Abstract

This study examines the relationship between Big Five personality traits and aggression in physical education students, with particular attention to gender differences in aggressive behaviors. A cross-sectional study was conducted using a convenience sampling method to recruit physical education undergraduates aged 18–24. an online questionnaire was distributed via WeChat groups, yielding 410 valid responses (94% effective response rate) from students in Henan, China (245 males, 165 females). Participants completed the Big Five Personality Short Form Scale and the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ). Statistical analyses, including Pearson correlation, one-way ANOVA, and hierarchical regression models, were performed to examine the relationship between personality traits and various types of aggression, as well as to explore gender-specific patterns. Gender differences were found in the types of aggression exhibited by male and female students. Male students showed significantly higher levels of physical aggression (mean = 1.82, SD = 0.66) compared to female students (mean = 1.57, SD = 0.53), with a significant difference (t = 4.254, p < 0.001). Conversely, female students scored significantly higher in anger (mean = 2.15, SD = 0.75) than male students (mean = 1.97, SD = 0.74), with a significant difference (t = − 2.423, p < 0.01). In terms of personality traits, neuroticism was positively associated with general aggression, anger, and hostility, supporting previous research that links emotional instability with aggressive behavior. Agreeableness was negatively correlated with physical aggression, and conscientiousness was linked to lower levels of verbal aggression. Notably, individuals with high extraversion and low conscientiousness exhibited the highest tendency for verbal aggression, highlighting the synergistic effects of personality trait combinations. Together, these personality traits explained 12.2% of the variance in aggression, emphasizing the significant role of personality in predicting aggression in physical education contexts. These findings suggest that both personality traits and gender contribute to aggressive behaviors. Specifically, male students with lower agreeableness are more likely to exhibit physical aggression, while female students with higher neuroticism tend to exhibit more anger. The “high extraversion-low conscientiousness” trait combination emerged as a key predictor of verbal aggression, underscoring the importance of addressing personality trait interactions in intervention design.Interventions aimed at improving emotional regulation, agreeableness, and conscientiousness could be particularly effective in reducing aggression. Tailoring strategies to address gender differences in aggression could further enhance the effectiveness of these interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aggression, defined as a multidimensional construct encompassing physical aggression (overt bodily harm), verbal aggression (injurious language), anger (emotional arousal preceding aggression), and hostility (negative cognitive attitudes toward others), poses significant challenges in both educational and sports contexts1. These forms of aggression can disrupt the learning environment, harm interpersonal relationships, and negatively impact the overall well-being of students. Understanding the psychological basis of aggression is particularly relevant for physical education (PE) students, who often experience environments that promote competition and physical exertion. Such environments can exacerbate aggressive tendencies, especially among individuals with specific personality traits2,3.

The Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality—also known as the Big Five personality traits—provides a valuable framework for understanding the individual differences that contribute to aggression. These traits include extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness4. Neuroticism is characterized by emotional instability and a propensity toward negative emotions, which can increase susceptibility to aggressive reactions under stress5,6. On the other hand, agreeableness and conscientiousness are generally associated with empathy, prosocial behavior, and self-control, which may mitigate aggressive tendencies7,8. Extraversion and openness, while less directly linked to aggression, may influence how individuals respond to social and environmental stimuli, potentially moderating aggressive behaviors9.

The General Aggression Model (GAM) further elucidates how personality traits (e.g., neuroticism) interact with situational triggers (e.g., competition) to predict specific aggression dimensions10. For instance, neuroticism may heighten anger and hostility through emotional instability, while agreeableness and conscientiousness may suppress physical and verbal aggression via empathy and self-control.These interactions are particularly relevant in the context of physical education, where competitive dynamics and physical challenges may act as situational triggers for aggression.

Previous research has shown that neuroticism is a key predictor of aggression, especially in stressful or provoking situations, while agreeableness and conscientiousness generally mitigate aggressive tendencies11,12. However, the existing literature has largely focused on general or clinical populations, with limited research on physical education students, whose specific context may exacerbate or modulate these relationships. Moreover, gender differences in aggression expression—such as the tendency for males to exhibit more physical aggression and females to engage in relational aggression—have not been adequately explored in relation to personality traits in PE settings13. Understanding these gender-specific patterns is critical for developing targeted interventions to reduce aggression and promote positive behaviors in educational environments.

Based on the theoretical frameworks and previous research, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1

Neuroticism will positively predict all aggression dimensions (physical/verbal aggression, anger, hostility).

Rationale: Neuroticism’s link to emotional instability5 aligns with GAM’s emphasis on trait vulnerability10.

H2

Agreeableness will negatively predict physical/verbal aggression.

Rationale: Agreeableness fosters prosocial behavior, reducing overt aggression7.

H3

Conscientiousness will negatively predict verbal aggression/hostility.

Rationale: Self-regulation associated with conscientiousness mitigates indirect aggression12.

H4

Gender will moderate these relationships:

Males high in neuroticism will exhibit stronger physical aggression.

Rationale: Evolutionary pressures favor male externalization of stress2.

Females high in neuroticism will show heightened anger/hostility.

Rationale: Sociocultural norms promote female internalization of emotions13.

The present study aims to explore the relationships between the Big Five personality traits and different forms of aggression—physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility—among PE students, with an emphasis on gender-specific patterns. By exploring these relationships, the study seeks to contribute to a nuanced understanding of how intrinsic personality traits and gender interact to shape aggression in the context of physical education. The findings of this research could inform the development of targeted interventions to reduce aggression and promote positive behaviors among PE students.

Methods

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Kinetic Science Experiment Ethics Committee at Beijing Sport University. All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed of the study’s objectives, assured of the confidentiality of their responses, and advised of their right to withdraw at any point. Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants prior to data collection.

Study design

A cross-sectional design was employed to explore the relationship between Big Five personality traits and aggression among physical education (PE) students, specifically examining gender differences. Data were collected over a four-week period in March 2023 from the School of Physical Education at Anyang Normal University, located in Henan Province, China.The school was selected due to its robust PE program and diverse student population, providing a preliminary but relevant snapshot of aggression-related behaviors in this cohort.

Participants

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit PE undergraduates enrolled in relevant courses (e.g., kinesiology, sports psychology). An online questionnaire link was distributed through WeChat groups, inviting participation from approximately 500 eligible students. A total of 436 responses were received, of which 410 were retained after excluding those completed in under three minutes or containing inconsistent (patterned) answers, yielding a 94% effective response rate. Among the participants,Ages ranged from 18 to 24 years, 245 were male (59.8%), and 165 were female (40.2%).The distribution by academic year was as follows: Freshmen comprised 20.2%, Sophomores 34.6%, Juniors 15.8%, and Seniors 20.2%.Participants who self-reported psychiatric disorders or previous enrollment in aggression-focused interventions within the past year were excluded. All participants provided informed consent and were informed their involvement was voluntary.

A post-hoc power analysis using G*Power 3.114 indicated 99% power to detect medium effects (f2 = 0.15) in regression models with 5 predictors at α = 0.05, exceeding the recommended 80% threshold.

Instruments

The Chinese adjectives scale of Big-Five factor personality short scale version(BFFP-CAS-S).

BFFP-CAS-S was developed by Luo and Dai (2018), to assess the five major personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness15. The scale consists of 20 items, each presented as a bipolar adjective pair (e.g., “extroverted-introverted”), rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = completely aligned with the positive adjective, 6 = completely aligned with the negative adjective). The scoring method involves summing the scores of the items corresponding to each dimension, with reverse scoring applied to negatively worded items (items 4, 9, 14, and 19). For reverse scoring, the original score is transformed as follows: 1 → 6, 2 → 5, 3 → 4, 4 → 3, 5 → 2, 6 → 1. Higher scores indicate stronger alignment with the respective personality trait.

The scale demonstrates good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α coefficients for the dimensions was as follows: extraversion (α = 0.814), agreeableness (α = 0.744), conscientiousness (α = 0.768), neuroticism (α = 0.782), and openness (α = 0.777), with an overall reliability of α = 0.929.The BFFP-CAS-S is widely applicable to Chinese adolescents and adults, particularly in educational, psychological, and sociological research contexts.

Buss-Perry aggression questionnaire (BPAQ)

The Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ), originally developed by Buss and Perry1, is a widely used self-report measure designed to assess individual differences in aggression. The Chinese version of the BPAQ, revised by Fang Chengzhou (2016), was adapted to better suit the cultural and linguistic context of Chinese college students16. The revised version consists of 25 items, with 7 items measuring Physical Aggression, 4 items for Verbal Aggression, 6 items for Anger, and 8 items for Hostility. The scale employs a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The subscales’ internal consistencies were as follows: physical aggression (α = 0.813), verbal aggression (α = 0.744), anger (α = 0.837), and hostility (α = 0.834), with an overall reliability of α = 0.922. The Chinese BPAQ is a reliable and valid tool for assessing aggression in Chinese populations, particularly among college students.

Procedure

Recruitment: Faculty members distributed an ethics-approved study invitation via class WeChat groups. Students interested in participating accessed the survey link, which led them to a webpage containing all study-related instructions and consent procedures.

Survey Administration: The survey, administered via Wenjuanxing (a secure and widely-used Chinese survey platform), included demographic questions (e.g.,gender, academic year) followed by standardized psychological measures. Participants could only proceed after confirming their consent.

Completion Time and Integrity Checks: Response times were automatically recorded by the platform. Submissions completed in under three minutes were flagged and subsequently excluded. Pattern analysis was performed to identify straight-line or otherwise invalid responses.

Confidentiality and Incentives: responses were anonymized, and IP addresses were not recorded. No personal identifiers were collected. Participants received a post-completion lottery (100% chance of winning 1-5CNY) to maintain motivation without coercive effects.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 23.0. The following analyses were conducted:

Pearson correlation was used to examine the relationships between the Big Five personality traits and types of aggression.

Independent t-tests and One-way ANOVA were employed to explore differences in aggression across demographic variables.

Hierarchical Regression analysis assessed the predictive capacity of the Big Five traits on aggression.

Results

Common method bias test

To account for possible bias introduced by the use of self-reported questionnaires, Harman’s single-factor test was performed. Results showed a KMO value of 0.924, with eight factors having eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining 58.53% of the total variance. The first factor accounted for only 26.44%, below the 40% threshold, indicateing no significant common method bias in this study.

Gender and grade differences in aggression

Analysis of aggression across gender and academic year was conducted using independent t-tests and one-way ANOVA, respectively. Table 1 presents these findings.

Gender Differences: Male students scored higher in physical aggression (mean = 1.82, SD = 0.66) compared to female students (mean = 1.57, SD = 0.53), with a significant difference (t = 4.254, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.42, medium effect size). Conversely, female students scored higher in anger (mean = 2.15, SD = 0.75) than male students (mean = 1.97, SD = 0.74), with significant differences (t = − 2.423, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.24, small effect size).No significant gender differences were observed for verbal aggression (t = − 0.934, p = 0.351) or hostility (t = − 1.489, p = 0.137).

Grade Differences: Freshmen reported lower scores in verbal aggression, anger, and hostility compared to seniors, with significant differences found for verbal aggression (F = 3.035F, p < 0.05), anger (F = 5.213, p < 0.01), and hostility (F = 5.992, p < 0.001).

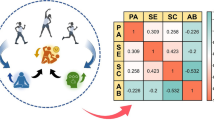

Correlation analysis between big five traits and aggression

A Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationships between the Big Five traits and various forms of aggression. Table 2 provides a summary.

Neuroticism showed positive correlations with all aggression types, including physical aggression (r = 0.191, p < 0.01), verbal aggression (r = 0.268, p < 0.01, anger (r = 0.300, p < 0.01), and hostility (r = 0.335, p < 0.01).

Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness were negatively correlated with aggression, indicating that students higher in these traits displayed lower aggression levels.

Regression analysis

To further explore whether the five factors of the Big Five personality traits directly predict aggressive behavior, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted. In the first step, gender was controlled for as a variable, and in the second step, the five dimensions of the Big Five personality traits were entered into the model. The analysis results are presented in Table 3.

Based on the data presented in Table 3, the Big Five personality traits significantly predicted aggressive behavior tendencies among physical education students. Specifically:

Physical Aggression: F = 8.068, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.068.

Verbal Aggression: F = 11.297, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.116.

Anger: F = 10.296, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.094.

Hostility: F = 11.428, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.111.

Total Aggression Score: F = 11.731, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.122.

The results indicate that gender did not significantly predict overall aggressive behavior; however, it did have a significant predictive effect on physical aggression and anger (β = − 0.144, 0.108, respectively). After controlling for gender, neuroticism emerged as a significant positive predictor of aggression (β = 0.245), anger (β = 0.258), and hostility (β = 0.271). Agreeableness significantly negatively predicted physical aggression (β = − 0.240), conscientiousness (β = − 0.169, p < 0.01) and extraversion (β = 0.204, p < 0.001) both have significant predictive effects on verbal aggression. It is worth noting that although extraversion showed a weak negative correlation with verbal aggression in the correlation analysis (r = − 0.122, p < 0.01), its regression coefficient turned positive after controlling for gender. Overall, the Big Five personality traits explained 12.2% of the variance in aggression.

Discussion

The findings reveal that neuroticism is a significant predictor of anger and hostility among PE students, particularly. This is consistent with earlier studies highlighting neuroticism’s role in heightened emotional reactivity5,6. The positive relationship between neuroticism and aggression indicates that individuals with high levels of neuroticism may benefit from interventions focused on emotion regulation skills, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), to mitigate aggressive tendencies. Furthermore, interventions that focus on mindfulness and emotional intelligence could also be effective in helping students better manage their emotions and reduce aggressive outbursts17.

The negative association between agreeableness and physical aggression aligns with previous literature, which shows that agreeable individuals are less likely to engage in aggressive behaviors due to their empathy and prosocial orientation7. This indicates that promoting empathy and prosocial behaviors through group activities and cooperative learning could be beneficial in reducing aggression, particularly among male students who are statistically more inclined toward engage in physical forms of aggression2,13.

Individuals characterized by high levels of extraversion and low levels of conscientiousness demonstrate a pronounced propensity for verbal aggression. This phenomenon is consistent with trait activation theory18, which suggests that environments rich in social interactions, such as team sports, enhance extroverts’ exposure to conflict-inducing situations. Concurrently, low conscientiousness impairs goal-directed self-regulation, including impulse control19. The dual-system model of self-control20 provides further insight into this mechanism: extroverts’ sustained involvement in high-pressure social contexts, such as competing for team positions, leads to chronic interpersonal stress. Low conscientiousness predisposes individuals to prioritize immediate emotional impulses over long-term considerations, thereby transforming stress into verbal aggression. These findings expand upon the General Aggression Model10 by illustrating that specific trait combinations, namely extraversion and conscientiousness, synergistically predict aggression through distinct pathways. Specifically, Extraversion has been shown to elevate the frequency of social interactions (opportunity pathway), whereas low conscientiousness reduces inhibitory thresholds (execution pathway), as demonstrated in sports psychology research on trait-behavior interactions21. Therefore, it is imperative for educators and coaches to prioritize interventions aimed at students exhibiting this high-risk trait profile. Such interventions may include cognitive-behavioral training to improve anticipation of consequences7 and the implementation of structured conflict-resolution protocols within team environments22.

Gender differences observed in this study indicate that males are statistically more inclined toward express aggression through physical means, whereas females are statistically more inclined toward internalize their aggression as anger. These findings are consistent with both evolutionary and sociocultural theories of aggression2,23. Evolutionary theories indicate that physical aggression in males may have developed as a means of competition for resources or mates, whereas females may have evolved to use less direct forms of aggression to avoid physical harm 2. Sociocultural theories, on the other hand, emphasize the role of gender socialization in shaping aggressive behaviors, with males being encouraged to display dominance and assertiveness, while females are often socialized to value relationships and emotional sensitivity13.

Moreover, the findings from Jiang et al. highlight the role of envy, particularly malicious envy, in mediating the relationship between neuroticism and aggression24. This indicates that emotional responses such as envy may act as a mechanism through which personality traits influence aggressive behaviors. Interventions targeting envy and promoting emotional regulation may, therefore, be effective in mitigating aggression, particularly in individuals high in neuroticism.

Implications for interventions

The study’s findings have important implications for developing targeted interventions to reduce aggression in PE settings. For students high in neuroticism, interventions focusing on emotional regulation and stress management could be particularly beneficial. Programs that promote empathy and cooperation may enhance agreeableness and reduce physical aggression in male students. Furthermore, incorporating emotional intelligence training into physical education curricula could help reduce anger-related aggression in female students, ultimately fostering a more positive and inclusive educational environment17,25.

Additionally, the findings highlight that individuals with high extraversion and low conscientiousness exhibit the highest tendency for verbal aggression. This suggests that interventions targeting this specific personality combination should focus on enhancing self-regulation and impulse control. For example, cognitive-behavioral strategies that teach students to pause and reflect before responding in conflict situations could help mitigate verbal aggression. Furthermore, structured team-building activities that emphasize conflict resolution and communication skills may reduce the likelihood of interpersonal tensions escalating into verbal aggression.

Despite these practical implications, the generalizability of the findings is constrained due to the relatively homogeneous sample, which was drawn from a single cultural and educational context. Cultural norms and values, particularly in collectivist societies, may shape how aggression is expressed and managed. For example, collectivist cultures often emphasize group harmony, which may suppress overt aggression while amplifying indirect forms such as hostility. To address these limitations, future research should adopt a cross-cultural approach, incorporating diverse cultural and educational settings to validate the findings and ensure their applicability across different populations. Expanding the scope of research to include participants from both individualistic and collectivist societies would enhance the robustness of the evidence and provide a more comprehensive foundation for intervention design.

Limitations and future research

This study is not without limitations. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causality between personality traits and aggression. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the developmental trajectories of personality traits and aggressive behavior. Additionally, the reliance on self-report measures may introduce bias, as participants may underreport aggressive behaviors due to social desirability. Future research should incorporate observational methods and multi-informant reports to provide a more comprehensive assessment of aggression.

Another key limitation is the relatively small and homogeneous sample, which restricts both the statistical power and the generalizability of the findings. While the sample size was adequate for exploratory analysis, a larger and more diverse sample would enable more robust conclusions and broader applicability across populations. Additionally, the study’s focus on a single cultural and educational context limits its ability to capture cultural variations in the expression of aggression and personality traits. Future research should incorporate participants from diverse cultural backgrounds and educational systems to better explore how cultural norms and values interact with personality traits to shape aggression.

Future research should also explore the role of other personality traits, such as openness to experience, in predicting aggression. Although openness was not found to be significantly related to aggression in this study, previous research has indicateed that it may influence how individuals interpret and respond to aggressive situations 9. Moreover, the potential moderating role of contextual factors, such as competitive versus non-competitive physical education environments, should be explored to understand how different settings may influence the expression of aggression among students with varying personality profiles.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the understanding of the relationship between Big Five personality traits and aggressive behavior in physical education students, with a particular focus on gender differences. Neuroticism, agreeableness, and conscientiousness emerged as significant predictors of different types of aggression, highlighting the importance of targeted interventions aimed at enhancing emotional regulation and prosocial behaviors. The findings underscore the need for gender-sensitive approaches to managing aggression in educational settings, thereby promoting a positive and supportive environment for all students.Future replication studies in varied cultural and institutional contexts will strengthen the evidence base for these recommendations.To address these limitations, future research should adopt a cross-cultural approach, incorporating diverse cultural and educational settings to validate the findings and ensure their applicability across different populations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Buss, A. H., Buss, A. H., Perry, M. & Perry, M. The aggression questionnaire. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452 (1992).

Eliot, L. Brain development and physical aggression: How a small gender difference grows into a violence problem. Curr. Anthropol. 62, S66–S78. https://doi.org/10.1086/711705 (2021).

Maneiro, L., Cutrín, O. & Gómez-Fraguela, X. A. Gender differences in the personality correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in a spanish sample of young adults. J. Interpers. Violence 37, NP4082–NP4107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520957697 (2022).

Costa, P. T. & McCrae, R. R. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 4, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5 (1992).

García-Sancho, E., Dhont, K., Salguero, J. M. & Fernández-Berrocal, P. The personality basis of aggression: The mediating role of anger and the moderating role of emotional intelligence. Scand. J. Psychol. 58, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12367 (2017).

Rehman, A. & Javaid, F. Examining the role of emotion regulation in the relationship between personality traits and aggression among university students. J. Asian Dev. Stud. 13, 685–702. https://doi.org/10.62345/jads.2024.13.3.585 (2024).

Bettencourt, B. A. et al. Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral conditions: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 132, 751–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.751 (2006).

Barlett, C. P. & Anderson, C. A. Direct and indirect relations between the Big 5 personality traits and aggressive and violent behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 52, 870–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.029 (2012).

Satchell, L. et al. Evidence of big five and aggressive personalities in gait biomechanics. J. Nonverbal Behav. 41, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-016-0240-1 (2017).

Anderson, C. A. & Bushman, B. J. Human aggression. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 53, 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231 (2002).

Hyatt, C. S., Chester, D. S., Zeichner, A. & Miller, J. D. Facet-level analysis of the relations between personality and laboratory aggression. Aggress. Behav. 46, 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21887 (2020).

Le, D. T. et al. Personality traits and aggressive behavior in vietnamese adolescents. PRBM 16, 1987–2003. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S405379 (2023).

Fahlgren, M. K., Cheung, J. C., Ciesinski, N. K., McCloskey, M. S. & Coccaro, E. F. Gender differences in the relationship between anger and aggressive behavior. J. Interpers. Violence 37, NP12661–NP12670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521991870 (2022).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2007).

Luo, J. & Dai, X. Y. Development of the Chinese adjectives scale of big-five factor personality IV: A short scale version. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 26(4), 642–646. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.04.003 (2018).

Fang, C. Z. Revision and preliminary application of the Buss-Perry Aggression Scale in college students [Master’s thesis]. Southwest University. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201602&filename=1016766259.nh2016). (2016).

Kaveh, M. H., Ghaysari, E., Ghahremani, L., Zare, E. & Ghaem, H. The effect of a theory-based educational intervention on reducing aggressive behavior among male students: A randomized controlled trial study. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 6308929. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6308929 (2022).

Tett, R. P. & Burnett, D. D. A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500 (2003).

Carver, C. S. et al. Serotonergic function, two-mode models of self-regulation, and vulnerability to depression: what depression has in common with impulsive aggression. Psychol. Bull. 134, 912–943. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013740 (2008).

Hofmann, W., Friese, M. & Strack, F. Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 4, 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x (2009).

Jones, S. E., Miller, J. D. & Lynam, D. R. Personality, antisocial behavior, and aggression: A meta-analytic review. J. Crim. Justice 39, 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.03.004 (2011).

Conroy, D. E. & Douglas Coatsworth, J. Assessing autonomy-supportive coaching strategies in youth sport. Psychol. Sport Exer. 8, 671–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.12.001 (2007).

Björkqvist, K. Gender differences in aggression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 19, 39–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.030 (2018).

Jiang, X., Li, X., Dong, X. & Wang, L. How the Big Five personality traits related to aggression from perspectives of the benign and malicious envy. BMC Psychol. 10, 203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00906-5 (2022).

Antoñanzas, J. L. The relationship of personality, emotional intelligence, and aggressiveness in students: A study using the big five personality questionnaire for children and adults (BFQ-NA). EJIHPE 11, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11010001 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to extend their heartfelt gratitude to all participants who generously dedicated their time to this study. Special thanks are owed to my family for their unwavering patience and encouragement throughout the demanding periods of data analysis and manuscript preparation. We are also deeply appreciative of the research assistants whose diligent efforts in administering the questionnaires and managing data entry were instrumental to our work. Lastly, we acknowledge the financial support from the Henan Province Education Science Planning Project, which was pivotal in enabling the successful execution of this research endeavor.

Funding

This work was supported by the Henan Province Education Science Planning Project(2024YB0184). The funders had no involvement in study design, data collection and analysis, decision-making regarding publication or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yugang Guo independently executed the study’s conceptualization and design. He personally managed data collection, performed a thorough analysis, and crafted the initial manuscript draft. Guo meticulously revised the document, ensuring academic excellence. He endorses the final submission and assumes full responsibility for the research’s integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Kinetic Science Experiment Ethics Committee at Beijing Sport University. All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Specifically, informed consent was obtained from all participants, their confidentiality was ensured, and their participation was voluntary.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y. Gender differences in the relationship between big five personality traits and aggression among physical education students. Sci Rep 15, 8122 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93038-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93038-w