Abstract

In this study we investigated the effect that lumbar decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) has on sagittal balance and its clinical significance. This was an observational cohort study for LSS cases treated with decompression surgery. Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI), EuroQoL (EQ-5D) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) were used preoperatively and at 1 year follow-up. Pelvic incidence (PI), pelvic tilt (PT), sagittal vertical axis (SVA) and lumbar lordosis (LL) were measured before and 1 year after surgery. Hierarchical clustering (HC) was performed to identify subgroups with distinct patterns of variation. Ninety-five patients were included, mean age of 63 years, with good/excellent outcome in 71.6%. The median difference between postoperative and preoperative LL was − 1.3o. Increased lumbar lordosis was correlated to ODI improvement (Pearson, r=-0.33). Three clusters were identified after HC. Patients in cluster 2 (31.6% ) had decrease in LL after surgery (mean values for cluster 1, 2, 3: 3.3o, -5.6o, 0.8o), increase in SVA (-5 mm, + 25 mm, -19 mm) and no improvement in ODI (-23.1, 3.77, -17.1). Lumbar decompression has little effect in lumbar lordosis and sagittal balance. Cluster analysis yielded a subgroup of patients with worse outcomes, associated to decrease of LL and increase of SVA after surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a common degenerative lumbar disease. It is characterized by a progressive decrease in the anatomical size of the lumbar spine canal and is associated with symptoms that result in a decrease in quality of life. It is the most common cause of lumbar surgery in individuals over 65 years of age1.

As age advances, a sequence of static anatomical changes occur in the lumbar spine, namely, loss of disk height associated with mechanical incompetence of the disk, hypertrophy of the facet joints and ligamentum flavum, bone remodeling and atrophy of the extensor muscles2. These changes lead to a loss of lumbar lordosis, which can cause some degree of positive sagittal imbalance. Compensatory mechanisms are associated with degenerative changes, attempting to maintain an upright posture with minimal effort and the sagittal alignment. These mechanisms include thoracic kyphosis reduction, retrolisthesis, pelvis retroversion, knee flexion and ankle extension2.

The sagittal balance of the body is defined by spinopelvic parameters, including pelvic incidence (PI), pelvic tilt (PT), sacral slope (SS), sagittal vertical axis (SVA) and lumbar lordosis (LL). Changes in these parameters, namely a positive SVA, are related to a greater severity of symptoms and represent indicators of worse quality of life3. These parameters should be considered when making the surgical decision for a patient with LSS4. However, the exact relationship between the changes in spinopelvic parameters and the outcomes after decompression surgery is not yet defined.

In a previous study, we demonstrated that preoperative spinopelvic parameters are not decisive in predicting the clinical outcomes of patients with LSS without significant sagittal imbalance who undergo decompressive procedures. Preoperative SVA, RLL (Relative Lumbar Lordosis) and RPT (Relative Pelvic Tilt) were not associated with achievement of clinical threshold for functional improvement after surgery5.

Degenerative LSS, in addition to the static degenerative modifications, also has a dynamic component. In fact, trunk flexion and axial distraction lead to the widening of the spinal canal. This postural change results in an decrease in lumbar lordosis, which allows for a relieve of the symptoms and an increase in walking distance6. As a result, patients tend to adopt a forward-bending posture with flexion of the hips and knees that, if prolonged over time, leads to decreased strength and atrophy of the paraspinal muscles7. Therefore, it is possible that some patients with lumbar spinal stenosis have decreased lordosis to enlarge the spinal canal for clinical relief, and sagittal balance parameters can be modified in these patients after decompression5.

Thus, the aim of this study is to determine the effect that lumbar decompression surgery has on spinopelvic parameters, based on radiological findings, and whether these changes after surgery are related to clinical results.

Methods

Study design

This observational registry-based (Spine Tango) cohort study included patients with lumbar spinal stenosis who underwent lumbar decompressive procedures in the spine unit of a neurosurgical department of a Portuguese university hospital, from January 2017 to December 2019. The study protocol was approved by hospital’s ethics committee, all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Patients gave consent to be enrolled in the registry and STROBE guidelines were followed for writing.

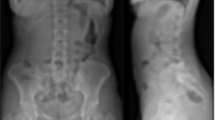

Inclusion criteria were patients over 18 years of age, who underwent decompressive procedures for lumbar spinal stenosis, had a pre and postoperative lateral full-length spine X-ray, a pre and postoperative questionnaire for clinical outcome assessment and had a follow-up clinical assessment of at least 1 year after surgery. Exclusion criteria were patients who underwent a discectomy or lumbar fusion at the same operative time, patients with previous lumbar fusion, patients with Baastrup’s disease, presence of synovial facet cysts or patients with non-degenerative spine pathology. The operative procedures are standardized in our center, with uni or bilateral interlaminar approach with flavectomy and laminotomy or partial medial facetectomy, as needed. Bilateral approaches spare the posterior midline structures, unilateral approaches include driling of the base of the spinous process for over the top decompression.

Clinical data

The following clinical and demographic parameters were collected from the medical records: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), current smoker status, approach, number of levels, complications, outcome defined by the Odom criteria.

The Spine Tango registry was accessed to collect Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) before and 1 year after surgery. The Core Outcome Measures Index for the back (COMI), EuroQoL Five Dimension Questionnaire (EQ-5D) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) questionnaires were used for pre and postoperative assessment.

All the questionnaires were self-completed by the patients or by phone by a researcher not involved in the patient clinical follow-up.

Radiological parameters

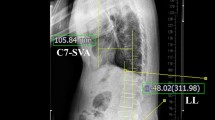

To evaluate the sagittal alignment the following spinopelvic parameters were used: pelvic incidence (PI), pelvic tilt (PT), sacral slope (SS), sagittal vertical axis (SVA), L1–S1 lordosis (LL), L4–S1 lordosis and the segmental lordosis of the operated segment. These parameters was measured as previously described8, in brief: PI, angle between the perpendicular to the S1 endplate passing through its center and the line connecting this point to the center of femoral heads; PT, angle between the vertical axis and the line connecting the center of S1 endplate to the center of femoral heads; SS, angle between the horizontal axis and the S1 endplate; SVA, horizontal distance between the C7 plumb line and the posterior–superior S1 corner; LL: angle between upper L1 endplate and S1 endplate; L4–S1 lordosis, angle between upper L4 endplate and S1 endplate; segmental lordosis, angle between upper endplate of cranial vertebra and lower endplate of caudal vertebra regarding surgical levels of decompression. These parameters were measured on a lateral full-length standing spine radiograph preoperatively and at least 6 months after surgery. They were taken independently by two researchers, for data analysis the mean of each pair of measurements was considered.

To calculate the ideal spinopelvic parameters these formulas were used: ideal LL = 0.54 × PI + 27.6 and ideal PT = *0.44 × PI—11.4 8; the lumbar distribution index was calculated as L4-S1 lordosis/LL x 100 9. Relative lumbar lordosis (RLL) and relative pelvic tilt (RPT) were the result from the following subtractions: LL – ideal LL and PT-ideal PT.

The lumbar lordosis variation (postoperative LL – preoperative LL) was defined as the primary endpoint and a relevant change of 5 degrees was settled by authors’ consensus.

Statistical analysis and sample size calculation

R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) version 4.1.1 was used for data analysis.

For sample size calculation an effect size was based on 5º variation and 13º of standard deviation5 (d = 5/13), a p value of 0.05 and a power value of 0.8 were used. The calculated sample size was 110 patients, potential dropouts not taken into account.

For agreement analysis intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) estimates were calculated based on mean rating, absolute agreement, 2-way random effects model.

Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality distribution of continuous data. Variation values were obtained with subtraction of the preoperative measurements from the postoperative ones. Continuous variables were analysed with Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired data and Kruskal-Wallis were used for median comparison between independent samples. Correlation analysis was performed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient according to variables distribution. A p value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Further evaluation was planned to understand the underlying structure of the data and identify subgroups of patients with different patterns of clinical and radiological variation. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis was performed after dimension reduction with principal component analysis (PCA)10,11. PCA is an unsupervised analysis that reduces the complexity of high-dimensional data while preserving important patterns. Dimension reduction is achieved by transforming the data into a smaller set of dimensions called Principal Components. This was important for our data, with many clinical and radiological variables per patient and where multiple comparisons could be a concern. PCA was performed after scaling of continuous variables, an eigenvalue > 1 and a cumulative variance > 80% were used as criteria to select dimensions. After that, hierarchical agglomerative clustering was performed in the selected Principal Components. This algorithm employs the use of distance measures to generate clusters. We determined the number of clusters by partitioning the dendrogram to maximize the distance between nodes using the Ward’s criterion.

Results

The overall characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. A total of 95 patients were included in this study, with a mean age of 63 years and 50 (52.6%) males. One or two levels surgery was done in 93.6% of the patients, unilateral approach was used in 55.8% of the cases. The complication rate was 10.5%, consisting of dural tears without postoperative effects, one CSF leak and one infection. The outcome defined by the Odom criteria was good or excellent in 71.6% of the patients.

The mean preoperative and postoperative values for clinical scores and radiological parameters are summarized in Table 2. There were no differences between preoperative and postoperative radiological parameters, except for RLL but with a difference below 3º. For the COMI, ODI and Eq. 5D there were significant improvements in the postoperative follow-up.

Excellent reliability was achieved in inter-rater agreement analysis with ICCs ranging from 0.85 to 0.93.

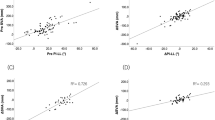

Lumbar lordosis change

The median difference between postoperative and preoperative LL was − 1.3º (Q1, Q3: -3.08, 4.85) (Fig. 1), this value was not statistically significant (signed rank test, p = 0.127. The lumbar lordosis change was correlated to functional improvement as measured with ODI (Pearson, r=-0.33, p = 0.003) (Fig. 2). There were no other clinically significant correlations between radiological changes and improvement in clinical scores (ODI, COMI and EQ-5D).

Cluster analysis and interpretation

To appreciate whether groups with distinct patterns of clinical and radiological variations could be identified, we used an unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis after PCA dimension reduction. Eight principal components were selected accounting for 83% of data variance. Hierarchical cluster analysis on these dimensions defined 3 different clusters of patients: cluster 1 with 31 patients (32.6%), cluster 2 with 30 patients (31.6%), cluster 3 with 34 patients (35.8%).

The classification according to clusters grouped patients that are closer to each other. To understand how these clusters are different, we compared clinical and radiological differences between groups with hypothesis testing.

In comparison with subjects in other clusters, patients classified in the cluster 2 showed significantly greater LL decrease (mean values for cluster 1, 2 and 3: 3.3o, -5.6o and 0.8o) and SVA increase after surgery (-5 mm, + 25 mm and − 19 mm) (Figs. 3 and 4). This was clinically relevant, as the patients in this cluster showed no improvement of the functional status, (ODI variation: -23.1, 3.77 and − 17.1) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

In view of these results, lumbar decompression surgery for spinal stenosis seems to have little or no effect on spinopelvic parameters and sagittal alignment. Although, there was a moderate correlation between increase of LL after surgery and functional improvement. Additionally, a subgroup of patients (31.6%) was identified where worse clinical results seems to be related to LL and global sagittal balance (SVA).

The importance of spinopelvic parameters in adults with spinal deformity is well studied. It is known that a positive sagittal balance has a linear relationship with symptom severity12. Additionally, it is possible to predict the surgical outcome of patients based on the SVA and the difference between the PI-LL, integrating these parameters into the therapeutic decision13,14. In LSS, no consensus has yet been reached regarding the relationship between spinopelvic parameters and clinical and surgical outcomes. In a previous study, we found out that spinopelvic parameters are not crucial in predicting the clinical outcomes of patients with LSS without significant sagittal imbalance who undergo decompressive procedures5. However, we know that in these patients the change in spinopelvic parameters occurs as a compensatory postural mechanism to avoid symptoms of neurogenic claudication15. Therefore, it is generally thought that decompression surgery may improve pelvic alignment in patients with LSS. In this study, decompression surgery has not shown potential for sagittal alignment correction. It is unlikely that an interlaminar decompression could lead to important structural changes in lumbar spine that can affect sagittal alignment. Also, according to these results the theoretical dynamic component of improvement of sagittal profile after decompression has not been confirmed or it is a small effect with no clinical relevance. Few imbalanced patients can be another reason for the absence of significant variation in radiological parameters in the current study.

Clinical significance was found in the correlation between LL improvement and ODI variation, and in the characteristics of the patients in cluster 2. Those may have importance for the understanding of the patients with poor outcome since lack of clinical improvement can be related to failure to increase LL after surgery. In cases of severe functional impairment after decompression, more aggressive surgery for lordosis restoration can be an option.

Literature review.

The current literature reports improvements of sagittal balance parameters, namely SVA and lumbar lordosis, after lumbar decompression surgery. However, this improvement is often small and not always clinically significant. Our results support this view of absence of a clinical effect regarding the entire cohort, for about one third of patients (cluster 2) negative outcomes had a relation with postoperative sagittal imbalance.

In a systematic review including 10 articles, Ogura et al.16 concluded that the rate of spontaneous correction of SVA from high to normal values ranged from 25 to 73% in the various articles. Postoperative sagittal imbalance, rather than preoperative, were more related to negative clinical outcomes. In our study, about one third of patients (cluster 2) had a relation between negative outcomes and postoperative sagittal imbalance.

In another systematic review, which looked at 18 observational studies, Hatakka et al.17 showed that there were indeed small changes in sagittal spinopelvic alignment towards a more neutral value after lumbar decompression surgery. In fact, there was an increase in LL and a decrease in PT and SVA, but the pooled effect sizes were very small (3º, -1.6º and − 9.6 mm). Risk of bias were related to different study objectives, heterogeneity on populations and decompression techniques. Our results support this view of absence of a clinical effect when we look the entire cohort.

Bouknaitir et al.18 showed a statistically significant improvement in sagittal balance in patients undergoing decompression alone for lumbar spinal stenosis. In their study, a decrease in SVA from 65 mm to 48.6 mm and in PI-LL mismatch from 7.80 to 4.2 was seen, as well as an association between a higher SVA and worse clinical outcomes as measured by the ODI and VAS for leg pain.

Salimi et al.19 concluded in a retrospective study that, after minimally invasive surgery, spinal sagittal malalignment can change to normal alignment at both short-term and long-term follow-ups. Lumbar lordosis significantly increased after decompression surgery at the 2-year (from 30.2° to 38.5) and 5-year follow-ups (to 35.7°). At the 5-year follow-up, 82.5% of patients with preoperative normal alignment maintained normal alignment, while 42.6% of patients with preoperative malalignment established normal alignment. The bigger effects of these studies were not reproduced by the present study or many previous works, further research should help to understand better this problem.

Limitations

This is a single center study, which can be a source of bias. Also, there was only one clinical and radiological evaluation for each patient in the postoperative period.

In contrast to multivariate methods, cluster analysis has the benefit of exploring and understanding the research subjects as the whole picture, the analysis involves consideration of the entire case more than comparisons between variables within each case. However, the results of this cluster analysis should be interpreted with caution, as findings from a single cohort may not generalize to other populations. External validity of these analytical approaches needs to be established through replication in further studies to ensure the robustness of the findings.

Conclusions

Lumbar decompression surgery seems to have none or little effect in spinopelvic parameters and sagittal balance. However, in this sample one cluster of patients was identified with worse outcomes, which was related to decrease of LL and increase of SVA after surgery.

Data availability

The dataset analysed during the current study and a supplemental file with the code and analysis are available at https://github.com/Pedrosantossilva/LSS_SB.

References

Deyo, R. A. et al. Trends, major medical complications, and charges associated with surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in older adults. JAMA 303, 1259–1265 (2010).

Barrey, C., Roussouly, P., Perrin, G. & Le Huec, J. C. Sagittal balance disorders in severe degenerative spine. Can we identify the compensatory mechanisms? Eur. Spine J. 20, 626–633 (2011).

Mehta, V. A., Amin, A., Omeis, I. & Gokaslan, Z. L. Gottfried, O. N. Implications of spinopelvic alignment for the spine surgeon. Neurosurgery 76, S42–S56 (2015).

Bayerl, S. H. et al. The sagittal balance does not influence the 1 year clinical outcome of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis without obvious instability after microsurgical decompression. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 40, 1014–1021 (2015).

Costa, M. A., Silva, P. S., Vaz, R. & Pereira, P. Correlation between clinical outcomes and spinopelvic parameters in patients with lumbar stenosis undergoing decompression surgery. Eur. Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06639-6 (2020).

Genevay, S. & Atlas, S. J. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 24, 253–265 (2010).

Hikata, T. et al. Impact of sagittal spinopelvic alignment on clinical outcomes after decompression surgery for lumbar spinal canal stenosis without coronal imbalance. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 23, 451–458 (2015).

Le Huec, J. C., Thompson, W., Mohsinaly, Y., Barrey, C. & Faundez, A. Sagittal balance of the spine. Eur. Spine J. 28, 1889–1905 (2019).

Yilgor, C. et al. Global alignment and proportion (GAP) score: development and validation of a new method of analyzing spinopelvic alignment to predict mechanical complications after adult spinal deformity surgery. J. Bone Joint Surg. 99, 1661–1672 (2017).

Husson, F., Josse, J. & Pagès, J. Principal component methods—hierarchical clustering—partitional clustering: why would we need to choose for vsualizing data? (2010).

Maugeri, A., Barchitta, M., Basile, G. & Agodi, A. Applying a hierarchical clustering on principal components approach to identify different patterns of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic across Italian regions. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–10 (2021).

Glassman, S. D. et al. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 30, 2024–2029 (2005).

Schwab, F. et al. Scoliosis research Society—Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: A validation study. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 37, 1077–1082 (2012).

Schwab, F., Patel, A., Ungar, B., Farcy, J. P. & Lafage, V. Adult spinal Deformity—Postoperative standing imbalance: how much can you tolerate?? An overview of key parameters in assessing alignment and planning corrective surgery. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 35, 2224–2231 (2010).

Barrey, C., Jund, J., Noseda, O. & Roussouly, P. Sagittal balance of the pelvis-spine complex and lumbar degenerative diseases. A comparative study about 85 cases. Eur. Spine J. 16, 1459–1467 (2007).

Ogura, Y., Kobayashi, Y., Shinozaki, Y. & Ogawa, J. Spontaneous correction of sagittal spinopelvic malalignment after decompression surgery without corrective fusion procedure for lumbar spinal stenosis and its impact on clinical outcomes: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Sci. 25, 379–383 (2020).

Hatakka, J., Pernaa, K., Rantakokko, J., Laaksonen, I. & Saltychev, M. Effect of lumbar laminectomy on spinal sagittal alignment: a systematic review. Eur. Spine J. 30, 2413–2426 (2021).

Bouknaitir, J. B., Carreon, L. Y., Brorson, S. & Andersen, M. 221. Change in sagittal alignment after decompression alone in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a prospective cohort study. Spine J. 20, S109–S110 (2020).

Salimi, H. et al. The effect of minimally invasive lumbar decompression surgery on sagittal spinopelvic alignment in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a 5-year follow-up study. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 1–8 https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.11.Spine201552 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: P.S.S., P.P.; Methodology: P.S.S., P.P.; Formal analysis and investigation: P.S.S., J.L.; Writing - original draft preparation: J.L., P.S.S.; Writing - review and editing: P.S.S., P.P., R.V.; Supervision: P.P., R.V.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, P.S., Leocádio, J.S.N., Vaz, R. et al. Influence of decompression surgery on sagittal balance parameters in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Sci Rep 15, 11113 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93319-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93319-4