Abstract

Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) have emerged as a fundamental approach within deep learning for the resolution of partial differential equations (PDEs). Nevertheless, conventional multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) are characterized by a lack of interpretability and encounter the spectral bias problem, which diminishes their accuracy and interpretability when used as an approximation function within the diverse forms of PINNs. Moreover, these methods are susceptible to the over-inflation of penalty factors during optimization, potentially leading to pathological optimization with an imbalance between various constraints. In this study, we are inspired by the Kolmogorov-Arnold network (KAN) to address mathematical physics problems and introduce a hybrid encoder-decoder model to tackle these challenges, termed AL-PKAN. Specifically, the proposed model initially encodes the interdependencies of input sequences into a high-dimensional latent space through the gated recurrent unit (GRU) module. Subsequently, the KAN module is employed to disintegrate the multivariate function within the latent space into a set of trainable univariate activation functions, formulated as linear combinations of B-spline functions for the purpose of spline interpolation of the estimated function. Furthermore, we formulate an augmented Lagrangian function to redefine the loss function of the proposed model, which incorporates initial and boundary conditions into the Lagrangian multiplier terms, rendering the penalty factors and Lagrangian multipliers as learnable parameters that facilitate the dynamic modulation of the balance among various constraint terms. Ultimately, the proposed model exhibits remarkable accuracy and generalizability in a series of benchmark experiments, thereby highlighting the promising capabilities and application horizons of KAN within PINNs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Partial differential equations (PDEs) mathematically describe the behavior of an unknown multivariate function and its partial derivatives. In recent years, physics-informed machine learning (PIML1,2) has risen as a formidable alternative to classical numerical methods for solving general nonlinear PDEs. The physics-informed neural networks (PINNs3,4) are a fascinating research direction in the field of PIML, which cleverly utilize quadratic penalty functions to fuse physical knowledge with neural network architectures and provide a novel perspective for solving PDEs.

Following the emergence of the PIML solution paradigm, PINNs have seen a series of notable advancements and innovations in various physical scenarios. These advances encompass architectures tailored for time-series-dependent problems5,6,7, novel formulations of objective functions8,9,10, as well as the recalibration of weights11,12,13 for multi-task learning (refer to section “Related works”). Nevertheless, prevailing methodologies continue to confront challenges, including challenges in interpretability stemming from conventional black-box networks, and issues pertaining to equilibrium in multi-constraint optimization, constituting the principal impetus for this inquiry. Concretely, our initial research motivation arises from the limitations of current network architectures regarding their interpretability, particularly in the context of decoding sequence models within high-dimensional latent spaces, where traditional neural networks are still considered opaque models and encounter difficulties in discerning interpretable signals among high-dimensional noise. Our second research motivation is rooted in the observation that disparate penalty terms within the quadratic penalty function induce an imbalance in the gradient of multiple objectives, which adversely impacts the training process of the model. Prior studies13,14 endeavored to allocate weight coefficients by initially setting higher penalty factors or by exploiting the gradient noise, yet these heuristic approaches remain plagued by deficiencies within the optimization process. We contend that the penalty factor should be ascertained through robust learning mechanisms instead of being linearly inflated as a hyperparameter. Considering these factors, our objective is to devise a novel neural solver that facilitates enhanced interpretability and optimization efficiency.

Upon examination of the design aspects of network architectures within PIML, regardless of whether they are derived from original formulations of PINNs or alternative advanced neural solvers13,15,16, it is observed that their fundamental components are multilayer perceptrons (MLPs17). While the universal approximation theorem18 ensures the nonlinear approximation potential of MLPs, enhancing the depth and parameter count of the network is often necessary to augment its capability for complex representations19, and it also suffers from the spectral bias problem20. Within MLPs, the affine function at each neuron node undergoes a nonlinear transformation by a uniformly applied activation function; this suggests that the nonlinear capability of MLPs is predominantly contingent upon intensive parameter optimization of the affine function weights rather than the intrinsic characteristics of the activation function. However, another important approximation theory, the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem21, states that any bounded multivariate function \(f:[0, 1]^{d}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) can be written as a linear combination of a finite number of continuous univariate functions \(\Phi _{i}: \mathbb {R} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}, \ \phi _{i,j}:[0,1] \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\), which is expressed as follows:

Nonetheless, these one-dimensional activation functions pose challenges in the learning process, as they often lack smoothness and continuity. To mitigate these issues, we draw inspiration from recent advancements in leveraging the Kolmogorov-Arnold network (KAN22) for exploring mathematical and physical problems, which was recently introduced to reformulate the approximation of multivariate functions as a combinatorial task of learning a series of univariate activation functions. These activation functions can be parameterized using B-spline functions23, which are located on edges rather than nodes in the computational graph and smoothly fit the target curve by dynamically learning the interpolated basis functions during training. Considering the outstanding potential of KAN in revealing white-box network research, it makes sense to effectively utilize KAN to bridge the gap between the sequence of the latent space and the physical output. Additionally, as posited by the Information Bottleneck (IB24,25) theory, the process of training deep learning models encompasses superfluous noise signals within the latent representation. Our research indicates that KAN efficiently decompose correlated feature signals within the latent space that are amenable to spline function interpolation with greater efficiency.

Regarding the optimization of the model, considering the constrained nature of PDEs, the penalty term based on the quadratic penalty function usually becomes pathologically optimized by the unreasonable expansion of the penalty factor, while the augmented Lagrangian function method can provide a more accurate optimization capability than the quadratic penalty function method, and the constraint violation degree is generally lower. Therefore, our study aims to achieve the following two core objectives: Firstly, we are dedicated to exploring novel approximation function representations and investigating how to incorporate traditional fitting algorithms to enhance the interpretability of the model, given the limitations of the MLP-based network structure regarding interpretability. Secondly, we reconstruct the loss function of PINNs to alleviate its pathological optimization problem during training and further improve the stability of the model. Our contributions can be summarized as follows:

-

We initially investigate the feasibility of integrating KAN into the PINNs framework and propose an innovative neural solver model. The model is designed using a hybrid encoder-decoder architecture. Specifically, the decoder in the proposed model incorporates the KAN, which maps the hidden variable features in the high-dimensional latent space into a series of trainable univariate activation functions, thereby efficiently capturing and learning the signal components suitable for spline function interpolation.

-

We identify that the main causative factor for the imbalance in the optimization of the quadratic penalty function in the PINNs framework is the rapid expansion of the penalty factor. This phenomenon leads to an increasing number of Hessian matrix conditionals for the loss function, which affects the stability of the optimization process. Therefore, we formulate the augmented Lagrangian function to reconstruct the loss function of the proposed model. The stability of the model during optimization is significantly improved by transforming the penalty factors and Lagrange multipliers associated with the penalty constraints into learnable parameters of the model.

-

The proposed model exhibits remarkable precision and robustness across various benchmark experiments, and its prediction accuracy is generally improved by one to two orders of magnitude. Compared to traditional neural networks, the KAN decoder learns the nonlinear activation function itself rather than just the weights of the affine function, which is closer to the nature of solving PDEs.

Related works

PIML for solving PDEs

The PINNs proposed by3, the first work to incorporate physical knowledge into a neural network architecture for solving the forward and backward problems of PDEs, provide a generalized paradigm for merging the constraints of PDEs into data-driven learning. However, PINNs still have many limitations and room for improvement, such as oversimplified network structures and unstable optimization methods. Roughly speaking, all variants of PINNs focus on developing better optimization objectives and neural architectures to improve the performance of PINNs1. Here, we summarize some of the current variants of PINNs.

Nerual architectures

Considering that the ability of MLPs alone to capture features was overly simplistic, Li et al. proposed a temporal iteration using the implicit multistep and Runge-Kutta approaches, and then approximated these iterative schemes with a fully connected neural network15. Bilgin et al. presented a two-stream deep model based on graph convolutional networks and feed-forward neural networks for learning lattice and graph representations derived from discretizations of PDEs domain26. Although these methods enhanced the characterization of single MLPs, they underperformed in capturing temporally correlated features. Since many real physical systems in physics depended on the evolution of time, sequence models were a reasonable way to represent these systems. Several studies6,7,27 have proposed training PINNs in conjunction with recurrent neural architectures like the long short-term memory (LSTM28) or the gated recurrent unit (GRU29). These methods alleviate the problem of cumulative errors in time series, but their loss functions still face the challenge of imbalance or instability during multi-objective optimization.

Novel optimization targets

Some researchers have proposed training PINNs with new objective functions instead of weighted summations of residuals. Jahani et al. proposed an enhanced PINNs with two-stage training8. The method accelerates the convergence of the model by first using boundary conditions to train some network weights, followed by training the weights of the operator constraints and updating the trained boundary weights. However, the method fails to adequately consider the overall balance between multi-constraint optimization. The Deep Ritz Method (DRM9) proposed to use the variational form of PDEs as a new objective function, thus avoiding the computation of higher-order derivatives. However, the DRM was only available for self-adjoint differential operators, thus limiting its applications. The gradient enhancement method10 optimized the training of PINNs by using the higher-order derivatives of the PDEs as regularization terms, although the method has difficulty balancing the effects of constraints between multiple gradients.

Loss reweighting

Physical systems described by PDEs often need to satisfy multiple constraints simultaneously. Direct optimization relying solely on the quadratic penalty function of PINNs will inevitably lead to the unbalanced problem of mismatched convergence speeds under different constraints. Many researchers have proposed loss-weighted or adaptive learning rate annealing methods by analyzing the training dynamics of PINNs from different perspectives. Wang et al. proposed an annealing algorithm with an adaptive learning rate that utilizes the statistical information of the gradient during model training to balance the interactions between different residual terms in the loss function11. Further, using Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK30) theory, Wang et al. demonstrated that PINNs have a spectral bias, making it difficult for them to converge to high-frequency components, thus proposing a learning rate annealing method12 based on NTK. However, these methods required additional computation of eigenvalues, which increased the cost of the computation. Furthermore, from the perspective of multi-objective optimization, some researchers have also proposed the use of maximum likelihood estimation to learn the Gaussian noise in training and thus adaptively adjust the weights of different constraint terms13. In addition to the improved methods based on PINNs mentioned above, researchers in another branch have focused on studying the mapping relationship between parameters and state variables and proposed approximation schemes based on neural operators31,32,33.

Kolmogorov-Arnold network

The foundational modules of modern deep learning are MLPs17. However, the deeply embedded structure and large parameter numbers of MLPs often result in issues like gradient vanishing or exploding, overfitting, and inadequate interpretability. Recently, Liu et al. proposed the KAN22, a novel network architecture that attempts to open the black-box structure of traditional networks, which possesses more precise and interpretable properties than MLPs and can serve as an excellent alternative to MLPs. The KAN is inspired by the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem21, which efficiently combines Kolmogorov networks34,35 and learnable activation functions36,37 and demonstrates impressive accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability in mathematical and physical science problems22. An increasing number of researchers have proposed using KAN to improve more explanatory deep learning models. Li et al. integrated KAN into U-Net38 to enhance medical image segmentation and generation39. Rubio et al. investigated the performance of KAN in a satellite traffic prediction task, emphasizing its potential as a powerful predictive analytics tool40.

In the field of solving PDEs, Wang et al. proposed to replace the traditional MLPs with KAN directly in the framework of PINNs and called it KINN for solving different forms of PDEs41. KINN verified experimentally that KAN outperforms the traditional methods in multi-scale problems, singularity problems, stress-concentration problems, and complex geometric problems. However, except for replacing MLPs, KINN offers relatively limited improvements for PINNs. Subsequently, Shukla et al. proposed using a combination of Chebyshev polynomials and the tanh function to improve the training stability of KAN, called cPIKAN42. Compared with PINNs, cPIKAN can achieve the same accuracy level while significantly reducing the number of network parameters, but its training process requires more GPU time. Howard et al. focused on the training cost of KAN and proposed a domain decomposition method for KAN, called FBKAN43. The method allows for the parallel training of multiple small KANs, thus providing an efficient solution for the training of multi-scale PDE problems. Furthermore, Jiang et al. combined KAN with PINNs to propose the KA-PINN model for solving two/three-dimensional incompressible fluid dynamics problems44. KA-PINN effectively reduces the computational complexity of high-dimensional flow field problems by utilizing the high-dimensional function decomposition characteristics of KAN, while also revealing the application potential of KAN in fluid mechanics simulations.

The main contribution of the above research is to explore the feasibility of replacing MLPs with KAN and the optimization of the choice of KAN activation function. In contrast, the research objective of our study aims to explore the role and function of KAN in complex combination architectures by designing a hybrid encoder-decoder architecture, which utilizes the decomposition characteristics of KAN to efficiently decode the high-dimensional features generated by the encoder. In addition, regarding the pathological optimization problem in PINNs, we utilize the augmented Lagrangian function to reconstruct the loss function and experimentally verify the constraint effect of the Lagrangian multiplier on the penalty factor, which significantly improves the optimization stability of the model.

Methodology

In this section, we introduce the comprehensive architecture and computational methods of the proposed model with the aim of enhancing the interpretability and accuracy of PINNs. Meanwhile, to address the impact of the penalty factor of the quadratic penalty function, we introduce the augmented Lagrangian function to reconstruct the loss function of the model.

Problem setup

In this study, we consider the constrained problem of PDEs with initial and boundary conditions as follows:

where \(\mathscr {N}, \mathscr {B}, \mathscr {I}\) denote the differential, boundary, and initial condition operators of the PDEs involving space x, time t, and their partial derivatives, respectively. The \(\mathscr {N}\) denotes hyperbolic, parabolic, or elliptic PDEs; the \(\mathscr {B}\) denotes the Dirichlet or the Neumann condition; f denotes the homogeneous or non-homogeneous term; and u(x, t) denotes the solution function to be solved. Furthermore, \(\mathscr {X} \in \mathbb {R}^{d}\), \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathbb {R}^{1}\), and \(\partial \mathscr {X} \in \mathbb {R}^{d}\) denote the spatial, temporal, and boundary domains, respectively. Equation (2) can be written in the weighted residual form as follows:

Traditional PINNs are designed to approximate the solution of Eq. (3) by employing deep MLPs, which are constructed as the quadratic penalty function for their loss function. They can be written as

and

where \(\circ\) denotes a composite process, W and \(\mu\) denote the weight parameters and activation function of each layer in the MLPs, and \(\sigma\) denotes the penalty factor. As previously shown, \(u_{nn}\) constructed by MLPs exhibits notable limitations regarding interpretability. As for function fitting, the affine transformations within MLP nodes do not inherently map onto the interpolating function, with the nonlinear characteristics being solely contingent upon a uniform global activation function. Moreover, PINNs employ the quadratic penalty function as the loss function \(\textrm{L}_{PINNs}\), which encounters the problem of infinite growth of the penalty factor during the optimization process. Accordingly, in subsection “AL-PKAN architecture”, we will detail the proposed neural solver intended to address the aforementioned challenges. Subsequently, in subsections “Impact of penalty factors in PINNs” and “Augmented Lagrangian function for AL-PKAN”, we will introduce the loss function limitations of PINNs and the proposed model’s enhancements to these.

AL-PKAN architecture

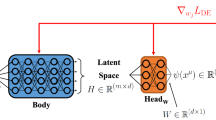

The comprehensive architecture of the proposed model is depicted in Fig. 1, incorporating a two-stage encoder-decoder framework integrating the GRU29 and the KAN22 modules. Initially, the GRU module conducts sequence modeling on the original inputs, capturing long-range dependencies and encoding them into a high-dimensional latent space. Subsequently, within the latent space, the KAN module undertakes fine-grained decoding, decomposing the signal amenable to spline-based interpolation from the signal containing hidden variables and noise. It further decomposes the multivariate function within the latent space into a series of linearly combined univariate activation functions, parametrically represented through the learnable coefficients \(c_{i}\) of the B-spline function. Finally, the model employs the augmented Lagrangian function from subsection “Augmented Lagrangian function for AL-PKAN” as the objective loss function. We name the proposed model AL-PKAN (Augmented Lagrangian Physics-informed Kolmogorov-Arnold Network), which means the Physics-informed Kolmogorov-Arnold Network that fuses the augmented Lagrangian function. Specifically, the AL-PKAN model contains encoder and decoder modules as follows:

An overview of AL-PKAN architecture: (a) The GRU module is utilized for long-range dependency modeling of input sequences. The module can capture the interdependent features of the input sequences and encode these information into a high-dimensional latent space, providing a rich sequence of features for the subsequent decoding process. (b) The KAN is utilized to perform fine-grained decoding in latent space. The module is responsible for decomposing high-dimensional signals into signal components suitable for spline interpolation. In this decoding process, the multivariate functions in the latent space are decomposed into a series of linear combinations of learnable univariate activation functions, which constitute the edges of the computational graph and are represented by parameterized B-spline functions. (c) The loss function of the proposed model is reconstructed by the augmented Lagrangian function, where the Lagrangian multipliers and penalty factor are learnable parameters. This approach effectively utilizes a finite penalty factor to approximate the optimal solution, which avoids the pathological problem of the traditional quadratic penalty function due to the rapid expansion of the penalty factor.

-

Encoder: The input sequences of PDEs are generated by the random sequence sampling approach45, assuming the input sequence at moment t is \(X_{t} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times d}\), \(Y_{t} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times r}\) denotes the output sequence, d and r denote the input and output dimensions of the PDEs, respectively, and n denotes the number of samples in a batch. The short-term and long-term dependent features in the input sequence can be captured by reset gates \(R_{t} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times q}\) and update gates \(Z_{t} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times q}\), respectively, which can be written as

where \(W_{xr},W_{xz},W_{xh} \in \mathbb {R}^{d \times q}\) and \(W_{hr},W_{hz},W_{hh} \in \mathbb {R}^{q \times q}\) are weight parameters, \(b_{r},b_{z},b_{h} \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times q}\) are bias parameters, \(\tilde{H}_{t} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times q}\) denotes the candidate hidden state, and q denotes the number of hidden units. Finally, the hidden state \(H_{t} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times q}\) can be encoded by a convex combination of \(H_{t-1}\) and \(\tilde{H}_{t}\), which can be written as

-

Decoder: The role of the decoder is to map the sequence of hidden features obtained from the encoding back into the physical space to generate the corresponding output sequence. Traditional design approaches usually employ other recurrent neural networks or the Transformer model46 based on self-attention mechanisms. However, the underlying architectures of these network models are commonly constructed based on MLPs, which leads to models that are overly dependent on learning the weight parameters of affine functions during training and lack interpretability at the physical level. Inspired by the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem21 and the KAN22 modeling concept, we decided to design the KAN as a decoder to receive the encoded state. In the encoded latent space, the sequence of hidden variable features decomposed through the KAN module is transformed into a linear combination of the B-spline functions, thus generating the physical output by spline interpolation. The calculation can be written as follows:

where \(\Psi\) denotes the learnable parameterized activation function expressed as

where \(\beta\) denotes a linear combination of parameterized B-spline functions. The nonlinear function \(\rho\) is introduced to increase the smoothness of the B-spline function, similarly to the design of residual networks47, which can be defined as

where \(W_{\psi }\) is the learnable parameter that absorbs the dynamic coefficients \(c_{i}\) of the \(\beta\) and is initialized by the Kaiming initialization48, and the k-th order basis function for the i-th control point is denoted as \(B_{i,k}\), which can be calculated recursively by the Cox-deBoor formula23 as follows:

where the definition domain of the basis function contains m equal intervals of nondecreasing vectors \([g_{0},g_{1},..., g_{m}]\), these basis functions are efficiently fitted to univariate functions by linearly combining to obtain smooth curves.

Furthermore, we can depict the optimization landscape of the entire proposed network with the following Lipschitz constant:

where \(\upsilon _{max}(\cdot )\) denotes the maximum absolute eigenvalue of the matrix, and \(L_{G},L_{K}\) and \(W_{G},W_{\psi }\) denote the layers and learnable parameters of the encoding and decoding modules, respectively. \(\text {Lip}(\cdot )\) denotes the calculation of the Lipschitz constant for the current model. Analyzing the Lipschitz constants of each module in the network is one of the important means to research the stability of network optimization, which can effectively quantify potential problems such as gradient vanishing and gradient explosion. If the Lipschitz constant of a module in the network is too large or tends to diverge, it may lead to instability of the entire network. Equation (12) indicates that the proposed model exhibits excellent optimization stability with no divergence in the Lipschitz constants of both the encoder and decoder. For the AL-PKAN model, the gating technique used in the encoding module mitigates the gradient explosion problem caused by the long-range dependency, while the spline function and residual design used in the decoding module can effectively prevent the gradient from vanishing. Lipschitz continuity is more general than continuous differentiability. Therefore, analyzing the Lipschitz constants of each module and even the entire network is also an effective approach to understanding network properties (interested readers can refer to49,50). Additionally, KAN employs the smooth B-spline combination as the basis function for function interpolation, which is similar to the finite element method (FEM51) that relies on the combination of shape functions, as presented in the Appendix “Similarities between KAN and FEM”. This similarity reveals the rationality of considering KAN as a decoder in the latent space, since they both aim at approximating complex functional morphology through linear combinations of basis functions, thus enabling a highly accurate decoding process. Subsequently, recognizing that the quadratic penalty function suffers from penalty factor inflation, the loss function of the proposed model will be analyzed and reconstructed to enhance its robustness and optimization efficiency.

Impact of penalty factors in PINNs

From the constrained optimization perspective, a generic equationally constrained optimization problem on \(\mathbb {R}^{d}\) can be described as

where \(J, h_{i}\) are continuous real-valued functions on \(\mathbb {R}^{d}\), J is the objective function to be optimized, and \(h_{i}\) serves as equational constraints for the optimization problem. In the paradigm of PIML for solving PDEs, typical solving frameworks (such as PINNs3) transform the PDEs problem in Eq. (2) into the constrained problem in Eq. (13), which can be expressed as

where \(h_{\mathscr {B}}\) and \(h_{\mathscr {I}}\) denote the continuous functions satisfied by the corresponding equational constraints, and \(\Omega = (\mathscr {X} \times \mathscr {T}) \in \mathbb {R}^{d+1}\) and \(\partial \mathscr {X} \in \mathbb {R}^{d}\) denote the spatio-temporal and boundary domains of the PDEs, respectively. Assume that the solution function u of the PDEs is continuous and differentiable. \(u_{nn}\) denotes a neural solver defined in the parameter space \(\theta \in \Theta\), whose approximation ability is guaranteed by the generalized approximation theorem 18. When solving Eq. (14), the numerical value of the objective function must be decreased without violating the constraints. Therefore, PINNs are solved by constructing the penalty function as the loss function \(\textrm{L}_{\sigma }\) to be optimized, thus transforming the constrained problem into an unconstrained problem 52, which can be written as

where \(\sigma > 0\) denotes the penalty factor for positive real numbers. However, we can easily get that the stability of PINNs optimization tends to be affected by the penalty factor \(\sigma\). Assuming that \(\theta ^{*}\) denotes the optimal solution of Eq. (15) and \(\varepsilon\) denotes the set of indicators for the equation constraints, the KKT condition of Eq. (14) is written as

where \(\lambda _{i}^{*}\) denotes the optimal multiplier of the corresponding constraint. In addition, the KKT condition for Eq. (15) is as follows:

When Eqs. (16) and (17) converge to the same point (\(\theta = \theta ^{*}\)), it can be introduced by comparing their gradient expressions

where \(\lambda _{i}^{*}\) is fixed. To satisfy all the equational constraints, the penalty factor \(\sigma\) during the optimization process gradually increases and tends to infinity. In addition, consider that the Hessian matrix of \(\textrm{L}_{\sigma }\) can be written as

where L denotes the Lagrangian function of penalty function \(\textrm{L}_{\sigma }\). We observe that \(\nabla _{\theta \theta }^{2}\textrm{L}_{\sigma }\) is approximated as the sum of a fixed-valued matrix and a matrix with maximum eigenvalues tending to positive infinity. This structure leads to an increasing condition number for \(\nabla _{\theta \theta }^{2}\textrm{L}_{\sigma }\). Therefore, viewed from the perspective of the KKT condition and the number of Hessian matrix conditions, these risk factors both increase the challenge of PINNs in the optimization process 11,12. Based on the consideration of these aspects, we introduce a more stable optimization approach in next subsection to further improve the optimization performance of the proposed model.

Augmented Lagrangian function for AL-PKAN

The Eq. (18) illustrates that the numerical optimization process for PINNs becomes more difficult as the penalty factor expands dramatically. In this study, we propose to re-solve Eq. (14) with the augmented Lagrangian function, which can be written as

where \(\lambda _{\mathscr {B}} \in \mathbb {R}^{n_{b}}\) and \(\lambda _{\mathscr {I}} \in \mathbb {R}^{n_{b}}\) denote the Lagrangian multipliers of the boundary and initial conditions of the PDEs, respectively. Those variables are a set of vectors of length \(n_{b}\), with \(n_{b}\) denoting the total number of training samples that satisfy the corresponding constraints, and the \(\langle \cdot \rangle\) denotes the inner product operation. To demonstrate that solving Eq. (14) is equivalent to solving Eq. (20), we introduce the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Let \(\theta ^{*}, \lambda _{i}^{*}\) be the local minimum solution of Eq. (14) and the corresponding Lagrangian multipliers, and with LICQ and second-order sufficiency conditions holding at \(\theta ^{*}\), there exists a finite constant \(\bar{\sigma }\) such that for any \(\sigma \ge \bar{\sigma }\), \(\theta ^{*}\) is also a strict local minimal solution of \(\textrm{L}_{\lambda }\).

Proof

Denote the Lagrangian function of Eq. (14) as follows

Since \(\theta ^{*}\) is a local minima of \(\textrm{L}\) and the second-order sufficient condition is held, there are

where v is an arbitrary nonzero vector. The first-order gradient of \(\textrm{L}_{\lambda }\) is written as

Since \(h_{i}(\theta ^{*}; x)=0\), the following relation can be obtained

Consider the second-order gradients of \(\textrm{L}\) and \(\textrm{L}_{\lambda }\) are written as follows

and

To prove that \(\theta ^{*}\) is a strict local minimum of \({L}_{\lambda }\), one needs to demonstrate that the following inequality holds for sufficiently large \(\sigma\). i.e.,

Adopting the counterfactual approach, assume that Eq. (27) does not hold, then for an arbitrarily large \(\sigma\), there exists \(||v_{k}||=1\) and satisfies

Then

Since \(\{v_{k}\}\) is a bounded sequence, there must exist a clustering point, set to v, then

This contradicts Eq. (22); therefore, the conclusion is valid.

Conversely, if \(\theta ^{*}\) satisfies \(h(\theta ^{*}; x) = 0\) and is a local minima of \(\textrm{L}_{\lambda }(\theta ,\lambda ^{*},\sigma ^{*}; x)\), then for any feasible point \(\theta\) that is sufficiently close to \(\theta ^{*}\), there are

Therefore, the \(\theta ^{*}\) is a local minima of Eq. (14).

The above lemma effectively demonstrates that Eq. (20) has a more accurate optimization search capability than Eq. (15). The instability caused by large values of the penalty factor \(\sigma\) can be effectively avoided by utilizing the approach, and the restriction of locally convex structures is not required53. Contrary to traditional numerical iterative algorithms54,55, the optimization process of the proposed model is non-convex. We use Eq. (20) as the novel loss function for the neural solver, which means that the Lagrangian multipliers \(\lambda\) and the penalty factor \(\sigma\) can be jointly regarded as learnable parameters that can be updated by the backward propagation algorithm56. Here are the updated rules:

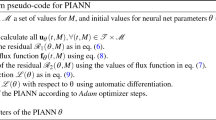

where \(\alpha _{\lambda }\) and \(\alpha _{\sigma }\) are the predefined learning rates for \(\lambda\) and \(\sigma\), respectively, which are independent of the parameters \(\theta\) of the neural solver. As a result, the proposed model can be described as Algorithm 1.

Numerical experiments

In this section, four PDEs of varying complexity are selected as benchmark experiments to compare the relative error results of AL-PKAN with other physical information-based optimization algorithms. Subsequently, the significant advantages of using KAN in the proposed model are highlighted by conducting ablation experiments, which incorporate different neural solvers, KAN layers and loss functions. All computations are carried out on a single Nvidia RTX 3060 Ti GPU with 16GB memory.

AL-PKAN is more accurate than physical information penalty methods

-

Experimental Setup: We demonstrate the excellent performance of the proposed AL-PKAN by comparing the numerical experimental results of several benchmark equations using some existing physical information penalty methods as baselines. These benchmark equations and details of their loss functions are provided in the Appendix “Benchmark equations in experiments”. We utilize the Sobol sequence algorithm45 to generate training datasets that satisfy operator constraints and boundary constraints, respectively. The algorithm generates sequences that are independent in all dimensions and significantly improves their uniform distribution properties by using prime numbers as the base of the generating matrix. Here, the size of the sequences \(n_{d}\) engaged in unsupervised learning (satisfying operator constraints) is set to 5000, and the size of the sequences \(n_{b}\) engaged in supervised learning (satisfying initial and boundary constraints) is only set to 256, which is also a small sample learning strategy. The training steps for the proposed model are shown in the Algorithm 1. Then we evaluate the numerical inference merits of the experiments on the validation dataset with relative \(L^2\) error (\(||\hat{y} - y||_{L^2} /{||y||_{L^2}}\)), where \(\hat{y}\) denotes the predicted value of the model and y denotes the analytical solution or the conventional numerical solution. The hyperparameter configuration of the proposed model and comparison methods is described in detail in Appendix “Hyperparameters,” and the computational cost analysis of the proposed model in the training and inference phases is shown in Appendix “Computational cost.”

-

Baselines: To validate the accuracy and generalization of the proposed AL-PKAN model in solving the benchmark equations, several methods based on PINNs and their improvements were selected for comparison. These models consist of the feedforward network of extended PINNs to integrate Lagrangian functions from58, the dual-stream deep learning model from26, and the NTK eigenvalue-based gradient calibration technique from12. The key metric for evaluating these models is the performance of the relative \(L^2\) errors on the benchmark equations.

-

Results: Figure 2 intuitively displays the comparison results of the predicted solutions of the proposed AL-PKAN model with the exact solutions in four benchmark experiments. Among these, the linear PDEs field functions shown in Fig. 2a and c are periodic and smooth; the nonlinear PDEs field function shown in Fig. 2d also has smooth characteristics, while the nonlinear PDEs field function shown in Fig. 2b exhibits sharp transition behavior at \(x=0\). We can clearly observe that the AL-PKAN model can effectively capture the periodic or local discontinuous behavior of the PDEs and exhibit excellent numerical prediction accuracy, whether for continuous field functions or field functions with shock behavior. In addition, Fig. 3 further shows the distribution of the absolute point-by-point error between the AL-PKAN predicted solution and the exact solution. The results show that AL-PKAN can effectively balance different constraints, which significantly reduces the degree of constraint violation during training. Table 1 summarizes the relative \(L^{2}\) errors of the proposed AL-PKAN and the other benchmark methods on the four benchmark equations. According to the results shown, the AL-PKAN model performs the best in the relative \(L^2\) error of numerical prediction compared to the other benchmark methods3,12,26,58, which on average improves the prediction accuracy by one or two orders of magnitude. We observe that although the AL-PINNs model proposed in 58 integrates Lagrangian functions, the network structure based on MLPs still suffers from limitations in feature representation. For the design of the loss function, although the approach treats the Lagrange multiplier \(\lambda\) as a sequence of learnable parameters, it fixes the penalty factor \(\sigma\) as a hyperparameter. As shown in Eq. (20), the penalty constraint term is controlled by both \(\lambda\) and \(\sigma\). As \(\lambda\) converges, \(\sigma\) is restricted to a relatively bounded range, which avoids the problem of the infinite expansion of \(\sigma\) in the quadratic penalty function. However, if \(\sigma\) remains a fixed hyperparameter, it fails to be effectively regulated by the learning of \(\lambda\), which makes it difficult to achieve an optimal balance in minimizing the constraint term and consequently affects the prediction accuracy of the model. Therefore, unlike the loss function strategy of AL-PINNs, our proposed AL-PKAN model treats \(\sigma\) as a learnable parameter and balances multiple constraints by exploring its optimal value during the optimization process. Moreover, AL-PKAN employs a hybrid encoder-decoder of GRU and KAN as the approximation function instead of MLPs in AL-PINNs. On the other hand, the two-stage hybrid model proposed in 26 performs poorly for numerical decoding accuracy, although it has enhanced feature extraction capability. NTK 12 relies on the precise tuning of the uniformity of the eigenvalue matrix distribution, and it remains unavoidably affected by the potential for spectral bias in MLPs. These results explicitly demonstrate that the AL-PKAN model exhibits significant advantages in numerical decoding accuracy and effectively reduces the degree of constraint violations compared to those methods that rely on MLPs and quadratic penalty functions. Figure 4 shows the frequency statistics of the best multiplier sequences learned \(\lambda ^{*}\) by AL-PKAN when reaching the best generalization error on the validation set. These sequences act on different constraints, and their values indicate the degree of constraint violation for different input samples. We can observe that almost all of the \(\lambda ^{*}\) are centered around the zero point and exhibit roughly centrosymmetric properties, which suggests that the multiplicative terms can effectively control the neural solver parameters during the learning process of the model and keep those from breaking the original constraints. Moreover, according to Eqs.(16) and (23), when they both converge to the same optimal parameter \(\theta ^{*}\), the optimal multiplier \(\lambda ^{*}\) satisfies: \(\lambda ^{*} \leftarrow \lambda - \sigma \nabla _{\theta } h_{i}(\theta ^{*}; x)\). When the training process stabilizes, i.e., \(\nabla _{\theta } h_{i}(\theta ^{*}; x)\) tends to zero, \(\lambda ^{*}\) also converges to a stable value. As shown in Algorithm 1, the initial value of \(\lambda\) is set to a sequence of all zeros, i.e., assuming that the penalty terms in the loss function all satisfy the constraints. During training, \(\lambda\) gradually converges to an approximately normal distribution as shown in Fig. 4, indicating that the model can effectively regulate samples that violate constraints, thereby achieving a balance between multiple penalty constraints. The learning process of the penalty factor \(\sigma\) in all benchmark experiments is shown in Fig. 5. We can observe that \(\sigma\) is almost incremental throughout the training, which is consistent with the update rule of \(\sigma\) in the classical discretization iteration methods 59,60. Meanwhile, the optimal penalty factor \(\sigma ^{*}\) that makes AL-PKAN achieve the best generalization result is sufficiently large and bounded, which further demonstrates that the learnable \(\lambda\) can effectively constrain the expansion rate of \(\sigma\). However, \(\sigma ^{*}\) also fluctuates with factors such as learning rate or random seeds, and there is still room for improvement in terms of \(\sigma\) being ‘large enough’. Figure 6 provides the relative \(L^{2}\) error of prediction of the proposed AL-PKAN on the validation dataset of all benchmark experiments during the training process. To facilitate a more discernible elucidation of the process employing the IB theory, we deflated the vertical coordinates of Fig. 6 to the logarithmic scale. We observe that the neural gradients of AL-PKAN on the validation dataset undergo a phase transition from high to low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR24), which corresponds to a fitting phase of high gradient agreement and a diffusion phase when the gradient fluctuations dominate the signal. In the fitting phase, the AL-PKAN model is fitted rapidly by the gradient information corresponding to the high SNR, thus reducing the relative \(L^{2}\) error, while in the diffusion phase, the SNR of the AL-PKAN model is in a stochastic regime, which gradually converges to the optimal generalized model.

The frequency histogram statistics show the optimal Lagrangian multipliers \(\lambda ^{*}\) in all benchmark experiments. Where the Helmholtz equation contains \(\lambda ^{*}_{1}\), the Burgers equation contains \(\lambda ^{*}_{1},\lambda ^{*}_{2}\), the Black-Scholes equation contains \(\lambda ^{*}_{1},\lambda ^{*}_{2},\lambda ^{*}_{3}\), and the Klein-Gordon equation contains \(\lambda ^{*}_{1},\lambda ^{*}_{2},\lambda ^{*}_{3}\).

Dynamic relative \(L^{2}\) error evolution of the AL-PKAN model on the validation dataset of all benchmark experiments. Fitting phase: the model undergoes the usual rapid transition from high to low SNR. Diffusion phase: since the SNR is in the stochastic regime, the model converges slowly on the logarithmic scale.

The advantages of KAN in AL-PKAN

-

Experimental Setup: As previously established, the incorporation of the KAN module within the proposed AL-PKAN has demonstrated significant advantages in enhancing the predictive accuracy and generalizability of the model. To explore the impact of different configurations on the performance of the proposed model, we designed a series of ablation experiments. All experiments used the Helmholtz equation as the test benchmark, and the relative \(L^{2}\) error and mean square error (MSE) results under each experimental configuration were recorded separately.

-

The impact of using different neural solvers: To further verify the contribution of the KAN module to the prediction accuracy of the proposed model, we designed various network architectures to serve as the encoder and decoder of the neural solver, respectively, to systematically evaluate their performance. The evaluated network architectures comprised MLPs integrated with residual connections, independent GRU, independent KAN, and cross-combinations between them. As listed in Table 2, this ablation analysis facilitates a more tangible understanding of KAN’s pivotal role within the proposed model and underscores the importance of enhancing its interpretability.

-

The Number of KAN Layer: The purpose of this ablation analysis is to evaluate the effects of varying the quantity of KAN layers on the model’s inferential capabilities, further examining the capacity of the KAN to transition from shallow to deeper layers in terms of fitting proficiency. As illustrated in Table 3, we adjusted the count of KAN layers, ranging from one to five.

-

The impact of using different loss functions: To systematically evaluate the performance of different loss functions in AL-PKAN, we compare the behavior of various loss function strategies from existing research13,58,61. Xiang et al. proposed a noise sampling approach based on Gaussian probabilistic models for dynamically assigning loss weights to adaptively adjust the training balance of the model13; Maddu et al. utilizes the gradient variance as a rationale for loss term balancing, aiming to optimize the convergence performance of the model by reducing the variance between different loss terms61. In addition, we compare the performance of two augmented Lagrangian functions as loss functions: one with a fixed constant penalty factor (AL-PINNs58 proposed by Son et al.) and the other with a learnable penalty factor (Our proposed AL-PKAN).

-

Results: The experimental results in Table 2 illustrate that the GRU exhibits the best encoding ability for the encoder, while the decoding performance of the KAN is significantly better than other components. Specifically, the prediction effect of the MLP+MLP combination is the worst, while the performance of the GRU+KAN combination is the best. The prediction accuracy of the optimal combination generally improves by one to two orders of magnitude. When the KAN module is replaced by other components, the prediction performance of the model decreases significantly. For example, in the GRU+MLP experiment, the results indicate that MLPs significantly underperform KAN in the decoding task. Specifically, MLPs achieve nonlinear mapping by learning the weight relationship of the affine function, whose nonlinear property relies on a globally uniform activation function. In contrast, KAN constructs a more flexible framework of learnable activation functions by learning linear combinations between activation functions, which significantly improves the the performance of the model in the decoding task. In addition, KAN performs better in decoding the sequence of hidden variables than in encoding the sequence of features, which further validates the rationality of the AL-PKAN architecture design. The AL-PKAN can decompose multivariate functions in high-dimensional latent spaces into a series of linear combinations of univariate B-spline functions by effectively using the KAN module. This process enables AL-PKAN to extract signal components that are more suitable for spline function interpolation, which significantly improves the interpretability and nonlinear fitting ability of the model. The outcomes in Table 3 show that the three layers of KAN configuration produce optimal performance. These results also confirm that the two-layer structure of the original Kolmogorov-Arnold representation may be poorly fitted due to the univariate functions appearing to be non-differentiable or fractal, although its nonlinear approximation ability can be effectively improved by simply stacking the layers of the KAN. The experimental results in Table 4 compare the performance of different loss function optimization strategies. Specifically, both methods can alleviate the pathological problems in the optimization process of the penalty function to some extent by introducing a learnable normal noise as a balancing factor for the penalty term or dynamically updating the balancing factor of the penalty term using the gradient variance. However, neither of these methods is as effective as the loss function strategy based on augmented Lagrangian function reconstruction. Although both AL-PINNs and AL-PKAN reconstruct the loss function using an augmented Lagrangian function, the network structure of the approximation function of the two methods is significantly divergent. In addition, AL-PINNs fix the penalty factor \(\sigma\) as a hyperparameter, weakening the constraining effect of the Lagrange multiplier \(\lambda\), which makes it difficult to find the optimal penalty factor to balance multiple constraints. In contrast, AL-PKAN treats \(\sigma\) as a learnable parameter and effectively constrains the growth of \(\sigma\) through \(\lambda\), which significantly improves the optimization performance. Meanwhile, Fig. 7 also presents the loss history curves of different loss function strategies, where the loss values have been logarithmically scaled. The experimental results show that the strategy based on the augmented Lagrangian function can significantly accelerate the decrease of the loss function in the training initial stage, which indicates that the Lagrangian multiplier \(\lambda\) can effectively punish samples that violate constraints. Compared with AL-PINNs, proposed AL-PKAN exhibits lower training loss errors, which further verifies the advantage of treating the penalty factor \(\sigma\) as a learnable parameter. This design allows \(\sigma\) to dynamically adjust to a more appropriate position under the constraint of \(\lambda\), which more effectively balances the relationship between multiple constraints and significantly improves optimization performance.

The comparison of the training loss trajectories for each loss function strategy shown in Table 4.

Conclusions

This study extensively investigates the application potential of KAN within PIML and proposes a hybrid encoder-decoder deep learning model termed AL-PKAN. To efficiently solve the numerical solutions of PDEs, the proposed model first encodes the original input signals into a high-dimensional latent space using the GRU. Subsequently, the latent space is decoded using the KAN to finely extract the signals suitable for spline interpolation from the hidden variable sequences and noise signals. Furthermore, to surmount the optimization constraints inherent in PINNs’ quadratic penalty functions, the model integrates an augmented Lagrangian function to reconstruct its loss function, effectively constrained by the inflationary impact of the penalty factor during the optimization process. We numerically evaluated the proposed model in several benchmark experiments of different complexity. The results confirm that the proposed model exhibits excellent accuracy and generalization in solving different forms of PDEs’s numerical solutions. These outcomes also highlight the importance of exploring KAN in PIML and foreshadow that KAN will be the cornerstone of AI for PDEs, since KAN is more in line with the nature of solving PDEs.

Furthermore, for more complex PDEs, especially in high-dimensional cases, the traditional Monte Carlo approximation method usually only samples at a finite number of selected sample points, which inevitably falls into the inherent defects of scattered optimization. To overcome this challenge, we believe that the region-based optimization paradigm is a worthy direction for further research62. This theory extends the optimization from discrete points to their neighborhood regions and combines trust region calibration strategies to effectively control the gradient estimation error introduced during sampling. Meanwhile, the current optimization based on PINNs mainly relies on the alternating use of first-order optimization methods and the proposed Newton method, but these optimizers often face problems such as local minima and degenerate saddle points when dealing with highly nonlinear and nonconvex lossy surfaces. Therefore, exploring more efficient and reliable second-order optimization strategies (such as the Pseudo-Newton method with Wolfe line search conditions63) is also a significant research direction. We will continue to investigate these tasks in future work.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Karniadakis, G. E. et al. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 422–440 (2021).

Cuomo, S. et al. Scientific machine learning through physics-informed neural networks: Where we are and what’s next. J. Sci. Comput. 92, 88 (2022).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Zou, Z., Meng, X. & Karniadakis, G. E. Correcting model misspecification in physics-informed neural networks (pinns). J. Comput. Phys. 505, 112918 (2024).

Zhang, Z. & Wang, Q. Sequence-to-sequence stacked gate recurrent unit networks for approximating the forward problem of partial differential equations. IEEE Access 12, 61795–61809 (2024).

Ren, P., Rao, C., Liu, Y., Wang, J.-X. & Sun, H. Phycrnet: Physics-informed convolutional-recurrent network for solving spatiotemporal pdes. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 389, 114399 (2022).

Lu, Z., Guo, C., Liu, M. & Shi, R. Remaining useful lifetime estimation for discrete power electronic devices using physics-informed neural network. Sci. Rep. 13, 10167 (2023).

Jahani-Nasab, M. & Bijarchi, M. A. Enhancing convergence speed with feature enforcing physics-informed neural networks using boundary conditions as prior knowledge. Sci. Rep. 14, 23836 (2024).

Yu, B. The deep ritz method: a deep learning-based numerical algorithm for solving variational problems. Commun. Math. Stat. 6, 1–12 (2018).

Yu, J., Lu, L., Meng, X. & Karniadakis, G. E. Gradient-enhanced physics-informed neural networks for forward and inverse pde problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 393, 114823 (2022).

Wang, S., Teng, Y. & Perdikaris, P. Understanding and mitigating gradient flow pathologies in physics-informed neural networks. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 43, A3055–A3081 (2021).

Wang, S., Yu, X. & Perdikaris, P. When and why pinns fail to train: A neural tangent kernel perspective. J. Comput. Phys. 449, 110768 (2022).

Xiang, Z., Peng, W., Liu, X. & Yao, W. Self-adaptive loss balanced physics-informed neural networks. Neurocomputing 496, 11–34 (2022).

Chen, Y., Lu, L., Karniadakis, G. E. & Dal Negro, L. Physics-informed neural networks for inverse problems in nano-optics and metamaterials. Opt. Express 28, 11618–11633 (2020).

Li, Y., Zhou, Z. & Ying, S. Delisa: Deep learning based iteration scheme approximation for solving pdes. J. Comput. Phys. 451, 110884 (2022).

Hoidn, O., Mishra, A. A. & Mehta, A. Physics constrained unsupervised deep learning for rapid, high resolution scanning coherent diffraction reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 13, 22789 (2023).

Cybenko, G. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Math. Control Signals Syst. 2, 303–314 (1989).

Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M. & White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 2, 359–366 (1989).

Yarotsky, D. Error bounds for approximations with deep relu networks. Neural Netw. 94, 103–114 (2017).

Wang, S., Wang, H. & Perdikaris, P. Learning the solution operator of parametric partial differential equations with physics-informed deeponets. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi8605 (2021).

Braun, J. & Griebel, M. On a constructive proof of Kolmogorov’s superposition theorem. Construct. Approx. 30, 653–675 (2009).

Liu, Z. et al. Kan: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.19756 (2024).

Smith, P. W. A practical guide to splines (carl de boor). SIAM Rev. 22, 520 (1980).

Anagnostopoulos, S. J., Toscano, J. D., Stergiopulos, N. & Karniadakis, G. E. Learning in pinns: Phase transition, total diffusion, and generalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.18494 (2024).

Saxe, A. M. et al. On the information bottleneck theory of deep learning. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2019, 124020 (2019).

Bilgin, O., Vergutz, T. & Mehrkanoon, S. Gcn-ffnn: A two-stream deep model for learning solution to partial differential equations. Neurocomputing 511, 131–141 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y. & Shen, T. Physical information-guided multidirectional gated recurrent unit network fusing attention to solve the black-scholes equation. Digital Signal Process. 156, 104766 (2025).

Van Houdt, G., Mosquera, C. & Nápoles, G. A review on the long short-term memory model. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 5929–5955 (2020).

Zhao, R. et al. Machine health monitoring using local feature-based gated recurrent unit networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 65, 1539–1548 (2017).

Jacot, A., Gabriel, F. & Hongler, C. Neural tangent kernel: Convergence and generalization in neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 31 (2018).

Lu, L., Jin, P., Pang, G., Zhang, Z. & Karniadakis, G. E. Learning nonlinear operators via deeponet based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 218–229 (2021).

Zanardi, I., Venturi, S. & Panesi, M. Adaptive physics-informed neural operator for coarse-grained non-equilibrium flows. Sci. Rep. 13, 15497 (2023).

Diab, W. & Al Kobaisi, M. U-deeponet: U-net enhanced deep operator network for geologic carbon sequestration. Sci. Rep. 14, 21298 (2024).

Schmidhuber, J. Discovering neural nets with low Kolmogorov complexity and high generalization capability. Neural Netw. 10, 857–873 (1997).

Sprecher, D. A. & Draghici, S. Space-filling curves and Kolmogorov superposition-based neural networks. Neural Netw. 15, 57–67 (2002).

Khagi, B. & Kwon, G.-R. A novel scaled-gamma-tanh (sgt) activation function in 3d CNN applied for MRI classification. Sci. Rep. 12, 14978 (2022).

Fakhoury, D., Fakhoury, E. & Speleers, H. Exsplinet: An interpretable and expressive spline-based neural network. Neural Netw. 152, 332–346 (2022).

Zhang, S. & Zhang, C. Modified u-net for plant diseased leaf image segmentation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 204, 107511 (2023).

Li, C. et al. U-kan makes strong backbone for medical image segmentation and generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02918 (2024).

Vaca-Rubio, C. J., Blanco, L., Pereira, R. & Caus, M. Kolmogorov-arnold networks (kans) for time series analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.08790 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Kolmogorov arnold informed neural network: A physics-informed deep learning framework for solving pdes based on kolmogorov arnold networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11045 (2024).

Shukla, K., Toscano, J. D., Wang, Z., Zou, Z. & Karniadakis, G. E. A comprehensive and fair comparison between mlp and kan representations for differential equations and operator networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02917 (2024).

Howard, A. A., Jacob, B., Murphy, S. H., Heinlein, A. & Stinis, P. Finite basis kolmogorov-arnold networks: domain decomposition for data-driven and physics-informed problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.19662 (2024).

Jiang, Q. & Gou, Z. Solutions to two-and three-dimensional incompressible flow fields leveraging a physics-informed deep learning framework and kolmogorov-arnold networks (Int. J. Numer. Meth, Fl, 2025).

Renardy, M., Joslyn, L. R., Millar, J. A. & Kirschner, D. E. To sobol or not to sobol? The effects of sampling schemes in systems biology applications. Math. Biosci. 337, 108593 (2021).

Han, K. et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 87–110 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. Residual networks of residual networks: Multilevel residual networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 28, 1303–1314 (2017).

Narkhede, M. V., Bartakke, P. P. & Sutaone, M. S. A review on weight initialization strategies for neural networks. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55, 291–322 (2022).

Bottou, L., Curtis, F. E. & Nocedal, J. Optimization methods for large-scale machine learning. SIAM Rev. 60, 223–311 (2018).

Gouk, H., Frank, E., Pfahringer, B. & Cree, M. J. Regularisation of neural networks by enforcing lipschitz continuity. Mach. Learn. 110, 393–416 (2021).

Taylor, C. A., Hughes, T. J. & Zarins, C. K. Finite element modeling of blood flow in arteries. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 158, 155–196 (1998).

Han, S. P. & Mangasarian, O. L. Exact penalty functions in nonlinear programming. Math. Program. 17, 251–269 (1979).

Bertsekas, D. P. Multiplier methods: A survey. Automatica 12, 133–145 (1976).

Butcher, J. C. A history of runge-kutta methods. Appl. Numer. Math. 20, 247–260 (1996).

Taylor, C. A., Hughes, T. J. & Zarins, C. K. Finite element modeling of blood flow in arteries. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 158, 155–196 (1998).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323, 533–536 (1986).

Zhou, P., Xie, X., Lin, Z. & Yan, S. Towards understanding convergence and generalization of adamw (IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach, Intell, 2024).

Son, H., Cho, S. W. & Hwang, H. J. Enhanced physics-informed neural networks with augmented lagrangian relaxation method (al-pinns). Neurocomputing 548, 126424 (2023).

Rockafellar, R. T. Augmented lagrangians and applications of the proximal point algorithm in convex programming. Math. Oper. Res. 1, 97–116 (1976).

Yang, L., Sun, D. & Toh, K.-C. Sdpnal+: a majorized semismooth newton-cg augmented lagrangian method for semidefinite programming with nonnegative constraints. Math. Program. Comput. 7, 331–366 (2015).

Maddu, S., Sturm, D., Müller, C. L. & Sbalzarini, I. F. Inverse Dirichlet weighting enables reliable training of physics informed neural networks. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 3, 015026 (2022).

Wu, H., Luo, H., Ma, Y., Wang, J. & Long, M. Ropinn: Region optimized physics-informed neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14369 (2024).

Kiyani, E., Shukla, K., Urbán, J. F., Darbon, J. & Karniadakis, G. E. Which optimizer works best for physics-informed neural networks and kolmogorov-arnold networks? arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.16371 (2025).

Yang, X., Ge, Y. & Zhang, L. A class of high-order compact difference schemes for solving the burgersąŕ equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 358, 394–417 (2019).

Roul, P. & Goura, V. P. A new higher order compact finite difference method for generalised black-scholes partial differential equation: European call option. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 363, 464–484 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study is funded in part by the Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects under Grant 202401AW070019, 202101BE070001-008 and 202301AV070003, in part by the Youth Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62201237, in part by the Major Science and Technology Projects in Yunnan Province under Grant 202202AD080013 and 202302AG050009. (Corresponding author: Qingwang Wang.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing-original draft: Z.Z.; Methodology: Z.Z, W.Q; Software: Z.Z, W.Q; Writing-Review and Editing: W.Q, Z.Y; Resources: S.T, Z.W; Supervision: W.Q, S.T. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Reprints and permissions information

is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Similarities between KAN and FEM

Equation (9) describes the activation function of KAN, which contains the B-spline function and the residual term. For simplicity, we first ignore the residual term that increases the smoothness and consider the following B-spline function with \(B_{i}\) as the basis function.

where k and G denote the order and grid size, respectively, and \(c_{i}\) are the learnable coefficients. Relatively, a one-dimensional linear finite element with G elements can be written as

where \(N_{i}\) is the shape function in finite elements, and \(k_{i}\) is the iterable displacement of the node. If we consider the usual cubic B-spline function (\(k=3\)) in the interval \([-1, 1]\) and maintain the same grid size, for \(-1 \le x < 0\):

Relatively, consider a cubic element of the FEM with the shape function described as

Assuming that \(u_{kan}(x) = u_{fem}(x)\) for \(-1 \le x < 0\), i.e.,

then

The relationship can be obtained as follows:

then

Similarly, for \(0 \le x < 1\), \(B_{i}\) can be written as

Similar to Eq. (39), the following relationship can be obtained:

By comparing Eqs. (40) and (42), we can establish the following relationship between the learnable coefficients \(c_{i}\) of KAN and the iterative displacement \(k_{i}\) of FEM:

Although our comparison object only includes the shallow KAN and the FEM, which uses a simple shape function, it reveals that they are similar in terms of function fitting. We can compare the linear combination of B-spline functions used by KAN to the combination of shape functions in FEM, highlighting the fact that KAN is essentially closer to the approximation process for solving PDEs.

Benchmark equations in experiments

Helmholtz equation

The two-dimensional Helmholtz PDEs is expressed as follows:

where \(k=1, a_{1}=1, a_{2}=4\), and it has the analytic solution \(u(x,y) = \sin (\pi x)\sin (4\pi y)\). The loss function of the proposed model can be reconstructed as

Burgers equation

The studied Burgers equation is defined as:

where \(v=\frac{1}{100 \pi }\), and the analytical solution is accessible at64. The loss function is reconstructed as follows:

Black-Scholes equation

The studied Black-Scholes equation is transformed into a non-degenerate and time-forward form as follows:

with the boundary conditions:

the analytic solution of this equation is presented by65 and its loss function is reconstructed as

Klein-Gordon equation

We consider the Klein-Gordon equation as follows:

where \(f, g_{1}, g_{2}, h\) and the analytic solution are presented by11, the loss function of this equation is reconstructed as

Hyperparameters

For the hyperparameters used for all benchmark experiments in section “Numerical Experiments”, we test the parameter learning rate \(\alpha _{\theta }\) of the proposed model from \(\{10^{-2},10^{-3},10^{-4}\}\) and the learning rate of the Lagrangian multipliers \(\alpha _{\lambda }\) and penalty factor \(\alpha _{\sigma }\) from \(\{10^{0},5 \times 10^{-1}, 1 \times 10^{-1}, 5 \times 10^{-2}, 1 \times 10^{-2}, 5 \times 10^{-3}, 1 \times 10^{-3}, 5 \times 10^{-4}, 1 \times 10^{-4} \}\), respectively. Table 5 shows our chosen optimal learning rates. The remaining hyperparameters in Algorithm 1 are set to \(k=3, G=10, n_{d}=5000, n_{b}=256, N=50000\), respectively.

For the baseline algorithms, we refer to the optimal hyperparameter settings provided in their respective works. Table 6 details the network structure and related parameter configurations. Combining the experimental results in Tables 1 and 6, we can observe that the proposed model can achieve higher prediction accuracy with fewer parameters (including the number of network layers and neurons). These results further verifie that although the time complexity of KAN (\(\mathscr {O}(N^2LG)\), where N represents the number of neurons, L represents the network depth, and G represents the interval of the spline function interpolation) is higher than MLPs (\(\mathscr {O}(N^2L)\)), the number of neurons N required by KAN is usually much less than MLPs41. Compared with other methods, the number of learnable parameters of AL-PKAN is reduced by 35%–84%, which not only significantly reduces the parameter cost but also achieves more excellent generalization performance.

In addition, Fig. 8 demonstrates the effect of GRU as an encoder on the prediction performance of the proposed model with various combinations of hyperparameters. Using the grid search technique, we evaluate the performance of the GRU for the combination of the history steps \(s \in \{1, 3, 5\}\), the number of network layers \(l \in \{1, 2, 4\}\), and the number of hidden units \(n \in \{50, 64, 100\}\). In numerical experiments with the four benchmark equations, we observe that smaller s, l, and n can significantly improve the prediction performance of the proposed model (e.g., \(s=3, l=2, n=64\)), which suggests a positive effect on the subsequent decoding process. This result further indicates that in hybrid architectures with KAN as the decoder, the encoder can achieve efficient encoding without relying on excessively learnable parameters.

Computational cost

Table 7 provides a detailed report of the training cost and inference cost of the AL-PKAN model. Considering that the training cost of KAN is usually higher42, in order to fairly compare the computational cost difference between KAN and MLPs, we replace KAN with MLPs only in the proposed AL-PKAN and record the training cost and inference cost of MLPs in Table 8. The experimental results show that the training cost of MLPs is lower than KAN, while the inference cost is higher than KAN. This phenomenon is mainly due to the simpler and easy-to-train network structure of MLPs, while KAN requires the calculation of the basis functions in each training iteration, which increases the training cost. However, MLPs depend on a larger number of learnable parameters to achieve sufficient fitting ability, while KAN reduces the number of learnable parameters by about \(35\%\) compared to MLPs and improves the prediction accuracy by one to two orders of magnitude in the meantime. This result further highlights the significant advantages and application potential of KAN in hybrid architectures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Wang, Q., Zhang, Y. et al. Physics-informed neural networks with hybrid Kolmogorov-Arnold network and augmented Lagrangian function for solving partial differential equations. Sci Rep 15, 10523 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92900-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92900-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Integrating Spectral Methods with Neural Network Architectures: A Review of Hybrid Approaches to Solving Differential Equation

Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering (2025)