Abstract

Owing to the growing interest in the environmental impacts and energy security associated with traditional electrical energy sources, the renewable energy sources (RESs) integration of, particularly in distribution networks, is becoming increasingly urgent. Due to their decentralized characteristics, RESs have the ability to improve distribution system performance and efficiency by enhancing energy security, reliability and independence. However, the integration of RESs may influence the steady-state operation of the distribution network. Accordingly, an assessment of the impact of the high RESs integration such as wind and photovoltaic micro sources on a low-voltage (LV) radial distribution network within the Tunisia’s Sfax-North distribution network is presented in this study. To carry this out, RESs are modelled and incorporated into the power flow problem of the studied network, and then a backward/forward sweep-based technique implemented in the MATLAB environment is adopted for its implementation. This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of the impact of integrating RESs on key technical parameters of a real LV distribution network, including voltage profiles, branch currents, active and reactive power flows, and total power losses. This analysis is based on extensive simulation studies across various operating conditions and a comparative study of existing works. The simulation results reveal that appropriate sizing and placement of RESs can improve the network efficiencies and performances in terms of voltage profile, reduce power losses and mitigate reverse power flow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global concerns about electricity and its impact on the environment have spurred the integration of RESs and the creation of creative, useful microgrid (MG) solutions1,2. Moreover, the development of the electrical energy industry today depends on the increasing use of renewable biomass3. These small-scale autonomous power systems encompass a mix of conventional and RESs, energy storage systems (ESSs), and electronic power converters. Additionally, numerous researchers have focused on renewable-based industrial applications, such as charging stations, utilizing various sources including solar, wind, hydrogen, and biomass4,5. MGs can operate independently or in conjunction with a utility grid6,7,8,9. RESs transform these natural occurrences into energy that may be used. These systems mostly produce electricity, but they can also heat chemicals or produce mechanical energy. All of these energy sources are essential in the fight against greenhouse gas emissions and climate change because of their low pollution levels10. The electrical grid is made up of loads, power plants, and power wires with various voltage levels. Depending on the voltage levels, these components can be utilized to construct various electrical network topologies.

Furthermore, to maintain general stability, an electrical grid needs to dynamically regulate the entire production-to-consumption cycle. Several renewable energy production techniques can be connected into the electrical grids. These include combined heat plants, wind turbines, solar panels, and power plants. The integration of a large quantity can lead to issues such as regulation, protection, energy quality, and voltage control. Therefore, innovative solutions to these problems are crucial11. To improve the hosting capacity of renewable systems in low-voltage distribution networks, research was presented a practical strategy founded on voltage control and dynamic voltage regulation12,13. This approach was utilized reactive power control along with two types of compensation: on-load tap-changing transformers and a reactive power controller with coordinated voltage management. Furthermore, a distributed generator optimal placement and sizing based on accelerated particle swarm optimization (APSO) was employed to reduce the network power loss rate14.

Electricity distribution networks possess distinct characteristics, including the following:

-

Radial or weakly meshed structures;

-

Operating with unbalanced loads and distributed loads;

-

High number of buses and branches;

-

Wide range of resistance and reactance values; and

-

Operating across multiple phases.

Distribution networks are the last link in the power supply system because they are in charge of supplying energy to final consumers. The effectiveness of the analysis carried out by these systems determines whether customers receive a stable and reliable power supply. The primary objective of power flow analysis is to ascertain the steady-state operational characteristics of a distribution network. The findings of voltage profiles, active and reactive power flows, and possible problems such as overloads and voltage violations are all part of this process15. Over the past 20 years, various solution techniques, including Newton–Raphson and rapid decoupled power flow approaches, have proven effective in addressing power flow difficulties in transmission power systems16,17. However, challenges arise when these algorithms are extensively applied to faulty or improperly initialized power systems. Other traditional methods based on the Gauss–Seidel approach have been suggested for power flow analysis purposes18,19. Unfortunately, these methods may lose their effectiveness when applied to complex and large power networks, despite their durability. Distribution networks characterized by their wide range of resistance and reactance values and radial structure fall into the category of ill-conditioned power systems for the standard Newton–Raphson, fast decoupled power flow and Gauss–Seidel methods. In fact, high resistance and reactance ratios characterize the distribution lines, which can be neglected in transmission power systems. Furthermore, considering the emergence of RESs further emphasizes the need for modifications and enhancements in power system analysis20.

To address distribution network challenges, adjustments to conventional load flow methods are imperative. Power flow methods are often categorized into two groups21,22. The first group comprises recursive solutions with power flow equations expressed such that recurring differentiation is avoided23. This characteristic makes these methodologies suitable for real-time applications and large-scale power systems. These strategies integrate the distribution network graph by reconfiguring the power flow equations to yield a recursive formula24,25,26,27,28. The second class involves iterative solutions based on linear approximations, utilizing Taylor’s series expansion of power flow equations in real and complex domains. Within the same context, the backward/forward sweep method has been shown to be effective and robust in solving the load flow problem for static distribution networks28. This method is based on Kirchhoff current and voltage laws instead of Jacobian matrices.

In recent years, the proliferation of distributed generation (DG) systems, heavily reliant on renewable energy, has gained significant attention because of rapid advancements in their development29,30. The incorporation of DG units at the distribution level offers numerous benefits, including reduced peak loads, heightened system security and reliability, enhanced voltage stability, grid reinforcement, lowered on-peak operating costs, and decreased network losses31,32.

Owing to the enormous potential of RESs, the Tunisian company of electricity and gas (STEG), the main entity responsible for electrification in Tunisia, has developed several strategies and plans to integrate these sources into the national network, particularly into the LV distribution levels. However, depending on their location and capacity, RESs may degrade system reliability and performance. This study presents an analysis of the impact of the integration of RESs with the technical parameters of the Sfax-North distribution network within the Tunisian power grid. To accomplish this, the load flow problem incorporating PV and wind sources is modelled, and then, the backward/forward sweep method is adopted for its solution. This method is selected because it offers a comprehensive solution based on a precise power flow solution, as outlined in33,34,35. Even for exceedingly large power flow loads, this approach consistently delivers accurate computations.

The daily evolution of the network parameters is investigated and assessed under various penetration rates of PV and wind, such as without RESs penetration and with PV and/or wind resources. Hence, on the basis of the simulation results and comparative study, necessary discussions and interpretations regarding the impact of integrating RESs on voltage levels, branch currents, active power flows, and reactive power flows in the studied system are drawn. The novelty of this paper lies in its comprehensive and real-world assessment of integrating RESs, specifically P and wind power, into a low-voltage radial distribution network within the actual Tunisian power grid—a case rarely explored in existing literature. The key innovative aspects include:

-

Real-world impact analysis This study uniquely focuses on the Tunisian grid’s specific operational characteristics, offering practical insights into the technical impacts of high-level RESs integration, which can serve as a reference for similar developing regions.

-

Advanced power flow methodology Utilizing the backward/forward sweep technique in MATLAB provides an accurate and robust approach for analyzing power flow, voltage profiles, current levels, active power losses, and reactive power losses in Sfax radial distribution network.

-

Extensive comparative simulations The paper conducts multi-scenario simulations (without RESs, PV-only, wind-only, and combined RESs), offering a detailed comparative analysis that highlights the strategic benefits of RESs placement in enhancing grid performance comparing to existing literatures.

-

Superior performance metrics The study reports a power loss reduction rate of 1.88% alongside an improvement in voltage stability through increased voltage support, outperforming previous research. This significant efficiency gain underscores the potential of RESs integration to optimize Sfax radial distribution network performance beyond what has been achieved in earlier studies.

-

Strategic insights for future grids The findings provide novel insights into how distributed RESs can enhance grid stability, reliability, and efficiency in real-world low-voltage networks, offering valuable guidance for policymakers, grid operators, and researchers in regions with similar energy infrastructures.

This study, therefore, offers novel insights into the benefits of distributed RESs in enhancing the efficiency and reliability of real low-voltage distribution networks, especially in regions with similar infrastructure.

System under study

STEG has installed different distribution networks overall in the country, where electricity is supplied through medium-voltage (MV) lines at 10 kV, 15 kV or 30 kV and LV lines at 230/400 V. The Sfax-North distribution network is a LV distribution system that is part of the Tunisia national power grid. This real radial network is adopted in this study as a case study. The network consists of 33 nodes and 32 branches, as shown in Fig. 136. The network data are illustrated in Table 1.

System under study

A radial distribution network is a popular architecture in power distribution systems in which feeders are connected in a radial pattern, with power flowing in a single direction from the source to the loads. When modelling a real radial distribution network, several parameters must be taken into account. Additionally, this analysis explores the modelling of a real radial distribution network from the Tunisian STEG, both with and without distributed generators (DGs).

Modelling of the radial distribution network without DGs

Modelling transmission lines, distribution transformers, and loads in a radial distribution network involves applying mathematical equations and principles of electrical engineering. The following is an overview of the modelling process for each used component.

Distribution line model

The most often used model is the π-model, which is a simplified depiction of a distribution or transmission line. The π-model divides the distribution line into two portions by using two series impedance elements (Z) joined by a shunt admittance element (Y). Thus, the equivalent circuit of a distribution line can be described as shown in Fig. 237.

From the equivalent circuit illustrated in Fig. 2, the sending end voltage (Vs) and the sending end current (Is) can be represented in the following matrix form:

where Vr and Ir are the receiving voltage and current, respectively. Indeed, Avv, Avi, Aiv and Aii can be expressed as follows:

Note that the shunt admittance element (Y) represents the charging current of the distribution line due to its capacitance. However, it is often neglected for short distribution lines. This assumption is applicable for the distributed network examined in this study. Therefore, Eq. (1) becomes as follows:

Distribution transformer model

The equivalent π representation of a two-winding transformer in a radial distribution network is a simplified circuit model that represents the primary and secondary sides of the transformer via series and parallel elements. The equivalent π circuit diagram is illustrated in Fig. 338:

where Z denotes the transformer’s equivalent leakage reactance, and t represents the transformation ratio. In the equivalent π representation of a two-winding transformer in a radial distribution network, mathematical equations can be derived on the basis of the circuit elements.

Load model

The load model in a radial distribution network is often represented via a combination of real power (P) and reactive power (Q) components. Various load models can be used, depending on the level of detail required in the analysis. One common load model is the ZIP model, which considers three components: constant impedance (Z), constant current (I), and constant power loads. Figure 4 illustrates the circuit depiction of the ZIP model39.

The mathematical equations for the ZIP load model in a radial distribution network are as follows:

where P0 is the constant power component of the load and PZ is the constant impedance component of the load. Q0 represents the constant power component of the load. QZ is the constant impedance component of the load. V is the actual voltage magnitude at the load. V0 is the reference voltage magnitude.

These equations capture the relationships among the real power, reactive power, voltage magnitude, and constant impedance and power components of the load in a radial distribution network.

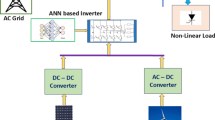

Modelling of the radial distribution network with DGs

Each DG unit in the radial distribution network needs to be modelled on the basis of its specific characteristics. This includes modelling power generation capabilities, such as solar PV or wind turbine models. The DG models should take into account various factors, including power output variability, voltage regulation capabilities, and responsiveness to network conditions.

PV array model

Solar cell modelling depends on the kind of diode configuration. The single-diode model is the most popular among the available diode models because of its simplicity and accuracy in many applications. Furthermore, in this study, we use a single-diode model to simulate a solar cell. Figure 5 displays a preliminary circuit diagram of the used PV array with \(N_{SS}\) series and \(N_{PP}\) shunt cell arrangements40.

The basic equation that describes the I–V characteristics of the PV array is given by the following equation:

where:

In these equations, the output current of the PV array can be represented by the following variables: Iph is the light-generated current produced by the solar cell. I0 is the reverse saturation current. VPV is the operating voltage of the PV array. ND is the diode ideality factor. Q is the electron charge. RSS is the series resistance. RPP is the panel shunt resistance. VTV represents the terminal voltage. VD represents the diode voltage. NCS is the series-connected cell quantity in a PV module. Figure 6 and Table 2 show the PV array’s electrical characteristics.

Wind turbine model

The mathematical equation for a wind model in a radial distribution network can be represented via a combination of power generation and control equations41. The power generated by a wind turbine depends on the wind speed and the turbine power curve. The following equation is commonly used to represent wind power generation:

where Pwind is the generated wind power. Ρ is the air density. A is the swept area of the turbine blades. Cp is the power coefficient, which represents the efficiency of the turbine. V is the wind speed. The values of ρ, A, and Cp are specific to the wind turbine being used and can be obtained from the manufacturer’s specifications or performance data.

Wind turbine control mechanisms are designed to adjust network voltage and frequency. These systems modify the power output in response to fluctuations in the grid. Depending on the grid characteristics and the control mechanism used, a wide range of control equations may apply. This is usually performed by controlling the turbine’s power factor. The turbine active power output may be adjusted to help stabilize the grid frequency via frequency regulation. The control mechanisms that can be utilized to do this include pitch control, active power control and all the characteristics is addressed in Fig. 7.

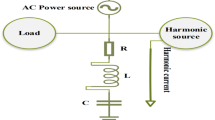

Power flow problem formulation

Electric grids are designed to accommodate power flows that transfer from the distribution network to the transmission network. Power injection can occur in the opposite direction, that is, from distribution to transmission, when DGs are injected into voltage levels other than the transmission network. In this case, bidirectional equipment is essential. Because LV distribution networks are usually oversized to handle increased consumption, there might not be any immediate problems with power transfer limitations. However, over time, as DGs penetration rates rise, the direction of power transit may change and possibly cause local congestion42. Figure 8 shows the power flow directions in an LV distributed network before and after the integration of DGs.

In this work, a load-balancing technique was developed that analyses the LV distribution network to identify the current directions and magnitudes flowing across the lines, as well as the nodal voltages. It is built on two topology-derived matrices: the bus injection branch current (BIBC) and the branch current bus voltage (BCBV) matrices. The procedure of this method is applied to a simple distribution network, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

The primary premise of this method is that, on the basis of network data, active power injections and the reactive and active power consumption at nodes are recognized to be known. Except for the balancing node voltage, which is equal to its nominal value, all node voltages are initially considered equal to unity.

Furthermore, the apparent power consumed by the loads is given by:

where Pi and Qi are the active and reactive powers of the load, respectively, and the voltages at nodes i and Ii* are the conjugates of the current injected into node i.

The current injection at iteration k is expressed as follows:

where \(\overline{V}^{k}_{i}\) \({\overline{\text{V}} }^{\text{k}}\text{i}\) is the voltage at node i at the kth iteration.

On the basis of Eq. (11), currents flowing into the lines can be calculated by starting at the end nodes and applying the current Kirchhoff law. These currents can then be expressed as functions of the various node currents as follows:

These relationships can subsequently be expressed in matrix form as follows:

where \(\left[ B \right] = \left[ {B_{1} B_{2} B_{3} B_{4} B_{5} } \right]\) is the vector of currents flowing through the network various lines, and \(\left[ I \right] = \left[ {I_{2} I_{3} I_{4} I_{5} I_{6} } \right]^{T}\) is the vector of currents injected at the network nodes.

Beginning at the source substation, where the voltage is assumed to be constant, we can calculate the voltage drop across each line using the following method:

where \(\overline{V}_{i}\) \(\overline{{\text{V} }_{\text{i}}}{\text{ and }\overline{\text{V}} }_{\text{j}}\) and \(\overline{{V_{j} }}\) are the complex voltages at nodes i and j, respectively. \(\overline{Z}_{ij} = R_{ij} + s*X_{ij}\) is the impedance of line (i, j). \(R_{ij}\) and \(X_{ij}\) are the resistance and reactance of the line, respectively.

By calculating the voltage drop in a line (i, j), the voltage at node j can be determined according to the following equation:

These voltage drops are expressed by the following system:

The system of equations provided in Eq. (16) can be represented in the following matrix form:

Then, Eq. (17) can be simplified as follows:

By combining Eqs. (13) and (18), \(\left[ {\Delta V} \right]\) can be expressed as follows:

where:

This process continues until the difference between the voltage profiles of two successive iterations falls below a predetermined threshold:

where \(\varepsilon\) is a prespecified value that represents the convergence threshold.

Figure 10 summarizes the principle of this method and the various steps to be followed to determine all nodal voltages. The method also calculates the active and reactive losses in the radial distribution network lines.

The active and reactive power losses in the distribution line can be expressed as follows:

The total active and reactive losses in the distribution network are given by:

where N denotes the total number of nodes.

According to the mathematical formulation of this technique used in this study, only one matrix is required for the power flow calculation, which is [DLF]. This matrix is calculated via Eq. (20). This means that the admittance matrix, which is used in conventional algorithms, is not required in this technique. As a result, this method is generally more efficient and accurate for distribution networks compared to traditional techniques. Additionally, its primary advantage lies in its ease of implementation and significantly reduced computation time.

Simulation results

The Sfax-North distribution network, a LV radial distribution system, is an integral component of the Tunisian national power grid (STEG). This actual radial distribution network serves as the focus of this study, acting as a representative case study. To assess the impact of RESs on the investigated Sfax radial distribution network, four different cases are considered:

-

(i)

Case 1: without RESs integration.

-

(ii)

Case 2: with a PV source only.

-

(iii)

Case 3: with a wind source only.

-

(iv)

Case 4: with both a PV and a wind sources.

The investigated load flow methodology, which is based on backward/forward sweep, is implemented within the MATLAB environment. Indeed, the simulation results are subsequently displayed and discussed. These results offer insights into the effects of incorporating RESs like PV and wind on various aspects such as voltage levels, branch currents, active power flows, reactive power flows, and power losses. This analysis enables a comprehensive understanding of the implications of integrating RESs into the studied network.

Case 1

In this case, the load flow problem has been successfully solved without the integration of RESs into the studied radial distribution network. It is to be underlined that the backward/forward sweep is utilized to solve the load flow problem. The simulation is conducted via the load demand curve depicted in Fig. 11.

Figure 12 shows the voltage levels at different nodes for two levels of demanded power (PD), which are 20 kW and 82 kW. As the PD rises from 20 to 82 kW, the voltages at most nodes tend to decrease. This reduction in voltage is likely due to the increased load on the system caused by higher power consumption. Increased electricity demand leads to higher current flows in the studied radial distribution network, causing significant voltage drops across distribution lines. In the studied network, nodes 27 and 28 experience voltage levels below the permissible 90% threshold, resulting in elevated power losses and reduced network efficiency. Indeed, this study focuses on mitigating these issues by implementing strategies to enhance voltage levels at critical nodes, thereby minimizing losses and improving overall system performance.

Figure 13 shows the branch currents of the studied radial distribution network, demonstrating that currents increase proportionally with higher PD levels to meet the rising load demands. This highlights the importance of designing robust networks to handle increased currents and maintain reliability under varying load conditions.

Figures 14 and 15 illustrate the active and reactive power flows through the various branches of the studied radial distribution network at two different levels of PD.

As PD increases in the radial distribution network, both active and reactive power flows rise across branches, consistent with fundamental electrical principles. Higher load demands require more active power, while reactive power flows increase proportionally from the system’s reactive components to support the rising demand.

Nodes 27 and 33 exhibit the lowest voltages and significant power losses in the studied network (see Fig. 16), as identified through a node voltage analysis using the backward/forward sweep load flow technique. These issues suggest potential voltage drops and inefficiencies within the investigated network. To address these challenges, integrating RESs, such as PV systems and wind power, is proposed. In this study, a PV source is placed at node 27, improving both voltage levels and power while reducing losses, with benefits extending to downstream nodes. Similarly, a wind power generator is installed at node 33, the final node, enhancing the voltage profile, minimizing power losses, and ensuring power continuity. These interventions effectively mitigate voltage drops and power losses, improving the overall efficiency and reliability of the real radial distribution network.

Case 2

In this case, where a PV source is connected to node 27, Fig. 17 depicts the relationship between the PD and the photovoltaic power production (Ppv). Figure 18 shows the voltages at different nodes for two operating conditions: (i) PD = 20 kW and Ppv = 0 kW and (ii) PD = 80 kW and Ppv = 102 kW. The integration of the PV generator into the studied network significantly enhances the voltage profile by reducing dips and improving stability. This effect is most pronounced during periods of excess energy generation and low demand, such as between 11:00 AM and 3:00 PM. By injecting surplus energy into the network, the PV source stabilizes voltage levels, especially in nearby nodes, and reduces reliance on traditional power sources, showcasing the critical role of photovoltaic source in optimizing grid performance and reliability.

During this period, the PV source produces more electricity than is needed, resulting in surplus energy being injected into the radial distribution network. This raises voltages, particularly near the PV connection point, reduces transmission losses, and mitigates voltage dips, significantly enhancing network stability and efficiency.

Figure 19 shows the currents in different branches for the two aforementioned operating conditions.

A comparison of these results with the scenario without a PV source reveals a clear shift in current distribution. As the PV produces energy, the total power flow from the principal source node to neighboring nodes decreases. On the other hand, the PV source power injection increases the power flow in branches near the PV connection point. This is because the PV system provides more current to the branches around it, resulting in higher currents in those branches.

The active power flows in various branches for the two previously indicated operating conditions are shown in Fig. 20. When the power generated by the PV source exceeds the local electricity demand, the power flow dynamics undergo significant changes. As observed in nodes 1–8 and 25–26, the active power becomes negative, indicating that the excess electricity is being fed back into the grid. This behavior highlights the bidirectional capabilities of grid-connected PV systems, where surplus power is injected into the grid. Consequently, the PV system not only meets local demand but also contributes to the broader power generation and distribution network. This enables the integration of clean and sustainable energy sources into the existing real distribution network.

Figure 21 illustrates the distribution of reactive power flows across different branches of the studied network.

The generation of the reactive power of PV generator is generally limited compared with their active power output. As a result, the impact of PV systems on reactive power flows in the network is usually insignificant. However, fluctuations in reactive power flows could result from enormous variations in PD. Even when some reactive power is produced by the PV system, it typically constitutes a small fraction of the total power generated. As a result, the integration of PV generator does not substantially affect the reactive power flows in the network branches, with their primary contribution being in the form of active power to meet local demand.

Case 3

In this case, a wind source is connected at node 33 of the studied radial distribution network. Figure 22 illustrates the evolution of the PD and wind power generation (Pwind) over a 24-h period.

Figure 23 shows the voltage levels at various nodes under two operating conditions: PD = 20 kW and Pwind = 19.93 kW at 4:00 AM, and PD = 80 kW and Pwind = 13.37 kW at 5:00 PM. The investigation shows that the PD amplitude has a considerable impact on the voltage levels throughout the studied network. Significant voltage drops at different nodes occur when the load demand is high, exposing the network’s susceptibility to high loading situations. This is explained by the wind turbine’s restricted capacity, which prevents it from exceeding the peak PD. As a result, especially during peak hours, the wind power supply is not enough to fulfill the growing demand. In order to preserve grid stability, this analysis highlights how crucial it is to strike a balance between load requirements and the incorporation of renewable energy.

Figure 24 shows the active power flows in different branches for the same operating conditions. Power flow can reverse when the PD equals the wind turbine’s generation, with excess energy returning to the network. The dynamic impact of wind turbine integration and the requirement for flexible grid infrastructure are shown by this two-way flow. Notably, branch 32 experiences the largest active power injection into the grid due to the integration of wind power at node 33.

The reactive power capability of the studied network is illustrated in Fig. 25. Moreover, the reactive power link is relevant only when power consumption increases. In this context, its stable reactance power output remains at a relatively constant level, thereby helping to maintain flow balance.

Case 4

In case four, a PV source is integrated at node 27, whereas a wind power source is integrated at node 33. Figure 26 illustrates the evolution of PD, PV production, and wind power production over a 24-h period. To study the performance of the Sfax-North distribution network when RESs are integrated, two different operating conditions are considered. Hence, the simulation results presented in Figs. 27, 28, 29 and 30 are based on the following operating conditions: (i) PD = 20 kW, Ppv = 0 kW, and Pwind = 19.93 kW at 4:00 AM, and (ii) PD = 80 kW, Ppv = 102 kW, and Pwind = 19.53 kW at 1:00 PM.

Figure 27 illustrates the voltage profiles of the studied network under various operating conditions. The analysis shows that integrating wind and PV energy enhances the voltage profile compared to the base scenario (Case 1). This improvement indicates that voltage levels are better regulated and remain below legal limits at various electrical network nodes. Moreover, a significant finding emerges when wind and PV power outputs increase due to favourable weather conditions, such as rising wind speeds and abundant sunlight. During a specific time (between 11 AM and 03 PM), the voltage magnitudes of the majority of nodes, particularly those near the PV and wind source connections, are greater than that of the source node essentially in nodes nearby to PV and wind sources connection. This phenomenon is most apparent in the nodes close to the PV and wind power source connections. In conclusion, these results demonstrate that integrating RESs, particularly with significant wind and PV power output, enhances the voltage profile and enables higher voltage levels across the electrical grid, improving overall stability and performance of the Sfax radial distribution network.

Figure 28 depicts the currents flowing through the network branches under the two aforementioned conditions. A comparison of the results with the case without RESs reveals an interesting observation: currents at nodes near the main source decrease, while currents at nodes close to the wind and PV connection points increase. This decline in current magnitude at nodes near the main source can be attributed to some of the power demand being met by RESs, resulting in an overall decrease in current flow from the main source node. This shift highlights the effectiveness of RESs integration in the Sfax radial distribution network in meeting local power demands, thereby reducing the load on the main source and enhancing overall network efficiency.

The active power flows in the Sfax radial distribution network branches are presented in Fig. 29. Referring to Fig. 29, it can be seen that when the combined power generated by the PV and wind sources exceeds the PD, there is a significant change in the power flow direction. PV and Wind sources export electricity to the electrical grid when their output exceeds local demand, with surplus power from RESs flowing through branches 1–8, 10–12, 25–26, and 32. This capability to inject excess power into the electrical grid highlights a crucial advantage of RESs integration in the Sfax radial distribution network, enhancing energy utilization and grid efficiency.

Figure 30 shows the reactive power flows in the Sfax radial distribution branches for both operating conditions. Typically, PV and wind sources generate relatively low and constant levels of reactive power. As a result, their influence on the reactive power flows upon the integration of RESs is generally minimal. However, as power demand increases, fluctuations in reactive power flows may become evident. These variations occur because a higher power demand alters the reactive power exchange within the studied network.

Figure 31 highlights the active power losses of the Sfax radial distribution network for cases with and without the integration of RESs. The figure clearly demonstrates the notable benefit of RESs integration, which is the reduction in active losses. The maximum active power loss without the RESs integration is approximately 7366.71 W. While, when RESs are integrated in the studied network, the maximum active power loss decreases to around 4251.66 W. This indicates that the integration of PV and wind energy sources results in a reduction of active power loss by about 50%.

Table 3 analyzes the active power loss rate (∆APL) across scenarios without and with RESs integration. The integration of high PV and wind power sources in the Sfax radial distribution network dramatically reduces ∆APL. This reduction indicates the good influence of RESs on decreasing power losses, notably during periods of higher renewable production, such as at 09:00 AM, when ∆APL exceeds 3990.5 W compared to 988.7 W at 05:00 PM. As a result, integrating PV and wind sources improves not only energy efficiency but also network operating performance by significantly reducing active power losses.

Table 4 compares the voltage (∆V) at critical nodes of the Sfax radial distribution network with and without RESs integration. The results show that ∆V increases dramatically, especially in nodes near the RESs connecting sites. When PV and wind power sources are combined, the voltage rises significantly, reaching 132 V at Node 27 with Ppv = 102 kW and Pwind = 19.53 kW. This rise can be described to the direct injection of active electricity from renewable energy sources, which decreases reliance on the main grid and minimizes voltage drops along distribution lines. As a result, the significant penetration of RESs improves voltage stability, decreases losses, and overall performance of the Sfax radial distribution network.

Table 5 represents a comparative analysis of active power loss rate in radial distribution networks with integrated RESs. Referring to this table, one can underlined that the rate of power loss resulting from the integration of the RESs is equivalent to 2.98% of the total power transferred over the low-voltage radial distribution network. This reduction in losses serves as evidence of the improved quality and efficiency of the network resulting from the integration of PV and wind energy sources comparing to other existing works. Indeed, the combined maximum power capacity of approximately 122 kW from the PV and wind turbine energy sources reflects a high integration rate of RESs into the studied electrical grid. This substantial renewable energy contribution significantly improves the efficiency and reliability of the Sfax radial distribution network, reducing dependency on conventional power sources and enhancing overall grid performance.

Conclusions

This study presents an overview of the impact of integrating PV and wind sources on the electrical parameters of a real LV radial distribution network. The Sfax-North distribution network within the Tunisian grid is taken as a test network. To identify the optimal placement of the RESs, the load flow problem for the studied network comprising 33 nodes and 32 branches is solved via a backward/forward sweep-based technique. Then, nodes with low voltages are selected as the best location for the RESs.

To provide a more effective investigation of the impact of RESs on the studied network, a modified model for the power flow problem incorporating PV and wind sources is developed where four cases are considered:

-

Without RESs;

-

The PV source is integrated at node 27;

-

The wind source is integrated at node 33.

-

The PV source is integrated at node 27, and the wind source is integrated at node 33.

The simulation results conducted in the MATLAB environment reveal that the RESs optimal placement can leverage their decentralized characteristics to achieve substantial improvements in the studied network voltage profile. Additionally, this strategic integration leads to a notable reduction in power losses across the distribution network. These findings underscore the potential benefits of incorporating RESs into electrical grids, highlighting their role in enhancing overall system performance and efficiency. Indeed, the RESs integration significantly enhances the performance and efficiency of the analysed Sfax-North LV radial distribution network, resulting in a remarkably low power loss rate of 2.98%. This performance surpasses that reported in other existing studies, highlighting the advantages of RES integration in optimizing network efficiency.

However, the obtained results show that high penetration of RESs can result in reverse power flow. The proposed research could be expanded to explore the integration of energy storage systems and voltage regulators with distributed generation. This approach aims to enhance the management and control of bidirectional power flows within the studied network.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- LV:

-

Low voltage

- RESs:

-

Renewable energy sources

- MGs:

-

Microgrids

- DG:

-

Distributed generation

- STEG:

-

Tunisian company of electricity and gas

- BIBC:

-

Bus injection branch current

- BCBV:

-

Branch current bus voltage

- PD:

-

Demanded power

- Ppv:

-

PV power

- Pwind:

-

Wind power

References

Renewable Energy—Powering a Safer Future United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/raisingambition/renewable-energy (Accessed 15 Dec 2022).

Alvarez-Diazcomas, A., Estévez-Bén, A. A., Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J., Martínez-Prado, M. A. & Mendiola-Santíbañez, J. D. A novel RC-based architecture for cell equalization in electric vehicles. Energies 13, 2349 (2020).

Mendoza-Varela, I. A., Alvarez-Diazcomas, A., Rodriguez-Resendiz, J. & Martinez-Prado, M. A. Modeling and control of a phase-shifted full-bridge converter for a LiFePO4 battery charger. Electronics 10, 2568 (2021).

Kumar, A., Kumar, M., Soomro, A.-M. & Kumar, L. Techno-economic optimization of novel stand-alone renewable based electric vehicle charging station near Bahria Town Karachi, Sindh Pakistan. Energy Eng. 121, 1439–1457 (2024).

Kumar, K., Soomro, A. M., Kumar, M., Kumar, L. & Arici, M. Sustainable on-grid solar photovoltaic feasibility assessment for industrial load. J. Central South Univ. 30, 3575–3585 (2023).

Alvarez-Diazcomas, A. et al. A review of battery equalizer circuits for electric vehicle applications. Energies 13, 5688 (2020).

Alvarez-Diazcomas, A., Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J. & Carrillo-Serrano, R. V. An improved battery equalizer with reduced number of components applied to electric vehicles. Batteries 9, 65 (2023).

Benefits of Electric Cars on Environment |EV & Petrol Cars | EDF. Available online: https://www.edfenergy.com/ (Accessed on 15 December 2022).

Johansson, B. Security aspects of future renewable energy systems—a short overview. Energy 61, 598–605 (2013).

Zdiri, M. A. et al. Design and analysis of sliding-mode artificial neural network control strategy for hybrid PV-battery-supercapacitor system. Energies 15, 4099 (2022).

Jha, K. & Shaik, A. G. A comprehensive review of power quality mitigation in the scenario of solar PV integration into utility grid. e-Prime-Adv. Electric. Eng. Electron. Energy, 100103 (2023).

Khan, M., Kumar, M., Soomro, A. M., & Shoukat, A.: Enhancing the photovoltaic hosting capacity in low voltage distribution. In 2022 Third International Conference on Latest trends in Electrical Engineering and Computing Technologies (INTELLECT), pp. 1–6 (2022).

Leghari, Z. H. et al. Effective utilization of distributed power sources under power mismatch conditions in islanded distribution networks. Energies 16, 2659 (2023).

Mahesh, K., Nallagownden, P. A. L. & Elamvazuthi, I. A. L. Optimal placement and sizing of dg in distribution system using accelerated PSO for power loss minimization. In 2015 IEEE Conference on Energy Conversion (Cencon), IEEE, pp 193–198, 2015.

Adhikari, A. et al. Stochastic optimal power flow analysis of power system with renewable energy sources using adaptive lightning attachment procedure optimizer. Int. J. Electric. Power Energy Syst. 153, 109314 (2023).

Sereeter, B., Vuik, C. & Witteveen, C. On a comparison of Newton-Raphson solvers for power flow problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 360, 157–169 (2019).

Eltamaly, A. M., Sayed, Y., El-Sayed, A. H. M. & Elghaffar, A. N. A. Optimum power flow analysis by Newton raphson method, a case study. Ann. Fac. Eng. Hunedoara 16(4), 51–58 (2018).

Chatterjee, S. & Mandal, S. A novel comparison of Gauss-Seidel and Newton-Raphson methods for load flow analysis. In 2017 International Conference on Power and Embedded Drive Control (ICPEDC) 2017, pp 1–7, IEEE.

Putri S. M., Maizana D., & Bahri, Z. (2021) Analysis of smart grid power flow system with Gauss‒Seidel method. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 753, 1, p. 012005 (2021).

Constante-Flores, G. E. & Illindala, M. S. Data-driven probabilistic power flow analysis for a distribution system with renewable energy sources using Monte Carlo simulation. IEEE Trans. Industry Appl. 55(1), 174–181 (2018).

Skolfield, J. K. & Escobedo, A. R. Operations research in optimal power flow: A guide to recent and emerging meth-odologies and applications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 300(2), 387–404 (2022).

Guo, Y., Baker, K., DallAnese, E., Hu, Z. & Summers, T. H. Data-based distributionally robust stochastic optimal power flow—Part I: methodologies. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 34(2), 1483–1492 (2018).

Overbye, T. J.; Hutchins, T. R.; Shetye, K.; Weber, J.; & Dahman, S. (2012) Integration of geomagnetic disturbance modeling into the power flow: A methodology for large-scale system studies. In 2012 North American Power Symposium (Naps), pp. 1–7. IEEE.

Montoya, O. D., Zishan, F. & Giral-Ramírez, D. A. Recursive convex model for optimal power flow solution in monopolar DC networks. Mathematics 10(19), 3649 (2022).

Montoya, O. D., Grisales-Noreña, L. F. & Hernández, J. C. A recursive conic approximation for solving the optimal power flow problem in bipolar direct current grids. Energies 16(4), 1729 (2023).

Rao, S., Feng, Y., Tylavsky, D. J. & Subramanian, M. K. The holomorphic embedding method applied to the power-flow problem. IEEE Trans. Power Syst/. 31(5), 3816–3828 (2015).

Yang Y., & Wei, H. Recursive reduced-order and decoupling algorithm for solving transient stability constraints opti-mal power flow. In 2014 International Conference on Power System Technology, pp. 170–175. IEEE (2014).

Dukpa, A., Venkatesh, B. & El-Hawary, M. Application of continuation power flow method in radial distribution sys-tems. Electric Power Syst. Res. 79(11), 1503–1510 (2009).

Mehigan, L., Deane, J. P., Gallachóir, B. Ó. & Bertsch, V. A review of the role of distributed generation (DG) in future electricity systems. Energy 163, 822–836 (2018).

Theo, W. L., Lim, J. S., Ho, W. S., Hashim, H. & Lee, C. T. Review of distributed generation (DG) system planning and optimisation techniques: Comparison of numerical and mathematical modelling methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 67, 531–573 (2017).

Kandasamy, M. et al. Strategic incorporation of DSTATCOM and distributed generations in balanced and unbalanced radial power distribution net-works considering time varying loads. Energy Rep. 9, 4345–4359 (2023).

Jooshaki, M. et al. On the explicit formulation of reliability assessment of distribution systems with unknown network topology: Incorporation of DG, switching interruptions, and customer-interruption quantification. Appl. Energy 324, 119655 (2022).

Alvarez-Bustos, A., Kazemtabrizi, B., Shahbazi, M. & Acha-Daza, E. Universal branch model for the solution of op-timal power flows in hybrid AC/DC grids. Int. J. Electric. Power Energy Syst. 126, 106543 (2021).

Nassar, M. E. & Salama, M. M. A. A novel branch-based power flow algorithm for islanded AC microgrids. Electric Power Syst. Res. 146, 51–62 (2017).

Farivar, M. & Low, S. H. Branch flow model: Relaxations and convexification—Part I. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 28(3), 2554–2564 (2013).

Souifi, H. et al. Impacts of PV penetration into LV Distribution Network: Case study for Southeast Region of Tunisia, Sfax. In 2018 7th International Conference on Systems and Control (ICSC), pp. 251–257. IEEE (2018).

Robles Balestero, J. P., Leon Colqui, J. S. & Kurokawa, S. Using the exact equivalent π-circuit model for representing three-phase transmission lines directly in the time domain. Energies 16(20), 7192 (2023).

Cano, J. M., Mojumdar, M. R. R., Norniella, J. G. & Orcajo, G. A. Phase shifting transformer model for direct approach power flow studies. Int. J. Electric. Power Energy Syst. 91, 71–79 (2017).

Asres, M. W., Girmay, A. A., Camarda, C. & Tesfamariam, G. T. Non-intrusive load composition estimation from ag-gregate ZIP load models using machine learning. Int. J. Electric. Power Energy Syst. 105, 191–200 (2019).

Dhouib, B., Zdiri, M. A., Alaas, Z. & Hadj Abdallah, H. Fault analysis of a small PV/wind farm hybrid system connected to the grid. Appl. Sci. 13(3), 1743 (2023).

Basbas, H., Liu, Y. C., Laghrouche, S., Hilairet, M. & Plestan, F. Review on floating offshore wind turbine models for nonlinear control design. Energies 15(15), 5477 (2022).

Chandran, C. V., Basu, M., Sunderland, K., Pukhrem, S. & Catalão, J. P. Application of demand response to improve voltage regulation with high DG penetration. Electric Power Syst. Res. 189, 106722 (2020).

Zdiri, M. A., Dhouib, B., Alaas, Z. & Abdallah, H. H. Optimizing solar PV placement for enhanced integration in radial distribution networks using deep learning techniques. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 14(2), 13681–13687 (2024).

Zdiri, M. A., Dhouib, B., Alaas, Z., Salem, F. B. & Abdallah, H. H. Load flow analysis and the impact of a solar PV generator in a radial distribution network. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res 13(1), 10078–10085 (2023).

Prakash, P., Meena, D. C., Malik, H., Alotaibi, M. A. & Khan, I. A. A novel analytical approach for optimal integration of renewable energy sources in distribution systems. Energies 15(4), 1341 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.Z.; B.D.; B.K.; J.M.G. and H.H.A wrote the main manuscript text. M.A.Z.; B.D. prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interest of any author in any form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zdiri, M.A., Dhouib, B., Khan, B. et al. Impact assessment of photovoltaic and wind energy integration on low voltage distribution networks in Tunisia. Sci Rep 15, 10594 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93488-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93488-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Photovoltaic power generation at the faculty of economic sciences and management of Sfax, Tunisia

Discover Sustainability (2025)