Abstract

Multimodal medical image fusion (MMIF) integrates complementary information from different imaging modalities to enhance image quality and remove redundant data, benefiting a variety of clinical applications such as tumor detection and organ delineation. However, existing MMIF methods often struggle to preserve sharp edges and maintain high contrast, both of which are critical for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning. To address these limitations, this paper proposes ECFusion, a novel MMIF framework that explicitly incorporates edge prior information and leverages a cross-scale transformer. First, an Edge-Augmented Module (EAM) employs the Sobel operator to extract edge features, thereby improving the representation and preservation of edge details. Second, a Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion Module (CSTF) with a Hierarchical Cross-Scale Embedding Layer (HCEL) captures multi-scale contextual information and enhances the global consistency of fused images. Additionally, a multi-path fusion strategy is introduced to disentangle deep and shallow features, mitigating feature loss during fusion. We conduct extensive experiments on the AANLIB dataset, evaluating CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI fusion tasks. Compared with state-of-the-art methods (U2Fusion, EMFusion, SwinFusion, and CDDFuse), ECFusion produces fused images with clearer edges and higher contrast. Quantitative results further highlight improvements in mutual information (MI), structural similarity (Qabf, SSIM), and visual perception (VIF, Qcb, Qcv).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

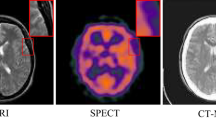

Accurate and comprehensive medical imaging plays a crucial role in modern clinical practice. While individual imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET) each provide valuable structural or functional information, no single modality captures the full complexity of many diseases1. For example, CT excels at depicting dense tissues such as bone and implants, whereas MRI offers excellent soft-tissue contrast for inflammation or lesions2. Functional modalities like SPECT and PET visualize metabolic activities but have lower spatial resolution. Consequently, relying on a single modality may limit the ability to make precise diagnoses or to formulate optimal treatment plans, particularly in tumor detection and surgical navigation3.

Multimodal medical image fusion (MMIF) integrates complementary information from multiple imaging modalities into a single image, supporting more informed clinical decisions4. By combining anatomical details (for example, from CT or MRI) with functional data (from PET or SPECT), clinicians obtain a broader view of a pathology’s location, extent, and metabolic activity5. However, implementing MMIF remains challenging. First, differences in resolution, contrast, and noise across modalities can introduce registration errors and artifacts. Second, subtle yet critical anatomical boundaries may appear blurred if the fusion method fails to preserve edge information6. Third, retaining contrast in low-intensity or lesion-detailed regions is essential for accurate diagnosis and monitoring7.

Early MMIF techniques generally employed rule-driven or decomposition-based fusion strategies such as wavelet transforms, pyramid decompositions, or sparse coding8,9,10,11. Although these methods have shown success in integrating multi-scale information, they rely heavily on handcrafted features and pre-defined fusion rules, limiting their adaptability to various modality combinations or pathological conditions. Misalignment in frequency or spatial domains can also cause artifacts or reduced contrast in the fused results. More recent advances in deep learning have led to convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that learn data-driven feature representations, reducing the need for manual feature engineering12. Nevertheless, CNN-based methods often struggle with long-range dependencies or multi-scale contextual details, resulting in pixel misalignment and information loss in complex fusion scenarios13.

Attention mechanisms, particularly Transformers, have been explored by several researchers to address these challenges, given their ability to capture long-distance relationships13,14,15,16,17,18. Yet, many existing Transformer-based fusion approaches rely on fixed patch sizes or simplistic attention configurations, limiting their capacity to capture both global context and localized features. Meanwhile, edge-preserving strategies in deep learning are frequently restricted to post-processing or straightforward concatenation of edge maps, which may introduce noise or artifacts19,20. Moreover, suboptimal choices in network architecture or loss functions can cause artifacts such as pixel shifts or reduced contrast. As shown in Figure 1, some methods in PET-MRI fusion exhibit pixel deviations in background regions (red box) and MRI-only regions (green box), compromising overall contrast. Methods like TIMFusion and MUFusion also lose edge texture, especially in brain folds.

Pixel shift problem in PET-MRI fusion. Shown are the input PET image, MRI image, and each method’s fusion result. The upper right enlargement displays the binary difference image between the red area in each fusion result and the corresponding PET image; the lower right enlargement shows the binary difference image between the green area and the corresponding MRI image.

These shortcomings highlight the need for a strategy that explicitly enhances edge details and models multi-scale information within a unified framework. To address these issues, this paper proposes ECFusion, an unsupervised deep learning framework that integrates edge enhancement with cross-scale Transformer fusion. The method focuses on preserving anatomical boundaries, reducing pixel shifts, and maintaining contrast in complex clinical scenarios.

In summary, the key contributions of this work are:

-

1.

An Edge-Augmented Module (EAM) that utilizes Sobel-based prior edge information for improved boundary preservation during feature extraction.

-

2.

A Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion Module (CSTF) designed to capture multi-scale global context, enabling better coordination of structural and functional information.

-

3.

A multi-path strategy to disentangle shallow and deep features, mitigating information loss and improving fusion stability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant MMIF and edge-preserving methods. Section 3 details the ECFusion architecture, including the EAM and CSTF modules, and introduces the loss functions used for unsupervised training. Section 4 discusses experimental evaluations, including comparisons with state-of-the-art fusion approaches. Section 5 addresses potential threats to validity, and Section 6 concludes the paper with suggested directions for future research.

Related works

In recent years, deep learning-based multimodal medical image fusion (MMIF) methods have attracted significant interest, owing to their ability to learn hierarchical features. This section examines related work from two primary perspectives: (i) fusion approaches based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and (ii) Transformer-based methods. Finally, existing strategies for preserving edge details in fusion tasks are discussed.

CNN-based MMIF methods

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have proven effective in image fusion due to their capacity for hierarchical feature extraction via stacked convolutional layers. Early studies, such as Liu et al.21, minimized the need for handcrafted features by learning mapping functions directly from source images to weight maps. Subsequently, Zhang et al.12 proposed IFCNN, an end-to-end framework that integrates feature extraction, fusion, and reconstruction. These methods demonstrated CNNs’ ability to capture important local features.

To further enrich fused representations, Xu et al.22 introduced EMFusion, which employs a pre-trained encoder to retain modality-specific information from CT, PET, or SPECT images. Similarly, Cheng et al.23 proposed MUFusion, which adaptively blends source images and intermediate fusion outputs to balance their contributions. Despite these advances, CNN-based methods may still struggle with long-range dependencies and global context modeling, which can cause blur or edge loss when merging diverse modalities.

Transformer-based MMIF methods

Transformers excel at capturing global context through multi-head self-attention, a mechanism originally popularized in natural language processing (NLP). Vision Transformer (ViT) 24 and its variants 25,26,27 have been widely applied to diverse vision tasks, including object detection 28,29, semantic segmentation 30,31, image generation 32, and multi-modal learning 33,34. In MMIF, researchers have explored replacing convolutional operations with attention-based modules to enhance global feature interaction 13,14,15,16,17,18. However, effectively merging high-level contextual information with fine-grained details remains an open challenge for many transformer-based methods, largely due to fixed patch sizes or limited attention scopes 35,36,37,38,39,40.

Edge preservation in image fusion

Preserving edge details is critical in medical imaging, where subtle boundary information can significantly influence clinical decision-making. Traditional approaches often employ edge-preserving filters (for example, bilateral, guided, or Gaussian curvature filters41,42,43,44) combined with activity-level measurements to guide the fusion process. Although effective, these methods typically require complex handcrafted designs and may introduce artifacts or halos near edges.

Recent deep learning-based methods also examine edge information. Zhu et al.19 extracted edges from an initial fused image in multi-exposure settings, while Wei et al.20 concatenated Sobel-based edge maps in the decoder. Although these strategies can enhance detail fidelity, direct concatenation or naive weighting may introduce noise. Similarly, Ma et al.45 proposed an edge-focused adversarial loss, but improper weighting can degrade contrast in non-edge regions.

In our approach, Sobel-based edge maps are incorporated before feature extraction to guide CNNs, ensuring that edge features are highlighted in both spatial and channel dimensions. A cross-scale Transformer module is further integrated to maintain global coherence. By addressing edges at an early stage and modeling multi-scale context through attention, the proposed method seeks to preserve fine details without sacrificing global contrast in the fused images.

Proposed method

This section provides a detailed description of our proposed ECFusion method. We first present the overall network architecture, followed by a comprehensive explanation of each module and the associated loss function.

ECFusion framework

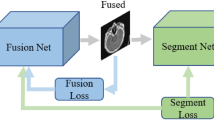

The overall architecture of ECFusion is illustrated in Figure 2. It consists of three main modules: an Edge-Augmented Module (EAM), a Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion Module (CSTF), and an image reconstruction module (Decoder). These modules are responsible for multi-level feature extraction, feature fusion, and image reconstruction, respectively.

For simplicity, we assume that the input images \(I_a\) and \(I_b\) are single-channel grayscale images. The fusion process begins by feeding \(I_a\) and \(I_b\) into their respective EAM modules to extract multi-level features, denoted as \(FI_{a}^{1,2,3}\) and \(FI_{b}^{1,2,3}\). Subsequently, features at the same level (e.g., \(FI_{a}^{i}\) and \(FI_{b}^{i}\)) are sent to their corresponding CSTF modules for fusion. The fused outputs are then concatenated along the channel dimension and passed to the Decoder to generate the final fused image \(I_f\).

Edge-augmented module (EAM)

Preserving edge and texture details is essential in medical image fusion, as these details often correspond to critical anatomical structures (e.g., brain folds in MRI images and boundaries between normal and diseased tissues in SPECT or PET images). Such structures are vital for accurate clinical diagnosis. To address potential edge blurring in fused images, we integrate an edge detection component into our proposed ECFusion framework.

The EAM comprises two main components: an Edge module and a Feature Extraction module. The Edge module extracts an edge map from the input image, which serves as an auxiliary input to the Feature Extraction module. The Feature Extraction module includes a channel expansion head, which increases the number of input image channels to \(C_{\text {edge}}\), followed by eight residual blocks.

Edge Module The Edge module employs two Sobel operators, \(G_x\) and \(G_y\), as convolution kernels to capture horizontal and vertical edge information from the input image \(I\). The resulting edge map \(I_{\text {edge}}\) is computed as:

where \(\circledast\) denotes the convolution operation.

Feature Enhancement (FE) Module Within each residual block of the Feature Extraction module, the edge map \(I_{\text {edge}}\) is processed by a Feature Enhancement (FE) module, illustrated in Figure 3. This module is inspired by the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) 46, which applies spatial and channel attention. However, unlike CBAM, our FE module accepts two inputs—the incoming feature map \(F_{\text {in}}\) and an additional edge feature map \(F_{\text {edge}}\)—thus leveraging boundary information to enhance features along both spatial and channel dimensions.

To prevent optimization difficulties caused by directly integrating the raw edge map, the FE module first applies a convolutional layer and a LeakyReLU activation to \(I_{\text {edge}}\), producing an edge feature map \(F_{\text {edge}}\) with \(C_{\text {edge}}\) channels:

Next, global max pooling (\(\text {GMP}\)) and global average pooling (\(\text {GAP}\)) are applied to \(F_{\text {edge}}\) and processed by an MLP:

where the MLP weight matrices \(W_0 \in \mathbb {R}^{\frac{C}{r} \times C}\) and \(W_1 \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times \frac{C}{r}}\) reduce the channel dimension by a factor of \(r\), set to 2 in our experiments. Here, \(C\) denotes the number of input channels, and \(\text {GELU}\) is the Gaussian Error Linear Unit activation function.

We then combine the spatially enhanced and channel-enhanced features to obtain the final output:

where \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication. By incorporating \(F_{\text {edge}}\) as an auxiliary input, the FE module is able to highlight boundary information more effectively than a standard CBAM-based approach.

We extract intermediate outputs from the 2nd, 4th, and 8th residual blocks to obtain multi-level features \(FI_{a}^{1,2,3}\) and \(FI_{b}^{1,2,3}\) for subsequent fusion. This multi-path fusion strategy separates the fusion of deep and shallow features by routing multiple outputs from the encoder into distinct paths. Through path integration, features from different paths are aggregated to ensure that both low-level details and high-level contextual information are effectively captured. As shown in Figure 4, this strategy enables the network to perform more robust fusion by integrating features from multiple pathways, each focusing on different aspects of the image. This approach not only preserves fine-grained details but also maintains global context, resulting in improved fusion performance across multiple tasks.

Cross-scale transformer fusion module (CSTF)

While multi-scale information is crucial for enhancing the visual quality of fused images, Vision Transformer (ViT) models typically divide the input image into fixed-size patches that are then linearly embedded to form a sequence of tokens. This process often relies on convolution operations with a fixed window size, potentially limiting the model’s ability to capture contextual information at multiple scales. Although employing multiple kernels of different sizes can mitigate this issue, such strategies often lead to significantly increased parameter counts and computational complexity.

To enable efficient cross-scale modeling without a large parameter overhead, we propose a Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion Module (CSTF). By introducing a novel Hierarchical Cross-Scale Embedding Layer (HCEL), our approach allows tokens to capture contextual information at multiple scales while maintaining a reasonable number of parameters.

Overall Module Structure Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the CSTF module. After obtaining the multi-level features \(FI_{a}^{1,2,3}\) and \(FI_{b}^{1,2,3}\) from the Edge-Augmented Module (EAM), features at the same level (denoted as \(FI_a^{i}\) and \(FI_b^{i}\)) are fed into the CSTF as inputs \(X\) and \(Y\), respectively.

Taking the \(X\) branch as an example, the following subsection details how the HCEL generates multi-scale tokens, which the cross-scale Transformer mechanism then uses to fuse the complementary information from the two branches.

Hierarchical Cross-Scale Embedding Layer (HCEL) Let the input feature map be denoted by \(X = fea_0 \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times C \times H \times W}\), where \(B\) is the batch size, \(C\) is the number of channels, and \(H, W\) are the spatial dimensions. We define the number of embedded tokens \(N\) as:

where \(P\) is the patch size.

The HCEL progressively converts the multi-resolution features \((fea_0, fea_1, \ldots , fea_n)\) into a set of tokens \((\text {token}_0, \text {token}_1, \ldots , \text {token}_n)\). These tokens capture multi-scale contextual information, ultimately producing query, key, and value embeddings \((Q, K, V)\) for subsequent transformer operations.

Formally, the core operations of the HCEL are expressed by:

where:

-

\(TK_i(\cdot )\) denotes the convolution-based tokenization of \(fea_i\), with kernel size \(k = P\) and stride \(s = \tfrac{P}{2^i}\). This produces \(\text {token}_i \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times N \times C_i}\) (see Algorithm 1, line 3).

-

\(DS_i(\cdot )\) applies a \(3 \times 3\) convolution with stride 2 to downsample \(fea_i\), yielding \(fea_{i+1}\) (Algorithm 1, line 5).

-

\(Q, K \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times N \times \sum _{i=0}^{n} C_i}\) and \(V \in \mathbb {R}^{B \times N \times C_0}\) serve as the final query, key, and value embeddings, respectively (Algorithm 1, lines 7–8).

By downsampling and tokenizing features \((fea_0 \rightarrow fea_1 \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow fea_n)\), the HCEL effectively captures multi-scale representations across various resolutions. This strategy enhances global context modeling and expands the network’s representational capacity.

Figure 5 illustrates how these steps integrate to encode multi-scale contextual information. As the original feature map is downsampled and transformed by successively larger strides, each \(\text {token}_i\) captures a progressively broader receptive field. Concatenating these tokens along the channel dimension thus combines both local details and long-range context, ultimately contributing to more robust feature representations and, by extension, improved fusion performance.

Cross-Scale Attention and Feedforward Network After the HCEL process, we obtain \([Q_x, K_x, V_x]\) and \([Q_y, K_y, V_y]\) for the \(X\) and \(Y\) branches, respectively. We then perform cross-attention and feedforward network (FFN) operations as follows.

For the \(X\) branch:

For the \(Y\) branch:

The attention mechanism is calculated as:

where \(p\) is the learnable relative position encoding and \(d\) is the dimension of the output vector.

Finally, \(T_x\) and \(T_y\) are upsampled from \(\mathbb {R}^{B \times C \times N}\) to \(\mathbb {R}^{B \times C \times H \times W}\) via a resampling operation (\(\text {Re}\)). The results are then combined with the original inputs \(X\) and \(Y\) through element-wise multiplication, producing:

The final output, \(Out\), is obtained by merging the updated \(X\) and \(Y\) using a combination function, which in our case includes element-wise maximum, minimum, and addition operations to capture different facets of the input information:

Loss function

The loss function plays a crucial role in guiding the optimization process and ensuring the quality of the fused image. Our loss function consists of two components: a perceptual loss and a gradient loss. The overall fusion loss function, denoted as \(L_{fusion}\), is expressed as:

where \(L_{per}\) encourages feature similarity between the fused image and the input images, \(L_{gradient}\) promotes consistency in texture structure, and \(\lambda\) is a hyperparameter that balances the contribution of the perceptual loss.

The perceptual loss, \(L_{per}\), is calculated as:

where \(\phi _x^i\) denotes the feature map extracted from the \(i\)-th layer of a VGG19 network pre-trained on the ImageNet1K dataset.

To enhance the fusion of texture details, the gradient loss, \(L_{gradient}\), encourages the gradient of the fused image to approximate the maximum gradient of the two source images. This is calculated as:

where \(\nabla\) denotes the gradient operator and \(\left\| \cdot \right\| _2\) represents the L2 norm.

Experiment

In this section, we first describe the experimental setup in detail, and then present the visualization and objective results. Finally, ablation studies and an in-depth analysis are provided.

Experimental setup

Datasets and tasks

We evaluate our proposed ECFusion method on three multimodal medical image fusion tasks-CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI-using the Harvard medical image dataset.47 This dataset contains both normal and abnormal brain images across multiple imaging modalities (MRI, CT, PET, and SPECT). It provides labeled 3D anatomical scans in transaxial, sagittal, and coronal planes for normal brains, as well as various pathologies (e.g., cerebral toxoplasmosis, hemorrhage, stroke). Owing to its diverse modalities and clinical conditions, this dataset is well-suited for multimodal medical image fusion research.

For PET and SPECT images originally in RGB format, we convert each image to the Y-CbCr color space. The luminance channel (Y) is fused with the corresponding MRI image via ECFusion; afterward, the fused luminance channel is recombined with the chrominance channels (CbCr) and transformed back to RGB.

Data preprocessing

To form the training sets, we curate \(160\), \(245\), and \(333\) pairs of \(256 \times 256\)-pixel images for CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI, respectively. Each source image is then divided into \(9\) overlapping patches of size \(128 \times 128\), with a stride of \(64\) pixels. To increase dataset diversity and improve generalization, each patch has a \(50\%\) chance of being randomly masked by a \(64 \times 64\) white or black square. All patches are then upsampled to \(256 \times 256\) via nearest-neighbor interpolation and normalized to the range \([-1, 1]\). This procedure yields \(1440\), \(2205\), and \(2997\) pairs of training patches for CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI, respectively. For testing, \(24\) image pairs are selected per fusion task.

Implementation details

All experiments are implemented in the PyTorch framework and executed on an NVIDIA RTX 5000 Ada GPU. Each model is trained for \(50\) epochs using the Adam optimizer with a batch size of \(4\) and a learning rate of \(1 \times 10^{-3}\).

Hyperparameters

Our proposed Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion (CSTF) module is configured with \(n = 3\) embedding layers. In Eq. (5), the patch size \(P\) is set to 16. For Eq. (6), the channel dimensions \(\{C_i\}\) are assigned as \(\{32, 8, 8, 8\}\) for \(i = 0, 1, 2, 3\), respectively. Finally, the loss function in Eq. (14) includes a hyperparameter \(\lambda\), which is fixed at 0.02 throughout our experiments.

Comparative methods and evaluation metrics

We compare ECFusion against several state-of-the-art methods, including U2Fusion 48, EMFusion 22, SwinFusion 13, DeFusion 49, MuFusion 23, TIMFusion 50, and CDDFuse 18. Notably, SwinFusion 13 and CDDFuse 18 integrate transformer-based architectures, making them particularly relevant baselines for evaluating our method. Quantitative performance is assessed using mutual information (MI) 51, Qabf 52, visual information fidelity (VIF) 53, SSIM 54, Qcb 55, and Qcv 56.

Experimental results

CT and MRI image fusion

Figure 6 presents the qualitative fusion results for four representative image pairs. For U2Fusion and MuFusion, the pixel values in the black background regions deviate, showing an increase in intensity. The fused images produced by U2Fusion, EMFusion, DeFusion, MuFusion, and CDDFuse exhibit a significant reduction in the salient structural information from the CT images. In contrast, our method effectively avoids pixel value deviations, preserving both the salient information of dense bone structures from the CT image and the bone edge information from the MRI image, while also achieving better contrast.

As shown in the first row of Figure 6, our method successfully preserves the texture information of the brain folds from the MRI image in non-dense regions. In dense regions, it retains both the edge information and density from the CT image and the corresponding texture from the MRI image. This observation is further corroborated by the results in the second and third rows. In contrast, other methods tend to either completely discard or fail to effectively preserve the texture information from the MRI.

Figure 7 and Table 1 present the quantitative evaluation results. Our method achieves the best performance in terms of MI, Qabf, VIF, Qcb, and Qcv while achieving a slightly lower SSIM score. This may be because SSIM focuses on the overall similarity to the input images, while our method aims to comprehensively integrate salient information from both images, which may result in a lower similarity score to any single source image.

The proposed method is quantitatively compared with seven state-of-the-art methods on the CT-MRI fusion task. The x-axis represents the different fusion metrics, and the y-axis represents the corresponding metric values. White circles indicate the mean values, and black line segments indicate the median values. The metrics have been scaled for ease of visualization.

PET and MRI image fusion

This figure illustrates the typical fusion results of each method on the three tasks. The red box in the lower right corner highlights the binary difference image between the fused result and the CT/PET/SPECT image, which facilitates the visualization of the consistency of the fusion results across different methods in both background and salient regions.

The proposed method is quantitatively compared with seven state-of-the-art methods on the PET-MRI fusion task. The x-axis represents the different fusion metrics, and the y-axis represents the corresponding metric values. White circles indicate the mean values, and black line segments indicate the median values. The metrics have been scaled for ease of visualization.

Figure 8 shows the qualitative results on three representative test images. Our method demonstrates clear advantages in preserving information, avoiding background interference, and producing fused images with clear textures. The fusion results show that SwinFusion exhibits an upward deviation of pixel values in the background regions, while EMFusion, DeFusion, TIMFusion, and CDDFuse show a downward deviation in the foreground dense regions. These pixel value deviations can lead to reduced contrast and degraded image quality in the fused images. U2Fusion and MuFusion exhibit both upward and downward deviations of pixel values in the fused images, potentially weakening or distorting critical image information. This deviation issue is further visualized in the second row of Figure 9. In contrast, our method does not exhibit such deviations, perfectly preserving the salient information and texture details of the original images, thus achieving ideal fusion results.

Furthermore, our method excels at preserving the clear texture information of brain folds, as particularly evident in the first and third rows of Figure 8. In the second row, our method not only retains rich texture information but also surpasses other methods in preserving the saliency of bone structures. This demonstrates the clear advantages of our method in preserving details and fusing information. Due to the lower resolution of PET images compared to MRI images, some methods, such as MuFusion and CDDFuse, exhibit a mosaic effect, indicating their limitations in handling images with different resolutions. Our method successfully avoids the mosaic effect, ensuring the overall quality and visual consistency of the fused images.

As shown in Figure 10 and Table 2, our method achieves the best performance across all metrics: MI, Qabf, VIF, SSIM, Qcb, and Qcv. It particularly excels in metrics based on human visual perception, such as VIF, Qcb, and Qcv, indicating that our method produces fused images with superior perceptual quality. The optimal performance in MI, Qabf, and SSIM further demonstrates the effectiveness of our method in preserving edge and feature information.

SPECT and MRI image fusion

Figure 11 presents the qualitative comparison results of SPECT and MRI image fusion. The first and second rows demonstrate that our method avoids the masking of texture information in the MRI images by the color information of the SPECT images, resulting in clear texture structures. The third row shows that the SPECT image contains some noise (purple spots). In the fused results, both our method and EMFusion successfully suppress this noise, likely due to the deep-level constraints employed in both methods, which enhance their perceptual capabilities. Similar to the PET-MRI fusion results, our method, as shown in Figure 9, avoids pixel value deviations and maintains pixel consistency with the ideal fusion scenario in both the common background and unique information regions.

The quantitative results are shown in Figure 12 and Table 3. As the SPECT-MRI fusion task is similar to the PET-MRI fusion task, the analysis of the qualitative results aligns with that of the PET-MRI fusion. Our method demonstrates significant advantages in metrics such as MI, Qabf, VIF, and Qcv, indicating its superior performance in preserving texture and feature information and achieving high perceptual quality in the fused images. Although our method achieves slightly lower SSIM scores compared to CDDFuse, this is likely attributed to its inherent noise-filtering effect.

The proposed method is quantitatively compared with seven state-of-the-art methods on the SPECT-MRI fusion task. The x-axis represents the different fusion metrics, and the y-axis represents the corresponding metric values. White circles indicate the mean values, and black line segments indicate the median values. The metrics have been scaled for ease of visualization.

Ablation study

Feature enhancement module

In medical image fusion, texture and edge information are often more crucial than other details. These areas, such as the folds of the cerebral cortex and the boundaries between normal and diseased tissues, are characterized by significant pixel value variations. However, these regions may not necessarily have high pixel intensity, making them susceptible to information loss during neural network processing.

To mitigate this loss, we extract edge pixels as prior knowledge and utilize them as auxiliary input to the feature extraction module. This strategy aims to enhance the intermediate representation of edge information. To evaluate its effectiveness, we conduct an ablation study by removing the feature enhancement module from our proposed EAM.

As shown in Table 4, incorporating the FE module leads to an improvement in Qabf, VIF, SSIM, Qcb, and Qcv metrics.

Multi-scale fusion module

Vision Transformers (ViT) utilize position encoding to provide tokens with spatial information, enabling them to understand their location within the input sequence. In our approach, we introduce a Hierarchical Convolutional Embedding Layer (HCEL) to generate intermediate tokens at multiple scales. These multi-scale tokens are then concatenated along the channel dimension, producing tokens with enhanced context awareness.

The HCEL achieves multi-scale representation by maintaining a constant convolution kernel size while halving the stride during the downsampling and convolutional embedding process. This effectively doubles the receptive field of each subsequent token, allowing it to capture information from a larger spatial context. By integrating information from various scales, the tokens gain a more comprehensive understanding of the input image.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of this multi-scale strategy, we performed an ablation study. We modified the HCEL to halve both the convolution kernel size and the stride after downsampling, preventing the expansion of the receptive field. This modification effectively removes the multi-scale characteristic, resulting in tokens that lack context-awareness. The performance degradation observed in this ablation study confirms the importance of cross-scale modeling for achieving effective medical image fusion.

The quantitative results in Table 4 demonstrate that our multi-scale strategy consistently improves performance across all three fusion tasks (CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI), as evidenced by the increased MI, Qabf, VIF, Qcb, and Qcv metrics.

Multiple paths

To enhance information preservation and fusion robustness, we decouple the fusion process of shallow and deep features. This decoupling allows for more effective preservation of detailed information by extracting multi-level feature representations of a single image and introducing distinct fusion paths for features at the same level. This strategy also enables the propagation of shallow features to the subsequent decoding module.

Qualitative comparison of multi-path fusion strategy on CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI image pairs. Rows from top to bottom represent CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI results, respectively. Columns show the source images (CT/PET/SPECT and MRI), fusion results without and with the multi-path strategy, and their corresponding difference images with the source images.

To evaluate the effectiveness of this multi-path strategy, we conducted an ablation study where only the final deep features were extracted and fused through a single path. As shown in Table 4, removing the multi-path strategy resulted in lower MI, Qabf, VIF, SSIM, and Qcv metrics, indicating its significant advantages in information preservation and fusion quality.

Qualitative results are presented in Figure 13. The difference images between the fused image and the source images demonstrates that the multi-path strategy enhances the preservation of background information and unique features. This is particularly evident in the PET-MRI fusion results, where the background of the fused image closely aligns with the MRI image.

Hyperparameter analysis

Perceptual loss weight

To encourage feature-level similarity in the fused image, we incorporate a perceptual loss weighted by \(\lambda\). Table 5 shows that a small \(\lambda\) (e.g., 0.02) provides a noticeable improvement in MI, Qabf, VIF, and Qcb metrics compared to not using any perceptual loss (\(\lambda = 0\)). However, excessively large \(\lambda\) values (e.g., \(\lambda = 0.2\)) can destabilize training and compromise certain modality-specific features. As depicted in Figure 14, when \(\lambda = 0.2\), the model fails to preserve critical MRI details in the CT-MRI fusion task. Based on these observations, \(\lambda = 0.02\) strikes the best balance, mitigating instability while improving key fusion metrics.

Number of fusion paths

The multi-path fusion strategy enhances the robustness of image fusion by aggregating features from multiple paths, as illustrated in Figure 15. For an input image \(I_a\) , each fusion path generates different fused feature maps ( \(FI_1\), \(FI_2\), \(FI_3\) ), capturing distinct aspects of the image. These feature maps are then aggregated to produce the final fused feature map ( \(FI_f\) ), which is input to the decoder to generate the fused image. Thus, the number of fusion paths is a critical hyperparameter in the model.

However, increasing the number of paths beyond an optimal point can introduce redundant information, leading to a rise in model parameters and computational cost without a corresponding improvement in fusion quality. As shown in Table 6, when the number of paths is increased from 3 to 4, the performance metrics, including mutual information (MI) and Qabf, actually decline in CT-MRI fusion tasks. This result aligns with our analysis, suggesting that excessive paths introduce unnecessary complexity without further enhancing fusion performance.

Computational complexity analysis

In addition to visual and quantitative assessments of fusion quality, we analyze the computational cost and resource usage of our proposed method alongside several state-of-the-art approaches (SwinFusion, DeFusion, MuFusion, TIMFusion, and CDDFuse). All methods, including our own, were implemented using the PyTorch framework for consistency and fairness in comparisons. Table 7 reports four key metrics: the total number of trainable parameters (Params), the floating-point operations (GFLOPs), the maximum GPU memory usage (Max Mem), and the average inference time (Inf. Time).

As shown in Table 7, our proposed method achieves a balanced trade-off between model size, computational complexity, and speed. Although MuFusion has the fewest parameters (0.55 M) and TIMFusion attains the lowest FLOPs (8.4 GFLOPs) and fastest inference time (7.4 ms), our approach still maintains a compact architecture (0.92 M params), moderate FLOPs (14.56 GFLOPs), and relatively low memory usage (0.6 GB), while running at 13.4 ms per image. Compared with methods such as SwinFusion or DeFusion, the proposed approach is significantly more efficient in memory footprint and inference speed. This efficiency is particularly advantageous in real-time or resource-constrained clinical settings, where large-scale image data must be processed rapidly.

Threats to validity

In this section, we discuss potential threats to the validity of the proposed ECFusion framework. While the method demonstrates significant improvements over current techniques, acknowledging these areas helps provide a clearer understanding of its scope and future development opportunities.

Internal validity

Internal validity focuses on factors within the experimental setup that may influence the results:

Dataset Characteristics: The evaluation was conducted using the AANLIB dataset, which provides a diverse range of high-quality medical images. Although this dataset is comprehensive, it may not fully represent all clinical scenarios or imaging conditions found in real-world clinical practice. Expanding the evaluation to larger, more diverse datasets will further ensure the robustness of ECFusion across various clinical settings, providing a more accurate reflection of its performance in broader healthcare environments.

Model Sensitivity to Hyperparameters: The performance of ECFusion is influenced by the selection of hyperparameters, particularly the weight (\(\lambda\)) used in the perceptual loss function. While strong results have been achieved with the current settings, ECFusion has the flexibility to be adapted to various clinical applications. Refining the hyperparameters through further optimization will enhance its versatility, ensuring it performs optimally across a wide range of imaging tasks.

Edge Detection Integration: The Edge-Augmented Module (EAM) utilizes the Sobel operator for edge enhancement, which works effectively for high-quality images. In certain scenarios with low contrast or significant noise, edge detection may need refinement. To improve the accuracy of edge preservation in such conditions, alternative edge-detection methods will be explored, ensuring ECFusion performs optimally across diverse imaging environments.

External validity

External validity considers the generalizability of the results to real-world clinical settings and other imaging modalities:

Generalizability to Other Modalities: The evaluation focused on fusion tasks involving CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI. ECFusion has shown strong potential for generalization, and validating its performance across additional imaging modalities, such as ultrasound57 and X-ray58, will provide insights into its versatility. This will further demonstrate the framework’s adaptability to a wide range of imaging types and clinical scenarios.

Clinical Applicability: The experiments were conducted using high-performance computational resources and a relatively small dataset. For clinical use, real-time processing and handling of large-scale datasets are essential. Our computational efficiency experiments (Table 7) show that, although ECFusion exhibits competitive performance, its inference speed lags slightly behind that of TIMFusion. Optimizing ECFusion for real-time clinical applications will increase its relevance for fast, accurate image fusion in clinical environments. Techniques such as model pruning and hardware-specific optimizations will ensure scalability and efficiency, making the framework more practical for everyday clinical use.

Construct validity

Construct validity refers to whether the method effectively measures what it intends to measure and whether the chosen metrics accurately reflect the quality of the fused images:

Evaluation Metrics: The performance of ECFusion was assessed using widely accepted metrics, including mutual information (MI), SSIM, and VIF. While these metrics are valuable, incorporating expert clinical feedback will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the clinical value of the fused images, ensuring that the method aligns with the practical needs of medical professionals.

Perceptual Loss Function: The perceptual loss function used in this study has shown promising results for preserving important structural and textural details. To improve its adaptability across various imaging tasks, future work will explore alternative perceptual loss functions to strike the best balance between structural preservation and contrast enhancement, enhancing the framework’s versatility.

Conclusion validity

The ECFusion framework demonstrates strong performance in multimodal medical image fusion, achieving significant improvements over existing methods. While certain areas, such as dataset expansion, real-time optimization, and adaptation to additional imaging modalities, provide opportunities for further enhancement, the framework has already shown considerable potential. Ongoing efforts will refine and optimize ECFusion, ensuring its robustness and applicability across a variety of clinical settings. These improvements will further solidify its value as a powerful tool in medical image processing.

Conclusions and future work

This paper presented ECFusion, a medical image fusion framework that combines edge enhancement and a cross-scale Transformer. An edge-enhancement feature extraction module was designed to leverage Sobel-based edge maps as auxiliary input, thereby enriching the representation of edge information. By incorporating a multi-path fusion strategy, the proposed approach separates the fusion processes of deep and shallow features, mitigating information loss and improving fusion stability. In addition, the Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion Module (CSTF) employs a Hierarchical Cross-scale Embedding Layer (HCEL) to introduce multi-scale characteristics, enhancing the visual quality of fused images.

A perceptual loss function was used to achieve feature-level similarity. Experimental results on CT-MRI, PET-MRI, and SPECT-MRI tasks demonstrated that ECFusion produces clear textures and preserves contrast, while avoiding pixel-value deviations observed in other methods. Notably, the framework achieves competitive performance on metrics such as SSIM, despite not explicitly incorporating SSIM constraints.

Although the current method utilizes Sobel-based edge maps, future work will explore more flexible and robust edge extraction strategies. In addition, evaluating ECFusion on larger and more diverse datasets will further assess its scalability and applicability in real-time clinical scenarios. Finally, optimizing the framework for large-scale, time-sensitive tasks can help establish ECFusion as a valuable tool in medical image processing.

Data availability

The data is publicly available at http://www.med.harvard.edu/AANLIB/home.html.

References

Zhou, T. et al. Deep learning methods for medical image fusion: A review. Computers in Biology and Medicine 160, 106959 (2023).

Azam, M. A. et al. A review on multimodal medical image fusion: Compendious analysis of medical modalities, multimodal databases, fusion techniques and quality metrics. Computers in biology and medicine 144, 105253 (2022).

Wong, K. C., Kumta, S. M., Antonio, G. E. & Tse, L. F. Image fusion for computer-assisted bone tumor surgery. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 466, 2533–2541 (2008).

James, A. P. & Dasarathy, B. V. Medical image fusion: A survey of the state of the art. Information fusion 19, 4–19 (2014).

Karim, S. et al. Current advances and future perspectives of image fusion: A comprehensive review. Information Fusion 90, 185–217 (2023).

Li, J., Liu, J., Zhou, S., Zhang, Q. & Kasabov, N. K. Gesenet: A general semantic-guided network with couple mask ensemble for medical image fusion. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems (2023).

Dinh, P.-H. Medical image fusion based on enhanced three-layer image decomposition and chameleon swarm algorithm. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 84, 104740 (2023).

Chao, Z. et al. Medical image fusion via discrete stationary wavelet transform and an enhanced radial basis function neural network. Applied Soft Computing 118, 108542 (2022).

Wang, Z., Cui, Z. & Zhu, Y. Multi-modal medical image fusion by laplacian pyramid and adaptive sparse representation. Computers in Biology and Medicine 123, 103823 (2020).

Zhang, Q., Liu, Y., Blum, R. S., Han, J. & Tao, D. Sparse representation based multi-sensor image fusion for multi-focus and multi-modality images: A review. Information Fusion 40, 57–75 (2018).

Zhu, Z., Yin, H., Chai, Y., Li, Y. & Qi, G. A novel multi-modality image fusion method based on image decomposition and sparse representation. Information Sciences 432, 516–529 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ifcnn: A general image fusion framework based on convolutional neural network. Information Fusion 54, 99–118 (2020).

Ma, J. et al. Swinfusion: Cross-domain long-range learning for general image fusion via swin transformer. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 9, 1200–1217 (2022).

Li, H. & Wu, X.-J. Crossfuse: A novel cross attention mechanism based infrared and visible image fusion approach. Information Fusion 103, 102147 (2024).

Qu, L., Liu, S., Wang, M. & Song, Z. Transmef: A transformer-based multi-exposure image fusion framework using self-supervised multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 36, 2126–2134 (2022).

Wang, Z., Chen, Y., Shao, W., Li, H. & Zhang, L. Swinfuse: A residual swin transformer fusion network for infrared and visible images. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 71, 1–12 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Transformer-based end-to-end anatomical and functional image fusion. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 71, 1–11 (2022).

Zhao, Z. et al. Cddfuse: Correlation-driven dual-branch feature decomposition for multi-modality image fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 5906–5916 (2023).

Zhu, M., Pan, P., Chen, W. & Yang, Y. Eemefn: Low-light image enhancement via edge-enhanced multi-exposure fusion network. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 34, 13106–13113 (2020).

Xue, W., Wang, A. & Zhao, L. Flfuse-net: A fast and lightweight infrared and visible image fusion network via feature flow and edge compensation for salient information. Infrared Physics & Technology 127, 104383 (2022).

Liu, Y., Chen, X., Cheng, J. & Peng, H. A medical image fusion method based on convolutional neural networks. In 2017 20th international conference on information fusion (Fusion), 1–7 (IEEE, 2017).

Xu, H. & Ma, J. Emfusion: An unsupervised enhanced medical image fusion network. Information Fusion 76, 177–186 (2021).

Cheng, C., Xu, T. & Wu, X.-J. Mufusion: A general unsupervised image fusion network based on memory unit. Information Fusion 92, 80–92 (2023).

Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Khan, S. et al. Transformers in vision: A survey. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 54, 1–41 (2022).

Han, K. et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 45, 87–110 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. A survey of visual transformers. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems (2023).

Carion, N. et al. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In European conference on computer vision, 213–229 (Springer, 2020).

Fang, Y. et al. You only look at one sequence: Rethinking transformer in vision through object detection. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34, 26183–26197 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.04306 (2021).

Xiong, X. et al. Sam2-unet: Segment anything 2 makes strong encoder for natural and medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08870 (2024).

Jiang, Y., Chang, S. & Wang, Z. Transgan: Two pure transformers can make one strong gan, and that can scale up. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34, 14745–14758 (2021).

Antol, S. et al. Vqa: Visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2425–2433 (2015).

Radford, A. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International conference on machine learning, 8748–8763 (PMLR, 2021).

Dong, X. et al. Cswin transformer: A general vision transformer backbone with cross-shaped windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 12124–12134 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 10012–10022 (2021).

Tu, Z. et al. Maxvit: Multi-axis vision transformer. In European conference on computer vision, 459–479 (Springer, 2022).

Huang, Z. et al. Ccnet: Criss-cross attention for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 603–612 (2019).

Zhu, L., Wang, X., Ke, Z., Zhang, W. & Lau, R. W. Biformer: Vision transformer with bi-level routing attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 10323–10333 (2023).

Xia, Z., Pan, X., Song, S., Li, L. E. & Huang, G. Vision transformer with deformable attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 4794–4803 (2022).

Li, X., Zhou, F., Tan, H., Zhang, W. & Zhao, C. Multimodal medical image fusion based on joint bilateral filter and local gradient energy. Information Sciences 569, 302–325 (2021).

Hu, J. & Li, S. The multiscale directional bilateral filter and its application to multisensor image fusion. Information Fusion 13, 196–206 (2012).

Li, S., Kang, X. & Hu, J. Image fusion with guided filtering. IEEE Transactions on Image processing 22, 2864–2875 (2013).

Jiang, Q. et al. Medical image fusion using a new entropy measure between intuitionistic fuzzy sets joint gaussian curvature filter. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 7, 494–508 (2023).

Ma, J. et al. Infrared and visible image fusion via detail preserving adversarial learning. Information Fusion 54, 85–98 (2020).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J.-Y. & Kweon, I. S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 3–19 (2018).

Keith A. Johnson, J. A. B. Whole brain atlas. http://www.med.harvard.edu/AANLIB/home.html.

Xu, H., Ma, J., Jiang, J., Guo, X. & Ling, H. U2fusion: A unified unsupervised image fusion network. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 44, 502–518 (2020).

Liang, P., Jiang, J., Liu, X. & Ma, J. Fusion from decomposition: A self-supervised decomposition approach for image fusion. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 719–735 (Springer, 2022).

Liu, R., Liu, Z., Liu, J., Fan, X. & Luo, Z. A task-guided, implicitly-searched and metainitialized deep model for image fusion. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2024).

Qu, G., Zhang, D. & Yan, P. Information measure for performance of image fusion. Electronics letters 38, 1 (2002).

Xydeas, C. S. et al. Objective image fusion performance measure. Electronics letters 36, 308–309 (2000).

Han, Y., Cai, Y., Cao, Y. & Xu, X. A new image fusion performance metric based on visual information fidelity. Information fusion 14, 127–135 (2013).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE transactions on image processing 13, 600–612 (2004).

Chen, Y. & Blum, R. S. A new automated quality assessment algorithm for image fusion. Image and vision computing 27, 1421–1432 (2009).

Chen, H. & Varshney, P. K. A human perception inspired quality metric for image fusion based on regional information. Information fusion 8, 193–207 (2007).

Valerio, M. et al. Detection of clinically significant prostate cancer using magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion targeted biopsy: a systematic review. European urology 68, 8–19 (2015).

Guida, C., Zhang, M. & Shan, J. Improving knee osteoarthritis classification using multimodal intermediate fusion of x-ray, mri, and clinical information. Neural Computing and Applications 35, 9763–9772 (2023).

Funding

The work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai Municipality (22ZR1416500).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Daoqi Wu wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Weichao Ding prepared Figures 2, 3. Fei Luo conducted the review, revisions, and supervision. Luis Rojas Pino revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, F., Wu, D., Pino, L.R. et al. A novel multimodel medical image fusion framework with edge enhancement and cross-scale transformer. Sci Rep 15, 11657 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93616-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93616-y