Abstract

The grassland caterpillar is a significant pest of alpine meadows on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Its larvae primarily feed on forage grasses, resulting in financial losses. However, limited research has been done on the morphological features of larvae of this species thus far. The distribution and habitat of Gynaephora menyuanensis were extensively investigated in this instance through field study. The findings indicate that this species is primarily found in the northeast of Qinghai and parts of Gansu Province in alpine meadows at an altitude of 3,000 m. For the first time, SEM is used to report the external morphology and ultramorphology of the first and last instar larvae of G. menyuanensis, including the larval head capsule, mouthparts, antennae, sensilla, thoracic legs, prolegs, and setae. The results indicated that the larvae share similar morphological characteristics except for the number of cutting incisors and crochets. The mature instar larvae have two distinct color funnel warts (yellow and red) on abdominal segments VI and VII, distinguishing them from other lepidopteran larvae. Additionally, the chaetotaxy of the first instar larvae of G. menyuanensis was studied and described in detail, identifying seven clusters (PD, D, SD, L, SV, V, CV) on the larval trunk. This study provides a theoretical basis for the rapid identification of such pests and is beneficial for their monitoring and management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gynaephora is a small genus belonging to the Lymantriinae subfamily, primarily found in the high mountainous areas of the Northern Hemisphere and the Arctic tundra1. To date, a total of fifteen species have been described worldwide, of which eight are endemic to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP)1,2,3,4, which are known as the red head black caterpillars. Gynaephora menyuanensis Yan & Chou (1997) is the most widely distributed grassland caterpillars on the QTP with the lowest altitudes (approximately 3000 masl) and high density among the eight Gynaephora species5. It is naturally distributed primarily in the Qinghai, Tibet, and Gansu areas of China. Since the 1960s, tremendous pesticides have been applied to control these pests, which seriously impact the distribution of G. menyuanensis. Previous studies focused solely on the sampling plots in the northeastern region of the QTP (including Menyuan, Qilian, Tianjun, Gangcha and Haiyan)2,4. However, upon further investigation, we discovered that their habitats extend beyond these areas. Systematical investigation of all the primary distribution regions of G. menyuanensis is urgently needed to warn and prevent the outbreak of these grassland caterpillars.

Gynaephora menyuanensis has gained a reputation as a devastating pest that harms the ecosystem of alpine meadows and the advancement of animal husbandry2. More than 20 species of forage grasses, including Elymus nutans Griseb., Stipa capillata L., Artemisia lancea Van., Poa crymophila Keng ex C. Ling, and Krascheninnikovia ceratoides(L.) Gueldenst., are consumed by its voracious larvae, where infestations cause 20–80% loss of alpine meadows and contribute to their degeneration6. In addition, the larvae and cocoons of grassland caterpillars that remain in the meadows are poisonous to livestock and humans, causing serious skin irritations, leading to mouth sores and broken tongue disease in domestic animals7. In recent years, due to global climate change, the pest has frequently erupted and caused disasters in the alpine grasslands of the QTP, and the harm has been further aggravated.

The life history of holometabolous insects significantly influences the production and development of agriculture and forestry, especially during the larval period8. In fact, biologists draw more attention to pest larvae than the corresponding adults. Due to the high diversity of morphological characteristics among different groups, particularly in Lepidoptera, larval morphology might yield useful features for insect taxonomic and phylogenetic analyses9. In recent years, the morphological features of larvae have become more critical in the phylogenetic analysis of different holometabolic insect groups10. However, previous studies indicated that larvae of G. menyuanensis are similar to other Gynaephora species in some morphological features11. Genetic-based systems, DNA barcoding (mitochondrial DNA cytochrome c oxidase I gene, COI) would be more accurate to provide accurate species-level identification for these congeneric species with sympatric distributions12.

Grassland caterpillars can survive in the extreme environment of the QTP for a long time and become the dominant species, which must have the external morphological characteristics and corresponding survival strategies adapted to the habitat environment11. Several studies have revealed that many species have acquired morphological features to adapt to their particular environments. Previous research explored the genetic basis associated with the adaptive evolution of G. menyuanensis1. However, there is a lack of systematic research results on the morphology of grassland caterpillar larvae. Therefore, to help safeguard the fragile ecosystems, our study used external morphology and molecular technology to identify the larvae samples and determine their distribution over the Tibetan Plateau. Furthermore, we used light and scanning electron microscopy to describe the morphology and chaetotaxy of G. menyuanensis larvae for the first time, adding to the body of evidence for larval identification and illuminating the underlying defensive mechanisms of these grassland caterpillars.

Results

Identification

The morphological features described by Yan are entirely comparable to the white and orange-red markings on the abdominal intersegmental membrane of the last instar larvae of Gynaephora menyuanensis, which also have black abdominal prolegs and an anterior pectoral backplane11 (Fig. S1). Phylogenetic trees for all the samples of G. menyuanensis and the outgroup species (G. jiuzhiensis and G. minora) were constructed based on COI gene (Fig. S2). Both the ML and BI analyses indicated a similar topology. The results showed that the G. menyuanensis populations clustered into one clade. The pairwise corrected genetic distances based on COI sequences among G. menyuanensis species were shown in Table S1. There was a significant decrease in the intraspecific genetic distances of 0–0.0012 (n= 20) and the nucleotide similarity with the reference sequences of 99.8% compared to the inter-species genetic distances of 0.03 of Lepidoptera13. The individuals acquired in our study are all members of the same species, i.e., G. menyuanensis (Lepidoptera: Lymantriinae), based on molecular and morphological identifications.

Distribution and habitats

The primary distribution regions of G. menyuanensis are parts of Gansu (Minle, Sunan, and Jishishan) and the northeastern alpine meadow areas of Qinghai (Menyuan, Qilian, Haiyan, Tianjun, Gangcha, Datong, Huzhu, Ledu, Hualong, Xunhua, Tongren, Guide, Gonghe, Xinghai, Tongde, and Guinan) (Fig. 1A, B). These habitats have an average elevation of about 3,000 m, an average annual temperature of 0.6 °C, and an annual precipitation of about 530 mm (Fig. 1). In particular, around 55% of the annual precipitation falls in June, July, and August, corresponding to a typical continental plateau climate. The plant growth period spans approximately last for 135 days annually. According to our findings, G. menyuanensis was more abundant near streams and they primarily consumed high-quantity forage, including Poaceae and Cyperaceae (Fig. 1D, S3).

Morphology of the last instar larvae

The general body morphology

Gynaephora menyuanensis larvae in their last instar are usually eruciform, bearing a head, thorax, and abdomen (Fig. S1A). With three pairs of thoracic legs, four pairs of abdominal prolegs, and one pair of anal prolegs, its cylindrical trunk contains 13 segments (Fig. S1B, C). There are prominent hair tufts with dense black setae covering the dorsal surface. With a pair of prothoracic spiracles and eight pairs of abdominal spiracles on A1–A8, the respiratory system is of the peripneustic type. There is a pair of funnel warts on abdominal segments VI to VII, a hallmark of the Lymantriinae family. The abdominal intersegmental membrane of G. menyuanensis displays white and red speckles that can be used to identify it from other Gynaephora species (Fig. S1B).

The head

With an inverted Y-shaped ecdysial line on the midcranium measuring 3.519 ± 0.52 mm (n = 60) in width (Fig. 2A, B, D), the hemispherical and sclerotized head turns positive red with the increase of larva instar (Fig. 2). There are a lot of bristles on the dorsal surface of the head (Fig. 2). Six pairs of protuberant stemmata are symmetrically arranged behind the antennae (Fig. 2B, C). The antennae, which are located laterally behind the mandibles, are divided into three segments: a well-developed basal scape located in the antennal fossa, a long pedicel, and a cone-shaped, shorter flagellum at the end of the pedicel (Fig. 3A).

Light micrograph and scanning electronmicroscopy of heads of the last instar larva of G. menyuanensis. (A) Frontal view light microscopy; (B) anterior view; (C) lateral view; (D) dorsal view. an: antenna; cls: clypeus; el: ecdysial line; lbr: labrum; lp: labial palp; mn: mandible; st: stemmata; s1–s6: stemma.

Mouthparts of the last instar larva of G. menyuanensis. (A) Light micrograph of frontal view; (B) scanning electron microscopy of the frontal view; (C) clypeus and labrum; (D) left mandible; (E) maxillary palp and galea; (F) spinneret and labial palp. an: antenna; cls: clypeus; co: condyle; ga: galea; lai: labium; lbr: labrum; lp: labial palp; mn: mandible; mp: maxillary palp; mx: maxilla; sp: spinneret; T1–T4: tooth; Sp: spicule.

The mandibulate variety of mouthparts includes a labrum, a pair of mandibles, a pair of maxillae, and a labium (Fig. 3B). The clypeus, which has six pairs of setae on its external surface, is connected to the labrum, which is a flat, medially notched structure (Fig. 3C). To assist the larvae feeding on grass, the labrum can move back and forth. The paired mandibles have complementary heavy sclerotization and asymmetrical shapes (Fig. 3C). The cutting end has a pair of setae on the external surface and is wavy with four sharp ends (distal teeth) on the apical margin for shredding food (Fig. 3D). On the labium, the paired maxillae are symmetrically positioned. Each maxilla’s primary purpose, comprising a cardo, stipes, galea, and a maxillary palp, is to grasb food and facilitate chewing. The center between the paired maxillae is covered in many triangular-shaped spicules with sharp ends (Fig. 3E). A pair of labial palps and a spinneret are provided by the labium (Fig. 3F). Silk is secreted from a hole at the top of the spinneret, a cuticle-covered tubular structure that protrudes from the anterior of the labium. The mouthparts of the first instar larvae are similar to the last instar larvae except that the sclerotization of mandible, forming three incisors on the apical margin, and an immature spinneret protrudes ventrally and has less spicule (Fig. S4A).

Types of sensilla in the antenna and mouthparts

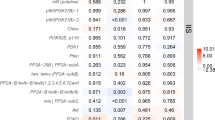

The mouthparts under SEM reveal the morphological traits of four distinct types of sensilla (Fig. 4, S5; Table 1):

Sensilla in the antenna and mouthparts of the last instar larvae of G. menyuanensis. (A) Antenna; (B) sensilla in the flagellum; (C) sensilla in the maxillae; (D) sensilla in the maxillary palp. fla: flagellum; ga: galea; mp: maxillary palp; mx: maxilla; ped: pedicel; sca: scape; Sb: sensilla basiconica; Sch: sensilla chaetica; Ss: sensilla styloconica; Str: sensilla trichodea.

Sensilla trichodea (Str, two subtypes: Str I, Str II); Sensilla chaetica (Sch, two subtypes: Sch I, Sch II); Sensilla styloconica (Ss, two subtypes: Ss I, Ss II); and Sensilla basiconica (Sb, two subtypes: Sb I, Sb II).

Located on the mouthparts of G. menyuanensis larvae in their last instar, Str are the most prevalent sensilla. With an end that resembles hair, the Str I are located near the apex of the antennal pedicle. Str II are longer than Str I and located on the surface of the maxillae and apex of the antennal pedicle (Fig. 4A; Table 1). At the midpoint, the Str II are helical.

Sch have two kinds, primarily located on the ventral side of the larval antennae: long Sch (Sch I) and short Sch (Sch II). Sch I are found near the base of the antennal flagellum and maxillary galea, and they progressively taper to the blunt tip with smooth cuticles. The Sch II are nearly perpendicular to the antennal surface and are gathered on the antennal pedicle’s surface (Fig. 4B). Sch I and Sch II have mean lengths of 39.97 ± 3.25 μm and 16.33 ± 2.23 μm, respectively, and the basal widths of 13.01 ± 3.87 μm and 6.41 ± 1.21 μm, respectively (Table 1).

Ss can be divided into two types based on their shapes. Ss I have a smooth surface without any visible wall pores at the top of the antennal flagellum and a thin and pointed cone protrusion at the blunt distal points. Ss II have a smooth surface on the maxillary galea and a blunt tip papillary protrusion (Fig. 4C). The basal widths of Ss are 12.86 ± 0.85 μm and 13.40 ± 1.76 μm, respectively, and the mean lengths are 24.60 ± 1.34 μm and 19.98 ± 2.65 μm (Table 1).

The apex of the Sb is rounded and blunt. Sb I are found on the antennal flagellum’s surface and the maxillary palp’s apex. The columnar Sb I have oblique striations and several tiny, uneven, wrinkle-shaped pores at their blunt tips and hidden sockets. Longer and more robust than Sb I, Sb II is primarily located in the maxillary basal fossa and antennal pedicel. The Sb II has sharp tips and smooth walls without detectable depressions (Fig. 4D; Table 1). The first instar larvae have the same number and types of sensilla as the mature instar larvae (Fig. S4B, C, D).

Thoracic legs and prolegs

Three thoracic legs (Fig. 5A, B), each of the thoracic leg is composed with a coxa, femur, tibia, tarsus, and pretarsus (Fig. 5C). The coxa is covered with dense hair. The femur and longest tibia have several setae on their lateral surfaces, whereas their anterior surfaces are usually glabrous. The tarsus is subconical in shape and has two short setae, five short sensilla chaetica, and a terminally curved, pointed pretarsus (Fig. 5D).

Thoracic legs and prolegs of the last instar larvae of G. menyuanensis. (A) Light micrograph of the last instar larva; (B) three pairs of thoracic legs; (C) a pair of thoracic legs; (D) pretarsus magnification; (E) abdominal prolegs; (F) anal prolegs. al: anal prolegs; cx: coxa; fe: femur; pl: prolegs; pr: pretarsus; ta: tarsus; ti: tibia; tl: thoracic legs.

The unsegmented abdominal prolegs consist of proximal and distal bases and are located on abdominal segments III and VI (Fig. 5E, S6). Several setae cover the lateral and mesal surfaces of the proximal base (Figs. 5E and 6A, S6). Mesally, the planta is covered in dense microtrichia (Fig. 6D). The apical planta of prolegs have 17–25 uniform crochets arranged in a mesal penellipse, while the first instar larvae only have four to five crochets (Fig. 6A–D, S7, S8). Except for the number of crochets, the anal and abdominal prolegs of the first instar larvae have similar structures to the last instar larvae (Fig. S8).

Setae on the trunk

The grass caterpillar larvae are covered by dense hair tufts, on where several setae insert (Fig. 7A, E). In the last instar larvae, there are three main types of setae: needle-shaped, spiral-shaped, and penniform (Fig. 7B–D). Compared to spiral-shaped setae, penniform setae are longer and have dense microtrichia. When touched, the hollow setae can easily break and irritate the skin (Fig. 7F). In addition to helping the larvae crawl and spread, the setae can be used to identify the taxonomic status of the larvae based on the number and arrangement of their hair tufts.

Funnel warts

On abdominal segments VI to VII, the larval funnel warts exhibit two distinct colors: red (♂: n = 29a, ♀: n = 27a) and creamy yellow (♂: n = 20a, ♀: n = 21a) (Fig. 8A–D). The findings showed no correlation between the gender of G. menyuanensis and the intraspecific color differences of the funnel warts (χ2= 0.003, P = 0.956). The funnel warts have an oval, volcano-shaped aperture. At the proximal opening of the funnel, furrows and a few secretions are visible (Fig. 8C, D). When viewed from within the larva, prominent muscle insertion points can be seen at the bottom of the funnel, and many trichomes are visible only inside. The larvae’s body will curl into a ball, and their versible osmeterium will expand outward to form a papillary bulge in response to external stimulation. According to the ultrastructure, many well-developed secretory cells are connected to the hollow column-shaped organ dispersed across the gland’s surface (Fig. 8E, F).

Funnel warts of the last instar larva of G. menyuanensis. (A) Yellow funnel warts; (B) red funnel warts; (C) yellow funnel warts light micrograph; (D) red funnel warts light micrograph; (E) funnel warts scanning electron microscope; (F) funnel warts magnification. fw: funnel warts; fwa: funnel wall.

Chaetotaxy of the first-instar larvae

For the left side of the body, the chaetotaxy of the first larval trunk is shown (Fig. 9, S9). Chaetotaxy on thorax (T1–T3) and the abdominal segments 1–10 (A1–A10) show similar setal arrangement.

The distribution diagram of the cluster of the first instar larva of G. menyuanensis. (A) Light micrograph of first instar larva; (B) scanning electron microscope of the first instar larva; (C) dorsal cluster; (D) subdorsal cluster; (E) lateral cluster; (F) subventral cluster; (G) first-instar larva chaetotaxy. D: dorsal cluster; PD: predorsal cluster; SD: subdorsal cluster; L: lateral cluster; SV: subventral cluster; V: ventral cluster; CV: central ventral cluster; Sp: spiracle; T1: prothorax; T2, T3: meso- and meta-thorax; A1–A10: abdominal segment.

Prothorax (T1)

The prothorax bears an enormous prothoracic shield, on which are three setigerous tubercles: dorsal cluster (D), subdorsal cluster (SD), and lateral cluster (L). With 22 setae, the dorsal cluster (D) is anterior to the subdorsal cluster (SD). There are 20 setae on the lateral cluster (L) and 24 on the subventral cluster (Table 2; Fig. 9, S9). Each seta is a single, equal-length stiff filament that rises directly from the cluster.

Meso- and meta- thorax (T2, T3)

In chaetotaxy, the meso- and meta-thorax are identical. The single bristle inserts on the dorsal cluster (D), subdorsal cluster (SD), lateral cluster (L), and subventral cluster (SV). With 22 setae, the setae rising from the dorsal cluster (D) are significantly more noticeable than the rest. The subdorsal cluster (SD) and lateral cluster (L) have 12 and 14 bristles, respectively. The subventral cluster (SV) has the smallest number of setae, with 9 bristles (Table 2; Fig. 9, S9).

Abdominal segments 1 and 2 (A1, A2)

Regarding chaetotaxy, the first two abdominal segments are the same in that they lack any appendages. Very noticeable setae rise from the dorsal cluster (D) and subdorsal cluster (SD). With 3 setae, the predorsal cluster (PD) is located anterolateral to the abdominal prolegs. With 11 setae, the lateral cluster (L) is anterior to the prothoracic spiracle. There are 3 shorter setae in the ventral cluster (V) and 8 in the subventral cluster (SV). On these segments, the central ventral seta (CV) is the shortest (Table 2; Fig. 9, S9).

Abdominal segments 3 and 6 (A3–A6)

Except for the absence of the V and CV clusters, the morphology of the A3 and A4 segments is identical, with five different types of clusters (PD, D, SD, L, and SV) that follow the same pattern as the A1 and A2 segments. A5 and A6 segments had the identical morphology as A3 and A4, with four types of clusters (D, SD, L, and SV), except for the absence of predorsal cluster (PD) (Table 2; Fig. 9, S9).

Abdominal segment 7 (A7)

Segment A7, with six types of clusters (D, SD, L, SV, V, and CV), is similar to that in segments A1 and A2, other than the absence of a predorsal cluster (PD) (Table 2; Fig. 9, S9).

Abdominal segment 8 (A8)

The setal arrangement and number of bristles originating from the predorsal cluster (PD), dorsal cluster (D), subdorsal cluster (SD), lateral cluster (L), ventral cluster (V), and central ventral cluster (CV) on A8 are the same as those on A1 and A2, except for the lack of a subventral cluster (SV) (Table 2; Fig. 9G, S9).

Abdominal segment 9 (A9)

The setae on A9 are comparably shorter, and the number of setae ascending from dorsal cluster (D), subdorsal cluster (SD), ventral cluster (V), and central ventral cluster (CV) are identical to that on A8 except for the lateral cluster (L: 8) (Table 2). The predorsal cluster (PD) and the spiracle are lacking compared to the setae layout on A8 (Fig. 9G, S9).

Abdominal segment 10 (A10)

The dorsal cluster (D) and the lateral cluster (L) are located on the dorsal sclerite of A10. Although the dorsal cluster (D) has a large surface area, it only has seven bristles. The lateral seta (L) is located ventral to the anal proleg with three setae (Fig. 9G, S9F).

Discussion

Our field investigation found that the larvae of G. menyuanensis are similar to other sympatric Gynaephoraspecies in some morphological features, all of have black setae trunk, positive redhead capsule, and a pair of red or creamy yellow funnel warts on the abdominal segment11 (Fig. S1). Traditional morphological identification used to identify sympatric Gynaephora species may result in incorrect results. Morphological identification is only valid for specific life stages or sexs, and many individuals cannot be identified according to existing search Table14. Genetic-based systems, and DNA barcoding (mitochondrial DNA cytochrome c oxidase I gene, COI) are now an accurate approach for the identification of species and have provided accurate species-level identification for many sympatric species15. In this study, we conducted DNA barcoding technology combined with traditional morphological identification to provide a basis for accurate and efficient taxonomic classification. In addition, SEM was used for the first time to systematically describe the external morphological characteristics, Chaetotaxy of the firstinstar larvae and sensillary ultrastructure of antennae and mouthparts of the mature larva of G. menyuanensis.Mandibles play key roles in food handling of insect larvae. The morphological structures of mandibles, especially cutting incisors, are diverse to adapt to different food resources and feeding habits16. In Lepidoptera, the larval mandibles are furnished with 15 teeth in leaf feeding Sericinus montela Grey17, eight teeth in pine-feeding Dendrolimus kikuchii Matsumura18, six dentitions in the diamond back moth Plutella xylostella (Linnaeus) and leaf-mining Calycopis bellera Hewitson19, five teeth in the polyphagous Helicoverpa armigera Hardwick20. In the mature larvae of Notodontidae, the incisors are fused into a smooth cutting edge21. In this study, the mature larval mandibles of G. menyuanensis have four incisor teeth on the mesal cutting margin, suitable for cutting grasses, similar to those of Actias. sinensis and A. selene16. The mandible of the first larvae is heavily sclerotized, forming three incisors on the apical margin (Fig. S4A). We speculate this phenomenon might be related with that G. menyuanensis overwinters underground as the first larvae which is mainly fed on the herbage roots. The morphological diversity among the mandibles of chewing insects might be related to the feeding habits of host plants22.

Insect sensilla are essential for sensing sex pheromones and plant volatiles in the environment, courtship, mating, and oviposition23,24,25. Through SEM observation, we were able to identify four types of sensilla (Figs. 3 and 4, S5; i.e., Sensilla basiconica, Sensilla chaetica, Sensilla trichodea, and Sensilla styloconica) on the antennae and mouthparts of the mature larvae of G. menyuanensis. These types of sensilla are morphologically similar to other Lepidoptera larvae that have been previously reported (e.g., Noctuidae26, Papilionidae27, Carposinidae28, and Sesiidae29). We identified two varieties of Sensilla trichodea in the antennae and maxillae. Their smooth walls and tips, and their positions suggest that these sensilla may be chemosensory receptors to taste food. Additionally, we discovered that Sensilla basiconica (Sb I) are oblique striation-welled with many minute irregular wrinkle-shaped pores at their blunt tips. These pores serve an olfactory purpose that aids larvae in searching for and locating host plants30. According to research on the antennal sensilla of Holcocerus hippophaecolus, the primary functions of Sensilla chaetica are to sense physical and mechanical stimuli, choose which mechanical stimulation of the external environment to apply, and coordinate the movement of the mouthparts31. Various morphological traits of Sensilla chaetia, Sensilla styloconic, and Sensilla basiconic have been observed on the antennae in this study (Fig. 4). Together with olfactory receptors, these sensilla may be involved in the movement of the maxillae and labium, and the detection of food or tunnel structure.

The prolegs are morphologically different among families, adapted to be highly robust and powerful in Saturniidae and Sphingidae32and deteriorated in Geometridae and some Noctuidae30. Three pairs of thoracic legs, each with a sharp pretarsus terminally, are present in the final instar larvae of G. menyuanensis (Fig. 5, S6). The strong thoracic legs of herbivorous insects can support the entire body during feeding, and they also function as the center of movement when the larvae rest on the plant’s surface33. Moreover, the unsegmented prolegs of the last instar larvae feature 17 to 25 crochets, whereas the first instar larvae only possess four crochets (Fig. 6, S8E, G). We assume that the morphological features of the thoracic and abdominal legs could have something to do with the local environment and host plants (Figs. 1 and 5, S7). One primary characteristic that sets Lepidopteran larvae apart from other polypod larvae is their crochets34. Our findings indicate that the number of crochets on G. menyuanensis larvae increases progressively from the first to the last instar, which can be used to identify the larval instars.

In Lepidoptera, larval taxonomy frequently relied on the first instar larvae, as their primary setae are constant in number, length and arrangement35. The final-instar larval setae usually specialized into stinging spines36or assembled as dense tufts as mimicry of some Arctiidae, Lasiocampidae, and Lymantriinae37. The larvae of G. menyuanensisare covered by large hair tufts, which carry many setae. The hypothesis is that the venomous, itchy setae act as insulation against the cold weather38. In QTP, the black setae may also shield G. menyuanensisfrom harmful UV radiation1. In particular, in QTP, where habitats cannot provide shelter, grass caterpillars’ setae, which are sensitive to touch, substrate, and air-borne vibrations, transmit mechanosensory information that includes intraspecific communication between individuals or early warning of the approach of enemies such as parasitoid wasps that wish to lay their eggs on or into their bodies39.

In the process of field surveys and laboratory rearing of the larvae, we found that when the larvae were stimulated externally, their bodies curled into a ball, and extruded the funnel warts, exposing the secretion within the funnel to the exterior just like osmeterium of Papilionidae larvae. The authors realized the funnel warts are essentially orifices of exocrine glands that secrete the substance, as noted by Deml and Dettner in their study of Noctuoidea larvae40,41,42. The red or creamy yellow funnel warts presenting on the last instar larvae of G. menyuanensis (Fig. 8) have a particularly high potential for the classification of the inter-relationships within the Lymantriinae. Through use of SEM, Deml and Dettner examined the morphology of the funnel warts in four lymantriid species: Lymantria dispar (L.), L. monacha (L.), L. concolor Walker, and larvae of Euproctis chrysorrhoea(L.)41,42. Chemical analyses of the secretions of the above-mentioned Lymantriaspp. revealed that they contain several aromatic compounds (e.g., benzaldehyde and phenylacetaldehyde), N-containing compounds (e.g., pyrazines, 2-pyrrolidinone and nicotine), organic acids, and other chemicals such as glycerol and isopropyl myristate43,44. The secretions may work as a chemical defense against enemies, enhancing the protective properties of the hair tufts that cover many Lymantriid larvae45. Meanwhile, we discovered that gender had no bearing on the variation in color of G. menyuanensis funnel warts. Thus, more investigations are needed to determine the underlying molecular mechanism of the color change of the funnel warts. The results of the present study may inform future studies on the comparative morphology of these eight congeneric larvae with sympatric distribution. Morphological descriptions and fine structure studies on larvae could provide valuable reference for quick identification and control of these notorious grassland caterpillars.

Materials and methods

Insect collection and rearing

In order to get insight into the natural distribution areas of G. menyuanensis, general surveys with targeted site assessments were carried out with expertise from local collaborators in Qinghai and Gansu provinces during the grassland growth season (May–August) from 2021 to 2023. A total of 20 field survey plots were set up based on the geographic locations of species occurrences. Each field survey plot covered an area of 0.5 hm2, in which five quadrats were selected randomly with an area of 1 m2 for ground observations (Fig. 1C). The G. menyuanensis has high density (usually 2–50 head/ m2, the highest recorded density reaching 200 individuals per m2). The larvae in their first and last instars were reared in the laboratory at Qinghai University after being placed in plastic containers (diameter 4 cm, height 12 cm), according to the sampling areas. All samples were kept in an incubator at 18.0 °C ± 2.8 °C and a relative humidity of 60% ± 10%. Seedlings of Stipa capillata L. and Artemisia lancea Van. were purchased from Suqian Verdara Green Engineering Co., Ltd., China, and cultivated in the green house of Qinghai University until the forage grasses grow to 20 cm. The fresh grasses were fed to the grassland caterpillar larvae, and daily records of the molting time and pupation time were made.

Identification

The larvae samples were identified based on external morphology by the Provincial Key Laboratory of Agricultural Integrated Pest Management (Yunxiang Liu for Research in Entomology, Xining, Qinghai)46. For the identification of molecular technologies, 13 last instar larvae from each sampling location were selected, and the DNA was extracted using the Biospin insect genomic DNA extraction kit (Bioer Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI: LCO1490-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG, HCO2198-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA) was amplified47. A total of 25 µL was used in the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system. The procedures were initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, then 95 °C, 30 s, 30 cycles, followed by annealing at 52°C for 1 min, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and finally extension at 72 °C for 10 min. To confirm that the PCR results were the intended target fragments, the products were identified using 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis. For sequencing, Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology received the qualified DNA products. Sequence chromatograms were aligned in Clustal X v2.0.21 after being examined with Chromas Pro v2.23 (Technelysium Pty Ltd., Australia)48. BioEdit v7.0.9.0 was used to manually remove the gappy columns at the beginning and end of the alignment49. Using MEGA v6 to compute the genetic distance between interspecies, the nucleotide similarity with reference sequences—obtained by retrieving DNA barcode data from the Barcode of Life database (BOLD Systems v4, www.boldsystems.org)--was determined50. We also reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships of all populations with COIgenes. The trees were performed using maximum likelihood (ML) implemented in PhyML v 3.051and Bayesian inference (BI) using MrBayes MRBAYES v 3.1.252. Sequences from two closely related species, G. jiuzhiensis and G. minora, obtained from Yuan et al.1, were used as outgroup taxa for the phylogenetic analysis. The grassland caterpillar COI sequences obtained in this study were deposited into the GenBank database under the accession numbers PP238621–PP238625. The reference sequences were downloaded from the GenBank database (accession numbers KF887535–KF887540, KF887600, KF887640).

Morphological observation

Gyneaphora menyuanensis larvae in their first and last instars were washed with 0.1 mol/L (pH = 7.4) phosphate buffer and dried at room temperature. A Nikon SMZ1500 stereomicroscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to examine the external morphology of the specimens and a Scientific Digital micrography system equipped with an Auto-montage imaging system and a QIMAGING Retiga 4000R digital camera (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) was used to take photographs.

The larvae in their first and last instars were fixed in hot Dietrich’s solution (formalin: 95% ethanol: glacial acetic acid: distilled water = 6:15:1:80, v/v) for the scanning electron microscope. They were then allowed to stand for 24 h at room temperature under a fume hood before being preserved in 75% ethanol53. After being dehydrated for 20 min in a series of ethanol baths (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100%), larvae were freeze-dried for 4 h, sputter coated with gold, and studied under a scanning electron microscope (JEOL 7900 F) at 5 kV54. Larval morphological terminology follows Stehr55.

Conclusions

In summary, this study employs general surveys and targeted investigations to systematically elucidate the natural distribution areas of G. menyuanensis. The results indicate that this species is primarily found in the alpine meadows of the northeastern region of Qinghai and parts of Gansu Province. For the first time, the ultramorphology of the immature stages of G. menyuanensis is observed using scanning electron microscopy, with particular attention given to the chaetotaxy of the first instar larva, as well as the mouthparts and their sensilla of the final instar larva. The eruciform larvae are densely covered with three main types of setae and bear two-color funnel warts. Our findings support efforts to predict the occurrence of G. menyuanensis and facilitate the rapid identification of this endemic species. Given their significant ecological role, considerable attention should be devoted to the larvae of G. menyuanensis for the protection of alpine meadows.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript and the supplementary file. Nucleotide sequences supporting the conclusions of this study can be found by the accession numbers (PP238621–PP238625), at NCBI GenBank: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/.

References

Yuan, M. L. et al. Mitochondrial phylogeny, divergence history and high-altitude adaptation of grassland caterpillars (Lepidoptera: lymantriinae: Gynaephora) inhabiting the Tibetan plateau. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 122, 116–124 (2018).

Zhang, Q. L. & Yuan, M. L. Research status and prospect of grassland caterpillars (Lepidoptera:Lymantriidae). Pratacult Sci. 30, 638–646 (2013) (in Chinese).

Lai, Y. P. et al. Genome assembly of the grassland caterpillar Gynaephora qinghaiensis. Sci. Data. 12, 158 (2025).

Yuan, M. L. et al. Mitochondrial phylogeography of grassland caterpillars (Lepidoptera: lymantriinae: Gynaephora) endemic to the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Ecol. Evol. 14, e70270 (2024).

Yan, L., Chou, Y., Mei, J. & Huo, K. Three new species of Gynaephora (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) from Qinghai. Acta Biol. Plateau Sin 13, 121–126 (1997) (in Chinese).

Zhang, Q. L. et al. Gene sequence variations and expression patterns of mitochondrial genes are associated with the adaptive evolution of two Gynaephora species (Lepidoptera: Lymantriinae) living in different high-elevation environments. Gene 610, 148–155 (2017).

Yuan, M. L., Zhang, L. Q., Wang, Z. F., Guo, Z. L. & Bao, G. S. Molecular phylogeny of grassland caterpillars (Lepidoptera: lymantrinae, Gvnaephora) endemic to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateay. Plos One. 10, 6 (2015).

Grimaldi, D. & Engel, M. S. Evolution of the Insects (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Vegliante, F. & Hasenfuss, I. Morphology and diversity of exocrine glands in lepidopteran larvae. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 57, 187–204 (2012).

Mahlerová, K., Jakubec, P., Novák, M. & Růžička, J. Description of larval morphology and phylogenetic relationships of Heterotemna tenuicornis (Silphidae). Sci. Rep-UK. 11, 16973 (2021).

Yan, L. Studies of taxonomy, geographic distribution in Gynaephora genus and life-history strategies on Gynaephora menyuansis. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou Universtiy, Lanzhou, China, (in Chinese) (2006).

Antil, S. et al. DNA barcoding, an efective tool for species identifcation: a review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 761–775 (2023).

Hebert, P. D. N., Cywinska, A., Ball, S. L. & deWaard J. R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. P Roy Soc. B-Biol Sci. 270, 313–321 (2003).

Ho, J. & Sparagano, O. A. E. Parasitic mite fauna in Asian poultry farming systems. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 1–8 (2020).

Ma, Y. L. et al. Rapid and accurate identification of Tenuipalpus hornotinus based on morphology and DNA barcode technology. Environ. Entomol. 1–15 (2024) (in Chinese).

Zhang, Y. J., Fang, H. & Jiang, L. Comparative morphology of the larval mouthparts among three Actias (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae), with descriptions on atypical spinnerets. Zoomorphology 141, 173–181 (2022).

Wang, Z. H. & Jiang, H. Ultramorphology of the mature larvae of Sericinus Montela grey (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae), with descriptions of osmeterium using a novel method of larval preservation. J. Nat. Hist. 57, 1–4 (2023).

Men, Q. & Wu, G. Ultrastructure of the Sensilla on Larval Antennae and Mouthparts of the Simao Pine Moth, Dendrolimus kikuchii Matsumura (Lepidoptera: Lasiocampidae). Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 118, 373–381 (2016).

Li, Y. P., Du, X., Liu, F. F., Li, Y. & Liu, T. X. Ultrastructure of the sensilla on antennae and mouthparts of larval and adult Plutella Xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). J. Integr. Agric. 17, 1409–1420 (2018).

Santos, L. Q., Casagrande, M. M. & Specht, A. Morphological characterization of Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: noctuidae: Heliothinae). Neotrop. Entomol. 47, 517–542 (2018).

Liu, J. X. & Jiang, L. Comparative morphology of the larval mouthparts among six species of Notodontidae (Insecta, Lepidoptera), with discussions on their feeding habits and pupation sites. Deut Entomol. Z. 70, 357–368 (2023).

Jiang, L. & Hua, B. Z. Functional morphology of the larval mouthparts of Panorpodidae compared with Bittacidae and Panorpidae (Insecta: Mecoptera). Org. Divers. Evol. 15, 671–679 (2015).

Leal, W. S. Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 373–391 (2013).

Field, L., Pickett, J. & Wadhams, L. Molecular studies in insect olfaction. Insect Mol. Biol. 9, 545–551 (2000).

Fatouros, N. E., Dicke, M., Mumm, R., Meiners, T. & Hilker, M. Foraging behavior of egg parasitoids exploiting chemical information. Behav. Ecol. 19, 677–689 (2008).

Todd, M. G. et al. Identification of heliothine (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larvae intercepted at U.S. Ports of entry from the new world. Econ. Entomol. 112, 603–615 (2019).

Wang, Z. H. & Jiang, L. Ultramorphology of the mature larvae of Sericinus Montela grey (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae), with descriptions of osmeterium using a novel method of larval preservation. Nat. Hist. 57, 38–53 (2023).

Zhao, L., Bao, Z. H. & Lu, L. Ultrastructure of the sensilla on larval antennae and mouthparts in the Peach fruit moth, Carposina Sasakii Matsumura (Lepidoptera: Carposinidae). Micron 42, 478–483 (2011).

Gilson, R. P. M., Oleg, G. G., Júlia, F. & Gislene, L. G. A peculiar new species of gall-inducing, clearwing moth (Lepidoptera, Sesiidae) associated with Cayaponia in the Atlantic Forest. Zookeys 24, 39–63 (2019).

Barsagade, D. D., Khurad, A. M. & Chamat, M. V. Microscopic structure of mouth parts sensillae in the fifth instar larvae of erisilkworm, Philosamia Ricini (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). Entomol. Zool. 1, 15–21 (2013).

Liu, L., Zhang, Y., Yan, S. C., Yang, B. & Wang, G. R. Ultrastructural and descriptive study on the adult body surface of Heortia vitessoides (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Insects 14, 687 (2023).

Rougerie, R. & Estradel, Y. Morphology of the preimaginal stages of the African emperor moth Bunaeopsis licharbas (Maassen and Weyding): phylogenetically informative characters within Saturniinae (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae). Morphology 269, 207–232 (2008).

Matsuoka, Y. J., Murugesan, S. N., Prakash, A. & Monteiro, A. Lepidopteran prolegs are novel traits, not leg homologs. Sci. Adv. 9, 41 (2023).

Common, I. F. B. Moths of Australia (Melbourne University, 1990).

Jiang, L. & Hua, B. Z. Morphology and chaetotaxy of the immature stages of the Scorpionfy Panorpa liui Hua (Mecoptera: Panorpidae) with notes on its biology. J. Nat. Hist. 47, 2691–2705 (2013).

Lin, Y. C., Lin, R. J., Braby, M. F. & Hsu, Y. F. Evolution and losses of spines in slug caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Limacodidae). Ecol. Evol. 9, 9827–9840 (2019).

Wagner, D. L. Caterpillars of Eastern North America: a Guide To Identifcation and Natural History (Princeton University Press, 2005).

Uhlikova, H., Nakladal, O., Jakubcová, P. & Turčáni, M. Outbreaks of the Nun moth (Lymantria monacha) and historical risk regions in the Czech Republic. Šumar List. 135, 477–486 (2011).

Yang, Q. Z. et al. A new species of Pteromalus (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) parasitizing pupa of Gynaephora qinghaiensis (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) from Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Sci. Silva Sinica 56, 99–105 (2020) (in Chinese).

Reinhold, D. & Konrad, D. Comparative morphology and evolution of the funnel warts of larval Lymantriidae (Lepidoptera). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 30, 15–26 (2001).

Deml, R. & Dettner, K. Extrusible glands and volatile components of the larval Gypsy moth and other tussock moths (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). Entomol. Gen. 19, 239–252 (1995).

Deml, R. Morphological details of the larval funnel warts of Lymantria dispar (Linnaeus, 1758) (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). Entomol. Z. 110, 168–170 (2000).

Aldrich, R. et al. Biochemistry of the exocrine secretion fromgypsy moth caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 90, 75–82 (1997).

Deml, R. & Dettner, K. Chemical defence of emperor moths Andtussock moths (Lepidoptera: saturniidae, Lymantriidae). Entomol. Gen. 21, 225–251 (1997).

Deml, R. & Dettner, K. Balloon hairs of gipsy moth larvae (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae): morphology and comparative chemistry. Comp. Biochem. Phys. B. 112, 673–681 (1995).

Yan, L., Jiang, X. & Wang, G. Characterization of larvae development in Gynaephora menyuanensis (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). Acta Pratacult Sci. 14, 116–120 (2005) (in Chinese).

Folmer, O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R. & Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome coxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotech. 3, 294–299 (1994).

Jeanmougin, F., Thompson, J. D., Gouy, M., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. Multiple sequence alignment with clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 403–405 (1998).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 95–98 (1999).

Tamura, K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 (2011).

Guindon, S. & Gascuel, O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 (2003).

Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes3: bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (2003).

Jiang, L. & Hua, B. Z. Morphological comparison of the larvae of Panorpa obtusa Cheng and Neopanorpa lui chou & Ran (Mecoptera: Panorpidae). Zool. Anz. 255, 62–70 (2015).

Qu, Z. F., Jia, Z. C. & Jiang, L. Description of the third instar larva of the stag beetle Prismognathus dauricus Motschulsky, 1860 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeoidea: Lucanidae) using electron microscopy. Micron 120, 10–16 (2019).

Stehr, F. W. Immature Insects (Kendall/Hunt Publishing, 1987).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Dr. Luchao Bai (Qinghai University, Xining, China) for kindly providing the optical microscope.

Funding

The Natural Science Foundation of Qinghai Province (Grant No. 2022-ZJ-981Q) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32160263) funded this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y., H.N.S. and Y.X.L. conceptualized and designed the study. C.Y., J.P.F., S.Y.L. and Y.X.L. prepared all the figures and analyzed the data. C.Y., H.N.S. and Y.X.L. discussed the results and wrote the original draft. C.Y., H.N.S. and Y.X.L. critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The plant and insect collection and use were in accordance with all the relevant guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, C., Liu, Y., Shao, H. et al. Identification, distribution and ultramorphology of the larvae of Gynaephora menyuanensis (Lepidoptera: Lymantriinae) endemic to Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Sci Rep 15, 8889 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93345-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93345-2