Abstract

This study aimed to determine if 24-h movement behaviors (sedentary time, physical activity, and sleep), considered independently and together, were associated with declarative memory and hippocampal volume in late early childhood. Observational data were obtained from preschool-aged children (timepoint 1: n = 35 children, 3.9 ± 0.5 years; 6 months later: n = 28 children, 4.5 ± 0.5 years). Movement behaviors were measured with actigraphy. Outcomes were declarative memory and hippocampal subregion volumes. Multilevel models explored movement behaviors independently as absolute values, and with both absolute total activity, 24-h sleep duration, and night sleep efficiency. Movement behaviors were also explored as compositions in linear regression models. In independent models, sleep duration and moderate to vigorous physical activity were positively associated with total and right hippocampal volumes, respectively. When examined together, children meeting sleep recommendations were more likely to have larger total, right and left hemisphere, body, and tail hippocampal volumes. In our sample of preschool children, we observed positive associations between sleep duration and hippocampal volume, independent of age. To improve our understanding of the connections between 24-h behaviors and brain health in early childhood, larger samples that also consider the context and subcomponents of movement behaviors may be warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Declarative memory and hippocampal development in early childhood

Memory, or the ability to acquire new information and later recall it, is pivotal to learning and development in children as it serves as the foundation to gaining new knowledge and skills1. Declarative memory broadly includes the explicit ability to recall information about an event or experience (i.e., episodic memory) and retrieve general knowledge (i.e., semantic memory)2. These forms of memory contribute to overall cognitive functioning and are important for learning and language development in young children3,4. Memory performance depends on three primary processing components: (1) encoding (processing information that is taken up by working memory for longer-term storage), (2) consolidation/storage (the retention of information after encoding), and (3) retrieval (accessing previously learned information)3. The development of the episodic memory system relies on a brain network that encompasses the hippocampus and other regions, such as medial temporal cortices and neocortical structures4,5. The ability to recall visual and spatial information is strongly connected to declarative memory domains and the hippocampus2,6,7.

The hippocampus serves as a major contributor to memory4,5. Markers of the hippocampus that are connected to memory include both function (e.g., connectivity) and structure (e.g., volume)5,8,9,10,11,12. Anatomically, the hippocampus can be explored bilaterally (i.e., both hemispheres), by hemisphere, and also by subregions along the longitudinal axis (e.g., head, body, and tail)8. In both children and adults, memory improvements appear connected to the structural development and connectivity of the hippocampus9,10,11. This region is where memories are initially integrated in the short term, and it plays a significant role in the consolidation of memories5,7.

Both declarative memory and hippocampal structure undergo substantial development early in life (i.e., infancy through age 5 years). While memory improves markedly5, significant anatomical changes occur in the hippocampus throughout early childhood (i.e., under age 6)8,13,14. Whereas some brain regions experience rapid changes in the very early years, the hippocampus undergoes protracted development in that the maturity relating to synaptic connectivity is not reached until 5–7 years14. Between ages 4 and 8 years, total bilateral hippocampal volume follows a cubic growth trajectory, the hippocampal head increases volume in a quadratic growth pattern, and the volumes of the body and tail grow linearly8. Additionally, while the hippocampus has greater neural plasticity than other brain regions and appears adaptive to environmental factors throughout the lifespan, plasticity is the greatest during early childhood15. Development of the hippocampus and cognitive performance across childhood, such as memory, can be influenced by a range of environmental factors16,17, and there is growing evidence that children’s routines and behaviors of the 24-h cycle are potential correlates18,19,20.

Potential links between 24-h movement behavior, hippocampal volume, and memory

Over a day, children’s movement behaviors can be broadly classified as sedentary, physical activity, or sleep. These 24-h movement behaviors are formative during early childhood and are predictive of healthy activity levels and sleep in adolescence and adulthood21,22,23. Importantly, minimizing time spent sedentary, participating in adequate physical activity levels, and achieving sufficient sleep quantity and quality are beneficial to a range of physical health outcomes in children24,25. Furthermore, mounting evidence shows that 24-h movement behaviors are linked to mental and cognitive health in older children and adolescents19,26,27,28. Although sedentary behavior, physical activity, and sleep measures have been independently associated with memory and brain measures in older children and adults, less is known about early childhood. The preschool years may be sensitive to the interactive influences of physical activity and sleep on biological and psychosocial aspects of the brain29.

Associations between sleep, the hippocampus, and memory

Sleep appears to be an important influence on functions relating to the hippocampus and the consolidation of memories. Although associations between sleep metrics and hippocampal structure in school-age children and adolescents have been mixed30,31,32,33,34,35, literature in early childhood is limited20. However, a recent study by Riggins and Spencer36 reported a positive association between habitual sleep duration and hippocampal head subfield volume (CA2-4/DG) in 4- to 6-year-old children that was not present in 6- to 8-year-old children. There is considerable evidence that sleep benefits cognitive functions such as visuospatial memory encoding and consolidation in early childhood7,18,37. For example, during slow-wave sleep, as memories are replayed in the hippocampus, a combination of hippocampal and physiological sleep activity helps stabilize memories7.

Associations between physical activity and the hippocampus

In the aging brain, similar to sleep, physical activity appears to be an important agent of hippocampal plasticity. For example, hippocampal volume in adults may be increased (or more likely retained in the case of older adults) in response to exercise interventions38. In preadolescent children, positive39,40,41 and mixed42 associations have been reported in observational studies between cardiorespiratory fitness (a performance indicator strongly linked to physical activity) and hippocampal volume or blood flow. However, relations have been inconsistent between physical activity and hippocampal measures in older children and adolescents43,44,45. Limited experimental research has been reported in youth and focused only on connectivity46. Overall, research regarding sedentary behavior or physical activity concerning the hippocampus in children is limited and, to our knowledge, has not been explored in early childhood. Given the sensitive periods for hippocampal development in this life phase, hippocampal plasticity and connectivity in younger children may be prone to the influences of movement behaviors.

Associations between physical activity and memory

In older adults, physical activity also appears to benefit declarative memory, including visuospatial performance47. Although studies reporting on this memory domain are limited in children, findings are promising19. A recent review of experimental studies in older children included four acute (single) bout studies and one (chronic) intervention study and reported generally favorable effects of physical activity on memory48. Additionally, a few intervention studies that explored physical activity integrated into preschool academic lessons demonstrated favorable effects on declarative memory performance (i.e., recall of recently learned academic subject-specific knowledge or foreign language words)49,50,51,52,53. However, overall, research exploring waking movement behaviors and declarative memory is limited54, has not considered sedentary behavior, and importantly, has not accounted for sleep duration or quality55. In addition to their influence on one another, given that they occur within a 24-h or daily cycle (and thus are co-dependent), 24-h movement behaviors could have interactive influences on cognitive performance.

The current study

Although there is evidence of co-development between declarative memory and hippocampal volume5, whether 24-h movement behaviors are associated with these two outcomes in early childhood is unknown. Exploring such potential influences would contribute to our understanding of the relations between 24-h movement behaviors and cognition and brain health in early childhood, which is necessary to inform comprehensive behavior promotion recommendations and interventions for early childhood. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine if 24-h movement behaviors, considered independently and together, were associated with declarative memory and hippocampal volume in early childhood (i.e., ages 4–5 years). For memory, we hypothesized that children who had more physical activity, less sedentary time, longer sleep duration, and greater sleep efficiency would have better immediate memory performance and less decrements in performance over recall periods. Given the variation in hippocampal volume over this age range, we did not have a priori hypotheses for the relations between hippocampal volume measures and 24-h movement behaviors. However, it was predicted that children’s overall 24-h time use compositions would be associated with memory measures and hippocampal volumes.

Methods

Study overview

Data for the current study stem from a longitudinal study aimed at exploring the development of nap effects on declarative memory and hippocampal development. All protocols were approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board (Federal-wide Assurance #: FWA00005856). This research adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the US National Commission of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research Belmont Report. Informed consent and parent permission were obtained from all parents or legal guardians, and all child participants provided verbal assent. For the current study, we used data from the first two times—timepoint 1 and timepoint 2 (data collected 6 months after timepoint 1). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed for this study (Supplemental File S1)56.

Participants

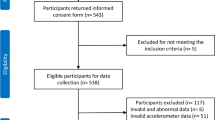

Children between the ages of 3 and 6 years who napped regularly (i.e., 5+ naps/week according to parent report) at the time of enrollment were eligible to participate in this study, as one of the aims of the parent study was to follow participants as they transitioned out of regular napping.

Additionally, inclusion criteria required children to have normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing, no current or past diagnosis of a developmental disability or sleep disorder, no use of psychotropic or sleep-affecting medications, be free of fever or respiratory illness at the time of testing, no history of neurological injury, and no presence of metal in the body. To be included in the present study, children needed sufficient actigraphy data (see Measures: “Actigraphy” section) and data for at least one outcome measure (i.e., memory or hippocampal volume) on one or more timepoints. Seventy-four children enrolled in the parent study, and among those, 43 had sufficient actigraphy measures (along with at least one memory or hippocampal measure; Fig. 1 and Supplemental File S2).

Protocol

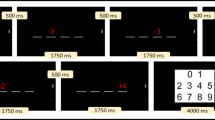

In the parent study, the study period at each timepoint was approximately 16 days and followed the same procedure (Fig. 2). Parents or adult caregivers were given online questionnaires and a sleep diary for their child. Children were given an actigraphy monitor and instructed to wear it on their non-dominant wrist and wear it continuously (i.e., 24-h) for the full study period. Each period included two experimental conditions that were implemented at the children’s homes 1 week apart with the order counterbalanced. The conditions included one afternoon of nap-promotion and one afternoon of wake promotion, regardless of the child’s typical daytime sleep routine. On these two experimental days, memory was assessed in the morning, the same afternoon (post-nap or post-wake), and 24 h later (i.e., in the morning). Approximately a week after the second condition was implemented, the child visited the campus for an MRI assessment57. In the current observational study, actigraphy from the two experimental days were excluded as the experimental conditions (i.e., nap-promotion or wake-promotion) may have created changes to a child’s typical routine.

Study overview. This simplified overview of the parent trial protocol was completed at two timepoints, 6 months apart. Notes: Analyses only included memory measures associated with the nap day promotion condition (i.e., immediate, same-day delayed, and next-day delayed recall). Actigraphy was measured throughout the full period, but only the ‘typical routine’ days were considered in the present study. Hippocampal volumes were obtained from the MRI visit.

Measures

Actigraphy

Daytime movement behaviors were derived from actigraphy. The current study used Actiwatch Plus monitors (Philips Respironics, Ben, OR), which employ triaxial accelerometry to estimate movement. These devices are water resistant, have off-wrist and light detection, and include an event marker button. This device is a prevalent measurement tool in pediatric sleep research58. Relative to video-polysomnography, one validity study in 28- to 73-month-old children reported overall agreement, sensitivity, and specificity metrics of 94%, 97%, and 24%, respectively59. In a study of preadolescent children, the validity of this device was examined as an estimate of daytime energy expenditure relative to indirect calorimetry (r = 0.90, p < 0.001)60. In preschool children, Alhassan et al.61 reported moderate positive associations comparing the activity counts output of the Actiwatch to direct observation (r = 0.47). Adult caregivers were asked to mark times that the monitor was taken off in the sleep diary. Children and adults were instructed to press the event button to mark lights on and off (to indicate time in and out of bed to determine bouts of sleep opportunity) for any sleep periods.

Actiwatch data was configured and downloaded in the Actiware software (Philips Respironics, Bend, OR). Devices were set with a sampling rate of 32 Hz, sensitivity < 0.01 g, and 15-s epochs for data collection. After data were downloaded, Actiware’s default algorithm was used to estimate sleep and wake intervals62. This algorithm has been validated in preschool samples58,63. This resulted in the categorization of each 15-s epoch as rest (awake in bed), sleep (sleep in bed), or wake (wake out of bed). Next, each rest interval was manually scored using a combination of information from Actiware (e.g., epoch classifications, light, event markers, and sleep diaries)64. Rest intervals were classified using the sleep diaries and event marker button presses. Sleep onset was defined as the first 3 consecutive minutes of sleep, and sleep offset was defined as the last 5 consecutive minutes of sleep if neither a diary nor event markers were available.

A valid daily cycle of actigraphy included at least 480 min of waking data and a full overnight of sleep data (i.e., no notable off-write intervals before or during the overnight period)65. Although the accelerometry review summary by Migueles et al.65 recommended a minimum of 600 min of wear time for activity assessment in this age group, the majority of our sample engaged in daytime naps at the first timepoint which reduced the number of hours available for waking activity counts. Percent of wake time spent in sedentary behavior and moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) were derived using the Ekblom intensity cut point ranges of ≤ 70 counts and > 262 counts, respectively60. At least two valid daily cycles of data were required for inclusion in the present analyses at each timepoint. To account for potential differences in wear periods between participants and weekends versus weekdays, for each timepoint, we used random effects models to estimate the individualized means for each actigraphy variable (i.e., total activity, sedentary time, light physical activity, MVPA, night sleep duration, 24-h sleep duration, and night sleep efficiency). A binary variable of meeting the AASM sleep duration recommendations for preschool children (i.e., 10 or more hours)66 was also created.

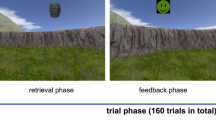

Memory

A visuospatial memory task used in previous work assessed declarative memory67. Research assistants administered this task via a computer or tablet in the participants’ homes on the days of the two conditions (nap and wake days). Given that daytime sleep can influence memory performance67, data for the present study was only used from the nap condition day. Similar to the game ‘Memory’, children were shown a grid of 12 or 16 cartoon images on a screen. For the encoding phase, children were asked to name each item, and then research assistants asked them questions about the items. The items were then ‘flipped over,’ and a grid of blue squares was presented in their place. Items were presented one at a time in a separate window and the children were asked to identify locations of the items with feedback provided. This phase continued until children reached 75% accuracy. Next, in the immediate recall phase, children were again asked to locate items on the same grid from earlier, but this time without feedback. Immediate recall accuracy (%) was calculated as the number of items correctly located divided by the number of items on the grid, multiplied by 100. After the participants woke from their afternoon nap, the same day delayed recall phase was administered following the same procedure as immediate recall. The difference between the delayed and immediate accuracy scores was divided by the immediate accuracy score and then multiplied by 100 to calculate the same delay percent change score. Finally, next day delayed recall also followed the same procedure as immediate recall, but was completed approximately 24 h post-encoding. The next day delayed recall score was computed using the same method as the same day delay, but with the next delay score in place of the same day delay score. Greater immediate recall scores (maximum possible score: 100%) indicated better memory performance. Greater change scores indicated more memory retention (or less forgetting) between the delayed recall assessments and immediate recall. Positive scores indicate that memory improved, whereas negative scores indicate performance decreased.

Hippocampal volume

During the MRI visit, children first participated in a mock scan to learn how to lie still in the scanner and get acclimated to the scanning environment. Motion feedback was provided by the research staff. Actual scans then followed the mock scan. Scanning was completed in a Siemens 3.0 T scanner with a 32-channel coil. To enhance compliance and reduce motion effects, padding was placed around the children’s heads and children watched a movie of their choice. A high-resolution T1 magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence of 176 contiguous sagittal slices was used to collect data (4:26 min acquisition time, 0.9 mm isotropic voxel size; 1900 ms TR; 2.32 ms TE; 900 ms inversion time; 9 flip angle; 256 × 256 pixel matrix). Following the scan, research staff checked images immediately and if the image was considered too low in quality (e.g., significant blurring or banding), a second scan was administered.

Structural data analysis was completed using Freesurfer (Version 6.0.0), a standard automatic segmentation program that has been deemed appropriate for use in children 4 and older68. Freesurfer provides automated preprocessing of structural T1-weight images, which involves skull stripping, image registration, motion correction, smoothing, and subcortical segmentation. To visually review the hippocampal segmentations, images were aligned to the anterior–posterior commissure. For slices selected as the end of the hippocampal head and the beginning of the hippocampal tail in both the left and right hemispheres, 13 cases were double-coded, and there was 100% agreement within two slices between raters. Quality inspections of the images resulted in exclusion if significant banding or blurring was present.

After the hippocampus was identified from Freesurfer, the segmentations were refined with the Automatic Segmentation Adapter Tool (ASAT: nitrc.org/projects/segadapter)69. During this process, each hemisphere was inspected for accuracy visually and if necessary, manual edits were made. Subsequently, using anatomical landmarks, hippocampal subregions were identified. Specifically, the end of the hippocampal head was marked as the slice before the uncal apex was visible, and then the head was identified as all slices prior to that slice70. The first slice where the fornix separated from the hippocampus (and became visible) was identified as the first slice of the tail71. All slices between the head and tail defined the hippocampal body. Finally, after the hippocampus was refined by ASAT, it was segmented (i.e., head, body, and tail) with the identified slice boundaries, and then volumes were extracted from Freesurfer. Freesurfer was also used to estimate and extract intracranial volume, total hippocampal volume, bilateral hippocampal volume (collapsed across hemisphere), and bilateral volumes for the head, body, and tail subregions. All hippocampal volumes were adjusted for intracranial volume for ICV using an analysis of covariance approach, taking into account both age and sex72,73 to ensure that differences in hippocampal volumes are not attributable to head size, age, or sex.

Covariates

Other measures were collected as potential covariates to include in our analyses and to describe the characteristics of the study sample. Caregivers completed an in-house health and demographics questionnaire. This included age (years and months), sex of the child, family income and education (as indicators of socioeconomic status), race, and ethnicity. For descriptive purposes, the number of days and nights of actigraphy data were recorded.

Analysis

Descriptive and preliminary analyses

Analyses were conducted in Stata (Version 17.0, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and in R version 4.2.274 using the compositions package75 with an alpha level of 0.05. Descriptive analyses were completed to characterize our sample and inform our models. Variables were first explored for normality and kurtosis. Next, pairwise Pearson correlations were run for all continuous variables to identify preliminary associations. Additionally, a series of independent t-tests were used to assess for differences in our variables by sex.

Main analyses

Multilevel linear models with restricted information maximum likelihood (i.e., one model for each outcome) were conducted to examine associations between movement behaviors as independent variables expressed as absolute values (i.e., sedentary time, MVPA, 24-h sleep duration, or night sleep efficiency) and memory performance or hippocampal volume as the dependent variables. We used two-level random intercept models with individuals nested within timepoints. Given the exploratory nature of our research questions and the level of missing data across timepoints, independent variables were grand mean-centered and treated as time-varying (by timepoint), and models included only random intercepts. Models were adjusted for sex.

To account for activity levels and sleep in the same model, multilevel models were also run, including total physical activity expressed as average activity counts/min (to account for both sedentary time and physical activity while avoiding multicollinearity concerns), 24-h sleep duration (as the categorical guideline compliance variable), and night sleep efficiency as independent, time-varying variables, with the same dependent variables mentioned above. These models were also adjusted for sex.

To explore the 24-h movement behavior as time-use metrics within the same model, we employed a compositional data analysis approach utilized in other time-use epidemiology studies76,77. This method enables the examination of measures that are interdependent within the same model while alleviating concerns about multicollinearity, treating these behaviors as a composition (i.e., each representing a proportion of the daily cycle) by converting them into log-ratio coordinates78. A 24-h time-use composition was developed for each child, consisting of the minutes spent sedentary, in light physical activity, in moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and in sleep (including both daytime and overnight sleep). The geometric means of these behaviors were computed, and the proportions were then normalized to total 1440 min (i.e., 24 h)76,79. Subsequently, the four-component time-use composition was transformed into a set of three isometric log-ratio (ilr) coordinates79,80. These three ilr coordinates, along with sex, were incorporated into linear regression models as independent variables, with a separate model for each outcome. Since each model included four independent variables, to maximize the sample size for each outcome, we chose to pool the data into a cross-sectional sample. Data from the first time point were prioritized; however, if data were missing, measures from the second time point were utilized. To determine whether the composition (i.e., the three ilr coordinate variables collectively) was associated with each outcome, multiple regression parameters from the type III analysis of variances were analyzed81. If the time-use composition emerged as a significant predictor for any outcome, theoretical time-use reallocations would be explored to describe the estimated changes in the outcome should time be added to or removed from a behavior82.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participant characteristics at each timepoint are presented in Table 1. Of the participants included in the present study, the majority of children were White (63.8%) and non-Hispanic (75.6%), came from families that reported an annual household income of over $115,000 (77.0%), and had at least one parent with a post-graduate degree (66.7%). Only three participants had household incomes less than $35,000, and all children had at least one parent with a high school diploma or higher. The average age at the start of the study was 3.9 ± 0.5 years, and over half of the sample was female (60.0%).

Timepoint 1 sample

Along with actigraphy data, at the first timepoint, 35 and 21 children had memory and hippocampal volume measures, respectively. Participants wore the Actiwatches for 2–16 daily cycles, with daytime wear time duration ranging from 662.0 to 813.4 min. This included 3.1 ± 1.4 weekends for daytime (i.e., daytime on Saturday and Sunday) and 2.9 ± 1.3 weekends for overnight sleep (i.e., Friday and Saturday nights). Over a daily cycle, children obtained 478.2–674.7 min of sleep duration, with 75% not meeting the AASM recommendations. For participants who napped, the average daytime sleep duration was 90.2 ± 19.0 min. Approximately one-third of the sample (n = 11) attended a childcare program or preschool outside of the home for 21.1 ± 17.6 h per week.

Timepoint 2 sample

At the second timepoint, along with actigraphy data, 28 children had actigraphy data, and 16 had hippocampal volumes. Demographic descriptions and actigraphy measures were similar to the first timepoint.

Cross-sectional sample

To create the pooled cross-sectional sample for our compositional data analyses, data was selected from the first timepoint if participants had data for all three variable categories (i.e., actigraphy, memory, and hippocampal volumes; n = 21). If a participant was missing data in one variable category but had all three at the following timepoint, their data was selected from the second timepoint (n = 8). If one category was missing at both timepoints, the first timepoint was given preference (n = 14). Descriptive statistics for this pooled sample (n = 43) were similar to those at both timepoints. The compositional means from the 24-h movement behavior composition were 328.6, 338.1, 128.8, and 644.4 min for sedentary time, light physical activity, MVPA, and sleep duration, respectively. A variation matrix computed with the geometric means indicated the lowest co-dependence between sedentary time and MVPA (0.200), and the highest co-dependence between light physical activity and sleep duration (0.014).

Initial analyses

Bivariate correlations between absolute values for sedentary time, MVPA, and sleep duration and the outcomes (i.e., memory and hippocampal measures) at the two timepoints were explored (Supplemental File S3). Total physical activity was negatively associated with age at timepoint 1 (r = − 0.37), indicating that older children (albeit within a small age range) were likely to be less active. Hippocampal body volume was inversely associated with MVPA at the first timepoint and inversely associated with 24-h sleep duration. There were no significant associations between 24-h behaviors and memory.

Next, we used independent t-tests to explore if variables of interest differed between males and females (Supplemental File S4). Males had 3.7% higher levels of MVPA (p = 0.03) and greater volume in the hippocampal head at both timepoints (p = 0.04). Females had better memory performance for immediate accuracy (9% higher, p = 0.043) and proportion of change between delayed and immediate recall on the same day (16.1% higher, p = 0.046). There were no sex differences in any of the measures at timepoint 2.

Main analyses

Individual behaviors as absolute variables

The first step in our main analyses used multilevel models to explore absolute values of sedentary time, MVPA, 24-h sleep duration, and night sleep efficiency in separate models adjusted for sex for each outcome of interest (Table 2).

None of the 24-h behaviors were associated with memory performance, although sex was a significant predictor in multiple models. Higher MVPA levels and greater 24-h sleep duration were associated with greater right and total hippocampal volumes, respectively. Specifically, each additional percent of wake time spent in MVPA was linked to an estimated increase in 4.1 mm3 in hippocampal head size, and each additional minute of sleep was associated with an estimated increase in 3.2 mm3 in total hippocampal size. Sex was significantly associated with hippocampal head volume in all 24-h behavior models.

Total activity, sleep guideline compliance, and night sleep efficiency together as absolute variables

Models were next explored for each outcome that included total physical activity (expressed as activity counts/min), 24-h sleep duration (expressed as a binary guideline compliance variable), night sleep efficiency, and sex as independent variables (Table 3). Children who met the sleep guidelines were more likely to have larger hippocampal volumes for the total hippocampus (β = 273.6, p < 0.001), left hemisphere (β = 139.9, p = 0.01), right hemisphere (β = 127.7, p < 0.001), head (β = 203.7, p = 0.006), and tail (β = 132.9 (p = 0.003). Sex was significantly associated with same-day memory recall performance and hippocampal head volume.

Compositional data analyses

Finally, a linear regression model for each model was explored that included the 24-h movement behavior composition expressed as three isometric-log ratios, night sleep efficiency, and sex as independent variables (Table 4). The 24-h composition was not a significant predictor for any of the outcomes, thus, these relations were not further explored with isotemporal time substitutions. Sex was significantly associated with immediate memory performance, same-day memory performance, and hippocampal head volume.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore relations between 24-h movement behaviors, both independently and interactively, on declarative memory and hippocampal volume in young children. Contrary to our expectations, the 24-h behaviors of the children in our sample were not associated with memory performance. When explored independently as an absolute value, MVPA was positively associated with the hippocampal volume of the right hemisphere, and sleep duration was positively associated with total hippocampal volume. After 24-h were combined as absolute values in the same model, sleep guideline compliance was associated with most hippocampal measures. Specifically, children who met the daily sleep recommendations were more likely to have greater hippocampal volumes for the total structure, left and right hemispheres, body, and tail than children who slept less than 10 h. When the time-use measures were treated as a composition, they were not significantly associated with any outcomes.

Similar to our non-significant associations, a prior study reported that hippocampal volume was not associated with actigraphy-measured absolute sedentary time in a sample of 93 preadolescent children who were classified as overweight or obese45. However, relations between sedentary behaviors and brain health measures may be a bit more nuanced than physical activity and fitness measures. Activities that may be categorized as sedentary, such as reading, writing, coloring/drawing, and even interactive gaming, could be beneficial for cognitive performance and development. Society’s increase in accessibility of technologies may contribute to increases in a child’s screen time. Yet some digital games and programming may also provide educational and developmental content, which may buffer against the negative effects of sedentary behavior. For example, sedentary time may negatively impact cognitive performance when it replaces sleep or physical activity, but the specific components of sedentary time (e.g., replacing reading or imaginative play for entertainment-related screen time) may also play a role. Thus, a consideration for future work would be to collect contextual information on the time spent in various types of sedentary behavior.

Contrary to the non-significant associations between absolute MVPA and total physical activity (that accounted for sleep duration) from this observational study, a few experimental studies in young children have demonstrated positive acute effects of MVPA on declarative memory performance49,50,51,52,53 and hippocampal connectivity83. In the cross-sectional study of 93 overweight or obese preadolescent children mentioned above, absolute MVPA was not associated with hippocampal volume in their overall sample45. However, when analyses stratified by weight classifications, MVPA was positively associated with the gray matter volume of the right hippocampus in children classified with type I obesity, but not in children classified as overweight or obesity class II–III, suggesting that weight status is an effect modifier.

Although this study allowed us to take a preliminary look at the relations of physical activity with memory and hippocampal volume, some aspects should be considered before extrapolating our findings. For example, our sample had generally high levels of physical activity, which may have contributed to a ceiling effect. Related to this, our measurement device and approach could have potentially overestimated MVPA. Specifically, although the wrist is the preferred wear location for sleep estimation in this age group, the hip or waist is generally more accepted and accurate for daytime activity levels45,84. Additionally, although the Ekbolm et al.60 cut points were cross-validated in our age group, they were originally developed in an older sample. Indeed, our compositional average was over 2 h of daily MVPA, which is higher than other preschool samples85. Additionally, in reports of youth studies exploring brain health measures, physical activity appears to have more mixed associations than cardiorespiratory fitness39,40,41,42. Lubans et al.29 have posited a conceptual model that proposes potential biological, psychosocial, and behavioral mechanisms linking physical activity to cognitive function. However, further research is needed, particularly in young children, to explore these potential pathways.

Although we did not observe independent relations for sleep duration and sleep efficiency in the initial separate models, some of the combined models exploring sleep as a categorical variable aligned with our exploratory hypotheses. Previous studies have reported a supporting role of various sleep biomarkers in both memory consolidation7,37 and hippocampal development20,36. It is possible that sleep duration itself, however, is not as meaningful as other sleep health measures. Although we used actigraphy-measured sleep efficiency as an indicator of sleep quality, there is some notable error associated with this metric when derived from actigraphy in children86. Other sleep quality variables, as measured through physiological markers via polysomnography, appear influential to memory consolidation. Such markers may include the proportion of time spent in slow-wave (or non-rapid eye movement stage 3 sleep), the number and density of sleep spindles, and the coupling of sleep spindles with slow-wave oscillations7,37.

Although there is less evidence regarding the relations of sleep metrics and hippocampal structure, a recent study also reported some associations between sleep duration and the hippocampus in 4- to 6-year-old children, specifically in the CA2-4 and dentate gyrus subfield of the hippocampal head36. Sleep disturbances may modulate some of the developmental processes that affect hippocampal structure (e.g., neural repair and reorganization), and thus, additional sleep quality measures may be important to consider in future work beyond sleep duration (e.g., sleep physiology or sleep fragmentation). The current study was unable to consider the link between other sleep health metrics and our outcomes.

It was important to consider all 24-h behaviors together because (1) in older samples, they have demonstrated independent effects and therefore could potentially act synergistically, and (2) one behavior may improve the other, which could have an indirect effect on our outcomes19,20. Although there have been some studies that used a compositional data analysis approach for other cognitive measures in early childhood, to our knowledge, only one study has explored declarative memory54 and none have included brain imaging measures. The current non-significant associations between the 24-h behavior composition and declarative memory replicate our recent finding in this age group54. In the study by Migueles et al.45, sedentary time and physical activity, when expressed as compositional components, were not associated with gray matter volume in the left or right hippocampi in the full sample of 93 preadolescents. However, sedentary time was negatively associated with gray matter volume in the right hippocampus in overweight children. Additionally, in children classified with type I obesity, MVPA was positively associated with gray matter volume in the right hippocampus. Future work should aim for larger sample sizes in this age group in order to incorporate a 24-h analysis approach while also controlling for additional covariates such as anthropometrics and explore potential effect modifications.

As indicated in the conceptual model by Lubans et al.29 factors such as sex, age, weight status, fitness level, and physical activity history may directly influence physical activity levels and, in turn, could indirectly relate or affect measures of brain health. Relatedly, although Migueles et al.45 did not observe significant associations in their full sample of children, weight status appeared to moderate the relations between movement behaviors and hippocampal volume in their study. Previous reports have noted the presence of sex differences for physical activity and hippocampal volume as early as the preschool years8,87. Unsurprisingly, such differences were present between variables of interest in our sample, and sex was a significant predictor in many of the models. However, due to the small sample size, we were unable to stratify our models on sex or assess for effect modification by including an interaction term. As such, we cannot rule out that relations between 24-h movement behaviors and the outcome measures may differ between males and females. Exploring potential effect modifiers in future research may be warranted.

In addition to some of the considerations already noted, this study has some limitations that should be noted. The sample size was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the expected loss to follow-up challenges generally associated with longitudinal designs. Additionally, for the current study, we were limited to participants with actigraphy measures, but the wear compliance may be related to its treatment as a secondary measure in the parent study. Relatedly, although socioeconomic status can influence both 24-h behaviors and brain structure17,88, we did not include this potential confounder in our models due to sample size. We included two participants who only had two nights of actigraphy data, although a minimum of 72 h and a combination of weekend and weekend sleep is typically recommended to estimate habitual patterns58. Although exploring hippocampal subfields (e.g., CA2, dentate gyrus) would be warranted, the resolutions of the MRI scans only allowed us to look at subregions. While physical activity was broken down into components based on intensity, our analyses were unable to consider the contexts of both sedentary time and sleep. In our compositional models, time in bed was used for the sleep component, which is often not equivalent to sleep duration (actual time asleep)89. As previously noted, despite potential misclassification or measurement error related to the activity monitors and placement, our sample was also relatively healthy, which may limit generalizability. The measures within our sample may not be representative of a general population, given the generally high parental income and educational levels. Additionally, while speculative, it is possible that given the socioeconomic status and health of the current sample, these children may have less screen time relative to the general population as well.

Conclusion

Overall, in our sample of 4- to 5-year-old children, sedentary time and physical activity were not associated with visuospatial declarative memory performance or hippocampal volume measures. Meeting age-specific sleep recommendations was associated with greater hippocampal volume in most of the included subregions. To improve our understanding of the potential connections between 24-h behaviors and brain health in early childhood, additional research is recommended that builds upon our approach. Specifically, we recommend exploring relations in larger samples that are diverse in both health and socioeconomic factors, exploring the role of cardiorespiratory fitness in this age group, and considering context and subcomponents of movement behaviors.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

McClelland, J. L., McNaughton, B. L. & Lampinen, A. K. Integration of new information in memory: New insights from a complementary learning systems perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 375(1799), 20190637 (2020).

Bouyeure, A. & Noulhiane, M. Memory: Normative development of memory systems. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 201–213 (Elsevier, 2020).

Harvey, P. D. Domains of cognition and their assessment. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 21(3), 227–237 (2019).

Ofen, N. et al. Development of the declarative memory system in the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 10(9), 1198–1205 (2007).

Riggins, T. & Bauer, P. J. A developmental neuroscience approach to the study of memory. In The Development of Memory in Infancy and Childhood (eds Courage, M. L. & Cowan, N.) (Psychology Press, 2022).

Roediger, H. L., Zaromb, F. M. & Lin, W. A typology of memory terms. In The Curated Reference Collection in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology, 7–19 (Elsevier Science Ltd., 2016).

Spencer, R. M. C. Neurophysiological basis of sleep’s function on memory and cognition. ISRN Physiol. 71(2), 233–236 (2013).

Canada, K. L., Botdorf, M. & Riggins, T. Longitudinal development of hippocampal subregions from early- to mid-childhood. Hippocampus 30, 1–14 (2020).

Ghetti, S. & Bunge, S. A. Neural changes underlying the development of episodic memory during middle childhood. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2, 381–395 (2012).

Spaniol, J. et al. Event-related fMRI studies of episodic encoding and retrieval: Meta-analyses using activation likelihood estimation. Neuropsychologia 47, 1765–1779 (2009).

Ostby, Y., Tamnes, C. K., Fjell, A. M. & Walhovd, K. B. Dissociating memory processes in the developing brain: The role of hippocampal volume and cortical thickness in recall after minutes versus days. Cereb. Cortex 22(2), 381–390 (2012).

Geng, F., Botdorf, M. & Riggins, T. How behavior shapes the brain and the brain shapes behavior: Insights from memory development. J. Neurosci. 41(5), 981–990 (2021).

Lavenex, P. & Banta Lavenex, P. Building hippocampal circuits to learn and remember: Insights into the development of human memory. Behav. Brain Res. 254, 8–21 (2013).

Brown, T. T. & Jernigan, T. L. Brain development during the preschool years. Neuropsychol. Rev. 22(4), 313–333 (2012).

Tottenham, N. & Sheridan, M. A. A review of adversity, the amygdala and the hippocampus: A consideration of developmental timing. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 3, 1019 (2010).

Lenroot, R. K. & Giedd, J. N. Brain development in children and adolescents: Insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 30(6), 718–729 (2006).

Brito, N. H. & Noble, K. G. Socioeconomic status and structural brain development. Front. Neurosci. 8, 276 (2014).

Mason, G. M., Lokhandwala, S., Riggins, T. & Spencer, R. M. C. Sleep and human cognitive development. Sleep Med. Rev. 57, 101472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101472 (2021).

Erickson, K. I. et al. Physical activity, cognition, and brain outcomes: A review of the 2018 physical activity guidelines. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 51(6), 1242–1251 (2019).

Lokhandwala, S. & Spencer, R. M. C. Relations between sleep patterns early in life and brain development: A review. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 56, 101130 (2022).

Jones, R. A., Hinkley, T., Okely, A. D. & Salmon, J. Tracking physical activity and sedentary behavior in childhood: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 44(6), 651–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.001 (2013).

Dregan, A. & Armstrong, D. Adolescence sleep disturbances as predictors of adulthood sleep disturbances—A cohort study. J. Adolesc. Health 46(5), 482–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.197 (2010).

Telama, R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: A review. Obes. Facts 2(3), 187–195 (2009).

Piercy, K. L. et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 320(19), 2020–2028 (2018).

Chaput, J. et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6), S265-282 (2016).

Saunders, T. J. et al. Combinations of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: Relationships with health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(6), S283–S293 (2016).

Fairclough, S. J. et al. Cross-sectional associations between 24-hour activity behaviours and mental health indicators in children and adolescents: A compositional data analysis. J. Sports Sci. 39(14), 1602–1614. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1890351 (2021).

Dumuid, D. et al. Goldilocks days: Optimising children’s time use for health and well-being. J. Epidemiol. Community Health https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-216686 (2021).

Lubans, D. et al. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics 138(3), e20161642 (2016).

Cheng, W. et al. Sleep duration, brain structure, and psychiatric and cognitive problems in children. Mol. Psychiatry 26(8), 3992–4003 (2021).

Hansen, M. et al. Socioeconomic disparities in sleep duration are associated with cortical thickness in children. Brain Behav. 13(2), e2859 (2023).

Dutil, C. et al. Influence of sleep on developing brain functions and structures in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 42, 184–201 (2018).

Urrila, A. S. et al. Sleep habits, academic performance, and the adolescent brain structure. Sci. Rep. 7, 41678 (2017).

Kocevska, D. et al. The developmental course of sleep disturbances across childhood relates to brain morphology at age 7: The generation r study. Sleep 40(1), zsw022 (2017).

Taki, Y. et al. Sleep duration during weekdays affects hippocampal gray matter volume in healthy children. Neuroimage 60(1), 471–475 (2012).

Riggins, T. & Spencer, R. M. C. Habitual sleep is associated with both source memory and hippocampal subfield volume during early childhood. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72231-z (2020).

Wilhelm, I., Prehn-Kristensen, A. & Born, J. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation—What can be learnt from children?. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36(7), 1718–1728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.002 (2012).

Firth, J. et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on hippocampal volume in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage 2018(166), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.007 (2017).

Chaddock, L. et al. A neuroimaging investigation of the association between aerobic fitness, hippocampal volume, and memory performance in preadolescent children. Brain Res. 1358, 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.049 (2010).

Esteban-Cornejo, I. et al. A whole brain volumetric approach in overweight/obese children: Examining the association with different physical fitness components and academic performance. The ActiveBrains project. Neuroimage 159(8), 346–354 (2017).

Chaddock-Heyman, L. et al. Aerobic fitness is associated with greater hippocampal cerebral blood flow in children. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 20, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2016.07.001 (2016).

Ortega, F. B. et al. Physical fitness and shapes of subcortical brain structures in children. Br. J. Nutr. 122(s1), S49-58 (2019).

Herting, M. M., Keenan, M. F. & Nagel, B. J. Aerobic fitness linked to cortical brain development in adolescent males: Preliminary findings suggest a possible role of BDNF genotype. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10(6), 1–11 (2016).

Ruotsalainen, I. et al. Aerobic fitness, but not physical activity, is associated with grey matter volume in adolescents. Behav. Brain Res. 362(1), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2018.12.041 (2019).

Migueles, J. H. et al. Associations of objectively-assessed physical activity and sedentary time with hippocampal gray matter volume in children with overweight/obesity. J. Clin. Med. 9(4), 1080 (2020).

Valkenborghs, S. R. et al. The impact of physical activity on brain structure and function in youth: A systematic review. Pediatrics 144(4), e20184032 (2019).

Cassilhas, R. C., Tufik, S. & De Mello, M. T. Physical exercise, neuroplasticity, spatial learning and memory. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 975–983 (2016).

Gunnell, K. E. et al. Physical activity and brain structure, brain function, and cognition in children and youth: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2019(16), 105–127 (2018).

Mavilidi, M. F., Okely, A. D., Chandler, P. & Paas, F. Infusing physical activities into the classroom: Effects on preschool children’s geography learning. Mind Brain Educ. 10(4), 256–263 (2016).

Mavilidi, M. F., Okely, A., Chandler, P., Louise Domazet, S. & Paas, F. Immediate and delayed effects of integrating physical activity into preschool children’s learning of numeracy skills. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 166, 502–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.09.009 (2018).

Mavilidi, M. F., Okely, A. D., Chandler, P. & Paas, F. Effects of integrating physical activities into a science lesson on preschool children’s learning and enjoyment. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 31(3), 281–290 (2017).

Mavilidi, M. F., Okely, A. D., Chandler, P., Cliff, D. P. & Paas, F. Effects of integrated physical exercises and gestures on preschool children’s foreign language vocabulary learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 27(3), 413–426 (2015).

Toumpaniari, K., Loyens, S., Mavilidi, M. F. & Paas, F. Preschool children’s foreign language vocabulary learning by embodying words through physical activity and gesturing. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 27(3), 445–456 (2015).

St. Laurent, C. W. et al. Associations of activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviors with cognitive and social-emotional health in early childhood. J. Act. Sedent. Sleep Behav. 2(1), 7 (2023).

St. Laurent, C. W., Burkart, S., Andre, C. & Spencer, R. M. C. Physical activity, fitness, school readiness, and cognition in early childhood: A systematic review. J. Phys. Act. Health 18(8), 1004–1013 (2021).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 12(12), 1495–1499 (2014).

Allard, T., Lokhandwala, S., Spencer, R. & Riggins, T. Nap habituality, hippocampal volume and memory in early childhood. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. (2024). Under Review.

Meltzer, L. J., Montgomery-Downs, H. E., Insana, S. P. & Walsh, C. M. Use of actigraphy for assessment in pediatric sleep research. Sleep Med. Rev. 16, 463–475 (2012).

Sitnick, S. L., Goodlin-Jones, B. L. & Anders, T. F. The use of actigraphy to study sleep disorders in preschoolers: Some concerns about detection of nighttime awakenings. Sleep 31(3), 395–401 (2008).

Ekblom, O., Nyberg, G., Bak, E. E., Ekelund, U. & Marcus, C. Validity and comparability of a wrist-worn accelerometer in children. J. Phys. Act. Health 9(3), 389–393 (2012).

Alhassan, S. et al. Cross-validation of two accelerometers for assessment of physical activity and sedentary time in preschool children. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 29(2), 268–277 (2017).

Oakley, N. Validation with polysomnography of the sleepwach sleep/wake scoring algorithm used by the Actiwatch activity monitoring system. Bend, OR (1997).

Bélanger, M. È., Bernier, A., Paquet, J., Simard, V. & Carrier, J. Validating actigraphy as a measure of sleep for preschool children. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 9(7), 701–706 (2013).

Acebo, C. et al. Sleep/wake patterns derived from activity monitoring and maternal report for healthy 1- to 5-year-old children. Sleep 28(12), 1568–1577 (2005).

Migueles, J. H. et al. Accelerometer data collection and processing criteria to assess physical activity and other outcomes: A systematic review and practical considerations. Sports Med. 47(9), 1821–1845 (2017).

Paruthi, S. et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: A consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 12(6), 785–786 (2016).

Kurdziel, L., Duclos, K. & Spencer, R. M. C. Sleep spindles in midday naps enhance learning in preschool children. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110(43), 17267–17272 (2013).

Ghosh, S. S. et al. Evaluating the validity of volume-based and surface-based brain image registration for developmental cognitive neuroscience studies in children 4 to 11 years of age. Neuroimage 53(1), 85–93 (2010).

Wang, Y., Loparo, K., Kelly, M. & Kaplan, R. F. Evaluation of an automated singlechannel sleep staging algorithm. Nat. Sci. Sleep 7, 101–111 (2015).

Weiss, A. P., Dewitt, I., Goff, D., Ditman, T. & Heckers, S. Anterior and posterior hippocampal volumes in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 73(1), 103–112 (2005).

Watson, C. et al. Anatomic basis of amygdaloid and hippocampal volume measurement by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology 42(9), 1743 (1992).

Raz, N. et al. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: General trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cerebr. Cortex 15(11), 1676–1689 (2005).

Keresztes, A. et al. Hippocampal maturity promotes memory distinctiveness in childhood and adolescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114(34), 9212–9217 (2017).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017).

van den Boogaart, K. G. & Tolosana-Delgado, R. “Compositions”: A unified R package to analyze compositional data. Comput. Geosci. 34(4), 320–338 (2008).

Dumuid, D., Pediši, Ž & Antoni, J. Compositional data analysis in time-use epidemiology: What, why, how. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 2220 (2020).

Brown, D. M. Y. et al. A systematic review of research reporting practices in observational studies examining associations between 24-h movement behaviors and indicators of health using compositional data analysis. J. Act. Sedent. Sleep Behav. 3(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44167-024-00062-8 (2024).

Dumuid, D. et al. Compositional data analysis for physical activity, sedentary time and sleep research. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 27(12), 3726–3738. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280217710835 (2017).

Pawlowsky-Glahn, V., Egozcue, J. J. & Tolosana-Delgado, R. Modelling and Analysis of Compositional Data (Wiley, 2015). (Statistics in Practice). Available from: http://silk.library.umass.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat06087a&AN=umass.015236067&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Egozcue, J. J., Pawlowsky-Glahn, V., Mateu-Figueras, G. & Barceló-Vidal, C. Isometric logratio transformations for compositional data analysis 1. Math. Geol. 35, 279–300 (2003).

Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression 2nd edn. (SAGE Publications, 2011).

Dumuid, D. et al. The compositional isotemporal substitution model: A method for estimating changes in a health outcome for reallocation of time between sleep, physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 28(3), 846–857 (2019).

Chen, A. G., Zhu, L. N., Yan, J. & Yin, H. C. Neural basis of working memory enhancement after acute aerobic exercise: FMRI study of preadolescent children. Front. Psychol. 7(9), 1–9 (2016).

Trost, S. G., Mciver, K. L. & Pate, R. R. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 37(11 SUPPL.), 531–543 (2005).

Hnatiuk, J. A., Salmon, J., Hinkley, T., Okely, A. D. & Trost, S. A review of preschool children’s physical activity and sedentary time using objective measures. Am. J. Prev. Med. 47(4), 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.042 (2014).

Galland, B., Meredith-Jones, K., Terrill, P. & Taylor, R. Challenges and emerging technologies within the field of pediatric actigraphy. Front. Psychiatry 5(8), 1–5 (2014).

Telama, R. et al. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: A 21-year tracking study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 28(3), 267–273 (2005).

Kracht, C. L., Webster, E. K. & Staiano, A. E. Sociodemographic differences in young children meeting 24-hour movement guidelines. J. Phys. Act. Health 16(10), 908–915 (2019).

Mindell, J. A., Meltzer, L. J., Carskadon, M. A. & Chervin, R. D. Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: Findings from the 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Poll. Sleep Med. 10(7), 771–779 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The parent trial study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01 HD079518 to TR and R21 HD094758 to TR and RMCS) and National Science Foundation (Grant BCS 1749280 to TR and RMCS). CWS was supported by NIH F32 HD105384.

Disclaimer

This article was prepared while Dr. Allard was employed at the University of Maryland. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: CWS, TR, RMCS; Methodology: CWS, AP, TR, RMCS; Formal analysis: CWS, AP; Investigation. SL, TA, AJ, TR, RMCS; Resources: TR, RMCS; Data curation: CWS, SL, TA, AJ, TR, RMCS; Writing—original draft: CWS; Writing—review and editing: SL, TA, AJ, AP, TR, RMCS; Visualization—CWS; Supervision and project administration: TR, RMCS; Funding acquisition—CWS, TR, RMCS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article was prepared while Dr. Allard was employed at the University of Maryland. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States Government. Portions of these data were presented at the virtual biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development (March 2021) and at the annual meeting of the International Society of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity in Uppsala, Sweden (June 2023).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

St. Laurent, C.W., Lokhandwala, S., Allard, T. et al. Relations between 24-h movement behaviors, declarative memory, and hippocampal volume in early childhood. Sci Rep 15, 9205 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92932-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92932-7