Abstract

Upon their arrival in the water column, coral larvae use physical and chemical cues to navigate toward a suitable habitat and begin their settlement process. To engineer substrates that influence settlement, it is important to have quantitative data about the types and concentrations of chemicals that elicit desired behavioral responses before and after contact with the substrate. Here, we quantified the behavioral and morphological responses of coral larvae (Colpophyllia natans and Orbicella faveolata) to crustose coralline algae exudates (CCA) and ions found in coral skeletons using chemotactic assays in microfluidic channels. Multiple larvae in each channel were tracked over 30 min to quantify their overall attraction or repulsion to the presence of various dissolved chemical cues. Larvae showed repulsion to \({\text{MgC}}{\text{l}}_{2}\), attraction to both \({\text{CaC}}{\text{l}}_{2}\) and CCA exudates, and both attraction and repulsion to \({\text{SrC}}{\text{l}}_{2}\), depending on the concentration. The behavioral and morphological changes exhibited by individual larvae were investigated as well. Using particle tracking methods to quantify larval behavior, we found that the typically straight swimming larvae of C. natans increased turning behavior in regions with high concentrations of CCA exudates and \({\text{CaC}}{\text{l}}_{2}\), a behavior associated with local searching, while they decreased turning behavior near high concentrations of \({\text{MgC}}{\text{l}}_{2}\). We also found that larvae shrink in length when exposed to 50× the seawater concentration of calcium, a potential stress or escape response, while these larvae elongated when exposed to CCA exudates, a morphological response associated with benthic contact and crawling. These results highlight the value of direct observation in understanding the interplay between coral larvae and their chemical environment. Incorporating cues such as calcium or CCA exudates into artificial substrates can elicit specific behavioral and physical changes in coral larvae, thereby enhancing settlement and contributing to reef restoration efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine organisms employ many navigational skills as they travel across ocean environments in search of optimal conditions for survival and reproduction. The ocean presents a wide range of biological1,2,3,4,5, chemical6,7,8,9, and physical10,11,12,13 influences. Among marine organisms, coral larvae represent a particularly important subject of study due to their role in sustaining coral reef ecosystems. Coral reefs play a vital role in supporting biodiversity. However, they are currently facing unprecedented threats, including climate change, coral bleaching, and habitat degradation14,15,16. Recognizing the pivotal role that coral larvae play in the recovery and resilience of these ecosystems, there is growing interest in developing targeted strategies for coral reef restoration through larval recruitment17,18,19. One emerging restoration approach involves designing artificial substrates that use surface topological features, create flow structures, or employ chemical attraction to aid in coral larval settlement19,20,21. By understanding the intricacies of how larvae locate and settle onto substrates, researchers can design effective synthetic substrates that enhance coral recruitment and promote reef recovery.

Some past studies have highlighted the significance of chemical cues in shaping the recruitment success and metamorphosis rates of coral larvae22,23. However, the marine environment is inherently dynamic, with chemical gradients that fluctuate over time, adding complexity to the navigational and behavioral strategies of coral larvae. Additionally, environmental factors such as UV radiation24, pressure changes25, and salinity stress26 have been shown to influence larval behavior and survival. While data from coral larvae remain limited, studies on other marine organisms have quantified a variety of swimming and morphological changes that occur in response to chemical gradients, such as changes in swimming speed and direction27,28, increased turning behaviors29,30, and alterations in morphology31,32. Understanding these responses is essential for deciphering how marine organisms interact with and adapt to their chemical environments.

In coral ecology, crustose coralline algae (CCA) are well-known natural inducers of coral settlement1,6,33,34. Chemical compounds derived from CCA, including TBP (Tetrabromopyrrole)35, sulfated glycosaminoglycan36, glycoglycerolipids, and polysaccharides34, have been demonstrated to actively facilitate coral larval settlement and metamorphosis. There is also an intricate connection between intracellular divalent calcium transients, calcium signal-related gene expression, and larval metamorphosis and settlement, leading to the prospect of inducing coral larval settlement through the introduction of Ca2+23,37. Calcium and magnesium also play a pivotal role in the adhesion of bacteria, algae38, and coral larvae23. For instance, Mg2+/Ca2+ promotes the adhesion of marine bacteria and algae such as Bacillus sp. and Chlorella sp., presumably by regulating the aggregation and formation of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)38. In addition, magnesium and strontium are elemental constituents found within the coral skeleton, and Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios are used as indicators of water chemistry over time39,40,41,42. Given the integral role of calcium, magnesium, and strontium in marine organism settlement and attachment, coral skeletal structure, and overall water chemistry, investigating their effects on larval behavior and settlement could uncover novel insights into the intricate interplay between water chemistry and coral recruitment.

One way to study and quantify chemotactic responses is by using microfluidic devices. Microfluidic chambers have been used to study the chemosensory behavior of a variety of small organisms, including bacteria43, flatworms44, and marine larvae like corals45. These devices enable the creation of a simplified system with precise, reproducible chemical gradients and allow for direct, real-time observation of larval behavior at a microscale level. The use of microfluidics facilitates a systematic exploration of how different chemical stimuli influence the behavior of coral larvae, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying their chemotactic responses.

This study uses microfluidics to examine the chemotactic responses of Caribbean coral larvae (Colpophyllia natans and Orbicella faveolata) to organic and inorganic cues at the larval scale. Previous studies on Orbicella faveolata have shown that larval settlement can be induced by specific CCA species, such as Hydrolithon boergesenii and Titanoderma prototypum, which provide biochemical attachment and metamorphosis cues5,46,47. However, these CCA species are often scarce on degraded reefs, potentially limiting recruitment success. While studies on O. faveolata have highlighted the importance of CCA-derived cues, larval responses to inorganic ions remain comparatively underexplored. Larval settlement of the coral species Colpophyllia natans is even less studied, with limited research on settlement preferences and chemotactic responses19,48. The current study seeks to fill these gaps in knowledge by performing detailed chemotactic assays in microfluidic channels to observe how larvae respond to gradients of CCA exudates, and calcium, strontium, and magnesium ions. The focus was on measuring the type of responses—whether attractive or repulsive, and quantifying changes in larval speed, morphology, and the extent of their turning behaviors under different chemical stimuli. These observations demonstrate the potential utility of inorganic materials like calcium in the design of artificial substrates aimed at attracting coral larvae and promoting their settlement on coral reefs.

Methods

Gamete collection and larval rearing

Gametes were collected from the hermaphroditic Caribbean broadcast-spawning corals Colpophyllia natans (Boulder Brain Coral) and Orbicella faveolata (Mountainous Star Coral) at Playa Zakitó, Curaçao (also known as Water Factory; 12° 6′ 34″ N, 68° 57′ 18″ W) in September 2022. Egg-sperm bundles were collected from C. natans and O. faveolata colonies at a depth of 5–10 m. Larvae were reared following previously published methods21,26,49,50,51. Gamete bundles were mixed in 1 L polycarbonate fat separators and left for 1 h to allow for fertilization. Fertilized embryos were then rinsed with 0.5 µm filtered sea water to remove excess sperm until the water was clear. Developing embryos were transferred to 1 L clear polystyrene clamshell food containers with approximately 800 mL FSW to develop into larvae. Larvae were separated from unfertilized eggs and lipid detritus by siphoning or by rinsing larvae over a 150 µm nylon mesh filter. Water changes and container changes were performed approximately every 2 days. All larval rearing steps and experiments were performed with 0.5 µm filtered seawater (FSW; spun polypropylene sediment filters, sequential pore sizes of 50 µm, 20 µm, 5 µm, and 0.5 µm, H2O Distributors, Marietta, GA). Colpophyllia natans larvae had a length of 471 ± 51 μm and width of 244 ± 21 μm (mean ± SE, N = 30). Orbicella faveolata larvae had a length of 386 ± 42 μm and width of 270 ± 19 μm (mean ± SE, N = 30).

Fabrication of microfluidic channels

The chemotaxis experiments were performed in microfluidic channels made from Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, SYLGARD 184, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) with a base to curing agent ratio of 10:1. This mixture was poured onto a rectangular tray to a height of 4 mm and cured overnight at 50 °C. Then, using a 2D pill-shaped leather punch (of length 30 mm and width 6 mm), channels of length 45 mm and width 6 mm were punched out with two overlapping cuts. The channels were then cleaned with Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) and dried using compressed air. A glass slide was treated with Acetone, IPA, and Deionized (DI) water. Both surfaces were then plasma-treated by passing a high-potential electrode over them, generating a corona discharge that created reactive chemical groups. These reactive groups facilitated covalent bonding, allowing the channel to bond securely to the glass slide. The channels were left open on the top.

Experimental procedure

For the chemotaxis experiments, 1 mL of Filtered Sea Water (FSW) and 20–30 coral larvae were pipetted into the microfluidic channels. The larvae were allowed to swim for 5–10 min in the channels before the introduction of chemical cues to ensure uniform larval distribution. Then, 10 µL of one of the chemical solutions was introduced to one end of the channel. The location of the chemical injection was in one end for half the channels and on the opposite end for the other half, to control for external variables. For each set of experiments, one of the channels was injected with FSW as the control. The orientation of the channels was also changed with respect to the room and light sources for each experiment, to ensure that external conditions did not bias the experiment. Experiments were started 2 days after spawning for each species and were performed every other day until 8 days after spawning (C. natans) or 4 days after spawning (O. faveolata). Only half of the experiments were performed on the 8th day after spawning for C. natans due to a lack of available swimming larvae. Experiments were repeated each test day for each solution (n = 3).

The chemicals used in this study were \({\text{CaC}}{\text{l}}_{2}\text{, MgC}{\text{l}}_{2}\text{, SrC}{\text{l}}_{2}\), and CCA exudates. The concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, and Sr2+ were 800, 4000, and 20,000 ppm for Ca2+, 2600 and 13,000 ppm for Mg2+, and 16, 80, and 400 ppm for Sr2+. These concentrations correspond to 2×, 10×, and 50× the concentration found in sea water for Ca2+ and Sr2+ and 2× and 10× the sea water concentration for Mg2+. CCA exudates from Hydrolithon boergesenii were produced using previously published methods52. Briefly, CCA fragments were collected from the reef in front of CARMABI Research Station. Fragments with a total surface area of ~ 200 cm2 were placed in 1 L glass beaker containing 500 mL of FSW, and incubated in a flow-through aquarium system to maintain stable temperature for 12 daylight hours, as the CCA released organic exudates (i.e., exometabolites) into the surrounding seawater. The sample was then filtered (pre-rinsed, 0.22 µm polyethersulfone filter cartridge; Sterivex, Millepore) and acidified to pH 2. CCA exudates were then isolated from the samples using cleaned and activated PPL solid phase extraction (SPE) resin cartridges (Bond Elut Priority PolLutant; Agilent), which retain specific, primarily polar fractions of organic compounds. Cartridges were dried with nitrogen gas. Later, to extract the CCA exudates from the PPL columns, HPLC-grade methanol was employed as an eluent and the methanol fractions were then evaporated under nitrogen gas in acid-washed, glass scintillation vials, leaving CCA exudate solids. Prior to beginning chemotaxis experiments, the CCA exudate solids were re-suspended in 0.5 µm filtered seawater.

Imaging and data analysis

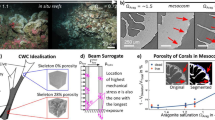

For each experiment, six microfluidic channels containing the coral larvae and cue solutions were placed on the imaging platform (Fig. 1a,b). A camera (model MQ042MG-CM, Ximea) with a macro lens (NIKKOR 24-85 mm f/2.8-4D IF Zoom Lens, Nikon) was attached to the optical breadboard (12″ × 12″ × 1/2″ aluminum breadboard, Thorlabs) directly above the channels to capture larval movement (Fig. S1). Two light sources (L132T 0.78″ LED lights, Viltrox) were placed on opposite sides of the platform to provide light for imaging and set to 100% brightness for the duration of the experiments. All six channels fit within the camera field of view. The videos were captured at a frame rate of 2 fps and a spatial resolution of 40 µm/pixel throughout the experiment (Video S1). The larvae were directly imaged for 30 min as they explored the channels filled with chemical cues.

Device setup and imaging for coral larva chemotaxis experiments. (a) Schematic showing the chemotaxis microfluidic channels and camera orientation. (b) Visualization of chemical cue gradients in the microfluidic channels. The dye is injected in the left end of the channel and the relative concentration of the dye at each point in the channel is represented by the gray value at that point. Clock icons indicate 1, 15, and 30 min incubations. (c) Maximum intensity projections showing the distribution of the Copophyllia natans and Orbicella faveolata larvae in control channels. Figures show larval positions for 240 frames (2 min) overlayed into a single image after the FSW control cue was introduced to the left ends of the channels. (d) Probability distribution functions of swimming speed for the C. natans and O. faveolata larvae in control channels.

Chemical diffusion in the channels was visualized using a food dye (Fig. 1c). An initial volume of 10 µL of dye was injected at an end of the channel, and the diffusion process was recorded over a period of 30 min. This dye was used only for the visualization of chemical gradients that could occur in the channels and was not present in the channels during larval experiments. For all chemicals used, the chemical was initially concentrated around the injection point and there was no chemical detectable in the rest of the channel. The chemical diffused through the channel over time, decreasing in concentration at the injection site and increasing concentration in the rest of the channel (Fig. S2). There was an observable gradient from the highest concentration at the injection point to the lowest concentration at the opposite end of the channel at all times. In addition, the diffusion times of the tested chemical cues were qualitatively estimated from their molecular weights. The inorganic chemicals consisted of smaller molecules than the food dye used and would diffuse more rapidly. In contrast, the CCA exudates, although their exact composition remains unidentified, consist of relatively heavy molecules and would diffuse more slowly than the inorganic chemicals.

Image analysis was used to compute the centroids, position in the channel, and velocity of each larva, using a particle tracking algorithm in MATLAB53. The speed distribution for C. natans was strongly bimodal, with peaks at 0 ± 0.2 and 2.7 ± 0.2 mm/s (Fig. 1d). Orbicella faveolata only exhibited a small peak at 2.5 ± 0.2 mm/s in addition to the peak at 0 ± 0.2 mm/s. The peak at zero in both distributions was due to larvae slowing down or stopping when they encountered the chamber walls. Global statistics such as the distribution of larvae in the channel, their average swimming speeds, and position frequency distributions in the presence of different chemicals were also calculated.

To compute larval distribution, position data were aggregated into two-min intervals and a Migration Index (MI) value was calculated for every five min of the experiment. Aggregation was applied to minimize the impact of repeated measurements. Although the chemical gradient changes over time, the diffusion distance was comparable to the larval body length, making the gradient effectively stationary within the aggregated bins. Based on Fick’s second law, 1D chemical diffusion distances can be estimated as, \(\text{x = }\sqrt{\text{2Dt}}\), where D is the diffusion coefficient and t is the time. Assuming a diffusivity range of \(10^{ - 10} - 10^{ - 9} \;{\text{m}}^{2} /{\text{s}}\), which corresponds to typical ion diffusivities in aqueous environments54,55,56, the chemical gradient was estimated to travel distances of 150–490 µm over a 2-min interval. The larval body length in this study ranges from 250 to 400 µm.

The MI was defined as follows:

An MI value of 0.5 indicates that the larvae are evenly distributed between the two halves of the channel. Values higher than 0.5 indicate that the larvae accumulated near the region of high chemical concentration and values lower than 0.5 indicate larvae accumulated away from the chemical.

To determine the average speed of the larvae as a function of their position in the channel, the channel was divided into nine bins of length 5 mm and the average value in each bin was calculated. The position and velocity data were aggregated into 2-min intervals for every five min of the experiment to investigate the temporal variation in the average speeds.

To determine the time larvae spent in different positions within the channel, the channel was divided into 20 bins of length 2.25 mm along the x-axis and three 2 mm bins along the y-axis. The number of larvae in each bin was counted, using data aggregated over 2-min intervals for every 5-min throughout the experiment. These counts were normalized by the total number of larvae in the channel and then summed. This process was repeated for all chemical treatments and the control channel. The final heatmap for each chemical was obtained by subtracting the control channel heatmap from the chemical-specific heatmaps. Considering an average number of 25 larvae in each channel, here a value of 10 indicates that there is at least one more larva in that specific bin compared to the control. A value of zero indicates no difference between the chemical treatment and the control in that bin.

Individual statistics such as the tortuosity of the swimming trajectories and the length and width of larvae in the presence of different chemicals were also computed. For a known trajectory, the tortuosity was defined as follows:

A tortuosity value of 1 indicates a straight-line trajectory, whereas an infinite tortuosity signifies a circular trajectory. Tortuosity serves as an indicator of the extent to which larvae are turning as they swim.

To determine the length and width of the larvae, snapshots of the channel were analyzed at five-min intervals throughout the experiment. Each larva was fitted into an ellipse, and the major and minor axes were measured. Measured dimensions were scaled using the index of refraction of seawater to account for magnification in the water. Mean values for 30 larvae per condition across multiple channels are presented here.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate differences in larval distribution between treatments and the control, we used migration index (MI) as the metric. The MI values were computed for the entire duration of 30 min (3600 frames) and aggregated into 240-frame bins (corresponding to 2-min intervals). To reduce potential spurious differences unrelated to the chemical gradient, the first and last 120 frames (1 min) were excluded from the analysis.

Following aggregation, one-way ANOVA was performed at each time bin to compare the mean MI of each treatment against the control independently. Each treatment consisted of three wells (n = 3), and comparisons were conducted independently for each 2-min bin. Treatments that resulted in an MI significantly different from the control for at least two min were considered significant and indicated with an asterisk on the violin plots. These violin plots display data from all three wells and all time bins for each treatment, providing an overview of MI distribution. The full workflow is summarized in Fig. S3.

Additionally, for each treatment, the lowest p value observed across all time bins (indicating the most significant difference from the control) was recorded along with the mean and standard deviation of MI values (Tables S1–S4).

Results

Effect of chemical cues on the larval migration index (MI)

Coral larvae exhibited attractive (MI > 0.5), repulsive (MI < 0.5), or neutral (MI ~ 0.5) behavioral responses depending on the chemical treatment introduced into the microfluidic channel. These larval responses were time dependent as the chemical cue solutions diffused within the microchannels. The values of larval migration index at different times across the duration of the experiment showed the time dependence of responses (Fig. 2). The introduction of inorganic cues resulted in a larval distribution that was different from that observed with the organic cue CCA (Fig. 2c,d).

Coral larvae change chemotactic responses through time. Larval migration index (MI) is shown as a function of time for inorganic and organic chemical cues. The colored regions show one SE from the mean. (a) MI for inorganic cues 50× Ca2+ and 10× Mg2+ for C. natans larvae. (b) MI for inorganic cues 50× Ca2+ and 10× Mg2+ for O. faveolata larvae. (c) MI for the organic cue crustose coralline algae exudates (CCA) and inorganic cue 50× Ca2+ for C. natans larvae. (d) MI for the organic cue CCA and inorganic cue 50× Ca2+ for O. faveolata larvae.

For C. natans in the control conditions (FSW), the larval distribution remained uniform over time, i.e., near the mean MI of 0.5 (Fig. 2a, Videos S2 and S3). Whereas, after 1 min of introducing 50× Ca2+, the mean MI reached a value of 0.7 ± 0.07, indicating that 70% of the larvae aggregated in the region near chemical injection. MI increased to a peak of 0.83 ± 0.03 after 5 min, indicating that 84% of larvae aggregated in the region of higher chemical concentration (Fig. 3a, Videos S6 and S7). After 30 min, MI had reverted to 0.62 ± 0.07, signifying an approach to uniform distribution of larvae. For 10× Mg2+, the larvae started out uniformly distributed. Then MI decreased, reaching a minimum of 0.38 ± 0.07 after 10 min, indicating that 38% of the larvae were in the region of higher chemical concentration (Fig. 2a, Videos S4 and S5). Within 25 min, MI reverted to 0.47 ± 0.06, indicating a return to uniform distribution.

Chemical cue, cue concentration, and larval age affect chemotactic behavior of coral larvae. Distributions of larval migration index (MI) for all the chemicals tested as a function of larval age over 30 min of observation (Mean \(\pm\) SD values are reported in the text). The larvae show attractive (MI > 0.5), repulsive (MI < 0.5), or neutral (MI ~ 0.5) chemotactic responses. (a–c) MI distributions of C. natans larvae 2, 4, and 6 days after spawning, respectively. (d,e) MI distributions of O. faveolata larvae 2 and 4 days after spawning. Ion concentrations are reported relative to their naturally-occurring concentrations in local seawater. (f) Variation of MI as a function of age for control, 50× Ca2+, 10× Mg2+, and 50× Sr2+ for C. natans larvae. Each treatment includes three replicates (n = 3). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between treatment and control on the respective day for at least two min during the experiment (p < 0.05).

For O. faveolata in the control channel (FSW), the larval distribution was uniform for all of the time points observed (Fig. 2b). For 50× Ca2+, the larvae started out uniformly distributed and then MI increased, reaching a peak of 0.63 ± 0.06 at 5 min, indicating that 65% of larvae had aggregated in the region of higher Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 2b). After 20 min, MI reverted to 0.58 ± 0.05, signifying an approach to uniform distribution. For 10× Mg2+, the larvae started out uniformly distributed and then MI decreased, reaching a minimum of 0.43 ± 0.05 after 10 min, indicating that only 43% of the larvae were present in the region of higher chemical concentration (Fig. 2b). Within 20 min, MI reverted to 0.53 ± 0.05, indicating a return to uniform distribution.

In CCA treatments, both C. natans and O. faveolata larvae started accumulating near the point of injection within 1 min. Mean MI values of 0.69 ± 0.05 and 0.58 ± 0.08 indicated that 69 and 58% of the larvae, respectively, accumulated near the point of injection (Video S8). After 15 min, MI had increased, reaching peaks of 0.79 ± 0.05 and 0.90 ± 0.04, indicating 79 and 90% aggregation near the region of the injection, respectively (Fig. 2c,d, Video S9). Larval distribution then stabilized at these higher levels until the end of the 30-min observation period, contrasting with the Ca2+ treatments, in which MI decreased after reaching a peak.

Statistical analysis of MI-based larval behavioral responses

Coral larvae exhibited attractive (MI > 0.5), repulsive (MI < 0.5), or neutral (MI ~ 0.5) behavioral responses depending on the chemical treatment and concentration introduced into the microfluidic channel. The strength of these responses varied with larval age. Violin plots depict the distribution of MI values across the entire experimental duration and replicates, summarizing the effects of each treatment relative to the control over all testing days (Fig. 3).

On day two after spawning, C. natans larvae were uniformly distributed across both halves of the control channel (MI = 0.47 ± 0.072; Fig. 3a). Larvae exposed to 2 × Sr2+, 2 × Ca2+, and CCA showed significant responses compared to control (p < 0.05). Larvae were attracted to both 2 × Sr2+ and 2 × Ca2+ (MI = 0.604 ± 0.072 and 0.502 ± 0.078, respectively). The strongest attraction observed on this day was elicited by CCA (MI = 0.762 ± 0.090).

On day four after spawning, C. natans larvae were again uniformly distributed across both halves of the control channel (MI = 0.519 ± 0.09; Fig. 3b). Larvae exposed to 50× Sr2+, 10× Ca2+, 50× Ca2+, and CCA showed significant responses compared to control (p < 0.05). Larvae were attracted to both 10× and 50× Ca2+ (MI = 0.604 ± 0.093 and 0.605 ± 0.059, respectively). Larvae were repulsed by 50× Sr2+ (MI = 0.454 ± 0.087). The strongest attraction observed on this day was also elicited by CCA (MI = 0.724 ± 0.129).

On day six after spawning, C. natans larvae were again uniformly distributed across both halves of the control channel (MI = 0.489 ± 0.073; Fig. 3c). Larvae exposed to 50× Sr2+, 10× Mg2+, and 50× Ca2+ showed significant responses compared to control (p < 0.05). Larvae were repulsed by both 50× Sr2+ and 10× Mg2+ (0.447 ± 0.076 and 0.435 ± 0.115, respectively). Interestingly, the strongest attraction observed on this day was elicited by 50× Ca2+ (MI = 0.724 ± 0.129), in contrast to previous days where CCA induced the strongest attraction.

The larval responses to various ion concentrations exhibited age-dependent variations as well as by concentration, reflected by changes in their MI with age (Fig. 3f). For C. natans, MI values for the control channels consistently remained around 0.5, indicating a nearly uniform distribution of larvae. Repulsion to 10× Mg2+ was consistent with age, with the lowest MI (0.435 ± 0.115) observed on day 6 (p < 0.05 only on day 6). In comparison, 50× Sr2+ showed increasing repulsion with age, with a minimum MI of 0.447 ± 0.076 recorded on day 6 (p < 0.05 on days 4 and 6). In contrast, 50× Ca2+ exhibited a progressively stronger attraction, peaking at an MI of 0.724 ± 0.129 on day 6 (p < 0.05 on days 4 and 6). CCA consistently elicited positive responses, with the highest MI (0.762 \(\pm\) 0.090) observed on day 2 (p < 0.05 for days 2 and 4), declining to 0.52 ± 0.125 by day 8 (p > 0.05 for days 6 and 8). The CCA, 10× and 50× calcium treatments consistently elicited attraction (Tables S1, S2, S3 and S4). Magnesium treatments (10× Mg2+ and 2 × Mg2+) resulted in repulsion, with 2 × Mg2+ responses not statistically significant. Strontium responses were concentration-dependent, with lower concentrations eliciting attraction and the highest concentration (50× Sr2+) resulting in repulsion.

These responses differed between species. On day two after spawning, O. faveolata larvae were uniformly distributed across both halves of the control channel (0.538 \(\pm\) 0.069; Fig. 3e). Larvae exposed to 10× Sr2+, 10× Mg2+, 2 × Ca2+, and CCA showed significant responses compared to control (p < 0.05). Larvae were attracted to both 10× Sr2+ and 2 × Ca2+ (MI = 0.545 ± 0.095 and 0.542 \(\pm\) 0.064, respectively). Larvae were repulsed by 10× Mg2+ (MI = 0.502 ± 0.090). The strongest attraction observed on this day was elicited by CCA (MI = 0.731 ± 0.152).

On day four after spawning, O. faveolata larvae were uniformly distributed across both halves of the control channel (0.508 \(\pm\) 0.123; Fig. 3f). Larvae exposed to 10× Sr2+, 10× Ca2+, and CCA showed significant responses compared to control (p < 0.05). Larvae were attracted to both 10× Sr2+ and 10× Ca2+ (MI = 0.549 ± 0.090 and 0.548 \(\pm\) 0.076, respectively). The strongest attraction observed on this day was elicited by CCA (MI = 0.818 \(\pm\) 0.124).

With the exception of the CCA treatments, C. natans larvae consistently exhibited greater mean MI shifts relative to the control across all chemical types and concentrations compared to O. faveolata larvae. Consequently, the subsequent findings reported here focus on C. natans. The chemicals 50× Ca, 10× Mg, and CCA elicited the largest and most statistically significant larval responses as determined by MI, thus they are the focus of the following analyses.

Effect of chemical cues on larval swimming speeds

In addition to attracting C. natans larvae, the chemical cues used here also altered their swimming speeds. To examine changes in behaviors, swimming speed and location were quantified from the trajectories of individual larvae in the experiments above, using the 10× Mg2+, 50× Ca2+, CCA, and control treatments at 5, 15, and 30 min (Fig. 4). 10× Mg2+ and 50× Ca2+ were used here as representative chemical concentrations as they elicited the strongest repulsive and attractive responses among the inorganic cues tested. CCA treatments were also examined in detail because larval accumulation patterns were distinct from those in the 50× Ca2+ treatments.

Chemical cues affect coral larval swimming speed. Time-varying and position-dependent swimming speeds of C. natans larvae exposed to 10× Mg2+ (a–c), 50× Ca2+ (d–f), and crustose coralline algae exudates (CCA) (g–i). From left to right, panels show data for 5, 15, and 30 min after chemical injection. The chemical cues were injected on the left side of the channels. (a) Average speed as a function of position for the channel with 10× Mg2+. (b) Location of larvae and their swimming speeds for the channel with 10× Mg2+. (c) Normalized position frequency distribution of larvae in 10× Mg2+. (d) Average speed as a function of position for the channel with 50× Ca2+. (e) Location of larvae and their swimming speeds for the channel with 50× Ca2+. (f) Normalized position frequency distribution of larvae for the channel with 50× Ca2+. (g) Average speed as a function of position for the channel with CCA. (h) Location of larvae and their swimming speeds for the channel with CCA. (i) Normalized position frequency distribution of larvae for the channel with CCA.

In the 10× Mg2+ treatments, larvae in the center of the channels swam faster than in the controls while larvae at the ends of the channels swam slower. After five min of exposure to Mg2+, mean larval speeds reached a maximum of 1.36 mm/s in the half of the channel where the Mg2+ was injected (Fig. 4a, left). Larval speeds near the opposite end of the channels matched the control speeds, with a maximum 3.3% difference. Larvae were evenly distributed in the channels, with slower larvae at each end and near the walls, and faster larvae in the center (Fig. 4b, left). The position frequency distribution revealed that the high speeds in the channel centers and slower speeds at the ends caused larvae to spend more time at the ends of the channels in the Mg2+ treatment than they did in the control (Fig. 4c, left). At the peak response after 15 min, mean larval speeds were higher on the side of chemical injection with a maximum speed of 2.16 mm/s (Fig. 4a, center). There was a depletion of larvae at the injection end of the channel and more larvae were observed swimming slowly at the other end, away from the Mg2+ injection site (Fig. 4b, center). These slow larvae spent much more time at the non-injection wall than the control larvae, and fewer fast larvae on the injection side meant less time was spent at that end than in the control treatments (Fig. 4c, center). Even after 30 min, larval speeds in the center of the channels remained higher than in the controls (Fig. 4a, right). There were still slow swimming larvae at each end of the channels, and higher speeds in the center with low speeds at the ends meant that larvae still spent more time at the end walls than in the control case (Fig. 4b,c, right). Throughout the 30 min, the mean speeds at the walls at each end of the channels were lower than in the center and similar to in the control, but the distribution of these slow swimming larvae differed.

When exposed to 50× Ca2+, larvae decreased their swimming speed in the high concentration regions, then increased speeds again as the Ca2+ diffused and the concentration near the injection point decreased. After five min at the peak response for 50× Ca2+, larval speeds on the injection side of the channels were slower than in the controls with a mean of 0.16 mm/s at a distance of 20 mm from the channel ends (Fig. 4d, left). Most larvae within the first 15 mm of the channel swam slower than 0.5 mm/s, while those further from the point of chemical injection swam at speeds similar to those in the controls (Fig. 4e, left). This slowdown of larvae near the injection site caused larvae to spend much more time in the high chemical regions (Fig. 4f, left). After 15 min, larvae were still swimming more slowly than in the controls on the side of the channel where the Ca2+ was injected, but the mean speed increased to 0.31 mm/s 20 mm in the channels (Fig. 4d, center). As the Ca2+ continued to diffuse and its concentration decreased at the injection site, larvae were less affected and there were faster swimming larvae on the injection sides of the channels (Fig. 4e, center). The slow swimming larvae still cause larvae to spend more time on the chemical injection side overall, but the size of the high frequency region was smaller than at five min (Fig. 4f, center). After 30 min, larval speeds across most of the channel were slightly lower than the control speeds (Fig. 4d, right). As the concentration decreased over time at the injection site, Ca2+ had less of an effect and there were slow swimming larvae more evenly distributed at each end of the channels and faster swimming larvae in the center (Fig. 4e, right). Larvae still spent more time at the injection ends of the channels, but there was also a higher frequency of larvae at the other end of the channels (Fig. 4f, right). Larvae slowed down when exposed to 50× Ca2+. However, as Ca2+ diffused through the channels over time and the concentration decreased at the injection site, larvae returned to their control speeds and distribution.

In CCA treatments, larvae slowed down when exposed and maintained reduced speeds over time. Five min after the CCA cue was injected, larvae on the injection sides of the channels swam slower than corresponding control larvae, while those on the opposite sides, away from the chemical, matched control speeds. (Fig. 4g, left). Most of the larvae swam slowly near the CCA injection site, with only a few observed swimming normally elsewhere in the channels (Fig. 4h, left). The slow speed of larvae near the CCA on the injection sides meant that larvae spent most of their time at those ends of the channels (Fig. 4i, left). After 15 min, the average speed of larvae in the channel was slower and the slow-speed region extended further into the channel, with larvae having an average speed of only 0.27 mm/s at a distance of 25 mm into the channel (Fig. 4g, center). Almost all of the larvae were affected by the CCA treatment and, unlike the response to 50× Ca2+, they did not cluster only near the injection side wall, but also spread out, moving slowly up to the halfway point of the channel (Fig. 4h, center). Because the slow larvae spread out into the channels, this also increased the size of the region in which larvae spent most of their time, encompassing the whole injection side of the channels (Fig. 4i, center). At 30 min, larvae across the entire channel swam slowly, with a maximum average speed of 0.45 mm/s (Fig. 4g, right). Most larvae continued to be affected by the CCA, predominantly remaining in the halves of the channels where the chemical was injected (Fig. 4h, right). Overall, exposure to CCA caused a persistent slowdown in larval movement throughout the 30-min observation period.

Effect of chemical cues on the straightness of larval trajectories

In this study, coral larvae also responded to chemical cues with a change in their swimming trajectories. Colpophyllia natans larvae changed the straightness of their swimming trajectories when exposed to 50× Ca2+ and to CCA (maximum responses on day six and four, respectively). However, compared to their swimming trajectories in the control channel, very little change was observed when larvae were exposed to 10× Mg2+. These changes were quantified by characterizing the tortuosity of individual larval trajectories, with higher values indicating more turning and lower values indicating straight swimming. Analysis of tortuosity values computed for 30 individual trajectories for 10× Mg2+, 50× Ca2+, and CCA, along with the control, highlight the differences in the swimming behavior of larvae (Fig. 5a).

Chemical cues affect tortuosity of coral larval swimming behavior. Individual swimming trajectories of C. natans coral larvae exposed to different chemical cues. (a) Tortuosities for 30 individual trajectories in channels containing 10× Mg2+, 50× Ca2+, and crustose coralline algae exudates (CCA), compared with the control. Example trajectories in (b) the control channel, (c) with 10× Mg2+, (d) with 50× Ca2+, (e) and with CCA.

For the control (four days after spawning), the mean tortuosity was 1.45 ± 0.15. The larvae were generally straight swimmers that occasionally reflected off the channel walls (Fig. 5b). For 10× Mg2+, the mean tortuosity was 1.20 ± 0.03. As in the control channel, the larvae generally swam in straight lines and occasionally slowed down and reflected off the walls (Fig. 5c). However, the slightly lower value of tortuosity compared to that of control indicates that the larvae turned less often in 10× Mg2+ than they did in the control. For 50× Ca2+, the mean tortuosity was 3.59 ± 0.86. In the regions away from the chemical injection ends, the larvae mostly swam in straight lines at the normal swimming speed. However, when they slowed down near the chemical injection ends of the channel, they had more curved trajectories (Fig. 5d). The higher value of tortuosity compared to that of the control indicates that the larvae turned more in 50× Ca2+. This turning behavior was localized in the chemical injection half of the channel (Figs. S4–S7). For CCA, the mean tortuosity was 6.27 ± 0.63. The larvae swam in curved trajectories at a low speed (Fig. 5e). Unlike with 50× Ca2+, these slower and curved trajectories were observed throughout the channel, rather than being confined to the chemical injection half. Larvae maintained this slow speed and increased turning behavior even after exiting the chemical-enriched region in the channel.

Effect of chemical cues on larval shape

Another type of larval response to chemical cues was a change in shape (length and width; Fig. 6a). Colpophyllia natans larvae changed shape when exposed to 50× Ca2+, with a maximum response 6 days after spawning, and in response to CCA, with a maximum response four days after spawning. Lengths and widths are reported as mean ± SE. Larvae in control channels were elliptical, with an initial mean length of 0.46 ± 0.01 mm and mean width of 0.25 ± 0.01 mm for four-day old larvae and mean length of 0.47 ± 0.01 mm and width of 0.25 ± 0.01 mm for six-day old larvae (Fig. 6b). Larval shape in the control remained constant over the 30-min trials, ranging from 0.46 ± 0.01 to 0.41 ± 0.01 mm in length and 0.25 ± 0.01 to 0.22 ± 0.01 mm in width for day four and 0.47 ± 0.01 to 0.45 ± 0.01 mm in length and 0.26 ± 0.01 to 0.25 ± 0.01 mm in width for day six (Fig. 6e,f).

Chemical cues change coral larval morphology. Chemoattractant-induced size and shape changes in C. natans larvae. (a) Schematic defining larval length (circles) and width (squares). Composite images showing nine representative coral larvae photographed in different chemotaxis treatments: (b) the control channel (day 4), (c) 5 min after 50× Ca2+ is injected (day 6), and (d) 15 min after crustose coralline algae exudates (CCA) are introduced (day 4). (e,f) Variation in the length and width of larvae as a function of time in (e) the control and 50× Ca2+ channels on day 6 and (f) the control and CCA channels on day 4.

When exposed to 50× Ca2+, larvae quickly shrank in length and then returned back close to their initial shape over time. For the maximum 50× Ca2+ response six days after spawning, larvae had a similar shape to the control larvae one min after the 50× Ca2+ was introduced, with a mean length of 0.44 ± 0.02 mm and width of 0.24 ± 0.01 mm. Five min after 50× Ca2+ was added, larvae exposed to the chemical shrank in length and became more circular (Fig. 6c). This shrinking decreased the mean length to 0.32 ± 0.01 mm, however the mean width of the larvae only slightly increased to 0.26 ± 0.01 mm and was the same width as the control larvae (Fig. 6e). Over the next 10 min as the 50× Ca2+ diffused in the channel and the local concentration decreased, larvae enlarged to be closer to their initial length, increasing the mean length to 0.38 ± 0.01 mm 15 min after the chemical was added. After 30 min, the mean length remained at 0.39 ± 0.01 mm and the mean width was 0.25 ± 0.01 mm. Interestingly, the mean width of the larvae exposed to 50× Ca2+ remained the same as the control larvae throughout the 30-min trials, even with up to a 27.5% difference in mean larval length.

Larvae showed a different shape response when exposed to CCA compared to Ca2+, increasing in length instead of shortening. One min after CCA is introduced, larvae had a mean length of 0.40 ± 0.01 mm and a mean width of 0.23 ± 0.01 mm. The larvae exposed to CCA lengthened over time, reaching a maximum length of 0.62 ± 0.01 mm 15 min after the chemical was introduced (Fig. 6d,f). The larvae also became thinner, with a mean width of 0.20 ± 0.01 mm compared to the control width of 0.23 ± 0.01 mm at the same time in the experiment. Unlike the 50× Ca2+ response with larvae changing back towards their initial shape, larvae exposed to CCA remained long and thin throughout the rest of the 30-min trial, with a final mean length of 0.60 ± 0.01 mm and width of 0.19 ± 0.01 mm.

Discussion

Effect of chemical cues on attraction

In this study, we investigated the response of swimming planula larvae from the coral species C. natans and O. faveolata to the chemical cues Ca2+, Mg2+, Sr2+, and organic exudates from crustose coralline algae (CCA). For C. natans, CCA consistently elicited strong attraction, with the response diminishing with larval age. Calcium treatments showed a concentration-dependent effect, with higher concentrations inducing stronger attraction, especially in older larvae. 50× Ca2⁺ elicited responses comparable to or stronger than CCA. Strontium elicited responses that were concentration-dependent, with lower concentrations generally attracting larvae, while higher concentrations led to consistent repulsion. Magnesium treatments typically resulted in repulsion, with stronger effects observed at higher concentrations. For O. faveolata, CCA consistently produced the strongest degree of attraction across all days of observation. Calcium treatments cause larval attraction, while strontium responses shifted from mild repulsion to moderate attraction with age at lower concentrations and remained neutral at higher concentrations. Magnesium treatments showed minimal effects on O. faveolata and were largely neutral. Overall, both C. natans and O. faveolata displayed behavioral responses to these chemical cues, but each species responded differently depend on treatment and concentration, highlighting species-specific differences in chemotactic responses.

The role of CCA as a promoter of settlement and metamorphosis in coral larvae has been extensively studied1,6,33,34. In contrast, the role of inorganic ions like Ca2+, Sr2+, and Mg2+ have not been studied as considerably, despite their importance in settlement and calcification. One previous study conducted using the brooding coral Pocillopora damicornis found that \({\text{CaCl}}_{2}\) is a highly effective inducer of larval settlement in this species23. The authors showed that increasing the concentration of \({\text{CaCl}}_{2}\) led to an increase in the number of settled larvae until the concentration reached 40 mM, after which settlement began to decline. This trend is interesting when compared to the observations made in the current study, in which increasing \({\text{CaCl}}_{2}\) concentrations generally caused more larvae to accumulate near the chemical injection point of the microfluidic channels. Perhaps \({\text{CaCl}}_{2}\) causes larvae to accumulate near the substrate which in turn leads to increased settlement. The previous study used a solution at a constant concentration, while the current study employed a time-varying gradient with higher overall starting concentration that diffused through the channels and decreased in concentration over time. Because the larval distribution in the current study reverted to a uniform distribution towards the end of the observation periods, and larvae recovered their initial shape, we conclude that the effect of Ca2+ is noticeable only when the concentration exceeds a certain threshold. Several studies have indicated that intracellular calcium homeostasis and \({\text{Ca}}^{2 + }\) ion binding proteins play a role in regulating the settlement and metamorphosis of invertebrate larvae57,58,59,60. However, the exact mechanism behind this attraction behavior to calcium in coral larvae is not known and needs to be further investigated.

A recent study also explored the effects of dissolved inorganic cues in natural hydraulic lime (NHL) substrates on coral larval settlement19. The addition of \({\text{MgCO}}_{3}\) and \({\text{SrCO}}_{3}\) to NHL substrates was found to increase settlement rates in the species C. natans and D. labyrinthiformis. These substrates, which release ions such as Mg2⁺, Sr2⁺, and Ca2⁺, demonstrate the potential of ion-releasing materials as tools to enhance coral recruitment. The study also determined that magnesium and strontium ions at 1.5× the concentration of seawater were not harmful to C. natans larvae. In the current study, the responses induced by both Mg2+ and Sr2+ at the investigated concentrations were variable. This variability underscores the need for additional research to determine the conditions under which Mg and Sr concentrations might be either beneficial or harmful to coral larvae.

Although the concentrations tested in the current study were higher than naturally occurring levels, this approach was intentional to identify threshold responses in larval behavior. In marine environments, chemical signals are rapidly diluted by dynamic, oscillatory flows, resulting in high concentrations being localized near substrate surfaces27,61,62. For artificial substrates that release ions to be effective in real-world restoration scenarios, elevated starting concentrations may be necessary. While initial concentrations may be high, the diffused chemicals are quickly advected, creating localized gradients that larvae can potentially detect even without direct contact with the substrate. These findings underscore the potential of engineered substrates to create targeted microenvironments that support coral recruitment by accumulating larvae near the surface.

Modifications to swimming speeds and trajectories

In the C. natans larvae that we focused on, there were changes in swimming speeds and the straightness of trajectories in response to different chemical cues. In the presence of Mg2+, larvae exhibited increased swimming speeds closer to the chemical injection point compared to in control conditions, and their speeds were similar to those in control conditions in regions farther from the injection site. The overall turning behavior of the larvae was slightly reduced in the presence of Mg2+, suggesting that larvae tend to swim straighter when under its influence. These behaviors contributed to the lower concentration of larvae observed near the Mg2+ injection point.

Conversely, exposure to Ca2+ resulted in decreased swimming speeds near the injection point compared to in the control, with speeds normalizing further away from the point of injection. Notably, an increase in turning behavior was observed near the injection point after exposure to Ca2+. Exposure to CCA exudates also slowed larval swimming speeds near the point of chemical injection while matching the control speeds away from the point of injection. The turning behavior was more pronounced compared to the control and, unlike with Ca2+, this increased turning was observed throughout the entire channel, not just near the injection point. These behaviors contribute to the observed larval accumulation near the injection points of Ca2+ and CCA.

Although both Ca2+ and CCA led to slower swimming speeds and increased turning behavior in the larvae, the persistence of these behaviors away from the injection point in the CCA treatments alone suggests that CCA had a more prolonged impact on larval behavior compared to Ca2+. CCA is a very complex organic cue with many different components, compared to just Ca2+, which could all contribute together to the observed larval behavior or affect the larvae at different times. The difference could also be due to different sensing and response mechanisms for organic and inorganic chemicals. The observed changes in swimming speeds and turning behaviors among the larvae could reflect an adaptive strategy to either thoroughly explore or swiftly evade their environment when they encounter a stimulus.

The effect of various inorganic ions on the swimming behavior of ciliary and flagellar organisms has been a topic of interest in other studies63,64,65. Previous studies examined the impact of magnesium and calcium ions on the gills of Mytilus edulis, documenting that \({\text{MgC}}{\text{l}}_{2}\) significantly enhances ciliary movement, whereas \({\text{CaC}}{\text{l}}_{2}\) tends to inhibit it64,65. Another study explored the influence of calcium, magnesium, and strontium ions on Arenicola, an annelid worm with ciliated larva63. In that study, magnesium induced active ciliary motion, whereas both calcium and strontium halted ciliary movement. A recent study by members of our group explored the effects of dissolved inorganic cues in NHL substrates on coral larval settlement rate in the coral species C. natans, O. faveolata, and D. labyrinthiformis19. This study reported an increased proportion of motile larvae for C. natans in the presence of \({\text{MgC}}{\text{O}}_{3}\). The findings in the current study are consistent with the effects observed with magnesium and calcium in various other ciliated organisms.

The effects of chemical cues on larval swimming speeds and behavior are critical to understanding the transport and settlement of coral larvae. Coral larvae are weak swimmers and thus experience flow speeds in natural reef environments that are significantly higher than their own swimming speeds66. Away from the substrate, they are primarily transported by bulk flows and must navigate through a variety of chemical and physical signals, including time-varying chemical gradients and flow patterns created by the reef structures61,67,68. However, near the reef surface, where flow speeds are low, larval swimming behavior becomes more important69,70. The relative swimming speed of larvae compared to the background flow determines their ability to cross transport barriers and contact the substrate21,71. Faster swimming larvae may cross transport boundaries more effectively, improving their chances of reaching settlement zones.

Many coral larvae are lecithotrophic, relying heavily on lipid energy reserves during their pelagic phase, making swimming energetically costly72. Ecologically, larval swimming is directly tied to their ability to search for a final place of settlement10,49. Owing to the limited studies on swimming changes in response to chemical cues in coral larvae, chemotactic strategies observed in other marine organisms offer useful comparisons for understanding coral larval behavior. Marine copepods, for instance, employ a combination of straight swimming and turning to locate food patches, adjusting their swimming patterns based on chemical and hydrodynamic cues73,74. Similarly, bacteria use run-and-tumble behavior to balance exploration and exploitation of chemical gradients, optimizing their position relative to attractants75,76. These strategies, although observed in different taxa and scales, offer insights into the chemotactic behaviors of coral larvae. For coral larvae, slower swimming speeds and increased turning near attractive cues like CCA and calcium may represent an area-restricted search strategy, allowing thorough exploration of potential settlement zones once they reach the substrate. Conversely, faster and more directed swimming in response to repellents, such as high magnesium concentrations, could indicate a stress or escape response to avoid adverse environments, while potentially facilitating transport to more favorable conditions26. In ecotoxicology studies, reduced swimming speeds is often associated with stress responses77,78,79. However, the observed combination of slower swimming and turning behavior in response to cues like CCA and calcium in this study suggests that reduced speeds may in certain situations represent a deliberate process of exploration; this is consistent with observations of coral larvae elongating and slowly crawling across CCA surfaces immediately prior to settlement5,80.

Modifications to larval shape

Morphological changes such as shape and size changes in response to chemical cues were also notable in C. natans larvae. Upon exposure to 50× Ca2+, the typically elliptical larvae were observed to assume a more circular shape. In contrast, exposure to crustose coralline algae (CCA) resulted in an increase in the length of the larvae and an overall transformation to a more rod-like shape. It is understood that near the reef substrate, larvae must navigate complex flow structures before settling61,71. The aspect ratio and shape of micro-swimmers play a critical role in their interaction with the surrounding flow81,82,83,84.

Studies have shown that elongated swimmers (with a high aspect ratio) have an advantage in aligning more effectively with the flow, facilitating faster and more efficient transport compared to spherical swimmers, which struggle to align and are less effectively transported81,83,84. For coral larvae, elongation may enhance their ability to align with bulk flow, facilitating more efficient transport to substrates. Conversely, smaller, more spherical larvae may benefit from their shape by accessing sheltered regions near the substrate. As observed in this study, larval size can change by up to two times in response to different cues, with a length ratio for CCA to calcium as high as 2. These size changes influence larval interactions with their environment; smaller larvae experience lower local flow speeds within the boundary layer, which could potentially enhance their retention near the substrate. The morphological changes observed in this study may represent adaptations for different stages of larval settlement, with elongation facilitating transport in bulk flow and smaller, spherical shapes supporting settlement in more protected regions.

In addition to the hydrodynamic effects of these observed changes, the observed alterations in larval shape may also represent the initial stages of metamorphosis, including the transition from water column navigation to surface crawling, probing, and attachment. Coral larvae have been observed to elongate with increasing age, and when exposed to CCA or CCA extracts, a morphology that increases contact area while allowing surface exploration5,80,85. In the transition from crawling to attachment, larvae are observed flattening into discs, enhancing their ability to attach to suitable substrates and micro textures, marking the first steps toward permanent attachment and settlement1,7,34,86. Importantly, when observed morphological changes in coral larvae are extreme, this may reflect underlying physiological processes regulated by specific binding proteins that under normal conditions contribute to successful settlement, but which may be overwhelmed in atypical or stressful chemical environments; this complex system of interactions can certainly be investigated further37,57.

Chemotaxis analysis plays a critical role in understanding how coral larvae respond to specific chemical cues, specifically when they react, the strength of their response, and the mechanisms underlying their behavior. Using our findings, artificial substrates can be designed to release ions that trigger specific swimming or morphological changes in larvae, while incorporating topological features that larvae prefer20,87,88,89. Additionally, such substrates can be engineered to generate flow structures that aid in transporting larvae toward the substrate, enhancing settlement21. Another study has shown that these substrates could further support post-settlement survival and calcification by releasing essential ions, offering a comprehensive approach to promoting coral recruitment and reef restoration19. Ultimately, this approach enhances the effectiveness of artificial reef structures in accelerating coral restoration and supporting reef ecosystems.

Conclusion

In this study, we observed diverse chemotactic responses of coral larvae to the chemical cues Ca2+, Mg2+, Sr2+, and CCA exudates, along with changes in swimming speed, swimming tortuosity, and larval morphology, demonstrating the complexity of larval sensory and behavioral responses to environmental conditions. By identifying the conditions that promote larval transport, settlement, and survival, such as optimal ion concentrations and favorable flow conditions, coral reef restoration efforts can be better tailored to enhance the recruitment and survival of coral larvae. Additionally, the insights gained from these studies can inform the design of artificial substrates that mimic natural cues and conditions, which would further support coral reef restoration initiatives.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Heyward, A. J. & Negri, A. P. Natural inducers for coral larval metamorphosis. Coral Reefs 18(3), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003380050193 (1999).

Negri, A., Webster, N., Hill, R. & Heyward, A. Metamorphosis of broadcast spawning corals in response to bacteria isolated from crustose algae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 223, 121–131. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps223121 (2001).

Huang, S. & Hadfield, M. Composition and density of bacterial biofilms determine larval settlement of the polychaete Hydroides elegans. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 260, 161–172. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps260161 (2003).

Webster, N. S. et al. Metamorphosis of a Scleractinian coral in response to microbial biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70(2), 1213–1221. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.2.1213-1221.2004 (2004).

Ritson-Williams, R., Paul, V. J., Arnold, S. N. & Steneck, R. S. Larval settlement preferences and post-settlement survival of the threatened Caribbean corals Acropora palmata and A. cervicornis. Coral Reefs 29(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-009-0555-z (2010).

Morse, D. E., Hooker, N., Morse, A. N. C. & Jensen, R. A. Control of larval metamorphosis and recruitment in sympatric agariciid corals. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 116(3), 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(88)90027-5 (1988).

Tebben, J. et al. Induction of larval metamorphosis of the coral Acropora millepora by tetrabromopyrrole isolated from a Pseudoalteromonas bacterium. PLoS ONE 6(4), e19082. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019082 (2011).

Sneed, J. M., Sharp, K. H., Ritchie, K. B. & Paul, V. J. The chemical cue tetrabromopyrrole from a biofilm bacterium induces settlement of multiple Caribbean corals. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 281(1786), 20133086. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.3086 (2014).

Gómez-Lemos, L. A., Doropoulos, C., Bayraktarov, E. & Diaz-Pulido, G. Coralline algal metabolites induce settlement and mediate the inductive effect of epiphytic microbes on coral larvae. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 17557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35206-9 (2018).

Vermeij, M. J. A., Marhaver, K. L., Huijbers, C. M., Nagelkerken, I. & Simpson, S. D. Coral larvae move toward reef sounds. PLoS ONE 5(5), e10660. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010660 (2010).

Mason, B., Beard, M. & Miller, M. W. Coral larvae settle at a higher frequency on red surfaces. Coral Reefs 30(3), 667–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-011-0739-1 (2011).

Sakai, Y. et al. A step-down photophobic response in coral larvae: Implications for the light-dependent distribution of the common reef coral, Acropora tenuis. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 17680. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74649-x (2020).

Carl, C. et al. Enhancing the settlement and attachment strength of pediveligers of Mytilus galloprovincialis bychanging surface wettability and microtopography. Biofouling 28(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927014.2012.662676 (2012).

França, F. M. et al. Climatic and local stressor interactions threaten tropical forests and coral reefs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 375(1794), 20190116. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0116 (2020).

Carpenter, K. E. et al. One-third of reef-building corals face elevated extinction risk from climate change and local impacts. Science (1979) 321(5888), 560–563. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1159196 (2008).

Hernández-Delgado, E. A. et al. Stronger hurricanes and climate change in the Caribbean Sea: Threats to the sustainability of endangered coral species. Sustainability 16(4), 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16041506 (2024).

Suzuki, G. et al. Enhancing coral larval supply and seedling production using a special bundle collection system ‘coral larval cradle’ for large-scale coral restoration. Restor. Ecol. 28(5), 1172–1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13178 (2020).

dela Cruz, D. W. & Harrison, P. L. Enhancing coral recruitment through assisted mass settlement of cultured coral larvae. PLoS ONE 15(11), e0242847. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242847 (2020).

Yus, J. et al. Composite substrates for coral larval settlement and reef restoration based on natural hydraulic lime and inorganic strontium and magnesium compounds. Ecol. Eng. 202, 107236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2024.107236 (2024).

Levenstein, M. A. et al. Composite substrates reveal inorganic material cues for coral larval settlement. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10(12), 3960–3971. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c08313 (2022).

Levenstein, M. A. et al. Millimeter-scale topography facilitates coral larval settlement in wave-driven oscillatory flow. PLoS ONE 17(9), e0274088. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274088 (2022).

Hagedorn, M. et al. Trehalose is a chemical attractant in the establishment of coral symbiosis. PLoS ONE 10(1), e0117087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117087 (2015).

Yang, Q. et al. Promoting larval settlement of coral Pocillopora damicornis by calcium. Coral Reefs 41(1), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-021-02216-5 (2022).

Gleason, D. F., Edmunds, P. J. & Gates, R. D. Ultraviolet radiation effects on the behavior and recruitment of larvae from the reef coral Porites astreoides. Mar. Biol. 148(3), 503–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-005-0098-y (2006).

Stake, J. L. & Sammarco, P. W. Effects of pressure on swimming behavior in planula larvae of the coral Porites astreoides (Cnidaria, Scleractinia). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 288(2), 181–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0981(03)00018-2 (2003).

Vermeij, M., Fogarty, N. & Miller, M. Pelagic conditions affect larval behavior, survival, and settlement patterns in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 310, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps310119 (2006).

Hadfield, M. G. & Koehl, M. A. R. Rapid behavioral responses of an invertebrate larva to dissolved settlement cue. Biol. Bull. 207(1), 28–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1543626 (2004).

Díaz-Gil, C. et al. Anthropogenic chemical cues can alter the swimming behaviour of juvenile stages of a temperate fish. Mar. Environ. Res. 125, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2016.11.009 (2017).

Harvey, E. L., Jeong, H. J. & Menden-Deuer, S. Avoidance and attraction: Chemical cues influence predator–prey interactions of planktonic protists. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58(4), 1176–1184. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2013.58.4.1176 (2013).

Tamburri, M. N., Finelli, C. M., Wethey, D. S. & Zimmer-Faust, R. K. Chemical induction of larval settlement behavior in flow. Biol. Bull. 191(3), 367–373. https://doi.org/10.2307/1543009 (1996).

Robinson, E., Lunt, J., Marshall, C. & Smee, D. Eastern oysters Crassostrea virginica deter crab predators by altering their morphology in response to crab cues. Aquat. Biol. 20(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.3354/ab00549 (2014).

Díaz-Gil, C. et al. Reversible morphological changes in a juvenile marine fish after exposure to predatory alarm cues. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7(5), 191945. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.191945 (2020).

Whitman, T. N., Negri, A. P., Bourne, D. G. & Randall, C. J. Settlement of larvae from four families of corals in response to a crustose coralline alga and its biochemical morphogens. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 16397. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73103-2 (2020).

Tebben, J. et al. Chemical mediation of coral larval settlement by crustose coralline algae. Sci. Rep. 5(1), 10803. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10803 (2015).

Whalen, K. E. et al. The chemical cue tetrabromopyrrole induces rapid cellular stress and mortality in phytoplankton. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 15498. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33945-3 (2018).

Morse, D. E. & Morse, A. N. C. Enzymatic characterization of the morphogen recognized by Agaricia humilis (Scleractinian Coral) larvae. Biol. Bull. 181(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/1542493 (1991).

Reyes-Bermudez, A., Lin, Z., Hayward, D. C., Miller, D. J. & Ball, E. E. Differential expression of three galaxin-related genes during settlement and metamorphosis in the scleractinian coral Acropora millepora. BMC Evol. Biol. 9(1), 178. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-9-178 (2009).

He, X., Wang, J., Abdoli, L. & Li, H. Mg2+/Ca2+ promotes the adhesion of marine bacteria and algae and enhances following biofilm formation in artificial seawater. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 146, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.06.029 (2016).

Reynaud, S. et al. Light and temperature effects on Sr/Ca and Mg/Ca ratios in the scleractinian coral Acropora sp. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71(2), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2006.09.009 (2007).

Mitsuguchi, T., Uchida, T., Matsumoto, E., Isdale, P. J. & Kawana, T. Variations in Mg/Ca, Na/Ca, and Sr/Ca ratios of coral skeletons with chemical treatments: Implications for carbonate geochemistry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65(17), 2865–2874. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00626-3 (2001).

Giri, S. J., Swart, P. K. & Devlin, Q. B. The effect of changing seawater Ca and Mg concentrations upon the distribution coefficients of Mg and Sr in the skeletons of the scleractinian coral Pocillopora damicornis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 222, 535–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2017.11.011 (2018).

Weinbauer, M. G., Brandstätter, F. & Velimirov, B. On the potential use of magnesium and strontium concentrations as ecological indicators in the calcite skeleton of the red coral (Corallium rubrum). Mar. Biol. 137(5–6), 801–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002270000432 (2000).

Ahmed, T., Shimizu, T. S. & Stocker, R. Microfluidics for bacterial chemotaxis. Integr. Biol. 2(11–12), 604. https://doi.org/10.1039/c0ib00049c (2010).

Hida, H., Nishiyama, H., Sawa, S., Higashiyama, T. & Arata, H. Chemotaxis assay of plant-parasitic nematodes on a gel-filled microchannel device. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 221, 1483–1491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2015.07.081 (2015).

Geertsma, R. C., Kamermans, P., Murk, A. J. & Wijgerde, T. Real-time high resolution tracking of coral and oyster larvae. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 565, 151910. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEMBE.2023.151910 (2023).

Ritson-Williams, R., Arnold, S. N., Paul, V. J. & Steneck, R. S. Larval settlement preferences of Acropora palmata and Montastraea faveolata in response to diverse red algae. Coral Reefs 33(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-013-1113-2 (2014).

Ritson-Williams, R., Arnold, S. & Paul, V. Patterns of larval settlement preferences and post-settlement survival for seven Caribbean corals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 548, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps11688 (2016).

Chamberland, V. F., Bennett, M.-J., Doblado Speck, T., Latijnhouwers, K. R. W. & Miller, M. W. Optimizing in vitro fertilization in four Caribbean coral species. PeerJ 13, e18918. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.18918 (2025).

Marhaver, K. L., Vermeij, M. J. A., Rohwer, F. & Sandin, S. A. Janzen–Connell effects in a broadcast-spawning Caribbean coral: Distance–dependent survival of larvae and settlers. Ecology 94(1), 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1890/12-0985.1 (2013).

Marhaver, K. L., Vermeij, M. & Medina, M. M. Reproductive natural history and successful juvenile propagation of the threatened Caribbean Pillar Coral Dendrogyra cylindrus. BMC Ecol. 15(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-015-0039-7 (2015).

Chamberland, V. F., Snowden, S., Marhaver, K. L., Petersen, D. & Vermeij, M. J. A. The reproductive biology and early life ecology of a common Caribbean brain coral, Diploria labyrinthiformis (Scleractinia: Faviinae). Coral Reefs 36(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-016-1504-2 (2017).

Quinlan, Z. A. et al. Coral larval settlement induction using tissue-associated and exuded coralline algae metabolites and the identification of putative chemical cues. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 290, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.1476 (2009).

Karbalaei, A. & Cho, H. Microfluidic devices developed for and inspired by thermotaxis and chemotaxis. Micromachines 9(4), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi9040149 (2018).

Sun, X., Higgins, J. & Turchyn, A. V. Diffusive cation fluxes in deep-sea sediments and insight into the global geochemical cycles of calcium, magnesium, sodium and potassium. Mar. Geol. 373, 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.12.011 (2016).

Poisson, A. & Papaud, A. Diffusion coefficients of major ions in seawater. Mar. Chem. 13(4), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(83)90002-6 (1983).

Yuan-Hui, L. & Gregory, S. Diffusion of ions in sea water and in deep-sea sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 38(5), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(74)90145-8 (1974).

Reyes-Bermudez, A., Miller, D. J. & Sprungala, S. The Neuronal Calcium Sensor protein Acrocalcin: A potential target of calmodulin regulation during development in the coral Acropora millepora. PLoS ONE 7(12), e51689. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051689 (2012).

Chen, D. et al. Isolation of a calcium-binding peptide from tilapia scale protein hydrolysate and its calcium bioavailability in rats. J. Funct. Foods 6, 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2013.12.001 (2014).

Carafoli, E. & Krebs, J. Why Calcium? How calcium became the best communicator. J. Biol. Chem. 291(40), 20849–20857. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R116.735894 (2016).

Freeman, G. & Ridgway, E. B. The role of intracellular calcium and pH during fertilization and egg activation in the hydrozoan Phialidium. Dev. Biol. 156(1), 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1006/DBIO.1993.1068 (1993).

Koehl, M. A. R. & Hadfield, M. G. Hydrodynamics of larval settlement from a Larva’s point of view. Integr. Comp. Biol. 50(4), 539–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icq101 (2010).

Koehl, M., Strother, J., Reidenbach, M., Koseff, J. & Hadfield, M. Individual-based model of larval transport to coral reefs in turbulent, wave-driven flow: Behavioral responses to dissolved settlement inducer. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 335, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps335001 (2007).

Lillie, R. S. The relation of ions to ciliary movement. Am. J. Physiol. Legacy Content 10(7), 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplegacy.1904.10.7.419 (1904).

Gray, J. The effects of Ions upon ciliary movement. J. Cell Sci. S2–64(255), 345–371. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.s2-64.255.345 (1920).

James, G. The mechanism of ciliary movement. II.—The effect ions on the cell membrane. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Contain. Papers Biol. Character 93(650), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1922.0008 (1922).

Hata, T. et al. Coral larvae are poor swimmers and require fine-scale reef structure to settle. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 2249. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02402-y (2017).

Reidenbach, M. A., Koseff, J. R. & Monismith, S. G. Laboratory experiments of fine-scale mixing and mass transport within a coral canopy. Phys. Fluids 19(7), 075107. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2752189 (2007).

Reidenbach, M. A., Koseff, J. R., Monismith, S. G., Steinbuckc, J. V. & Genin, A. The effects of waves and morphology on mass transfer within branched reef corals. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51(2), 1134–1141. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.2.1134 (2006).

Hench, J. L. & Rosman, J. H. Observations of spatial flow patterns at the coral colony scale on a shallow reef flat. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118(3), 1142–1156. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20105 (2013).

Stocking, J. B., Rippe, J. P. & Reidenbach, M. A. Structure and dynamics of turbulent boundary layer flow over healthy and algae-covered corals. Coral Reefs 35(3), 1047–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-016-1446-8 (2016).

Larsson, A. I., Granhag, L. M. & Jonsson, P. R. Instantaneous flow structures and opportunities for larval settlement: Barnacle larvae swim to settle. PLoS ONE 11(7), e0158957. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158957 (2016).

Bennett, C. E. & Marshall, D. J. The relative energetic costs of the larval period, larval swimming and metamorphosis for the ascidian Diplosoma listerianum. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 38(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10236240400029333 (2005).

Mazzocchi, M. G. & Paffenhoefer, G.-A. Swimming and feeding behaviour of the planktonic copepod Clausocalanus furcatus. J. Plankton Res. 21(8), 1501–1518. https://doi.org/10.1093/plankt/21.8.1501 (1999).

Leising, A. W. & Franks, P. J. S. Does Acartia clausi (Copepoda: Calanoida) use an area-restricted search foraging strategy to find food?. Hydrobiologia 480(1/3), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021253622168 (2002).

Stocker, R. & Seymour, J. R. Ecology and physics of bacterial chemotaxis in the ocean. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76(4), 792–812. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00029-12 (2012).

Mittal, N., Budrene, E. O., Brenner, M. P. & van Oudenaarden, A. Motility of Escherichia coli cells in clusters formed by chemotactic aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100(23), 13259–13263. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2233626100 (2003).

Wallace, W. G. & Estephan, A. Differential susceptibility of horizontal and vertical swimming activity to cadmium exposure in a gammaridean amphipod (Gammarus lawrencianus). Aquat. Toxicol. 69(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquatox.2004.05.010 (2004).

Faimali, M. et al. Swimming speed alteration of larvae of Balanus amphitrite as a behavioural end-point for laboratory toxicological bioassays. Mar Biol 149(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-005-0209-9 (2006).

Antonio-Martínez, F. et al. Leachate effects of pelagic Sargassum spp. on larval swimming behavior of the coral Acropora palmata. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 3910. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60864-z (2020).

Grasso, L. C. et al. The biology of coral metamorphosis: Molecular responses of larvae to inducers of settlement and metamorphosis. Dev. Biol. 353(2), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.010 (2011).

Zhang, Z., Qiu, J. & Zhao, L. Micro-swimmers in vertical turbulent channel flows. Int. J. Multiphase Flow 151, 104035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2022.104035 (2022).

Qin, B. & Arratia, P. E. Confinement, chaotic transport, and trapping of active swimmers in time-periodic flows. Sci. Adv. 8(49), eadd6196. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.add6196 (2022).