Abstract

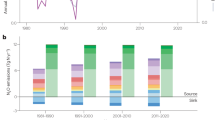

Applying biochar and using cover crops are two potential approaches to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. However, the effectiveness of these methods, individually or in combination, in salt-affected soils remains unclear. Thus, the objective was to determine the impact of barley (Hordeum vulgare) and biochar on N2O and CO2 emissions from salt-affected soil. During the 28-day replicated study, GHG emissions were measured near-continuously and the number of nirK, nirS, qnorB, and nosZ gene copies were measured 12 and 28 days after planting (DAP). Biochar accelerated barley emergence and reduced N2O–N and CO2–C emissions by 68% and 44% from 8 to 14 DAP, respectively. Barley reduced N2O–N emissions by 30.4% between 8 and 14 DAP, and at 12 DAP it reduced the number of nirK gene copies, that encodes for nitrite reductase by 40.9% and increased the number of nosZ gene copies, that encodes for nitrous oxide reductase by 193%. The biochar impact on N2O emissions was attributed to the 44% reduction in soil respiration, whereas the impact of barley was attributed to changes in the number of nirK and nosZ gene copies leading to increased efficiency of N2O reduction to N2. Overall, combining barley with biochar resulted in the greatest reduction (85%) of N2O emissions compared to soil alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rising sea levels, land use change, and climate patterns are contributing to a global increase in salt-affected soils1. The consequences of these events include high erosion rates, low crop productivity, poor soil health, and high nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions2,3. Therefore, to reduce the impact of salt-affected soils on the environment, mitigation techniques are needed.

Several mitigation approaches have been used globally to restore their productivity4. A historic approach is to install tile drainage and apply chemical amendments such as gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O)4. However, because salt-affected soils are often located over marine sediments, which provide a constant source of salts, classical approaches may have minimal success5,6. An alternative approach to mitigate the impact of salt-affected soils on the environment is to follow the soil health principles which include providing vegetative cover and maximizing the presence of living roots (also referred to as phytoremediation)7,8.

Using plants as a mitigation tool has the potential to reduce wind and water erosion and simultaneously increasing microbial biomass and reducing N2O emissions7. However, establishing plants in salt-affected soil can be problematic because many plants cannot thrive in soils with high electrical conductivities (EC).

Prior research compared the growth of barley (Hordeum vulgare), mustard (Brassica juncea) and Kernza wheat (Thinopyrum intermedium) in a highly salt-impacted South Dakota soil. Mustard and Kernza emerged and grew, but barley had superior emergence and growth8. In addition, barley reduced N2O emissions, which others have primarily attributed to plant-induced decreases in nitrate and soil moisture9. However, Clay et al.8 also attributed the decreased N2O emissions to enhanced efficiency of N2O reduction to N2. Still, they did not demonstrate that barley increased or decreased the number of gene copies linked to denitrification or quantify that there was a change in the relative amount of N2O and N2 that was produced by the microorganisms. Thus, the objectives were to determine the impact of softwood biochar and barley, alone and in combination, on N2O and CO2 emissions from salt-affected soil, as well as the impact of biochar on barley emergence and growth.

Results

Biochar impact on soil properties and barley germination

Adding 5% soft-wood biochar to the salt-affected soil increased soil organic matter (SOM) by about 5%, decreased electrical conductivity (EC1:1) by about 7%, and reduced soil NH4–N by about 50% (Table 1). However, biochar did not influence the Melich III P concentration, which was surprising because biochar often has strong P sorption capacity10.

Biochar induced decreases in EC1:1 may have contributed to 30% increase in barley seedlings emergence in the soil + biochar + barley treatment when compared to soil + barley treatment at 11 DAP11,12. Although biochar accelerated barley emergence, barley biomass 28 DAP was 46 (± 11) g m−2 in the biochar treatment and 41 (± 17) g m−2 in the no-biochar treatment. In addition to reducing EC, the application of biochar increased the soil water content 12 and 28 DAP (Table 2).

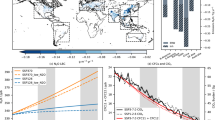

Nitrous oxide emissions

From 0 to 7 DAP, which corresponded to the period prior to seedling emergence, N2O emissions were slightly higher in the soil + barley than soil alone treatment or soil + biochar treatments (Table 3, Fig. 1). From 8 to 14 DAP, adding biochar to the soil reduced N2O emissions 68% (Table 3, Fig. 1). These results were attributed to the biochar reducing soil microbial respiration by 44% (as shown by reduced CO2 emissions), which reduced oxygen consumption and the risk of denitrification. From 8 to 14 DAP, the biochar + barley treatment reduced N2O emissions by 84% compared to biochar treatment, and the barley treatment reduced emissions by 31% as compared to soil alone treatment. The comparison of the biochar and barley treatments suggests that the combination of treatments was synergistic. Relative to the soil treatment, the soil + biochar treatment had higher soil moisture content, while the soil and soil + barley treatments had similar soil moisture contents 12 DAP (Table 2). These results indicate that the reduction in N2O emissions from 8 to 14 DAP were not directly attributed to plant-induced decreases in soil moisture. For the 22 to 28 DAP period, the only treatment that reduced N2O emissions was the soil + barley + biochar treatment.

Biochar reduced CO2 emissions from the 0 to 7 and from the 8 to 14 DAP periods (Table 3). The factor(s) responsible for reduced respiration was not determined, however others have reported that reduced respiration may be related to biochar sorption of dissolved organic C13.

Soil microbial biomass and 16S rRNA, qnorB, nirK, nirS, and clade I nosZ copies

At 12 DAP, total microbial biomass was similar across treatments with an average of 17.6 µg C g−1 soil. Barley with and without biochar 28 DAP did not influence microbial biomass, whereas microbial biomass was 25% lower in the soil with biochar than the soil without biochar (see Supplementary Table 1 online). At 12 DAP, biochar and barley did not influence Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), and from 12 to 28 DAP AMF remained constant and were not influenced by biochar or barley.

The biochar and barley treatments had a mixed impact on 16S rRNA, qnorB, nirK, nirS, and clade I nosZ gene copies (Table 4). For example, 12 DAP biochar did not influence the number of nirK and nosZ gene copies, however, barley reduced the number of nirK and increased the number of nosZ gene copies (Table 4). The bacterial gene, 16S rRNA, was non-significant across treatments. At 12 DAP, barley reduced the number of nirK gene copies, while at 28 DAP barley increased the number of nosZ gene copies.

Relationship between the measured values

From 8 to 14 DAP, the strong relationship between 16SrRNA and N2O emissions suggests that bacteria were actively involved in N2O emissions. However, the correlation analysis also showed that the number of nirK (r = 0.58) genes copies were positively correlated to N2O emissions between 8 and 14 DAP (p = 0.097) (Table 5). This correlation was important because the nirK gene encodes for nitrite reductase that catalyzes the reduction of \({\text{NO}}_{2}^{ - }\) to NO in denitrification. The gene qnorB that encodes for nitric oxide reductase, which catalyzes the reduction of NO to N2O, was not correlated to N2O emissions but was correlated to CO2 emissions. The positive relationship between nirK and N2O emissions and negative relationship between nosZ and N2O emissions may partially explain why barley reduced N2O emissions. For the 8–14 DAP period, soil water content (SWC) was negatively correlated (p < 0.05) to N2O emissions, which suggests that N2O emissions decreased with increasing soil water. These results were attributed to biochar increasing SWC and reducing N2O emissions.

Across treatments, CO2 was not correlated to N2O emissions from 8 to 14 DAP. This was unexpected and suggested that the biochar treatment may have confounded this relationship. When the soil and soil + biochar treatments were separated, relationships differed for the soil and soil + biochar treatments (Fig. 2). Others have shown that biochar-induced decreases in CO2 emissions may be associated with biochar sorption of dissolved organic C13.

Consistent correlations between the measured values across the sampling period were not observed. For example, 16S rRNA (r = 0.96) was positively correlated to N2O emissions from 8 to 14 DAP and negatively correlated from 22 to 28 DAP (Table 5). In a second example, from 8 to 14 DAP, nirK was positively correlated to N2O and negatively correlated to N2O from 22 to 28 DAP. These results suggest the mechanisms impacting N2O emissions changed during the study. One of the differences may have been a decrease in the biochar effectiveness with time14 (Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

This study showed that adding biochar to this salt-affected soil improved barley emergence. The accelerated emergence was attributed to reductions in EC1:1 which in turn would reduce oxidative stress (Table 1)15,16,17,18,19. Despite the positive effect of biochar to barley emergence, it had a minimal effect on the number 16S rRNA, qnorB, nirK, nirS, and clade I nosZ gene copies. These results suggest that the mechanism responsible for the biochar and barley reductions in N2O emissions differed.

Nitrous oxide is an important greenhouse gas that is produced during nitrification and denitrification20. However, our recent study using near-continuous GHG measurement systems suggested that salt-affected soil emissions may be twice what is observed in productive soil8. This high risk of emissions in salt-affected soils may be linked to poor plant growth, resulting in high nitrate concentrations and a high number of nitrite reductase, nirS, gene copies that encodes for the nitrite reductase gene2.

The emission of N2O from the soil alone treatment was greater than from the soil + barley treatment. Several studies9,20,21 have shown that soil water content and pore space are key drivers to N2O emissions; however, our current results showed that factors other than soil water content also affect emissions. For example, the gravimetric soil moisture content at 12 DAP were similar in the soil and soil + barley treatments (Table 2). These findings were different than other studies who reported that plant-induced decreases in N2O emissions can be attributed to reduced soil moisture (water filled pore space) and inorganic N22,23. While water filled pore space is important, our results showed that plants induced changes in the number of nirK and nosZ gene copies may also have reduced nitrate subject to denitrification and increased efficiency24 that N2O is reduced to N2 (Fig. 3). Barley increasing the nirK gene copies and reducing the nosZ gene copies were important because nirK encodes for nitrite reductase, which catalyzes one of the first steps of denitrification and nosZ encodes for nitrous oxide reductase, which catalyzes the reduction of N2O to N2. This is a key finding and helps explain the results of others25. However, additional work is needed to more clearly define these interactions and potential solutions for decreasing emissions.

Soil microbial dynamics reflected temporal changes in microbial activity that could be influenced by several factors including nutrients, and root exudates. The N-cycling genes could be driven by different pathways depending on known and unknown factors. For example, nirK-type communities can thrive in oxygen limited conditions whereas nirS-type communities are more sensitive to environmental changes28.

In addition, biochar reduced N2O and CO2 emissions. These results were attributed to biochar reducing EC, and sorbing soluble organics. However, the impact on N2O emissions decreased with time. Others have reported that biochar impacts GHG emissions by influencing the soil physical, biological, and chemical properties22,29,30. In addition, Sun, et al.31 reported that biochar can increase soil carbon storage while reducing CO2 emissions. Our results did not show significant change in the salt concentrations, except Mg++, across treatments. However, further research on the influence of salt concentrations could help better understand the mechanisms of N2O and CO2 emissions from salt-affected soils.

Conclusions

Our study confirmed that barley can effectively grow in salt-affected soils, showing significant emergence and biomass production even at high salinity levels (EC1:1 > 10 dS m−1). Nitrous oxide emissions were higher in no-plant soil compared to soil with barley or biochar treatments. The reduced emissions were attributed to the influence of plants and biochar on soil properties and microbial activities. Specifically, the abundance of nirK and nosZ gene copies varied across treatments. Barley and biochar affected these genes differently, with no-plant soil having higher nirK gene copies and lower nosZ copies than the barley treatment. Biochar reduced soil respiration, which attributed to biochar sorbing dissolved organic carbon13.

The findings from this study suggested that integrating salt-tolerant plants like barley and biochar into saline–sodic soils can mitigate the negative impacts of salinity, enhance plant growth, and reduce GHG emissions. This approach provides needed information for the management of salt-affected soils. Future research should explore the long-term effects of these treatments and their broader implications for soil health and climate change mitigation.

Materials and methods

Experimental details

The saline/sodic soil used in the experiment was a Cresbard-Cavour loam (fine, smectitic, frigid, Calcic Natrudoll)29. The soil had EC1:1 and %Na greater than 2 dS m−1 and 4%, respectively, which categorized the soil as a saline/sodic based on DeSutter et al.32. Bulk soil from 0 to 15 cm depth was collected from the field, mixed, and stored at 4 °C until the experiment was initiated. Previous studies conducted at this site were Fiedler et al.2, Clay et al.8, Fiedler et al.29 and Clay et al.33. The biochar used in this experiment was manufactured from Southern Yellow Pine (Pinus echinata Mill.) using a continuous flow pyrolysis system to heat the feedstock to > 700 °C in a low oxygen environment. This biochar was selected because Arinaitwe34 reported that softwood biochar was superior to hard wood biochar at increasing seed germination. Barley seeds used in this study were obtained from a local vendor (Renovo seed, Brookings, SD, USA).

The experiment was arranged in a completely randomized design with four treatments and three replications (dftotal = 11). The four treatments were soil, soil + biochar, soil + barley, and soil + biochar + barley. The biochar treatments were prepared by mixing 5% biochar by weight with 3000 g of field moist soil. No additional nutrients were applied.

The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse following Clay et al.8. The study was conducted in the greenhouse as early-stage research to test if barley could be used as a nurse crop in salt-affected fields, while minimizing GHG emissions, in a cost effective manner. Biochar was included as a treatment because of its anions and cations sorption potential, thereby reducing soil electrical conductivity35,36,37,38,39. Barley (Hordeum vulgare) was selected because our previous results8 showed that it outperformed mustard (Brassica juncea) and Kernza (Thinopyrum intermedium) in reducing N2O emissions40.

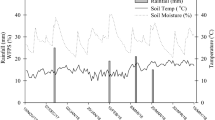

In this experiment, approximately 3000 g of the field-moist soil or soil + biochar was packed into a 20-cm diameter by 15-cm deep polyvinyl chloride (PVC) cylinder rings, filling them to a soil depth of approximately 7 cm to mimic a field bulk density of 1.37 g cm−3. The rings were placed over PVC mesh that were placed on a plastic tray. Sixty barley seeds per PVC ring were planted at a depth of 0.5-cm. The experiment was initiated on February 12, 2024, and terminated on March 11, 2024. The 28-day duration allowed adequate time to capture the peak emissions8 during the early germination phase of plants and balanced the need for data collection with the constraints of GHG measurement system. From planting to emergence, approximately 200 mL of water was added every third day, and from emergence to termination, 200 mL of water was added to chambers every other day. Seed emergence was measured daily.

Greenhouse gases measurement

The greenhouse gases (GHG) were measured following Joshi et al.7 using a LI-COR long-term opaque chamber (8200 LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). The measurement system mixed air within the chamber (volume 4244 cm3 when closed), and measured water vapor, CO2, and N2O every second for two minutes every hour using the trace gas analyzer LI-COR 7810 (CO2 and H2O) and LI-COR 7820 (N2O) (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Fluxes were determined using the LI-COR SoilFluxPro v5.3 software and the accuracy of the factory calibration was checked with standard gases at the beginning and end of the experiment. The daily cumulative CO2–C and N2O–N emissions were summed to determine emissions for the 0–7, 8–14, 15–21, and 22–28 days after planting (DAP). Soil water contents and soil temperatures were measured for the 0–5 cm depth when gas samples were collected and analyzed.

Samples collection and measurements

Soil samples were collected at 0, 12 and 28 DAP. For samples collected at 12 and 28 DAP 200 ml of water was applied 1 day prior to collecting the samples. These samples were analyzed for gravimetric soil water content. For samples collected at 0 and 28 DAP, soil EC1:1 and soil nutrients were determined following Nathan and Gelderman41 (Ward Laboratories Inc., Kearney, NE). Although the EC measurement from saturated paste is recommended42, EC1:1 (soil-to-water ratio is 1:1) has been commonly measured across similar studies8,33 and has been described as a less expensive and an efficient way to measure and compare relative changes in salinity across treatments. The initial soil samples had EC1:1, NO3–N, NH4–N, SO4–S, Cl−, %Na, and CECa value of 10.38 dS m−1, 78 mg NO3–N kg−1, 7.2 NH4–N mg kg−1, 7.9 g SO4–S kg−1, 187 mg Cl kg−1, 30.3% Na, and 69 cmolc kg−1, respectively. Based on previous research the %Na and the sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) values are similar43. Soil samples collected at 12 and 28 DAP were also analyzed for gravimetric soil water and microbial analyses following Nathan and Gelderman41 and White et al.44, respectively. For the barley treatments, the soil samples were collected from the rhizosphere. Soil organic matter (SOM) was measured using the weight loss on ignition method, which is reported to have high correlation with dry combustion method45.

Plant shoot biomass clipped after termination was measured for fresh weight and then dried at 60 °C until constant weight and ground for mineral content analysis (Ward Laboratories Inc., Kearney, NE). Plant fresh root biomass was measured after carefully washing the soil attached to the roots and dried at 60 °C to obtain dry biomass. The dried plant samples were analyzed for macro- and micronutrients by a commercial laboratory (Ward Laboratories Inc., Kearney, NE, USA).

Analyses of 16S rRNA, qnorB, nirK, nirS, and clade I nosZ copies

Soil DNA was extracted from 0.5 g of fresh soil that was collected at 12 and 28 DAP using the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (Cat. No. 116560200, MP Biomedicals) following the standard kit protocol2. The concentration of the eluted DNA was measured using the Nanodrop Microvolume UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the samples were stored at − 20 °C until analysis.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis was conducted following Fiedler et al.2. In this analysis, the number of 16S rRNA, qnorB, nirK, nirS, and clade I nosZ copies were determined46,47. The 16S rRNA provides an index for the bacterial domain48,49,50, whereas the nirK and nirS genes encode for the nitrite reductase enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of nitrite to nitric oxide. The qnorB gene encodes for nitric oxide reductase that catalyzes the reduction of NO to N2O51, and the bacterial gene nosZ encodes for nitrous oxide reductase that catalyzes the reduction of N2O to N252. For qPCR analysis, standards (see Supplementary Table 1 online) and primers (see Supplementary Table 1 online) were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies. The concentration of the extracted DNA samples was standardized to 20 ηg µL−1 following the manual (Pub. No. MAN0018825, https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/MAN0018825_PowerTrackSYBRGreenMasterMix_UG.pdf) provided with PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific)2. The qPCR reaction was conducted in 20 µL volume, and the total volume contained a 10 µL aliquot of the SYBR Green Master Mix, 8 µL of ddH2O, 0.5 µL of both forward and reverse primers (8000 ηM concentration), and 1 µL of the template DNA.

Soil microbial biomass analysis

Soil microbial biomass was determined using phospholipid fatty acid analysis2,8 following Buyer and Sasser53. Extracts were analyzed using a Shimadzu GC-2010 plus gas chromatograph (Shimadzu Corporation, Japan). A standard was used to calibrate the gas chromatograph before and after 11 samples, and the extracted fatty acids were characterized into different microbial communities using the Sherlock Software (Biolog, Inc., Hayward, CA).

Data analysis

Plants, soils, GHG emissions, and number of gene copies were analyzed using ANOVA test using base R programming (v4.3.1) and upon significant treatment difference, the least significant difference mean separation was conducted using the “agricolae” package. The output of a normal Q–Q plot was used to determine the normality. The GHG measurements were separated into four 7-day periods, 0–7, 8–14, 15–21, and 22–28 days after planting with day 0–7 representing a period before seedling emergence. Most of the seedlings emerged during days 8–14; therefore, days 15–21 and 22–28 represent the periods of seedling growth. The 95% confidence intervals for many of the measured values are provided. Unless noted, significant differences are reported at the 5% level. Correlation across the different genes copy numbers, cumulative N2O and CO2 at 8–14 and 22–28 DAP periods, and soil water content were calculated using the inbuilt ‘cor’ function in R.

Data availability

The dataset generated during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Clay, D. E., DeSutter, T. M., Clay, S. A. & Nleya, T. Salinity and Sodicity: A Growing Global Challenge to Food Security, Environmental Quality and Soil Resilience (Wiley, 2024).

Fiedler, D. J. et al. CO2 and N2O emissions and microbial community structure from fields that include salt-affected soils. J. Environ. Qual. 50, 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20223 (2021).

Eggleston, H., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T. & Tanabe, K. 2006 IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) for the IPCC https://www.ipcc.ch/report/2006-ipcc-guidelines-for-national-greenhouse-gas-inventories/ (2006).

Clay, D. E., Pandit, S. & Bhattarai, D. Case studies on salt-affected soil remediation. In Salinity and Sodicity: A Growing Global Challenge to Food Security, Environmental Quality and Soil Resilience (eds. Clay, D.E., DeSutter, T.M., Clay, S.A. & Nleya, T.) 129–142 (Wiley, 2024).

Budak, M. et al. Increased rainfall may place saline/sodic soils on the tipping point of sustainability. J. Soil Water Conserv. 77, 418–425 (2022).

Birru, G. A. et al. Chemical amendments of dryland saline–sodic soils did not enhance productivity and soil health in fields without effective drainage. Agron. J. 111, 496–508 (2019).

Joshi, D. R. et al. Quantification and machine learning based N2O–N and CO2–C emissions predictions from a decomposing rye cover crop. Agron. J. 116, 795–809 (2024).

Clay, S. A. et al. Plants reduced nitrous oxide emissions from a Northern Great Plains saline/sodic soil. Agron. J. 116, 1343–1356 (2024).

Linn, D. M. & Doran, J. W. Effect of water-filled pore space on carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide production in tilled and nontilled soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 48, 1267–1272. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1984.03615995004800060013x (1984).

Chintala, R. et al. Phosphorus sorption and availability from biochars and soil/B iochar mixtures. CLEAN Soil Air Water 42, 626–634 (2014).

Das, S. K., Ghosh, G. K. & Avasthe, R. Evaluating biomas-derived biochar on seed germination and early seedling growth of maize and black gram. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 12, 1–14 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Biochar addition reduces salinity in salt-affected soils with no impact on soil pH: A meta-analysis. Geoderma 443, 116845 (2024).

Chang, J. et al. Corn stover biochar reduced N2O and CO2 emissions in soil with different water filled pore spaces and diurnal temperature cycles. Agron. J 108, 2214–2221 (2016).

Coleman, B. S. L., Easton, Z. M. & Bock, E. M. Biochar fails to enhance nutrient removal in woodchip bioreactor columns following saturation. J. Environ. Manag. 232, 490–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.11.074 (2019).

Sultan, H. et al. Biochar and nano biochar: Enhancing salt resilience in plants and soil while mitigating greenhouse gas emissions: A comprehensive review. J. Environ. Manag. 355, 120448 (2024).

Lehmann, J., Czimczik, C., Laird, D. & Sohi, S. Biochar for Environmental Management 215–238 (Routledge, 2012).

Huang, K. et al. Soil acidification and salinity: The importance of biochar application to agricultural soils. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1206820 (2023).

Kim, H.-S. et al. Effect of biochar on reclaimed tidal land soil properties and maize (Zea mays L.) response. Chemosphere 142, 153–159 (2016).

Akhtar, S. S., Andersen, M. N., Naveed, M., Zahir, Z. A. & Liu, F. Interactive effect of biochar and plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes on ameliorating salinity stress in maize. Funct. Plant Biol. 42, 770–781 (2015).

Bateman, E. J. & Baggs, E. M. Contributions of nitrification and denitrification to N2O emissions from soils at different water-filled pore space. Biol. Fertility Soils 41, 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-005-0858-3 (2005).

Wang, H. et al. Quantifying nitrous oxide production rates from nitrification and denitrification under various moisture conditions in agricultural soils: Laboratory study and literature synthesis. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1110151. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1110151 (2023).

Zhang, A. et al. Effect of biochar amendment on yield and methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a rice paddy from Tai Lake plain, China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 139, 469–475 (2010).

Kennedy, T., Decock, C. & Six, J. Assessing drivers of N2O production in California tomato cropping systems. Sci. Total Environ. 465, 36–47 (2013).

Hiis, E. G. et al. Unlocking bacterial potential to reduce farmland N2O emissions. Nature 630, 1–8 (2024).

Joshi, D. R. et al. A global meta-analysis of cover crop response on soil carbon storage within a corn production system. Agronomy J. 115, 1543–1556 (2023).

Wrage-Mönnig, N. et al. The role of nitrifier denitrification in the production of nitrous oxide revisited. Soil Biol. Biochem. 123, A3–A16 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Functional potential of soil microbial communities in the maize rhizosphere. PLoS ONE 9, e112609 (2014).

Ming, Y. et al. Insights into the evolutionary and ecological adaption strategies of nirS-and nirK-type denitrifying communities. Mol. Ecology 33, e17507 (2024).

Fiedler, D. et al. Phytoremediation and high rainfall combine to improve soil and plant health in a North America Northern Great Plains saline sodic soil. J. Soil Water Conserv. 77, 381–388 (2022).

Cheng, L. et al. Biochar produced at high temperature mitigates NO emission and promotes nitrogen retention in subtropical forest soils. GCB Bioenergy 16, e13132. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.13132 (2024).

Sun, N. et al. Biochar addition increased soil carbon storage but did not exacerbate soil carbon emission in young subtropical plantation forest. Forests 15, 917 (2024).

DeSutter, T. M., Clay, D. E., Oster, J., Westhoff, S. & Alvarez-Torres, B. Laboratory methods for determining salinity and sodicity. In Salinity and Sodicity: A Growing Global Challenge to Food Security, Environmental Quality and Soil Resilience (eds. Clay, D.E., DeSutter, T.M., Clay, S.A. & Nleya, T.) 31–40 (Wiley, 2024).

Clay, S. A., Fiedler, D., Reese, C. & Clay, D. E. Restoring ecological function to saline–sodic soils in South Dakota with perennial grass mixtures. Agronomy J. 115, 135–146 (2023).

Arinaitwe, U. Evaluating Canola Genotypes for Growth and Yield Under Different Environmental Conditions in South Dakota (South Dakota State University, 2021).

Akhtar, S. S., Andersen, M. N. & Liu, F. Biochar mitigates salinity stress in potato. J. Agronomy Crop Sci. 201, 368–378 (2015).

Zhang, Y., Ding, J., Wang, H., Su, L. & Zhao, C. Biochar addition alleviate the negative effects of drought and salinity stress on soybean productivity and water use efficiency. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 1–11 (2020).

Lee, X. et al. Use of biochar to manage soil salts and water: Effects and mechanisms. Catena 211, 106018 (2022).

Rahi, A. A. et al. Toxicity of Cadmium and nickel in the context of applied activated carbon biochar for improvement in soil fertility. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29, 743–750 (2022).

Dawar, K. et al. Biochar and urease inhibitor mitigate NH3 and N2O emissions and improve wheat yield in a urea fertilized alkaline soil. Sci. Rep. 11, 17413 (2021).

Basche, A. D., Miguez, F. E., Kaspar, T. C. & Castellano, M. J. Do cover crops increase or decrease nitrous oxide emissions? A meta-analysis. J. Soil and Water Conserv. 69, 471–482 (2014).

Nathan, M. & Gelderman, R. Recommended Chemical Soil Test Procedures for the North Central Region (Univ. of Missouri, 2012).

Datta, A., Mandal, A. & Yadav, R. Proper measurement of electrical conductivity and other parameters influence profile salinity and sodicity under different land uses. Ecol. Indicators 101, 1004–1006 (2019).

DeSutter, T. et al. Relating sodium percentage to sodium adsorption ratio and its utility in the northern Great Plains. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 79, 1261–1264 (2015).

White, L. J., Brözel, V. S. & Subramanian, S. Isolation of rhizosphere bacterial communities from soil. Bio-protocol 5, e1569–e1569 (2015).

Roper, W. R., Robarge, W. P., Osmond, D. L. & Heitman, J. L. Comparing four methods of measuring soil organic matter in North Carolina soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 83, 466–474 (2019).

Braker, G., Zhou, J., Wu, L., Devol, A. H. & Tiedje, J. M. Nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) as functional markers to investigate diversity of denitrifying bacteria in Pacific Northwest marine sediment communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2096–2104 (2000).

Zumft, W. G. & Körner, H. Biology of the Nitrogen Cycle 67–81 (Elsevier, 2007).

Church, D. L. et al. Performance and application of 16S rRNA gene cycle sequencing for routine identification of bacteria in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33, e00053. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00053-19 (2020).

Bartoš, O., Chmel, M. & Swierczková, I. The overlooked evolutionary dynamics of 16S rRNA revises its role as the “gold standard” for bacterial species identification. Sci. Rep. 14, 9067 (2024).

Angnes, G. et al. Correlating denitrifying catabolic genes with N2O and N2 emissions from swine slurry composting. Bioresour. Technol. 140, 368–375 (2013).

Braker, G. & Tiedje, J. M. Nitric oxide reductase (norB) genes from pure cultures and environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 3476–3483 (2003).

Orellana, L. et al. Detecting nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) genes in soil metagenomes: Method development and implications for the nitrogen cycle. MBio 5, e01193. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01193-14 (2014).

Buyer, J. S. & Sasser, M. High throughput phospholipid fatty acid analysis of soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 61, 127–130 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This paper was partially funded by U.S. Department of Agriculture, under Agreement Number NR233A750004G076, South Dakota State University, USDA-NRCS-CIG (NR233A750011G019), American Coalition for Ethanol, GEVO, SD Corn Utilization Councill. The qPCR equipment was supported in part by NSF/EPSCoR Grant No. 0091948 and the State of South Dakota and is part of the SDSU-Functional Genomics Core Facility (FGCF). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In addition, any reference to specific brands or types of products or services does not constitute or imply an endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for those products or services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.B. performed the investigation, data curation, formal analysis, wrote the original draft, and reviewed and edited the draft; S.P., and R.K. performed the investigation, samples collection, data collection, and reviewed the draft; T.N., D.E.C., and S.A.C. conceptualized, supervised, validated the study, and reviewed and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhattarai, D., Pandit, S., Kafle, R. et al. Synergistic effects of biochar and plants can reduce greenhouse gas emissions from salt affected soil. Sci Rep 15, 8879 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93198-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93198-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spatial assessment, mapping, and characterization of salt-affected soils in Uttar Pradesh state of the Gangetic plain (IGP), India, for planning reclamation and management

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)