Abstract

In order to explore the mechanism of rockburst in tunnels constructed by drilling and blasting method in high ground stress strata, this study reformed the physical model test system of rockburst in deep tunnels and the high-pressure gas explosion excavation system, and successfully reproduced the process of rockburst disaster in drilling and blasting construction. Based on the existing research results and preliminary tests, a composite material with similar brittleness and rock burst tendency index to the granite on site was developed, and a cubic rock burst model of 500 × 500 × 500 mm3 was poured. The test results show that in the gas explosion excavation, the air pressure impact causes the test block to be destroyed instantaneously, the small fragments splash and the explosion sound is significant, indicating that the instantaneous release of gas can cause material damage and simulate the dynamic characteristics of the blasting process. From a macro point of view, rockburst originates from the stress adjustment of surrounding rock of the cavern and the energy transfer and dissipation process inside the rock mass. The residual energy is released in the form of dynamic energy and dissipated by dynamic mechanism. Microscopically, the material is compressed and destroyed in a small range of gas explosion tube pores, and the surrounding rock debris is mainly tensile and shear failures. The shear and tensile stress make the tunnel damage debris complex. The test results show that the stress at the measuring point 3 cm away from the cavern after excavation drops sharply at T = 11915s, with a decrease of 56.69%. At 30.50 cm from the cavern, the strain at the measuring point 3 cm from the cavern increases. The sharp rise of acoustic emission count and energy indicates that the rock burst phenomenon is sudden. The test method of this study effectively simulates the rock burst of tunnel constructed by high ground stress drilling and blasting method, which provides important experimental basis and data support for theoretical research and engineering practice of rock burst.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rockburst is a dynamic phenomenon wherein the accumulated elastic deformation of underground rock mass is abruptly released due to underground engineering excavation or external disturbance, leading to the bursting and ejection of surrounding rock. It mainly occurs in the deep sections of underground mining or areas with a high concentration of tectonic stress. Manifesting as a sudden failure phenomenon, it poses a significant threat to the safety of engineering construction. With the continuous development of underground resources and the expansion of underground infrastructure into greater depths, the severity of rockburst disasters is becoming increasingly prominent. The breeding environment and conditions of rockburst are highly complex, and the reasons for its formation are diverse.

The initiation mechanisms of rockburst are highly complex and multifaceted. Researchers globally have extensively investigated its formation and evolution through experimental, numerical, and theoretical approaches, including experiments, simulations, and theories, to study the formation and evolution of rockburst and its influencing factors1,2,3,4,5. In the research on similar materials, Zhou6 implemented a total of 25 groups of proportioning schemes in accordance with the principle of orthogonal design. By setting the mass ratio and water content of quartz sand, barite powder, gypsum, and cement, the influence of the properties of rockburst model materials on test results and the impact of the strength and brittleness of the model materials on the rockburst tendency were examined. Jia7 utilized the orthogonal experimental design method to match the similar materials of white sandstone and selected quartz sand content, iron powder content, gypsum - cement ratio, and sand particle size as the influencing factors. Based on elastic energy index, brittleness index, and residual elastic energy index parameters, the mechanical properties of white sandstone were simulated. Hou8 employed the orthogonal test principle to deeply explore the influence of gypsum - cement ratio, sand mixing rate, water mixing rate, and borax content on the mechanical properties of deep dolomite similar materials. Zang9 introduced the dimensional - analysis method of the rock - burst energy principle to formulate a material that complies with the failure characteristics of deep hard rock. Lin10 utilized gypsum as the similar material for the rock - burst test, conducted a gradient - loading test, and analyzed the microscopic damage. From the foregoing research, it can be discerned that gypsum and cement are currently the primary materials for rock - burst - similar materials. These materials possess good plasticity and are prone to inducing rock - burst - like phenomena.

In the aspect of model test research, He11,12,13 designed and developed the impact rockburst test system and conducted the impact rockburst test. Rockburst caused by acoustic vibrations resulting from mining and ex-plosive excavation and vibrations caused by support surface ruptures were observed. Si14 selected a 100 mm×100 mm×100 mm granite cube for in-depth study and applied three - dimensional unequal pressure conditions on this basis. The results indicate that the process of granite rockburst can be divided into four stages: resting period, particle ejection, rock falling off, and explosion. Shu15 studied the deformation and failure characteristics of tunnel surrounding rock under different horizontal stress conditions by using the model test method based on 3D printing technology. The findings show that when the lateral pressure coefficient is less than 1.4, the influence of layered soft rock on the deformation of surrounding rock is more significant. When the lateral pressure coefficient is greater than 1.4, with the increase of horizontal stress, the distribution of strain field exhibits uneven characteristics. Li16 discussed the complex mechanism of strain - type rockburst induced by deep underground excavation unloading, adopted the similar model test method, and successfully simulated and reproduced the occurrence process of strain - type rockburst disaster based on the setting of elastic loading boundary.

In the study of rockburst mechanism, Stacey17 analyzed the failure mechanism and mode of rockburst in high stress tunnels and divided rockburst into five categories: strain rockburst, buckling rockburst, pillar rockburst, shear rockburst, and fault slip rockburst. Kaiser and Cai18 further combined the types of rockburst into three categories: strain rockburst, pillar rockburst, and fault slip rockburst. After in-depth research, Qian19 pointed out that both pillar - type rockburst and strain - type rockburst display the phenomenon of volumetric instability of rock, so they should be classified into the same category. Based on this view, rockburst can be divided into two categories: strain rockburst and fracture - slip rockburst. Regarding the inoculation mechanism of strain - type rockburst, scholars at home and abroad have put forward strength theory, energy theory, stiffness theory, rockburst tendency theory, and nonlinear theory20,21,22,23,24. The strength theory25 posits that when the ratio of the stress of the surrounding rock to the strength of the rock mass (i.e., the strength - stress ratio) reaches a certain level (generally determined by tests), rockburst will occur.

The research on the mechanism of rock burst in tunnels is closely associated with the stability and key mechanical properties of actual tunnels. Guo26 Through three-dimensional finite difference analysis, the reasonable minimum overburden depth can be determined. The stress and displacement of the tunnel lining at the tunnel vault and the tunnel floor are analyzed. Moreover, a combination of the conventional method and numerical simulation analysis is put forward to predict the minimum overburden depth of the underwater shield tunnel. Wang27 proposed a simplified analytical solution for the longitudinal tunnel settlement induced by the axial load of a single pile and pile groups, and applied it to the preliminary estimation of tunnel settlement. Chen28 based on the Monte-Carlo stochastic analysis simulation method, the mechanical behaviors of the pile-soil-tunnel interaction during excavation in the vicinity of the tunnel are analyzed. The reliability evaluation method, which monitors the variation of relevant indexes, provides an effective approach for ensuring the stability of shield tunnel construction.By means of the analytical solution of the seepage field, Zhu29 utilized a numerical simulation model to analyze the hydraulic and ground responses caused by leakage in the double tunnel system.

It can be seen that although scholars at home and abroad have conducted extensive research on rockburst problems, more and more scholars have focused on studying the mechanism of rockburst through rockburst model tests. However, most of these studies are on preset holes or TBM tunneling. TBM construction under a high ground stress environment faces many challenges. Under such an environment, the hardness and strength of the rock in-crease, resulting in large consumption of TBM cutters, serious abnormal damage, large equipment vibration, and slow tunneling speed. The excavation method and its impact on the cavern are quite different from the drill and blast method. DBM can adapt to various geological conditions, with short preparation time and small equipment in-vestment, but there are few experiments and theoretical discussions5,30,31.

Determination of similar materials of tunnel surrounding rock

Engineering background

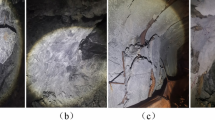

This test is grounded on the engineering geological conditions of the Duoji tunnel. The tunnel has a buried depth of 1150 m, with a curved wall arch section. Its maximum height is 10.60 m and the maximum width is 9.99 m. The tunnel is constructed using the full-section drilling and blasting method. After blasting excavation, there is a tendency of easy cracking and detachment on the left and right vaults within 10 m behind the tunnel face within 2 h. After blasting excavation, there is a tendency of easy cracking and detachment on the left and right vaults within 10 m behind the tunnel face within 2 h. For instance, a medium-intensity rockburst occurred on February 20, characterized by a single crater with a radial depth of 0.1–0.2 m and cumulative damage extending 0.6–0.7 m, the axis damage length was 1.5 m, the width was 0.8–1.3 m, the thickness was 6–12 cm, the block diameter was 11–16 cm, the blasting volume was 1.1 m³, and the rock burst grade was medium rock burst, as shown in Fig. 1.

Similarity theory

Physical model test is a physical simulation approach for studying engineering issues on a certain scale in accordance with the similarity principle. By means of the test to simulate the engineering process, the deformation and failure characteristics of the rock medium can be obtained more precisely, and the temporal and spatial relationship between the geological structure and the engineering structure can be mirrored. In the simulation of deep underground engineering, the weight of the model itself is considerably less than the boundary load. Consequently, in the development of similar materials for deep hard rock, the density ratio of the model material to the original rock, and the free selection of stress and geometric similarity constants can be disregarded. It is still necessary to consider the constraints of the nature and similarity relationship between the rock similar material and the original rock32,33,34. Excluding the consideration of the material weight, the main similarity constants of the physical model are:

Where, \({C_l}\)denotes the geometric similarity constant, p denotes the prototype, m denotes the model, the same below.

Where, \({C_\sigma }\)represents the stress similarity constant, \({C_E}\) represents the elastic modulus similarity constant, \({C_\varepsilon }\)represents the strain similarity constant, and \({C_\mu }\)represents the Poisson ‘s ratio similarity constant.

The similarity constant must satisfy the condition that the stress-strain curve in the prototype and the model is the same equation, so there are:

In accordance with the single-value condition in the formula (2), the similarity relation can be obtained as follows:

\(\varepsilon\)is a dimensionless variable, so \({C_\varepsilon }=1\). According to Eq. (4), the similarity relation to be satisfied is:

Determination of similar materials

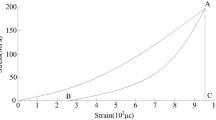

The mineral composition, Young’s modulus, tensile strength, compressive strength, and internal friction angle of the rock all exert an influence on the brittleness of the rock5. A series of mechanical property tests were performed on the granite within the surrounding rock of the tunnel in the rockburst Sects6,7,8,9,10. The stress-strain curves of the granite are presented in Fig. 2(a) and (b). Based on the previous research findings and the results of the pre-test, this experiment chose 42.5 cement and ɑ-high-strength gypsum as cementitious materials, 40–80 mesh quartz sand as aggregate, 600 mesh barite powder as a weight gain agent, and mixed it with an aqueous solution. The specific material is illustrated in Fig. 3. The ratio of the test material is: different proportions of the cement and high-strength gypsum combination, with barite powder (barium sulfate) accounting for 10%, quartz sand accounting for 20%, water accounting for 13% (the content of water is the percentage of the total mass of solid particles), while adding an appropriate amount of polycarboxylate superplasticizer, defoamer, and retarder to enhance material performance. After the specimen is fabricated, it is cured and dried at room temperature. The stress-strain curves of various similar ratio materials are depicted in Fig. 2(c) and (d).

As can be seen from Table 1, from the analysis of compressive strength, tensile strength and modulus of elasticity, the three ratios are close to each other and the relative error is small. According to the similarity theory, the similarity constants of stress and modulus of elasticity should be consistent, but it is difficult to achieve the same values in most of the actual model tests. In this test, the three values of the model materials are close to each other, and the stress similarity constants are in the range of 2.89–3.76. Owing to variations in mineral composition and geological heterogeneity, achieving consistency between the model material and the in situ rock in terms of brittleness and rockburst propensity remains challenging. Therefore, it is also necessary to evaluate the brittleness index and rockburst propensity index under different gradations.

Brittleness index evaluation index6 : Quantitative analysis of the relative size and rate of rock stress-strain post-peak curve decline.

Where: \({B_d}\) is brittleness index ; \({\sigma _c}\) is the peak strength ; \({\sigma _r}\) is the residual strength ; \({k_{a(AC)}}\) is the connection slope from the initial yield point to the starting point of the residual strength. The greater the \({B_d}\) value, the greater the brittleness of the rock.

Evaluation index of rockburst proneness35 : According to the uniaxial loading and unloading test, the rock is first loaded to 80% ~ 90% of its peak stress, and then unloaded to 5% of the peak stress. The ratio of elastic energy to dissipated energy in the rock loading and unloading cycle is the value of \({W_{et}}\).

Where: \({W_{et}}\) is the brittleness index of rock burst; \({E_R}\) is the elastic energy recovered during unloading; \({E_D}\) is the dissipated energy in the loading-unloading cycle.

According to Table 1 of the test results, the brittleness index is higher for the ratios of cement to gypsum of 0:1 and 1:4. The rock fracture index of 1:4 and 1:3 is also relatively high among the four ratios. In the uniaxial compression test, the rock blocks on the surface of the 1:4 and 1:3 specimens bulged out, peeled off and finally ejected. With the brittle sound of ‘bang’, the specimens cracked completely, and the residual strength after failure was almost zero, which was more in line with the instantaneous discovery of rock burst in practical engineering. Considering the above factors, the ratio of cement to high-strength gypsum as the model material is 1:4, which is more in line with the requirements and objectives of the composite rockburst model test. At the same time, the stress similarity constant obtained is 3.35.

Physical modelling test programme

Model test device and measuring point arrangement

This study is based on the deep tunnel rock burst physical model test system of Wuhan Institute of Geomechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. After innovative transformation, the system has the function of simulating the excavation of roadway drilling and blasting method, and its overall structure and functional details are shown in Fig. 4. The core of the test system consists of three parts: true triaxial rockburst loading system, gas explosion device excavation system, and data acquisition and detection device.

Among them, the true triaxial rockburst loading system harnesses hydraulic servo loading technology to accomplish precise loading and employs a computer to meticulously control the loading time as well as the data volume in the three directions of x, y, and z. During the loading process, the computer is capable of adjusting the loading forces in real time in accordance with the preset loading path, thereby ensuring the stability and accuracy of the loading operation.

As a crucial apparatus for simulating the excavation process of the actual tunnel drilling and blasting method, the gas explosion excavation system utilizes the gas explosion approach to mimic the effect of borehole explosions in practical projects. In the test, high-purity nitrogen was chosen as the gas source. Given that the initial pressure in the nitrogen bottle was merely 13 MPa, a pressurization system was incorporated to elevate the gas pressure to the requisite ideal value. During the test, the pressurized gas tank can release gas in 0.1 ~ 0.2s and transmit it to the gas explosion pipe through the gas distribution valve, thus simulating the excavation process of the tunnel drilling and blasting method.

In the loading process of the model test, the stress, strain and fracture characteristics of the sample were also comprehensively tested. Specifically, TDS dynamic strain acquisition instrument and FTB distributed optical fiber strain analyzer are used to collect dynamic data of micro pressure sensor box and strain sensing cable embedded in the test. At the same time, the acoustic emission detection system is used to monitor and record the fracture characteristic signal of the sample in real time.

The cubic test model measured 500 mm × 500 mm × 500 mm, with an excavation diameter of Φ100 mm and a depth of 500 mm.

The detection scheme encompasses a data acquisition system comprising stress and strain, acoustic emission, and other subsystems as depicted in Fig. 5. The internal pressure of the model is measured using a miniature pressure sensor. Two monitoring surfaces are established, and four sets of pressure sensors are positioned on each monitoring surface to monitor the pressure in four directions at 3 cm and 9 cm from the model wall. Strain measurement employs a grid strain sensing cable. Two monitoring surfaces are established, and four sets of strain sensing cables are positioned on each monitoring surface to monitor strain in four directions at 3 cm and 9 cm from the model wall. The layout plan of the stress and strain sensors empowers the monitoring system to effectively capture the mechanical response disparity between the stress concentration zone (3 cm) and the unloading zone (9 cm). Compared with conventional schemes, the spatial resolution of the data has been enhanced. Seven acoustic emission sensors are positioned on the surface of the specimen. The acoustic emission monitoring and acquisition system enables the elastic wave released when the sample is destroyed to be monitored in real time. These sensors are deployed to guarantee comprehensive surface coverage of the entire test block and minimize monitoring blind spots. The actual state of the cave wall is monitored via the camera, and the information of the cave wall is acquired in real time.

Excavation scheme

This experiment employed 12 gas explosion tubes. These gas explosion tubes were fabricated from high-strength alloys and possessed the characteristics of high temperature and high pressure to fulfill the test requirements. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the diameter of the gas explosion tube is 6 mm, which is divided into the inflatable tube and the gas explosion section. The length of the gas explosion section is 240 mm, featuring tiny holes. The high-pressure gas generates a substantial impact energy through these tiny holes within a very short time, thereby destroying the test block.

In order to fully simulate the intact state of the rock mass prior to excavation, a cylindrical test block of Φ100 mm×500 mm was fabricated using the same ratio of material as the model test specimen. When the cylindrical test block was cast, the gas explosion tube was reserved inside the test block. Since the excavation is accomplished in two times, the layout of the gas explosion tube is arranged in a front-and-back cross arrangement. Figure 7 shows the layout of the gas explosion tube. In this approach, all the gas explosion tubes are connected prior to excavation to avoid secondary connection during excavation. A damping foam plate with a thickness of 20 mm is placed in the center of the test block to preclude the influence of the first excavation on the second excavation.

Sample pouring

The sample casting process is depicted in Fig. 8. After the slender hexagonal sample is prepared and solidified, the strain gauge is affixed and placed in the mold according to the designed component position, and then poured together. Owing to the large size of the model specimen, it is challenging to cast it completely in one go. Hence, this test adopts the multi-layer casting approach. Simultaneously, the vibrating rod is utilized to stir the mould to reduce the pores and bubbles in the specimen, thereby minimizing the test error. The specimen was held for approximately 10 h. After reaching the initial setting strength, the metal tube was removed. When the specimen was completely solidified, it was demoulded and the prefabricated gas explosion tube was poured into the reserved hole in the centre. The specimens were placed in a ventilated location for maintenance, and the humidity and temperature were maintained during the maintenance to prevent the specimens from cracking. After 28 days of maintenance, the specimens meet the test conditions. When the cylindrical test block and the hexagonal sample are joined together on the basis of consolidation, it is essential to utilize similar materials to fill the pores between them. This facilitates the close fitting of the test block and cements them into a single entity, thereby creating a complete overall structure.

Stress loading path

To investigate the general law of rock fractures in tunnelling by drilling and blasting, based on the original stress field of the tunnel surrounding rock, the boundary load of the physical model is applied to the physical model testing machine for rock fractures in deep tunnels. Synchronous gradient loading is employed in this test, as illustrated in Fig. 9. The specific loading scheme is as follows:

-

(1)

Simultaneously, the loading was initiated at a rate of 0.8KN/s to 4 MPa, and the pressure was stabilized for 5 min. The variations in pressure and strain within the model were monitored in real time during the loading process.

-

(2)

After step (1), the pressure was simultaneously loaded to 20 MPa and the pressure was stabilized for 5 min.

-

(3)

Excavation of the tunnel on the model, using the high-pressure gas explosion device to excavate the first section, the pressure is stabilized for 15 min and the second section is excavated. The variations in pressure and strain within the model are monitored in real time during the excavation process.

-

(4)

The initial loading condition was maintained for 10 min after excavation and the variations in pressure and strain within the model were monitored in real time.

-

(5)

The load is increased until a strong rock burst occurs on the tunnel wall. Finally, the test apparatus is disassembled to observe the deformation and failure of the model.

Analysis of test failure characteristics

Characteristics of gas explosion excavation

During the test, the test phenomenon during gas explosion excavation was recorded using a high-speed camera. During excavation, the pressurized gas tank releases the gas within 0.1–0.2 s, and the gas is transmitted to the gas explosion tube via the gas distribution valve to simulate the blasting process. In this process, due to the gas impact, the test block is destroyed instantaneously. Upon failure, the test block exhibited brittle fragmentation, with fine particles (diameter < 5 cm) ejected radially from the excavation zone. As shown in Fig. 10, a large number of small fragments are spattered outside the hole, accompanied by a huge gas explosion. It indicates that at this time, within the range of gas explosion blasting, the gas instantaneously releases energy and destroys the test block instantaneously.

Characteristics of model failure mode

As depicted in Fig. 11, following the test, the gas explosion tube embedded within the similar material is entirely enveloped by the material. This makes it arduous to extract and reuse the tube. After the completion of the gas explosion excavation, the damage of the prefabricated test block is presented in Fig. 12, which reveals that the test block has been completely destroyed, and there are relatively fewer small fragments, mainly along the gas explosion pipe throughout the overall damage. It is primarily attributable to the high pressure engendered at the instant of gas explosion under the influence of gas explosion impact pressure. This high pressure acts upon the material surrounding the pores. Within the minute range of the pores, the material endures extremely high compressive stress, giving rise to compression failure of the material. Meanwhile, the tensile strength of the test block material is substantially lower than its compressive strength. When the stress wave generated by gas explosion propagates through the material, tensile stress will be induced in certain parts. Once the tensile stress surpasses the tensile strength of the material, the material will experience tensile failure, with the tensile failure predominating the entire failure process. Prior to the gas explosion, the test block resides in a specific initial static stress field, which is dictated by its environment and pre-loading conditions. The high pressure produced by the instantaneous gas explosion will give rise to a potent dynamic stress, and the medium surrounding the gas explosion hole will trigger a compressive stress wave under the impact pressure of the gas explosion. Consequently, the damage caused by gas explosion represents a complex outcome of static and dynamic stress interaction.

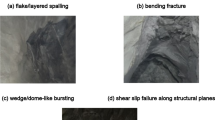

Figure 13(a) and (b) show the cracks and damage of the side wall of the cavern. In the initial stage of excavation, the cavern remains intact and is in the initial stress equilibrium state. After the excavation, due to the sudden formation of the free surface of the tunnel cavern, the radial pressure of the surrounding rock is unloaded and the circumferential pressure is increased, so that the surrounding rock is subjected to tensile failure and the side wall is significantly cracked. The principal cause lies in the fact that the surrounding rock typically possesses a certain tensile and compressive capacity, yet its tensile strength is comparatively low. When the hoop pressure escalates to a particular level, such that the tensile stress surpasses the tensile strength of the surrounding rock, the latter will undergo tensile damage. This concurs with the phenomenon of fragmentation and disintegration observed in certain regions of the surrounding rock subsequent to the completion of drilling and blasting construction in practical engineering. After the excavation is completed, the stress around the cavern is continuously adjusted, and the circumferential pressure continues to increase. The surrounding rock gradually loses its bearing capacity due to different degrees of damage, and the circumferential stress gradually reaches the peak. With the adjustment of surrounding rock stress and energy transfer and dissipation, static rock mass cannot dissipate all energy, part of the energy is released in dynamic form, and finally rock burst occurs after excavation. Figure 11 shows that there is no obvious collapse inside the cavern. This is because the material itself has high brittleness, resulting in only side wall fragmentation and fragment ejection during failure, without large-scale collapse. At the same time, the debris produced by cavern failure contains the information of rock mass failure form, and the size and quantity of debris are one of the important indexes to evaluate the degree of cavern failure. From the perspective of energy theory, during the stress adjustment process of the surrounding rock, there is concomitant energy transfer and dissipation. Prior to excavation, a certain amount of elastic strain energy is stored in the surrounding rock. The stress variation induced by excavation prompts this portion of energy to commence redistribution, with a part of the energy being dissipated through rock deformation, crack propagation and other means. Nevertheless, due to the restricted energy dissipation capacity of the static rock mass, it is infeasible to fully dissipate all the amassed energy. When the accumulated energy surpasses the self-adjustment ability of the rock mass, the excess energy will be released in a dynamic fashion. For instance, cracks emerge in the surrounding rock during the test, and fragments are ejected.

In the test, it was found that the rock burst debris in the large-scale model test is similar to the falling stones in the vault after excavation of the actual project, as shown in Fig. 10. This resemblance indicates that, to a certain degree, the model test is capable of emulating the rock - burst phenomenon in practical engineering. This provides an effective reference for the study of the rock - burst mechanism. When the applied load is low, the internal stress variation within the rock mass is relatively minor, and the crack propagation rate is slow. At this stage, the rock at the free surface gradually exfoliates from the surface under the influence of stress, giving rise to a phenomenon akin to “onion - peel shedding.” When the load is low, the stress within the rock is insufficient to cause large - scale damage to the entire rock mass; however, it suffices to cause the thin layer on the rock surface to fracture and separate. As the load gradually increases, the internal pressure of the surrounding rock is continuously adjusted. Once the pressure reaches the ultimate load, the micro - cracks inside the rock expand and penetrate rapidly, forming a macroscopic fracture network. The formation of these fracture networks severely impairs the structural integrity of the surrounding rock, and its bearing capacity drops precipitously. Finally, when the surrounding rock can no longer withstand the external load, it will result in the collapse of the cavern and trigger the rockburst phenomenon.

From the perspective of engineering application value, the research findings hold substantial practical significance. In engineering, the traditional approaches to handling rock bursts are often rather passive. Most of these methods involve repair and treatment after a rock burst has occurred. This not only consumes a great deal of manpower, material resources, and time but also seriously endangers the project progress and personnel safety. Based on the rockburst mechanism disclosed by this model test, engineers are enabled to more accurately predict the likelihood and scale of rock bursts prior to construction.

Microstructure analysis

As depicted in Fig. 14, the micrograph of the gas explosion fragment reveals that the ratio of compressive strength to tensile strength of the material employed in this test is approximately 20, indicating that the tensile strength of the material is significantly lower than the compressive strength. Compared with chemical explosives, the peak pressure generated by gas explosion excavation is lower and the action time is longer. Under the effect of the gas explosion blast pressure, the material is compressed and destroyed within a small area of pores. Owing to the low tensile strength of the test block, the main failure type is tensile failure caused by the combined action of static and dynamic stress. It can be seen from Fig. 11 that the fracture of the gas explosion fragment is relatively flat, with small irregular steps and parallel stripe patterns, and there is also a small amount of debris and powder at the fracture. In the process of gas explosion, stress concentration will occur at the tip of the crack formed by material failure, which will lead to the further development of the crack. Due to the large quantity and long duration of the gas explosion gas, a gas wedge is formed so that the main crack continues to expand. Under this action, the material mainly exhibits the characteristics of tensile failure, and the irregular steps and river-like patterns are the microscopic morphology of tensile failure.

As shown in Fig. 15, in the microscopic scanning map of the cavern debris, the surface of the debris section exhibits scratches and step-like lines, and the whole is fluffy. At the same time, there are plate-like fractures, crystal fractures and intracrystalline fractures. The specimens in the test are mainly composed of quartz sand, cement, high-strength gypsum, barite powder (barium sulfate) and water, containing a variety of minerals. Usually, there are cracks between various mineral crystals, and the strength of the crystal itself is greater than that of the cement, so it is easy to crack between the crystal particles and the connection between the crystal and the cement. As the stress increases, cracks first occur in the crystal particle gap and cementation, forming a plate-like fracture. The stress acts on the crystal to make it break and produce intracrystalline cracks. When rockburst occurs, the strong stress wave will lead to crack propagation. With the increase of cracks, they are connected and intertwined with each other. At the same time, the debris and powder appearing at the fracture are caused by shear failure and shear slip friction. According to the microscopic morphology of debris generated by rockburst, the failure mechanism of the sur-rounding rock mainly comprises tensile failure and shear failure. Due to the strong stress generated by rockburst, the surrounding rock is subjected to shear and tensile stress simultaneously, forming a tearing effect, which leads to the complex microscopic morphology of the debris.

Test results

Stress test results

Figure 16 presents the results of the stress tests. It can be inferred from the stress test results that under the action of \({\sigma _x}\),\({\sigma _y}\)and\({\sigma _z}\) synchronous gradient loading, the radial measurement points of the cavern were subjected to pressure and the stress exhibited significant variations.

Before the gas explosion excavation, with the increment of the pressure applied in the three directions of \({\sigma _x}\),\({\sigma _y}\)and\({\sigma _z}\), the pressure inside the specimen progressively increases. At this stage, the internal pores of the rock are gradually compacted, and the elastic energy input by the test system is continuously stored within the specimen. The specimen shows no obvious damage, and the stress change ascends steadily. It is notable that the stress at the measuring point 9 cm away from the cavern is greater than that at the measuring point 3 cm away from the cavern, which indicates that the stress of the sample primarily originates from the exterior, while the internal pressure is the outcome of the internal transmission of the external force. Consequently, as the distance from the cavern wall decreases, the stress also diminishes.

When the gas explosion excavation stage is reached, the three - dimensional axial force of the test system is loaded to 20 MPa and the first excavation is conducted. Under the impact of the gas explosion excavation gas, the test block is instantaneously destroyed, and the first section of the tunnel cavern abruptly produces a free surface, resulting in a continuous adjustment of the surrounding stress. According to Fig. 16(a), after the excavation of the first section, the stress of the measuring points at 3 cm and 9 cm from the cavern during the pressure stablisation period decreased from 16.48 MPa and 18.61 MPa to 14.34 MPa and 18.00 MPa, respectively, indicating that the excavation unloading caused the radial pressure of the surrounding rock to decline. After the completion of the second excavation, as shown in Fig. 16(b), the stress of the measuring points at 3 cm and 9 cm from the cavern during the pressure stabilisation period decreased from 16.94 MPa and 20.69 MPa to 15.47 MPa and 19.40 MPa, respectively. This situation renders the surrounding rock more prone to damage, which may lead to the ocurence of rock burst disasters.

The test system continues to apply pressure and the elastic energy stored in the specimen continues to accumulate after the completion of excavation. At T = 11,915 s, the stress at the measuring point 3 cm from the cavern suddenly dropped from 20.69 MPa to 8.96 MPa, a decrease of 56.69%. The pressure values of the other measuring points did not vary significantly. Compaing the monitoring images of the cavern with the acoustic emission results, it can be observed that the surrounding rock at the measuring point 3 cm away from the cavern was damaged, indicating that the surrounding rock of the cavern could not dissipate the stored elastic strain energy, which ultimately led to the destruction of the cavern and the occurrence of the rockburst.

Strain test results

Figure 17 presents the results of the strain test, where the 25–50 cm section is the first excavation section and the 0–25 cm section is the second excavation section. It can be inferred from the figure that there is a minor initial strain inside the specimen prior to loading, which is primarily attributed to the initial strain generated by the optical fibre during the initial setting and hardening process of the concrete36,37. At this moment, initial strain values were negligible (ε < 0.1%), ensuring minimal interference with subsequent data acquisition. As the load augments, the primary pores and cracks within the sample are compacted, the secondary cracks develop, and the strain measured by the fibre optic also increases. In the first section of excavation, the change in internal strain of the sample within 10 min of excavation was recorded by the recording instrument. Figure 17(b) shows that the strain of the first excavated section is notably larger than that of the unexcavated area, and the peak strains at 3 cm and 9 cm from the cavern are 710.78 µε and 503.20 µε, respectively. This is because the cavern deforms under load after the first section was excavated, leading to an increase in strain. After the completion of the second excavation, the free surface inside the tunnel enlarges and the stress around the cavern is continuously adjusted, resulting in further exacerbation of the cavern deformation. At this time, the peak strains of the first excavation area at 3 cm and 9 cm from the cavern are 1080.89 µε and 673.23 µε, respectively, while the peak strains of the second excavation area at 3 cm and 9 cm from the cavern are 1021.89 µε and 660.57 µε, respectively. According to the previous analysis, the failure time of the cavern can be regarded as T = 11,915 s, and the strain of the rock surrounding the cavern is shown in Fig. 17(d). Under the effect of continuous loading, the total strain of the cavern increases significantly, especially at 30.50 cm, the strain at the measuring point 3 cm away from the cavern increases to 1765.97 µε.

Acoustic emission test results

Acoustic emission technology encompasses rich internal damage and energy information of rock, which is of great significance for the analysis of internal crack development and rockburst failure characteristics of rock38,39,40. In this experiment, seven acoustic emission probes were positioned on the specimen to monitor the acoustic emission signals throughout the test. The pre-amplification gain of the acoustic emission is set to 40 dB, and the failure law of the specimen is analyzed by acoustic emission count and energy. The relationship between the stress-time curve and the acoustic emission count and energy during the test is presented in Fig. 18.

-

(1)

Initial compaction stage: During the initial loading, the specimen undergoes three-way compression under the action of the testing machine. Owing to the existence of certain defects and small cracks in the specimen, the internal cracks were compacted during the loading process. At this time, the acoustic emission signal was weak, and the acoustic emission count was 0-0.2 × 10³ times. At this stage, no large cracks were generated inside the specimen, which remained relatively stable, the acoustic emission energy was at a low level, and the failure events were fewer.

-

(2)

Excavation stage: When the excavation conditions (σ = 20 MPa) are reached, the gas explosion method is employed to simulate the drilling and blasting method for excavation. During the first excavation, the acoustic emission count and energy surged to 2.84 × 10³ times and 6.56 × 10⁵ mV·µs in a very short time. This is because the sudden destruction of the excavation area under the action of high-pressure gas during gas explosion excavation, resulting in severe crushing and abnormal acoustic emission activity. After the excavation is completed, the acoustic emission count and energy are significantly reduced. At this time, the tunnel cavern abruptly forms a free surface, and the surrounding rock gradually loses its bearing capacity under the action of radial pressure unloading. The stress of the surrounding rock is continuously adjusted, and the micro-cracks begin to initiate inside the specimen. The acoustic emission activity is more active, and the count and energy are maintained at about 0.4 × 10³ times and 1 × 10⁵ mV·µs. After the second excavation, the acoustic emission count and energy surged to 2.742 × 10³ times and 6.05 × 10⁵ mV·µs, respectively. After the excavation, the count and energy decreased to 0.308 × 10³ times and 0.4 × 10⁵ mV·µs, respectively.

-

(3)

The development of micro-cracks to the rockburst stage: With the increase of stress, the acoustic emission count and energy were maintained at 0.4 × 10³ times and 0.5 × 10⁵ mV·µs, indicating that the micro-cracks inside the specimen began to expand. When the time T = 11,915 s, the acoustic emission count and energy suddenly in-creased to 1.6 × 10³ times and 3.36 × 10⁵ mV·µs. At the same time, the sound of brittle failure was emitted inside the specimen, indicating that the internal damage occurred. Compared with Fig. 13, the free surface inside the tunnel is damaged at this time, and the reason for the active acoustic emission can be attributed to the damage of the surrounding rock around the tunnel. When the load is large, the surrounding rock of the cavern is destroyed, A surge in acoustic emission activity preceded the onset of rockburst, confirming dynamic energy release mechanisms.

By monitoring and analyzing the rockburst process in the model test, key monitoring indicators and parameters, including stress variations and acoustic - emission signals, have been determined. Based on these findings, a more precise rock - burst monitoring and early - warning system has been established for actual projects. This system enables real - time monitoring and early warning of rock bursts, ensuring the safety and smooth progress of project construction, while effectively reducing project costs and risks.

Conclusion

-

(1)

The gas explosion tests have demonstrated that the impact generated by the instantaneous release of pressurized gas is capable of effectively emulating the dynamic load in blasting. When subjected to dynamic loading, the test blocks are instantaneously demolished, accompanied by typical characteristics of dynamic failure manifestations: debris being ejected outwards from the borehole and a conspicuous explosion sound being produced.

-

(2)

During the stress redistribution process of the surrounding rock, the internal energy evolution of the rock mass exhibits two-stage characteristics. In the initial stage, a portion of the energy is dissipated through static mechanisms, while the residual energy is rapidly released in a dynamic form. This constitutes the core disaster-triggering mechanism of rockburst following excavation unloading.

-

(3)

The micro-failure mechanism exhibits the characteristics of tension-shear compounding. In the vicinity of the hole, compression failure prevails, whereas the overall failure mode is governed by the tensile strength of the material. The complexity of the tunnel debris morphology originates from the tearing effect induced by the synergistic interaction of tensile and shear stresses.

-

(4)

The monitoring data of the rockburst test unveiled typical precursors of rockburst: At the measuring point positioned 3 cm away from the cavern, the stress experienced a sudden decline of 56.65% (with the value plummeting from 27.59 MPa to 11.96 MPa). Correspondingly, the strain shot up abruptly to 2207.46 µs. Meanwhile, the acoustic emission parameters demonstrated a stepwise increment (count: 1.6 × 10³, energy: 3.36 × 10⁵ mV·µs), and this was accompanied by the brittle fracture sound emerging from within the rock sample.

Data availability

Data will be provided by corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Z. Z., Gao, F. & Shang, X. J. Rock burst proneness prediction by acoustic emission test during rock deformation. J. J. Cent. South. Univ. 21, 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-014-1950-3 (2014).

Chen, G. Q., He, M. C. & Fan, F. S. Rock burst analysis using DDA numerical simulation. Int. J. Geomech. 18, 4018001. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0001055 (2018).

Li, X. B. et al. Experimental investigation into rock burst proneness of rock materials considering strain rate and size effects. J. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1169750. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2023.1169750 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. Experimental and numerical analysis of rock burst tendency and crack development characteristics of Tianhu granite. J. Geofluids. 2021, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6681261 (2021).

Chen, G. et al. Temperature effect of rock burst for hard rock in deep-buried tunnel. J. Nat. Hazards. 72, 915–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1042-6 (2014).

Zhou, H. et al. Experimental study of the rockburst model material with low-strength and high-brittleness. J. Rock. Soil. Mech. 40, 2039–2049. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2017.1861 (2019).

Zang, W. J., Chang, Y. H. & Wang, Z. Z. Study of similar materials of deep buried hard rock based on dimensional analysis. Chin. J. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 18, 503–512. https://doi.org/10.20174/j.JUSE.2024.03.15 (2022).

Hou, T. K. et al. Experimental study on optimal ratio of similar materials in rock blast. J. Eng. Geol. 14, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.11731/j.issn.1673-193x.2018.11.018 (2018).

Zang, W. J., Chang, Y. H. & Wang, Z. Z. Study of similar materials of deep buried hard rock based on dimensional analysis. J. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 18, 503–512. https://doi.org/10.20174/j.JUSE.2024.03.15 (2022).

Lin, M. Q. et al. Meso-analysis of the rock-burst debris of rock similar material based on SEM. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 9168908. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9168908 (2020).

He, M. et al. Rockburst laboratory tests database—Application of data mining techniques. J. Eng. Geol. 185, 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2014.12.008 (2015).

He, M. C. et al. Development of a testing system for impact rockbursts. Chin. J. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 33, 1729–1739. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2014.09.001 (2014).

He, M. C. et al. Rockburst characteristics based on experimental tests under different unloading rates. J. Rock. Soil. Mech. 35, 2737–2747. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2014.10.001 (2014).

[14] Si, X. F. et al. Experimental simulation on rockburst process of deep three-dimensional circular cavern. J. Rock. Soil. Mech. 39, 621–634. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2017.1057 (2018).

Shu, X. Y. et al. Model tests for deformation and failure characteristics during layered soft rock tunnel excavation under different horizontal stress conditions. J. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 42, 4204–4215. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2022.0746 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Model test study on the mechanical mechanism of strain rockbursts. Chin. J. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 37, 2733–2741. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2018.0266 (2018).

Ortlepp, W. D. & Stacey, T. R. Rockburst mechanisms in tunnels and shafts. J. Tunnelling and underground space technology. Space Technol. 9, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0886-7798(94)90010-8 (1994).

Kaiser, P. K. & Cai, M. Design of rock support system under rockburst condition. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 4, 215–227. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1235.2012.00215 (2012).

Qian, Q. H. Definition, mechanism, classification and quantitative forecast model for rockburst and pressure bump. J. Rock. Soil. Mech. 35, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2014.01.028 (2014).

He, P. F. et al. State-of-the-art review of the rock strength criteria and rock strength experiments subjected to different tensile-compressive stress States. J. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 43, 890–906. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2023.0480 (2024).

Zhou, C. T. et al. A dynamic strength criterion of rock materials based on energy theory. J. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 42, 1890–1898. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2022.1010 (2023).

Xiao, Y. et al. Stiffness theory of rockburst: research progress and trends. J. J. Cent. South. Univ. 30, 4230–4251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-023-5497-z (2023).

Kang, Q. et al. Evaluation of rock burst propensity and rock burst mechanism in deep phosphate mines: A case study of Sujiapo Phosphate Mine, Hubei Province, J. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering. (2022) 7874016. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7874016

An, Y. W. & Yu, M. H. Generalized nonlinear unified strength theory of rock. J. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 48, 616–624. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0258-2724.2013.04.005 (2013).

Brady, B. H. G. & Brown, E. T. Rock mechanics: For underground mining. J. Springer science & business media, (2006). https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-94-011-6501-3

Guo, P. P., Gong, X., Wang, Y., Lin, H. & Zhao, Y. Minimum cover depth Estimation for underwater shield tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 115, 104027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104027 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Time fractal behavior of microseismic events for different intensities of immediate rock bursts. J. Int. J. Geomech. 18, 6018016. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0002035 (2018).

Zhu, C. W., Wu, W., Ying, H. W., Gong, X. N. & Guo, P. P. Drainage-induced ground response in a twin-tunnel system through analytical prediction over the seepage field. Undergr. Space. 7, 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2021.09.004 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Soil heterogeneity effects on Bridge piles deformation under shield tunnelling disturbance. Sustainability 14, 16854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416854 (2022).

Yu, Y., Geng, Y. & Tong, D. Time fractal behavior of microseismic events for different intensities of immediate rock bursts. J. Int. J. Geomech. 18, 6018016. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0001221 (2018).

Xu, L. et al. Study on rock burst characteristics of coal mine roadway in China. J. Energy Sources Part. A. 44, 3016–3035. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2019.1655114 (2022).

Cheon, D. S. et al. Characterization of brittle failure using physical model experiments under polyaxial stress conditions. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 48, 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2010.10.001 (2011).

Zhu, G. Q. et al. Real-time monitoring of the development of brittle fracture in hard rock tunnels based on physical model test. J. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 119, 104240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104240 (2022).

Ren, Y. et al. Review of rock brittleness evaluation methods. J. Oil Geophys. Prospect. 53, 875–886. https://doi.org/10.13810/j.cnki.issn.1000-7210.2018.04.026 (2018).

Kidybiński, A. Bursting liability indices of coal. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 18, 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(81)91194-3 (1981).

Hou, G. Y. et al. Experimental study and engineering application of coupling performance between distributed embedded optical fiber and tunnel lining. Rock. Soil. Mech. 41, 714–726. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2019.0371 (2020).

Wang, H., Xiang, P. & Li, X. Theoretical analysis on strain transfer error of FBG sensors attached on steel structures subjected to fatigue load. Strain 52, 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/str.12195 (2016).

Wang, H. J. et al. Investigation of the fracture modes of red sandstone using XFEM and acoustic emissions. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 85, 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2016.03.012 (2016).

Patricia, R. & Tarcisio, B. C. Application of acoustic emission monitoring and signal analysis to the qualitative and quantitative characterization of the fracturing process in rocks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 27, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.06.027 (2018).

Li, Y. Z. et al. True-triaxial experimental study on the rockburst characteristics of rock mass with a structural plane. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 43, 120–132. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2023.0133 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Open Fund of Engineering Research Center of Ministry of Education of Mine Underground Engineering (No. JYBGCZX2022103). Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2408085ME147).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bin Wang: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Huaqiao Xu: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation. Qinghe Zhang: Resources, Methodology. Zhijun Shen: Resources, Project administration. Yi Jin: Resources, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, B., Xu, H., Zhang, Q. et al. Experimental study on the mechanism of rockburst in tunnel construction by drilling and blasting construction in high ground stress stratum. Sci Rep 15, 8914 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93551-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93551-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Dvelopment and application of similar material for physical model test of an ultradeep foundation pit in round gravel strata

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Numerical analysis of coal rock gas dynamics disaster risk in coal thickness variation area and research on prevention and control

Scientific Reports (2025)