Abstract

Segmental long bone defects present a significant clinical challenge as critical-size defects cannot heal spontaneously. Most studies focus on adult bone defects, with limited research on pediatric cases. To enhance the study of bone defects in children, we established a juvenile sheep bone defect model. Juvenile small-tailed Han sheep were used to create a 2 cm tibial bone defect, stabilized with a plate and screws. Tissue-engineered bone scaffolds were implanted at the defect site, and the limb was immobilized with a plaster cast for 3 months. Sheep were euthanized at 3 and 6 months post-surgery, and tibiae were examined using X-ray, microCT, and histological staining. Tibial defect models were established in 7 sheep, with 2 euthanized at 3 months and 5 at 6 months. X-ray revealed cortical bridging. MicroCT and histological staining showed new bone distribution, with the 6-month group demonstrating increased bone formation and bridging at the scaffold center. There was no significant difference in longitudinal growth rates between the operated and contralateral tibiae. We developed a reproducible model for juvenile tibial segmental defects in sheep, providing a robust basis for studying pediatric long bone segmental defects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Segmental bone defects in the long bone of limbs occur following the resection of lesions, such as bone cysts, bone tumors, bone infections, high-energy injuries, and congenital pseudoarthrosis. Although the bone tissue generally possesses significant regenerative and healing capabilities, the body cannot repair defects that exceed a certain length and are complicated by pathological changes1. Traditional treatment methods include autologous bone grafts, allogeneic bone grafts, bone transport techniques, and induced membrane techniques. However, all of these methods have shortcomings and limitations. In recent years, the rapid development of bone tissue engineering has introduced novel tissue-engineered bone materials, providing new options for the treatment of bone defects. Before the clinical application of these materials, researchers typically need to create bone defect models in animal experiments to study bone defect repair. Large mature animals, such as sheep, goats, pigs, and dogs, are considered the most clinically relevant models for preclinical testing2. Among them, sheep are frequently used to construct bone defect models due to their docile temperament, ease of maintenance, bone mineral composition and remodeling characteristics that closely resemble those of humans3.

In the existing studies, the long bones of sheep commonly selected include the femur, tibia, and metatarsal bones, with the tibia being the most frequently chosen. This preference is partly due to the high incidence of tibial fractures and defects in clinical practice and partly because of the thicker cortical bone in the sheep tibia, which reduces the occurrence of postoperative complications. The femur, located deep within the thigh muscle group, presents surgical exposure challenges4. While the metatarsal is near the foot, which increases the risk of surgical site contamination. Available fixation devices include intramedullary nails, plates, and external fixators. Locked intramedullary nails and plates are common fixation methods for human long bone fractures. The intramedullary nail serves as a load-bearing structure at the bone shaft’s center, but its use limits the filling of the bone implant. Plates can be pre-bent to match the contours of the bone shaft, providing rigid fixation to the defect site without restricting implant filling3. External fixators are easier to apply surgically but offer weaker fixation strength compared to plates and carry a higher risk of wound infection5.

However, variations in research protocols for segmental tibial defect models in long bones—such as differences in the age and sex of animals, bone fixation devices, and postoperative care—hinder the standardization of long bone defect models in large animals6. In terms of age, most animal experiments use adult animals, with results primarily intended to provide a basis for clinical trials in adults. Our team is dedicated to the study of pediatric bone trauma. Compared to adult bones, pediatric bones have a higher porosity, lower density7, and mineral content, as well as reduced bending strength, but they possess significant growth potential. After periosteal injury or fracture, increased blood supply to the bone leads to enhanced longitudinal growth8. Given the significant differences between adult and pediatric skeletons, research on adult bone defects cannot fully represent outcomes in pediatric orthopedics. To address the gap in the research on pediatric bone defects, we have established a model for treating segmental tibial bone defects in juvenile sheep using plate fixation and tissue-engineered bone scaffold implantation. Our model aims to lay the foundation for future studies evaluating the effectiveness of bone implants in treating segmental long bone defects of children. This article mainly demostrates the methods and key surgical techniques used in establishing this bone defect model, which helps advance research on treating bone defects in children clinically. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments.

Methods

Experimental animals

Seven juvenile small-tailed Han sheep (Beijing Long’an Laboratory Animal Breeding Center) aged 1–2 months, weighing 18.1–21.9 kg, with an equal mix of males and females, were housed in the model animal care center, with a temperature of 20–25 °C, humidity of 40–70%, 12-h lighting, and 12-h darkness. Sheep was housed in a standardized stainless-steel cage (dimensions 5 m × 5 m) and fed with feed, supplied twice a day at 5% of their body weight, with free access to water. All animals underwent quarantine requirements for 7 days. During this period, the health status indicators such as appearance, behavior, feces, and food intake of the sheep were observed. Prior to the animal experiments, a clinical veterinarian conducted a quality confirmation, and all the sheep met the experimental requirements.

Tissue-engineered bone scaffold

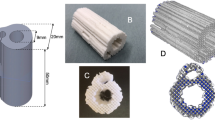

We utilized a biphasic composite bone scaffold for repairing segmental long bone defects, which was made of a simulated cancellous bone/cortical bone mineralized collagen material. The preparation process was as follows:

An ex vivo biomimetic mineralization technique was employed, wherein the self-assembly of collagen molecules facilitated the in-situ control of nano-hydroxyapatite (nHAp) crystal growth on collagen fiber molecules under ambient temperature and neutral pH conditions. This process led to the creation of biomimetic mineralized collagen fibers (referred to as MC in powder form). Initially, a simulated cortical bone scaffold was prepared using the melt 3D printing technique. PCL and nHAp were uniformly mixed and dissolved in 1,4-dioxane organic solvent. After thorough mixing, the solution was solidified and lyophilized to obtain a homogeneously mixed PCL/nHAp scaffold. The scaffold was then placed into the printer’s cartridge and extruded at 130 °C to form and cool down to room temperature. Subsequently, a simulated cancellous bone scaffold was prepared using an organic solvent freeze-drying dehydration method. PCL and nanosized MC were completely dissolved and homogenized in 1,4-dioxane at room temperature, then evenly poured into a mold containing the printed scaffold, ensuring any excessive air bubbles were eliminated. This was followed by an overnight pre-freeze at − 20 °C before freeze-drying dehydration. During the preparation of the simulated cancellous bone scaffold, the simulated cortical bone scaffold was incorporated and solidified. The simulated cortical bone scaffold provides sufficient mechanical support, while the simulated cancellous bone scaffold offers a regenerative conduit for cellular ingrowth. The dense bone material ensures ample mechanical support, and the cancellous bone material provides pathways for cell regeneration.

The biphasic composite bone scaffold had an outer diameter of 15 mm, an inner diameter of 8 mm, and a height of 20 mm, with the simulated cortical bone scaffold having a maximum expanse of 15 mm and a height of 20 mm. The simulated cancellous bone scaffold tightly encompassed a portion of the simulated cortical bone scaffold, facilitating structural support and cellular ingrowth and exchange after implantation.

Preoperative preparation

Food was withheld from the sheep for 24 h before surgery, though the water was allowed. Anesthesia was induced by intramuscular injection of xylazine hydrochloride injection (brand name: Sumianxin, ChangSha Best Biological Technology Co., Ltd.,) at a dosage of 0.01 mL/kg combined with 1–3% isoflurane (Jiangsu Hengfengqiang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) inhalation. Post-anesthesia, sheep were weighed, and anterior–posterior and lateral X-rays of both tibias were taken, with lateral X-rays captured in the left lateral recumbent position.

Sheep were then placed on the operating table in a prone position for tracheal intubation, connected to a ventilator, and positioned in right lateral recumbency. Throughout the surgery, an animal anesthesia machine (model SD-M2000A, Tianjin Shengdi Hengsheng Technology Development Co., Ltd.) was used to maintain inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane (1–3%). Electrocardiographic monitoring was used intraoperatively to monitor vital signs, keeping the heart rates maintained at 80–100 bpm, oxygen saturation at 80–90%, and tidal volume at 150–200 mL. The left hindlimb was prepared for surgery.

Surgical procedure

The surgical procedure was conducted with the sheep in a lateral position. The left hindlimb was disinfected with iodine twice, and a longitudinal incision was made on the anterior lateral side of the lower leg. After incising the skin and fascia, the exposed tibia was reached by dissecting through the muscle gap and exposing the bone by cutting the periosteum along the lateral aspect of the tibia. The bone membrane was detached from this segment using a periosteum separator. A plate (3.5 mm straight reconstruction locking titanium alloy plate, 8 holes, 10.5 mm, Beijing Fule Technology Development Co., Ltd) was placed on the anterior lateral surface of the tibia. The plate was pre-bent to ensure a snug fit against the bone cortex and was fixed with three screws at both the distal and proximal ends. The bone was marked at the center of the plate. Bone cuts were made at 1 cm intervals proximal and distal to the bone plate using a wire saw, with continuous physiological saline irrigations to minimize heat damage. A bone block measuring 2 cm was removed, including the bone membrane in that area. A prefabricated tissue-engineered bone scaffold, also measuring 2 cm in length, was then placed into the bone defect area. A suture (2.0 metric absorbable suture, ETHICON) was used to further stabilize the implantation. The skin was closed layer by layer, and the incision was wrapped with sterile gauze. Details are shown in Fig. 1.

The surgical procedure for tibial defect model. (a) Anesthesia in the right lateral position. (b) The anterolateral approach of the tibia, separating the muscles to expose the tibia. (c) Fitting the steel plate to the anterolateral aspect of the tibia. (d) Comparing with the bone scaffold, marking the length of bone resection. (e) Using a wire saw to resect the bone. (f) Completion of bone resection. (g) Comparing the resected bone with the bone scaffold. (h) Placing the bone scaffold and securing it with sutures.

Postoperative care

The left hindlimb was immobilized with a tubular plaster cast extending from 5 cm above the knee to 5 cm below the tibiotarsal joint. After recovering from anesthesia, sheep were returned to a unified pen for recuperation. Anti-infective therapy consisting of an intravenous drip of 180,000 units of penicillin sodium was administered once daily for 7 days. Pain relief was provided using Butorphanol hydrochloride injection (10 mL: 100 mg) via intramuscular injection at a dose of 0.01 mL/kg, administered twice daily for 7 days. Sheep were permitted partial weight-bearing activities while protected by the plaster cast on the left hindlimb. The plaster casts were changed monthly post-operation to monitor wound healing and assess the sheep’s daily activities.

X-ray examination

Seven sheep were randomly divided into two groups and euthanized at 3 months and 6 months post-surgery, respectively. The 3-month group consisted of 2 sheep, while the 6-month group included 5 sheep. X-rays of both tibiae were taken (Direct Digital Radiography Machine, kvp 40–60, mA 100–300), with lateral views uniformly captured in the right lateral position. Tibial length was measured in the lateral view, with the measurement taken from the midpoint of the tibial plateau to the midpoint of the ankle joint. The anteroposterior diameter of the tibia was measured at the central defect of the left tibia and the corresponding position on the right tibia, perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the tibia. Growth rates of the bilateral tibial length (the difference between the final measurement at euthanasia and the initial measurement, divided by the initial measurement) and anteroposterior diameter during the experiment were calculated and described using the mean ± standard deviation. A t-test was conducted on the 6-month group data to compare the growth of both tibiae.

Micro-CT scanning

Euthanasia was performed by isoflurane inhalation followed by an intravenous injection of potassium chloride solution (10 ml:1 g) at a dosage of 10–20 ml. After that, left hindlimb was incised along the original surgical incision, and the soft tissues surrounding the tibia were meticulously separated. The screws and plates were removed, and an osteotomy was performed 1 cm from both ends of the defect using a swing saw. The defect segment tissue was completely extracted and subjected to micro-CT scanning (Inveon MM CT, SIEMENS, voltage: 70 kV, current: 120 μA, pixel size: 20 μm). The scan data were reconstructed using COBRA_Exxim software (EXXIM Computing Corp., Livermore, CA) to assess the healing status of the defect area.

Histological analysis

Following the micro-CT scan, the excised bone tissue was processed for histological analysis. The detailed procedures for tissue processing are as follows: (1) Fixation: The tissue was immersed in 4% formalin at 4 °C for 48 h. (2) Dehydration: Dehydration was carried out through an ethanol gradient, progressing from low to high concentrations: 70%, 90%, 95%, and 100%. The tissue was immersed in 100% ethanol twice, each for 12 h. (3) Clearing: The tissue was then cleared in xylene twice, each for 2 h, to remove the ethanol. (4) Infiltration: The tissue was sequentially immersed in Technovite 9100 (Kulzer, Germany) mixed with xylene for 4 h, then in pure Technovite 9100 for 12 h, followed by infiltration in Technovite 9100 pre-embedding solution for 24–48 h. (5) Embedding: The tissue was embedded in Technovite 9100 and polymerized at − 14 °C for 3–5 days. (6) Sectioning: After polymerization, the embedded tissue block was trimmed to a suitable size and sectioned using a Leica RM2265 microtome to a thickness of 5 μm. (7) Resin Removal: The sections were immersed in pure ethylene glycol monoethyl ether acetate three times for 20 min each to remove the resin from the surface. (8) Dehydration: The sections were sequentially immersed in xylene, absolute ethanol, 95%, 90%, 70% ethanol, and distilled water, with each step lasting 10 min. (9) Drying: The sections were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h.

After sectioning, the tissues were stained using both Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) and Masson’s trichrome staining methods. The reagents used were sourced from HE and Masson staining kits (Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd.). The HE staining procedure was as follows: (1) Staining with 0.5% hematoxylin solution for 4–10 min, followed by rinsing with water for 1–3 min. (2) Differentiation in 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol for 5–15 s, followed by rinsing with water for 5–10 s. (3) Staining with 0.5% eosin Y solution for 30 s to 2 min, followed by rinsing with water for 30 s to 1 min. (4) Dehydration in a graded series of ethanol solutions: 70%, 90%, 95%, with each step lasting 2–3 s, followed by three 5–10 s dehydrations in 100% ethanol. (5) Clearing in xylene three times, each for 1–2 min. (6) Mounting with neutral gum.

The Masson’s trichrome staining procedure was as follows: (1) Staining with iron hematoxylin solution (containing 2% ferric chloride and 0.5% hematoxylin) for 5–10 min, followed by differentiation in 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol for 5–15 s. (2) Rinsing with water for 5–10 s, followed by counterstaining with 1% lithium carbonate solution for 3–5 min. (3) Rinsing with water for 1 min, then staining with Ponceau S–Fuchsin solution (containing 0.7% Ponceau S and 0.3% Fuchsin) for 5–10 min. (4) Washing with 0.2% acetic acid solution for 1 min, followed by differentiation in 1% phosphomolybdic acid solution for 1–2 min. (5) Washing with 0.2% acetic acid solution for 1 min, then staining with 2% aniline blue solution for 1–2 min. (6) Washing with 0.2% acetic acid solution for 1 min, followed by dehydration in a graded series of ethanol solutions: 70%, 90%, 95%, with each step lasting 2–3 s, followed by three 5–10 s dehydrations in 100% ethanol. (7) Clearing in xylene three times, each for 1–2 min. (8) Mounting with neutral gum.

Results

Statistical analysis was performed using standardized statistical software (Statistical Package for Social Science; version 26.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Data are described using the mean ± standard deviation. Comparison between groups is performed using the t-test for two independent samples. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Seven sheep bone defect models were successfully established (Table 1). In both the 3-month and 6-month groups, X-ray examinations (Figs. 2 and 3) indicated healing in the bone defect region, characterized by a slightly wider and denser defect area compared to the normal tibia. No malunions were observed in the tibia, and there was no deformation of the steel plates. Comparative X-ray analysis revealed that the growth rates in length and width of the operated-side tibia surpassed those of the contralateral side, although the difference in length growth rate was not statistically significant. Similarly, in the 3-month group, the growth rates of the tibia’s length and width were higher than those of the contralateral side, but statistical analysis was limited by the small sample size (Table 2).

Anatomical examinations of the left lower leg tibia (Fig. 2) showed that the bone defect area was encased in a hard bone cortex. Upon removal of the steel plate, the bone scaffold at the defect site remained observable and unabsorbed, with the internal texture of the defect area remaining soft. No complications such as skin pressure ulcers, malunion at the osteotomy site, or steel plate deformation were noted. MicroCT (Fig. 4) and hard tissue section staining (Figs. 5 and 6) demonstrated new bone distribution in the defect area, with new bone formation along the surface and center of the bone scaffold. The 6-month group exhibited more substantial new bone formation compared to the 3-month group, with new bone penetrating the scaffold’s center.

MicroCT of the tibial bone graft area. (a) 3-month group, illustrating new bone growth along the scaffold surface and center. The bone appears partially connected and partially wrapping around the scaffold surface, with incomplete penetration in the center. (b) 6-month sheep group, demonstrating increased and thickened new bone compared to the 3-month group. The new bone envelops the scaffold surface and penetrates through the scaffold center.

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of the tibial bone graft area. The microscope magnification was 0.2× for the overall image, with the magnified section shown at 10×. (a) 3-month group; (b) 6-month group. The pink area, indicated by the elliptical pattern, represents the bone tissue at the center of the defect; the pink area, indicated by the rectangular pattern, corresponds to the bone tissue on the outer side of the scaffold. As shown, at 3 months post-surgery, newly formed bone tissue is already surrounding the surface of the bone scaffold, but the center of the scaffold remains unconnected. At 6 months post-surgery, more new bone tissue has surrounded the scaffold, and new bone at the center of the scaffold is bridging and uniting the defect.

Masson’s trichrome staining of the tibial bone graft area. The microscope magnification was 0.2× for the overall image, with the magnified section shown at 10×. (a) 3-month group; (b) 6-month group. The blue area, indicated by the elliptical pattern, represents newly formed bone tissue. The red area, indicated by the rectangular pattern, represents mature bone tissue. As shown, at 6 months post-surgery, a significant amount of mature bone tissue has formed both around and within the center of the scaffold.

Throughout the experiment, all sheep were well-nourished and showed good development, with no observed diseases, surgical site infections, malunions, or skin pressure ulcers.

Discussions

In this study, we established an experimental animal model for the treatment of segmental bone defects in left tibia of small-tailed Han sheep using artificial bone implantation. This model serves as a novel large animal disease model for validating the potential transformation of artificial bone grafts into living bone. Over the past few decades, sheep models have been commonly used in bone regeneration research and have been designated as suitable models for bone implantation studies by the International Organization for Standardization 10993-69. Furthermore, they provide a comprehensive in vivo anatomical model for bone defect generation and bone healing after reconstruction, allowing for the assessment of various aspects of bone regeneration, such as bone marrow cavity implantation, cancellous bone localized defects, and segmental defects10. The selection of sheep as the experimental model is justified by their widespread use in livestock practices, ease of handling and maintenance, and cost-effectiveness for conducting large-scale studies. Significantly, the similarity in body weight between adult sheep and humans enables sheep biomechanical characteristics and loading dynamics to closely mirror those observed in human subjects11. Also, sheep bone tissue exhibits mechanical properties, morphological structure, and healing ability similar to human bone tissue9.

The establishment of the sheep bone defect model has involved the study of the femur, tibia, and metatarsal bones. Among these, the tibia is the most commonly used bone in the model due to the high incidence of tibial fractures in clinical practice and the high occurrence rate of segmental tibial defects. Additionally, the thicker cortical bone in the tibia compared to the femur implies a lower incidence of complications post-surgery, and the abundance of muscles and soft tissues around the femur increases the surgical difficulty3. The metatarsal bones, also classified as long bones in sheep, pose limitations on the surgical approach for bone defect modeling due to their short length and lack of muscle coverage around the metatarsal, which is an important source of mesenchymal cells and periosteal vascularization12. Moreover, the proximity of the metatarsal bones to the hooves increases the risk of wound contamination during activities, significantly raising the risk of wound infection.

A critical aspect in the establishment of the bone defect model is the type and size of the defect. The drill-hole defect model, commonly used in long bone defect studies, offers the advantage of creating multiple models in a single sheep without the need for additional fixation, thus avoiding interference with subsequent evaluations10. However, this model is limited to the study of bone repair materials that do not require strong support, such as bone powder or bone granules. With the advancement of 3D printing technology and bone repair materials, there is an increasing focus on the development of bone repair materials with high-strength support and rapid degradation. Therefore, the establishment of segmental bone defect models provides a better platform for studying the performance of new bone repair materials. Previous studies have validated that the range of critical bone defects in the tibia of sheep is approximately 1.5–2 times the diameter of the diaphysis13. In this experiment, the average transverse diameter of the tibia in sheep was 10.4 ± 0.7 mm. We selected an osteotomy length of 2 cm, which meets this standard. Some studies have created bone defect models in multiple limbs of a sheep, thereby increasing the number of models but also prolonging the surgical time, increasing the occurrence rate of anesthetic complications, significantly increasing the load bearing of the limbs, and potentially influencing the healing process. However, we believe that surgery on both hindlimbs would severely impact the postoperative activity of the sheep, which has a negative effect on postoperative recovery11. To ensure the effectiveness of each model, we chose to create only one bone defect in each sheep.

Regarding the fixation methods for the limbs, previous reports have included the use of plates, intramedullary nails with locking screws, and external fixation frames, and there is currently no direct comparison of these fixation methods for segmental tibial defects. External fixation frames have been used to fix 3.5 cm-long tibial defects in a study, and the authors suggested that the fixation strength of the external fixator is slightly weaker than that of the plate, but it may generate more mechanical stimulation at the graft site14. However, the probability of skin wound infection at the needle insertion site of the external fixator is relatively high, adding to the difficulty in postoperative care of the sheep5. Furthermore, the effective utilization of intramedullary nails with locking screws to address segmental defects in adult sheep has been well-documented in numerous research studies. It has been proposed that intramedullary nails can induce dynamic alterations at the graft site without necessitating additional manipulation of the bone graft region. This capability enables the performance of mechanical tests, such as torsional and compressive strength evaluations on the limb post-healing5,15,16,17. Besides, the smaller diameter of the medullary cavity poses a significant challenge to the use of intramedullary nails in both young sheep and children. In addition, intramedullary fixation limits the shape of the implanted bone scaffold, allowing only hollow bone tissue scaffolds to be inserted. Due to these constraints, we have chosen to utilize plate screw fixation for stabilizing the bone defect. Previous studies have successfully employed plates in conducting experiments on segmental bone defects in sheep, and various plate sizes tailored to the bone dimensions of children at different stages of growth are commonly used in clinical practice18,19,20,21,22. Plate fixation offers sufficient stability and does not restrict the shape of the implant, providing effective support to the bone defect area.

During the surgical process of this animal model, we disrupted the periosteum of the segmental bone, as the periosteum provides a large number of osteogenic cells and vascular plexus to promote bone healing and regeneration23. In common segmental bone defects seen clinically such as bone tumors, fractures, and osteomyelitis, the periosteum at the defect end is typically not intact. To approximate a realistic disease model, we performed an extensive periosteal excision in the segmental bone.

Postoperative care of the healing process is a major challenge, as sheep are unable to follow medical advice to rest and reduce limb activity, unlike humans. While some studies have overlooked postoperative limb care, we believe this is an essential aspect of establishing a standardized model14,20,24. In previous models, it was observed that some limbs experienced plate deformation following plate fixation without additional protection, indicating that sole plate fixation may not provide sufficient protection to the segmental bone19. Therefore, we utilized plaster fixation on the operated limbs of juvenile sheep to provide limb protection and support for weight-bearing. The plaster fixation was applied above the knee and below the ankle joint to prevent displacement during activities. Different from adult sheep, juvenile sheep exhibit continuous limb growth. In our study, both the left and right tibias of the seven juvenile sheep have significant thickening and elongation. Therefore, there is a noticeable widening of the defect area resulted from bone tissue growing along the bone scaffold. Consequently, the increasing pressure within the plaster casts necessitated regular adjustments. To mitigate the impact of this pressure and prevent the occurrence of pressure sores, we replaced the plaster casts every month for sheep involved in longer-term studies. Notably, our model did not exhibit any instances of plate deformation or fractures in the bone defect areas, indicating that the combination of plate and plaster cast fixation provided sufficient stability throughout the study.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the lack of direct verifications that a 2 cm defect would not heal naturally. Previous research has established that the critical bone defect range for sheep tibiae is approximately 1.5–2 times the diaphysis diameter13. In animal experiments validating bone repair materials in adult sheep, the tibial defect lengths typically range from 20 to 30 mm25. Given that the tibial diameter in juvenile sheep is significantly smaller than in adults, the 2 cm defect used in our model falls within this range. Additionally, the cross-sectional shape of the sheep tibia is not perfectly circular; the anteroposterior diameter is longer than the mediolateral diameter. Therefore, we used the anteroposterior diameter measured from the lateral X-ray to estimate the critical bone defect size, which may be slightly overestimated compared to the actual value. Following the 3R principles of animal experimentation, we did not use additional sheep to directly verify the critical defect size. Furthermore, this study primarily focuses on the surgical techniques and care methods involved in establishing the defect model, consequently deemphasizing the role and analysis of implant materials. Implant materials are a crucial component of bone defect healing, and different materials may result in varied healing outcomes. Therefore, we plan to conduct further research and analysis on tissue-engineered bone materials to address this aspect comprehensively in future studies.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a model combining plate fixation and tissue-engineered bone scaffold implantation to treat 2 cm segmental tibial defects in juvenile sheep. Verifications through gross anatomy, X-ray imaging, microCT, and hard tissue staining confirmed varying degrees of healing in all sheep models. As the healing time increased, bone regeneration has significantly improved. No complications were observed, demonstrating the reliability of the model and care procedures. This model effectively simulates the treatment of pediatric segmental long bone defects and facilitates the assessment of various tissue-engineered bone grafts. In summary, the model we developed is easy to establish, reproducible, and very close to clinical treatment protocols, which has important value for future research on tissue-engineered bone materials.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cheng, B. C. et al. A comparative study of three biomaterials in an ovine bone defect model. Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 20, 457–464 (2020).

Reichert, J. C. et al. The challenge of establishing preclinical models for segmental bone defect research. Biomaterials 30, 2149–2163 (2009).

Sparks, D. S. et al. A preclinical large-animal model for the assessment of critical-size load-bearing bone defect reconstruction. Nat. Protoc. 15, 877–924 (2020).

Jones, C. W. et al. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation in sheep: Objective assessments including confocal arthroscopy. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. 26, 292–303 (2008).

Margolis, D. S. et al. A large segmental mid-diaphyseal femoral defect sheep model: Surgical technique. J. Investig. Surg. Off. J. Acad. Surg. Res. 35, 1287–1295 (2022).

McGovern, J. A., Griffin, M. & Hutmacher, D. W. Animal models for bone tissue engineering and modelling disease. Dis. Models Mech. 11, dmm033084 (2018).

Light, T. R., Ogden, D. A. & Ogden, J. A. The anatomy of metaphyseal torus fractures. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 188, 103–111 (1984).

Brighton, C. T. Longitudinal bone growth: The growth plate and its dysfunctions. Instr. Course Lect. 36, 3–25 (1987).

Hutchens, S. A., Campion, C., Assad, M., Chagnon, M. & Hing, K. A. Efficacy of silicate-substituted calcium phosphate with enhanced strut porosity as a standalone bone graft substitute and autograft extender in an ovine distal femoral critical defect model. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 27, 20 (2016).

Hettwer, W. et al. Establishment and effects of allograft and synthetic bone graft substitute treatment of a critical size metaphyseal bone defect model in the sheep femur. APMIS Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 127, 53–63 (2019).

Atayde, L. M. et al. A new sheep model with automatized analysis of biomaterial-induced bone tissue regeneration. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 25, 1885–1901 (2014).

Viateau, V. et al. A technique for creating critical-size defects in the metatarsus of sheep for use in investigation of healing of long-bone defects. Am. J. Vet. Res. 65, 1653–1657 (2004).

Boer, FCd. et al. New segmental long bone defect model in sheep: Quantitative analysis of healing with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. 17, 654–660 (1999).

Kon, E. et al. Autologous bone marrow stromal cells loaded onto porous hydroxyapatite ceramic accelerate bone repair in critical-size defects of sheep long bones. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 49, 328–337 (2000).

Dozza, B. et al. Nonunion fracture healing: Evaluation of effectiveness of demineralized bone matrix and mesenchymal stem cells in a novel sheep bone nonunion model. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 12, 1972–1985 (2018).

Lozada-Gallegos, A. R. et al. Development of a bone nonunion in a noncritical segmental tibia defect model in sheep utilizing interlocking nail as an internal fixation system. J. Surg. Res. 183, 620–628 (2013).

Schneiders, W. et al. In vivo effects of modification of hydroxyapatite/collagen composites with and without chondroitin sulphate on bone remodeling in the sheep tibia. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. 27, 15–21 (2009).

Klaue, K. et al. Bone regeneration in long-bone defects: tissue compartmentalisation? In vivo study on bone defects in sheep. Injury 40(Suppl 4), S95-102 (2009).

Li, J. J. et al. A novel bone substitute with high bioactivity, strength, and porosity for repairing large and load-bearing bone defects. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, e1801298 (2019).

Liu, W. et al. Fabrication of piezoelectric porous BaTiO3 scaffold to repair large segmental bone defect in sheep. J. Biomater. Appl. 35, 544–552 (2020).

Niemeyer, P. et al. Comparison of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue for bone regeneration in a critical size defect of the sheep tibia and the influence of platelet-rich plasma. Biomaterials 31, 3572–3579 (2010).

Teixeira, C. R. et al. Tibial segmental bone defect treated with bone plate and cage filled with either xenogeneic composite or autologous cortical bone graft. An experimental study in sheep. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. VCOT 20, 269–276 (2007).

Tate, M. L. K., Dolejs, S., McBride, S. H., Miller, R. M. & Knothe, U. R. Multiscale mechanobiology of de novo bone generation, remodeling and adaptation of autograft in a common ovine femur model. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 4, 829–840 (2011).

Decambron, A. et al. Low-dose BMP-2 and MSC dual delivery onto coral scaffold for critical-size bone defect regeneration in sheep. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. 35, 2637–2645 (2017).

Bow, A. J. et al. Temporal metabolic profiling of bone healing in a caprine tibia segmental defect model. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 1023650 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to experimental animals for sacrificing their lives for the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S.and H.Z. participated in the design of the experiment, the process of the experiment, and the writing of the manuscript. Q.W. applied for funding for the experiment, participated in the design of the experiment, and the revision of the manuscript. D.Z and Y.W. participated in the process of the experiment and data processing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Committee for Animal Welfare and Ethical Review (IACUC-D2021023). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, S., Zhang, H., Wang, Q. et al. Establishment of a novel experimental animal model for the treatment of tibial segmental bone defects in juvenile sheep. Sci Rep 15, 8232 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93172-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93172-5