Abstract

Machine learning technology has been extensively applied in the medical field, particularly in the context of disease prediction and patient rehabilitation assessment. Acute spinal cord injury (ASCI) is a sudden trauma that frequently results in severe neurological deficits and a significant decline in quality of life. Early prediction of neurological recovery is crucial for the personalized treatment planning. While extensively explored in other medical fields, this study is the first to apply multiple machine learning methods and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) analysis specifically to ASCI for predicting neurological recovery. A total of 387 ASCI patients were included, with clinical, imaging, and laboratory data collected. Key features were selected using univariate analysis, Lasso regression, and other feature selection techniques, integrating clinical, radiomics, and laboratory data. A range of machine learning models, including XGBoost, Logistic Regression, KNN, SVM, Decision Tree, Random Forest, LightGBM, ExtraTrees, Gradient Boosting, and Gaussian Naive Bayes, were evaluated, with Gaussian Naive Bayes exhibiting the best performance. Radiomics features extracted from T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI scans, such as original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity and wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy, significantly enhanced predictive accuracy. SHAP analysis identified critical clinical features, including IMLL, INR, BMI, Cys C, and RDW-CV, in the predictive model. The model was validated and demonstrated excellent performance across multiple metrics. The clinical utility and interpretability of the model were further enhanced through the application of patient clustering and nomogram analysis. This model has the potential to serve as a reliable tool for clinicians in the formulation of personalized treatment plans and prognosis assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the application of machine learning technology in the medical field has become increasingly prevalent, particularly in disease prediction and patient rehabilitation assessment1,2. Acute spinal cord injury (ASCI) is a sudden traumatic event that typically results in severe neurological impairment and a significant decline in quality of life3,4. Early prediction of neurological recovery in ASCI patients is crucial for developing personalized treatment plans. However, current research still faces numerous challenges and limitations.

The existing ASCI prediction models can primarily be categorized into traditional machine learning methods and deep learning methods5,6. Traditional methods, such as logistic regression, decision trees, and random forests (RF), have advantages in interpretability and computational efficiency but typically rely on manual feature selection, which may overlook complex patterns in the data. Wilson et al. used a multivariable logistic regression model with clinical variables to predict the occurrence of acute inpatient complications, achieving an AUC of 0.75, indicating acceptable predictive performance7. However, this approach’s reliance on manual feature selection limits its applicability and generalizability. In addition, unsupervised machine learning techniques, such as k-means clustering, have demonstrated potential in handling large datasets with high-dimensional features in SCI recovery prediction, but their application to ASCI remains limited8. On the other hand, deep learning methods, like convolutional neural networks and recurrent neural networks, excel at handling high-dimensional and complex data. Peng et al. proposed a simple fully convolutional network that combines techniques such as data augmentation, pre-training, and model regularization to accurately predict brain age9. Nevertheless, the training process of deep learning methods requires large amounts of annotated data and computational resources, posing a significant challenge due to the high cost of data acquisition and annotation in the medical field.

Multimodal data fusion is another effective approach to improving predictive performance. Wilson et al. attempted to integrate imaging data with clinical data to enhance predictive accuracy. Their results indicated that integrating acute clinical and imaging information into predictive models significantly improved the accuracy of predicting functional independence in SCI patients at a one-year follow-up10. Recent studies have also explored the use of serological biomarkers, RNA profiles, and MRI-based radiomics as prognostic tools for ASCI. For instance, RNA transcriptomics has shown promise in predicting ASIA impairment scale grades with an accuracy of 72.7%, while serological markers such as neurofilament light chain and glial fibrillary acidic protein have demonstrated potential in predicting long-term motor function recovery11,12. The synergistic effect of VEGF and SDF-1α on endothelial progenitor cells has also been studied, indicating that these molecular markers may play a role in promoting vascular recovery and could potentially be integrated into future predictive models for ASCI13. In parallel, recent advancements in interpretable machine learning models, such as the CCIS-MVQA model for medical visual question answering, have enhanced prediction accuracy by incorporating counterfactual causal reasoning14. Additionally, the Multi-Omics Meta-Learning Algorithm (MUMA) employs self-adaptive sample weighting and interaction-based regularization, demonstrating superior performance in classifying biological samples and identifying relevant biomarkers from noisy multi-omics data15. Moreover, image-guided surgical approaches, such as the para-corticospinal tract approach for hematoma evacuation in intracerebral hemorrhage patients, offer potential for improving functional outcomes by preserving vital neural pathways16. However, these approaches are often limited by the lack of integration into interpretable and clinically practical machine learning frameworks.

Recent advancements in algebraic graph theory and mathematical structures have contributed significantly to solving complex, multidimensional problems in various fields, including medical data analysis. For instance, recent studies have utilized graph-theoretical methods, such as loop-involutions and inverse graphs, to model relationships between data points in a highly structured manner. This mathematical approach has been shown to improve predictive performance by incorporating topological indices, thus aiding in the refinement of predictive models in clinical settings. These developments offer valuable insights for structuring multimodal medical data in predictive modeling, enabling the creation of more accurate and interpretable models for conditions such as acute spinal cord injury (ASCI). The integration of Koszul algebra, circulant matrices, and cycles—as explored in recent studies—offers additional algebraic structures that can optimize the understanding of data connections and patterns, further improving predictive accuracy in complex clinical environments17,18.

Despite numerous advancements in ASCI prediction research, several challenges remain. Existing methods still face limitations in predictive accuracy and generalizability, with many studies relying on limited feature sets that overlook the importance of individual patient differences. Moreover, the interpretability and clinical applicability of the models require further investigation. While complex deep learning models achieve high accuracy, their lack of transparency makes it difficult for clinicians to understand the decision-making process of the models. For example, traditional model evaluation metrics, such as AUROC, may overemphasize common events, leading to skewed performance assessments in imbalanced datasets8. To address these challenges, this study represents the first systematic attempt to apply multiple well-documented machine learning methods, including advanced algorithms and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) analysis, specifically to ASCI for predicting neurological recovery. While these methods have been extensively used in other medical domains, their application in ASCI remains unexplored. By incorporating imaging, radiomics, serological, and clinical data, we aim to leverage multimodal information to enhance predictive performance and robustness. Additionally, we employed internal validation techniques such as cross-validation and grid search to evaluate model performance, ensuring its robustness and reproducibility. To enhance the model’s clinical applicability, we incorporated interpretability techniques, such as SHAP values, to help clinicians better understand the model’s decision-making process. We also developed and deployed an online platform that integrates the model, providing real-time prediction services, thereby allowing healthcare professionals and patients to conveniently access and use the prediction tool. This approach addresses both methodological challenges, such as data heterogeneity and model interpretability, and clinical gaps, such as the need for personalized treatment strategies in ASCI.

Methods

Study design

The objective of this retrospective cohort study is to develop and validate a machine learning-based predictive model for postoperative functional recovery in patients with ASCI. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi’an Honghui Hospital with reference number [No. 20240305] and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The committee waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective design and anonymized data, ensuring patient confidentiality. Figure 1 illustrates our research process and framework.

Study population

The study cohort comprised 387 patients with ASCI who underwent surgical treatment at Xi’an Honghui Hospital. The inclusion criteria for these patients were as follows: age over 18 years and time from injury to surgery less than 7 days. Exclusion criteria included: non-traumatic SCI cases, patients without preoperative or postoperative American Spinal Injury Association (AIS) grading in medical records, cases with more than 10% missing variables, and patients with consciousness disorders, coma, dementia, or death. Among these, 142 patients had preoperative T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI scans that met the quality requirements for region-of-interest (ROI) delineation and radiomics feature extraction. The remaining 245 patients were excluded from radiomics analysis due to the absence of MRI scans or suboptimal imaging quality. For analyses not involving radiomics features, all 387 patients were included. For multimodal analyses, the selected radiomics features from the 142 patients were combined with clinical and laboratory features to create a unified dataset for machine learning.

Data collection

Clinical data, including patient demographics (age, gender), injury severity, and preoperative and postoperative functional scores (e.g., AIS grading), were retrieved from the hospital’s electronic medical record system. Laboratory test results, such as key biochemical and hematological markers, were extracted from the Laboratory Information System (LIS). Preoperative imaging data were collected in the form of T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI scans. For the subset of 142 patients with suitable imaging data, lesion areas corresponding to spinal cord injuries were manually delineated by an experienced radiologist with over 20 years of clinical experience, following standardized protocols to ensure reproducibility. Radiomics features were extracted from these delineated areas using the PyRadiomics toolkit, adhering to the Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IBSI) guidelines. Extracted features included shape descriptors, first-order statistics, and texture features.

Data preprocessing

To prevent data leakage, we first split the data into training and testing sets in a 7:3 ratio using stratified sampling to preserve the distribution of AIS grades across the splits. Preprocessed steps included outlier handling and missing value imputation, and standardization. Outliers were replaced using the interquartile range (IQR) method, and categorical variables were standardized. Missing values were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations with the RF method (m = 5), ensuring data integrity and consistency19. Statistical analyses were conducted to validate data integrity. Normality testing for numerical variables was performed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables with normal distributions were compared using t-tests, while those with non-normal distributions were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests. For multimodal analysis, clinical and laboratory data, along with imaging-derived lesion length, were preprocessed together, while radiomics features underwent a separate preprocessing workflow to address their high dimensionality and specific requirements for quality control. Graph theory and edge labeling techniques, such as those explored by Hazzazi et al.20, have shown significant promise in understanding complex algebraic structures like Moufang quasigroups. These methodologies can be adapted for use in analyzing the relationships within multimodal data sets, as in our approach to SCI recovery prediction.

Feature selection

Given the high dimensionality of radiomics features (over 1,600 extracted features), an independent analysis was conducted to identify the most predictive features. Preprocessing steps included standardization to zero mean and unit variance, followed by the exclusion of features with a high proportion of missing values (> 50%) or low variance to ensure data quality. Univariate analysis using ANOVA was applied to retain radiomics features significantly associated with the target variable (p < 0.05), and Lasso regression with cross-validation was subsequently employed to further refine the selection, yielding a subset of key predictive radiomics features. Separately, clinical and laboratory data, along with imaging-derived lesion length, were analyzed as part of the multimodal dataset, where Lasso regression was used to perform feature selection and model training simultaneously. The optimal regularization parameter (λ) was determined through cross-validation to balance model complexity and predictive performance. After selecting the most relevant features, the key radiomics features from the subset of 142 patients were integrated with the selected clinical and laboratory features to construct a unified multimodal dataset. This combined dataset ensured dimensionality reduction and feature relevance while maintaining a robust framework for predictive analysis.

Machine learning and model evaluation

Machine learning models were initially trained and validated using the full cohort of 387 patients, incorporating clinical and laboratory features. This analysis aimed to evaluate the predictive potential of these features for estimating postoperative functional recovery. To further enhance the predictive performance, additional radiomics features extracted from preoperative imaging were integrated into the analysis. A subset of 142 patients with high-quality imaging data was used to construct a multimodal dataset combining radiomics, clinical, and laboratory features. This approach enabled a comprehensive assessment of the added value of radiomics features in improving prediction accuracy.

We divided the training data into training and internal validation sets in an 8:2 ratio. The model was trained on the training set and evaluated and validated on the internal validation set, with final model performance validated on the test set. Various machine learning algorithms were used to construct predictive models, including XGBoost, Logistic Regression, K-nearest neighbors (KNN), support vector machines (SVM), Decision Tree, RF, LightGBM, ExtraTrees, Gradient Boosting, and Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB). Model hyperparameters were optimized through grid search and cross-validation, and the optimized hyperparameters were used for analysis. The Stacking method was employed to integrate these models, further enhancing predictive performance. The models were comprehensively evaluated using metrics such as ROC curve, AUC value, accuracy, recall, precision, F1 score, Kappa coefficient, Matthew’s correlation coefficient (MCC), and Brier score. The model with the best performance was selected for further analysis. Detailed hyperparameter configurations are provided in the supplementary materials.

Model interpretation

We interpreted the prediction results using the optimal model identified. SHAP values were employed to analyze the feature importance, illustrating the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions. The SHAP interpreter was used to compute SHAP values for the training set and generate feature importance plots, providing a more intuitive understanding of the model’s decision-making process, thus ensuring the model’s transparency and interpretability.

Patient clustering analysis

Based on the SHAP values for each patient’s indicators, we conducted a clustering analysis to categorize the patients into different groups. Hierarchical clustering was performed using the ConsensusClusterPlus package21, with 80% of samples and features repeatedly resampled. The optimal number of clusters was determined by setting the maximum K value and the number of repetitions. The clustering results were then outputted for further analysis and validation of patient groupings.

Nomogram construction

Both static and dynamic nomograms were constructed. The static nomogram was based on predictions from the Gradient Boosting model and visualized using a logistic regression model. The dynamic nomogram displayed feature inputs and prediction results through a front-end interface built with HTML and JavaScript, while the back-end used Flask to handle prediction requests, enabling real-time predictive visualization.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R and Python. Group characteristics were compared using t-tests and chi-square tests, and feature selection was performed using Lasso. Multiple model building, model tuning, and integration were carried out. Model interpretation was conducted using SHAP values, and patient clustering analysis and nomogram construction were performed to evaluate the impact on postoperative recovery.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Among the 387 eligible patients with ASCI, the improvement group included 137 patients, with a median intramedullary lesion length (IMLL) of 42.270 mm (IQR: 28.800–55.070), a median age of 53.0 years (IQR: 44.0–59.0), and a median RDW-CV of 13.000 (IQR: 12.000–13.000). The non-improvement group included 250 patients, with a median IMLL of 57.900 mm (IQR: 40.225–77.965), a median age of 54.0 years (IQR: 44.0–62.0), and a median RDW-CV of 13.200 (IQR: 12.000–13.200) (Table 1). For each patient’s laboratory test data, we used the earliest available test results obtained after admission for statistical analysis. Significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of AIS classification (p = 0.01), IMLL (p < 0.01), preoperative risk assessment (PRA) classification (p = 0.01), and RDW-CV (p = 0.01). Other characteristics such as gender, continuous oxygen inhalation (COI), and intraoperative transfusion (IT) showed no significant differences between the two groups.

The training set comprised 271 samples, with 95 patients (35.06%) showing postoperative neurological improvement and 176 patients (64.94%) showing no improvement. The test set comprised 116 samples, with 42 patients (36.21%) showing postoperative neurological improvement and 74 patients (63.79%) showing no improvement. The missing rates for all features, except BMI, were no more than 10%, while the missing rate for BMI did not exceed 25% (Fig. 2A-D).

Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection Process (A-D) Density distribution plots of variables after multiple imputation of missing values using the MICE package. (E) Lasso regression coefficient path illustrating the trajectories of each variable’s coefficients with changes in the regularization parameter Log Lambda. (F) Deviation diagnosis plot of the Lasso regression model showing changes in deviation with different Log(λ) values. IMLL, Intramedullary lesion length; RBC, Red blood cell; FDP, Fibrinogen degradation products; K, Kalium; Cl, Chlorine; Na, Natrium; BMI, Body Mass Index; P-LCR, Platelet-large cell ratio, MPV, Mean platelet volume; PDW, Platelet distribution width; PCT, Plateletcrit.

Feature selection

For clinical and laboratory features, Lasso regression was used to perform feature selection. By adjusting the regularization parameter λ, the most predictive features for the model were selected. Figure 2E illustrates the Lasso regression coefficient path, and Fig. 2F shows the optimal λ value selected through cross-validation (λ = 0.0412). The final selected features included IMLL, PRA, charlson weight (CW), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), cystatin C (Cys C), international normalized ratio (INR), RDW-CV, Urea, and BMI, which significantly contributed to the model’s predictive performance.

For radiomics features, a total of 1,690 features were extracted from the T2-weighted fat-suppressed MRI scans of 142 patients. After preprocessing, including removal of constant-value features, high-correlation filtering (correlation threshold > 0.9), and univariate statistical analysis, the number of features was reduced to 314. Statistical tests identified eight significant features with p-values < 0.05, with the top features ranked by F-score including original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity (F = 7.91, p = 0.0056), wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy (F = 7.01, p = 0.0090), and lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity (F = 6.85, p = 0.0098) (Supplementary Table S1). Using Lasso regression with cross-validation, six key radiomics features were ultimately selected for inclusion in the multimodal dataset: original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy, lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity, lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelVariance, wavelet-LLL_glrlm_LongRunHighGrayLevelEmphasis, and wavelet-LLH_firstorder_Kurtosis. These features, combined with the selected clinical and laboratory features, formed the final dataset for machine learning model development.

Model construction and evaluation

In this study, various machine learning models were constructed, including XGBoost, Logistic Regression, KNN, SVM, Decision Tree, RF, LightGBM, ExtraTrees, Gradient Boosting, and GNB. These models were integrated using the Stacking method. Model performance was evaluated using ROC curves and AUC values (Figs. 3A-B and 4A-B), and further validated with precision-recall curves (Figs. 3C-D and 4C-D), decision curve analysis (Figs. 3E-F and 4E-F), calibration curves (Figs. 3G-H and 4G-H), and learning curves (Figs. 5 and 6). Comprehensive evaluation showed that the Gradient Boosting model performed best across all metrics in the analysis based on 387 patients, achieving an accuracy of 0.75, an AUC of 0.79, a recall of 0.55, a precision of 0.69, an F1 score of 0.61, a Kappa coefficient of 0.43, an MCC of 0.43, and a Brier score of 0.24 (Table 2). With the inclusion of multimodal radiomics data, model performance improved significantly. GNB emerged as the superior model, achieving the highest AUC of 0.90, an accuracy of 0.80, a recall and precision of 0.67, an F1 score of 0.67, a Kappa coefficient of 0.52, and an MCC of 0.52. These results highlight the advantages of incorporating multimodal data into machine learning models. Notably, AUC heatmap analyses of feature combinations (Supplementary Fig. 1) demonstrated that integrating radiomics with laboratory, clinical, or imaging data significantly enhanced the AUC values for both training and test datasets. The highest AUC of 0.90 was achieved when combining all feature types, suggesting that radiomics data contributes to a more accurate and reliable model. These improvements underline the potential of radiomics-based multimodal approaches for enhancing predictive accuracy in clinical applications. Additionally, the Stacking model demonstrated competitive performance, with an accuracy of 0.75 and an AUC of 0.81, underscoring its robustness (Table 3). These findings underscore the transformative potential of radiomics-based multimodal analysis, with GNB emerging as the most reliable model for predicting postoperative neurological outcomes.

Model Performance Evaluation with Clinical and Laboratory Data. (A) ROC curve on the validation dataset. (B) ROC curve on the test dataset. (C) Precision-Recall curve on the validation dataset. (D) Precision-Recall curve on the test dataset. (E) Decision curve on the validation dataset. (F) Decision curve on the test dataset. (G) Calibration curve on the validation dataset. (H) Calibration curve on the test dataset. LightGBM, light gradient boosting machine; SVM, Support Vector Machine; KNN, K-nearest neighbor.

Model Performance Evaluation with Multimodal Data Including Radiomics Features. (A) ROC curve on the validation dataset. (B) ROC curve on the test dataset. (C) Precision-Recall curve on the validation dataset. (D) Precision-Recall curve on the test dataset. (E) Decision curve on the validation dataset. (F) Decision curve on the test dataset. (G) Calibration curve on the validation dataset. (H) Calibration curve on the test dataset. LightGBM, light gradient boosting machine; SVM, Support Vector Machine; KNN, K-nearest neighbor.

Learning Curves of Different Models with Clinical and Laboratory Data. Each subplot shows the changes in training scores and validation scores with varying numbers of training samples, used to evaluate the generalization performance of each model. LightGBM, light gradient boosting machine; KNN, K-nearest neighbor; SVM, Support Vector Machine.

Learning Curves of Different Models with Multimodal Data Including Radiomics Features. Each subplot shows the changes in training scores and validation scores with varying numbers of training samples, used to evaluate the generalization performance of each model. LightGBM, light gradient boosting machine; KNN, K-nearest neighbor; SVM, Support Vector Machine.

Model interpretability and feature importance

We conducted SHAP analysis to assess the feature contributions of the GNB model, the optimal model identified after integrating multimodal data. The SHAP summary plot (Fig. 7A) shows that the most influential features are original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity (+ 0.088), wavelet-LLL_glrlm_LongRunHighGrayLevelEmphasis (+ 0.083), and lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity (+ 0.081), followed by clinical features such as IMLL (+ 0.067) and RDW_CV (+ 0.042). These findings underscore the significant contribution of radiomics features in enhancing model performance, with these features consistently ranking as the top predictors. The SHAP feature importance plot (Fig. 7B) further illustrates how these features influence the model’s output, with the original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity and lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity exhibiting substantial effects on prediction, particularly in terms of increasing or decreasing the likelihood of a favorable neurological outcome. The overall decision plot (Fig. 7C) illustrates how changes in feature values affect the model’s overall predictions. The SHAP heatmap (Fig. 7D) visualizes the influence of features on model predictions across patients. The intensity of red and blue indicates the positive or negative impact of each feature, respectively. original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, wavelet-LLL_glrlm_LongRunHighGrayLevelEmphasis, and lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity exhibit the most substantial effects on model output. IMLL and RDW_CV also play significant roles, with variations in these features directly influencing recovery predictions. This plot highlights the joint effects of clinical and radiomics features on predictive accuracy, providing a clearer understanding of their contributions. The SHAP waterfall plots (Fig. 7E) for a specific patient shows that original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity (+ 0.32) and lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity (+ 0.31) have the most significant positive contributions, while IMLL (+ 0.03) supports a favorable prediction. Wavelet-LLL_glrlm_LongRunHighGrayLevelEmphasis (−0.02) exerts a minor negative effect. In Fig. 7F, for another patient, IMLL (−0.08) and wavelet-LLL_glrlm_LongRunHighGrayLevelEmphasis (−0.04) dominate the negative prediction.

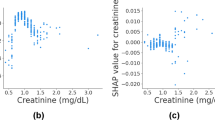

Furthermore, the SHAP dependence plot (Supplementary Fig. 2) identify key thresholds for several clinical and radiomics features that significantly influence the model’s predictions. For IMLL, a threshold of 62 mm was identified, above which patients tend to experience poorer neurological outcomes. Similarly, lower values of BMI and Cys C were associated with more favorable recovery, with thresholds of 22.5 for BMI and 0.85 mg/L for Cys C, below which positive predictions were more likely. For RDW_CV, values below 13.5 were associated with improved neurological recovery, marking a critical cutoff for positive outcomes. These findings emphasize the importance of specific feature values in guiding the model’s decision-making process and highlight clinically relevant thresholds that could inform treatment decisions. Additionally, the decision tree visualization (Supplementary Fig. 3) demonstrates how both radiomics and clinical features interact to predict neurological outcomes. The decision tree reveals IMLL, eGFR, and BMI as key decision points, with radiomics features like wavelet-LLL_glrlm_LongRunHighGrayLevelEmphasis influencing the early stages of classification. This reinforces the idea that both imaging and clinical factors play crucial roles in making accurate predictions. Further details regarding the decision tree structure and the contributions of individual features are provided in the supplementary results section, where the tree nodes and relevant thresholds are described in detail.

Model Feature Importance and Interpretability Analysis. (A) Feature importance bar plot, displaying the average SHAP value of each feature and its impact on the model output. The X-axis represents the average SHAP value, and the Y-axis represents the feature names. (B) SHAP value scatter plot, displaying the distribution of SHAP values for each feature and their impact on the model output. The X-axis represents the SHAP values, and the Y-axis represents the feature names, with color indicating the feature value magnitude (red for high values, blue for low values). (C) Overall decision plot, illustrating the SHAP values of all features and their impact on the overall model prediction. The X-axis represents the SHAP values, and the Y-axis represents the feature names. (D) Heatmap of feature SHAP values, showing the distribution of SHAP values for each feature across samples. The color indicates the magnitude of SHAP values (red for positive impact, blue for negative impact). (E) SHAP waterfall plot for a patient with a positive contribution. (F) SHAP waterfall plot for a patient with a negative contribution. (E-F) These plots demonstrate how feature values influence the prediction outcomes for individual patients and display the specific contribution values of each feature to the patient’s prediction outcome. SHAP, Shapley Additive Explanations; IMLL, Intramedullary lesion length; INR, International normalized ratio; BMI, Body Mass Index; Cys C, cystatin C; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; RDW-CV, Red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation; CW, Charlson weight; PRA, Preoperative risk assessment.

Patient clustering

We performed clustering analysis based on the SHAP values of each patient’s indicators, dividing the patients into two distinct groups (Fig. 8). The consensus matrix (Fig. 8A) and the CDF plot (Fig. 8B) demonstrated the stability of the two clusters, with the delta area plot (Fig. 8C) confirming the optimal number of clusters as K = 2. The PCA plot (Fig. 8D) further confirmed a clear separation between cluster A and cluster B along the principal components. The heatmap (Fig. 8E) displayed the distribution of critical features, ncluding original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy, lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity, IMLL, PRA, CW, eGFR, Cys C, INR, RDW-CV, Urea, BMI, and others, across the clusters. These feature distributions highlight meaningful differences between the two groups, offering insights into their clinical and radiomic profiles. The clustering analysis based on SHAP values provide valuable guidance for personalized treatment and prognosis assessment.

Clustering Analysis Based on Patient SHAP values. (A-C) Unsupervised consensus clustering analysis. The plots showing the consistency distribution of patients under different numbers of clusters and the changes in the cumulative distribution function (CDF) curves. (D) Principal component analysis (PCA) scatter plot, the PCA scatter plot illustrating the distribution of the two patient clusters based on PCA, with red representing cluster A and blue representing cluster B. (E) SHAP value heatmap. The heatmap displaying the distribution of SHAP values for different features in the two patient clusters, with color indicating the magnitude of SHAP values (red for high values, blue for low values).

Nomogram analysis

We constructed a nomogram integrating key clinical and radiomic indicators to estimate the probability of neurological recovery. As shown in Fig. 9A, the nomogram incorporates critical features such as BMI, Urea, RDW-CV, INR, Cys C, eGFR, PRA, and IMLL, alongside radiomics features including original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy, lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity, and wavelet-LLH_firstorder_Kurtosis. The distribution of points highlights the differential contributions of these features to the overall prediction model, with BMI, Urea, and IMLL demonstrating the highest relative weights, indicative of their pivotal roles in influencing neurological outcomes. In contrast, features such as original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity and wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy exhibit smaller contributions, reflecting their more limited influence on the model’s predictive accuracy. Figure 9B and C display the decision curve analysis and clinical impact curve, which evaluate the net clinical benefits of the model at different decision thresholds, verifying the model’s practicality in clinical settings. The calibration curve in Fig. 9D shows the fit between the predicted probabilities and the actual incidence, indicating a high consistency between the model’s predictions and the actual outcomes. The dynamic nomogram (Fig. 9E) provides an interactive tool that allows clinicians to input specific patient characteristics and obtain real-time prognostic assessments. The nomogram combines static and dynamic display methods, offering a comprehensive model interpretation and prediction evaluation tool, which helps to enhance the accuracy and reliability of clinical decision-making.

Risk Prediction and Evaluation Model (A) Simple Nomogram. The nomogram integrates key clinical and radiomic features, including BMI, Urea, RDW-CV, INR, Cys C, eGFR, CW, PRA, IMLL, and radiomic features such as original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy, and wavelet-LLH_firstorder_Kurtosis, to calculate the overall risk score. The total score corresponds to the probability of neurological recovery. (B) Decision curve analysis illustrating the net benefit of the model at different thresholds. (C) High-risk threshold analysis displaying the number of high-risk patients and the actual number of events at different high-risk thresholds. (D) Calibration curve comparing the consistency between the model’s predicted probabilities and the actual occurrence probabilities. (E) Dynamic Nomogram, the dynamic nomogram presenting individual risk predictions for Patient 1, Patient 2, and Patient 3, with input feature values including BMI, CysC, IMLL, and INR, showing the predicted risk probabilities for each patient. INR, International normalized ratio; BMI, Body Mass Index; Cys C, cystatin C; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; RDW-CV, IMLL, Intramedullary lesion length; Red blood cell distribution width-coefficient of variation.

Discussion

This study employed various machine learning algorithms and SHAP analysis to predict neurological recovery in ASCI patients. The results demonstrated that the GNB model outperformed all other models across all evaluation metrics, achieving an AUC of 0.90, accuracy of 0.80, and precision of 0.67. The GNB model, when integrating clinical, laboratory, and radiomics features, demonstrated strong predictive power, especially when compared to traditional models such as Gradient Boosting and Logistic Regression. This multimodal approach not only improved diagnostic consistency and reliability but also significantly enhanced predictive performance, particularly for early-stage detection of SCI recovery. The model’s higher AUC compared to traditional diagnostic methods indicates a substantial improvement in accuracy, with the potential to reduce the risk of misdiagnosis and improve patient outcomes in clinical settings.

SHAP analysis provided valuable insights into the contributions of individual features and their interactions, offering a deeper understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying ASCI. In this study, SHAP was used for model interpretability, providing a unified measure of feature importance with both global and local explanations. By attributing Shapley values to each feature based on its contribution to the model, SHAP proved particularly useful for understanding complex interactions within multimodal data22. It was preferred over LIME due to its consistency and ability to handle non-linear relationships more effectively. SHAP’s capability to capture a broader set of relevant features allows for a more detailed and accurate explanation of individual predictions, making it the ideal choice for this study’s need for a holistic understanding of model behavior23.

Among the clinical and laboratory features, IMLL emerged as the most significant predictor, demonstrating a negative correlation with neurological recovery. Longer IMLL values were associated with more severe SCI and poorer recovery. A critical threshold of 62 mm for IMLL indicated that recovery rates significantly decreased beyond this point, which is consistent with previous studies, such as Kamal et al., where IMLL > 60 mm was similarly linked to poor recovery24. Additional clinical and laboratory feature, such as INR, BMI, and Cys C, also played key roles in predicting recovery outcomes. INR showed a negative correlation with neurological recovery. Higher INR values may indicate coagulopathy in patients, increasing the risk of postoperative complications and thereby affecting neurological recovery. Previous research has also highlighted that coagulopathy is associated with poor prognosis in SCI patients25. Higher BMI values were linked to poorer postoperative recovery, as obesity is associated with various metabolic disorders that hinder nerve regeneration and functional recovery. Previous studies have indicated that obese patients face more challenges during recovery from SCI26,27. The inclusion of Cys C further enriched the model, with a threshold of 0.77 mg/L, correlating with impaired recovery. Elevated Cys C levels, significantly higher in SCI patients compared to normal subjects, highlight its role in the pathophysiological process of SCI28,29. These elevated levels are associated with kidney dysfunction and systemic inflammation, underscoring the critical role of renal function in recovery. Renal dysfunction, as indicated by high Cys C levels, significantly impacts SCI prognosis, suggesting that monitoring Cys C could provide valuable insights into patient recovery30.

Furthermore, RDW-CV, an indicator of red blood cell distribution width, showed predictive significance in SCI prognosis. RDW-CV values above 13.5% were associated with poorer prognosis, reflecting the systemic inflammatory status of SCI patients. Previous research has linked RDW-CV to chronic inflammation, cardiovascular diseases, and other health conditions, further supporting its relevance in SCI recovery31,32. Our results align with previous studies suggesting that RDW-CV > 12.6% is associated with an increased risk of death, particularly for those exceeding 13.9%31. This connection underscores the importance of inflammatory markers in predicting recovery outcomes and highlights RDW-CV as a significant predictor of long-term SCI recovery.

The integration of clinical and radiomics data has gained attention in various medical fields, particularly in oncology. Studies by Gan et al. and Yoo et al. demonstrated the benefits of combining clinical features with radiomics for improved prognostic predictions in breast and lung cancer23,33. However, this approach has been underexplored in SCI. This study addresses this gap by integrating clinical and radiomics features to enhance predictive accuracy for neurological recovery in ASCI patients.

In SCI, traditional models have primarily relied on clinical and laboratory data, with limited integration of imaging data. Radiomics, particularly features extracted from MRI scans, remains a relatively new frontier in SCI prognosis. While studies exploring the relationship between radiomics and SCI have begun, the integration of clinical, laboratory, and radiomics data remains rare. This study addresses this gap by combining these features, demonstrating that multimodal data integration significantly improves the prediction of neurological recovery in SCI patients. This approach aligns with recent studies, such as those by Gan et al.33, advocating for multimodal data to improve predictive models across various medical conditions.

The inclusion of radiomics features, such as original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy, and lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity, significantly enhanced model performance. These features, although not previously identified in SCI research, have been successfully applied in other diseases. For example, original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity has been shown to correlate with disease severity in coronary artery calcification34, and wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy has been crucial in distinguishing malignant from benign lesions in breast cancer35. This study demonstrates that combining radiomics features from T2-weighted MRI scans with clinical data results in a more accurate and reliable model for predicting neurological recovery in ASCI patients.

These results underscore the transformative potential of radiomics-based multimodal analysis, enhancing predictive accuracy and providing a deeper understanding of SCI pathology. Integrating features like original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity and wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy into SCI recovery models is consistent with findings from oncology and cardiovascular diseases, where radiomics has outperformed traditional imaging techniques35,36. By combining imaging biomarkers with clinical data, this approach facilitates more precise, personalized treatment strategies for ASCI patients. Furthermore, studies such as Sharafi et al. have reinforced the value of combining T1- and T2-weighted MRI radiomics with clinical features like age and hypertension for superior performance in SCI severity categorization37. This further supports the integration of both radiomic and clinical data to improve SCI recovery prediction models.

The SHAP-based clustering analysis further highlighted the distinct prognostic profiles of patients, dividing them into cluster A and cluster B. Significant differences were observed in clinical, laboratory, and radiomics features between the two clusters. Features such as IMLL, PRA, CW, eGFR, Cys C, INR, RDW-CV, Urea, and BMI, along with radiomics features like original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy, and lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity, showed substantial variations between the clusters. This multimodal clustering approach, which integrates both clinical/laboratory and radiomics features, aids clinicians in identifying patients with different prognostic risks, enabling the development of more targeted treatment plans. The clinical significance of the clustering results lies in providing more accurate risk assessment and personalized treatment guidance for clinicians, thereby improving treatment outcomes and patient prognosis.

This study also developed static and dynamic nomograms for clinical prediction and decision support. These tools can assist clinicians in quickly assessing patient prognosis and making more accurate treatment decisions in clinical practice38,39. The innovation of this study lies in the combination of various machine learning algorithms and SHAP analysis to comprehensively evaluate neurological recovery in patients with ASCI. This approach not only improved prediction accuracy but also revealed the contributions and interactions of each feature within the model. The static and dynamic nomograms provide practical tools for clinical decision support, facilitating the development of personalized treatment plans39.

Despite the significant findings of this study, several limitations exist. First, the relatively small sample size may affect the generalizability of the results. Second, the lack of an external validation set necessitates further verification of the model’s reliability and stability. Future studies should increase the sample size and conduct multi-center research to validate the applicability of our findings. Additionally, although we employed the Stacking method to integrate multiple models, the parameters did not yield optimal performance, and the method was ultimately not selected as the best model. In the presence of data noise and small sample size, the Stacking method may not fully realize its potential, resulting in performance instability and overfitting. Therefore, further expansion of the sample size is necessary.

The external validity and generalizability of our model are crucial considerations, particularly as this study was based on a cohort from a single hospital. The current findings demonstrate the potential of multimodal machine learning approaches in predicting SCI recovery but must be validated in other healthcare environments. As we are actively collaborating with additional hospitals, we plan to conduct external validation once the data from these institutions are sufficient. This will provide insights into the model’s performance across diverse patient populations and clinical settings. We aim to assess whether the model retains its predictive accuracy and clinical utility in hospitals with varying resources, healthcare infrastructure, and patient demographics.

In conclusion, this study developed an innovative machine learning model that integrates multiple algorithms and SHAP analysis to predict neurological recovery in patients with ASCI. By incorporating clinical, laboratory, and radiomics features, the model identifies key factors influencing recovery, including IMLL, INR, BMI, Cys C, and RDW-CV. Moreover, radiomics features such as original_glszm_SizeZoneNonUniformity, wavelet-HLL_glcm_SumEntropy, and lbp-3D-k_glszm_GrayLevelNonUniformity were crucial in improving the model’s predictive accuracy. The use of both static and dynamic nomograms highlights the model’s potential to assist clinicians in making accurate, individualized prognostic assessments. Ultimately, our proposed model offers a robust tool for predicting recovery in ASCI patients, potentially guiding the development of personalized treatment plans and improving clinical outcomes. Further validation in diverse clinical settings will be essential to confirm its generalizability and utility.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Olsen, C. R., Mentz, R. J., Anstrom, K. J., Page, D. & Patel, P. A. Clinical applications of machine learning in the diagnosis, classification, and prediction of heart failure. Am. Heart J. 229, 1–17 (2020).

Chang, M. C. et al. The use of artificial intelligence to predict the prognosis of patients undergoing central nervous system rehabilitation: A narrative review. Healthc. Basel Switz. 11, 2687 (2023).

Hayta, E. & Elden, H. Acute spinal cord injury: A review of pathophysiology and potential of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for Pharmacological intervention. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 87, 25–31 (2018).

Zwecker, M. et al. Assessment of the unmediated relationship between neurological impairment and health-related quality of life following spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 45, 293–300 (2022).

Sizheng, Z., Boxuan, H., Feng, X. & Dianying, Z. A functional outcome prediction model of acute traumatic spinal cord injury based on extreme gradient boost. J. Orthop. Surg. 17, 451 (2022).

Facchinello, Y., Beauséjour, M., Richard-Denis, A., Thompson, C. & Mac-Thiong, J. M. Use of regression tree analysis for predicting the functional outcome after traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 38, 1285–1291 (2021).

Wilson, J. R., Arnold, P. M., Singh, A., Kalsi-Ryan, S. & Fehlings, M. G. Clinical prediction model for acute inpatient complications after traumatic cervical spinal cord injury: a subanalysis from the surgical timing in acute spinal cord injury study. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 17, 46–51 (2012).

DeVries, Z. et al. Development of an unsupervised machine learning algorithm for the prognostication of walking ability in spinal cord injury patients. Spine J. Off J. North. Am. Spine Soc. 20, 213–224 (2020).

Peng, H., Gong, W., Beckmann, C. F., Vedaldi, A. & Smith, S. M. Accurate brain age prediction with lightweight deep neural networks. Med. Image Anal. 68, 101871 (2021).

Wilson, J. R. et al. A clinical prediction model for long-term functional outcome after traumatic spinal cord injury based on acute clinical and imaging factors. J. Neurotrauma. 29, 2263–2271 (2012).

Kyritsis, N. et al. Diagnostic blood RNA profiles for human acute spinal cord injury. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20201795 (2021).

Matthias, J. et al. Exploring the potential of routine serological markers in predicting neurological outcomes in spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 380, 114918 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Synergistic effect of VEGF and SDF-1α in endothelial progenitor cells and vascular smooth muscle cells. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 914347 (2022).

Cai, L., Fang, H., Xu, N. & Ren, B. Counterfactual Causal-Effect intervention for interpretable medical visual question answering. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging PP, (2024).

Huang, H. H., Shu, J. & Liang, Y. MUMA: a multi-omics meta-learning algorithm for data interpretation and classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. PP, (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Hematoma evacuation via Image-Guided Para-Corticospinal tract approach in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol. Ther. 10, 1001–1013 (2021).

A New Graphical Representation of the Old. Algebraic Structure - Nadeem – 2023 - Journal of Mathematics - Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4333301

Nadeem, M. et al. A Class of Koszul Algebra and Some Homological Invariants through Circulant Matrices and Cycles. J. Math. 4450488 (2022). (2022).

Blazek, K., van Zwieten, A., Saglimbene, V. & Teixeira-Pinto A. A practical guide to multiple imputation of missing data in nephrology. Kidney Int. 99, 68–74 (2021).

Hazzazi, M. M., Nadeem, M., Kamran, M., Naci Cangul, I. & Akhter, J. Holomorphism and Edge Labeling: An Inner Study of Latin Squares Associated with Antiautomorphic Inverse Property Moufang Quasigroups with Applications. Complexity 8575569 (2024). (2024).

Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinforma Oxf. Engl. 26, 1572–1573 (2010).

Li, X. et al. Efficient Shapley explanation for features importance Estimation under uncertainty. Med. Image Comput. Comput. -Assist Interv MICCAI Int. Conf. Med. Image Comput. Comput. -Assist Interv. 12261, 792–801 (2020).

Ji, H. et al. Integrating clinical data and medical imaging in lung cancer: feasibility study using the observational medical outcomes partnership common data model extension. JMIR Med. Inf. 12, e59187 (2024).

Kamal, R., Verma, H., Narasimhaiah, S. & Chopra, S. Predicting the role of preoperative intramedullary lesion length and early decompressive surgery in ASIA impairment scale grade improvement following subaxial traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurol. Surg. Part. Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 84, 144–156 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Identification of coagulation diagnostic biomarkers related to the severity of spinal cord injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 137, 112505 (2024).

Chen, Y., Henson, S., Jackson, A. B. & Richards, J. S. Obesity intervention in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 44, 82–91 (2006).

Blackmer, J. & Marshall, S. Obesity and spinal cord injury: an observational study. Spinal Cord. 35, 245–247 (1997).

Zhang, J. et al. Serum Cystatin C is increased in acute spinal cord injury: a multicentre retrospective study. Spinal Cord. 58, 341–347 (2020).

Lassus, J., Harjola, V. P. & Cystatin, C. A step forward in assessing kidney function and cardiovascular risk. Heart Fail. Rev. 17, 251–261 (2012).

Osei-Owusu, P., Collyer, E., Dahlen, S. A., Adams, R. E. & Tom, V. J. Maladaptation of renal hemodynamics contributes to kidney dysfunction resulting from thoracic spinal cord injury in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 323, F120–F140 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Association between elevated preoperative red cell distribution width and mortality after brain tumor craniotomy. Neurosurg. Rev. 47, 237 (2024).

Duarte-Gamas, L. et al. Red blood cell distribution width as a 5-Year prognostic marker in patients submitted to carotid endarterectomy. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Extra. 10, 181–192 (2020).

Gan, L. et al. A Clinical-Radiomics model for predicting axillary pathologic complete response in breast Cancer with axillary lymph node metastases. Front. Oncol. 11, 786346 (2021).

Mundt, P. et al. Analysis of epicardial adipose tissue texture in relation to coronary artery calcification in PCCT: the EAT signature! Diagn. Basel Switz. 14, 277 (2024).

Cao, K. et al. Peri-lesion regions in differentiating suspicious breast calcification-only lesions specifically on contrast enhanced mammography. J. X-Ray Sci. Technol. 32, 583–596 (2024).

Pan, Z. et al. A subregion-based prediction model for local-regional recurrence risk in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 184, 109684 (2023).

Sharafi, A., Klein, A. P. & Koch, K. M. Quantitative MRI assessment of Post-Surgical spinal cord injury through radiomic analysis. J. Imaging. 10, 312 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Predicting peritumoral edema development after gamma knife radiosurgery of meningiomas using machine learning methods: a multicenter study. Eur. Radiol. 33, 8912–8924 (2023).

Miao, X. et al. A dynamic online nomogram for predicting the heterogeneity trajectories of frailty among elderly gastric cancer survivors. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 153, 104716 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients involved in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Ziqing Yan and Jingkun Liu; collected the data: Jiaojiao Tai, Hua Fu, Xiaowen Ma, Haiyan Li, Yang Li and Xinying Li; Formal analysis, Jiaojiao Tai, Yang Li and Yijun Xie; Methodology, Jiaojiao Tai, Linbang Wang and Yijun Xie; Software, Jiaojiao Tai, Yijun Xie and Xinying Li; Supervision, Ziqing Yan and Jingkun Liu; Visualization, Jiaojiao Tai and Jingkun Liu; Writing – original draft, Jiaojiao Tai and Linbang Wang; Writing – review & editing, Jiaojiao Tai, Jingkun Liu and Ziqing Yan, Investigation: Hua Fu, Xiaowen Ma and Haiyan Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi’an Honghui Hospital (No. 20240305).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tai, J., Wang, L., Xie, Y. et al. Research on multi-algorithm and explainable AI techniques for predictive modeling of acute spinal cord injury using multimodal data. Sci Rep 15, 18832 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93006-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93006-4