Abstract

This study explores the potential of rubberized concrete-filled steel tube (RCFST) columns as a sustainable solution for mitigating waste tire rubber pollution. The research focuses on utilizing waste rubber particles to partially replace sand in the concrete, thereby modifying the concrete mix ratio. Axial compression tests were performed on 20 stub column specimens following exposure to elevated temperatures, comprising 10 circular and 10 square steel tubes. The key experimental parameters investigated were the rubber replacement ratio, temperature, and elevated temperature duration. The impact of these parameters on the load-bearing behavior of RCFST columns after exposure to elevated temperatures was assessed through analysis of failure modes, load–displacement response, and stress–strain relationships. Irregular buckling behavior during loading was observed in RCFST columns exposed to elevated temperatures, according to experimental results. The failure mode is characterized by an oblique circular shear failure that is non-parallel. The ultimate bearing capacity decreased with increasing rubber replacement ratio, temperature, and elevated temperature duration. The detrimental effect on the performance of RCFST columns was amplified at higher temperatures and longer durations of elevated temperature exposure. Specimens with a 20% rubber aggregate replacement ratio exhibited a significant reduction in stiffness, with ultimate load decreasing by 28% and 25% for circular and square columns, respectively, while ductility improved. A substantial degradation in ultimate bearing capacity was observed when the temperature changed from 20 °C to 800 °C, with reductions of 35% and 43% for circular and square columns, respectively. Based on experimental findings, and following the principles outlined in GB 50,936–2014 and EC4, a simplified formula was derived to calculate the ultimate bearing capacity of RCFST columns after exposure to elevated temperatures. The proposed formula demonstrated good correlation with the experimental data when compared.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the rubber tyre industry has become a pivotal supporting sector for the automotive industry, achieving significant market presence. Global tyre production has surpassed 2 billion units annually, while tyre waste generation has reached approximately 42 million tons. Concurrently, tyre usage has been on the rise, resulting in a rapid escalation in tyre waste generation. The global recycling rate for waste tires is 74%, while China, as the largest producer of tires worldwide, has a recycling rate of approximately 50%. This has resulted in waste tires made from rubber becoming one of the most prevalent sources of waste on Earth. Because of their massive quantity and non-biodegradable nature, waste rubber poses significant environmental pollution and fire hazards, making it a major contributor to modern environmental issues1,2,3. The primary methods for disposing of waste rubber tires are incineration and landfilling. However, incineration produces harmful gases that pollute the atmosphere, while landfilling leads to soil and groundwater contamination due to the rubber’s resistance to degradation4,5. The improper disposal of waste rubber represents a significant loss of valuable resources and poses substantial environmental and public health risks, underscoring the growing imperative for effective recycling strategies. Consequently, many researchers have sought new processing methods to convert waste tires into usable rubber particles for application in construction materials6. By utilizing rubber particles as aggregates to partially replace natural aggregates in normal concrete (NC), rubberized concrete (RuC) has been proposed7.

RuC, as an emerging green construction material, is garnering widespread attention due to its unique performance advantages. Topçu et al.8 conducted a significant study on the trade-off in mechanical behavior arising from the partial substitution of natural aggregates with waste tire rubber particles in concrete. They found that increasing rubber content reduced strength but simultaneously enhanced ductility considerably compared to NC. Other researchers9,10,11 have investigated the effects of varying rubber particle content on the mechanical properties of concrete, reaching conclusions largely consistent with Topçu et al.8. Other studies12,13,14,15 found that incorporating rubber particles into concrete improves properties such as ductility, seismic performance, deformation capacity, and ultimate strain, but at the same time, it causes a significant reduction in compressive strength and elastic modulus, thereby restricting the structural applicability of RuC. To address these issues, combining RuC with steel tubes to form RCFST composite members has been proposed as a viable solution3,16,17.

Concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns, as a novel concrete structure, were widely used in building and bridge engineering, attracting considerable attention due to their high strength, stiffness, and strong seismic resistance18,19. CFST columns utilize the composite action between an internal concrete core and an external steel tube to achieve superior structural performance. The concrete core inhibits local buckling in the steel tube, while the steel tube effectively confines the concrete, enhancing its compressive strength and ductility. Although CFST columns have been widely utilized in engineering applications, they still face several critical challenges in practical implementation. Traditional CFST columns are prone to concrete spalling and steel tube softening under high temperatures, leading to a significant reduction in load-bearing capacity. Additionally, the substantial difference in thermal expansion coefficients between the steel tube and concrete can result in interfacial debonding, compromising the overall composite action. CFST columns are susceptible to brittle failure under extreme loading conditions, exhibiting insufficient ductility to meet seismic requirements in high-intensity earthquake zones. The inherent brittleness of concrete also limits the energy dissipation capacity of the overall structure. Meanwhile, CFST columns rely heavily on natural aggregates and steel, resulting in substantial resource consumption and posing environmental and sustainability challenges. Particularly, CFST columns’ mechanical qualities significantly deteriorate when exposed to high temperatures, which critically undermines their structural performance and raises substantial concerns regarding their safety under service conditions.

Wang et al.20 examined the effect of concrete strength grade on the fire resistance of CFST columns under load, and found that fire resistance time is significantly affected by the concrete core’s strength and diameter. Thumrongvut et al.21 examined the post-fire behavior of square CFST columns, finding that high temperatures significantly impact both the axial load-bearing capacity and ductility of specimens. The behavior of recycled aggregate CFST columns at various high temperatures was studied by Li et al.22. Under the same temperature conditions, specimens containing recycled aggregates exhibited lower compressive strength and elastic modulus relative to those with ordinary concrete, a phenomenon that became more pronounced with increasing recycled aggregate content and temperature. High temperatures cause a substantial decrease in the mechanical properties of concrete and steel tubes, such as strength and stiffness, which in turn reduces the Overall performance of CFST columns22. Given that rubber particles exhibit excellent thermal stability and ductility at elevated temperatures, can reduce concrete spalling and improve steel–concrete interfacial bonding when incorporated into concrete and combined with steel tubes. This approach enables CFST columns to demonstrate improved plastic deformation capacity under extreme loading conditions, thereby enhancing ductility and seismic performance. Moreover, the utilization of recycled waste tires in CFST columns not only reduces the consumption of natural aggregates but also provides a novel pathway for the high-value-added utilization of solid waste, aligning with the principles of green building development. To enable the effective application of RCFST columns in building structures and to improve their fire resistance, a detailed investigation of their axial compression performance after exposure to elevated temperatures is necessary.

This paper explores the axial compressive behavior of RCFST columns after exposure to elevated temperatures by utilizing specimens with rubber aggregate replacement ratio (R), temperature (T), and elevated temperature duration (t) as variables. The experimental results were analyzed to investigate the effects of high temperatures on the load-carrying capacity, load–displacement relationship, stress–strain relationship, deformation characteristics, and failure modes of RCFST columns. Based on these findings, a predictive formula was developed to calculate the ultimate bearing capacity of RCFRT columns after exposure to elevated temperatures.

Experimental program

Test specimens

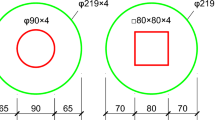

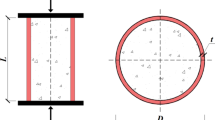

The experimental program encompassed the design and testing of 20 specimens, comprising 18 RCFST columns and 2 CFST columns. And they are equally divided into two cross-sectional geometries, circular and square. The height and cross-sectional dimensions of all specimens are shown in Fig. 1. The test included the following parameters: R at 0%, 5%, 10% and 20%; T at 20℃, 200℃, 400℃, 600℃ and 800℃; and t at 0 min, 30 min, 90 min, and 180 min. The key steps of the experimental process are shown in Fig. 2.

Materials

Concrete

In this experiment, the mix proportion was designed in accordance with the standard natural concrete C3023. Fine aggregate consisted of ordinary natural river sand, classified as medium sand. The coarse aggregate exhibited a particle size range of 5–20 mm. The mixing water was derived from municipal tap water. Table 1 shows the concrete mix proportions.

Rubber particles

Rubber with a size of 20 mesh was utilized. For each distinct rubber replacement ratio, three standard concrete cube specimens were prepared. These specimens were subjected to high-temperature treatment following a 28-day curing period. Subsequently, the mechanical properties of the concrete under various parameters were measured according to GB/T50081-201924. The results are shown in Table 2.

Steel tubes

The steel tubes were fabricated according to the experimental design specifications, ensuring that both ends of the cross-section remained horizontally intact. The yield strength of the steel was defined as the ratio of the force causing 0.2% plastic strain to the cross-sectional area. Table 3 shows the mechanical properties of the steel.

Experimental setup and measuring

High-temperature equipment

The experiment utilized an SX2-12–10 box-type resistance furnace (Fig. 3) with a maximum temperature capability of 1000℃. The internal working dimensions of the furnace are 500mm × 300mm × 200mm. The specimen was heated in a furnace to the target temperature and held there for the designated duration.

Loading equipment

A YAW-3000 microcomputer-controlled electrohydraulic servo pressure testing machine was used to conduct axial compression tests on the specimens in the Structural Engineering Laboratory at East China University of Technology. Displacement and deformation data were measured with a 50-range displacement transducer. Figure 4 shows the schematic diagrams of the equipment and instrumentation.

Loading method

Before undergoing axial compression testing, the mid-height region of each specimen was ground to ensure optimal contact for strain gauge adhesion. Two pairs of orthogonally oriented strain gauges were then attached to the prepared surface. The specimen was centrally positioned on the lower loading platen, and the upper platen was lowered with a 1–2 mm gap to the specimen top. Two LVDTs were employed to assess axial displacement, while four strain gauges were mounted at the mid-height of the columns, spaced 90° apart. After stabilizing the load measurements, the test was conducted under displacement-controlled loading at a rate of 0.5mm/min. The experiment was terminated when the load dropped to approximately 80%25 of the ultimate bearing or when the specimen was compressed by around 35mm if the load drop was not evident. Figure 5 shows a sketch of the specimen loading.

Test results and analysis

Phenomena and failure modes

During the heating process, continuous emission of small quantities of water vapor from the exhaust vents was observed as the furnace temperature approached 200 °C. The water vapor emission became most pronounced at 400 °C, accompanied by a pungent odor. The intensity of this odor increased proportionally with the replacement ratio. After high-temperature exposure, the specimens maintained good integrity without any deformation or blistering phenomena. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the outer steel tube of the specimens exhibited distinct color variations with increasing temperature. As the temperature climbed beyond 400 °C, the steel tube surface lost its metallic luster and developed numerous evident oxidation layers, transforming to a reddish-brown color that progressively darkened with increasing temperature. In addition to the change in surface color, some of the specimens were accompanied by fine cracks on the surface. These phenomena are comparable to the study by Habib et al.26,27 After 24 h of natural cooling, mass measurements revealed changes in specimen weight. Table 4 and Fig. 7 show that the mass loss ratio demonstrated a positive correlation with rubber replacement ratio, temperature, and elevated temperature duration.

The failure mechanism of RCFST columns after exposure to elevated temperatures under axial compression comprises three distinct stages: core concrete cracking, steel tube yielding, and overall column instability. The load-bearing process involves shared stress distribution between the core concrete and steel tube. The lateral confinement provided by the steel tube promotes the re-closure of cracks along the compression axis following concrete cracking, corroborating findings by Shen et al.28. During loading, the steel surface exhibited progressive irregular buckling. Specimens exposed to temperatures exceeding 400℃ exhibited extensive peeling of the steel tube’s oxidation layer. Shear failure was evidenced by the presence of 45° inclined slip lines on specimen surfaces27. As shown in Fig. 8, shear failure characterized by non-parallel oblique circular bulges is observed at the bottom, middle, and top of the column. Although the concrete surface at the top and bottom shows no obvious fissures, the steel tube shows considerable overall giving. As the load rises, the steel tube column expands slightly from compression, causing the bulges to thicken gradually. The specimen exhibits irregular local buckling of the steel wall. Figure 9 shows the failure mode of all specimens.

Load–displacement response

Influence of replacement ratio

Figure 10 shows the load–displacement curves of RCFST columns at various rubber aggregate replacement ratios. Initially, under axial loading, a linear elastic phase is observed, where the structural stiffness is primarily governed by the elastic moduli of the constituent materials. From Fig. 10(a), the control CFST columns demonstrate superior residual load-bearing capacity after high-temperature exposure. In Fig. 10(b), a progressive reduction in the initial slope and a flattening of the load–displacement curve are apparent as the rubber replacement ratio increases, signifying a decrease in overall stiffness. But the ductility was improved, which corroborates the study of Duarte et al29,30. A 10% rubber replacement ratio yields an optimal balance between deformation capacity and load-bearing strength, characterized by the absence of a pronounced post-peak softening behavior in the stress–strain response. This enhanced performance is attributed to the incorporation of rubber particles, which contribute to improved ductility of the confined concrete core3,31. In contrast, specimens with a 20% rubber replacement ratio exhibited a significant reduction in both stiffness and peak load. The peak loads of C-R20T600t180 and S-R20T600t180 specimens decreased by 28% and 25%, respectively. This degradation is primarily attributed to the combined effects of reduced concrete strength due to rubber inclusion and the exacerbation of this strength reduction under elevated temperatures32.

Influence of temperature

Figure 11 shows the load–displacement curves of RCFST columns at different temperatures. The initial stiffness of both circular and square RCFST columns declines with increasing temperature. This stiffness reduction results from the degradation of cement hydration products and the thermal decomposition of rubber particles at elevated temperatures, increasing concrete core porosity and reducing steel tube confinement efficiency. In Fig. 11(a), the peak load remains relatively high despite a slight decrease at 200 °C and 400 °C, suggesting the steel tube’s confinement of the concrete is not significantly compromised within this temperature range. In Fig. 11(b), at 400 °C, the specimen curve’s linear portion shortens, the peak load drops significantly, and ductility diminishes further. Therefore, 400 °C represents a critical threshold where high temperature markedly impacts square RCFST column performance. Beyond 600 °C, the decomposition of rubber particles and the reduction in steel tube strength cause notable decreases in the RCFST column’s bearing capacity and ductility. At 800 °C, the peak load reduces considerably, with a 35% decrease for C-R10T800t180 and a 43% decrease for S-R10T800t180. The circular steel tube provides uniform concrete confinement, enhancing its resistance to high temperatures. Conversely, the square cross-section is more susceptible to localized buckling at elevated temperatures due to stress concentrations, negatively impacting its overall performance30.

Influence of elevated temperature duration

Figure 12(a) and Fig. 12(b) show the load–displacement curves of RCFST columns following exposure to elevated temperatures for various isothermal holding periods. The general trend across all curves is consistent, yet extended exposure to elevated temperatures leads to a marked reduction in the stiffness, bearing capacity, and ductility of the RCFST columns. This deterioration intensifies progressively with increased exposure duration. When comparing square RCFST columns to their circular counterparts, the former exhibit a more pronounced decline in bearing capacity and stiffness. This phenomenon results from the more uniform confinement of circular steel tubes, which effectively delays concrete spalling and strength loss under elevated temperatures.

Stress–strain relationships

The stress–strain relationships of RCFST columns are shown in Fig. 13. In Fig. 13(a), following a 180 min exposure to a temperature of 600 °C, the mechanical characteristics of RCFST columns were markedly distinct from those of CFST columns. With an increase in the rubber replacement ratio from 0 to 20%, there was a gradual decline in peak stress, accompanied by a significant enhancement in ductility performance. The stress–strain curves became more gradual, indicating that rubber particle incorporation effectively suppressed concrete crack propagation under high temperatures and enhanced the energy dissipation and deformation capabilities of RCFST columns. At a 10% rubber replacement ratio, the stress–strain curve exhibited the most optimized performance, achieving a balanced relationship between peak stress and ductility. This suggests that an appropriate amount of rubber particles can mitigate microcrack expansion within concrete under high temperatures, thereby improving the overall mechanical properties of the specimens. In Fig. 13(b), at room temperature (20 °C), the RCFST columns demonstrated typical mechanical behavior of ductile composite materials, with stress–strain curves showing distinct ascending, plateau, and descending stages. These curves exhibited high peak stress and excellent energy absorption capacity, attributable to the confinement of steel tubes and the synergistic action of concrete. As the temperature exceeded 400 °C, the peak stress and elastic modulus of RCFST columns decreased significantly. The stress–strain curves became more gradual after the initial ascent, entering a pronounced yield stage, indicating microstructural damage to the concrete matrix and thermal decomposition of rubber particles, resulting in degradation of load-bearing capacity and ductility. In Fig. 13(c), the RCFST columns unexposed to high temperatures displayed the optimal mechanical performance, with the highest peak stress and exceptional ductility. As the high-temperature exposure duration increased, both peak stress and ductility gradually declined, with notable shifts in the characteristic points of stress–strain curves. After 180 min of high-temperature exposure, they reached their lowest peak stress and ductility levels, with stress–strain curves exhibiting pronounced plastic deformation characteristics. This demonstrates substantial deterioration of the concrete matrix and a marked decline in the steel–concrete bond performance resulting from extended exposure to elevated temperatures. Comprehensive analysis reveals that temperature elevation and extended high-temperature exposure both adversely affect specimen performance, reducing peak stress and ductility. However, an optimal rubber particle content (10%) can partially mitigate these negative effects by improving the specimens’ plastic deformation capacity and toughness.

Load-bearing capacity

The ultimate load capacities of RCFST columns are shown in Fig. 14. It is evident that the rubber replacement ratio, temperature, and elevated temperature duration significantly influence the ultimate load-bearing capacity. A decreasing trend in ultimate load-bearing capacity is observed with increasing rubber replacement ratio, temperature, and elevated temperature duration. Specifically, increasing the rubber replacement ratio from 0 to 20% resulted in a reduction of 28% and 25% in ultimate load-bearing capacity, respectively. Similarly, increasing the temperature from 20 °C to 800 °C resulted in a reduction of 35% and 43% in maximum load-bearing capacity. Following a 180 min exposure to a temperature of 600 °C, starting from room temperature, the ultimate bearing capacity of circular specimens decreased significantly from 644.41kN to 535.62kN, while that of square specimens exhibited a more pronounced reduction from 741.29kN to 492.10kN. These experimental results explicitly demonstrate that elevated temperature substantially deteriorates the mechanical performance of RCFST columns, and this degradation becomes increasingly pronounced with prolonged exposure duration.

Theoretical calculation of ultimate bearing capacity

Existing design codes

Significant research28,33,34 has been conducted in recent years to investigate the ultimate axial bearing capacity of CFST columns. This has resulted in the development of various calculation formulas, which have been incorporated into national and international design codes. Notable examples include the Chinese code GB 50,936–201435, Eurocode 4 (EC4)36, the American Concrete Institute code ACI 200537, and Japanese code AIJ 199738.

Chinese code GB50936-2014

where \(A_{sc}\) is the cross-sectional area of the composite CFST columns and \(f_{sc}\) is the compressive strength of the composite CFST columns. B and C are the conversion factors, \(\xi\) is the confining factor.

Eurocode 4 (EC4)

American code ACI 2005

Japanese code AIJ 1997

where \(A_{c}\) is the cross-sectional area of the core concrete and \(A_{s}\) is the cross-sectional area of the steel tube.

Comparison with design codes

Table 5 and Table 6 show the axial bearing capacity values of RCFST columns calculated according to different design codes. Through a comprehensive comparison of mean values, standard deviations, and coefficients of variation, it is observed that GB 50,936–2014 specifications yield more favorable predictions for circular CFST columns, while EC4 provides more accurate results for rectangular CFST columns. Therefore, the subsequent modified bearing capacity prediction formulas are developed based on these respective specifications. The degree of dispersion between calculated and experimental values is shown in Fig. 15.

Load-bearing capacity prediction formula

Based on previous research methodologies for ultimate strength calculation, this study introduces modification coefficients determined by experimental parameters, specifically addressing the effect of rubber replacement ratio, temperature, and elevated temperature duration. By revising the formulas of GB 50,936–2014 and EC4 standards, a novel predictive equation for the ultimate strength of RCFST columns after exposure to elevated temperatures was developed, comprehensively reflecting the effect of rubber replacement ratio, temperature, and elevated temperature duration on structural ultimate strength.

The comparison between experimental results and calculated results after formula modification is shown in Table 7. In Fig. 16, the experimental and calculated values demonstrate a high degree of consistency, substantiating the accuracy and rationality of the proposed formula.

-

(1).(1).

The calculation formula for the axial compressive bearing capacity of circular RCFST columns is as follows:

$$f_{sc} = K_{R} K_{T} K_{t} (1.212 + B\xi + C\xi^{2} )f_{ck}$$(10)$$K_{R} = 1.1{20 - 0}{\text{.021}}R + 0.002R^{2} - 7.667 \times 10^{ - 5} R^{3} { (0} \le R \le 20)$$(11)$$K_{T} = 0.727 + {8}{\text{.149}} \times {10}^{ - 4} T - {8}{\text{.652}} \times {10}^{ - 6} T^{2} + 2.432 \times 10^{ - 8} T^{3} - 1.779 \times 10^{ - 11} T^{4}$$$${(20} \le T \le {800)}$$(12)$$K_{t} = 0.740 - 0.008t + {1}{\text{.509}} \times {10}^{ - 4} t^{2} - 5.473 \times 10^{ - 7} t^{3} { (30} \le t \le {18}0)$$(13)$$N_{u} = A_{sc} f_{sc}$$(5) -

(2).(2).

The calculation formula for the axial compressive bearing capacity of square RCFST columns is as follows:

$$N_{u} = K_{R} K_{T} K_{t} \left( {\frac{{f_{y} }}{1.1}A_{s} + \frac{{f_{c}^{,} }}{1.5}A_{s} } \right)$$(14)$$K_{R} = 1.190 + 0.029R - {0}{\text{.008}}R^{2} + 2.900 \times 10^{ - 4} R^{3}$$$${(0} \le R \le 20)$$(15)$$K_{T} = 0.780 + 0.003T - {1}{\text{.936}} \times {10}^{ - 5} T^{2} + 4.040 \times 10^{ - 8} T^{3} - 2.500 \times 10^{ - 11} T^{4}$$$${(20} \le T \le {800)}$$(16)$$K_{t} = 0.830 - 0.008t + {1}{\text{.470}} \times {10}^{ - 4} t^{2} - 5.309 \times 10^{ - 7} t^{3}$$$${(30} \le t \le {18}0)$$(17)

where \(K_{R}\) is the rubber replacement ratio coefficient, \(K_{T}\) is the temperature coefficient, and \(K_{t}\) is the heating time coefficient.

Future prospects

With the continuous development of computer technology, numerical simulation methods have become an important analytical and predictive tool in the field of engineering. Especially the performance of composite structures under different working conditions. Guo et al.39 discussed the intrinsic models of composites (e.g., continuous damage model, cohesive damage model, mixture theory model, multiscale model, and nonorthogonal constitutive model) and their application in finite element analysis. The importance of the finite element method in the design and analysis of composite materials, especially in dealing with complex loads and damage prediction, was also emphasized. Kabir et al.40 investigated the stress analysis problem of reinforcing crack-containing epoxy resin plate with graphene nanoplatelets (GnP) and proposed a multi-step numerical method based on Bézier. This method is extended to accurately solve the governing fourth-order complex partial differential equation (PDE) in linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM) problems. The method shows effectiveness in complex geometric crack analysis and provides a new numerical tool for LEFM impact analysis of composites. In the future, we can use these powerful numerical simulation methods to validate results, analyze stress distributions, and explore untested conditions to gain a deeper understanding of the axial compression performance of RCFST columns at elevated temperatures.

Conclusion

Analyzing the experimental phenomena and the obtained results, the major conclusions are as follows:

-

(1).

The ultimate load-bearing capacity of RCFST columns diminished with higher ratios of rubber replacement following exposure to elevated temperatures. When the replacement ratio was below 10%, the stiffness exhibited negligible variation while the ductility improved as the replacement ratio increased. However, when the ratio of rubber replacement hit 20%, both the ductility and stiffness deteriorated significantly, with the ultimate load capacity declining by more than 25%. Therefore, it was advisable to limit the rubber replacement ratio to no more than 10% for practical engineering applications.

-

(2).

Elevated temperatures had a marked negative impact on the axial load-bearing ability, stiffness, and ductility of RCFST columns. As temperatures rose, there was a notable declin in ultimate load capacity, accompanied by a downward shift in the yield point. When the temperature remained below 400 °C, the axial stiffness remained essentially unchanged, and the specimens maintained satisfactory ductility under elevated temperatures.

-

(3).

The duration of exposure to elevated temperatures played a crucial role in determining the residual performance of RCFST columns. Increasing the exposure duration from 0 to 180 min resulted in further deterioration of axial load-bearing capacity, stiffness, and ductility. This time-dependent degradation underscored the significance of incorporating fire exposure duration in structural design and assessment protocols.

-

(4).

Circular RCFST columns exhibited superior performance compared to their square counterparts across all rubber replacement ratios, temperatures, and elevated temperature durations. The more uniform and effective confinement provided by circular steel tubes mitigated concrete spalling, restrained the development of thermal stresses, and enhanced overall structural integrity under elevated temperatures.

-

(5).

Based on the calculation methods prescribed in GB 50,936–2014 and EC4 specifications, a revised formula was introduced to estimate the ultimate bearing capacity of RCFST columns after exposure to elevated temperatures, incorporating influence coefficients for rubber replacement ratio, temperature, and elevated temperature duration. The predictive formula’s feasibility was validated by comparing calculated results with experimental data.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Elchalakani, M., Aly, T. & Abu-Aisheh, E. Mechanical properties of rubberised concrete for road side barriers. Aust. J. Civ. Eng. 14(1), 1–12 (2016).

Duarte, A. P. C. et al. On the sustainability of rubberized concrete filled square steel tubular columns. J. Clean. Prod. 170, 510–521 (2018).

Dong, M. et al. Behaviour and design of rubberised concrete filled steel tubes under combined loading conditions. Thin-Walled Struct. 139, 24–38 (2019).

Najim, K. B. & Hall, M. R. A review of the fresh/hardened properties and applications for plain-(PRC) and self-compacting rubberised concrete (SCRC). Constr. Build. Mater. 24(11), 2043–2051 (2010).

Zhaoyuan, Y. et al. Axial compressive behavior of square steel tube confined rubberized concrete stub columns. J. Build. Eng. 52, 104371 (2022).

Raghavan, D. Study of rubber-filled cementitious composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 77(4), 934–942 (2000).

Huang, B. et al. Investigation into waste tire rubber-filled concrete. J. Mater. Civil Eng. 16(3), 187–194 (2004).

Topcu, I. B. The properties of rubberized concretes. Cem. Concr. Res. 25(2), 304–310 (1995).

Li, Z., Li, F. & Li, J. S. L. Properties of concrete incorporating rubber tyre particles. Mag. Concr. Res. 50(4), 297–304 (1998).

Bisht, K. & Ramana, P. V. Evaluation of mechanical and durability properties of crumb rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 155, 811–817 (2017).

Mhaya, A. M. et al. Long-term mechanical and durable properties of waste tires rubber crumbs replaced GBFS modified concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 256, 119505 (2020).

Feng, W. et al. Experimental study on dynamic split tensile properties of rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 165, 675–687 (2018).

Segre, N. & Joekes, I. Use of tire rubber particles as addition to cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 30(9), 1421–1425 (2000).

Williams, K. C. & Partheeban, P. An experimental and numerical approach in strength prediction of reclaimed rubber concrete. Adv. Concr. Constr. 6(1), 87 (2018).

Guo, S. et al. Evaluation of properties and performance of rubber-modified concrete for recycling of waste scrap tire. J. Clean. Prod. 148, 681–689 (2017).

Abendeh, R., Ahmad, H. S. & Hunaiti, Y. M. Experimental studies on the behavior of concrete-filled steel tubes incorporating crumb rubber. J. Constr. Steel Res. 122, 251–260 (2016).

Silva, A. et al. Monotonic and cyclic flexural behaviour of square/rectangular rubberized concrete-filled steel tubes. J. Constr. Steel Res. 139, 385–396 (2017).

Güneyisi, E. M., Gültekin, A. & Mermerdaş, K. Ultimate capacity prediction of axially loaded CFST short columns. Int. J. Steel Struct. 16, 99–114 (2016).

Bokkhunthod, N. et al. Experimental study of cellular lightweight concrete-filled steel tube columns using hydraulic cement. Key Eng. Mater. 922, 147–152 (2022).

Wang, Ke. & Young, B. Fire resistance of concrete-filled high strength steel tubular columns. Thin-Walled Struct. 71, 46–56 (2013).

Thumrongvut, J., Tipcharoen, A. & Prathumwong, K. Post-fire performance of square concrete-filled steel tube columns under uni-axial load. Mater. Sci. Forum. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.1016.618 (2021) (Trans Tech Publications Ltd).

Li, W. et al. Mechanical behavior of recycled aggregate concrete-filled steel tube stub columns after exposure to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 146, 571–581 (2017).

JGJ55–2011. Specification for mix proportion design of ordinary concrete (China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, 2011).

GB/T50081–2019 Standard test methods for physical and mechanical properties of concrete (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Behavior of steel tube columns filled with steel-fiber-reinforced self-stressing recycled aggregate concrete under axial compression. Thin-Walled Struct. 149, 106521 (2020).

Bengar, H. A. & Shahmansouri, A. A. Post-fire behavior of unconfined and steel tube confined rubberized concrete under axial compression. Structures 32, 731 (2021).

Wang, Y.-H. et al. Axial compression performance of rubberized concrete-filled steel tubular stub columns after fire exposure: Experimental investigation and calculation models. Constr. Build. Mater. 438, 137129 (2024).

Shen, M. et al. Axial compressive behavior of rubberized concrete-filled steel tube short columns. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e00851 (2022).

Duarte, A. P. C. et al. Finite element modelling of short steel tubes filled with rubberized concrete. Compos. Struct. 150, 28–40 (2016).

Tang, Y. et al. Compressive properties of rubber-modified recycled aggregate concrete subjected to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 268, 121181 (2021).

Duarte, A. P. C. et al. Tests and design of short steel tubes filled with rubberised concrete. Eng. Struct. 112, 274–286 (2016).

Tao, Z., Wang, X.-Q. & Uy, B. Stress-strain curves of structural and reinforcing steels after exposure to elevated temperatures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 25(9), 1306–1316 (2013).

Zhong, S. T. Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures 1–5 (Tsinghua University Press, 2003).

Karimi, A. & Nematzadeh, M. Axial compressive performance of steel tube columns filled with steel fiber-reinforced high strength concrete containing tire aggregate after exposure to high temperatures. Eng. Struct. 219, 110608 (2020).

GB50936–2014. Technical Specification for Concrete-Filled Steel Tube Structures (China Architecture and Building Press, Beijing, 2014).

Eurocode 4. Design of composite steel and concrete structures - Part 1–1: General rules and rules for buildings EN 1994–1–1:2004 (CEN, Brussels, 2004).

American Concrete Institute. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary ACI 2005 (American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills MI, 2005).

Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ). Recommendations for design and construction of concrete filled steel tubular structures (Architectural Institute of Japan, Tokyo, 1997).

Guo, Q. et al. Constitutive models for the structural analysis of composite materials for the finite element analysis: A review of recent practices. Compos. Struct. 260, 113267 (2021).

Kabir, H. & Aghdam, M. M. A generalized 2D Bézier-based solution for stress analysis of notched epoxy resin plates reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets. Thin-Walled Struct. 169, 108484 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the financial support provided by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (No. 52068001), the Project of academic and technological leaders of major disciplines in Jiangxi Province (No.20204BCJL2037), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (No. 20202ACBL214017).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China,No. 52068001,Project of academic and technological leaders of major disciplines in Jiangxi Province,No.20204BCJL2037,Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province,No. 20202ACBL214017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiang Yong: Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation;Liang Jiongfeng: Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration; Wang Caisen:Conceptualization, Methodology;Wangliu Haoxiang:Software, Validation; Li Wei:Supervision, Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, Y., Liang, J., Wang, C. et al. Axial compression behavior of rubberized concrete filled steel tube columns after exposure to elevated temperatures. Sci Rep 15, 9640 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93363-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93363-0