Abstract

With global warming and the acceleration of the water cycle, the frequency and severity of droughts have progressively increased. Although Southwest China is located inland, the combined effects of global climate change, regional climate anomalies, and human activities have led to a diversified set of driving mechanisms for meteorological droughts. Based on monthly global and regional meteorological factors (10 global factors and 8 regional factors) and land use/land cover data from 1948 to 2023, this study employs classical correlation analysis, wavelet analysis, and Bayesian principles to explore the temporal and spatial evolution characteristics of meteorological droughts in Southwest China, as well as their driving mechanisms. The results show that: (1) between 1948 and 2023, meteorological droughts in Southwest China exhibited a north-south (annual average, spring, and winter) or east-west decreasing trend (autumn) and alternating east-west intensity in summer. The drought frequency ranged from 0.35 to 0.39, generally showing a decreasing trend from southwest to northeast. (2) Global atmospheric circulation significantly influences meteorological droughts in Southwest China, especially during El Niño years, when global atmospheric circulation factors such as Nino 3.4 and SOI have a more prominent impact on drought, particularly in the summer and autumn. In contrast, during La Niña years, drought intensity and frequency are more pronounced in spring and autumn. Regional climate factors, particularly temperature and evapotranspiration, also have a significant effect on drought across different seasons, especially in winter and spring, when higher temperatures and evapotranspiration exacerbate droughts, and precipitation has a relatively weaker effect. (3) Land use changes significantly affect meteorological droughts in Southwest China, with a driving probability ranging from 0.39 to 0.42. Under different climate conditions, the driving probabilities of land use changes are ranked as follows: El Niño years (0.32–0.52) > Normal years (0.31–0.51) > La Niña years (0.27–0.50). In particular, land use changes such as the expansion of built-up areas and the reduction of farmland could intensify the frequency and severity of meteorological droughts in drought-prone areas. Additionally, the reduction of green spaces or forests may also exacerbate droughts, especially during the urbanization process. Notably, during El Niño years, the driving effect of various landforms on drought shows different skewed distributions. Therefore, this study clarifies, to some extent, the evolution and mechanisms of meteorological droughts in Southwest China and provides technical guidance and theoretical support for drought prevention and disaster relief efforts in the Karst region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drought is a major natural disaster that can have severe direct and indirect impacts on agriculture, ecological and environmental health, energy-related sectors, and the economy1,2. Over the past century, global climate change trends have become increasingly evident, leading to a gradual intensification of the frequency and severity of droughts worldwide. For instance, the economic losses caused by global droughts were estimated to be around $17.33 billion from 1980 to 2009, increasing to $25 billion between 2008 and 2017, far exceeding the losses caused by other natural disasters3,4. Particularly in the southwestern region of China, the severe lack of precipitation during 2009–2010 resulted in economic losses exceeding $3.5 billion, underscoring the urgent need for research on drought evolution in this region5. This study focuses on the mechanisms driving meteorological droughts in the karst regions of Southwest China, aiming to provide technical support for regional drought relief efforts.

Drought is typically classified into four types: meteorological drought, agricultural drought, hydrological drought, and socio-economic drought6. As the starting point of the drought chain, meteorological drought is mainly triggered by prolonged rainfall deficits, abnormally high temperatures, and decreased evapotranspiration in watersheds7,8. This type of drought can further influence the occurrence of agricultural and hydrological droughts, thereby impacting regional ecological and economic systems9,10. Therefore, an in-depth exploration of the mechanisms underlying meteorological drought is crucial for comprehensively understanding the occurrence and development of droughts. Water vapor in the atmosphere is a critical indicator of meteorological drought, primarily sourced from atmospheric circulation water vapor transport and regional evapotranspiration11,12. Investigating the impact of large-scale ocean-atmosphere patterns on regional rainfall is essential for drought monitoring and early warning, facilitating a better understanding of drought propagation mechanisms13.

Previous studies have shown that China’s rainfall is influenced by various large-scale ocean-atmosphere patterns, including the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)14. These patterns not only significantly affect the intensity and distribution of seasonal rainfall in China but also play an important role in the occurrence of extreme drought events15,16. However, most current research primarily focuses on the correlation between individual remote factors and drought, lacking comprehensive analyses of the coupling effects of multiple remote variables and human activities17. Additionally, most studies emphasize the overall region, with limited research on the unique karst basins of Southwest China, where distinct geomorphological features may result in significantly different mechanisms of meteorological drought formation compared to other areas. The karst landscape, characterized by its unique geological formations, uneven rainfall distribution, and complex groundwater systems, presents a particularly sensitive environment for drought dynamics18,19. In particular, the spatial heterogeneity in precipitation and the reliance on underground water systems in karst regions exacerbate the vulnerability to drought. This study aims to fill the research gap on the mechanisms of meteorological drought in the karst regions of Southwest China and provide scientific support and technical guidance for drought relief efforts in the region.

On the other hand, human activities, such as land use/land cover change (LULCC), play an increasingly important role in the evolution of meteorological drought20. Globally, over one-third of the Earth’s surface/natural land has been altered by human activities, and LULCC can influence regional climate change through various geophysical processes21. For example, urbanization has intensified the expansion of impervious surfaces, reducing groundwater recharge and increasing regional drought risks22. In rural areas, agricultural expansion and deforestation contribute to soil degradation, which reduces the natural moisture retention capacity of the land, further exacerbating drought conditions23. Particularly in karst regions, land use changes—such as agricultural encroachment and land reclamation—can significantly alter the hydrological cycle, intensifying the frequency and severity of drought events24. However, there is limited research on the specific impact of LULCC on meteorological drought in the karst regions of Southwest China, which is a key focus of this study.

In terms of quantitative indices for describing meteorological drought, the main ones currently include the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), and the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI)25,26. Among these, the SPEI is particularly suitable for drought monitoring and analysis in the context of global warming, as it accounts for multi-scale characteristics and the effects of temperature changes27,28. For instance, multi-temporal SPEI can more accurately describe the variations of meteorological drought at different time scales, providing a more precise basis for studying regional drought evolution29,30. Additionally, wavelet coherence (WTC) analysis is an effective method for exploring the mechanisms of drought propagation, as it can identify relationships between droughts across different time scales31. However, relying solely on WTC or classical correlation analysis may not fully quantify the multi-temporal scale relationships between meteorological drought and other drought types, necessitating a combination of multiple methods for comprehensive analysis9,32.

In summary, the objectives of this study include: (1) identifying the intensity, frequency, recurrence periods, and oscillation cycles of meteorological drought in Southwest China from 1948 to 2023; (2) analyzing the impact of human activities on the intensity and frequency of meteorological drought, with a particular focus on the role of LULCC; and (3) exploring the effects of LULCC on the drivers of meteorological drought in Southwest China in the context of global climate change and regional climate anomalies. This study aims to fill the research gap on the mechanisms of meteorological drought in the karst regions of Southwest China and to provide scientific support and technical guidance for drought relief efforts in the region.

Research area

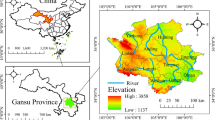

The study area is located in the typical karst distribution region of Southwest China, including parts of Guizhou, Yunnan, and Guangxi, with a total area of 352,526 km2. It encompasses 51 hydrological control basin sections, spanning a geographic range of 101°55′55″E to 110°55′45″E longitude and 22°42′57″N to 29°13′11″N latitude. Among these, Guizhou accounts for 37.97%, southeastern Yunnan for 25.36%, and northwestern and northern Guangxi for 36.67%. The study area has an average elevation of 848 m and features a climate transitioning between the northern subtropical humid zone and the southern subtropical semi-humid zone. The climatic characteristics include an annual average rainfall ranging from 600 to 1700 mm, temperature range of 10–23 °C (with a dew point of 12.05 °C), evaporation rates between 300 and 900 mm, annual average solar radiation intensity of 4831 MJ/m² (approximately 1341.95 h), atmospheric pressure of 864.05 hPa, and wind speed of 2.45 m/s. Despite abundant precipitation, its temporal and spatial distribution is uneven, providing a basis for meteorological drought research. The region is divided by the Wumeng Mountain-Miaoling range, with the northern part belonging to the Yangtze River basin and the southern part to the Pearl River basin. The topography and basin divisions play a crucial role in the interaction between karst landforms and meteorological drought. The primary land use types within the study area include forestland (60.2%), cultivated land (20.7%), grassland (16.1%), construction land (2%), and water bodies (0.98%). These land use characteristics significantly influence the regional hydrological processes and responses to climate change.

Research data and methods

Research data

Meteorological data

The regional meteorological data used in this study were primarily sourced from the Global Land Data Assimilation Systems (GLDAS, https://ldas.gsfc.nasa.gov/), which provided data at spatial resolutions of 0.25° × 0.25° and 0.1° × 0.1°. Specifically, monthly data from 1948 to 2023, including rainfall, temperature/dew point, potential evapotranspiration/relative humidity, pressure/wind speed, and solar radiation/duration, were obtained using these two resolution datasets. To validate the accuracy of these regional meteorological data, 51 hydrological/rainfall stations were selected from the China Meteorological Data Service Centre (http://data.cma.cn/site/index.html) (including 21 stations in Guizhou Province, 19 in Guangxi Province, and 11 in Yunnan Province). Comparative analyses and corrections were performed for specific periods of regional data to ensure their accuracy (Fig. 1).

Global meteorological data were mainly sourced from the Physical Sciences Laboratory (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/climateindices/list/), including monthly Nino 3.4, SOI, AMO, AO, MDI, MEI, NAO, NPI, PDO, and PNA data, with a time span also covering 1948–2023. All data were processed using the WGS84 coordinate system to ensure consistency and universality.

Spatial distribution map of hydrometeorological stations in the research areas. Map was created with ArcGIS version 10.3 (https://www.arcgis.com/).

Land use data

The land use data were sourced from multiple authoritative platforms, including the Resource and Environment Science and Data Center, China (http://www.resdc.cn), the National Earth System Science Data Center (http://www.geodata.cn), as well as other land use data-sharing platforms (such as http://www.nesdc.org.cn/; https://glovis.usgs.gov/; https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcoverexplorer/). Referring to the “National Remote Sensing Monitoring Land Use/Cover Classification System,” the land use types in Southwest China were refined into six categories: cultivated land (Cul_L), woodland (Woo_L), grassland (Gra_L), water body (Wat_L), construction land (Con_L) and unused land. The spatial resolution of the land use data is 30 m, and all data were processed using the WGS84 coordinate system for uniform analysis. The accuracy of the data was validated through comparison with field surveys and historical data correlations to ensure the reliability of the analysis results.

Elevation and hydrographic data

The elevation and hydrographic feature data of the watershed were automatically extracted using ArcGIS 10.3 from a 30-meter resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM, http://www.gscloud.cn/). This extraction was further analyzed and corrected using a comprehensive hydrogeological map to ensure the accuracy of the hydrographic network and watershed boundaries.

Research methods

SPEI calculation

The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) is a widely used drought index. In this study, monthly temperature and precipitation data were used as input to calculate the difference between monthly precipitation and potential evapotranspiration, followed by standard normal processing to obtain the SPEI. The specific steps of this method were as follows5,33,34:

Establishing the water surplus and deficit accumulation time series

Based on different time scales, such as annual, seasonal, or monthly, a corresponding water surplus and deficit accumulation time series was established:

In this formula, k represents the time scale (year/season/month), and n represents a specific year/season/month. Pi and Ei are the precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (units: mm) of the ith year/season/month, respectively.

Probability distribution fitting

To better describe the water surplus and deficit sequence, this study compared the fitting effects of distribution models such as Log-logistic, Pearson-III, Lognormal, and Generalized Extreme Value on the time series. The results indicate that the Log-logistic distribution provides the best fit. Its probability density function is:

Where α, β and γ are the scale, shape, and location parameters, respectively, obtained through the linear moment method.

Normalization of cumulative probability

The fitted cumulative probability is normalized to obtain the SPEI value.

When the cumulative probability P ≤ 0.5, the following formula is used for conversion:

When P > 0.5, convert to 1 − P and use the same formula for calculation:

Where c0=2.515517, c1 = 0.802853, c2 = 0.010328.

Classification of drought levels

According to the SPEI values, drought levels are classified into 5 categories (Table 1), with the specific classification criteria as follows:

Bayes principle

To explore the mechanism by which different land use types drive meteorological drought under the coupled effects of global climate change and regional/local climate anomaly scenarios (Cv), the probability of LULCCs driving drought in this study was calculated based on the Bayes principle, and the formula is below (for example, LaNiña year):

The probability of cultivated land driving drought under extreme anomaly scenario (Cv =1.5):

The probability of cultivated land driving drought under severe anomaly scenario (Cv =1.4):

The probability of cultivated land driving drought under moderate anomaly scenario (Cv =1.3):

The probability of cultivated land driving drought under mild anomaly scenario (Cv =1.2):

The probability of cultivated land driving drought under no anomaly scenario (Cv =1.1):

where X,Y are the regional/local climate anomaly and the meteorological drought index (SPEI) respectively; the process for calculating the probability of drought driven by other land use types was same as above, and that for normal/El Niño year was the same as above.

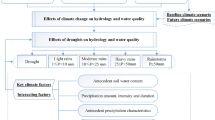

Analysis of drought mechanisms

To uncover the mechanisms of meteorological drought, this study employed one indicator, three periods, five scenarios, and six driving factors to explore the coupling relationship between global and local climate changes and human activities (Fig. 2). First, the study calculated the 3-month moving average based on the Nino 3.4 index to construct the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) (Fig. 11c). Subsequently, the period from 1948 to 2023 was divided into three periods based on a continuous five-month ONI17: Period 1: La Niña years (ONI ≤ -0.5 °C, Fig. 13a), Period 2: Normal years (-0.5 °C ≤ ONI ≤ 0.5 °C, Fig. 13b), and Period 3: El Niño years (ONI ≥ 0.5 °C, Fig. 13c).

Next, eight factors of local climate were used to calculate the coefficient of variation (Cv), and the geometric mean was derived to reflect the spatial distribution characteristics of local climate changes (anomalies) in Southwest China from 1948 to 2023 (Fig. 13). The natural breaks method was applied to classify these changes into five scenarios35: Normal scenario (Cv = 1.1), Mild Anomaly scenario (Cv = 1.2), Moderate Anomaly scenario (Cv = 1.3), Severe Anomaly scenario (Cv = 1.4), and Extreme Anomaly scenario (Cv = 1.5) (Fig. 13).

Finally, the study examined the driving effects of six land cover types on meteorological drought (SPEI) under five different scenarios. Due to the small proportion of unused land, it was excluded from the discussion. For a detailed methodological workflow, refer to Technical Flowchart 2.

Results and analysis

Climate change characteristics in Southwest China

As shown in Fig. 3, the spatial distribution of climate change in Southwest China during the period 1948–2023 was very regular. In particular, rainfall showed a decreasing trend in the annual average and spring/winter season, and a north-south decline in summer and autumn. The highest rainfall occurred in summer, and the lowest in winter, with an average annual rainfall of 601.65–1701.06 mm. The spatial distribution of temperature was similar to that of rainfall, with a decreasing trend from southeast to northwest in summer and autumn, and a north-south decline in the other seasons. The temperature difference among the four seasons was relatively small (11–12℃), with an average annual temperature of 10.47–22.37℃. The spatial distribution of evapotranspiration was relatively complex compared to rainfall and temperature, with an overall trend of strong–weak alternation in winter and summer and a north–south decrease in the annual average and in spring and autumn. The trend in the evaporation was in the order annual average > summer > spring > autumn > winter. The climate variability in Southwest China over annual and seasonal scales during the period 1948–2023 was also very regular (Fig. 4). Overall, the coefficient of variation (Cv) of rainfall over the annual and seasonal scales was the highest, followed by evapotranspiration, and that of temperature was the smallest (Fig. 4a-e). The Cv of temperature remained basically unchanged especially in summer (Fig. 4c), and was slightly higher than evaporation in winter (Fig. 4e). The monthly climate anomaly index could be divided into three periods (Fig. 8a), namely, an increasing/strengthening period in the January to April months, a sudden change/peak period in the May to September months, and a declining/weakening period. Among them, the climate anomaly index in the sudden change/peak period was in the order rainfall > evaporation > temperature, while the other two periods showed the opposite trend.

The Spatial distribution of rainfall(R), temperature (T), and evaporation (E) (annual and seasonal scales) .Map was created with ArcGIS version 10.3 (https://www.arcgis.com/).

The Coefficient of variation (Cv) of rainfall(R), temperature (T), and evaporation (E) (annual and seasonal scales) in 1948-2023. (Microsoft office Excel 2003, https://xiazai.zol.com.cn/detail/43/428458.shtml).

Characteristics of land use/land cover change in Southwest China

Overall, between 1948 and 2023, woodland accounted for the largest proportion of land use area in Southwest China (68.6%; 2020s), followed by cultivated land (26.7%; 1980s), with water bodies being the smallest (0.5%; 1970–1990 s) (Fig. 5a). In terms of interannual changes in land categories, the areas of cultivated land and grassland showed a decreasing trend (−46.17 km²/10a, 2010–2020 s; −56.39 km²/10a, 1970–1980 s), while the areas of other land categories showed an increasing trend. Among these, construction land grew the fastest (393.11 km²/10a, 2010–2020 s), while water bodies grew the slowest (0.07 km²/10a, 1970–1980 s). Interannual land type transitions were primarily characterized by the conversion of woodland to cultivated land (39,330.9 km²/10a, 1970–1980 s), followed by the conversion of cultivated land to woodland (33,213.6 km²/10a, 1970–1980 s), with the smallest transition being from water bodies to construction land (0.45 km²/10a, 1980–1990 s). The ranking of transition volumes is as follows: woodland (68.2% in 2010–2020 s) > cultivated land (26.2% in 1980–1990 s) > grassland (14.1% in 1970–1980 s) > construction land (5.6% in 2010–2020 s) > water body (1% in 2010–2020 s) (Fig. 5b-f).

The area proportion and transfer of land-use types in different periods. Map was created with origin version 2022 (https://www.originlab.com/).

Meteorological drought characteristics in Southwest China

Characteristics of meteorological drought intensity

The trends in the annual and seasonal meteorological drought in Southwest China from 1948 to 2023 mainly presented a decreasing pattern in the north–south (annual average and spring/winter) or east–west direction (autumn) and a strong–weak alternation in the east–west direction (summer) (Fig. 6), which is consistent with the spatial distribution of temperature and evapotranspiration. According to the drought level standards34, moderate, severe and extreme meteorological droughts occurred in Southwest China; particularly in autumn, the area proportion of moderate drought was 100%, and it was greater than 90% in the other seasons. The drought recurrence period was the longest for extreme drought, with 113.5 months in spring and 76.95 months in the annual average, and was the shortest for moderate drought, with 32.59 months in summer and 20.88 months in winter (Fig. 8b). Compared with the yearly and seasonal trends, meteorological drought at the monthly scale increased yearly. Especially after 1995, the drought level was mainly moderate or greater over 1–12 months (Fig. 7a). Severe drought was observed from January to June in 1950, 1955, 1960, and 1970 and 1980, and extreme drought was mainly observed in 1955 (Fig. 7a). The drought recurrence period at that monthly scale was in the order of extreme drought (68.07 months in Jun − 55.09 months in Sep) > severe drought (29.18 months in Nov − 19.41 months in May) > moderate drought (11.58 months in May − 8.57 months in Nov) (Fig. 8c).

The spatial distribution of drought intensity (I)/frequency (F) and Hurst index (H) in annual and seasonal scales. Map was created with ArcGIS version 10.3 (https://www.arcgis.com/).

The time series of drought intensity/frequency changes (monthly scale) (a,b), correlation coefficient (R) between global/local climate factors and SPEI (annual, seasonal, and monthly scales) (c,d). Map was created with Origin version 2022 (https://www.originlab.com/).

Characteristics of meteorological drought frequency

The meteorological drought frequency at the annual and seasonal scales in Southwest China from 1948 to 2023 was 0.35–0.39, with an overall decreasing trend in the south–north direction (Fig. 6). Moderate drought showed a relatively high frequency of 0.195 in autumn, the severe drought frequency was 0.12 in winter, and the extreme drought frequency was 0.05 on an annual scale and in spring. This occurred mainly because global warming may led to an increase in rainfall intensity and a decline in frequency in China36. An overall increasing trend was found in drought frequency in the 10-year moving mean value. The growth rate in the drought frequency was the highest (0.0298/10a) for the annual average, followed by that in summer and autumn (0.0227/10a, 0.027/10a), and was the slowest in spring and winter (0.0058/10a, 0.014/10a). The growth rate in the drought frequency at different levels was in the order of extreme drought (0.0233/10a in annual average) > moderate drought (0.0123/10a in summer) > severe drought (0.0085/10a in autumn). The drought frequency distribution on the monthly scale was relatively complex (Fig. 7b), with the highest from June to November in 2000 and 2009, followed by that from January to September in 1952 and 1980, and a relatively low from May to October in 1990 and August to December in 1979 (Fig. 7b). Figure 6 shows that the Hurst index of the SPEI in Southwest China was less than 0.5, indicating that it had a negative correlation with meteorological drought and showed sudden oscillations in 1948–2023, and the smaller the Hurst index was, the stronger the SPEI oscillation. The minimum Hurst index indicated that the SPEI oscillation was the strongest in autumn (0.12), with an east–west weakening trend, and was the exact opposite in summer, with an east–west strengthening pattern. The oscillation in the annual average SPEI gradually increased from northwest to southeast and showed an alternating north–south distribution in summer (Fig. 6).

The local climate anomalies and drought recurrence periods (annual, seasonal, and monthly scales). Map was created with Origin version 2022 (https://www.originlab.com/).

Meteorological drought mechanism in a karst drainage basin in Southwest China

The mechanism by which climate change drives meteorological drought in Southwest China

The impact of global climate change on meteorological drought

To investigate the driving mechanisms of global climate change on meteorological drought (SPEI) in Southwest China, this study calculated the Spearman correlation coefficients (R) between atmospheric circulation factors (a total of 10) and SPEI at annual, seasonal, and monthly scales (Fig. 7c). The results show that Nino 3.4, SOI, and MEI have the highest annual mean correlation coefficients with SPEI, which are 0.234, -0.242, and 0.24, respectively, and all pass the significance test (Sig. < 0.05). The influence of NAO and MDI on meteorological drought (SPEI) is most significant in the summer and autumn seasons (0.281, -0.286; Sig. < 0.05), while it is not significant in spring and winter (Sig. > 0.05). The impacts of Nino 3.4 in April (0.25), MDI in October (-0.386), and AMO (−0.24) and NAO (0.275) in September on meteorological drought also pass the significance test (Sig. < 0.05 or Sig. < 0.01).

To further reveal the driving mechanisms of global climate change on drought, this study selected atmospheric circulation factors that pass the significance test for wavelet analysis with SPEI (Fig. 9a-q). The analysis results indicate the following:

-

(1)

SPEI exhibits three significant oscillation cycles at annual and summer-autumn scales, all of which pass the 95% red noise test. On an annual scale, the main cycles of SPEI are 2.9-3.6 M (1954–1958), 2.6-3.4 M (1996–2000), and 15-36 M (1978–2002); in summer, the cycles are 3-3.9 M (1964–1972), 2.7-3.3 M (1995–1996), and 6.7-8.3 M (2002–2007); in autumn, the cycles are 2.9-7.3 M (1979–1997), 5.3-6.8 M (1964–1970), and 2-2.6 M (1961–1963). These results indicate that SPEI has significant characteristics of periodic variations in the frequency domain at annual and summer-autumn scales. Additionally, the annual mean SOI, summer NAO, and autumn MDI also exhibit similar periodic variation characteristics (Fig. 9j, l, o).

-

(2)

In the high-frequency range (2.6-7.8 M), the resonance between MDI and SPEI in autumn is the most significant, especially during the period from 1963 to 1997 (Fig. 9p), with a negative or near-negative correlation observed between 1988 and 1999 (3-4.8 M) (Fig. 9q). However, in the low-frequency range (11.7-25.5 M, 1948–1978), the negative correlation between the two is significant but discontinuous (Fig. 9q). This suggests that MDI’s impact on meteorological drought in autumn has a certain lag effect. In contrast, the high-frequency resonance cycles between NAO and SPEI in summer are relatively weaker, but a strong near-positive correlation was observed during 1948–1957, 2004–2010, and 2020–2023 (Fig. 9m, n), indicating that NAO is a major driving factor for meteorological drought in summer. The high/low-frequency range correlations between SOI and SPEI at the annual scale have six resonance cycles, passing the 95% red noise test (Fig. 9k), with significant near-negative correlations in the high-frequency range (e.g., 2-3.1 M during 1948–1951 and 3.2-6.1 M during 2015–2023) (Fig. 9l). This suggests that SOI’s impact on meteorological drought at the annual scale also has a lag effect.

-

(3)

At the monthly scale, SPEI exhibits three significant oscillation cycles in April, September, and October (Fig. 9a, d, g), with NAO showing a weaker oscillation cycle in September (1986–1994, 2.38-3.214 M) (Fig. 9d). Nino 3.4 shows differences in positive and negative phases in April (e.g., positive phase of 3.1-4.3 M during 1969–1975, negative phase of 3.8-6.8 M during 1981–2003) (Fig. 9b), with particularly significant lag and persistence effects on meteorological drought during 1996–2000 and 2015–2023 (Fig. 9c). Overall, Nino 3.4, NAO, and MDI exhibit complex characteristics of lag and persistence in their impact on meteorological drought in specific months.

To better reflect the impact of global climate change on drought-driving mechanisms, this study conducted principal component analysis (PCA) on 10 atmospheric circulation factors, extracting principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1 to analyze their comprehensive impact (R) on meteorological drought (SPEI) (Fig. 10a-e). The results indicate that the influence of annual and seasonal atmospheric circulation principal components on meteorological drought is as follows: PC1 > PC2 > PC3 > PC4, showing differences in positive and negative effects (Fig. 10a-e), with annual mean PC1 and summer PC2 having correlation coefficients of 0.25, respectively (Fig. 10a, d). The impact of monthly-scale principal component factors (PCs) on meteorological drought is more significant, with positive influences in January and December, while the other months show alternating positive and negative effects. In April, PC4, and in May, PC2, have the greatest positive influence (0.24), and in September, PC4 has the greatest negative influence (-0.36) (Fig. 11a).

The impact of regional climate change on meteorological drought

Compared to global atmospheric circulation, regional climate change has a more significant impact on meteorological drought in Southwest China, and this impact is mainly characterized by a negative correlation (Fig. 7d). Overall, regional evapotranspiration has the most significant influence on meteorological drought, particularly in July and November (-0.303, -0.346; Sig.<0.01) as well as in January, March, and the autumn season (Sig.<0.05). This indicates that once meteorological drought occurs, the replenishment of moisture in the air mainly comes from the region’s evapotranspiration. That is, the stronger the evapotranspiration, the greater the region’s ability to regulate drought, resulting in a milder drought37 (Fig. 7d).

The next most significant factors are temperature and wind speed. Temperature has a significant positive effect on meteorological drought in January, August, and the autumn season (Sig.<0.05), while wind speed shows a significant impact in April (Sig.<0.05) and on an annual average basis (Sig.<0.01) (Fig. 7d). This suggests that higher temperatures increase the saturation temperature of the atmosphere, making it more difficult for water vapor to condense into droplets, which exacerbates drought38,39. Additionally, higher wind speeds can accelerate the loss of water vapor molecules in the air, leading to a decrease in relative humidity, thereby worsening meteorological drought.

An increase in air pressure can also suppress evapotranspiration, leading to a reduction in moisture and intensifying drought40, especially in October, where air pressure is significantly negatively correlated with SPEI (R=-0.298, Sig.<0.01). Thus, during drought periods, the impact of precipitation on SPEI is relatively weak, mainly because moisture replenishment relies on evapotranspiration. This result is similar to the findings of Ghamghami (2019)41, who found that temperature played a more significant role than precipitation in the study of drought characteristics in Iran from 1988 to 2017, suggesting that SPEI is suitable for calculating drought in Iran. This could be the result of global warming causing changes in regional precipitation and potential evapotranspiration, leading to the intensification of drought42,43.

Similarly, to explore the driving role of regional (local) climate change on drought, this study conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) on eight local climate factors, extracting principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1 to explore their correlation (R) with meteorological drought (SPEI) (Fig. 10f-j). The results show that, compared to global atmospheric circulation, regional climate composite factors (principal components) have a relatively weaker impact on meteorological drought, mainly showing a negative correlation (Fig. 10f-j). This may be due to the strong correlation between regional climate factors, which weakens the influence of principal components on drought. Although principal components have some positive impact on drought during the autumn and winter seasons, they did not pass the 0.05 significance test (Fig. 10i, j). However, the root mean square error (RMSE) and standard deviation are both greater than or equal to 1 (except in autumn), indicating that the principal components still contain substantial original climate information and can reasonably explain the mechanisms of meteorological drought. On a monthly scale, the principal components show significant variations in their positive and negative impacts on meteorological drought, with negative impacts in February, September, and October, a positive impact in November, and alternating positive and negative impacts in other months (Fig. 11b).

The wavelet analysis between global atmospheric circulation factors and SPEI (annual, seasonal, and monthly scales). Map was created with Matlab version 2014b (http://matlab.huizo.cn/).

The correlation coefficient (R) between global atmospheric circulation (a–e)/local climate (f–j) principal component factors (PCs) and SPEI (annual and seasonal scales). Map was created with Origin version 2022 (https://www.originlab.com/).

The driven of Principal components of global atmospheric circulation (a) and local climate factors (b) to SPEI, and 3-month moving average of Nino 3.4 (ONI) (c). Map was created with origin version 2022 (https://www.originlab.com/).

The mechanism by which land cover change drives meteorological drought

As previously mentioned, meteorological drought is primarily caused by a prolonged reduction in rainfall or rainfall amounts falling below a certain threshold, leading to a decrease in atmospheric water vapor and consequently resulting in water resource shortages within a watershed44,45. Under conditions of insufficient rainfall, the evapotranspiration from a watershed becomes a crucial source of replenishment for atmospheric water vapor. Human activities significantly influence the evapotranspiration rates under different land use types through the reconstruction or degradation of surface or underground resources46,47, resulting in a significant negative correlation between land use types and meteorological drought (Fig. 12a).

Figure 12a shows that the correlation (R) between land use types and the Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) in Southwest China gradually weakens from the southeast to the northwest. The proportion of areas with a significant negative correlation in the southeastern region reaches 33.14%, while the northwestern, central, and parts of the southwestern regions exhibit a positive correlation (0.13%). Overall, the average probability of land use types driving meteorological drought ranges from 0.39 to 0.42 (Fig. 12b), with construction land showing a relatively concentrated driving effect on drought (0.38–0.42), while grasslands exhibit a more dispersed driving effect (0.37–0.45). The variance in drought-driving effects is smaller for cultivated land and construction land, whereas grasslands show larger variance. Cultivated land and water bodies have a positively skewed distribution in their drought-driving effects, while grasslands and construction land display a negatively skewed distribution, and woodland is approximately normally distributed. The probability of land use types driving extreme drought is relatively low (0.01) and follows a normal distribution (except for water bodies, which show a positive skew of 0.17), while the probability of driving moderate drought is relatively higher (0.15–0.17), concentrated within the range of 0.14–0.185 (Fig. 12b). The driving effect of cultivated land on severe drought is relatively strong and dispersed (0.025–0.155), while other land use types have a weaker and more concentrated effect on severe drought (Fig. 12b). This may be because construction land primarily consists of artificially hardened surfaces with concentrated spatial distribution, which accelerates surface runoff after rainfall and reduces the infiltration rate, thereby weakening regional evapotranspiration48,49.

In contrast, grasslands and woodlands are mostly natural surfaces with more widespread spatial distribution, which helps promote surface runoff and increase rainfall infiltration rates. However, due to their ecological water needs, grasslands and woodlands also consume a certain amount of soil moisture and atmospheric water vapor, thereby influencing watershed evapotranspiration50. Compared to construction land, cultivated land has a relatively smaller impact on regional evapotranspiration due to its nature of anthropogenic disturbance and relatively concentrated distribution. Water bodies, on the other hand, account for the smallest proportion of area, and thus their ability to regulate meteorological drought is relatively weak51.

The coupled mechanism by which atmospheric circulation and land use/land cover drive meteorological drought

As analyzed in Sect "Analysis of drought mechanisms" (Fig. 2), Fig. 13 provides a comprehensive overview of the driving effects of global climate change, local climate anomalies, and land use on meteorological drought in Southwest China. The probability of drought occurrence from high to low is as follows: El Niño year (0.32–0.52) > Normal year (0.31–0.51) > La Niña year (0.27–0.5), indicating that when sea surface temperatures rise (fall), the sea-air exchange/circulation intensity increases (decreases), and the regulatory capacity of atmospheric circulation on meteorological drought in Southwest China correspondingly strengthens (weakens)52. During La Niña years, extreme local climate anomalies (Cv = 1.5) have the most substantial driving effect on meteorological drought (0.33–0.5), followed by normal climate (Cv = 1.1) and mild anomalies (Cv = 1.2) (0.275–0.445), whereas moderate anomalies (Cv = 1.3) and severe anomalies (Cv = 1.4) have the smallest driving effects (0.33–0.39) (Fig. 13a).

In normal years, extreme local climate anomalies exhibit the strongest driving effect on meteorological drought (0.51), followed by normal climate and severe anomalies (0.41–0.48), with mild and moderate anomalies having the weakest driving effects (0.32–0.43) (Fig. 13b). During El Niño years, normal and severe anomalies (0.32–0.52) have a higher driving effect on meteorological drought than extreme anomalies (0.4–0.5), while mild and moderate anomalies show relatively lower driving effects (0.36–0.48) (Fig. 13c). These results indicate that under global atmospheric circulation conditions, regional climate anomalies can significantly promote or inhibit meteorological drought in Southwest China53,54.

Regarding the coupled impacts, during La Niña years, cultivated land and grassland have the most substantial driving effects on meteorological drought under normal and mild anomalies (0.33–0.445), especially grassland under extreme anomaly conditions, reaching a driving effect of 0.5; under moderate and severe anomalies, the drought driving effects across different land types are roughly equal (0.33–0.39), while woodland stands out in terms of its driving effect on drought under normal and mild anomalies. In normal years, woodland shows the strongest drought driving effect under extreme anomaly conditions (0.51), followed by cultivated land and grassland under normal conditions, as well as woodland and grassland under severe anomaly conditions (0.43–0.485). In contrast, water bodies exhibit the weakest driving effect under mild anomalies (0.325–0.43). During El Niño years, grassland shows the strongest driving effect on drought under normal conditions (0.44–0.52), followed by grassland under extreme anomaly conditions (0.4–0.5), while water bodies have the weakest driving effect under normal conditions (0.32–0.44). These results indicate that under the dual influences of global climate change and local climate anomalies, the impact of human activities on meteorological drought cannot be ignored. Specifically, grassland and woodland have the most substantial regulatory effects on meteorological drought, followed by cultivated land, whereas construction land and water bodies have relatively weaker regulatory capacities due to their smaller distribution areas55,56.

Simultaneously, during La Niña years, woodland and grassland exhibit the greatest variance in drought driving under normal and mild anomalies, while under moderate and severe anomalies, the drought driving variance across land types is roughly equal and more concentrated. Under extreme anomalies, the drought driving effects of cultivated land, woodland, grassland, and water bodies show a normal distribution; in normal years, grassland has the largest drought driving variance under mild anomalies with a positive skew, while cultivated land and grassland have the smallest variance under severe anomalies with a negative skew, and woodland approaches a normal distribution under extreme anomalies. Similarly, during El Niño years, the variance in drought driving across land types varies complexly, showing positive and negative skewed distributions. This result demonstrates the differential impact of human activities on rainfall storage, thereby significantly influencing the regulation capacity of meteorological drought57,58,,59.

The driven of land-use types to drought. Map was created with ArcGIS version 10.3(https://www.arcgis.com/) and origin version 2022 (https://www.originlab.com/).

The coupling driven between global/local climate changes and land-use types to SPEI. Map was created with origin version 2022 (https://www.originlab.com/).

Discussion

Background and driving factors of meteorological drought

Although Southwest China is located inland, it is greatly influenced by the Southwest and Southeast monsoons60,61. This region experiences abundant rainfall, with annual precipitation ranging between 601.65 and 1701.06 mm, resulting in relatively mild meteorological drought conditions (mainly moderate drought) (Fig. 6). However, meteorological drought is not caused by a single factor but is the result of multiple interacting factors. Persistent low rainfall, abnormal temperature increases, and sharp decreases in basin evaporation are critical causes of meteorological drought7,8,45. Atmospheric water vapor is a key indicator of meteorological drought62, primarily derived from atmospheric water vapor transport and regional (basin) evapotranspiration9,12. Therefore, exploring the regulatory effects of global atmospheric circulation (10 factors) and regional (local) climate anomalies (8 factors) on meteorological drought is scientifically sound and reasonable. It also helps to deepen the understanding of the complex mechanisms of meteorological drought609,63.

Regulation of meteorological drought by global atmospheric circulation

This study deepens the understanding of how global atmospheric circulation regulates meteorological drought in Southwest China, revealing significant spatial patterns on annual and seasonal scales between 1948 and 2023: a decreasing trend from north to south on an annual, spring, and winter basis, a decreasing trend from east to west in autumn, and alternating patterns of strength from east to west in summer. Drought frequency ranges from 0.35 to 0.39, generally showing a spatial pattern that decreases from the southwest to the northeast (Fig. 5). These results indicate that global atmospheric circulation plays a significant role in regulating the spatial and temporal distribution of meteorological drought in Southwest China64,65,66,67. For instance, in September and during summer, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) is a major driver of meteorological drought, with persistence observed over 8.5-9 M (1982–1991) and 12.4–14.4 M (1980–1995), and a lag effect noted over 3.7–5.3 M (2002–2011). Additionally, the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) exhibits a lag effect on meteorological drought on an annual scale, while the Mode Dipole Index (MDI) demonstrates a pronounced lag effect on the SPEI in October and autumn. Nino 3.4 shows both lag and persistence effects in April (Fig. 9a-c). Compared to previous studies, this research, through long-term time series analysis, for the first time reveals the multi-scale impact patterns of ENSO and NAO in the southern Karst basin, enriching the existing studies on meteorological drought regulatory mechanisms.

Impact of regional climate anomalies on meteorological drought

Drought often indicates long-term rainfall deficiency in a basin (region), making local climate anomalies a key trigger of meteorological drought, particularly factors like local evapotranspiration, temperature, wind speed, and atmospheric pressure67,68. This study finds that regional (local) climate anomalies primarily have a negative correlation with meteorological drought (Fig. 7d), closely related to the role of local evapotranspiration as a source of atmospheric water vapor. Local temperature/dew point directly affects the water vapor capacity of the atmosphere, while wind speed/pressure modulates the atmospheric water-holding capacity69. Unlike previous studies, this research clarifies the negative feedback mechanism of regional climate anomalies on meteorological drought in the unique ecological system of the Karst basin through multi-factor analysis, providing new scientific evidence for understanding the regional characteristics of meteorological drought. Therefore, focusing solely on global atmospheric circulation or local climate anomalies is incomplete; a systematic study that combines both is needed70,71.

Impact and regulation of human activities on meteorological drought

Human activities significantly influence the water storage capacity of basins (regions) through interference with surface and underground environments, altering the occurrence patterns of meteorological drought by suppressing evapotranspiration72,73,74. The study results indicate a significant negative correlation between human activities and meteorological drought (SPEI) in southeastern China, with the negatively correlated area accounting for 33.14%, while some regions (northwest, central, and southwest) show a positive correlation (0.13%) (Fig. 12a). These results further demonstrate that human activities have a significant regulatory effect on local climate anomalies and meteorological drought through their impact on surface hydrological cycles. Thus, exploring the influence of human activities on meteorological drought from the perspective of global climate change, combined with regional (local) climate anomalies, has important scientific significance.

Variations in drought drivers across different years and land use types

The formation of meteorological drought results from the combined action of various factors, with significant differences in the contribution of each factor to drought drivers5,74,75,76,77. This study shows that, in different climatic years, the probability of global climate change driving drought varies significantly: El Niño years (0.32–0.52) > Normal years (0.31–0.51) > La Niña years (0.27–0.5) (Fig. 13). During La Niña and normal years, extreme local climate anomalies (Cv = 1.5) have the greatest driving effect on meteorological drought (0.33–0.51), while in El Niño years, the driving effect of normal and strong anomalies is higher than that of extreme anomalies (Fig. 13a-c). These results indicate that under different global atmospheric circulation backgrounds, local climate anomalies play a significant role in meteorological drought in Southwest China77,78. This study, for the first time, reveals the differences in drought drivers under various climate backgrounds for specific land use types (e.g., grassland, woodland), providing a more detailed perspective for studying meteorological drought.

Limitations and future perspectives

Due to data limitations, this study only uses monthly meteorological data (with spatial resolutions of 0.1° and 0.25°) to calculate the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), which somewhat limits the spatial and temporal accuracy of the results. Future studies will consider higher spatial and temporal resolution meteorological data (e.g., hourly, daily, 0.01° resolution) and select multiple meteorological drought indices (e.g., PDSI, SPI, SPEI) for comparative analysis, aiming to enhance the representativeness and generality of the research results. This will more comprehensively reveal the mechanisms of meteorological drought in Southwest China.

Conclusion

To reveal the mechanisms driving meteorological drought in Southwest China, this study calculated the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) and the Hurst index based on monthly meteorological data, and explored the influence of global (regional) climate change coupled with human activities on meteorological drought using Bayesian principles. The following three conclusions were drawn:

-

(1)

Between 1948 and 2023, the annual and seasonal meteorological drought in Southwest China mainly exhibited a spatial distribution trend characterized by a north-south gradient (annual average, spring, and winter) or an east-west decrease (autumn). In summer, the distribution showed alternating east-west variations in intensity. This spatial pattern closely aligns with the spatial characteristics of temperature and evaporation. Among the drought recurrence periods, extreme drought had the longest duration (113.5 months in spring to 76.95 months annually), while moderate drought had the shortest duration (32.59 months in summer to 20.88 months in winter). On a monthly scale, there was a significant increase in drought after 1995, especially in the frequency of moderate and above-moderate droughts. This result indicates that drought in Southwest China has intensified over the years, with climate change driving more frequent and prolonged drought events.

-

(2)

Global atmospheric circulation significantly influences meteorological drought in Southwest China. Factors such as Nino 3.4, SOI, AMO, MDI, MEI, and NAO exhibit persistence and lagged effects on drought across different frequency domains. For example, SOI has a more pronounced impact on annual and summer-autumn scales, while NAO plays a stronger role during summer (Sig. < 0.05). Compared to global atmospheric circulation, regional climate change exerts a stronger regulatory effect on meteorological drought, particularly through evapotranspiration, which has a negative impact on drought during July and November (Sig. < 0.01), and January and March (Sig. < 0.05). This highlights the importance of evapotranspiration in supplying atmospheric moisture during drought periods; higher evapotranspiration is associated with lower drought intensity. Temperature and wind speed, on the other hand, have a positive effect on meteorological drought, especially temperature in January and August, and wind speed in April (Sig. < 0.05) and annually (Sig. < 0.01). Therefore, drought management should emphasize the regulation of regional evapotranspiration and temperature to mitigate the impacts of meteorological drought.

-

(3)

Land use change has shown a significant negative correlation with meteorological drought in Southwest China, with a driving probability of 0.39–0.42. During different climate anomaly years, the coupled effect of land use and climate change on meteorological drought varies significantly: during El Niño years, land use types have the highest driving effect on drought (0.32–0.52), while La Niña years show a higher influence of localized climate anomalies on drought regulation (0.33–0.5). Among different land types, the impact of construction land on drought is more concentrated (0.38–0.42), while the influence of grasslands is more dispersed (0.37–0.45). During La Niña years, grasslands have a driving effect of up to 0.5 under extreme anomaly conditions, while in normal years, woodlands exert a stronger driving effect under extreme conditions (0.51). These findings indicate that human activities, through changes in land cover types, significantly affect regional evapotranspiration and water vapor cycles, playing a role in either promoting or mitigating meteorological drought.

Based on the findings of this study, it is recommended that future drought prevention and control efforts adjust land use strategies in response to different climate conditions (such as El Niño and La Niña years), optimizing the layout of grasslands, woodlands, and construction land to enhance regional capacity to regulate meteorological drought. Additionally, management should focus on addressing the risk of drought intensification due to regional temperature increases, by increasing vegetation cover or improving irrigation methods, to enhance the region’s resilience to the adverse effects of climate change.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

25 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08972-6

References

Zhang, Y. et al. Impact of climate change on drought patterns: A case study in Southwest China. Environ. Res. Lett. 17 (3), 045004 (2022).

Jha, R., Singh, S. P. & Choudhary, M. Drought impacts on agricultural production and adaptation strategies. Agric. Econ. Res. 14 (2), 134–150 (2019).

Su, B. et al. Drought losses in China might double between the 1.5°C and 2.0°C warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, 10600–10605 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. Dynamics and attributions of baseflow in the semiarid loess plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. (2019).

Li, F. et al. Influence of irrigation and groundwater on the propagation of meteorological drought to agricultural drought. Agric. Water Manag. 277, 108099 (2023).

American Meteorological Society (AMS). Meteorological drought-policy statement. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 78, 847–849 (1997).

Asadi Zarch, M. A., Sivakumar, B. & Sharma, A. Droughts in a warming climate: A global assessment of standardized precipitation index (SPI) and reconnaissance drought index (RDI). J. Hydrol. 526, 183–195 (2015).

Ding, Y., Xu, J. & Wang, X. Propagation of meteorological to hydrological drought for different climate regions in China. J. Environ. Manag. 283, 111980 (2021).

Li, R. et al. Quantitative analysis of agricultural drought propagation process in the Yangtze river basin by using cross wavelet analysis and Spatial autocorrelation. Agric. Meteorol. 280. (2020).

Wu, H. et al. Agricultural drought prediction based on conditional distributions of vine copulas. Water Resour. Res. 57, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR029562 (2021).

Peters-Lidard, C. D., Mocko, D. M. & Su, L. Advances in land surface models and indicators for drought monitoring and prediction. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 102 (2021).

Gimeno, L. et al. Oceanic and terrestrial sources of continental precipitation. Rev. Geophys. 50(4) (2012).

Gao, T., Wang, H. & Zhou, T. Changes of extreme precipitation and nonlinear influence of climate variables over the monsoon region in China. Atmos. Res. 197, 379–389 (2017).

Gao, T. et al. Combined impacts of climate variability modes on seasonal precipitation extremes over China. Water Resour. Manag. 36, 2411–2431 (2022).

Awange, J. L. et al. Water storage changes and climate variability within the nile basin between 2002 and 2011. Adv. Water Resour. 73, 1–15 (2014).

Xiao, M., Zhang, Q. & Singh, V. P. Influences of ENSO, NAO, IOD, and PDO on seasonal precipitation regimes in the Yangtze river basin, China. Int. J. Climatol. 35, 3556–3567 (2015).

Wang, F., Lai, H. & Li, Y. Dynamic variation of meteorological drought and its relationships with agricultural drought across China. Agric. Water Manag. 261, 107301 (2022).

Li, J., Zhang, Q., Xu, F. & Li, S. Impact of karst topography on hydrological processes in Drought-Prone regions. J. Hydrol. 590, 125344 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Li, H., Chen, X. & Wang, J. Land use changes and their impact on drought frequency and intensity in Southern China. Environ. Res. Lett. 14 (9), 094001 (2019).

Zhang, B. & He, C. A modified water demand Estimation method for drought identification over arid and semi-arid regions. Agric. Meteorol. 230–231, 58–66 (2016).

Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of land-use scenarios for the period 1500–2100: 600 years of global gridded annual land-use transitions, wood harvest, and resulting secondary lands. Clim. Change. (109), 117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0153-2 (2011).

Wang, L., Li, Z., Xu, B. & Sun, F. Urbanization and Groundwater Depletion: the Influence of Impervious Surfaces on Regional Drought Risk Environ. Sci. Technol. 12, 557551–7560. (2012).

Liu, X., Zhang, Q., Chen, L. & Zhao, F. Agricultural expansion and soil degradation in karst regions of Southern China. Land. Use Policy. 70, 14–22 (2018).

Xu, J., Li, S., Zhang, Y. & Li, H. Effects of land cover change on hydrological cycle in karst regions of China. Earth. Surf. Proc. Land. 47 (4), 947–957 (2022).

Qi, Z. et al. Human activities impact the propagation from meteorological to hydrological drought in the yellow river basin, China. J. Hydrol. 623, 129752 (2023).

McKee, T. B., Nolan, J. & Kleist, J. The Relationship of Drought Frequency and Duration To time Scales (Preprints, Eighth Conf on Appl Climatol., 1993).

Chen, H. & Sun, J. Changes in drought characteristics over China using the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 28, 5430–5447 (2015).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Beguería, S. & López-Moreno, J. I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 23, 1696–1718 (2010).

Zeng, P. et al. Future river basin health assessment through reliability-resilience-vulnerability: thresholds of multiple dryness conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 741, 140395 (2020).

Guo, H. et al. Spatial and Temporal characteristics of droughts in central Asia during 1966–2015. Sci. Total Environ. 624, 1523–1538 (2018).

Oloruntade, A. J. et al. Analysis of meteorological and hydrological droughts in the Niger-South basin, Nigeria. Glob Planet. Chang. 155, 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2017.05.002 (2017).

Labat, D. Recent advances in wavelet analyses: part 1. A review of concepts. J. Hydrol. 314, 275–288 (2005).

Rehana, S. & Naidu, G. S. Development of hydro-meteorological drought index under climate change—Semi-arid river basin of Peninsular India. J. Hydrol. 594, 125973 (2021).

WMO. Standardized Precipitation Index User Guide (World Meteorological Organization, 2012).

Liu, C. et al. Spatiotemporal drought analysis by the standardized precipitation index (SPI) and standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) in Sichuan Province, China. Sci. Rep. 11, 1280 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Projected changes in climate extremes over China in the 21st century from a high-resolution regional climate model (RegCM3). Chin. Sci. Bull. 58, 1443–1452 (2012).

Asif, Z. et al. Climate Change Impacts on Water Resources and Sustainable Water Management Strategies in North America. Water Resour. Manag. 1–16. (2023).

Gohain, K. J., Mohammad, P. & Goswami, A. Assessing the impact of land use land cover changes on land surface temperature over Pune City, India. Quatern Int. 575–576, 259–269 (2021).

Dankers, R., Arnell, N. W. & Clark, D. B. First look at changes in flood hazard in the inter-sectoral impact model intercomparison project ensemble. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 3257–3261 (2014).

Kheyruri, Y., Nikaein, E. & Sharafati, A. Spatial monitoring of meteorological drought characteristics based on the NASA POWER precipitation product over various regions of Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-25283-3 (2023).

Ghamghami, M. & Irannejad, P. An analysis of droughts in Iran during 1988–2017. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/S42452-019-1258-X/TABLES/5 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Enhancing soil drought induced by climate change and agricultural practices: observational and experimental evidence from the semiarid area of Northern China. Agric. Meteorol. 243, 74–83 (2017).

Piao, S. et al. The impacts of climate change on water resources and agriculture in China. Nature 467, 43–51 (2010).

Carrao, H. et al. An optimized system for the classification of meteorological drought intensity with applications in drought frequency analysis. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 53 (8), 1943–1960. https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-13-0167.1 (2014).

Li, Q., Sheng, B. & Huang, J. Different climate response persistence causes warming trend unevenness at continental scales. Nat. Clim. Change. 12, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01313-9 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. Effects of forest structure on hydrological processes in China. J. Hydrol. 561, 187–199 (2018).

Mahmon, N. A., Ya’acob, N. & Yusof, A. L. Differences of image classification techniques for land use and land cover classification. In: 2015 IEEE 11th International Colloquium on Signal Processing & its Applications (CSPA). IEEE, 90–94. (2015).

Cao, Y. & Sen Roy, S. Spatial patterns of seasonal level trends of groundwater in India during 2002–2016. Weather 75 (4), 123–128 (2020).

Minnig, M., Moeck, C., Radny, D. & Schirmer, M. Impact of urbanization on groundwater recharge rates in Dübendorf, Switzerland. J. Hydrol. 563, 1135–1146 (2018).

Islam, A. R. M. T. et al. Sustainable groundwater quality in Southeast coastal Bangladesh: co-dispersions, sources, and probabilistic health risk assessment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 18394–18423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01447-4 (2021).

Baker, T. J. & Miller, S. N. Using the soil and water assessment tool (SWAT) to assess land use impact on water resources in an East African watershed. J. Hydrol. 486, 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2013.01.041 (2013).

Seager, R. & Hoerling, M. Atmosphere and ocean origins of North American droughts. J. Clim. 27, 4581–4606 (2014).

Afzal, M. & Ragab, R. Impact of the future climate and land use changes on the hydrology and water resources in South East England, UK. Am. J. Water Resour. 20, 218–231 (2020).

Torabi Haghighi, A., Darabi, H. & Shahedi, K. A scenario-based approach for assessing the hydrological impacts of land use and climate change in the Marboreh watershed, Iran. Environ. Model. Assess. 25, 41–57 (2020).

Li, Q., He, P. & He, Y. Investigation to the relation between meteorological drought and hydrological drought in the upper Shaying river basin using wavelet analysis. Atmos. Res. 234, 104743 (2020).

Ma, F., Luo, L. & Ye, A. Drought characteristics and propagation in the semiarid Heihe river basin in Northwestern China. J. Hydrometeorol. 20, 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-18-0129.1 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Guan, D. & Jin, C. Analysis of impacts of climate variability and human activity on streamflow for a river basin in Northeast China. J. Hydrol. 410, 239–247 (2011).

Nyatuame, M., Amekudzi, L. K. & Agodzo, S. K. Assessing the land use/land cover and climate change impact on water balance on Tordzie watershed. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 20, 100381 (2020).

Ahmadi-Sani, N., Razaghnia, L. & Pukkala, T. Effect of Land-Use change on runoff in hyrcania. Land 11, 220 (2022).

Chen, Y. & Zhai, P. M. Persistent extreme precipitation events in China during 1951–2010. Clim. Res. 57, 143–155 (2013).

Zhang, L. et al. Variability of winter extreme precipitation in Southeast China: contributions of SST anomalies. Clim. Dyn. 45, 2557–2570 (2015).

Srivastava, A., Kumari, N. & Maza, M. Hydrological response to agricultural land use heterogeneity using variable infiltration capacity model. Water Resour. Manag. 34, 3779–3794 (2020).

Yu, L., Leng, G. & Python, A. A comprehensive validation for GPM IMERG precipitation products to detect extremes and drought over Mainland China. Weather Clim. Extrem. 36, 100458 (2022).

Tian, L., Leasor, Z. & Quiring, S. M. Potential to improve precipitation forecasts in Texas through the incorporation of multiple teleconnections. Int. J. Clim. 37 (10), 3863–3872 (2017).

Guirguis, K., Gershunov, A. & Cayan, D. R. Interannual variability in associations between seasonal climate, weather, and extremes: wintertime temperature over the Southwestern united States. Environ. Res. Lett. 10 (12), 124023 (2015).

Dore, M. H. I. Climate change and changes in global precipitation patterns: what do we know? Environ. Int. 31 (8), 1167–1181 (2005).

Knight, J. R., Folland, C. K. & Scaife, A. A. Climate impacts of the Atlantic multidecadal Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33 (17). https://doi.org/10.1029/2006gl026242 (2006).

Das, J., Jha, S. & Goyal, M. K. Non-stationary and copula-based approach to assess the drought characteristics encompassing climate indices over the Himalayan States in India. J. Hydrol. 580, 124356 (2020).

Wen, Q. H., Zhang, X. & Xu, Y. Detecting human influence on extreme temperatures in China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1171–1176 (2013).

Maleski, J. J. & Martinez, C. J. Coupled impacts of ENSO AMO and PDO on temperature and precipitation in the Alabama–Coosa–Tallapoosa and Apalachicola–Chattahoochee–Flint river basins. Int. J. Climatol. 38, 717–728 (2018).

Shi, P. et al. How do the multiple large scale climate oscillations trigger extreme precipitation? Glob Planet. Change. 157, 48–58 (2017).

Li, W., Li, L. & Chen L.Impacts of land use and land cover change and reforestation on summer rainfall in the Yangtze river basin.hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 4531–4548. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-4531-2021 (2021).

Tahiru, A. A., Doke, D. A. & Baatuuwie, B. N. Effect of land use and land cover changes on water quality in the Nawuni catchment of the white Volta basin, Northern region, Ghana. Appl. Water Sci. 10, 198 (2020).

Chiang, F., Mazdiyasni, O. & AghaKouchak, A. Evidence of anthropogenic impacts on global drought frequency, duration, and intensity. Nat. Commun. 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22314-w (2021).

Sun, G., McNulty, S. G. & Lu, J. Regional Annual Water Yield from Forest Lands and its Response To Potential Deforestation across the Southeastern United States Hydrology. 308258–268 (2005).

Sun, G. et al. Potential water yield reduction due to forestation across China. Hydrology 328, 548–558 (2006).

Yan, S. et al. The complex drought effects associated with the regulation of water-use efficiency in a temperate water-limited basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2021.100864 (2021).

Yang, Y. T. et al. Comparing Palmer drought severity index drought assessments using the traditional offline approach with direct climate model outputs. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24 (6), 2921–2930 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Editors and anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions and comments. This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou Province, China (QKHJ-ZK[2023] Key028); Natural and scientific research fund of Guizhou Water Resources Department (KT202237); the Natural Science Foundation of China (u1612441; 41471032); Natural and scientific fund of Guizhou Science and Technology Agency (QKH J [2010] No. 2026, QKH J [2013] No. 2208); 2015 Doctor Scientific Research Startup Project of Guizhou Normal University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H. wrote the main manuscript text. X.L. and M.Q. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 and participated in the revision of the paper. M.J. prepared Table 1 and collected of data. All authors reviewed the manuscript. We are very grateful to all contributors to this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in Figure 2, where a guiding dashed line from “Global meteorological data” to “ONI” was missing and the abbreviation “Woo_L” was missing the letter “L” at the end.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Z., Gu, X., Wang, M. et al. The coupled effect of climate change and LUCC on meteorological drought in a karst drainage basin, Southwest China. Sci Rep 15, 9134 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93035-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93035-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Climate–human interactions influence widespread peatland subsidence and soil carbon stock vulnerability in China

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Spatiotemporal evolution and driving mechanisms of compound dry and hot events in the Yellow River Basin under climate warming

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2025)