in Fig. 3a, and b Titanium Oxide NPs have spherical coral-like shapes with a size of less than 20 nm. Results show a porous surface of Titanium Oxide NPs in clusters without any secondary structure. The size distribution histogram for Fig. 3b shows the particles in the 15–20 nm range. Figure 3c and d for the Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h) show a large amount of Ag on the Titanium Oxide caused more aggregation than the sample of Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) as depicted in Fig. 3e and f. Results show that increasing the photoreduction time Ag+ reduction to Ag0 makes the surface of Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) softer and more spherical than the previous sample. The EDS pattern of the prepared samples in Fig. 4a and b shows the weight and atomic percentages of Ag, Ti, and O39,41, showing successful preparation.

Figure 5 presents the TEM images of the Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) composite and size distribution histogram. The TEM images also confirm the formation of nanoparticles.

XPS analysis was conducted to investigate the electronic state and chemical composition of the prepared samples as illustrated in Fig. 6. The surface chemical composition and electronic states were examined with calibrating peak positions by use of the C 1s core level at 285 eV as the reference binding energy. Figure 6a shows the survey spectrum of Titanium Oxide and Ag/Titanium Oxide. As shown the characteristic peaks for Ti 2p, O 1s, and C 1s are observed for both samples. Specifically, peaks at the binding energy of 458.3 eV, 367.2 eV, and 529.5 eV are attributed to Ti 2p, Ag 3d, and O 1s, respectively. However, an additional peak in the Ag/Titanium Oxide spectrum confirms the presence of Ag and the successful incorporation of Ag into the Titanium Oxide substance42,43,44.

Figure 6b displays the high-resolution XPS spectrum of Ti 2p for Titanium Oxide. The two intense peaks at 464.0 eV and 458.3 eV are observed, corresponding to Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2, respectively. The peak separation of 5.7 eV confirms the presence of Ti4+. Additionally, a low-intensity peak at 457.5 eV indicates Ti3+, suggesting some Ti4+ reduction to Ti3+45. For Ag/Titanium Oxide (Fig. 6e), a shift with a value of 5 eV was observed in the spectra due to the incorporation of Ag NPs. The peaks for Titanium Oxide shifted to the lower binding energies (462.3 eV and 456.3 eV for Ti4+) and new peaks emerged at 460.4 eV and 455.0 eV, attributed to Ti3+. This shift indicates the presence of oxygen vacancies and strong interactions between Ti and Ag, which likely results from the formation of Ti–O–Ag bonds within the Ag/Titanium Oxide. The shift also can be due to electronic charge transfer between Titanium Oxide and metallic Ag, with an overlap of their 3d orbitals42,46. Figure 5c and f exhibit the high-resolution O 1s spectra. For Titanium Oxide, peaks centered at 529.7 eV, 530.0 eV, and 531.8 eV correspond to lattice oxygen, Ti-O, and Ti-OH groups, respectively. In contrast, the Ag/Titanium Oxide sample shows two primary peaks at 527.7 eV and 529.7 eV, indicating alterations in the oxygen environment. The Ag 3d spectra in Fig. 6d exhibit peaks at 365.8 eV and 372.0 eV, with a spacing of 6.2 eV, consistent with Ag 3d5/2 and Ag 3d3/2, indicating Ag+. Additionally, distinct peaks at 367.3 eV and 373.3 eV, separated by 6.0 eV, confirm the presence of metallic Ag (Ag0) within the Ag/Titanium Oxide composite47,48,49.

The UV–vis spectroscopy was used to study the optical properties of the prepared samples. As shown in Fig. 7a the as-prepared samples exhibit a broad absorption spectrum in the wavelength region below 410 nm. This can be attributed to the band-band electron transition of the Titanium Oxide NPs, consistent with its band gap energy of 3.2 eV. The strong peak at around 247 nm is attributed to the intrinsic structure of Titanium Oxide, showing excellent UV-light absorption. At the UV-vis spectrum of Ag/Titanium Oxide, the broad absorption in the range of 340–600 nm is ascribed to the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect of Ag NPs. The Ag NPs deposition on Titanium Oxide causes a redshift in the absorption edge that can improve photocatalytic performance in the visible region50. The Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) has an absorption edge at 440 nm matching the band-gap energy of 2.8 eV which is lower than Titanium Oxide (3.2 eV). The low band-gap energy means that less activation energy is required for electron-hole separation51.

The PL spectra of semiconductors are shown in Fig. 7b. The PL spectrum demonstrates the charge recombination behavior, and a weak PL peak is attributed to the good separation of hole and photoelectron. The Titanium Oxide NPs exhibit a highly intense and extensive PL band at 365 nm, showing faster electron-hole recombination than other samples. As shown, the PL emissions of the Ag/Titanium Oxide samples were almost extremely suppressed due to the presence of Ag NPs on the surfaces of the Titanium Oxide that can trap electrons to inhibit the electron-hole recombination. According to Fig. 7b, the band intensity of Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) is lower than Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h). Consequently, the pronounced charge separation is observed for the Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) composite51,52,53.

To evaluate the resistance of the nanocomposite to electron transfer, EIS measurements were conducted (Fig. 7c). Comparative measurements were also performed on the prepared Titanium Oxide nanoparticles. The linear sections of the curves indicate Warburg impedance, which is associated with the diffusion of sodium ions into the bulk of the electrode. The charge-transfer resistance (Rct) for the Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h) was measured at 15.83 Ω, significantly lower than the value for Titanium Oxide (49.13 Ω). This reduction in Rct indicates improved electron transfer and higher efficiency of the nanocomposite in photocatalytic applications. Furthermore, the Solid Electrolyte Interphase resistance (Rs) for Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) was found to be 4.45 Ω, which is lower than that of Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h) (15.83 Ω). This decrease in Rs also suggests enhanced electronic and ionic conductivity in the photocatalyst. Overall, the results indicate that the synthesis time has a significant impact on the electrochemical properties of the nanocomposite and can contribute to improved performance in various applications.

The BET and BJH are utilized to calculate the SBET and the pore-size distribution of samples, respectively. Figures 8 and 9 exhibit the characteristic plot of N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm and the pore size distribution curve of the as-prepared samples. As shown in Fig. 8, the hysteresis loops are the isotherm type-IV with the Brunauer-Deming-Deming-Teller. The hysteresis loop of Titanium Oxide NPs at relative higher-pressure range of 0.5–0.9 shows the absorption nature of the NPs, which is often found in agglomerated NPs. The corresponding pore-size distribution of the samples is shown in Fig. 9. As shown, the pore-size distribution graphs specified that Titanium Oxide NPs have a moderately broadened distribution50,54. According to Table 1, the BET surface area of Titanium Oxide NPs was calculated to be 40.6 m2/g, while the SBET of Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h) decreased (12 m2/g) due to the aggregation process caused by the presence of Ag. However, for the Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) sample, the BET surface area increases (203 m2/g) probably due to the uniform distribution of Ag NPs which causes the aggregation decrease. As seen, there is a large surface area and a lesser average pore diameter for Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) in comparison with Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h) as advantageous for enhancing adsorption performance49.

Photocatalytic activity

The RhB was used to measure the photocatalytic activity of the prepared samples. The absorption intensity at the wavelength of 553 nm was used as a reference and the photocatalytic tests were done within 300 min. At first, we prepared several samples with different concentrations of Ag agents in a Titanium Oxide solution and exposed them to UV radiation for 2 h. Figure 10a shows the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of RhB for Ag/Titanium Oxide composites with different amounts of Ag. According to Fig, pure Titanium Oxide NPs did not exhibit strong photocatalytic activity under visible light, giving a degradation rate of about 8%. In contrast, decorated samples with Ag (i.e. Ag/Titanium Oxide samples) improved the degradation rate, confirming the synergetic effect of Ag. The Ag/Titanium Oxide composite with the amount of silver 0.4 g exhibited the most photocatalytic activity and RhB degradation.

When the silver content exceeds 0.4 wt%, there is a noticeable decline in photocatalytic activity. This reduction can be attributed to several factors related to the physical characteristics of the silver particles formed on the Titanium Oxide surface. As the amount of silver increases, it tends to aggregate and form larger, non-uniform particles. These larger particles can significantly diminish the effective active surface area of Titanium Oxide, which is crucial for facilitating photocatalytic reactions. A smaller active surface area means fewer sites are available for the adsorption of reactants, ultimately leading to a decrease in the overall photocatalytic efficiency. Additionally, the aggregation of silver into larger particles can block active sites on the Titanium Oxide surface. This obstruction not only limits the availability of these sites for catalytic reactions but also restricts the penetration of light, which is essential for activating the photocatalytic process. When light access is hindered, the excitation of electrons in the Titanium Oxide is reduced, further impeding the photocatalytic reactions. Therefore, while silver deposition can enhance photocatalytic activity at lower concentrations, exceeding the optimal level leads to adverse effects that compromise the overall effectiveness of the Titanium Oxide photocatalyst.

Next step, Ag/Titanium Oxide (Ag: 0.4 g), as the optimum sample, was exposed to UV radiation for 10 h to investigate the effect of UV duration. The degradation results are shown in Fig. 10b. As seen, the degradation efficiency is proportional to UV duration because of the amount of produced silver. The degradation rate of the Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) sample is more than that of the Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h). The Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h) sample shows a synergistic effect in the porous channels, which leads to more oxidation and reduction processes as well as high degradation of the dye. The production rate of reactive oxygen species depends primarily on incident light, which can give the degradation rate of 98% for RhB55. The XPS analyses showed the presence of oxygen vacancies in the Ag/Titanium Oxide composite. The oxygen vacancies can act as electron traps, helping to reduce the recombination rate of electron-hole pairs. By capturing electrons, the lifetime of charge carriers prolongs and allows them to participate in redox reactions. Our results offer that photocatalytic activities of Ag/Titanium Oxide enhanced remarkably by forming a Schottky junction37.

Total organic carbon (TOC) was determined to study the mineralization of small aromatic compounds produced from the photodegradation of RhB dye. An efficiency of 86% were achieved for mineralization of RhB by Ag/Titanium Oxide composite (10 h). It shows that the degraded RhB dye is broken down into CO2 and H2O at the end of the photocatalytic process, highlighting the complete mineralization attributes of the Ag/Titanium Oxide composite.

Photo-degradation mechanism

Scavenger tests were conducted to identify the individual contributions of active species in the photocatalytic degradation of RhB. The isopropyl alcohol (IPA) was employed for quenching ·OH, benzoquinone (BQ) for ·O2−, and ammonium oxalate (AO) for h+, which are generated during light irradiation process. As shown in Fig. 11, the addition of isopropyl alcohol, benzoquinone, and ammonium oxalate decreases RhB degradation, suggesting that h+, ·OH, and ·O2− all play significant roles for the degradation of RhB over the Ag/Titanium Oxide composite. Moreover, the obvious decrease of the degradation efficiency after adding isopropyl alcohol indicates that hydroxyl radicals (·OH) are the main active species of the photocatalytic process of Ag/Titanium Oxide towards RhB.

Based on the results of scavengers, a possible mechanism was proposed for the degradation of RhB over the Ag/Titanium Oxide composite. The mechanism is illustrated in Fig. 12. Upon irradiation with visible light, electron-hole pairs are photoinduced in the metallic Ag nanoparticles due to the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect. The photogenerated electrons efficiently transfered to the conduction band (CB) of Titanium Oxide due to the Schottky barrier at the Ag/ Titanium Oxide interface. These electrons are subsequently trapped by oxygen molecules (O2), leading to the generation of superoxide radical ions (·O2−). Meanwhile, the holes present on the surface of the Ag nanoparticles not only directly oxidize pollutants but also oxidize water (H2O) to produce hydroxyl radicals (·OH). These reactive radical species play a crucial role in the oxidation of organic pollutants. Furthermore, the well-defined interfaces between Ag and Titanium Oxide facilitate rapid interfacial electron transfer, significantly reducing the recombination rate of photoinduced electrons and holes, as illustrated in Fig. 7b. This efficient charge separation enhances the photocatalytic activity of the system, making it more effective for environmental applications24,46.

The photocatalytic activity of the Ag/Titanium Oxide composite was also evaluated by removing other dyes such as direct red, congo red, and green malachite, and the results are presented in Fig. 13. As shown in this figure, Ag/Titanium Oxide has a high photocatalytic activity for the removal of different dyes under visible light irradiation.

Kinetic studies

The kinetic of RhB removal by Ag/Titanium Oxide photocatalyst has been evaluated. The graphs of concentration (C-C0) versus time (zero order), lnC/C0 versus time (first order), and 1/C-1/C0 versus time (second order) are shown in Fig. 14. Kinetic constants of RhB removal by Ag/Titanium Oxide sample are presented in Table 2. According to Table 2, the synthesized Ag/Titanium Oxide composite strongly adheres to pseudo-first-order kinetic behavior in photocatalytic studies.

Recyclability

The recyclability of photocatalysts is crucial for practical applications. Therefore, the photostability of the Ag/Titanium Oxide composite was investigated by cycle removal experiments of RhB under identical conditions. After each removal cycle, the Ag/Titanium Oxide was recovered by simple filtration, washed with distilled water, and dried at 80 °C. The removal results of RhB using the reused Ag/Titanium Oxide after four regeneration cycles are shown in Fig. 15. It was found that the removal efficiency of RhB partially decreased (about 12%) after four cycles of the experiment. This decrease can be attributed to the partial loss of catalyst mass during the washing process.

In the final stage, several similar works in the field of dye pollutant removal using Ag/TiO2 are referenced in Table 3. As can be seen, synthesized Ag/Titanium Oxide photocatalyst have shown better color removal performance than previous Ag/TiO2 photocatalysts in the literature.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a method to synthesize visible-light-active Ag-decorated Titanium Oxide NPs. Using a rotating electrode in the arc discharge method, and AgNO3 as the precursor for silver decoration, the Ag/Titanium Oxide Schottky junction was prepared. We found the optimal concentration of Ag (0.4 g), which gives the best photocatalytic activity, and found that the duration of UV exposure plays a crucial role in increasing the SBET of the prepared sample (Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h)). Photocatalytic degradation of RhB under visible light demonstrated remarkable efficiency and results showed 96% and 98% degradation by Ag/Titanium Oxide (2 h) and Ag/Titanium Oxide (10 h), respectively. The kinetic studies showed that the Ag/Titanium Oxide composite strongly adheres to pseudo-first-order kinetic behavior. Further investigation into the reaction mechanism via trapping tests confirmed that hydroxyl radicals are the main active species responsible for the photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B. These findings emphasize the potential of Ag/Titanium Oxide NPs for environmental remediation, offering a promising pathway for the development of advanced photocatalysts activated by visible light.

Data availability

Data availability statementsData is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Mahdi, C., Pratama, C. A. & Pratiwi, H. Preventive study garlic extract water (Allium sativum) toward SGPT, SGOT, and the description of liver histopathology on rat (Rattus norvegicus), which were exposed by rhodamine B. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 546 062015 (2019).

Schneider, J. et al. Understanding TiO2 photocatalysis: Mechanisms and materials. Chem. Rev. 114, 9919–9986 (2014).

Belko, N. et al. pH-Sensitive fluorescent sensor for Fe (III) and Cu (II) ions based on Rhodamine B acylhydrazone: sensing mechanism and bioimaging in living cells. Microchem J. 191, 108744 (2023).

Grčić, I. et al. Enhanced visible-light driven photocatalytic activity of Ag@ TiO2 photocatalyst prepared in Chitosan matrix. Catalysts 10, 763 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Fu, F., Li, Y., Zhang, D. & Chen, Y. J. N. One-step synthesis of Ag@ TiO2 nanoparticles for enhanced photocatalytic performance. Nanomaterials 8, 1032 (2018).

Sabir, A., Sherazi, T. A., Xu, Q. J. S. & Interfaces Porous polymer supported Ag-TiO2 as green photocatalyst for degradation of Methyl orange. Surf. Interfaces. 26, 101318 (2021).

Liu, M. et al. Selective oxidation of glycerol into formic acid by photogenerated holes and superoxide radicals. ChemSusChem 15, e202201068 (2022).

Fei, J. & Li, J. Controlled Preparation of porous TiO2–Ag nanostructures through supramolecular assembly for plasmon-enhanced photocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 27, 314–319 (2015).

Ohno, T., Sarukawa, K., Tokieda, K. & Matsumura, M. J. Morphology of a TiO2 photocatalyst (Degussa, P-25) consisting of anatase and rutile crystalline phases. J. Catal. 203, 82–86 (2001).

Park, H., Kim, H., Moon, G., Choi, W. J. E. E. & Science, E. Photoinduced charge transfer processes in solar photocatalysis based on modified TiO 2. Energy Environ. Sci. Technol. 9, 411–433 (2016).

Kitano, M., Matsuoka, M., Ueshima, M. & Anpo, M. J. Recent developments in titanium oxide-based photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. A. 325, 1–14 (2007).

Rasul, S. M., Saber, D. R. & Aziz, S. B. Role of titanium replacement with Pd atom on band gap reduction in the anatase titanium dioxide: First-principles calculation approach. Results Phys. 38, 105688 (2022).

Akakuru, O. U., Iqbal, Z. M. & Wu, A. TiO2 nanoparticles: Properties and applications. Appl. Nanobiotechnol. Nanomed., 1–66 (2020).

Ijaz, M. & Zafar, M. Titanium dioxide nanostructures as efficient photocatalyst: Progress, challenges and perspective. 45, 3569–3589 (2021).

Zhou, W. et al. Well-ordered large‐pore mesoporous anatase TiO2 with remarkably high thermal stability and improved crystallinity: Preparation, characterization, and photocatalytic performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 1922–1930 (2011).

Park, H., Park, Y., Kim, W., Choi, W. J. Surface modification of TiO2 photocatalyst for environmental applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 15, 1–20 (2013).

Liu, G., Jimmy, C. Y., Lu, G. Q. M. & Cheng, H. M. Crystal facet engineering of semiconductor photocatalysts: Motivations, advances and unique properties. Chem. Commun. 47, 6763–6783 (2011).

Busiakiewicz, A., Kisielewska, A., Piwoński, I. & Batory, D. J. The effect of Fe segregation on the photocatalytic growth of ag nanoparticles on rutile TiO2 (001). Appl. Surf. Sci. 401, 378–384 (2017).

Yu, J., Low, J., Xiao, W., Zhou, P. & Jaroniec, M. J. Enhanced photocatalytic CO2-reduction activity of anatase TiO2 by coexposed {001} and {101} facets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8839–8842 (2014).

Hirakawa, T. & Kamat, P. V. Charge separation and catalytic activity of Ag@ TiO2 core – shell composite clusters under UV – irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 3928–3934 (2005).

Lu, Q. et al. Photocatalytic synthesis and photovoltaic application of Ag-TiO2 Nanorod composites. Nano Lett. 13, 5698–5702 (2013).

Wang, X. et al. Highly active ag clusters stabilized on TiO2 nanocrystals for catalytic reduction of p-nitrophenol. Appl. Surf. Sci. 385, 445–452 (2016).

Maus, A., Strait, L. & Zhu, D. J. E.R. Nanoparticles as delivery vehicles for antiviral therapeutic drugs. Eng. Regen. 2, 31–46 (2021).

Joseph, A., Vijayanandan, A. Pharmacy Photocatalysts synthesized via plant mediated extracts for degradation of organic compounds: A review of formation mechanisms and application in wastewater treatment. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 22, 100453 (2021).

Li, G. et al. Review of micro-arc oxidation of titanium alloys: Mechanism, properties and applications. J. Alloys Compd. 948, 169773 (2023).

Tseng, K. H. et al. Preparation of Ag/Cu/Ti nanofluids by spark discharge system and its control parameters study. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015 694672 (2015).

Schumacher, B. M. After 60 years of EDM the discharge process remains still disputed. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 149, 376–381 (2004).

Nafar, L., Rasuli, R., FallahBarzoki, M. & Sajadi, M. Arc-Discharge synthesis of ZnO: Ag nanoparticles for photocatalytic applications: Effects of aging, microwave radiation, and voltage. 18, 2305–2314 (2023).

Yavari, S., Olaifa, K., Shafiee, D., Rasuli, R. & Shafiee, M. Molybdenum oxide nanotube caps decorated with ultrafine ag nanoparticles: Synthesis and antimicrobial activity. 647, 123528 (2023).

Torkaman, M., Rasuli, R. & Taran, L. Photovoltaic and photocatalytic performance of anchored oxygen-deficient TiO2 nanoparticles on graphene oxide. Results Phys. 18, 103229 (2020).

Sajadi, M. & Rasuli, R. J. P. A facile approach to distinct unusual sucrose in honey by titanium oxide nanoparticles. Plasmonics 17, 65–70 (2022).

Stein, M. & Kruis, F. E. Scaling-up metal nanoparticle production by transferred Arc discharge. Adv. Powder Technol. 29, 3138–3144 (2018).

Slotte, M. & Zevenhoven, R. Energy efficiency and scalability of metallic nanoparticle production using Arc/spark discharge. Energies 10, 1605 (2017).

Han, J., Zhou, Y., Li, Z., Chen, Y. & Zhang, Q. Effects of discharge current and discharge duration on the crater morphology in single-pulse Arc machining of Ti6Al4V. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., 1–15 (2024).

Shahzad, K. et al. Synergistic silver-titania nano-composites: Optimized hetero-junction for enhanced water decontamination. Desalin. Water Treat. 320, 100696 (2024).

Chen, C. Y. J. W., Pollution, S. & Air, & Photocatalytic degradation of Azo dye reactive orange 16 by TiO2. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 202, 335–342 (2009).

Min, Y. et al. Silver@ mesoporous anatase TiO2 core-shell nanoparticles and their application in photocatalysis and SERS sensing. Coatings 12, 64 (2022).

Kunthakudee, N. et al. Ultra-fast green synthesis of a defective TiO2 photocatalyst towards hydrogen production. RSC Adv. 14, 24213–24225 (2024).

Estrada-Vázquez, R. et al. Assessment of TiO2 and Ag/TiO2 photocatalysts for domestic wastewater treatment: Synthesis, characterization, and degradation kinetics analysis. Reaction Kinetics Mech. Catal. 137, 1085–1104 (2024).

Singh, A., Wan, F., Yadav, K., Kharbanda, S. & Thakur, P. A novel magnetic NiFe2O4-Ag-ZnO hybrid nanocomposite for the escalated photocatalytic dye degradation and antibacterial activities. Mater. Sci. Engineering: B. 299, 116935 (2024).

Nabi, G. et al. Green synthesis of spherical TiO2 nanoparticles using Citrus Limetta extract: Excellent photocatalytic water decontamination agent for RhB dye. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 129, 108618 (2021).

Gusmão, C. A. et al. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic VOC oxidation via Ag-loaded TiO2/SiO2 materials. J. Mater. Sci. 59, 1215–1234 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Surface plasma Ag-decorated Bi5O7I microspheres uniformly distributed on a zwitterionic fluorinated polymer with superfunctional antifouling property. Appl. Catal. B. 271, 118920 (2020).

Ji, M. et al. Oxygen defect modulating the charge behavior in titanium dioxide for boosting photocatalytic nitrogen fixation performance. Mater. Reports: Energy. 3, 100231 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Electrophoretic deposition of MXene coating on Mg alloy 2, 5 PDCA-LDH film for enhanced anticorrosion/wear. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochemical Eng. Aspects. 702, 135043 (2024).

Li, Q. Y. et al. Controllable preparation and photocatalytic performance of Hollow hierarchical porous TiO2/Ag composite microspheres. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochemical Eng. Aspects. 658, 130707 (2023).

Rodríguez-González, V., Hernández-Gordillo, A. Silver-based photocatalysts: A special class. Nanophotocatalysis Environ. Appl. Mater. Technol., 221–239 (2019).

Liang, H., Jia, Z., Zhang, H., Wang, X. & Wang, J. Photocatalysis oxidation activity regulation of Ag/TiO2 composites evaluated by the selective oxidation of Rhodamine B. Appl. Surf. Sci. 422, 1–10 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Li, J., Li, W. & Kang, D. J. M. Synthesis of one-dimensional mesoporous ag nanoparticles-modified TiO2 nanofibers by electrospinning for lithium ion batteries. Materials 12, 2630 (2019).

Yang, L. et al. Charge-transfer-induced surface-enhanced Raman scattering on Ag – TiO2 nanocomposites. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 16226–16231 (2009).

Michalska, M. et al. Effect of Ag modification on TiO2 and melem/g-C3N4 composite on photocatalytic performances. 13 5270 (2023).

Li, X., Hou, Y., Zhao, Q. & Chen, G. J. L. Synthesis and photoinduced charge-transfer properties of a ZnFe2O4-sensitized TiO2 nanotube array electrode. Langmuir 27, 3113–3120 (2011).

Takai, A., Kamat, P. V. Capture store, and discharge. Shuttling photogenerated electrons across TiO2–silver interface. 5, 7369–7376 (2011).

Cantarella, M. et al. Green synthesis of photocatalytic TiO2/Ag nanoparticles for an efficient water remediation. 443, 114838 (2023).

Zidane, Y. et al. Green synthesis of multifunctional MgO@ AgO/Ag2O nanocomposite for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and toluidine blue. Front. Chem. 10, 1083596 (2022).

Gang, R. et al., Size controlled Ag decorated TiO2 plasmonic photocatalysts for tetracycline degradation under visible light. 31, 102018 (2022).

Nguyen, T. H. et al. Green synthesis of a photocatalyst Ag/TiO2 nanocomposite using Cleistocalyx operculatus leaf extract for degradation of organic dyes. 306, 135474 (2022).

Shan, D. et al. Chemical synthesis of silver/titanium dioxide nanoheteroparticles for eradicating pathogenic bacteria and photocatalytically degrading organic dyes in wastewater. 30, 103059 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support from the University of Zanjan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Noor H. Abbas: Methodology, Investigation. Reza Rasuli: Writing, Supervision. Parvaneh Nakhostin Panahi: Writing, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbas, N.H., Rasuli, R. & Nakhostin Panahi, P. Decorated titanium oxide with Ag nanoparticles as an efficient photocatalyst under visible light: a novel synthesis approach. Sci Rep 15, 8207 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92864-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92864-2