Abstract

In the quest for sustainable construction solutions, this study explores the thermal insulation potential of sawdust as an eco-friendly material for building applications in hot-arid climates, with a focus on Iraq. The research evaluates the thermal behavior of sawdust when mixed with clay and glue, forming two different composite insulation materials. Laboratory experiments were conducted to measure thermal conductivity, with results compared against traditional insulators like Styrofoam. The sawdust-clay composite (20% sawdust + 80% clay) demonstrated a significantly lower thermal conductivity of 0.44 W/m K, outperforming the sawdust-glue mixture, which recorded 2.2 W/m K at its optimal ratio (80% sawdust + 20% glue). Experimental setups using three test rooms insulated with Styrofoam, sawdust-clay, and sawdust-glue materials were installed on the rooftop of a building in Kirkuk, Iraq, to assess energy efficiency under real climatic conditions. Over 22 days of testing under varying weather conditions (cloudy, rainy, and sunny), the sawdust-clay insulated room reduced power consumption by up to 37% compared to the uninsulated baseline. The sawdust-clay material maintained consistent insulation performance with negligible change in thermal conductivity, while the sawdust-glue composite exhibited a 63% increase in conductivity after prolonged exposure to fluctuating temperatures. These findings suggest that the sawdust-clay mixture is a viable, low-cost alternative for sustainable building insulation, contributing to energy savings and environmental preservation. This innovative approach addresses the dual challenge of managing wood waste and reducing the energy footprint of buildings in hot-arid regions. Future research could expand on the long-term durability and scalability of sawdust-based insulation in diverse climate zones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Effective air conditioners use 70–80% of total energy usage in hot-arid climatic zones; thus, lowering dependence on them will have a significant influence on energy consumption. Because of the fast construction of new structures, especially in emerging nations like Iraq, increased energy demand is estimated to be more significant, while adopting energy-saving technology is often overlooked1,2,3,4,5. Heat transfer occurs due to temperature differences, causing heat to move to or from a specific body. The greater the temperature difference, the more heat is transferred. This transfer can occur through conduction in solids, convection in fluids, or radiation at high temperatures. The amount of heat transferred can be reduced by placing barriers in the heat flow path. These barriers are known as heat-insulating materials, defined as materials or groups of materials with low thermal conductivity, used to prevent heat flow to and from a specific body6. Construction insulation is a fundamental and effective energy-saving technology applicable in domestic, residential, and industrial settings7,8,9. It reduces heat transmission to the environment, helping to maintain desired temperatures indoors10,11. In Iraq, insulation is crucial for minimizing high heating and cooling costs during summer and winter12,13. Wood serves as a natural heat insulator due to its low thermal conductivity, aided by air pockets and pores in its cellulose structure. Additionally, wood waste, including sawdust—a by-product of cutting wood—can be effectively utilized across various industries, providing a sustainable resource for insulation14. Sawdust has been used in construction for many years; it is lightweight and easy to carry, and each tree from which sawdust is produced has different chemical and physical properties15. Every city has factories and wood shops; thus, huge amounts of sawdust are produced daily. These are usually thrown away, burned, or buried16,17. Burning sawdust can harm the environment by releasing gases that contribute to global warming. Additionally, when accumulated, sawdust creates a polluting burden, further impacting ecological health18. When dumped into rivers and streams, they cause water pollution and harm aquatic organisms. They can also be carried and transported by air currents to cover the soil surface and thus cause harm to plants19,20. Climate change challenges can be mitigated by using building materials that incorporate wood components like sawdust. For over forty years, concrete containing sawdust has been utilized in construction. Additionally, sawdust is employed in brick structures, as well as in floors and walls21,22. Concrete, of which sawdust is the main component, has been used in building structures for more than forty years. Sawdust is also used in brick structures, floors, and walls23. For instance, wood-cement composite panels, lightweight concrete blocks, sustainable pavements, and precast concrete elements. Each material exhibits varying thermal insulation capacities based on its thermal conductivity coefficient. Building materials with a thermal conductivity of less than 0.07 W/K are classified as thermal insulating materials24. When comparing wood to other building materials, it has been observed that wood has a lower thermal conductivity, especially those with lower density and lower moisture levels25. Numerous studies have explored the potential of using wood and wood industry residues, such as sawdust, as thermal insulators. These materials help reduce heat transfer to and from buildings, thereby decreasing energy consumption within them. Three building materials were prepared by mixing sawdust, cement, and sand in different ratios: 1:1:1, 2:1:1, and 3:1:1. The 1:1:3 mixture had a lower thermal conductivity than the rest of the ratios because it contained a higher proportion of sawdust26. Chen Ding et al.27 developed a high-performance fireproof insulation mortar, highlighting the benefits of incorporating silica fume. Notably, the mortar with 10% silica fume shows a 28.30% reduction in mass loss and a 14.73% increase in compressive strength after high-temperature exposure. The ideal raw material ratio for the mortar is cement: (1) aggregate: 1.67, water: (2) dispersible emulsion powder: 0.045, fly ash: 0.15, diabase rock powder: 0.225, AOS foaming agent: 0.035, gelatin: 0.02, and silica fume: 0.138. Chen Ding et al.28 examine basalt fiber as an additive to enhance foam thermal insulation mortar, addressing its low bond strength. Results show that 1.5% basalt fiber optimally improves crack resistance, bond strength, and fire resistance, reducing mass loss by 11.1% and increasing compressive strength by 9.71% after high temperatures. Additionally, this new formulation is cost-effective, lowering production costs by up to 38.96% compared to existing materials while also offering a shorter economic recovery period, thereby supporting environmental sustainability and economic viability.

Hesham et al.29 have shown that it is possible to improve the sound and thermal insulation properties of concrete by adding sawdust to it, provided that it is protected from damage caused by moisture and water by appropriate treatment. Ibrahim et al.30 examined the use of non-zeolite rocks and sawdust to produce environmentally friendly bricks. By applying uniaxial dry pressure and firing temperatures of 950–1250 °C for three hours, they prepared samples. The results indicated that incorporating 8% sawdust into zeolite-poor rocks reduced the density from 1.6 to 1.45 g/cm3, increased porosity from 31 to 37.37%, and decreased compressive strength from 14.5 to 6.7 MPa. The study confirmed the feasibility of using zeolite-poor rocks combined with sawdust as sustainable building materials. Eboziegbe and Mizi Fan31 use sawdust, waste paper, and conventional gypsum to make the Wood-Crete material. The findings revealed that lightweight sustainable bricks with densities ranging from 356 to 713 kg/m3 and compressive resistance varying from 0.06 to 0.80 MPa can be created with acceptable insulation and other essential qualities for housebuilding. Sara Pava and Rosanne Walker32 investigated improvements in the thermal performance of historic buildings to enhance energy efficiency. Their study examined materials such as thermal paint, aerogel, cork and hemp lime, calcium silicate board, wood fiberboard, and PIR board. The U-value of a brick wall with lime plaster (approximately 840 mm) was measured at 1.32 W/m2 K. While thermal paint showed no effect, all other interior insulation materials reduced the U-value of the wall by 34% to 61%. Morales-Conde et al.33 examined blended wood shavings and sawdust from wood waste in various ratios to assess material properties. Findings indicated that increased wood waste lowered both density and Shore C hardness. Additionally, higher proportions of wood waste significantly reduced heat conductivity, with a more pronounced effect in compounds containing wood shavings compared to those with sawdust. Specifically, a 40% increase in wood waste led to a 61% reduction in flexural strength for sawdust samples (S40) and a 65% reduction for wood shavings samples (WS40). Clement Lacoste et al.34 use sodium alginate as a glue binder for biocomposites made from wood and fabric waste. For different wood/textile waste ratios, several aldehyde-based crosslinking agents (glyoxal, glutaraldehyde) were examined. The results show that for an average density of 308–333 kg/m3, the biocomposite is insulating with a thermal conductivity of 0.078–0.089 W/m K. Wisal Ahmed et al.35 examined sawdust as a sand substitute, using conventional NWC with sawdust contents of 0, 5, 10, and 15% and LWC with sawdust contents of 0% and 10% of the total dry volume of sand. The results of the tests revealed that increasing the proportion of sawdust reduced volumetric shrinkage and concrete density while increasing water absorption. An energy study of a single-room model constructed with sawdust formulations indicated a significant reduction in HVAC energy consumption and CO2 emissions. In a related experiment, Cetiner and Shea36 examined bio-based natural fiber products made from wood waste, including hemp, cork, cotton, and wood fiber. The results revealed that the thermal conductivity values of wood debris with varying thicknesses ranged from 0.048 to 0.055 W/m K. These values are slightly higher than those of commonly used conventional insulation materials. Si Zou et al.37 analyzed the material’s thermal and mechanical capabilities, water resistance, and microstructure; three primary factors were evaluated to establish the material’s appropriate percentage. Wetting water to biomass mass ratio (WW/B ratio), H2O2 to adhesive mass ratio (H/A ratio), and biomass to adhesive mass ratio (B/A ratio) were the three variables studied. With heat conductivity of 0.112 to 0.125 W/m K and compression strength of 0.76 to 0.71 MPa, the composite materials with WW/B ratios of 1 to 2, H/A ratios of 0.012 to 0.015, and B/A ratios of 0.12 were found to be the best. The research by Charai et al.38 and Pei et al.39 explores the potential of sawdust-based materials in sustainable construction. In “Thermal performance and characterization of a sawdust-clay composite material,” Charai and colleagues investigate the thermal properties and structural characteristics of a sawdust-clay composite, demonstrating its low thermal conductivity and favorable mechanical properties, making it a promising eco-friendly insulation solution for energy-demanding regions. Meanwhile, Pei et al., in "Preparation and characterization of ultra-lightweight ceramsite using non-expanded clay and waste sawdust", focus on developing an ultra-lightweight ceramsite from non-expanded clay and waste sawdust. Their study details the preparation process and characterizes the resulting material, which exhibits excellent lightweight properties and adequate strength, positioning it as a viable construction material. Together, these studies highlight the significance of repurposing waste materials like sawdust to create sustainable building solutions that enhance energy efficiency and promote environmentally friendly practices.

In reviewing the existing literature, several limitations become evident. Many studies on the use of wood chips and clay primarily focus on mechanical properties, often overlooking critical factors such as thermal performance and environmental impact. Additionally, there is significant variability in the types and proportions of binders and additives used, which leads to inconsistent results and makes it challenging to draw general conclusions. Furthermore, a lack of long-term performance data limits our understanding of the durability of wood chip-clay mixtures under varying environmental conditions. Most notably, there is a scarcity of field studies that evaluate the practical applications of these materials in real-world construction settings. Investigating standardized material compositions could establish a more consistent framework for future studies. Additionally, conducting long-term durability studies will provide valuable insights into the performance of these mixtures over time. Finally, implementing pilot projects that utilize wood chip-clay mixtures in actual construction could help assess their practicality and effectiveness in real-world applications. However, existing research mainly focuses on its mechanical properties in concrete mixes or eco-friendly bricks, leaving a gap in understanding its potential as a thermal insulator for exterior walls. This study aims to explore the thermal behavior of sawdust when mixed with clay and glue, seeking to develop a low-cost, sustainable insulation material that can reduce construction costs and enhance energy efficiency. This study aims at sustainable construction and energy-efficient building design:

-

1.

It focuses on two innovative formulations: sawdust mixed with clay and sawdust mixed with glue. By exploring various ratios of these mixtures, the research identifies optimal compositions that significantly reduce thermal conductivity, providing an eco-friendly alternative to conventional insulators like Styrofoam.

-

2.

Evaluates the thermal performance of these sawdust composites under real-world conditions, using experimental setups that simulate the hot-arid climate of Iraq.

-

3.

Reduce energy consumption in buildings, lower construction costs, and support the adoption of green building technologies, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions facing extreme climatic conditions.

Experimental methods

Preparation and test samples

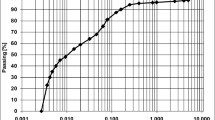

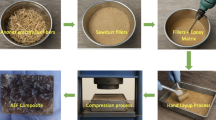

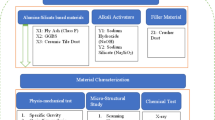

Figures 1 and 2 show a photographic view of the steps of manufacturing two samples of insulation materials (A and B). Sample (A) is sawdust and glue bricks with different proportions (80% sawdust + 20% glue) and (60% sawdust + 40% glue) (see Fig. 1). Sample (B) is sawdust and clay bricks with different proportions (20% sawdust + 80% clay) and (40% sawdust + 60% clay). Water was used as a main auxiliary material to form the two samples (clay bricks), as shown in Fig. 2. The dimensions of the two samples are 10 cm in length, 10 cm in width, and 2 cm in thickness.

After (3–6) days, the two samples were left to dry, and the thermal conductivity tests of the samples were carried out in the Mechanical Testing and Thermal Analysis Laboratory at the Technical Institute of Kirkuk, Iraq, as shown in Fig. 3. The results of the laboratory test for both samples are shown in Table 1. To know the thermal behavior of the proposed samples, the thermal conductivity values of the two samples were compared with other values for some traditional insulation materials. As shown in Table 2. From this table, it is noted that the thermal conductivity coefficient of the proposed chips is close to that of traditional thermal insulators such as cork and Styrofoam, which are considered among the most important and famous thermal insulation materials. Styrofoam is a brand of closed-cell extruded polystyrene foam (XPS), commonly called blue board, which is manufactured as an insulating board for buildings, walls, roofs, and foundations as a thermal insulator. Due to the strong atomic bonds, Styrofoam is a very stable material, and because of this stability, the plastic resists acids, bases, and water40,41. Therefore, it may cause a problem for human and animal life on land and at sea. Unlike sawdust, which has many useful uses.

Test room models

The experimental work was installed on the rooftop of the laboratory of the Department of Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning Technology Engineering, Northern Technical University. This work was carried out at the selected weather conditions and operating factors of Kirkuk, Iraq, Latitude 35.19°N, Longitude 44.31°E, during January 2021, during 8 h from 09:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The station has been directed in the south direction. A 220V electric lamp with electric power (100 watts) was installed inside the test room to be a source of heat energy. To ensure that the heat transfers in one direction from the light bulb to the southern wall, therefore, the other sides (eastern, western, the northern walls, floor, and roof) were covered with a composite layer of thermal insulation, which consists of the MDF board with 1.8 cm thick and the MDF board with 0.4 cm thick, and between them there is a layer of air 2 cm thick. The sixth southern wall (wall under study) consists of a plate of aluminum (0.09 cm thick), on whose outer surface different thermal insulators are installed, as shown in Fig. 4.

To study the thermal behavior of the thermal insulation materials (traditional and proposed), they have been installed on the south wall and tested under different weather conditions. The experimental station consisted of three test rooms with dimensions of (50 cm length, 50 cm width, and 50 cm height), in addition to a measurement and control system. In the first room (R1), the thermal insulation material was from the foam type (Styrofoam); in the second room (R2), the thermal insulation material was from the type (20% sawdust + 80% clay); and in the third room (R3), the thermal insulation material was from the type (80% sawdust + 20% glue), as shown in Fig. 5.

Compressive strength test

A 2000 kN ALFA tester was used to test the compressive strength, as shown in Fig. 6. tests were conducted at different ages of 7, 14, and 28 days, and three cubes were tested for each age.

Measurement and control system

A measurement and control circuit is designed to control the operation of the heat source inside the test room to determine the amount of heat loss across the south wall of each room, as shown in Fig. 7. The control system consists of a temperature control board with a microelectronic NTC high-precision thermostat and temperature sensor. The control board is fed by 12 V. Its main function is to adjust the temperature inside the room by installing a thermocouple with a metal bulb at the top of the room at a height of 45 cm. When the temperature inside the room reaches the required degree (such as \(32^\circ \text{C}\)), the control board sends a signal to open the electrical circuit feeding the heat lamp (turn off), and vice versa when the temperature drops below 32 °C (turn on the heat lamp). To calculate the average hourly energy consumed inside the test room (heating load), a Digital Watt Meter Power Energy kWh Meter with CT Coil has been used. The CT Coil is used to measure the amount of current supplied to the heat lamp. All components of the control circuit were placed inside a plastic box (PVC) with dimensions (1.5 × 1.5 × 7 cm) as shown in Fig. 7.

A digital K-type thermocouple thermometer 4-channel was used to measure the temperatures at different points in the test room. Thermocouples have been calibrated according to specifications and for a temperature range between 0 and 100 °C.

Governing equation

The south wall was analyzed using the exact solve method to calculate the overall heat transfer coefficient (U), the amount of heat loss across it, and estimate the amount of energy required to be provided inside the conditioned space.

Heat transfer through the composite wall

One of the most fundamental foundations on which any air conditioning system is designed is the thermal characteristics of the building structure. The heat energy is transferred from the inside building to the outside in the winter and vice versa in the summer in two ways: the first is across the building structure to the ambient air, and the second is by the infiltration of air through cracks and openings around doors and windows. Therefore, to reduce the rate of heat transfer through the structure, we must improve the thermal properties of the structure and reduce air leakage through cracks and openings across doors and windows. The French scientist J.B. Fourier was the first to develop heat transfer by conducting in one direction, as shown in the following equation:

where \(\left( {\frac{dQ}{{d\theta }}} \right)\) represents the rate of heat transfer per unit time, (A) the surface area of the section through which the heat transfer in units \({(\text{m}}^{2})\), (dt) the temperature difference in units \((^\circ{\rm C} )\), (dx) the length of the path through the material through which the heat transfer in units (m), and (K) the coefficient of thermal conductivity in the unit \(\left( {\frac{{\text{W}}}{{{\text{m}}\;{\text{k}}}}} \right)\).

The rate of heat transfer is inversely proportional to the thickness of the material, and if the temperature changes with time, therefore, the heat transfer is called an unsteady state, but if the temperature doesn’t change with time, the heat transfer is called a steady state, and the quantity (dQ/do) becomes constant and denoted by (q) and in units (watt). As for the negative sign in Eq. (2), it means that the temperature moves from the higher temperature side to the lower temperature side. So the equation becomes as follows:

To calculate the heat transfer through the composite walls, it used the principle of thermal resistance (R); therefore, Eq. (2) can be rearranged as follows:

where (R) is the thermal resistance in units of (K/W).

In the case of a composite wall (a construction wall consisting of several materials), where the heat flows in a stable state at a constant rate through the adjacent parts of the wall, there is also an additional resistance resulting from a thin layer of air (the air adjacent to the wall from the inside and outside), which tries adhesion to the wall and impedes the transfer of heat, and the thickness of this layer depends on the conditions of heat transfer by convection and whether it is natural or forced and the shape, roughness, and inclination of the surface. The heat transfer coefficient across the thin film layer is indicated by the letter (f), its units (W/m2 k), and its thermal resistance.

It is customary when calculating the heating load that a general value is given for the internal coefficient of heat transfer by convection (fi) considering the velocity of interior air is zero (static), and two values are given for the external coefficient of heat transfer by convection (fo) depending on the wind velocity and the season (summer or winter) as follows43:

Air with zero velocity | fi = 9.37 W/m2 k |

|---|---|

Winter-winds at 24 km/h | fo = 34.1 W/m2 k |

Summer-winds at 24 km/h | fo = 22.7 W/m2 k |

A general equation for the thermal resistance of any composite wall can be written as follows:

The reciprocal of the total thermal resistance is known as the overall heat transfer coefficient (W/m2 k) as follows:

Therefore, the rate of heat loss across the composite structure of the building can be calculated as follows:

Results and discussion

Compression test results

Sawdust is classified as a type of natural fiber. It is known that the use of this type of fiber causes an increase in the amount of voids and gaps in the sample structure, which leads to a decrease in compressive resistance. Sawdust is considered a weak type of raw material, and therefore increasing the amount of this mixture means a decrease in the sample’s resistance to pressure and thus an increase in the degree of deformation that occurs in the tested models. Also, the use of sawdust in the sample increases the mixture’s need for water, which means an increase in the ratio of water to clay and thus a decrease in compressive resistance. Table 3 shows the technical specifications of the compression testing device. Therefore, many studies have aimed to improve the properties of clay bricks using wood industry waste. The most important concern of researchers is the compressive strength of sawdust samples with clay bricks. Moatasem et al.38 concluded that the optimum strength of clay brick samples with sawdust is 3.3 N/mm2 with a mixing ratio of 15% sawdust and 85% clay. From Fig. 8, it can be seen that there is a negative effect of increasing the percentage of sawdust in the clay chips; as the amount of sawdust in the sample increases, its compressive strength decreases, and vice versa. This behavior is constant for the three test ages. It is also seen from this figure that the pure clay sample (without any additives) has the highest compressive strength for all test ages, followed by the sample with the mixing ratio (20% sawdust + 80% clay), and the lowest is the sample with the mixing ratio (40% sawdust + 60% clay).

Thermal behavior of test chips

The current work included verifying the effectiveness of three different types of thermal insulation materials for three models of design rooms (R1, R2, & R3) at the same operating conditions. The numerical solution assumed that the design conditions in the winter of Kirkuk City/Iraq included the inside temperature of the conditioned space (test rooms) being 25 °C and the ambient air temperature being −2 °C. Figure 9 shows that the use of thermal insulation (sawdust + clay) for R2 was close in terms of resistance to the transfer of heat to traditional thermal insulation materials such as Styrofoam, which in turn plays an effective role in saving power consumption inside the conditioned space. It is clear from Fig. 10 that the use of the proposed thermal material (sawdust + clay) has significantly contributed to reducing power consumption under different weather conditions by reducing the heat energy loss across the test wall. Also, in the numerical solution, the rate of thermal energy transmitted through a southern wall of the design rooms was calculated, considering that the heat loss through the other constructional areas of the room, such as the other walls, ceiling, and floor, was small in comparison with the southern wall. The amount of heat loss because of infiltration of the air through the cracks and installation holes around the doors and windows was not taken into consideration due to the lack of doors and windows in the design room.

To simulate the process of heating in buildings in the experimental part, therefore, was conducted during January 2021, which is considered one of the coldest months of the year in Iraq, where temperatures range between −2 and 15 °C. The study included two stages:

In the first stage, a preliminary test was conducted on the proposed design of a room without adding a thermal insulation material on the southern wall (a wall of pure aluminum sheet) to evaluate the performance and the possibility of modification in the proposed design. The second stage included studying the thermal behavior and the amount of energy consumed by the three test rooms under the same operating conditions.

The tests were conducted in varying climatic conditions (cloudy on 02 January 2021, rainy on 10 January 2021, and sunny on 19 January 2021), and the number of tests was 16. The hourly data were recorded for each parameter (such as electric current, energy consumed, the temperature inside the test room, ambient air temperature, and the temperatures of the inner and outside surfaces of the test wall). All experiments began at 9:00 am and continued for several hours and several days to determine the ability of each thermal insulation material to store or lose thermal energy, as well as the ability to withstand all different weather conditions.

To estimate the average energy consumption, the heat lamp was turned on continuously inside each test room (from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm). Figure 11 shows the hourly change of the ambient air temperature and the temperature of the inside test rooms (R1, R2, R3) for three different typical days (A) cloudy (02 January), (B) rainy (10 January), and (C) sunny (19 January of 2021), respectively. Looking at Fig. 11, it is clear that the lowest level of the internal temperature was recorded for the test R3 (sawdust + glue), which was recorded for the test R3 (sawdust + glue), which was recorded for the cloudy day at about 5.95 °C in the morning, 23.25 °C in the afternoon, and 21.24 °C in the evening; for the rainy day, about 6.55 °C in the morning, 25.58 °C in the afternoons, and 23.36 °C in the evening; as for the sunny test day, it was recorded about 7.14 °C in the morning, 27.90 °C in the afternoon, and 25.49 °C in the evening. The highest level of inside temperature was recorded in the R1 (Styrofoam), and it was recorded for the cloudy day at about 7.30 °C in the morning, 34.9 °C in the afternoon, and 31.4 °C in the evening. For the rainy day, it was about 8.03 °C in the morning, 38.39 °C in the afternoon, and 34.54 °C in the evening; as for the sunny test day, it recorded 8.76 °C in the morning, 41.88 °C in the afternoon, and 37.68 °C in the evening. As for the test R2, the internal temperatures for the cloudy day ranged between 6.57 °C in the morning, 27.87 °C in the afternoon, and 25.15 °C in the evening; for the rainy day, between 7.22 °C in the morning, 30.65 °C in the afternoon, and 27.66 °C in the evening; and for the sunny test day, it was recorded about 7.88 °C in the morning, 33.44 °C in the afternoon, and 30.18 °C in the evening.

Thus, if the control circuit of the heat is turned on from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm and set at a temperature of 25 °C (the comfort conditions in an air-conditioned space), therefore, the rate of operation of the heat source (heat lamp) and the average electrical energy consumed inside the three test rooms (R1, R2, and R3) for the cloudy, rainy, and sunny test days as shown in Table 4. From this table, it can be seen that the insulation material in R2 showed good compatibility with the traditional insulation material in R1, in terms of thermal insulation in various environmental conditions.

In the case of turning off the heat source control circuit, the average electrical power consumed inside the three test rooms (R1, R2, and R3) for the cloudy, rainy, and sunny days recorded the same behavior in the case of turning on the control circuit, as shown in Fig. 12. It is clear from this figure that the thermal insulation material in the second test room gave good compatibility in terms of power consumption over 9 continuous working hours (9:00 am-5:00 pm). Also, it was observed that the material (sawdust + clay) maintained its low value of thermal conductivity after being exposed to different climatic conditions (sunny, cloudy, rainy) for about 22 days, which reached about 0.62 W/m K, while a clear change was observed in the value of the thermal conductivity of the material (sawdust wood + glue), which reached about 3.64 W/m K. Whereas, the thermal conductivity value of traditional cork (Styrofoam) has not changed despite its exposure to varying climatic changes.

Conclusion and future research directions

The current study effectively examined the thermal insulation potential of sawdust-based materials, specifically sawdust-clay and sawdust-glue composites, as sustainable insulation solutions for buildings in hot-arid climates. Laboratory and real-world tests revealed that sawdust-clay insulation (20% sawdust and 80% clay) achieved a significantly lower thermal conductivity of 0.44 W/m K and maintained its insulation capacity over 22 days, rivaling traditional Styrofoam and reducing energy consumption in test rooms by up to 37%. This research highlights the importance of sawdust-based insulation in sustainable construction, particularly in areas with high cooling energy demands. By utilizing sawdust, a by-product of the wood industry that often contributes to environmental pollution when disposed of improperly, the study addresses waste management issues while promoting energy conservation. The sawdust-clay composite’s low thermal conductivity, structural stability, and cost-effectiveness make it a viable alternative to conventional insulation materials, especially for low-cost housing in regions with limited access to expensive options. The comparative testing of sawdust-clay and sawdust-glue composites revealed significant differences in performance and durability. The sawdust-glue composite (80% sawdust and 20% glue) exhibited reasonable thermal conductivity initially but deteriorated over time, with a 63% increase in conductivity after exposure to temperature fluctuations. This indicates that while glue-based binders may be suitable for certain applications, clay offers greater resilience, making it more suitable for insulating materials in extreme weather conditions. These findings can inform material selection for developers, particularly in hot climates like Iraq, where effective insulation can lead to substantial energy and cost savings. With air conditioning consuming up to 70–80% of total energy in such regions, effective insulation like sawdust-clay can significantly reduce cooling demands, lower utility bills, and minimize carbon footprints. Future research should focus on the long-term durability of sawdust-based composites under varying conditions, explore alternative natural binders for improved environmental compatibility, and assess moisture and fire resistance with specific additives. Additionally, economic analyses on the scalability and lifecycle costs of sawdust insulation could evaluate its financial viability compared to conventional materials, while testing in diverse climates could determine the broader applicability of the observed energy-saving benefits.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

16 September 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Naseer T. Alwan was incorrectly affiliated with ‘Nuclear Power Plants and Renewable Energy Sources Department, Ural Federal University, Yekaterinburg, 620002, Russia’. The correct affiliation is listed here: Department of Renewable Energy Techniques Engineering, College of Oil and Gas Techniques Engineering/Kirkuk, Northern Technical University, Kirkuk, Iraq.

References

Al-mudhafar, A. H. N., Hamzah, M. T. & Tarish, A. L. Potential of integrating PCMs in residential building envelope to reduce cooling energy consumption. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 27, 101360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2021.101360 (2021).

Alwan, N. T., Shcheklein, S. E. E. & Ali, O. M. Case studies in thermal engineering experimental investigation of modified solar still integrated with solar collector. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 19, 100614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2020.100614 (2020).

Alwan, N. T., Shcheklein, S. E. & Ali, O. M. Experimental investigation of solar distillation system integrated with photoelectric diffusion-absorption refrigerator (DAR), vol. 2290, p. 50023 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0027426

Alwan, N. T., Shcheklein, S. E. & Ali, O. M. Productivity of enhanced solar still under various environmental conditions in Yekaterinburg city/Russia. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 791, 1 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/791/1/012052

Alwan, N. T., Shcheklein, S. E. & Ali, O. M. Experimental investigations of single-slope solar still integrated with a hollow rotating cylinder. IOP Conference Series in Material Science Engineering, vol. 745, no. 1 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/745/1/012063

Cengel, Y. A. Thermodynamics : An Engineering Approach Introduction and Basic Concepts, vol. 8th, pp. 1–59 (2015).

Aditya, L. et al. A review on insulation materials for energy conservation in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 73, 1352–1365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.02.034 (2017).

N. Alharbawee, Investigation of thermal behaviour for various exterior walls materials and their impact on rationalization of energy consumption of Kirkuk city, Iraq, vol. 162, p. 05026 (2018).

Alwan, N. T. et al. Enhancement of the evaporation and condensation processes of a solar still with an ultrasound cotton tent and a thermoelectric cooling chamber. Electronics 11(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11020284 (2022).

Simona, P. L., Spiru, P. & Ion, I. V. Increasing the energy efficiency of buildings by thermal insulation. Energy Proc. 128, 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.09.044 (2017).

Yaqoob, S. J. et al. Efficient flatness based energy management strategy for hybrid supercapacitor/lithium-ion battery power system. IEEE Access 10, 132153–132163. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3230333 (2022).

Jwad, W. & Tarish, A. Autonomous control of multi-speed split unit air conditioning for space load response (2022). https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.7-9-2021.2314936

Lateef Tarish, A., Talib Hamzah, M. & Assad Jwad, W. Thermal and exergy analysis of optimal performance and refrigerant for an air conditioner split unit under different Iraq climatic conditions. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 19, 100595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsep.2020.100595 (2020).

Mehrez, I., Hachem, H. & Jemni, A. Thermal insulation potential of wood-cereal straws/plaster composite. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01353 (2022).

Gopinath, K., Anuratha, K., Harisundar, R. & Saravanan, M. Utilization of saw dust in cement mortar & cement concrete. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 6, 2015 (2015).

Ogundipe, O. M. & Jimoh, Y. A. Strength-based appropriateness of sawdust concrete for rigid pavement. Adv. Mater. Res. 367, 13–18 (2012).

Adu, S. et al. Maximizing wood residue utilization and reducing its production rate to combat climate change. Int. J. Plant For. Sci. 1(2), 1–12 (2014).

Clarke Jeanetter, “52 1 3,” p. 1–56 (2018).

Claudiu, A. Use of sawdust in the composition of plaster mortars. ProEnvironment 7, 30–34 (2014).

Tarish, A. L., Khalifa, A. H. N. & Hamad, A. J. Impact of the adsorbent materials and adsorber bed design on performance of the adsorption thermophysical battery: Experimental study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 31, 101808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2022.101808 (2022).

Mamza, P. A. P., Ezeh, E. C., Gimba, E. C. & Arthur, D. E. Comparative study of phenol formaldehyde and urea formaldehyde particleboards from wood waste for sustainable environment. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 3(9), 53–61 (2014).

Hurmekoski, E. How Can Wood Construction Reduce Environmental Degradation? 12 (European Forest Institute, 2017).

Kumar, D., Singh, S., Kumar, N. & Gupta, A. Low cost construction material for concrete as sawdust. Glob. J. Res. Eng. E Civ. Struct. Eng. 14(4), 1–5 (2014).

Asdrubali, F., D’Alessandro, F. & Schiavoni, S. A review of unconventional sustainable building insulation materials. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 4(2015), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2015.05.002 (2015).

Meyer, C. Concrete and Sustainable Development 501–512 (American Concrete Institute, ACI Special Publication, 2002). https://doi.org/10.14359/325.

Huseien, G. F. et al. Mechanical, thermal and durable performance of wastes sawdust as coarse aggregate replacement in conventional concrete. J. Teknol. 81(1), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.11113/jt.v81.12774 (2019).

Ding, C. et al. Research on fire resistance of silica fume insulation mortar. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 25, 1273–1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.06.004 (2023).

Ding, C., Xue, K. & Yi, G. Research on fire resistance and economy of basalt fiber insulation mortar. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44591-9 (2023).

Alabduljabbar, H. et al. Engineering properties of waste sawdust-based lightweight alkali-activated concrete: Experimental assessment and numerical prediction. Materials 13(23), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13235490 (2020).

Ibrahim, J. E. F. M., Tihtih, M. & Gömze, L. A. Environmentally-friendly ceramic bricks made from zeolite-poor rock and sawdust. Constr. Build. Mater. 297, 123715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123715 (2021).

Aigbomian, E. P. & Fan, M. Development of wood-crete building materials from sawdust and waste paper. Constr. Build. Mater. 40, 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.11.018 (2013).

Walker, R. & Pavía, S. Thermal performance of a selection of insulation materials suitable for historic buildings. Build. Environ. 94(P1), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.07.033 (2015).

Morales-Conde, M. J., Rodríguez-Liñán, C. & Pedreño-Rojas, M. A. Physical and mechanical properties of wood-gypsum composites from demolition material in rehabilitation works. Constr. Build. Mater. 114(2016), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.137 (2016).

Lacoste, C., El Hage, R., Bergeret, A., Corn, S. & Lacroix, P. Sodium alginate adhesives as binders in wood fibers/textile waste fibers biocomposites for building insulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 184, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.12.019 (2018).

Ahmed, W. et al. Effective use of sawdust for the production of eco-friendly and thermal-energy efficient normal weight and lightweight concretes with tailored fracture properties. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.009 (2018).

Cetiner, I. & Shea, A. D. Wood waste as an alternative thermal insulation for buildings. Energy Build. 168, 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.03.019 (2018).

Zou, S. et al. Experimental research on an innovative sawdust biomass-based insulation material for buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 260, 121029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121029 (2020).

Charai, M. et al. Thermal performance and characterization of a sawdust-clay composite material. Proc. Manuf. 46(2019), 690–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2020.03.098 (2020).

Kaharuddin, et al. Preptno peer rev preprint not peer ved. Cicc 11, 76–84 (2020).

Li, I. Y. A life cycle analysis and impact assessment on styrofoam collected through the reduction and recycling pilot program (2012).

Silvestre, J. D., Pargana, N., De Brito, J., Pinheiro, M. D. & Durão, V. Insulation cork boards-environmental life cycle assessment of an organic construction material. Materials 9, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9050394 (2016).

Olson, J. R. Thermal conductivity of some common cryostat materials between 0.05 and 2 K. Cryogenics (Guildf) 33(7), 729–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/0011-2275(93)90027-L (1993).

Mirsadeghi, M., Cóstola, D., Blocken, B. & Hensen, J. L. M. Review of external convective heat transfer coefficient models in building energy simulation programs: Implementation and uncertainty. Appl. Therm. Eng. 56(1–2), 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2013.03.003 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Naseer T. Alwan, Ali Lateef Tarish: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Salam J. Yaqoob: Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing. Mohit Bajaj, Ievgen Zaitsev: Project administration, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alwan, N.T., Tarish, A.L., Yaqoob, S.J. et al. Enhancing energy efficiency in buildings using sawdust-based insulation in hot arid climates. Sci Rep 15, 8349 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92924-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92924-7