Abstract

Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia occurs in the early stages of the disease and is closely associated with prognosis. Alleviation of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia faces major challenges owing to the lack of preventive and therapeutic drugs that are novel and effective. Urolithin A (UA) is a gut microbial metabolite of ellagic acid that has demonstrated neuroprotective effects in multiple neurological disease models. Nonetheless, the neuromodulatory role of UA in schizophrenia is yet to be elucidated. Wistar rat pups were separated from their mothers for 24 h on postnatal days (PNDs) 9–10 to establish an early-life stress model. The pups were pretreated with UA at different administration times (2, 4, and 6 weeks) and doses (50, 100, and 150 mg/kg) from adolescence (PND29). Behavioral tests were performed after the end of the administration. Subsequently, hippocampal samples were collected for histopathological and molecular evaluations. Male offspring rats subjected to maternal separation exhibited increased sensitivity to prepulse inhibition and cognitive impairment, accompanied by severe neuroinflammation and impaired neurogenesis. However, UA attenuated maternal separation-induced prepulse inhibition deficits and cognitive impairments and restored hippocampal neurogenesis in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, UA pretreatment preserved dendritic spine density, synapses, and presynaptic vesicles. In addition, it exerted anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting microglial activation and expression of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1β. Potential mechanisms included upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein expression and activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway. This study is the first preclinical evaluation of the effects of UA on cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. The findings suggest that changes in cognitive function linked to schizophrenia are driven by the interaction among neuroinflammation, neurogenesis, and synaptic plasticity and that UA has the potential to reverse these processes. These observations provide evidence for future clinical trials of UA as a dietary supplement for preventing schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complex mental illness of unknown etiology that usually develops in adolescence or early adulthood. This condition is characterized by cognitive dysfunction, emotional instability, and impaired social function1, posing a heavy burden on society2. A genome-wide association study observed that immunity and inflammation play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia3. The neurodevelopmental hypothesis proposes that schizophrenia may be linked to neuroinflammation and synaptic plasticity, as evidenced by increased inflammatory cytokines and decreased neurotrophic factors in the serum and brain4.

Epidemiological studies have reported that offspring exposed to stress or infection before or after birth are highly susceptible to schizophrenia in adulthood5. Therefore, stress or immune alterations in early childhood may result in abnormal neurodevelopment and be closely associated with the onset of schizophrenia6,7. Therefore, animal models involving the administration of stress and infectious agents have been designed to mimic certain features of schizophrenia8,9. Studies have shown that the immune system of patients with schizophrenia who experience early-life stress (ELS), such as maternal separation (MS), is more likely to be activated to induce chronic neuroinflammation10. This process is closely related to changes in brain structure and disorders of neural function11. These alterations aggravate the destruction of synaptic transmission and plasticity between neurons and promote oxidative stress, destroying normal cellular function12,13,14. Furthermore, they exert a negative effect on the neurotransmitter system, leading to cognitive impairment and mood instability and exacerbating the risk of schizophrenia15,16.

In recent years, MS has gained increasing recognition as an animal model paradigm for ELS in schizophrenia17,18. MS can initiate a neuroinflammatory response by activating microglia and releasing proinflammatory cytokines [such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α)]. This response affects cognition, memory, and emotion regulation functions by impairing the development of brain regions such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. These regions often exhibit functional and structural abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia19. In addition, the association between neurogenesis and cognitive function has received extensive attention in schizophrenia research. Investigations have established that changes in neurogenesis may play a key role in cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia20. This finding suggests that chronic inflammation and decreased plasticity induced by maternal–infant separation are significant risk factors for schizophrenia. Moreover, it asserts that cognitive impairment in schizophrenia begins in the early stages of the disease. However, none of the currently available drugs can completely improve cognitive impairment in schizophrenia21. In fact, because of the side effects of the drug, cognitive impairment may worsen22,23. Therefore, compounds with anti-neuroinflammatory and neuroprotective effects must be urgently developed to alleviate cognitive impairment in schizophrenia.

Urolithin A (UA) is a natural compound produced by intestinal flora from ellagic acid metabolism. UA has garnered immense research attention in recent years owing to its substantial anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects24. Studies have demonstrated that UA can effectively reduce neuroinflammation, especially in neurodegenerative disease models25,26,27. Our previous study has verified the neuroprotective and therapeutic effects of UA in a D-galactose-induced mouse brain aging model, showing its potential medicinal value28. Nevertheless, reports on the neuromodulatory mechanism of UA in schizophrenia are not available. We speculate that the anti-inflammatory effect of UA can not only improve neurobiological changes but also promote neurogenesis and restore synaptic plasticity in the brain. These alterations may be beneficial in improving schizophrenia-like behaviors and cognitive disorders. The use of UA may serve as a new preventive and therapeutic strategy for alleviating schizophrenia-like behaviors and cognitive disorders caused by ELS, providing a strong theoretical basis for subsequent clinical research.

This study aimed to investigate whether UA can alleviate cognitive and behavioral deficits by reducing neuroinflammation, promoting neurogenesis, restoring synaptic plasticity in the brain, and improving neurobiological changes caused by ELS. The findings are expected to provide novel ideas for treating schizophrenia and promoting the clinical application of UA as a potential drug. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first preclinical study to investigate the effects of UA in a schizophrenia model.

Results

ELS is likely to induce schizophrenia-like behavioral and cognitive impairments in male rats

In Experiment 1 (Fig. 1A), behavioral assessments were performed in MS rats of both sexes (Fig. 2A,D,G and I). The findings revealed that male rats exhibited a decreased novel object recognition rate (Fig. 2C), reduced alternation index (Fig. 2E–F), and increased escape latency (Fig. 2H) in adulthood after 24 h of MS compared with the control group. In the prepulse inhibition (PPI) test, males exhibited impaired PPI at 72, 77, and 82 dB (Fig. 2J–M). However, these impairments were not observed in female rats. In addition, MS reduced the total time spent by male rats in the center of the open field and increased their anxiety-like behavior (Fig. 2B). These observations implied that male rats are more vulnerable to MS than females and exhibit schizophrenia-like behaviors and cognitive impairments. Therefore, male offspring were selected for subsequent experiments.

Male MS rats are more likely to have impaired sensorimotor gating function and cognitive impairment. (A) Schematic diagram of novel object recognition test. (B) Total time that rats in each group entered the center of the open field on the first day of training. (C) Effect of different genders on the object discrimination index in the memory stage of the NOR test. (D) Schematic diagram of the Y-maze test. (E) Total number of times rats entered the three arms respectively. (F) Effect of UA treatment with different time gradients on the alternation rate of spatial working memory in the Y-maze test. (G) Schematic diagram of the Barnes maze test. (H) Escape time of rats entering the target hole during 4 consecutive days of training. (I) Schematic diagram of the PPI test. (J) The left figure shows the baseline startle response to a 120 dB auditory evoked startle stimulus. (K–M) Percentage of auditory startle reflex PPI at 72 dB, 77 dB, and 82 dB after UA treatment with different time gradients. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. MS, maternal separation; NOR, novel object recognition; PPI, prepulse inhibition.

UA reduced learning and memory deficits induced by ELS in rats in a concentration-dependent manner

Subsequently, the effects of UA treatment for different periods and at various concentration gradients on the behavior of MS rats were examined in Experiments 2 and 3 (Fig. 1B and C), respectively. The learning and memory of rats were evaluated using the NOR fixed paradigm (Figs. 3A and 4A). On the first day of training, the total time spent by rats in the MS group in the central area was lower than that of the control group, which indicated MS-induced anxiety-like behavior in rats. However, UA treatment for 4 weeks improved this deficit (Fig. 3B). On the second day of training, no difference was observed in the rats’ exploration time for the two identical objects, and no interest preference was developed (Fig. 4B). In the novel object exploration test, the number of explorations of novel objects and the dwell time were lower in the MS group than in the control group. The discrimination index differed significantly, which implied impaired spatial learning and memory functions. Nonetheless, this defect was attenuated in a dose-dependent manner by UA (50, 100, and 150 mg kg−1, i.g.) (Figs. 3C and 4C). The discrimination index differed among groups across the three administration times. The index did not show a time-dependent attenuation but improved most during the middle period (4 weeks). These results indicate that UA improved the discrimination index of MS rats dose-dependently after 4 weeks of administration and reversed the spatial memory impairment.

Different time gradient UA treatment improves impaired sensorimotor gating and cognitive behavior in MS rats. (A) Schematic of the novel object recognition experiment. (B) On the first day of training, the total time spent by rats in each group entering the center of the open field. (C) The effect of Different concentration gradient UA treatment on the object discrimination index for the memory phases of the NOR test. (D) Schematic of the Y-maze experiment. (E) The total number of times rats entered the three arms respectively. (F) The effect of Different concentration gradient UA treatment on the alternation rate for the Spatial working memory of the Y-maze test. (G) Schematic of the Barnes maze experiment. (H) The escape time of rats entering the target hole during 4 consecutive training days. (I) Schematic diagram of PPI test. (J) The baseline startle response to an auditory-evoked startle stimulus of 120 dB is shown in the left panel. (K–M) Percentage PPI of the auditory startle reflex for 72 dB, 77 dB, and 82 dB after UA treatment with different concentration gradients. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 7). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Different concentration gradient UA treatment improves impaired sensorimotor gating and cognitive behavior in MS rats. (A) Schematic of the novel object recognition experiment. (B) The total time each group spent exploring two identical objects on the second day of adaptation. (C) The effect of Different concentration gradient UA treatment on the object discrimination index for the memory phases of the NOR test. (D) Schematic of the Y-maze experiment. (E) The total number of times rats entered the three arms respectively. (F) The effect of Different concentration gradient UA treatment on the alternation rate for the Spatial working memory of the Y-maze test. (G) Schematic of the Barnes maze experiment. (H) The escape time of rats entering the target hole during 4 consecutive training days. (I) Schematic diagram of PPI test. (J) The baseline startle response to an auditory-evoked startle stimulus of 120 dB is shown in the left panel. (K–M) Percentage PPI of the auditory startle reflex for 72 dB, 77 dB, and 82 dB after UA treatment with different concentration gradients. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 7). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

UA alleviated spatial working memory retention deficits induced by ELS in rats in a concentration-dependent parameter

The Y-maze spontaneous alternation experiment was performed to assess the effect of UA on spatial working memory (Figs. 3D and 4D). No difference was perceived in the total number of alternations (Figs. 3E and 4E). Still, the alternation rate of MS rats was significantly lower than that of control rats, signifying impaired spatial working memory alternation. However, UA treatment (50, 100, and 150 mg kg−1, i.g.) considerably increased the alternation rate in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 3F and 4F). Although the alternation rates of the groups differed across the three administration periods, they did not decrease over time; instead, they were highest in the medium term (4 weeks). These results show that UA dose-dependently improved the alternation rate in rats in the main alternation experiment after 4 weeks of administration and ameliorated the MS-induced spatial working memory defect.

UA reduced spatial memory retention deficits induced by ELS in rats in a concentration-dependent manner

In experiments 2 and 3, the effects of UA administration time and dose gradient differences on the spatial learning and memory abilities of MS rats were evaluated using the Barnes maze test (Figs. 3G and 4G). Starting from the second day, the latency for rats in each group to reach the target hole was shortened. However, the latency to reach the target hole for rats in the MS group was significantly higher than that of the control group, which indicated impaired spatial learning and memory function. UA (50, 100, and 150 mg kg−1, i.g.) attenuated this defect in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 3H and 4H). Although the latency periods of the groups differed across the three administration times, they did not change in a time-dependent manner; instead, they were best during the middle period (4 weeks). These findings assert that UA dose-dependently shortened the latency for rats to enter the target hole after 4 weeks of administration, reversing the MS-induced spatial learning and memory impairment.

UA partially ameliorated prepulse stimulus responses impaired by ELS in rats in a dose-dependent manner

The effects of time and dose gradients of UA administration on PPI in rats were evaluated (Fig. 3I and 4I). Baseline startle responses to 120 dB auditory startle stimulation did not differ between the groups (Figs. 3J and 4J). MS rats showed impaired PPI at different prepulse intensities compared with controls, which signified reduced inhibition of the startle response. Nonetheless, UA attenuated this defect in a dose-dependent manner. Although the startle stimulus of the groups varied across the three administration times, it did not change in a time-dependent manner. In contrast, it improved most during the middle period. These results show that UA dose-dependently reduced the startle response in rats after 4 weeks of administration (Figs. 3K–M and 4K–M). These behavioral results demonstrate that the behavior and cognition of MS rats did not improve significantly after 2 or 6 weeks of UA treatment. However, the improvement was most pronounced after 4 weeks of treatment. In addition, UA treatment enhanced the behavior and cognition of MS rats in a concentration-dependent manner. This finding emphasizes that the precise timing and concentration of administration are crucial to ensure the effectiveness of UA in improving schizophrenia-like behavior and cognitive function in MS rats.

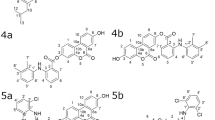

UA preserves dendritic spine density, synapses, and synaptic vesicles of MS rats

It is known that cognitive functional deficits are closely related to the structural alterations of the synapse and dendritic spine density29. Therefore, we next explored the effect of UA on dendritic spine density, synaptic vesicles, and synapses of MS rats in a concentration-dependent manner. As shown in Fig. 5A, dendritic spine density in DG region is selected for analysis (Fig. 5B). The results of Golgi staining revealed that the spine density in hippocampus was significantly decreased in MS animals as compared with control animals. Intriguingly, the decrease of spine density in the hippocampus of MS rats could be significantly preserved by UA. The statistical results are shown in (Fig. 5C). In line with this finding, the numbers of synapses and vesicles per bouton were significantly decreased in MS animals model (Fig. 5D). However, MSanimals with UA pretreatment showed decreased synaptic loss and preserved synaptic vesicles in the presynaptic terminal. The statistical results are shown in Fig. 5E,F.

UA preserves dendritic spine density, synapses, and synaptic vesicles in MS rats in a dose-dependent manner. (A) Representative Golgi-stained images of the hippocampus. (B) Selected dendritic segments from the hippocampus were skeletonized and analyzed using ImageJ software. (C) Quantitative analysis of dendritic spine density in the DG region of the hippocampus. (D) Representative electron microscopy images of synapses in the hippocampus. (E–F) The number of synapses and synaptic vesicles per presynaptic bouton was quantified and analyzed. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus the MS group.

UA treatment enhanced neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of MS rats

Learning and memory processes are intricately associated with hippocampal neurogenesis, and UA can improve hippocampus-dependent cognitive behavioral tasks30,31. Therefore, UA was hypothesized to improve the survival rate of newly formed neurons reduced by ELS. To test this hypothesis, rats were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU on PND29 to label new neurons surviving from puberty to adulthood. The neurogenic potential of the hippocampus was subsequently assessed using BrdU and DCX staining (Fig. 6A). The results showed that compared with the control group, the MS treatment group exhibited a significantly lower survival rate of BrdU-positive (Fig. 6B), DCX-positive (Fig. 6C), and BrdU/DCX double-positive (Fig. 6D) neurons in the hippocampal DG region. These findings indicate the reduced survival of adolescent-born neurons. As expected, UA treatment dose-dependently augmented the survival rate of adolescent-born neurons, considerably reversing this neurogenesis defect.

UA treatment enhanced neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of MS rats. (A) Confocal microscopy images show BrdU-labeled newly generated cells (red), DCX labeled immature neurons (green), and DAPI labeled (blue) in the dentate gyrus. (B) Quantification of BrdU positive cell numbers in the dentate gyrus. (C) Quantitative analysis of DCX positive cell numbers in the dentate gyrus. (D) Quantitative analysis of BrdU/ DCX double positive cell numbers in the dentate gyrus. Data shown are representative images with means ± SEM (n = 3). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, significantly different from control; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, significantly different from MS.

UA Concentration-dependently reduces slleviates gliosis in MS rats

Reactive gliosis is closely related to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia32,33. To determine if UA could influence neuroinflammation in MS rats, we conducted immunofluorescence staining on GFAP-labeled astrocytes and Iba-1-labeled microglia. This allowed us to evaluate microglial activation and reactive astrogliosis in the hippocampus (Fig. 7A). The results indicated a significant increase in the number of Iba-1-labeled microglia in MS rats (Fig. 7B). However, UA administration (50 mg kg−1, 100 mg kg−1, 150 mg kg−1, i.g.) dose-dependently reduced the number of Iba-1-positive cells. Similarly, the number of GFAP-positive cells in the hippocampal DG zone of MS rats was significantly higher compared to the control group. However, UA treatment reduced the number of GFAP-positive cells (Fig. 7C). These findings suggest that UA at various concentrations can effectively alleviate microglial hyperactivity and astrogliosis in MS rats.

UA treatment inhibited the activation and proliferation of microglia and astrocytes in the dentate gyrus of MS rats. (A) Confocal microscopy images show Iba-1-labeled microglia (green), GFAP-labeled astrocytes (red), and DAPI (blue) in the dentate gyrus. Scale bar = 200 μm. Quantitative analysis of Iba-1-positive cells (B) and GFAP-positive cells (C) in the dentate gyrus. Data are single values with mean ± SEM (n = 3). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, significantly different from control; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, significantly different from MS. Iba-1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein.

UA treatment decreases proinflammatory cytokine levels in MS rats

The activation and proliferation of glial cells is one of the causes of schizophrenia34.This process can upregulate the expression of several pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, TGF-β, and TNF-α, which can lead to neuronal death and cognitive deficits35,36. Therefore, we further measured the expression of these three cytokines in the hippocampus of each group. The results showed that, compared to the control group, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were significantly increased in the hippocampus of MS rats (Fig. 8A–C). Interestingly, UA partially attenuated these pro-inflammatory effects in a dose-dependent manner. This demonstrates that UA can inhibit the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, thereby improving cognitive function.

UA treatment decreased the levels of inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in the hippocampus of MS rats, while increasing the expressions of BDNF and p-ERK. (A–C) The expressions of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α mRNA in the cortex and hippocampus were detected by quantitative RT-PCR. (D) Representative Western blot bands in the hippocampal region. (E) Protein expression of BDNF and β-actin as internal controls. (F) Expression of ERK1/2 and β-actin as internal controls. (G) Expression of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and β-actin as internal controls in hippocampus. Specific grouping information is indicated by a combination of “−” and “+”. Data shown are single values with ± SEM (n = 3), #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, significantly different from control; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 significantly different from MS. BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ERK, extracellular regulating kinase; p-ERK, phosphorylated ERK.

UA treatment increasing expression of BDNF and phosphorylated-ERK

The BDNF/ERK signaling pathway is extensively involved in learning and memory processes, playing a critical role in regulating synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis37. To further investigate whether the neuromodulatory mechanism of UA in the MS model involves the activation of the BDNF/ERK pathway, we assessed the levels of BDNF, ERK, and phosphorylated ERK (Fig. 8D). The results indicated that protein expression levels of BDNF, ERK1/2, and phosphorylated ERK1/2 were decreased in the MS group compared to the control group. As anticipated, UA treatment increased BDNF expression and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8E–G), suggesting that UA-induced alterations in these pivotal signaling proteins may contribute to its neuroprotective effects in schizophrenia.

Discussion

Currently, numerous opportunities and challenges exist in developing drugs to improve cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. This study revealed that UA promotes neurogenesis and preserves spine density, synapses, and presynaptic vesicles in a dose-dependent manner while simultaneously enhancing spatial learning and working memory in hippocampus-dependent tasks affected by MS. This effect was achieved by reducing gliosis and the expression of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. The mechanisms involved the upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway. These findings suggest that UA is a promising natural dietary supplement for preventing cognitive impairment in schizophrenia.

Patients with schizophrenia are known to exhibit dysfunction in spatial learning and memory38. Increasing evidence suggests that ELS plays a key role in the development of schizophrenia39,40. Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that 24-h MS in Wistar rats on PND9 can impair PPI and spatial and working memory tasks41. This study observed that the behavior and cognition of male and female offspring rats were affected under the same stress conditions. However, males appeared more sensitive than females and were more likely to develop behavioral and cognitive impairments, which agrees with earlier studies42. Whether this sex-based difference could be attributed to the complex neuroprotective effects of estrogen requires further investigation.

Dendritic spine loss is closely associated with cognitive decline43,44. The findings from this study indicated a significant reduction in dendritic spines in the hippocampus of MS rats. UA markedly mitigated dendritic spine loss in a concentration-dependent manner. A previous study has asserted that even in the early stages of the disease, patients with schizophrenia exhibit a significant reduction in synapses45. Studies have recorded the loss of both the presynaptic marker synaptophysin and the postsynaptic marker myelin in a rat model of schizophrenia46. In line with these findings, this investigation identified that synapses in the hippocampus of MS rats were considerably decreased. Interestingly, UA pretreatment preserved synapses in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, earlier studies have documented mutations in the synaptogyrin 1 gene in families with schizophrenia. This observation suggests that impaired synaptic transmission is an integral part of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia47,48. Similarly, a reduction in presynaptic vesicles was noted in MS rats in this study. UA could preserve presynaptic vesicle stores in a concentration-dependent manner. As cognitive functions develop from adolescence to early adulthood, UA pretreatment may help shape neural circuits by eliminating redundant synapses formed during early development and strengthening the remaining ones, which ultimately improves cognition.

Learning and memory processes are intricately linked to hippocampal neurogenesis49. Newly born dentate granule cells play a role in hippocampal function by integrating into neural circuits50. UA has been reported to substantially increase the proliferation of neuronal precursors and promote their differentiation into neurons after ischemic stroke, thereby improving cognitive function51. Consistent with animal behavioral tests, immunofluorescence results showed that MS inhibited the proliferation and differentiation of rat glial cells. This observation was supported by the reduced number of BrdU- and DCX-positive cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. UA ameliorated this neurogenic deficit by stimulating neurogenesis in adulthood. The effect of UA on improving behavior and cognition in MS rats could at least partially be attributed to the regulation of neurogenesis.

Immune imbalance and subsequent neuroinflammation are essential components in the pathology of schizophrenia52,53. Like Alzheimer’s disease (AD), schizophrenia is often associated with dysregulated immune responses and chronic inflammation in the central nervous system25. Certain patients with AD display core disease features akin to schizophrenia, such as white matter abnormalities and progressive cognitive decline54. This finding signifies a potential overlap in immune dysfunction and neuroinflammation between schizophrenia and AD, implying shared etiological and therapeutic implications.

Microglia, astrocytes, and inflammatory cytokines in the brain mediate neuroinflammation. These become activated after chronic stress or injury and enhance the production of proinflammatory cytokines55. According to the neuroimmune hypothesis of schizophrenia, gliosis amplifies neuroinflammatory signals and exacerbates psychopathological symptoms and cognitive deficits56. Along with mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, neuroinflammation creates a vicious cycle that fosters the development of schizophrenia57,58. Studies have shown that UA inhibits microglial and astrocytic activation in animal models such as AD and acute ischemic stroke59,60. In line with these observations, this study found a substantial increase in Iba1- and GFAP-labeled microglia and astrocytes in the hippocampus of MS rats. This finding suggests that early-life environmental stress may heighten susceptibility to schizophrenia pathology by activating neuroinflammation and impairing cognition. Nonetheless, UA might reverse this process by inhibiting microglial and astrocytic activation and alleviating the release and infiltration of proinflammatory cytokines. Therefore, the potential anti-inflammatory effects of UA could ameliorate neuropsychiatric disease pathology and confer neuroprotection to augment cognitive function.

As a result of the increased permeability of the blood–brain barrier, patients with schizophrenia are susceptible to invasion by peripheral immune cells and cytokines61. This invasion leads to impaired neuroplasticity and neurogenesis62. Studies have observed that UA directly downregulates the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 by activating microglia and upregulating the production of BDNF via the PKA/CREB/BDNF neurotrophic signaling pathway63,64. The findings illustrated that TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels were increased in the hippocampus of MS rats, which were negatively correlated with their neurogenesis potential. Conversely, UA dose-dependently attenuated TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels. Therefore, UA exerts anti-inflammatory and neurogenesis-promoting effects.

BDNF is involved in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and cognitive function65,66. Several studies have established that BDNF levels are reduced in the peripheral blood of patients with schizophrenia, whereas the levels of inflammatory factors are increased67,68,69. In this study, BDNF expression levels were downregulated and inflammatory factor levels were upregulated in MS rats, which suggests that MS induces cognitive deficits by reducing BDNF signals and increasing inflammatory factors. UA has been reported to provide cognitive protection by decreasing neuroinflammation and stimulating mitochondrial function in sleep deprivation-induced mice63. Therefore, reduced BDNF levels and increased inflammatory factors often coexist. Although the interaction between BDNF and inflammatory factors should be investigated further, this synergistic effect may be one of the mechanisms responsible for cognitive impairment and behavioral abnormalities in schizophrenia.

In addition, BDNF is implicated in the cascade upstream of ERK and plays a crucial role in synaptic plasticity70,71,72. In this study, ERK signaling was downregulated simultaneously with BDNF expression in MS rats, which signifies that MS induces cognitive deficits by reducing BDNF/ERK signaling and impairing neurogenesis. Hence, UA’s improvement in the learning and memory function of MS rats could be associated with BDNF/ERK signaling recovery.

This study has several limitations. First, the many behavioral tests, which took 9 days, may not fully represent the immediate effects after treatment. Second, our current observations do not provide evidence that UA’s anti-inflammatory and neurotrophic properties are directly or causally related to its preventive and therapeutic effects on cognitive function. Finally, the pathogenesis of schizophrenia is complex and unclear and is believed to result from genetic and gene–environment interactions73,74. The neurodevelopmental animal model employed in this study, which focuses on cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, may not fully reproduce the complex and heterogeneous etiology of the disease. Therefore, the timing of behavioral assessments should be rationally designed in future studies, starting with mechanistic research. The specific relationship between UA’s anti-inflammatory and neurotrophic properties and its cognitive improvement effects must be clearly demonstrated.

Our study is the first to illustrate that UA can improve schizophrenia-like behaviors and learning and memory deficits caused by MS. The findings highlighted the ability of UA to modulate neuroinflammatory and neurogenic synaptic plasticity in a rat model of schizophrenia. Thus, UA supplementation may be a promising therapeutic approach to enhance cognitive function in psychiatric disorders. However, this is our first preclinical study of UA’s potential to alleviate schizophrenia-like behaviors and cognitive impairment. Further long-term and in-depth studies are required to clarify the potential preventive role of UA in schizophrenia.

Materials and methods

Animals

Numerous studies have shown that early life stress can affect behavior and cognition in Wistar rats, a process induced by the maternal separation (MS) procedure. Specifically, the dam was removed from the home cage at 10:00 AM on PND9, and the pups were left alone in their home cages until 10:00 AM the next day, when the dam was returned75,76. Twenty nulliparous female and ten male 10-week-old Wistar rats were purchased from Beijing Vital Rival Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. and housed in an SPF animal facility under controlled temperature (22 °C) and humidity (60%) conditions. The light–dark cycle was maintained at 12 h each. All animals had free access to standard laboratory food and water. At 11 weeks of age, the animals were mated at a 1:2 male-to-female ratio, and the male rats were removed one week later. Female rats were housed individually three days before the expected delivery date and checked twice daily for delivery at 08:00 and 17:00. The day of delivery was considered postnatal day (PND0). MS was carried out following the established protocol of our laboratory75. The control group was allowed to develop naturally until puberty. On PND21, all pups were weaned, randomly assigned to groups, and housed with same-sex littermates (4–5 per cage).

Experimental design

Experiment 1: Establishing a rat model of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. First, to obtain a stable rat model of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, we divided the offspring of the MS rats into female and male MS groups based on gender at PND 21 (n = 5 per group). The control group was allowed to develop naturally into adulthood. Behavioral tests were conducted after reaching adulthood (PND 56) as shown in Figs. 1A and S1.

Experiment 2: Effects of different UA treatment durations on behavior and cognition in MS rats.Then, in Experiment 2, based on the results of Experiment 1 and our previous work77, we selected an appropriate intermediate concentration (100 mg kg−1) and established three different treatment duration groups (2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 6 weeks) to study the effects of various UA treatment times on the behavior and cognition of the schizophrenia rat model. The experiment was divided into five groups(n = 7 per group) : ontrol group, model group, 2-week UA treatment group, 4-week UA treatment group, and 6-week UA treatment group. The control group received normal saline (10 ml kg-1 day-1) as the vehicle control. All rats underwent behavioral tests after the treatment and were then sacrificed. The experimental process is shown in Figs. 1B and S2.

Experiment 3: Effects of different UA treatment concentrations on behavior, cognition, and related pathological phenotypes in MS rats. Finally, the behavioral results from Experiments 1 and 2 were summarized to further investigate the effects of different UA concentration gradients on schizophrenia-like behaviors, cognitive function, and pathology in rats. The experiment was divided into 6 groups(n = 7 per group) : the control group (Con + saline), the model group (MS + saline), the positive control group (MS + risperidone 0.1 mg kg−1), the low-dose group (MS + UA 50 mg kg-1), the medium-dose group (MS + UA 100 mg kg−1), and the high-dose group (MS + UA 150 mg kg−1). Each MS group received UA and risperidone by gavage from PND 29 to PND 56. The control group was treated with saline (10 ml kg−1 day−1) as a vehicle control. After completion of UA administration, behavioral tests were conducted, and then the rats were sacrificed, and tissues were collected. The time course of the experimental process is shown in Figs. 1C and S3.

Drug administration

UA (U287598, Aladdin, China) was dispersed in 0.5% sodium carboxymethylcellulose (CMC-Na) (C104985, Aladdin, China), and risperidone was diluted in saline, with all drugs prepared fresh daily. The dosing schedule followed the established protocol. In Experiment 3, three animals from each group received two intraperitoneal injections of BrdU (100 mg kg−1) (B110731, Aladdin, China) on PND29, spaced 2 h apart. This ensured consistent BrdU incorporation rates between the control and MS groups, effectively labeling proliferating cells78.Behavioral testing began at the end of drug treatment. After tissue collection, the brain was perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and sectioned for immunofluorescence analysis.

Behavioral testing

Behavioral testing began the day following the completion of drug treatment. To avoid interference between tests, they were conducted in the following sequence: Novel Object Recognition, Y-maze, Barnes Maze, and PPI. All behavioral tests were conducted between 08:00 and 20:00. After each test, the rats were provided with sufficient time for acclimatization and rest to ensure the independence of each test. The equipment was cleaned with 75% ethanol after each trial. Detailed behavioral protocols are provided in the supplementary materials (Figure S4).

Sample collection

After the behavioral test,all groups of rats were euthanized using sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.).Three animals in each group that had been injected intraperitoneally with BrdU on PND 29 were perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and their brains were removed for immunofluorescence analysis. The hippocampal tissues of the remaining rats in each group were removed, immediately frozen on dry ice, and then transferred to − 80 °C for storage until the subsequent protein expression analysis.

Spine density analysis

Golgi staining was used to examine changes in spine density. Briefly, intact brain tissue was quickly dissected from the skull under deep anesthesia. The surface blood was rinsed off with distilled water, and the brain was immediately immersed in pre-prepared Golgi staining fixative (G1069-15ML, Servicebio, China) and stored in the dark at room temperature for 14 days. The brain was then transferred to tissue processing solution and stored at room temperature for 3 days. Coronal whole-brain sections, 60 μm thick, were mounted on gelatin-coated slides with tissue processing solution and left to air-dry at room temperature for 2 days. After rinsing with distilled water, Golgi developing solution was applied to the brain sections and incubated for 30 min. Following a final rinse, the sections were mounted with glycerol gelatin. Images were captured at 100Ítotal magnification using Pannoramic Scanner software. Dendritic spines were processed and analyzed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) software. For each group, three animals were included in the spine density analysis, and the experimenter was blinded to the data during all tests.

Transmission electron microscopy

Under deep anesthesia, the rat brain was quickly removed, and the hippocampus was extracted within 1–2 min. The hippocampus was cut into 1 mm3 tissue blocks in a culture dish using a scalpel, and the blocks were then transferred to an EP tube containing electron microscope fixative (G1102, Servicebio, China) for fixation. After being kept at room temperature for 2 h, the tissue was fixed and stored at 4 °C. Subsequently, the tissue was post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4) at room temperature in the dark for 7 h. The tissue was then dehydrated sequentially with 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, and 100% alcohol, each step lasting 1 h. After penetration and embedding, the embedding plate was placed in a 60 °C oven for polymerization for 48 h, after which the resin block was removed. The resin block was sectioned into 60–80 nm ultrathin slices using an ultramicrotome, and the slices were mounted on 150-mesh copper grids coated with a Formvar membrane. The grids were stained with a 2% uranyl acetate saturated alcohol solution in the dark for 8 min, washed three times with 70% alcohol, rinsed three times with ultrapure water, then stained with 2.6% lead citrate in the dark for 8 min, followed by three washes with ultrapure water. The grids were gently dried with filter paper and left to air-dry overnight at room temperature. The sections were observed under a transmission electron microscope (TEM), and images were collected for analysis. Images at both low and high magnification were captured using a Hitachi TEM system at 80 kV. For each group, three animals were included in the analysis.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from hippocampal tissues with protein lysis buffer (G2002, Servicebio, China). The protein concentration was determined with a BCA kit (E-BC-K318-M, Elabscience, China). The proteins in each sample were separated by 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Western blot analysis was performed using the following primary antibodies raised against target proteins: rabbit anti-BDNF (1:2000, 66292-1-IG, Proteintech), rabbit anti-Erk1/2 (1:1000, T40071, Abmart), rabbit anti-phospho-Erk1 (T202/Y204) + Erk2 (T185/Y187) (T40072, Abmart), and rabbit anti-β-actin (1:2000, P30002, Abmart) antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10000 dilution, HY-P8001, MedChemExpress) was used. Western blotting substrates were visualized using ECL reagents with enhanced chemiluminescence detection and the Chemidoc™ Touch Imaging System with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). When several target proteins have similar molecular weights, we use the western blot fast stripping buffer (EpiZyme, Shanghai, China, PS107) for treatment and re-blocking. We declare and ensure that our western blot data comply with the digital image and integrity policies.

Tissue preparation and immunofluorescence staining

Rats were anesthetized and perfused through the heart initially with PBS and then with 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was then post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Brain tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. The paraffin-embedded tissue sections were dewaxed in xylol, rehydrated, placed in sodium citrate, microwaved for antigen retrieval, washed with PBS, and then blocked with 1% BSA (A8020, Solarbio, China) in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-BrdU (1:200 ab152095, Abcam), mouse anti-doublecortin (DCX) (1:50 sc-271390, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:500 GB15096, Servicebio) and rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:500 GB113502, Servicebio). followed by incubation with an CY3-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:300, GB21301, Servicebio) or CY3-labeled goat anti- mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:300, GB21303, Servicebio), and Alexa Fluor-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:400, GB25303, Servicebio) or Alexa Fluor-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:400, GB25301, Servicebio) and DAPI (G1012, Servicebio) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the sample slices were mounted on glass slides using a fluorescence mounting medium (G1401, Servicebio).

Cell counts and quantification

A modified unbiased stereology protocol was used for BrdU, DCX, Iba-1, and GFAP quantification79,80. One out of every five adjacent sections throughout the hippocampus was chosen and processed for immunohistochemistry. The number of positive cells in the dentate gyrus layer and hilus throughout the hippocampus was imaged using confocal microscopy (TCS SP8, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) or Pannoramic MIDI digital scanners (3D HISTECH Ltd., Budapest, Hungary). The results were expressed as the average number of positive cells per section and analysed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) by an independent researcher.

Real time qPCR analysis

Total RNA from rat HPC in each group was extracted with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, California, USA) followed by chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation. The RNA was resuspended in nuclease-free water, and its concentration and purity were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). Then, total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR(+ gDNA wiper) Kit (R323-01, Vazyme, Shanghai, China). And the RNA/reagent mixture was incubated at 42 °C for 1 h, further heated to 70 °C for 5 min, and then cooled to 48 °C. The mRNA expression levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and GADPH were measured by RT-qPCR on a Bio-Rad Connect platform. GADPH was used as an internal reference control. 1.2 μL of cDNA was added to 20 μL of reaction mixture with 0.4 μL pre-primer and 0.4 μL post-primer according to the instructions of the commercial kit Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q712-02, Vazyme, Shanghai, China). The incubation conditions for each cycle of PCR were 95 °C for 5 min for initial denaturation, then 95 °C for 10 s for denaturation, and 90 °C for 30 s for annealing and extension, for a total of 40 cycles. Melting curve analysis was performed after the final amplification step to verify the specificity of the primers. The reaction was carried out in triplicate. The primers and their sequences used in this study are described in Table 1.

Data analysis and statistics

Sample size for statistical analysis was at least five animals per group. For Western blot analysis, each sample was run in triplicate. The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was used to assess the normality of the data. The effect of UA treatment on escape latency in the Barnes maze was analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA. For non-parametric data, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. All other comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Post hoc tests were performed only when the Kruskal–Wallis test or F in ANOVA reached the required level of statistical significance and there was no significant variance in homogeneity. Data Analysis and Statistics Data are presented as means ± SEM and were analyzed using SPSS Statistics v20.0 (IBM Statistics, New York, USA. https://hlbafx.com/1612.html) and Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., California, USA. http://www.graphpad-prism.cn/). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Ethical approval

All animal experiments complied with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines, we made every effort to minimize animal pain and discomfort, and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Renmin Hospital, Wuhan University. The approved protocol number is WDRM20230310D.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reason- able request.

References

Kahn, R. S. On the origins of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 177(4), 291–297 (2020).

Howes, O. D., Bukala, B. R. & Beck, K. Schizophrenia: From neurochemistry to circuits, symptoms and treatments. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 20(1), 22–35 (2024).

Sekar, A. et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature 530(7589), 177–83 (2016).

Mattei, D. et al. Minocycline rescues decrease in neurogenesis, increase in microglia cytokines and deficits in sensorimotor gating in an animal model of schizophrenia. Brain Behav. Immun. 38, 175–184 (2014).

Giovanoli, S. et al. Stress in puberty unmasks latent neuropathological consequences of prenatal immune activation in mice. Science 339(6123), 1095–1099 (2013).

Rowshan, N., Anjomshoa, M., Farahzad, A., Bijad, E. & Amini-Khoei, H. Gut-brain barrier dysfunction bridge autistic-like behavior in mouse model of maternal separation stress: A behavioral, histopathological, and molecular study. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 84(4), 314–327 (2024).

Gyorffy, B. A. et al. Widespread alterations in the synaptic proteome of the adolescent cerebral cortex following prenatal immune activation in rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 56, 289–309 (2016).

Estes, M. L. & McAllister, A. K. Maternal immune activation: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science 353(6301), 772–777 (2016).

Ben-Azu, B. et al. Morin decreases cortical pyramidal neuron degeneration via inhibition of neuroinflammation in mouse model of schizophrenia. Int. Immunopharmacol. 70, 338–353 (2019).

Guerrin, C. G. J., Doorduin, J., Sommer, I. E. & de Vries, E. F. J. The dual hit hypothesis of schizophrenia: Evidence from animal models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 131, 1150–1168 (2021).

Reisi-Vanani, V., Lorigooini, Z., Bijad, E. & Amini-Khoei, H. Maternal separation stress through triggering of the neuro-immune response in the hippocampus induces autistic-like behaviors in male mice. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 84(2), 87–98 (2024).

Amini-Khoei, H. et al. Therapeutic potential of Ocimum basilicum L. extract in alleviating autistic-like behaviors induced by maternal separation stress in mice: Role of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Phytother. Res. 39(1), 64–76 (2025).

Ben-Azu, B. et al. Taurine, an essential beta-amino acid insulates against ketamine-induced experimental psychosis by enhancement of cholinergic neurotransmission, inhibition of oxidative/nitrergic imbalances, and suppression of COX-2/iNOS immunoreactions in mice. Metab. Brain Dis. 37(8), 2807–2826 (2022).

Ben-Azu, B. et al. Containment of neuroimmune challenge by diosgenin confers amelioration of neurochemical and neurotrophic dysfunctions in ketamine-induced schizophrenia in mice. Brain Disord. 13, 100122 (2024).

Ben-Azu, B. et al. Effective action of silymarin against ketamine-induced schizophrenia in male mice: Insight into the biochemical and molecular mechanisms of action. J. Psychiatr. Res. 179, 141–155 (2024).

Ben-Azu, B. et al. Antipsychotic effect of diosgenin in ketamine-induced murine model of schizophrenia: Involvement of oxidative stress and cholinergic transmission. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 16, 86–97 (2024).

Oginga, F. O. & Mpofana, T. The impact of early life stress and schizophrenia on motor and cognitive functioning: An experimental study. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 17, 1251387 (2023).

Xu, S. et al. Capsaicin alleviates neuronal apoptosis and schizophrenia-like behavioral abnormalities induced by early life stress. Schizophrenia (Heidelb) 9(1), 77 (2023).

Esslinger, M. et al. Schizophrenia associated sensory gating deficits develop after adolescent microglia activation. Brain Behav. Immunol. 58, 99–106 (2016).

Na, K. S., Jung, H. Y. & Kim, Y. K. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the neuroinflammation and neurogenesis of schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 48, 277–286 (2014).

Falkai, P. et al. Disturbed oligodendroglial maturation causes cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: A new hypothesis. Schizophr. Bull. 49(6), 1614–1624 (2023).

Gebreegziabhere, Y., Habatmu, K., Mihretu, A., Cella, M. & Alem, A. Cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia: An umbrella review. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 272(7), 1139–1155 (2022).

McCutcheon, R. A., Keefe, R. S. E. & McGuire, P. K. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: Aetiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 28(5), 1902–1918 (2023).

Gandhi, G. R. et al. Health functions and related molecular mechanisms of ellagitannin-derived urolithins. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 64(2), 280–310 (2024).

Ahsan, A. et al. Natural compounds modulate the autophagy with potential implication of stroke. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11(7), 1708–1720 (2021).

Romo-Vaquero, M. et al. Urolithins: Potential biomarkers of gut dysbiosis and disease stage in Parkinson’s patients. Food Funct. 13(11), 6306–6316 (2022).

An, L., Lu, Q., Wang, K. & Wang, Y. Urolithins: A prospective alternative against brain aging. Nutrients 15(18), 3884 (2023).

Chen, P., Chen, F., Lei, J., Li, Q. & Zhou, B. Activation of the miR-34a-mediated SIRT1/mTOR signaling pathway by urolithin A attenuates D-galactose-induced brain aging in mice. Neurotherapeutics 16(4), 1269–1282 (2019).

Villeda, S. A. et al. Young blood reverses age-related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nat. Med. 20(6), 659–663 (2014).

Collado-Torres, L. et al. Regional heterogeneity in gene expression, regulation, and coherence in the frontal cortex and hippocampus across development and schizophrenia. Neuron 103(2), 203–216 (2019).

Peterson, B. S. et al. Aberrant hippocampus and amygdala morphology associated with cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 17, 1126577 (2023).

Okamura, Y. et al. Tau progression in single severe frontal traumatic brain injury in human brains. J. Neurol. Sci. 407, 116495 (2019).

Dinesh, A. A., Islam, J., Khan, J., Turkheimer, F. & Vernon, A. C. Effects of antipsychotic drugs: Cross Talk between the nervous and innate immune system. CNS Drugs 34(12), 1229–1251 (2020).

Dietz, A. G., Goldman, S. A. & Nedergaard, M. Glial cells in schizophrenia: A unified hypothesis. Lancet Psychiatry 7(3), 272–281 (2020).

Laricchiuta, D. et al. The role of glial cells in mental illness: A systematic review on astroglia and microglia as potential players in schizophrenia and its cognitive and emotional aspects. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 18, 1358450 (2024).

Comer, A. L., Carrier, M., Tremblay, M. E. & Cruz-Martin, A. The inflamed brain in schizophrenia: The convergence of genetic and environmental risk factors that lead to uncontrolled neuroinflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 14, 274 (2020).

Leal, G., Comprido, D. & Duarte, C. B. BDNF-induced local protein synthesis and synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology 76 Pt C, 639–56 (2014).

Ding, Y. et al. Core of sensory gating deficits in first-episode schizophrenia: Attention dysfunction. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1160715 (2023).

Perrin, M., Kleinhaus, K., Messinger, J. & Malaspina, D. Critical periods and the developmental origins of disease: An epigenetic perspective of schizophrenia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1204, E8-13 (2010).

Rivollier, F., Lotersztajn, L., Chaumette, B., Krebs, M. O. & Kebir, O. Epigenetics of schizophrenia: A review. Encephale 40(5), 380–386 (2014).

Hao, K. et al. The role of SIRT3 in mediating the cognitive deficits and neuroinflammatory changes associated with a developmental animal model of schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 130, 110914 (2024).

Brand, B. A., de Boer, J. N. & Sommer, I. E. C. Estrogens in schizophrenia: Progress, current challenges and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 34(3), 228–237 (2021).

Sellgren, C. M. et al. Increased synapse elimination by microglia in schizophrenia patient-derived models of synaptic pruning. Nat. Neurosci. 22(3), 374–385 (2019).

Cornell, J., Salinas, S., Huang, H. Y. & Zhou, M. Microglia regulation of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. Neural Regen. Res. 17(4), 705–716 (2022).

Wang, M., Zhang, L. & Gage, F. H. Microglia, complement and schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 22(3), 333–334 (2019).

Breach, M. R., Dye, C. N., Galan, A. & Lenz, K. M. Prenatal allergic inflammation in rats programs the developmental trajectory of dendritic spine patterning in brain regions associated with cognitive and social behavior. Brain Behav. Immun. 102, 279–291 (2022).

Landen, M. et al. Reduction of the small synaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin but not the large dense core chromogranins in the left thalamus of subjects with schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 46(12), 1698–1702 (1999).

Verma, R. et al. A nonsense mutation in the synaptogyrin 1 gene in a family with schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 55(2), 196–199 (2004).

Hu, L. & Zhang, L. Adult neural stem cells and schizophrenia. World J. Stem Cells 14(3), 219–230 (2022).

Yang, C. H. et al. Circuit integration initiation of new hippocampal neurons in the adult brain. Cell Rep. 30(4), 959–968 (2020).

Gong, Z. et al. Urolithin A attenuates memory impairment and neuroinflammation in APP/PS1 mice. J. Neuroinflam. 16(1), 62 (2019).

Rantala, M. J., Luoto, S., Borraz-Leon, J. I. & Krams, I. Schizophrenia: The new etiological synthesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 142, 104894 (2022).

Buckley, P. F. Neuroinflammation and schizophrenia. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21(8), 72 (2019).

Kochunov, P. et al. A white matter connection of schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Schizophr. Bull. 47(1), 197–206 (2021).

Kim, Y. S., Choi, J. & Yoon, B. E. Neuron-Glia interactions in neurodevelopmental disorders. Cells 9(10), 2176 (2020).

Singh, D. Astrocytic and microglial cells as the modulators of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 19(1), 206 (2022).

Arena, G. et al. Neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease: A self-sustained loop. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 22(8), 427–440 (2022).

Joshi, A. U. et al. Fragmented mitochondria released from microglia trigger A1 astrocytic response and propagate inflammatory neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 22(10), 1635–1648 (2019).

Ballesteros-Alvarez, J., Nguyen, W., Sivapatham, R., Rane, A. & Andersen, J. K. Urolithin A reduces amyloid-beta load and improves cognitive deficits uncorrelated with plaque burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Geroscience 45(2), 1095–1113 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Urolithin A protects dopaminergic neurons in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease by promoting mitochondrial biogenesis through the SIRT1/PGC-1alpha signaling pathway. Food Funct. 13(1), 375–385 (2022).

Campana, M. et al. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction and folate and vitamin B12 levels in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis: A retrospective chart review. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 273(8), 1693–1701 (2023).

Khandaker, G. M. et al. Inflammation and immunity in schizophrenia: Implications for pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry 2(3), 258–270 (2015).

Misrani, A., Tabassum, S., Zhang, Z. Y., Tan, S. H. & Long, C. Urolithin A prevents sleep-deprivation-induced neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in young and aged mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 61(3), 1448–1466 (2024).

An, L. et al. Walnut polyphenols and the active metabolite urolithin A improve oxidative damage in SH-SY5Y cells by up-regulating PKA/CREB/BDNF signaling. Food Funct. 14(6), 2698–2709 (2023).

Chen, Y. H. et al. Quetiapine and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation ameliorate depression-like behaviors and up-regulate the proliferation of hippocampal-derived neural stem cells in a rat model of depression: The involvement of the BDNF/ERK signal pathway. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 136, 39–46 (2015).

Yao, W. et al. Microglial ERK-NRBP1-CREB-BDNF signaling in sustained antidepressant actions of (R)-ketamine. Mol. Psychiatry 27(3), 1618–1629 (2022).

Dai, N. et al. Different serum protein factor levels in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia characterized by positive and negative symptoms. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 74(9), 472–479 (2020).

Huang, Z. et al. Predictive effect of Bayes discrimination in the level of serum protein factors and cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr Res. 151, 539–545 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Study on correlations of BDNF, PI3K, AKT and CREB levels with depressive emotion and impulsive behaviors in drug-naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 23(1), 225 (2023).

Indrigo, M. et al. Nuclear ERK1/2 signaling potentiation enhances neuroprotection and cognition via Importinalpha1/KPNA2. EMBO Mol. Med. 15(11), e15984 (2023).

Zheng, L. et al. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential of icariin in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Phytomedicine 116, 154890 (2023).

Calderaro, A. et al. The neuroprotective potentiality of flavonoids on Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(23), 14835 (2022).

Jauhar, S., Johnstone, M. & McKenna, P. J. Schizophrenia. Lancet 399(10323), 473–486 (2022).

McCutcheon, R. A., Reis Marques, T. & Howes, O. D. Schizophrenia-An overview. JAMA Psychiatry 77(2), 201–210 (2020).

Hao, K. et al. Nicotinamide reverses deficits in puberty-born neurons and cognitive function after maternal separation. J. Neuroinflamm. 19(1), 232 (2022).

Roceri, M., Hendriks, W., Racagni, G., Ellenbroek, B. A. & Riva, M. A. Early maternal deprivation reduces the expression of BDNF and NMDA receptor subunits in rat hippocampus. Mol. Psychiatry 7(6), 609–616 (2002).

Chen, P., Chen, F., Lei, J. & Zhou, B. Gut microbial metabolite urolithin B attenuates intestinal immunity function in vivo in aging mice and in vitro in HT29 cells by regulating oxidative stress and inflammatory signalling. Food Funct. 12(23), 11938–11955 (2021).

Buenrostro-Jauregui, M. et al. Immunohistochemistry techniques to analyze cellular proliferation and neurogenesis in rats using the thymidine analog BrdU. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/61483-v (2020).

Malberg, J. E., Eisch, A. J., Nestler, E. J. & Duman, R. S. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 20(24), 9104–9110 (2000).

Yu, X. et al. Fingolimod ameliorates schizophrenia-like cognitive impairments induced by phencyclidine in male rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 180(2), 161–173 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31770381) and Wu Jieping Medical Foundation of China (No.320.6750.2023-25-6). We thank scidraw.io for the rat illustrations, adapted with permission.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Z., Ren, Z., Wang, S. et al. Urolithin A alleviates schizophrenic-like behaviors and cognitive impairment in rats through modulation of neuroinflammation, neurogenesis, and synaptic plasticity. Sci Rep 15, 10477 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93554-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93554-9