Abstract

Ecological restoration is crucial for combatting desertification and mitigating grassland degradation. The assessment of changes in soil quality under different restoration patterns is beneficial for optimizing the development and implementation of local ecological restoration strategies. In this study, five typical restoration patterns of sample plots—plant regenerative sand-barrier land (S2), shrub planted afforested land (S3), aerially seeded afforested land (S4), artificially restored grassland (S5), fenced shrubland (S6), and a control plot (S1)—were selected as research objects in the Horqin sandy area. Four depths of soil samples ranging from 0 to 30 cm were collected from six plots to determine their physicochemical properties, analyze soil primary particle size and nutrient levels in different plots, and propose a soil quality index (SQI) to evaluate the effectiveness of soil restoration under different restoration patterns. The results showed a decrease in sand content under the five restoration patterns, whereas clay and silt content, soil fractal dimension (D value), and SQI increased significantly (P < 0.05). The soil fractal dimension was positively correlated with the contents of clay, slit, and the SQI (P < 0.01). The composite soil quality index from highest to lowest was S6 (0.5877) > S5 (0.5384) > S4 (0.4357) > S3 (0.4068) > S2 (0.1305) > S1 (0.0648). The soil restoration effects were greatest for S5 in the 0–10 cm soil depth, and the soil restoration effects were most effective for S6 in the 10–30 cm soil depth, with SQIs increasing by 11.21 and 7.85 times, respectively, compared with that of the control sample plot. Based on the results at different soil depths, we believe that the restoration pattern of artificially planting shrub-grass combined with fencing may significantly enhance restoration effectiveness on sandy land.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aeolian desertification, soil erosion, and salinization have become prominent issues under the influence of human disturbance and climate change1. Desertification poses threats, such as ecological imbalances, reduced productivity, and sandstorms, to arid and semiarid zones2,3. The Mu Us, Hunshandake, Horqin, and Hulun Buir sandy areas are the four largest sandy areas in China. One of the main types of desertification in northern China is aeolian desertification4. Mitigating the worsening of desertification is an important aspect of ecological restoration to achieve balanced ecological development5. The “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Prevention and Control of Desertification” was promulgated and implemented on 2001 to support the planning, implementation, and completion of desertification control projects. China has made significant progress in desertification prevention and control through the construction of ecological engineering systems such as natural resource protection, the return of farmland to forests and grasslands, Beijing-Tianjin sand source treatment, and the Three-North shelterbelt project. According to the latest desertification and sand monitoring survey, China’s desertification land area was 2.5737 million km2, and the aeolian desertification land area was 1.6878 million km2, which are 1.84% and 2.21% lower, respectively, than the first desertification and desertification monitoring in 1994.

Aeolian desertification leads to soil nutrient loss, disrupts ecosystem stability, reduces land resource availability, and hinders socioeconomic development6. Addressing land desertification requires developing effective ecological restoration measures to mitigate vegetation degradation and soil erosion7. Sand barriers are highly effective in fixing sand during the initial stages of sand restoration8. Artificial vegetation restoration also plays an important role in controlling desertification and restoring soil quality in arid and semiarid areas9,10. Studies have indicated that fencing reduces human disturbance, thereby altering soil texture and enhancing vegetation growth11. Long-term fencing is conducive to increasing the soil total nitrogen, carbon, and phosphorus12. Various ecological restoration measures have been implemented in China, such as sand barriers, aerial seeding afforestation, artificial planting of forest-shrub-grass, and fence enclosures, to mitigate desertification and restore ecosystems. However, evaluating the effectiveness of sand restoration measures and formulating sustainable recovery strategies remains major challenges13. Evaluating changes in soil quality under various restoration patterns is crucial for assessing ecological restoration effectiveness14,15.

Important indices for evaluating soil quality include soil texture and fertility. Specifically, the primary particle size of the soil has a significant effect on soil pore space16. Soil aeration and water permeability change with soil primary particle size distribution (PSD), which affects soil nutrient availability and plant growth17. Soils of different particle sizes differ in their ability to retain nutrients. Organic matter and nutrients are more likely to adhere to clay particles18.The Loss of nutrient-rich fine particles exacerbates soil erosion19,20. Based on fractal theory21,22, relevant studies have revealed the relationship between soil primary particle size distribution and soil nutrients by measuring the soil fractal dimension23,24. Studies have shown that soil quality and erosion sensitivity are highly correlated with soil fractal dimension (D)25, with more severe land degradation producing a lower D value26. Important indicators of soil fertility include soil organic matter (SOM), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K)27. The physicochemical properties of soil and vegetation growth during restoration are interdependent and mutually restrictive. The secretions and litters of plants can provide nutrients for soil microorganisms, thereby affecting the transformation of soil organic matter and nutrient accumulation. These changes in soil properties in turn affect plant growth28. Moreover, in the process of vegetation restoration, the direct interpenetrating action of the root system and the indirect effect produced by the decomposition of litter increase the stability of the soil structure, which becomes less susceptible to erosion and thus improves the soil texture29. Different restoration patterns may affect changes in soil PSD and the accumulation and distribution of nutrients30. Changes in soil properties are also important factors affecting vegetation restoration31. Some studies have provided evidence that ecological restoration measures can successfully improve plant growth status32. Gou et al.33 found that planting artificial turf in subhumid deserts increased soil nutrient and enzyme activity. Zhang et al. 34 found that different restoration patterns, such as planting forests and grass, increased the sequestration of soil carbon and nitrogen. Therefore, the effectiveness of different restoration methods in mitigating desertification can be reflected by studying variations in soil primary particle size and nutrients during ecological restoration.

The impact of ecological restoration on soil properties is a primary focus of ecological restoration research. however most studies have emphasized the impact of various vegetation types on soil nutrients rather than different restoration patterns on soil physical and chemical properties. Additionally, regional ecological restoration assessments often prioritize indicators such as vegetation coverage and biomass, neglecting soil fractal dimension and nutrient content. Limited field monitoring data on soil significantly affects the accuracy of restoration effectiveness assessments, especially in the Horqin sandy Area under different restoration patterns. The following hypotheses are proposed regarding the aforementioned issues: (1) the primary particle size distribution of 0–30 cm soil layer in sandy land changed under different restoration patterns such as sand barrier, artificial grass planting, shrub afforestation and fencing, and a correlation exists between soil fractal dimension and soil nutrients content; (2) diverse restoration patterns for sandy land exhibit significantly different impacts on soil nutrients content, and these effects demonstrate specific patterns at varying soil depths. In order to text the hypotheses this study aims to: (1) evaluate the response of soil primary particle size distribution and nutrients content in the five restoration patterns of sandy land, such as plant regenerative sand-barrier land, shrub planted afforested land, aerially seeded afforested land, artificially restored grassland, and fenced shrubland; (2) identify differences in the soil fractal dimension and nutrients content under the five restoration patterns, develop a soil quality index, and analyze the impact of different restoration patterns on soil improvement in the Horqin sandy area. Our results are expected to contribute to identify the most suitable ecological restoration patterns for sandy land, and provide empirical evidence for the development of sustainable environmental conservation and rehabilitation strategies.

Materials and methods

Research area

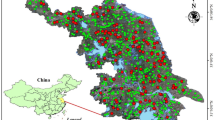

The research area is situated in Bahrain Right Banner west of the Horqin sandy area, 118°15′–120°05′ E, 43°12′–44°27′ N (Fig. 1). This is one of the key areas in the Beijing–Tianjin sand source control area in China. The northwestern region has undulating mountains and severe desertification, whereas the southeastern region is relatively flat. The average elevation is approximately 500 m. West of the Horqin sandy area lies an extensive distribution of stationary dunes, positioned in the transition zone from the northeastern plain to the Inner Mongolia Plateau. The climate transitions from temperate to semihumid and semiarid zones, featuring favorable light conditions and a temperate continental monsoon climate. It has a dry spring and winter, with rainfall and temperature rising simultaneously, mainly in July and August. The average annual temperature is 5.2–6.4 °C, and the average annual precipitation is 350 mm. The soil type is kastanozems according to the FAO90 soil classification. The perennial vegetation of sandy lands consists mainly of Caragana microphylla, Artemisia wudanica, Artemisia frigida, Artemisia desertorum, and Agropyron cristatum35.

Selection of sample sites

Based on factors such as vegetation type, topography, slope, and aspect, the sample sites were arranged along the sand belt in the western margin of Horqin. In accordance with the different ecological restoration measures of local sandy land, five typical representative sample sites were selected in restored areas that had been rehabilitated for ten years. A control plot was selected in the unrestored areas. Three replicates were used for each plot. Basic information regarding the sample sites is provided in Table 1.

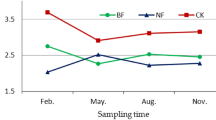

Soil sample test

Three quadrats were set under different sample plots as replicates, and five sampling points were used in the diagonal method to collect soil samples from five soil layers in the soil profile: 0–5 cm (a), 5–10 cm (b), 10–20 cm (c), and 20–30 cm (d). The soil samples were collected in sampling bags for further testing in the laboratory. To assess the effects of soil quality restoration under different ecological restoration patterns, soil PSD, pH, SOM, and nutrient content were selected for analysis (Fig. 2).

The soil PSD was measured using a Coulter LS230 laser particle size analyzer. Particles between 0.05 and 2 mm were classified as sand, those between 0.002 and 0.05 mm were classified as silt, and those less than 0.002 mm were classified as clay. The pH was determined using the potentiometric method, and the SOM content was determined using the concentrated sulfuric acid‒potassium dichromate oxidation method. Total nitrogen (TN) was determined using the Kjeldahl method, total phosphorus (TP) was determined using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer, and total potassium (TK) was determined using an atomic absorption spectrometer. The alkali‒diffusion method was adopted to determine hydrolyzed nitrogen (HN), the molybdenum anticolorimetric method was used to determine available phosphorus (AP), and the ammonium acetate extraction‒ICP method was used to determine available potassium (AK).

Statistical analysis

In this study, an improved soil fractal model was used to calculate the fractal dimensions (D) of soil at different soil depths36. The formulas are as follows:

After the formula conversion,

where \(\:M\left(\delta\: < {\bar d_i} \right)\) is the cumulative mass of particles smaller than \(\:{d}_{i},\:{M}_{0}\) is the sum of the mass for each particle size, \({\bar d_i}\) represents the average particle size between two adjacent fractions \(\:{d}_{i}\) and \(\:{d}_{i+1},\:{\bar d_i}=\left({d}_{i}+{d}_{i+1}\right)/2{(d}_{i}>{d}_{i+1}, \;\; i=1, 2,3\dots\:)\), and \({\bar d_{max}}\) is the average size of the largest particles. The SQI was used to represent the soil nutrient status and was calculated via the following steps:

-

1.

Index normalization.

$$\:{X}^{{\prime\:}}=\frac{X-{X}_{min}}{{X}_{max}-{X}_{min}} \; (\text{Positive index})$$(3)where \(\:{X}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the normalized value of the soil property index and where \(\:{X}_{min}\:\) and \(\:{X}_{max}\) are the minimum and maximum values of \(\:X\), respectively.

-

2.

Proportion of index \(\:j\) in the sample plot \(\:i\)

.

$$\:{Y}_{ij}=\frac{{X}_{ij}^{{\prime\:}}}{\sum\:_{i=1}^{m}{X}_{ij}^{{\prime\:}}}$$(4)where \(\:{Y}_{ij}\) is the proportion of index \(\:j\) in sample plot \(\:i,\:\:{X}_{ij}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the normalized value of index \(\:j\) in sample plot \(\:i,\) and m is the number of plot types.

-

3.

Weight of each index.

$$\:{e}_{j}=-k\sum\:_{i=1}^{m}({Y}_{ij}\times\:\text{ln}{Y}_{ij})$$(5)$$\:k=1/\text{ln}m$$(6)$$\:{d}_{j}=1-{e}_{j}$$(7)$$\:{W}_{i}={d}_{j}/\sum\:_{j=1}^{n}{d}_{j}$$(8)where \(\:{e}_{j}\) is the information entropy of index \(\:j\), \(\:{d}_{j}\) is the information entropy redundancy of index \(\:j\), \(\:{W}_{i}\) is the weight of the index, and \(\:j\) is the number of indices.

-

4.

Comprehensive calculation of SQI

$$\:SQI={W}_{i}\times\:{X}_{ij}^{{\prime\:}}$$(9)where \(\:{X}_{ij}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the normalized value of index \(\:j\) in sample plot \(\:i\). The indexes include SOM, TN, TP, TK, HN, AP, and AK.

The experimental data were sorted preliminarily using Excel. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple significance comparison were performed using SPSS software (version 21.0) (significance level was set at P < 0.05). Graphs were plotted using SigmaPlot 12.5 and R-v.4.3.2, and the chart data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Soil PSD and fractal dimensions of different restoration patterns

The overall distribution of the soil primary particle size composition is shown in Table 2. The highest proportion of soil particles in each plot was sand, followed by silt and clay. Compared with those in the control plots, the soil silt and clay contents in the different restoration patterns were increased in the restoration plots. The clay content decreased in the following order: S5 artificially restored grassland (2.00%) > S6 fenced shrubland (1.96%) > S4 aerially seeded afforested land (1.84%) > S3 shrub planted afforested land (1.00%) > S2 plant regenerative sand-barrier land (0%) = S1 control plot (0%). The silt content was ranked as follows: S3 shrub planted afforested land (29.54%) > S5 artificially restored grassland (5.73%) > S4 aerially seeded afforested land (5.59%) > S6 fenced shrubland (4.99%) > S2 plant regenerative sand-barrier land (4.17%) > S1 control plot (2.88%). The rank order of sand content and silt content in each plot was reversed, with the shrub planted afforested land plot having the lowest sand content (69.46%) and the control plot having the highest sand content (97.12%).

The soil fractal dimensions of the sample plots under different remediation patterns were calculated based on different soil particle–mass ratios (Table 2). The D value of the sample soils ranged from 1.66 to 2.20, which was slightly lower than that of sandy soils in China (1.834–2.641)37. Fig. 3 shows the variation in fractal dimension at different soil depths. The D values of the control sample plots were lowest (1.66–1.67) in the a to c soil layers, which were significantly lower than that in the d soil layer (2.07). The D value of plant regenerative sand-barrier land plot was significantly higher than that of control plot in the a to c soil layers, which ranged from 1.79 to 1.88, but it decreased to 1.69 in the d soil layer. Shrub planted afforested land plot had minor variation in D values from the a to d soil layers, ranging from 2.02 to 2.09. The D values of aerially seeded afforested land increased with increasing depth of the soil layer, ranging from 1.95 to 2.20. The D values of artificially restored grassland and fenced shrubland plots both decreased in layer c and increased in layer d, which were 2.00–2.13 and 1.94–2.11, respectively.

Variation in soil properties under different restoration patterns

Distribution characteristics of soil properties at various soil depths

The soil pH of the different plots ranged from 6.81 to 8.29, i.e., from neutrality to alkalinity, based on the Chinese soil pH classification standard (Fig. 4). SOM content is a key index that affects soil properties. According to the second national soil survey soil fertility status classification standard, the SOM content of the control plot was very low and decreased with increasing depth, measuring only 0.18–0.92 g/kg. The change trends of SOM content in the different soil layers of plant regenerative sand-barrier land and shrub planted afforested land plots were similar to that found in control plot. However, the SOM content in shrub planted afforested land plot increased more than that in plant regenerative sand-barrier land plot. The SOM contents of aerially seeded afforested land and artificially restored grassland plots decreased from soil layer a to c and increased in the d soil layer, reaching 3.55–17.78 g/kg and 9.00–15.59 g/kg, respectively. The SOM content in fenced shrubland plot increased with soil depth, ranging from 10.39 to 18.26 g/kg. Significant differences were found in the SOM of each soil layer among the different restoration patterns (Fig. 4). Artificially restored grassland had the highest SOM content in soil layers a and b, while the highest SOM content in soil layer c and d was found in fenced shrubland.

Variation in pH and SOM content at four soil depths under different restoration patterns. S1: Control plot; S2: Plant regenerative sand-barrier land; S3: Shrub planted afforested land; S4: Aerially seeded afforested land; S5: Artificially restored grassland; S6: Fenced shrubland. Differences in values for the same soil depth between plots are indicated by different lowercase letters (P < 0.05). Differences in values within sample plots at different soil depths are indicated by different uppercase letters (P < 0.05). An analysis of variance was performed using Duncan’s new multiple-range test.

The soil nutrient contents of the sample plots differed significantly under the different restoration patterns (Fig. 5). Except for the plant regenerative sand-barrier land, the total nitrogen content of each restoration site significantly increased compared with that of the control plot. The total contents of phosphorus and potassium in plant regenerative sand-barrier land and shrub planted afforested land plots did not change significantly compared with those in control plot, but changes were obvious in aerially seeded afforested land, artificially restored grassland, and fenced shrubland plots. The total phosphorus and potassium contents in aerially seeded afforested land and artificially restored grassland plots, first decreased but then increased as the soil depth increased. The total nitrogen and phosphorus contents of fenced shrubland plot increased with increasing soil depth. However, the total potassium contents in aerially seeded afforested land, artificially restored grassland, and fenced shrubland plots did not significantly change with increasing soil depth.

The contents of available nutrients, such as HN, AP, and AK, in the sample plots under each restoration pattern were significantly increased in soil layer a (P < 0.05). In soil layer b, the HN and AK contents increased under all the restoration patterns except plant regenerative sand-barrier land, whereas the AP content significantly increased in plant regenerative sand-barrier land, shrub planted afforested land, artificially restored grassland, and fenced shrubland plots. In soil layer c, the HN content increased significantly in the shrub planted afforested land, aerially seeded afforested land, and artificially restored grassland plots, whereas both the AP and AK contents were greatest in fenced shrubland plot. The surface accumulation of available nutrients in plant regenerative sand-barrier land, shrub planted afforested land, and artificially restored grassland, was greater than those in the other restoration patterns, whereas fenced shrubland and aerially seeded afforested land had greater effects on the AP and AK contents in soil layers c and d, respectively.

Variation in nutrient content at four soil depths under different restoration patterns. S1: Control plot; S2: Plant regenerative sand-barrier land; S3: Shrub planted afforested land; S4: Aerially seeded afforested land; S5: Artificially restored grassland; S6: Fenced shrubland. Differences in values for the same soil depth between plots are indicated by different lowercase letters (P < 0.05). Differences in values within sample plots at different soil depths are indicated by different uppercase letters (P < 0.05). An analysis of variance was performed using Duncan’s new multiple-range test.

Soil quality index (SQI)

Owing to the interdependent relationships among soil characteristics, individual soil properties cannot be accurate indicators of soil quality. To assess the soil quality changes in the sample plots under different restoration patterns, seven nutrients were used as indicators, and the indicator values of the four soil depths were normalized separately. The corresponding weights were determined using the entropy method (Table 3) to calculate the SQI. The profile distributions of the SQI values for different restoration patterns are shown in Fig. 6. The SQI index ranges from 0 to 1. Based on the SQI, the soil nutrient level was categorized into five levels ranging from low to high. In control plot, the SQI values were 0.0325, 0.0728, 0.0938, and 0.0601 for soil layers a to d, respectively. The nutrient levels were classified as very low. The soil quality index varied significantly among plots under different restoration patterns. In soil layer a, the ranking of soil quality index was S5 (0.6494) > S3 (0.4731) > S6 (0.4551) > S4 (0.4159) > S2 (0.2248). In soil layer b, the ranking was S5 (0.6368) > S6 (0.5333) > S3 (0.5202) > S4 (0.3577) > S2 (0.1241); in soil layer c, the ranking was S6 (0.7469) > S5 (0.3726) > S3 (0.3429) > S4 (0.2204) > S2 (0.0895); and in soil layer d, the ranking was S4 (0.7489) > S6 (0.6157) > S5 (0.4948) > S3 (0.2909) > S2 (0.0837). Compared with that of the control land samples, the SQIs of the samples from the five restoration patterns improved, with the average SQI values ranked as follows: S6 (0.5877) > S5 (0.5384) > S4 (0.4357) > S3 (0.4068) > S2 (0.1305) > S1 (0.0648). The soil quality indices of the S3–S6 restoration patterns were significantly greater than that of control plot, and reached an intermediate level. The restoration effect of artificially restored grassland was greatest at 0–10 cm, that of fenced shrubland was greatest at 10–20 cm, and that of aerial seeded afforested land was greatest at 20–30 cm.

Variation in SQI values at four soil depths under different restoration patterns. S1: Control plot; S2: Plant regenerative sand-barrier land; S3: Shrub planted afforested land; S4: Aerially seeded afforested land; S5: Artificially restored grassland; S6: Fenced shrubland. Differences in values for the same soil depth between plots are indicated by different lowercase letters (P < 0.05). Differences in values within sample plots at different soil depths are indicated by different uppercase letters (P < 0.05). An analysis of variance was performed using Duncan’s new multiple-range test.

Relationships among soil nutrients, PSD, fractal dimension, and SQI

The relationships among soil nutrients content, primary particle size distribution, fractal dimension, and soil quality index were evaluated using the Spearman correlation test. The results are presented in Fig. 7, which shows that the contents of soil silt, clay, SOM, TN, TP, HN, and AK increased with decreasing sand content. The increase in silt content was correlated with a decrease in the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N). The silt and clay contents were significantly positively correlated with the contents of various nutrients in the soil. The D values increased with decreasing soil sand content and were positively correlated with soil slit and clay contents as well as SOM, TN, TP, HN, and AK contents. Significant positive correlations were also found between SOM and TN, TP, TK, HN, and AK (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the results showed positive correlations between the SQI value and the following parameters: SOM, TN, TP, TK, HN, AK, clay, and D values. Conversely, a negative correlation was observed between the SQI value and sand content. Under different restoration patterns, sand contents decreased while clay contents increased in the Horqin sandy area soil, enhancing nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium accumulation and bioavailability. This improvement in soil nutrients reduced the potential risk of erosion.

Correlation heatmap of the soil physicochemical properties, PSD, and SQI. SOM: soil organic matter; TN: total nitrogen; TP: total phosphorus; TK: total potassium; C/N: organic carbon/total nitrogen; HN: alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen; AP: available phosphorus; AK: rapidly available potassium; sand: soil particles of 0.05–2 mm; silt: soil particles of 0.002–0.05 mm; clay: soil particles below 0.002 mm; D: soil fractal dimension; SQI: soil quality index. **level of significance is 0.01; *level of significance is 0.05.

Discussion

The implementation of ecological restoration measures on degraded land helps to protect and restore local ecosystems. Restoration also promotes the accumulation of soil nutrients by altering their distribution and cycling in the soil38. The results of the experiment showed that the soil physicochemical properties of the sampled sites varied, indicating that different types of remediation measures had important effects on the changes in soil primary particle size and nutrients. Compared with those in the control plot, the soil sand contents decreased under the five restoration patterns, whereas the contents of clay and silt increased, which is consistent with the findings of Wang et al39. Increases in silt and clay contents and decreases in sand content are beneficial for the accumulation of soil nutrients. The enrichment of organic matter and nitrogen increases the proportion of soil aggregates and provides energy and nutrition to soil microorganisms40,41. The formation of soil aggregates has the dual benefit of reducing soil erosion and providing nutrients to plant roots42,43. An increase in the soil fractal dimension can reflect an improvement in soil quality44,45. The fractal dimension of the surface soil increased in the five restoration samples, indicating varying degrees of decrease in land desertification.

In addition to plant regenerative sand-barrier land, SOM, TN, and TP increased significantly in the restoration plots, similar to the implementation effects of typical ecological restoration measures in sandy land reported by Hu (2021)46. The contents of SOM, TN, and TP in the artificially restored grassland plots were highest in soil layers a and b, whereas fenced shrubland plots were highest in soil layers c and d. However, the content of TK did not vary significantly across the different soil layers. Among different restoration patterns, only aerially seeded afforested land, artificially restored grassland, and fenced shrubland plots showed a slight increase in TK contents. This pattern may occur because 98% of the potassium in the soil exists as mineral potassium, which is largely dependent on the parent material of the region. These results indicate that the hierarchical structure of soil nutrient accumulation in sandy land under different ecological restoration patterns significantly differed.

The available nutrients HN, AP, and AK significantly accumulated in layer a of the soil surface in the plant regenerative sand-barrier land and shrub planted afforested land. This may be because the sand barrier effectively increases the surface roughness and physical stability of the sand particles, thereby reducing the occurrence of wind erosion47. The beneficial effect of sand barriers on soil function is achieved by increasing the microbial activity of the soil, a process that may require several years of sand barrier aging48. Therefore, available nutrients were higher in the sand barrier restoration sample plot than in the control plot, but the total nutrient accumulation was lower in the sand barrier restoration plot than in the other restoration patterns. Shrub planted afforested land presented significantly higher HN levels than did the other four restoration patterns. This difference may be due to an increase in litter accumulation on the soil surface resulting from herb and shrub colonization. The amount of litter deposited by shrubs was several times greater than that deposited by herbs, leading to a greater potential for nutrient input. The input of plant litter reduces soil pH and accelerates soil extracellular enzyme activity, which promotes the active transformation of nutrients49. The HN content also increased in aerially seeded afforested land, artificially restored grassland, and fenced shrubland, but the differences between these treatments were not significant. The AP and AK contents decreased with increasing soil depth in the artificially restored grassland plot, whereas an inflection point occurred in layers c to d in the aerially seeded afforested land and fenced shrubland plots. There was a gradual decrease in the AP and AK contents in layers a to c in the aerially seeded afforested land plot but a steep increase in layer d. The AP and AK contents in the fenced shrubland plot were highest in layer c and declined in layer d. This may occur because variation in vegetation restoration among aerially seeded afforested land, artificially restored grassland, and fenced shrubland. Artificially restored grasslands are dominated by herbaceous plants, which can form more abundant fine roots on the soil surface to promote agglomerate formation and enhance microbial activity50,51. As a result, the AP and AK contents of artificially restored grassland were relatively higher in layers a and b. Fencing can prevent interference from human activities, promote vegetative propagation, and increase plant species richness11. There was more shrub vegetation in the aerially seeded afforested land and fenced shrubland restoration patterns. Compared with herbaceous plants, shrub roots are thicker and more widely distributed, which can affect the properties of deep soil. In addition, the shrub canopy can reduce water evaporation from the soil surface and enhance ground infiltration, thereby promoting microbial activity in deep soil. Therefore, aerially seeded afforested and fenced shrubland had higher available nutrient levels in deeper soils compared to other plots.

Conclusions

By comparing and evaluating the improvements in soil primary particle size and nutrient levels in the Horqin sandy area under different restoration patterns, artificially restored grassland (S5) had the most positive effect on the top layer of soil (within 10 cm), and fenced shrubland (S6) had the greatest effect on deeper soil (between 10 and 30 cm). The results showed that ecological restoration was an effective means of improving the soil quality of the Horqin sandy area. Herbaceous planting improved the surface soil, whereas shrub planting had a more pronounced impact on the restoration of deep soil. Additionally, fence enclosures remain an effective management measure for vegetation restoration in sandy areas. Therefore, in the ecological restoration of the Horqin sandy area, the shrub–grass planting pattern combined with fencing should be considered for restoring degraded land. Long-term quantitative research on the effects of sandy land restoration is still needed to reveal the specific mechanisms of vegetation‒soil interactions and to optimize ecological restoration strategies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

UNCCD. United Nations Convention To Combat Desertification in those Countries Experiencing Serious Drought And/or Desertification, Particularly in Africa, 1–2 (United Nations Environment Programme for the Convention to Combat Desertification (CCD), 1994).

Dong, Z., Hu, G., Yan, C., Wang, W. & Lu, J. Aeolian desertification and its causes in the Zoige plateau of China’s Qinghai–Tibetan plateau. Environ. Earth Sci. 59, 1731–1740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-009-0155-9 (2010).

Wang, G., Munson, S. M., Yu, K., Chen, N. & Gou, Q. Ecological effects of establishing a 40-year Oasis protection system in a Northwestern China desert. Catena 187, 104374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2019.104374 (2020).

Tao, W. Progress in sandy desertification research of China. J. Geog. Sci. 14, 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02837482 (2004).

Wang, X., Chen, F., Hasi, E. & Li, J. Desertification in China: an assessment. Earth Sci. Rev. 88(3–4), 188–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2008.02.001 (2008).

Zhang, N. et al. Change of soil physicochemical properties, bacterial community and aggregation during desertification of grasslands in the Tibetan plateau. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 72(1), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12939 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Response of soil enzyme activity to long-term restoration of desertified land. Catena 133, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2015.04.012 (2015). (2015).

Liu, L. & Bo, T. Effects of checkerboard sand barrier belt on sand transport and Dune advance. Aeolian Res. 42, 100546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeolia.2019.100546 (2020).

Diasso, U. & Abiodun, B. J. Future impacts of global warming and reforestation on drought patterns over West Africa. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 133, 647–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-017-2209-3 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Nature-based framework for sustainable afforestation in global drylands under changing climate. Glob. Change Biol. 28(7), 2202–2220. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16059 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. Effects of fence enclosure on vegetation community characteristics and productivity of a degraded temperate meadow steppe in Northern China. Appl. Sci. 10(8), 2952. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10082952 (2020).

Wu, G., Liu, Z., Zhang, L., Chen, J. & Hu, T. Long-term fencing improved soil properties and soil organic carbon storage in an alpine swamp meadow of Western China. Plant. Soil. 332, 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-010-0299-0 (2010).

Dong, S., Shang, Z., Gao, J. & Boone, R. B. Enhancing sustainability of grassland ecosystems through ecological restoration and grazing management in an era of climate change on Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 287, 106684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.106684 (2020).

Liao, C. et al. Can ecological restoration improve soil properties and plant growth in valley-slope dunes on Southern Tibetan plateau?? Phys. Geogr. 42(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723646.2020.1735859 (2021).

Hu, J., Zhou, Q., Cao, Q. & Hu, J. Effects of ecological restoration measures on vegetation and soil properties in semi-humid sandy land on the Southeast Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, China. Global Ecol. Conserv. 33, e02000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2022.e02000 (2022).

Zuo, F. et al. Soil particle-size distribution and aggregate stability of new reconstructed purple soil affected by soil erosion in overland flow. J. Soils Sediment. 20, 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02408-1 (2020).

Li, H., Dang, X., Han, Y., Qi, S. & Meng, Z. Sand-fixing measures improve soil particle distribution and promote soil nutrient accumulation for desert–Yellow river coastal Ecotone, China. Ecol. Ind. 157, 111239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.111239 (2023).

Janzen, H., Campbell, C. A., Brandt, S. A., Lafond, G. P. & Townley-Smith, L. Light-fraction organic matter in soils from long‐term crop rotations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 56(6), 1799–1806. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1992.03615995005600060025x (1992).

Zhao, H. et al. Effects of desertification on soil organic C and N content in sandy farmland and grassland of inner Mongolia. Catena 77(3), 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2008.12.007 (2009).

Noma Adamou, S., Abdourhamane Touré, A. & Daoudi, L. Effects of restoration of degraded lands on soils physicochemical properties and adaptability of planted Woody species in Southwestern Niger. Land. Degrad. Dev. 33(18), 3938–3953. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4435 (2022).

Mandelbrot, B. How long is the Coast of Britain? Statistical self-similarity and fractional dimension. Science 156(3775), 636–638. https://doi.org/10.1126/Science.156.3775.636 (1967).

Turcotte, D. L. Fractals and fragmentation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth, 91(B2), 1921–1926. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB091iB02p01921 (1986).

Rieu, M. & Sposito, G. Fractal fragmentation, soil porosity, and soil water properties: I. Theory. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 55(5), 1231–1238. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1991.03615995005500050006x (1991).

Rieu, M. & Sposito, G. Fractal fragmentation, soil porosity, and soil water properties: II. Applications. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 55(5), 1239–1244. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1991.03615995005500050007x (1991).

Qi, F. et al. Soil particle size distribution characteristics of different land-use types in the Funiu mountainous region. Soil. Tillage Res. 184, 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2018.06.011 (2018).

Feng, X., Qu, J., Tan, L., Fan, Q. & Niu, Q. Fractal features of sandy soil particle-size distributions during the rangeland desertification process on the Eastern Qinghai-Tibet plateau. J. Soils Sediments. 20, 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02392-6 (2020).

Mariotte, P. et al. Plant-soil feedback: bridging natural and agricultural sciences. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.11.005 (2018).

Wang, L., Zhou, G., Zhu, X., Gao, B. & Xu, H. Effects of litter on soil organic carbon and microbial functional diversity. Acta Ecol. Sin. 41(7), 2709–2718. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb202005141233 (2021).

Wu, G., Zhang, M., Liu, Y. & López-Vicente, M. Litter cover promotes biocrust decomposition and surface soil functions in sandy ecosystem. Geoderma 374, 114429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114429 (2020).

Guo, X., Yang, G., Ma, Y. & Qiao, S. Effects of different sand fixation plantations on soil properties in the Hunshandake sandy land, Eastern inner Mongolia, China. Sci. Rep. 14, 27904. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78949-4 (2024).

Li, X., Zhang, Z., Zhang, J., Wang, X. & Jia, X. Association between vegetation patterns and soil properties in the southeastern Tengger desert, China. Arid Land. Res. Manage. 18(4), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/15324980490497429 (2004).

Huang, C., Zeng, Y., Wang, L. & Wang, S. Responses of soil nutrients to vegetation restoration in China. Reg. Envriron. Chang. 20(3), 82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01679-6 (2020).

Gou, X. et al. The effect of artificial vegetation recovery on the soil nutrients and enzyme activities in subhumid desert land on the Southeast Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, China. Ecol. Eng. 139, 105528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2019.06.023 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Conversion of farmland to forest or grassland improves soil carbon, nitrogen, and ecosystem multi-functionality in a subtropical karst region of Southwest China. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 17745. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68883-w (2024).

Bai, Z. Bahrain Youqi land use planning of ecological evaluation research. Inner Mongolia Normal Univ. (2011). (in Chinese).

Yang, P., Luo, X. & Shi, Y. Soil fractal characteristics characterized by weight distribution of particle size. Chin. Sci. Bull. 20, 1896–1899. https://doi.org/10.1360/csb1993-38-20-1896 (1993). (in Chinese).

Li, D. & Zhang, T. Fractal features of particle size distribution of soils in China. Soil. Environ. Sci. 9(4), 263–265 (2000). (in Chinese).

Li, Y., Cui, J., Zhang, T., Okuro, T. & Drake, S. Effectiveness of sand-fixing measures on desert land restoration in Kerqin sandy land, Northern China. Ecol. Eng. 35(1), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.09.013 (2009).

Wang, X. et al. Multifractal dimensions of soil particle size distribution reveal the erodibility and fertility of alpine grassland soils in the Northern Tibet plateau. J. Environ. Manage. 315, 115145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115145 (2022).

Tisdall, J. M. & OADES, J. M. Organic matter and water-stable aggregates in soils. J. Soil Sci. 33(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.1982.tb01755.x (1982).

Zhou, Y. et al. Response of soil aggregate stability and erodibility to different treatments on typical steppe in the loess plateau, China. Restor. Ecol. 30(5), e13593. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13593 (2022).

Li, W. et al. The effects of simulated nitrogen deposition on plant root traits: a meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 82, 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.01.001 (2015).

Dong, L. et al. Effects of vegetation restoration types on soil nutrients and soil erodibility regulated by slope positions on the loess plateau. J. Environ. Manage. 302, 113985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113985 (2022).

Zhao, W., Liu, Z. & Cheng, G. Fractal dimension of soil particle for sand desertification. Acta Pedol. Sin. 39(6), 877–881 (2002). (in Chinese).

Liu, Z. et al. Fractal dimension characteristics of soil particle size under different plant communities in ecological restoration area. Chin. J. Ecol. 36(2), 303–308. https://doi.org/10.13292/j.1000-4890.201702.030 (2017). (in Chinese).

Hu, J. Influence of three typical ecological restoration measures on vegetation-soil system in sandy land of Northwest Sichuan. Southwest. Minzu Univ. https://doi.org/10.27417/d.cnki.gxnmc.2021.000275 (2021). (in Chinese).

Wang, Y. et al. Sand Dune stabilization changes the vegetation characteristics and soil seed bank and their correlations with environmental factors. Sci. Total Environ. 648, 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.093 (2019).

Liang, Y. et al. Natural degradation process of Salix psammophila sand barriers regulates desert soil microbial biomass C: N: P stoichiometry and homeostasis. Catena 222, 106880. (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Contributions of plant litter to soil microbial activity improvement and soil nutrient enhancement along with herb and shrub colonization expansions in an arid sandy land. Catena 227, 107098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107098 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Effects of vegetation type, fine and coarse roots on soil microbial communities and enzyme activities in Eastern Tibetan plateau. Catena. 194, 104694 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104694 (2020).

Lin, Y. et al. Leymus chinensis resists degraded soil stress by modulating root exudate components to attract beneficial microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 13, 951838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.951838 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank SNAS (www. authorservices.springernature.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Open Fund Proiect of National Key Laboratory of Ecoloeical Process and Function Assesment of Environmental Protection Reion. China(2022YSKY-08)and National key R & D plan (grant numbers: 2021YFB3901104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. provided ideas, collected the soil sample, and edited the manuscript; X.N. analyzed the data and wrote the main manuscript; W.W. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; C.F. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, X., Tian, M., Feng, C. et al. Soil quality changes in the Horqin sandy area under different ecological restoration patterns. Sci Rep 15, 8949 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93405-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93405-7