Abstract

This paper presents an analytical design method for the high-efficiency Class-EF\(_{n}\) power amplifier (PA). The proposed Class-EF power amplifier overcomes the practical limitation of the large inductance required in the load network and has a low normalized switch voltage of 2. The description of the two new lumped element and transmission line load networks have been presented. It is essential to mention that the proposed load networks simultaneously satisfy the impedance requirements at fundamental, second, third, fourth, and fifth harmonics. However, dc-to-RF efficiency is theoretically higher than the Class-EF with a lower harmonic control circuit. More importantly, adding one or more higher-order harmonic components can further improve the voltage or current waveforms. When more harmonic tuning is applied, more ripples are generated. To verify the validity of the proposed PA, two design examples, one with lumped elements and the other with transmission lines, have been designed. The measured results show a wide bandwidth from 1.9 to 2.9 GHz. Over this frequency range, drain efficiency is between 70-83%, with output power greater than 39.5 dBm and power gain larger than 10 dB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

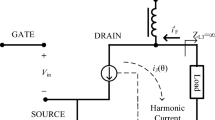

High-efficiency broadband power amplifiers (PAs) are critical for fifth-generation communication standards. Since heat dissipation from PAs affects transmitter performance, broadband PAs must deliver power while maintaining high efficiency through simple output matching networks. Energy efficiency is essential in modern wireless communication systems, as PAs are major energy consumers in mobile and fixed networks. Enhanced PA efficiency improves battery life in mobile devices, reduces operational costs in fixed systems, and supports sustainability by lowering energy consumption. However, non-constant envelope (non-CE) modulation techniques (e.g., QPSK, QAM, OFDM) in modern standards like Wi-Fi, LTE, and 5G trade energy efficiency for spectral efficiency, impacting transmitter performance. The proposed Class-EF PA aims to address these challenges by improving energy efficiency while maintaining performance across a broad bandwidth for next-generation communication systems. Harmonic control is a well-known technique for minimizing overlap and shaping drain current and voltage waveforms. Compared to low-pass filters (LPFs), which only filter higher-frequency components, the harmonic control method reduces overlap by shaping the waveforms to resemble ideal square pulses and half-sinusoidal waveforms, thereby reducing power loss and improving efficiency. Several kinds of high-efficiency PAs have been introduced, such as Class-D1,2,3,4, Class-E5,6,7, Class-F8,9, and Class-F\(^{-1}\)10. Due to the parasitic effects of the device, Class-D topologies have limitations at microwave frequencies. Class-E PA mode, due to its simplicity and high efficiency has been extensively utilized in designing and implementing PAs11. However, Class-E PA topologies have device speed limitations and high normalized switch voltages of 3.6. By matching at the fundamental and harmonic frequencies, in Class-F\(^{-1}\), the switch current and voltage waveforms are square and half-sinusoidal, respectively12. In13, The current-mode Class-DE power amplifier is designed to provide high efficiency and low voltage stress by achieving zero-current switching (ZCS) and zero current-derivative switching (ZCDS) conditions at the transistor’s turn-off instant. Soft switching techniques play a crucial role in reducing power dissipation in MOSFETs by minimizing the overlap between voltage and current during transitions. Unlike hard switching, where parasitic capacitance causes power loss due to voltage and current overlap during on/off states, soft switching methods like zero voltage switching (ZVS) and ZCS optimize transitions. ZVS adjusts voltage to avoid overlap, while ZCS slows current changes to achieve smoother operation and lower power loss. Gain curves at different frequencies, provided in the revised manuscript, validate the bandwidth choices and highlight the performance advantages of the proposed design. The novel Class-F/E power amplifiers using series and parallel output filters combined with third harmonic control circuits have been proposed in14,15. However, the Class-F/E PA with a series output filter has a lower maximum switch voltage and the capability to absorb the parasitic inductance compared to Class-F/E with a shunt filter. In16, a closed-form expression for the drain current of a continuous-mode inverse Class-GF power amplifier is introduced. In17, the performance of the parallel Class-E PA using the resonance network of a Class-F\(^{-1}\)PA has been improved. The high-efficiency continuous mode Class-F PA has been presented in18. The input impedance of the load network of the PA is optimized for stability and high power-added efficiency. High efficiency and wide bandwidth Class-EFJ PA combination of Class-EF (high efficiency) and Class-J (broadband) PAs has been proposed in19. The inverse Class-E PA, introduced in20, produces the ZCS and ZCDS conditions from ON-to-OFF transition. However, the practical efficiency can be decreased by power loss due to discontinuity in the switch voltage during the OFF-to-ON transition. To overcome the mentioned problems, the Class-E\(_{M}\)PA introduced in21, while the main circuit satisfies ZVS, ZVDS, ZCS, and ZCDS conditions and the auxiliary circuit satisfies the ZVS condition. The circuits reported in22,23 have two main drawbacks. Firstly, they employ ideal RF chokes (RFCs) with low self-resonant frequencies (SRFs) and high loss. In addition, the Class-E\(_{M}\) topologies has a high peak switch voltage of 4.3. So, a new topology, the so-called Class-E\(_{M}\)/F\(_{n}\)PA with soft-switching conditions, i.e., ZVS, ZVDS, ZCS, and ZCDS and narrow bandwidth, has been introduced in24. In25, an extended and generalized PC Class-E/F\(_{3}\) PA is proposed by adding a series reactive element to the load network and importing the initial phase shift of the third harmonic.

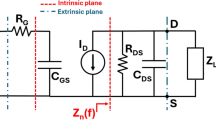

The variants of Class-EF PAs in26,27,28offer a low peak switch voltage as in Class-F and soft switching operation as Class-E. In26, the choke inductance in Class-E and Class-F has been replaced by a quarter-wavelength transmission line to facilitate the practical implementation at a higher frequency. In27, the lumped element Class-EF PA with the first three harmonics has been introduced. However, at the higher frequency, the lumped inductor and capacitor have capacitive and inductive characteristics, respectively. So, obtaining three harmonic frequency requirements, is the main challenge at microwave frequency. At high frequencies, the required optimum shunt capacitance for Class-EF is lower than the transistor shunt capacitance. Consequently, the power dissipation during the OFF-to-ON transition cannot be achieved at high frequencies because of a non-switching operation. Further, a major challenge in Class-EF PA design is that for a given output power and dc supply voltage, the maximum operating frequency is constrained by the transistor output capacitance. Therefore, an external shunt inductance can be used to cancel the excess capacitance at the fundamental frequency27. However, at higher harmonics, i.e., \(2f_0\), \(3f_0\), \(4f_0\), \(5f_0\), the reactance of the external shunt inductance and excess capacitance would be capacitive. As a consequence, the high impedance requirement at odd harmonics would be violated. In order to address the mentioned problem, we introduce two novel Class-EF PAs. The third harmonic Class-EF PA satisfies the open-circuit termination requirement at \(3f_0\), and the fifth harmonic Class-EF PA satisfies the open-circuit termination at \(3f_0\) and \(5f_0\). Moreover, the short-circuit termination at even harmonics is satisfied through a quarter-wavelength line at the drain node. These configurations permit the operation at higher frequencies at no expense to other PA figures of merit. We can mention the following design challenges and the corresponding contributions of the work as

-

1.

Addressing the excess capacitance issue in Class-EF amplifiers: In previous designs, only up to the third harmonic was considered due to the trade-off between performance and complexity. Controlling harmonics up to the third order provided a practical balance between efficiency and the number of components required. However, this approach left room for further improvement in efficiency. The decision to consider the fourth and fifth harmonics in this work aimed to achieve higher efficiency while minimizing the component count. By integrating the harmonic control network with the matching network, the proposed method reduces the total number of elements, enhancing performance without significantly increasing design complexity. This innovation enables efficient control of higher-order harmonics, improving power amplifier performance. Shaping voltage and current waveforms to resemble ideal square pulses and half-sine waves minimizes overlap, reducing power dissipation and boosting efficiency. This approach overcomes the limitations of conventional methods while striking a balance between increased design complexity and enhanced performance.

-

2.

Reducing the size and electrical series resistance of the total series inductance: Conventional Class-EF amplifiers26,27,28 often require a large total series inductance, which is accompanied by a high electrical series resistance. This resistance is comparable to the optimum load resistance, leading to a degradation of overall efficiency. Additionally, large inductors have limited applications at high frequencies due to their low self-resonant frequency. The proposed structure addresses this challenge by replacing the large series inductor with two resonant circuits consisting of low-value inductors.

The paper is organized as follows. The lumped element and transmission line load network to realize high frequency implementation of Class-EF PA are introduced in Section II. To verify the analytical approach, a broadband PA was fabricated and measured in Section III. Finally, the conclusion is presented in Section IV.

Theoretical analysis of Class-EF PA using fifth-order harmonics

Load-pull

To obtain the fundamental load impedance in Class-EF, a load pull test for the 10 W Cree GaN model at the operating frequency of 2.5 GHz has been done. Therefore, the output plane and power-added efficiency (PAE) contours at the packaged devices are computed and shown in Fig. 1(a), and Fig. 1(b), respectively. Table 1 presents the optimal load impedance for various cases, along with the corresponding output power and power added efficiency (PAE) values. The Table helps to highlight the achieved high PAE and output power, with specific emphasis on the case where the load impedance is \(Z_L=11.84+j12.8\). Next, keeping the optimal impedance \(Z_L\), the output matching network consisting of \(L=1.52nH\), \(C_0=2.7pF\), \(C=4.07pF\) has been designed. Then, the series inductor L has been divided into \(L_{A}\) and \(L_{B}\) as shown in Fig. 2(b) to provide the required optimum impedance at the fundamental and harmonic frequencies.

Synthesis of the lumped-element matching network

The output matching network in this paper is designed to transfer a 50\(\Omega\) to an optimum impedance and have two, third, fourth, and fifth harmonic control circuits, for maximum efficiency, and suppress the harmonics. The proposed network not only provides the optimum inductor and capacitor at fundamental frequencies, but also provides the short circuit at 5 and 10 GHz, and open circuit condition at 7.5 and 12.5 GHz. The LC network in Fig. 2(b) is chosen to synthesize the required inductor and capacitor values at the fundamental and harmonic frequencies. Therefore, the \(L_A\) and \(L_B\) have been replaced with Networks 1 and 2 in Fig. 3.

Network 1, consisting of \(L_0\), \(L_1\), and \(C_1\), is used to synthesize the inductor \(L_A\) at \(f_0\) and provide an open circuit at 3\(f_0\) and short circuit at 5\(f_0\). Network 2, comprising \(L_2\) and \(C_2\), is used to synthesize the inductor \(L_B\) at \(f_0\) and provide an open circuit at 5\(f_0\). Network 3, consisting of \(L_3\) (\(L_4\)) and \(C_3\) (\(C_4\)), is used to synthesize the capacitor C at \(f_0\) and provide short circuits at 3\(f_0\) and 5\(f_0\). The flowchart in Fig. 4 provides an overview of the design procedures and the sequence of steps involved in designing the power amplifier.

The harmonic control network is designed using equations (1) to (17) to match the fundamental frequency while controlling harmonics up to the fifth order, eliminating the need for a separate matching network and simplifying the system. The central frequency is selected for optimal matching, ensuring improved PA efficiency and reduced distortion.

The impedance of the Network 1 is obtained as

where

and

at \(\omega =\omega _0=2\pi \times 2.5\times 10^9,\) we have

Making use of the Network 1 impedance condition in (1)-(4), results in the following equations as

Solving (5) and (6) results in

Network 2 consisting of \(L_2\) and \(C_2\) is used to synthesize the inductor \(L_B= 0.52 nH\) at \(f_0\), and an open circuit at \(5f_0\). The impedance of the Network 2 is obtained as

where

at \(\omega =\omega _0=2\pi \times 2.5\times 10^9\), we have

Network 3 consisting of \(L_3\), \(C_3\), \(L_4\), and \(C_4\) is used to synthesize the capacitor \(C=4.07pF\) at \(f_0\) and short circuit at \(3f_0\), and \(5f_0\). The impedance of the Network 3 is obtained as

where

Making use of the Network 3 impedance condition in (10) at \(\omega =\omega _0=2\pi \times 2.5\times 10^9\), (11), and (12), the following equations have been obtained

Solving (16) and (17) and using (13) and (14) results in

In power amplifier designs with harmonic control, adding more networks at the output to tune higher-order harmonics can indeed increase the number of components, leading to potential losses in the output matching network. To minimize these losses, the proposed design integrates the harmonic control network into the output matching network itself. By doing so, it eliminates the need for extra components, reducing losses. The design, as shown in Fig. 3, achieves proper harmonic control and matching with fewer elements, effectively meeting the desired harmonic conditions without adding unnecessary complexity or losses. The load impedances at the fundamental and harmonic frequencies are plotted in Fig. 5. As can be seen, the Class-EF mode requirements at harmonic frequencies are met concurrently, as the optimal impedance at the fundamental frequency. Also, the simulated impedances of the designed lumped element output matching network considering a tolerance of \(\pm 5\%\) are shown in Fig. 5. This figure demonstrates that the proposed multi-matching network is capable of maintaining acceptable impedance characteristics even with component tolerances. Therefore, the suggested network is robust enough to counter the tolerance of \(\pm 5\%\). The third and fifth harmonic lumped element Class-EF PAs are shown in Fig. 6. The steady-state voltage and current waveforms of the third and fifth harmonic Class-EF are illustrated in Fig. 7. As can be observed, the ZVS and ZVDS conditions are satisfied during the OFF-to-ON transition. Further, consistent with the theory, the maximally flat peak switch voltage (Vsw) of \(2V_{DC}=56V\) is obtained.The simulated results for both the third and fifth harmonics, using an ideal switch to compare the impact of controlling up to the third versus the fifth harmonic. As the number of controlled harmonics increases, the voltage and current waveforms approach ideal square pulse and half-sine wave shapes, which significantly reduces overlap and power loss, thereby enhancing efficiency. The key comparison here is between harmonic control up to the third order (Fig. 7a) and the fifth order (Fig. 7b). The waveforms in Fig. 7b are closer to the ideal shapes, showcasing a notable improvement in efficiency. This reduction in waveform overlap leads to lower power dissipation and higher efficiency. In the simulation, the drain efficiency for the PA controlling up to the third harmonic reaches 98%, while for the fifth harmonic, it increases to 99%. This improvement highlights the effectiveness of controlling higher-order harmonics, which results in more efficient operation and less energy wasted, compared to the traditional approach of only considering the third harmonic. The simulated output power spectrum of the Class-EF PA with third and fifth harmonic control circuit is shown in Fig. 8.

Synthesis of the transmission line load network

In this section, transmission lines are employed (equations 18 to 25) to enhance performance by minimizing parasitic effects and ensuring impedance matching. The transmission line load network, based on the aforementioned fundamental frequency matching approaches and harmonic tuning, has been designed. In Fig. 9, the lines \(T_{o1}\), \(T_{o2}\), and \(S_{o2}\) represent sections of transmission lines and stubs that are utilized to provide impedance matching and performance similar to the lumped elements in Fig. 6(b). By carefully designing the load network, it is possible to achieve the desired impedance matching and circuit behavior. However, the lines in Fig. 9 do not have an equal number of elements compared to the nine lumped elements in the Fig. 6(b). To have compact and broadband load network with low insertion loss, the quarter-wavelength \(\lambda /4\) TL at the drain terminal in Fig. 6(b) has been replaced by a subquarter wavelength TL, hence the load network in Fig. 9 is proposed. Therefore, we introduce one topology providing two series TLs, including \(T_{o1}\) and \(T_{o2}\), and two shunt stubs, including \(S_{o1}\), and \(S_{o2}\). First, the free design parameters \(\theta _{S1}\), and \(\theta _{S2}\), are chosen as \(30^{\circ }\). The short-circuit stub \(S_{o1}\) and the open-circuit stub \(S_{o2}\) with an electrical length of \(30^{\circ }\) present a short-circuit and open-circuit node and the optimum impedance at the third harmonic includes \(T_{o1}\), and \(T_{o2}\). Therefore, the third harmonic impedance, \(Z_{OMN}\)(\(3f_0\)), can be written as

where

At the fundamental, second, fourth, and fifth harmonic frequencies, the optimum impedance includes \(T_{o1}\), \(T_{o2},\) \(S_{o1}\), \(S_{o1}\), and \(S_{o2}\). Therefore, the harmonic impedances, \(Z_{OMN}\)(\(nf_0\)) are obtained as

where \(Z_{A1}\) is

and \(Z_{A2}\) and \(Z_{A3}\) are

Finally, \(Z_{A4}\) is obtained as

where \(Z_{A5}\) is

Supposing that \(S_{o1}\) and \(S_{o2}\) have the same characteristic impedance, the electrical characteristics of \(T_{o1}\), \(T_{o2}\), \(S_{o1}\), and \(S_{o2}\) are calculated to match \(Z_{OMN}\) in (18) and (20) at the package plane using the load-pull approach. The aforementioned fundamental frequency and harmonic tuning approaches are used to design the output matching network.

In summary, the load network at the third harmonic includes \(T_{o1}\) and \(T_{o2}\), which provides open circuit condition at \(3f_0\) similar to \(L_0\), \(L_1\), \(C_1\), \(L_3\), and \(C_3\) in Fig. 6(b). At the fundamental, second, fourth, and fifth harmonic frequencies, the optimum impedance includes \(T_{o1}\), \(T_{o2}\), \(S_{o1}\), and \(S_{o2}\) which provides open circuit condition at \(5f_0\) and desired impedance at \(f_0\), \(2f_0\), \(3f_0\), \(4f_0\) similar to Fig. 6(b). However, the role of the parallel-and series resonators in Fig. 6(b) to provide desired impedance at different frequencies are taken over by \(T_{o1}\), \(T_{o2}\), \(S_{o1}\), and \(S_{o2}\). Finally, the obtained impedances at the package and intrinsic-drain plane are shown in Fig. 10. As can be observed, the fundamental and harmonic impedance requirements are located near the design space for harmonic frequencies.

Design input matching network

The optimal lowpass input matching network can be obtained based on the implemented output matching network in the previous section. It clarifies that the design procedure for the input matching network is the same as the output matching network and is not repeated in that section. The parameters of the final circuit are shown in Fig. 11.

Simulation and experimental results

The complete circuit schematic, simulation and experimental results of the PA will be presented in this section. According to the analysis given previously, a broadband PA on the Rogers substrate RO4003C is designed and implemented by connecting the input and output matching networks to the transistor. A Cree CGH40010F GaN HEMT packaged device. The bias point of the transistor is a Class AB bias point. The gate and drain voltage of the transistor are specified as −2.2 V, and 28V, respectively. It is worth noting that the specific biasing scheme and values may vary depending on the design requirements and application of the amplifier. The final schematic and photograph of the fabricated power amplifier are shown in Fig. 11 and 12, respectively. Large-signal continuous wave (CW) measurements for power and efficiency characterization were conducted using a National Instruments (NI) PXIe-5646R Vector Signal Transceiver (VST). The VST supports a carrier frequency range of up to 6 GHz and features high-speed digital I/O capabilities of up to 250 Mbit/s. This instrument generated both CW signals within the specified frequency range. The input signal was first amplified using a 10 W driving amplifier before being fed into the device under test (DUT). The output of the PA was then routed through an attenuator to protect the VST during signal analysis. This setup ensured precise power and efficiency characterization, while the VST’s capabilities allowed for accurate linearity testing under modulated signal conditions.

The dynamic characteristics of the fabricated PA has been evaluated with different input power levels. Fig. 13(a)-(c) show the efficiency, PAE, output power, and gain versus input power level at 1.9, 2.2, and 2.8 GHz, respectively. In Fig. 13(a)-(c), the selection of frequencies refers to the operating frequencies of the power amplifier at different points within the passband. These waveforms provide insights into the behavior and performance of the power amplifier at different frequencies within its operational range. It can be seen that at 2.2 GHz, the best results of PAE of 76.3%, efficiency of 83% and output power of 40 dBm have been obtained. Also, the simulated output power spectrum is shown in Fig. 14.

Fig. 15 shows the simulated and measured efficiency, PAE, output power, and gain over the entire frequency band. It can be observed that at the operating frequency band from 1.9 to 2.9 GHz, the measured efficiency is from 70% to 83%, which corresponds to a relative bandwidth of 40%. At this frequency range, PAE varies between 60.7% and 76.3% and gain higher than 10 dB is obtained. Over the same frequency range, the output power is 39.5 to 40.4 dBm. Fig. 16 shows the simulated and measured output spectrum at 2.5 GHz with a 12 MHz frequency offset and an average input power of 25 dBm. The adjacent channel power ratio (ACPR) is −39 dBc, indicating that the power amplifier demonstrates relatively good linearity performance at the 1 dB gain compression point. This result highlights the trade-off between efficiency and linearity, demonstrating that while the PA achieves high efficiency, it maintains a good level of linearity, making it suitable for practical communication systems. A comparison between the proposed PA and the narrow and wideband PAs are summarized in Table 2. First,Within the operating frequency band, the proposed PA achieves a high drain efficiency of 70% to 83%, surpassing broadband amplifiers [9], [11], and [19] at higher frequencies, with performance comparable to other references. Notably, the high-frequency weighted efficiency (FE) of 95.1% exceeds all other references, except [15], which is a narrowband PA. These results underscore the proposed PA’s competitive edge in both broadband and high-frequency performance.

Conclusion

This paper proposed a comprehensive analysis of Class-EF PA, utilizing a closed-form expression for the control of harmonics up to the fifth order. Unlike the conventional lumped element Class-EF approach, which primarily focuses on the second and third harmonics, the proposed method extends harmonic impedance control to the fifth order, thereby expanding the design space for fundamental output matching impedance and improving PA efficiency. The integration of the harmonic control circuit up to the fifth order with the output matching network at the fundamental frequency achieves several objectives, including suppressing unwanted harmonic components to ensure compliance with regulatory standards, minimizing interference with neighboring frequency bands, and simplifying the design. This combined approach reduces the overall size, cost, and complexity of the power amplifier system. Measured results demonstrated a drain efficiency exceeding 70% across 1.9 to 2.9 GHz, a gain between 10 and 10.2 dB with a gain flatness of 0.2 dB, and output power ranging from 39.5 to 40.4 dBm. A significant challenge addressed in this work was deriving an equivalent circuit using transmission lines, as parallel LC circuits lack direct transmission-line equivalents. To address this, a novel circuit design with similar functionality was introduced. Future work could explore transforming parallel LC circuits into transmission-line-based equivalents with comparable performance, utilizing advanced materials to enhance efficiency, broadening adaptability to wider frequency ranges, and investigating environmental factors such as temperature to improve reliability under real-world conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

References

Wang, X., Zhao, Z., Li, K., Chen, K. & Liu, F. Analysis of the Steady-State Current Ripple in Multileg Class-D Power Amplifiers Under Inductance Mismatches. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 34, 3646–3657 (2019).

Luo, W., Yin, Y., Xiong, L., Li, T. & Xu, H. Nonlinear Analytical Model for Switched-Capacitor Class-D RF Power Amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, Reg. Papers 66, 2309–2321 (2019).

Yang, S.-H. et al. A Low-THD Class-D Audio Amplifier With Dual-Level Dual-Phase Carrier Pulsewidth Modulation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 62, 7181–7190 (2015).

Chierchie, F., Paolini, E. E., Stefanazzi, L. & Oliva, A. R. Simple Real-Time Digital PWM Implementation for Class-D Amplifiers With Distortion-Free Baseband. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 61, 5472–5479 (2014).

Surakitbovorn, K. N. & Rivas-Davila, J. M. On the Optimization of a Class-E Power Amplifier With GaN HEMTs at Megahertz Operation. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 35, 4009–4023 (2020).

Hayati, M., Roshani, S., Roshani, S., Kazimierczuk, M. K. & Sekiya, H. Design of Class E Power Amplifier with New Structure and Flat Top Switch Voltage Waveform. IEEE Trans. Power Electron 33, 2571–2579 (2018).

Hayati, M., Lotfi, A., Kazimierczuk, M. K. & Sekiya, H. Generalized Design Considerations and Analysis of Class-E Amplifier for Sinusoidal and Square Input Voltage Waveforms. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 62, 211–220 (2015).

Liu, C. Analysis of Class-F Power Amplifiers With a Second-Harmonic Input Voltage Manipulation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst., II, Exp. Briefs 67, 225–229 (2020).

Zheng, S. Y., Liu, Z. W., Zhang, X. Y., Zhou, X. Y. & Chan, W. S. Design of Ultrawideband High-Efficiency Extended Continuous Class-F Power Amplifier. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 65, 4661–4669 (2018).

Sharma, T. et al. Simplified First-Pass Design of High-Efficiency Class-F\(^{-1}\) Power Amplifiers Based on Second-Harmonic Minima. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 67, 3147–3161 (2019).

You, F. & Benedikt, J. An Optimized-Load-Impedance Calculation and Mining Method Based on I-V Curves Using Broadband Class-E Power Amplifier as Example. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 66, 5254–5263 (2019).

Ekhteraei, M., Hayati, M. & Shama, F. High-Efficiency Low Voltage Inverse Class-F Power Amplifier Design Based on Harmonic Control Network Analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, Reg. Papers 67, 806–814 (2020).

Sheikhi, A., Abdipour, A., Grebennikov, A. & Hemesi, H. Effect of Shunt Capacitances on Performance of Current-Mode Class-DE Power Amplifier at Any Active Time. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 33, 7038–7045 (2018).

Sheikhi, A., Hayati, M. & Grebennikov, A. High-Efficiency Class-E\(^{-1}\) and Class-F/E Power Amplifiers at Any Duty Ratio. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron 63, 840–848 (2016).

Sheikhi, A. & Hemesi, H. Analysis and Design of the Novel Class-F/E Power Amplifier With Series Output Filter. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst., II, Exp. Briefs 69, 779–783 (2022).

Eskandari, S., Zhao, Y., Helaoui, M., Ghannouchi, F. M. & Kouki, A. B. Continuous-Mode Inverse Class-GF Power Amplifier With Second-Harmonic Impedance Optimization at Device Input. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 69, 2506–2518 (2021).

Liu, C. & Cheng, Q.-F. Analysis and Design of High-Efficiency Parallel-Circuit Class-E/F Power Amplifier. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 67, 2382–2392 (2019).

Zarghami, S., Hayati, M., Kazimierczuk, M. K. & Sekiya, H. Continuous Class-F Power Amplifier Using Quasi-Elliptic Low-Pass Filtering Matching Network. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst., II, Exp. Briefs 67, 2407–2411 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Cheng, Z., Ke, H., Liu, G. & Li, S. Design of a Broadband High-Efficiency Hybrid Class-EFJ Power Amplifier. IEEE Microw. Wireless Compon. Lett 30, 407–409 (2020).

Mury, T. & Fusco, V. F. Series-L/parallel-tuned comparison with shunt-C/series-tuned class-E power amplifier. IEE Proc. Circuits, Devices Syst 152, 709–717 (2005).

A. Telegdy, B. M. & Sokal, N. O. Class-E\(_{M}\) switching-mode tuned powe amplifier-high efficiency with-switching transisitor. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 51, 1662–1676 (2003).

R. Miyahara, H. & Kazimierczuk, M. Design of Class-E\(_{M}\) power amplifier taking into account auxiliary circuit. in Proc. 34th Annu. Conf. IEEE Ind. Electron 679–684 (2008).

R. Miyahara, H. & Kazimierczuk, M. K. Extended Continuous Inverse Class-F Power Amplifiers With Class-AB Bias Conditions. IEEE Microw. Wireless Compon. Lett 27, 368–370 (2017).

Safari Mugisho, M., Thian, M., Piacibello, A., Camarchia, V. & Quay, R. Harmonic-Injection Class-E\(_{M}\)/F\(_{n}\) Power Amplifier With Finite DC-Feed Inductance and Isolation Circuit. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 69, 3319–3334 (2021).

Yang, Z. et al. A Generalized High-Efficiency Broadband Class-E/F\(_{3}\) Power Amplifier Based on Design Space Expanding of Load Network. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 68, 3732–3744 (2020).

Grebennikov, A. High-Efficiency Class-FE Tuned Power Amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst., I: Reqular Papers 55, 3284–3292 (2008).

Thian, M. & Fusco, V. Analysis and Design of Class-E\(_{3}\)F and Transmission-Line Class-E\(_{3}\)F\(_{2}\) Power Amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst., I: Reqular Papers 58, 902–912 (2011).

Thian, M., Barakat, A. & Fusco, V. High-Efficiency Harmonic-Peaking Class-EF Power Amplifiers With Enhanced Maximum Operating Frequency. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 63, 659–651 (2015).

Chen, K. & Peroulis, D. Design of Broadband Highly Efficient Harmonic-Tuned Power Amplifier Using In-Band Continuous Class-F\(^{-1}\)/F Mode Transferring. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 60, 4107–4116 (2012).

Meng, X., Yu, C., Liu, Y. & Wu, Y. Design Approach for Implementation of Class-J Broadband Power Amplifiers Using Synthesized Band-Pass and Low-Pass Matching Topology. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn 65, 4984–4996 (2017).

Aghajani, S., Kamarei, M. & Chegini, M. Aeu-international journal of electronics and communications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst., I: Reqular Papers 174, 155038 (2011).

Xuan, X. et al. Design a wideband high-efficiency continuous class-gf power amplifier based on a source second harmonic manipulation architecture. Microwave and Optical Technology Letters 66, 34081 (2024).

Bai, G. et al. Design of broadband doherty power amplifier based on single loop load modulation network. IEEE Journal on Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems 14, 122–132 (2024).

Cai, Q., Liang, Y., Gao, Z., Quan, X. & Che, W. A wideband power amplifier based on filtering matching for both input and output network. Microwave and Optical Technology Letters 77, 34270 (2024).

Zaid, M., Pampori, A., Nazir, M. & Chauhan, Y. Gan-based wide-band high-efficiency power amplifier with multi harmonic resonance. Microelectronics Journal 145, 106129 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sepahvand, E., Sheikhi, A. Analysis and design of the novel five harmonic peaking Class-EF power amplifier. Sci Rep 15, 9890 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93556-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93556-7