Abstract

Prevention of fetal growth restriction/small for gestational age (FGR/SGA) is adequate if screening is accurate. Ultrasound and biomarkers can achieve this goal; however, both are often inaccessible. This study aimed to develop, validate, and deploy a prognostic prediction model for screening FGR/SGA using only medical history. From a nationwide health insurance database (n = 1,697,452), we retrospectively selected visits to 22,024 healthcare providers of primary, secondary, and tertiary care. This study used machine learning (including deep learning) to develop prediction models using 54 medical-history predictors. After evaluating model calibration, clinical utility, and explainability, we selected the best by discrimination ability. We also externally validated the models using geographical and temporal splits of ~ 20% of the selected visits. The models were also compared with those from previous studies, which were rigorously selected by a systematic review of Pubmed, Scopus, and Web of Science. We selected 169,746 subjects with 507,319 visits for predictive modeling from the database, which were 12-to-55-year-old female insurance holders who used the healthcare services. The best prediction model was a deep-insight visible neural network. It had an area under the receiver operating characteristics curve of 0.742 (95% confidence interval 0.734 to 0.750) and a sensitivity of 49.09% (95% confidence interval 47.60–50.58% using a threshold with 95% specificity). The model was competitive against the previous models of 30 eligible studies of 381 records, including those using either ultrasound or biomarker measurements. We deployed a web application to apply the model. Our model used only medical history to improve accessibility for FGR/SGA screening. However, future studies are warranted to evaluate if this model’s usage impacts patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fetal growth restriction (FGR) and small for gestational age (SGA) are two terms with similar outcomes on babies but have different measures1. These measurements are emerging to differ FGR as pathological SGA from physiological SGA2,3. The former is also the second leading cause of preventable perinatal deaths4. The prevention method depends on FGR predictions with a clinically acceptable predictive performance5. However, most settings lack accessibility to predictors in existing prediction models6. Furthermore, acquiring information of current predictors may add unnecessary costs.

A pregnancy with FGR likely results in delivering low-birth-weight infants7, an indirect cause of neonatal deaths8,9,10. Neonatal mortality rates varied from 20 to 30 deaths per 1000 live births worldwide in 201311. Low-birth-weight infants also need to spend time in a neonatal intensive care unit12. But, this requires high costs and is a limited resource in many countries13,14. Prevention of FGR may reduce neonatal mortality and associated costs15. Several preventive strategies were found to be effective for FGR16; yet, this intervention needs a screening method with a good predictive performance5.

Since a low-cost method such as symphysis fundal height was not recommended by a Cochrane review, mainly due to low sensitivity (~ 17%), there is a trend to employ either ultrasound or biomarker measurements for FGR screening17. Nonetheless, these methods are inaccessible in resource-limited settings17,18. Meanwhile, there was an association detected of FGR with a woman’s medical history19. Because a health insurance claim database abundantly records medical histories, this allows proactive screening for FGR, particularly in countries with universal health coverage20. Screening by medical history is also independent of the number of pregnancy consultations on which FGR detection depends (hazard ratio 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05 to 1.26)21. While medical history-based solution does not incorporate a serial evidence of related to the progress of pregnancy, the association between medical histories and FGR may help to predict this condition at the end of pregnancy. However, studies have yet to develop a screening method for FGR using only medical history.

Prognostic predictions of FGR using medical histories can be either a prediction model for use in resource-limited settings or a preliminary prediction model before ordering ultrasound and biomarker measurements. In the context of preliminary prediction, we need to predict FGR in general population to be useful, including subpopulations with both low and high risks of FGR. Prediction using only medical history in general population was possible by applying both statistical and computational machine learning, including deep learning22,23. However, predicting an outcome in general population introduces a class imbalance problem because the prevalence of FGR is lower than that of high-risk population. Meanwhile, class imbalance correction techniques led to miscalibration of prediction models without significant improvement in discrimination ability24. To deal with this technical issue, FGR and SGA could be predicted in aggregate to increase the positive-case proportion. Subsequently, a positive prediction from this preliminary stage would initiate diagnostic follow-up to confirm FGR and to differ it from SGA. Therefore, the model can be expected to increase FGR detection without adding cost, or even potentially reducing costs. In this study, we aimed to develop, validate, and deploy a prognostic prediction model for screening FGR/SGA using only medical history in nationwide insured women.

Results

Subject characteristics

We obtained the data for this study from a nationwide health insurance database in Indonesia (n = 1,697,452)25. From the database, we selected 12-to-55-year-old females (n = 169,746). Among the selected insurance holders, some of them never used healthcare services; thus, we only selected those who had visited (n = 507,319) primary, secondary, or tertiary care (Fig. 1). After removing subjects with no pregnancy and their visits, we split the selected data for internal (~ 80%) and external validation (~ 20%). There were no overlapped visits between the internal and external validation sets. We only used the former to develop the prediction models in this study, including association tests to select candidate predictors.

Subject selection by applying a retrospective design and data partitioning for internal and external validations. Some of 12-to-55-year-old female insurance holders never used healthcare services, as recorded in the database; hence, we only selected those who had ever visited healthcare providers. The set for association tests included censored outcomes. The summation of the internal and external validation numbers differs from the total because: (1) there were subject overlaps; (2) the numbers of subjects and visits in the censored internal validation are not shown; and (3) we excluded subjects with no pregnancy before data analysis. a, the first and second pregnancies of a subject within the database period, not parity; b, subjects per pregnancy episode; c, only subjects in the external random split overlapped with those in the internal validation sets; n, sample size; (?), number of censorings; (–), number of nonevents; (+), number of events.

To characterize subjects in the internal validation set (Table 1), we also included subjects with uncensored outcomes (n = 26,576). There were differences between subjects without and those with FGR/SGA based on multiple univariate analyses. These were in terms of subject characteristics, i.e.: (1) maternal age; (2) third vs. first categories of the insurance class; (3) single vs. married categories of the marital status; and (4) private company vs. central-government employee categories of the occupation segment of the householder. We also identified differences in terms of latent candidate predictors. Two of these variables were the risk of adverse pregnancy by maternal age and a low socioeconomic status. The former represented maternal age of either < 20 or > 25 years, while the latter represented either the third insurance class or unemployed householder (Table C7). Differences in the latent candidate predictors implied their associations with the outcome.

Predictor selection

To select latent candidate predictors in the prediction models, their associations with the outcome were verified by multivariate analyses using inverse probability weighting (see Table C8 for comparison to those verified by logistic regression). We adjusted associations using confounders (Table 2; Figs. B1-B9). Significant associations persisted after adjustment, in which the effect sizes only slightly changed.

As the model input, the selected features were extracted using Kaplan Meier estimators, as previously described23. Such feature extraction would change the feature values to the models across time, since the values also depended on the interval between the times of prediction and feature documentation. A feature was non-zero and positive if it has been documented before the prediction time; otherwise, it was treated as zero.

The best prediction model

We developed five models. First, we applied ridge regression (RR) using the selected predictors. For the second to fourth model, we used the principal components (PCs) of the selected predictors and applied: (1) elastic net regression (PC-ENR); (2) random forest (PC-RF); and (3) gradient boosting machine (PC-GBM). The last model used the selected predictors and applied deep-insight visible neural network (DI-VNN). The best model was selected using internal validation. First, only the well-calibrated models were evaluated. Subsequently, we selected the models with net benefits higher than those if we treated all predictions as either positive or negative. The models were also selected if the feature importance was plausible according to clinicians’ assessment on the models’ explainability. Eventually, we chose the best among the selected models if it had the best discrimination ability.

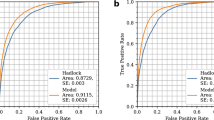

Only three of the five models were approximately well-calibrated (Fig. 2a): the PC-ENR, PC-GBM, and DI-VNN. Among these models, the PC-GBM was considerably the best-calibrated (intercept − 0.00098, 95% CI −0.13098 to 0.12902; slope 0.95, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.44; Brier score 0.0063). Nevertheless, the downstream analyses evaluated all of the well-calibrated models.

Model calibration(a), clinical utility(b), and discrimination by receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves (c). This figure shows only the well-calibrated models. We evaluated both using a calibration split (i.e., ~ 20% of internal validation set) within the optimal range of predicted probabilities (equivalent to thresholds) across all of the models (a). Solid lines with gray shading show the regression line and standard errors over point estimates of true probabilities (a). The threshold for each model is selected at ~ 95% specificity (b, c). The vertical dotted lines show 95% specificity (b, c), while the diagonal dotted lines show the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) of 0.5 as a reference (c). CI, confidence interval; DI-VNN, deep-insight visible neural network; ENR, elastic net regression; GBM, gradient boosting machine; PC, principal component.

The net benefits of these models were higher than those of either the treat-all or treat-none prediction (Fig. 2b). It also applied to those using a threshold of 95% specificity. With this threshold, we found the DI-VNN to be the best model in terms of clinical utility with a net benefit of 0.0023 (95% CI 0.0022 to 0.0024).

Regarding model explainability, both clinicians chose the DI-VNN among the well-calibrated models. They considered the plausibility of the top-five predictors according to the counterfactual probabilities (Table 3). One of the top predictors in the DI-VNN, i.e., severe preeclampsia, could change most of the predicted events into nonevents (probability of necessity [PN] of 98.57%, 95% CI 98.5–98.63%) if this predictor was changed from positive to negative. Some of the nonevents were also changed into events (probability of sufficiency [PS] of 2.08%, 95% CI 2.07–2.09%) if this predictor was changed from negative to positive. In addition, we also show the models’ parameters (Tables C9-C14) and all counterfactual probabilities (Tables C15-C17).

The discrimination ability differed among the well-calibrated models (Fig. 2c) according to the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves and area under the ROC curves (AUROCs). Based on the internal calibration split, we identified that the best model was also the DI-VNN (AUROC 0.742, 95% CI 0.734 to 0.750; sensitivity 49.09%, 95% CI 47.60–50.58%). Using external validation, the AUROC of the DI-VNN was considerably robust (Fig. 2c).

Systematic comparison to previous models

Furthermore, we compared the best model with those from previous studies. Only three studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria from three literature databases within the last 5 years. All of the studies were systematic reviews. Thus, we also searched eligible articles in the systematic reviews, including those published more than 5 years earlier. This step resulted in 381 records, including the three systematic reviews (Fig. B10). We included 27 studies (Tables D1, D2) of these records for the meta-analysis. These studies used only a training set; thus, the evaluation metrics were extracted only from the training set (Table C18).

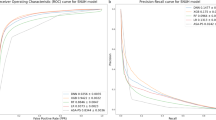

By estimation, the DI-VNN was only outperformed by five previous models from three of 27 studies (Fig. 3). The first model used ultrasound to measure pulsatility index (PI) of internal carotid artery (ICA-PI)26. The second model used PI of middle cerebral artery (MCA-PI)27. The third and fourth models used ICA-PI and MCA-PI with PIs of renal artery (RA-PI), and intra-abdominal aorta (AO-PI)26. However, those models were developed using smaller sample sizes (n≤162; Fig. 3 and Tables C18 and D2). The fifth model used MCA-PI with PI of uterine artery (UtA-PI) and umbilical artery (UA-PI), estimated fetal weight (EFW) by ultrasound, and two biomarkers, i.e., placental growth factor (PlGF) and soluble fms-like tyrosinase-1 (sFLT-1)28. This model was developed using sufficient sample size (n = 8268) but were only evaluated using training set (Fig. 3).

Comparison to previous models by the area under the receiver operating characteristics curves (AUROCs). Black rectangles indicate which predictors were used for each model. See Appendix D for details of eligible models from previous studies. ADAM12, A-disintegrin and metalloprotease-12; Alc., alcohol; AO, intra-abdominal aorta; βhCG, β-subunit human choriogonadotropin; BMI, body-mass index; Cig., cigarette; CRL, crown-rump length (fetus); CU-R, cerebral-umbilical ratio; DI-VNN, deep-insight visible neural network; EFW, estimated fetal weight; ENR, elastic net regression; Fam., family; GBM, gradient boosting machine; ICA, internal carotid artery; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MCA, middle cerebral artery; Med., medical; NT, nuchal translucency thickness (fetus); PAPP-A, pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A; PC, principal component; PlGF, placental growth factor; PI, pulsatility index; PP13, placental protein-13; RA, renal artery; RI, resistance index; ROC, receiver operating characteristics; SD, systolic-diastolic ratio; sFLT-1, soluble fms-like tyrosinase-1; UA, umbilical artery; UtA, uterine artery.

Meanwhile, based on the AUROC using external validation splits, the DI-VNN was also estimated to outperform four previous models, which used either ultrasound or biomarkers without or with other predictors. The first model used ultrasound to measure MCA-PI29. The second model used a biomarker and other predictors, i.e., pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) with maternal age, weight, race/ethnicity, and cigarette smoking status30. The third and fourth models used PAPP-A with ultrasound to measure crown-rump length (CRL) of fetus31,32. The three of four models30,31,32 were developed using sufficient sample size (n≥2760). However, all of the four models were only evaluated using training set.

Model deployment

Eventually, we chose the DI-VNN to predict FGR/SGA in advance among 12-to-15-year-old females that visited primary, secondary, or tertiary care. Similar to the development pipeline of the prediction model, only a pregnant woman was eligible for the use of the DI-VNN to compute a predicted probability of FGR/SGA. We deployed the DI-VNN as a web application (https://predme.app/fgr_sga/). It can be used for future use or independent validation of the DI-VNN because it is open access. Notably, since we extracted the features using the International Classification of Disease version 10 (ICD-10) codes of diagnoses and procedures, the use of our models in other countries must convert the codes to ICD-10 if they used other versions, e.g., ICD-9.

Discussion

We developed, validated, and deployed a web application to predict FGR/SGA in advance using the medical history of diagnoses and procedures. The prediction model for the web application was the DI-VNN, chosen among five prediction models in this study, using only an internal validation set. However, external validation also demonstrated the robustness of the DI-VNN’s predictive performance. It was also comparable to those developed in the previous studies, which used ultrasound and biomarkers without or with other predictors.

For predicting FGR/SGA, the previous models, as systematically reviewed in this study (Table D2), mainly required either ultrasound or biomarker measurements and a specific range of gestational ages. The models included those which were competitive with the DI-VNN based on the AUROC by internal validation (Fig. 3). The models were by Shlossman, Scisione26 (using ICA-PI, MCA-PI, and AO-PI), Bednarek, Dubiel27 (using MCA-PI), and Valiño, Giunta28 (using MCA-PI, UtA-PI, UA-PI, EFW, PlGF, and sFLT-1). Conversely, external validation estimated that the DI-VNN would outperform the other previous models with the similar requirements. The models were by Bano, Chaudhary29 (using MCA-PI), Carbone, Tuuli31 and Leung, Sahota32 (using PAPP-A and CRL), and Krantz, Goetzl30 (using PAPP-A and maternal age, weight, race/ethnicity, and cigarette smoking status). Furthermore, evaluation of the previous models used training sets only, in which the predictive performances might have been overoptimistic.

The DI-VNN required neither ultrasound nor biomarkers without or with other predictors. We would expect wider access for FGR/SGA predictions as either (1) a prediction model for use in resource-limited settings or (2) a preliminary prediction model before ordering advanced predictor measurements. The clinical applicability of our model is to increase accessibility to FGR prognostication by two strategies: (1) targeting general population with both low and high risk of FGR; and (2) extending the range of gestational ages. The first strategy enables the detection of ~ 50% pregnancies with FGR/SGA while only 5% of those without these conditions being ruled-out. The second strategy allows a follow-up for FGR diagnosis and its prevention in early pregnancy (e.g., < 16 week’s gestation) and an increased vigilance to mitigate bad outcomes of FGR (e.g., at 36 weeks’ gestation). While our model could not differ FGR from physiological SGA since we predicted FGR and SGA in aggregate due to technical consideration, we have achieved our expectation for this study, i.e., wider accessibility of FGR prognostication using only medical histories. However, the DI-VNN needs an impact study to evaluate its effect on patient outcomes in various settings.

Medical histories as the predictors in our model were measured by ICD-10 codes related to the health insurance claim. Our predictors might represent either FGR pathology or socioeconomic factors that drive or relate to FGR. For example, individuals with lower socioeconomic level might share similar incidence of both infectious diseases and FGR. Any of the infectious diseases might cause FGR or the common causes/risk factors with FGR. Regardless of what our predictors represent, this situation commonly applies to any clinical prediction models. Hence, our model can be used in other settings with different health insurance system or jurisdictions, e.g., other countries. The potential caveat for using our model lie on how diagnoses and procedures are coded. Some countries may use different ICD versions, such as ICD-9. The code conversion may introduce errors. Furthermore, healthcare givers in other countries may have different interpretation in coding the diagnoses and procedures. However, the best model in this study applied DI-VNN. One can fine-tune our DI-VNN model using smaller sample size by updating the feature map and ontology on top of those for our model in this study33. Therefore, we can expect the generalization of our model in other countries without re-training the model with a large sample size.

An effective prevention for FGR was given by ≤ 16 weeks’ gestation5. To widen prevention time window, more clinical trials are needed. These studies are more efficient if they are conducted among pregnant women with higher risk, as predicted by the DI-VNN. Since it did not require a specific range of gestational ages, the DI-VNN opens more opportunities to conduct such trials.

One of the strengths of this study were no requirements from our models, including the DI-VNN, for either ultrasound or biomarker measurements to predict FGR/SGA in advance. We could apply our models to a general population of pregnant women. Furthermore, our model did not require a specific gestational age range for computing the predicted probability. Unlike previous studies, we also conducted external validation to estimate the future predictive performance of the DI-VNN.

However, we also identified several limitations of this study. The predictive performance of the best model, i.e., the DI-VNN, was considerably moderate according to the AUROC as was the sensitivity at 95% specificity using an internal validation set. However, previous models also achieved similar predictive performances. Another limitation was that medical histories from electronic health records might take time to execute; yet, this is considerably more achievable in many settings. It still needs to be determined if the DI-VNN can improve patient outcomes. Nevertheless, this problem is not exclusive to this study because many previous studies in medicine have yet to evaluate the impacts of their prediction models34.

Methods

Report completeness of this study was according to the transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD) checklist (Appendix A)35. We followed a protocol with the same software and hardware (Tables B1-B3, C1)23, except those stated otherwise. This study was under a single project that compared a DI-VNN to other machine learning algorithms to predict several outcomes in medicine. The Taipei Medical University Joint Institutional Review Board exempted this project from the ethical review and the need for informed consent (TMU-JIRB no.: N202106025). We also confirm that all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study design and data source

We applied a retrospective design to select subjects from a public dataset version 2 (August 201925; access approval no.: 5064/I.2/0421) of a nationwide health insurance database in Indonesia. The dataset was a cross-sectional, random sampling of ~ 1% of insurance holders within 2 years up to 2016. This sampling included all affiliated healthcare providers (n = 22,024) at all levels (i.e., primary, secondary, and tertiary care).

The inclusion criteria were females aged 12 to 55 years who had visited primary, secondary, or tertiary care facilities. All visits afterward were excluded if a woman was pregnant and had a delivery. If a woman became pregnant twice within the dataset period, then different identifiers were assigned to differentiate the pregnancy periods of that woman. To determine a delivery, we used several codes of diagnoses and procedures (Table C2).

External validation was conducted using geographical and temporal splitting by ~ 20% of the selected visits (Fig. 1), as recommended by the PROBAST guidelines36. Instead of directly random-splitting of the visits, we randomly selected cities/regencies and time periods and included the visits from the subjects in these cities/regencies and time periods for external validation. The remaining visits were used for interval validation.

This study developed a prediction model for detecting in advance a visit by a subject who would be diagnosed with either FGR or SGA. We pursued to achieve an acceptable sensitivity at 95% specificity but using more-accessible predictors. Nevertheless, we compared our prediction models with those from previous studies selected by systematic review methods to evaluate if our predictive modeling was successful. Since there were different policies in choosing a prediction threshold (e.g., that at 90% vs. 95% specificity), the comparison was conducted using ROC curves and the AUROC.

Our prediction model was intended to be applied at any time point during pregnancy prior to pregnancy termination. The features of the model were selected from all available medical histories of diagnoses and procedures in the database up to the time of prediction. A feature was positive if it has been documented before the prediction time; otherwise, it was treated as negative (i.e., censored as negative). To deal with the censoring nature of the features, we employed Kaplan-Meier estimator for feature extraction, as describe in the previous protocol23. Using this estimator, the feature with positive value would have non-zero value, while that with negative value was zero. This approach enables the model for use at different gestational ages.

Outcome definition

The event outcome definition in this study utilized the ICD-10 codes. These were codes preceded by either O365 (maternal care for known or suspected fetal growth) or P05 (disorders of newborns related to slow fetal growth and fetal malnutrition). Both codes indicating FGR and SGA were assigned with those respectively for mothers and fetuses/newborns. A nonevent outcome was assigned if the end of pregnancy was identified within the dataset period by the codes for determining delivery. Otherwise, we assigned an outcome to a censored one.

Candidate predictors

Candidate predictors were only medical histories of diagnoses and procedures. These were either single or multiple ICD-10 codes. As extensively described in the protocol35, the preprocessing of candidate predictors consisted of (1) preventing zero variance, perfect separation and leakage of the outcome, and redundant predictors; (2) simulating real-world data; and (3) systematically determining the multiple ICD-10 codes for defining latent candidate predictors based on prior knowledge. After this preprocessing (Tables C3-C7), we identified 54 candidate predictors, including four latent candidate predictors of multiple pregnancies, varicella, urinary tract infections, and placenta previa.

Multivariable predictive modeling

We developed five models using different algorithms and hyperparameter tuning, as described in the protocol35. The first applied RR. The second to fourth models used 54 candidate predictors transformed into PCs. We applied three algorithms using these PCs: (1) PC-ENR; (2) PC-RF; and (3) PC-GBM. The fifth model was a DI-VNN. However, unlike the protocol35, we did not limit this model to only 22 of 54 candidate predictors, which had a false discovery rate of ≤ 5% based on differential analyses with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing corrections. Instead, we used all 54 candidate predictors considering the feasibility of constructing the data-driven network architecture. In addition, all model recalibration was by either a logistic regression or a general additive model using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. The recalibration procedure also differed from the protocol35. This is because the models only sometimes resulted in a wide range of predicted probabilities, as required for recalibration. Unlike the protocol, we chose 100 repetitions for bootstrapping, considering the sample size of this study compared to that of the protocol. Details on model development and validation are described in Table B2.

For deployment, this model will predict the outcome each time an insured woman visits a healthcare provider. We provided the best model in this study as a web application. A user is only required to upload a comma-separated value (.csv) file consisting a two-column table. It includes column headers of “admission_date” (yyyy-mm-dd) and “code” (ICD-10 code at discharge) from previous to current visits.

Statistical analysis

We computed an uncertainty interval (i.e., 95% confidence interval, CI) for each evaluation metric. This interval inference used subsets of an evaluated set, resampled by bootstrapping and cross-validation. All analytical codes were publicly shared (see “Data sharing statement”).

The selection of latent candidate predictors in the first model applied inverse probability weighting for the multivariate analyses, according to the protocol35. Results were also compared to those by outcome regression. We selected a latent candidate predictor if its association with the outcome had an interval of odds ratio excluding a value of 1.

The evaluation metrics were those for assessing the models’ calibration, utility, explainability, and discrimination. To evaluate the model calibration, we assessed (1) a calibration plot with a regression line and histograms of either event or nonevent distribution of the predicted probabilities; (2) the intercept and slope of the linear regression; and (3) the Brier score. We measured the clinical utility using a decision curve analysis by comparing the net benefits of a model with those if we treated all predictions as either positive (i.e., treat all) or negative (i.e., treat none). Clinicians (i.e., FZA and AZZAH) assessed the explainability. They were given counterfactual quantities for each predictor in a model37. These consisted of the PN (Eq. 1) and the PS (Eq. 2). Eventually, we evaluated the discrimination ability of well-calibrated models by the ROC curve and sensitivity at 95% specificity.

Furthermore, we compared our models with previous ones identified by a systematic review and meta-analysis. We compared the best model with those from previous studies. These were identified by following 11 of 14 items in section methods of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA)-extended checklist statements38. Those items are described in Table B4.

Data availability

The social security administrator provided the data for health or badan penyelenggara jaminan sosial (BPJS) kesehatan in Indonesia, with restrictions (access approval no.: 5064/I.2/0421). Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request (HS, herdi@nycu.edu.tw; ECYS, emilysu@nycu.edu.tw) and with permission of the BPJS Kesehatan. The latter needs a request to the BPJS Kesehatan for their sample dataset published in August 2019 via https://e-ppid.bpjs-kesehatan.go.id/. To visit this site, a visitor must use a device with an internet protocol (IP) address in Indonesia. Up to the publication of this study, the data access permission is only given to a research group of which the applicant person is an Indonesian citizen. The permission request and all other communications are made by registering an account in the website. The analytical codes are available at https://github.com/herdiantrisufriyana/fgr_sga.

Abbreviations

- AO:

-

Intra-abdominal aorta

- AUROC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristics curve

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DI-VNN:

-

Deep-insight visible neural network

- EFWL:

-

Estimated fetal weight

- ENR:

-

Elastic net regression

- FGR:

-

Fetal growth restriction

- GBM:

-

Gradient boosting machine

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Disease version 10

- MCA:

-

Middle cerebral artery

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PAPP-A:

-

Pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A

- PC:

-

Principal component

- PI:

-

Pulsatility index

- PlGF:

-

Placental growth factor

- PN:

-

Probability of necessity

- PS:

-

Probability of sufficiency

- RA:

-

Renal artery

- RF:

-

Random forest

- RI:

-

Resistance index

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristics

- RR:

-

Ridge regression

- sFLT-1:

-

Soluble fms-like tyrosinase-1

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- UA:

-

Umbilical artery

- UtA:

-

Uterine artery

References

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Fetal growth restriction: ACOG practice bulletin, number 227. Obstet. Gynecol. 137(2), e16–e28 (2021).

Gordijn, S. J. et al. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: a Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 48(3), 333–339 (2016).

Molina, L. C. G. et al. Validation of Delphi procedure consensus criteria for defining fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 56(1), 61–66 (2020).

Nardozza, L. M. et al. Fetal growth restriction: current knowledge. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 295(5), 1061–1077 (2017).

Roberge, S. et al. The role of aspirin dose on the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 216(2), 110–120e6 (2017).

Pedroso, M. A. et al. Uterine artery doppler in screening for preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 40(5), 287–293 (2018).

Mallia, T. et al. Genetic determinants of low birth weight. Minerva Ginecol. 69(6), 631–643 (2017).

Lawn, J. E., Cousens, S. & Zupan, J. 4 Million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet 365(9462), 891–900 (2005).

Ausbeck, E. B. et al. Neonatal outcomes at extreme prematurity by gestational age versus birth weight in a contemporary cohort. Am. J. Perinatol. 38(9), 880–888 (2021).

Tabet, M. et al. Smallness at birth and neonatal death: reexamining the current Indicator using sibling data. Am. J. Perinatol. 38(1), 76–81 (2021).

Lehtonen, L. et al. Early neonatal death: A challenge worldwide. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 22(3), 153–160 (2017).

Colella, M. et al. Neonatal and Long-Term consequences of fetal growth restriction. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 14(4), 212–218 (2018).

Umran, R. M. & Al-Jammali, A. Neonatal outcomes in a level II regional neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr. Int. 59(5), 557–563 (2017).

Horbar, J. D. et al. Racial segregation and inequality in the neonatal intensive care unit for very Low-Birth-Weight and very preterm infants. JAMA Pediatr. 173(5), 455–461 (2019).

Ho, T. et al. Improving value in neonatal intensive care. Clin. Perinatol. 44(3), 617–625 (2017).

Bettiol, A. et al. Pharmacological interventions for the prevention of fetal growth restriction: A systematic review and network Meta-Analysis. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 110(1), 189–199 (2021).

Audette, M. C. & Kingdom, J. C. Screening for fetal growth restriction and placental insufficiency. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 23(2), 119–125 (2018).

Luntsi, G. et al. Achieving universal access to obstetric ultrasound in resource constrained settings: A narrative review. Radiography (Lond). 27(2), 709–715 (2021).

Selvaratnam, R. J. et al. Risk factor assessment for fetal growth restriction, are we providing best care? Aust N Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 60(3), 470–473 (2020).

Wagstaff, A. & Neelsen, S. A comprehensive assessment of universal health coverage in 111 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 8(1), e39–e49 (2020).

Andreasen, L. A. et al. Why we succeed and fail in detecting fetal growth restriction: A population-based study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 100(5), 893–899 (2021).

Sufriyana, H., Wu, Y. W. & Su, E. C. Artificial intelligence-assisted prediction of preeclampsia: development and external validation of a nationwide health insurance dataset of the BPJS Kesehatan in Indonesia. EBioMedicine 54, 102710 (2020).

Sufriyana, H., Wu, Y. W. & Su, E. C. Y. Human and Machine Learning Pipelines for Responsible Clinical Prediction Using high-dimensional Data (Protocol Exchange, 2021).

van den Goorbergh, R. et al. The harm of class imbalance corrections for risk prediction models: illustration and simulation using logistic regression. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 29(9), 1525–1534 (2022).

Ariawan, I., Sartono, B. & Jaya, C. Sample Dataset of the BPJS Kesehatan 2015–2016 (Jakarta BPJS Kesehatan, 2019).

Shlossman, P. et al. Doppler assessment of the intrafetal vasculature in the identification of intrauterine growth retardation. Which vessel is ’best’ or is a combination better? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 178(S1), S88 (1998).

Bednarek, M., Dubiel, M. & Brêborowicz, G. H. P05.18: doppler velocimetry in M1 and M2 segments of middle cerebral artery in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 24(3), 300–301 (2004).

Valiño, N. et al. Biophysical and biochemical markers at 30–34 weeks’ gestation in the prediction of adverse perinatal outcome. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 47(2), 194–202 (2016).

Bano, S. et al. Color doppler evaluation of cerebral-umbilical pulsatility ratio and its usefulness in the diagnosis of intrauterine growth retardation and prediction of adverse perinatal outcome. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging. 20(1), 20–25 (2010).

Krantz, D. et al. Association of extreme first-trimester free human chorionic gonadotropin-beta, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, and nuchal translucency with intrauterine growth restriction and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 191(4), 1452–1458 (2004).

Carbone, J. F. et al. Efficiency of first-trimester growth restriction and low pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A in predicting small for gestational age at delivery. Prenat Diagn. 32(8), 724–729 (2012).

Leung, T. Y. et al. Prediction of birth weight by fetal crown-rump length and maternal serum levels of pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A in the first trimester. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 31(1), 10–14 (2008).

Sufriyana, H., Wu, Y. W. & Su, E. C. Human-guided deep learning with ante-hoc explainability by convolutional network from non-image data for pregnancy prognostication. Neural Netw. 162, 99–116 (2023).

Zhou, Q. et al. Clinical impact and quality of randomized controlled trials involving interventions evaluating artificial intelligence prediction tools: a systematic review. NPJ Digit. Med. 4(1), 154 (2021).

Moons, K. G. et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 162(1), W1–73 (2015).

Moons, K. G. M. et al. PROBAST: A tool to assess risk of Bias and applicability of prediction model studies: explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 170(1), W1–w33 (2019).

Moraffah, R. et al. Causal interpretability for machine learning-problems, methods and evaluation. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsl. 22(1), 18–33 (2020).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 372, n71 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The Badan Ppenyelenggara Jaminan Sosial (BPJS) Kesehatan in Indonesia permitted access to the sample dataset in this study. This study was funded by: (1) the Postdoctoral Accompanies Research Project from the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) of Taiwan (grant nos.: NSTC111-2811-E-038-003-MY2 and NSTC113-2811-E-A49A-003), and the Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat (LPPM) Universitas Nahdlatul Ulama Surabaya of Indonesia (grant no.: 161.4/UNUSA/Adm-LPPM/III/2021) to Herdiantri Sufriyana; and (2) the National Science and Technology Council in Taiwan (grant no. NSTC113-2221-E-A49-193-MY3), the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Taiwan (grant nos.: MOST110-2628-E-038-001 and MOST111-2628-E-038-001-MY2), the University System of Taipei Joint Research Program (grant no.: USTP-NTOU-TMU-112-04), and the Higher Education Sprout Project from the Ministry of Education (MOE) of Taiwan (grant no.: DP2-111-21121-01-A-05 and DP2-TMU-112-A-13) to Emily Chia-Yu Su. These funding bodies had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. FZA: Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. AZZAH: Validation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. YWW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing— Review & Editing, Supervision. ECYS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sufriyana, H., Amani, F.Z., Al Hajiri, A.Z. et al. Widely accessible prognostication using medical history for fetal growth restriction and small for gestational age in nationwide insured women. Sci Rep 15, 8340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92986-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92986-7