Abstract

Acute myocarditis, characterized by inflammatory myocardial injury, significantly risks heart failure and sudden death. Despite its severity, specific biomarkers are lacking. This study applied metabolomic analysis to urine samples from 21 acute myocarditis patients and 21 controls using UPLC-MS/MS, revealing 728 increased and 820 decreased metabolites in patients. The affected pathways were predominantly related to the amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, and others. We have validated 19 metabolites with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) greater than 0.7 and a high level of identification confidence. Potential biomarkers upregulated in acute myocarditis patients included phytosphingosine, N-acetylneuraminic acid, indolelactic acid, L-glutamic acid, 4-pyridoxic acid, N1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide, palmitic acid, hydroxyphenyllactic acid, riboflavin, nicotinic acid, choline, N-formylkynurenine, guanine, and hypoxanthine. Conversely, sebacic acid, 4-vinylphenol sulfate, capryloylglycine, 4-ethylphenylsulfate, and azelaic acid were found to be decreased. Collectively, the metabolomic profiling has uncovered distinct metabolic signatures in patients with acute myocarditis. The amino acid metabolism appears to play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of acute myocarditis, offering potential avenues for diagnostic and therapeutic development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myocarditis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the heart muscle, which can spontaneously progress to dilated cardiomyopathy and, in severe cases, may even lead to sudden cardiac death. The global prevalence of myocarditis is estimated to be between 4 to 14 cases per 100,000 individuals, with a mortality rate ranging from 1 to 7%1. Notably, children and young adults are more susceptible to acute myocarditis than their middle-aged and older counterparts2, and intriguingly, males exhibit a slightly higher incidence rate than females3. Acute myocarditis is primarily triggered by viral infections, but it can also result from bacterial, protozoal, or fungal infections, as well as from exposure to various toxic substances, medications, and systemic immune-mediated disorders4. Given the complex clinical presentations and the wide range of etiological factors associated with acute myocarditis, it is imperative to delve deeper into the understanding of its pathological mechanisms and to identify potential biomarkers for improved diagnosis and treatment.

Metabolomics provides a distinct advantage by offering a comprehensive snapshot of the metabolic status in cardiac diseases5. Several studies leveraging metabolomics in acute myocarditis research have utilized Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) rodent models. For instance, NMR-based metabolomic analysis revealed disruptions in metabolic pathways within cardiac tissues and serum of mice with acute myocarditis induced by CVB3. These disruptions included pathways such as nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, and D-glutamine and D-glutamate metabolism6,7. Additionally, another study employed ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) metabolomics to investigate the cardiac metabolic profile disturbances in CVB3-induced acute viral myocarditis in mice, uncovering a positive correlation between estrone 3-sulfate and desoxycortone with the disturbed gut microbiome8. While the clinical scenario is considerably more intricate than what animal models can represent. To date, there appears to be a scarcity of research that has specifically examined the metabolite profiles in patients with acute myocarditis.

In this pioneering cross-sectional study, we enrolled 21 patients with acute myocarditis and 21 healthy controls to analyze their metabolic profiles using UPLC-MS/MS. This represents the first application of a non-targeted metabolomics approach in this context, aiming to identify potential biomarkers and elucidate related metabolic pathways in acute myocarditis patients.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study is a cross-sectional investigation that was granted approval by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan City People’s Hospital and was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki. The study population comprised individuals diagnosed with acute myocarditis at the Department of Cardiology, Zhongshan People’s Hospital, Zhongshan, China, between October 2022 and December 2023. Eligibility for the study required a clinical diagnosis of acute myocarditis and the absence of coronary artery lesions as determined by coronary angiography or coronary CTA. The diagnosis of acute myocarditis was based on the criteria set forth by the Circulation Journal9. Participant information was meticulously recorded, including details such as age, sex, weight, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), troponin T (TnT), creatine kinase isoenzyme MB (CK-MB), and various other pertinent clinical indicators. A control group of healthy individuals, matched for age and sex, was also enrolled. Each participant provided written informed consent. Fasting morning urine samples (10 mL) were collected from volunteers using sterile urine cups. For patients diagnosed with acute myocarditis, urine samples were obtained within 48 h of diagnosis. The samples were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 15 min and then stored at − 80 °C for subsequent analysis.

Sample preparation

Before analysis, all urine samples, including quality control (QC) samples, were prepared using the established method10. A volume of 100 µL from each urine sample was extracted by adding 700 µL of precooled solvent mixture (methanol: acetonitrile: water, 4:2:1, v/v/v). The methanol (A454-4) and acetonitrile (A998-4), both LC–MS grade, were sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA. Following 1 min of vortexing and a 2-h incubation at -20 °C, the samples were centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C using an Eppendorf Low Speed Cryogenic Universal Centrifuge (Model 5430). The supernatant was then transferred to a fresh split EP tube and evaporated using a vacuum concentrator. The residue was reconstituted in 180 µL of methanol: pure water (1:1, v/v), vortexed for 10 min, and centrifuged again at 25,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The clear supernatant was transferred to a sample vial for UPLC-MS/MS analysis. To mitigate the influence of injection order on the results, the sequence of clinical sample injections was randomized. Additionally, QC samples, which are pooled aliquots from all the samples analyzed, were processed every five samples to evaluate the consistency and stability of the UPLC-MS/MS system throughout the entire acquisition process.

Untargeted UPLC-MS/MS analysis

In this study, metabolite separation and detection were achieved using a Waters 2777c UPLC (Waters, USA) coupled with a Q Exactive HF high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The chromatographic separation was conducted on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters, USA), with the column temperature regulated at 45 °C. The mobile phase in positive mode comprised 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in methanol (B), while in negative mode, it was composed of 10 mM ammonium formate in water (A) and 95% methanol containing 10 mM ammonium formate (B). Ammonium formate (17,843-250G) was sourced from Honeywell Fluka in the USA, and formic acid (50,144-50 mL) was obtained from DIMKA in the USA. The gradient elution program was as follows: 0–1 min, 2% B; 1–9 min, linear gradient to 98% B; 9–12 min, held at 98% B; 12–12.1 min, a return to 2% B; and 12.1–15 min, re-equilibration at 2% B. The flow rate was set at 0.35 mL/min, and the injection volume was 5 μL. The Q Exactive HF was utilized for both primary and secondary stages of mass spectrometry data acquisition. The mass spectrometry parameters for both positive and negative ionization modes were configured as follows: spray voltage, 3.8 kV for positive and − 3.2 kV for negative; sheath gas flow rate, 40; auxiliary gas flow rate, 10; auxiliary gas heater temperature, 350 °C; and capillary temperature, 320 °C.

Data preprocessing

Offline mass spectrometry data were imported into Compound Discoverer 3.3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, https://mycompounddiscoverer.com/) software for analysis in conjunction with the BGI Metabolome Database (BMDB, https://biosys.bgi.com/), mzCloud database (https://www.mzcloud.org/), and ChemSpider online database (https://www.chemspider.com/). This process yielded a data matrix containing metabolite peak area and identification results, which were subsequently subjected to further analysis and processing.

The data were imported into MetaX for comprehensive preprocessing and subsequent statistical analysis, following established protocols11. This approach ensured a robust framework for data normalization, transformation, and the application of advanced statistical techniques to uncover meaningful biological insights. In the preprocessing phase, data were meticulously normalized to correct for any technical variability and to facilitate direct comparisons across samples. Normalize the data to obtain relative peak areas by probabilistic quotient normalization (PQN). Quality control-based robust LOESS signal correction (QC-RLSC) was applied to address batch effects and to eliminate metabolites exhibiting a coefficient of variation (CV) exceeding 30% in the QC samples.

Multivariate analysis for metabolite identification

Log transformation and Pareto scaling were integral to the implementation of principal component analysis (PCA), ensuring an accurate depiction of the intrinsic distribution of the samples. After log2 transformation, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and its orthogonal variant (OPLS-DA) models were constructed between the comparative groups, using Pareto scaling, and were validated using a sevenfold cross-validation during model development. The variable importance in the projection (VIP), fold change (FC), and q-value were crucial in identifying differential metabolites.

Selection of potential biomarkers

In metabolomic studies, biomarker selection is generally based on statistical significance (q-value), differential expression (Fold Change), model importance (VIP value), predictive power (ROC analysis and AUC value), and metabolite identification (MS/MS matching and retention time). The metabolites underwent analysis to determine their VIP scores, Fold Changes, and q-values. Additionally, metabolites underwent ROC analysis, with AUC values indicating the following levels of discriminatory power: below 0.7 suggests limited power, 0.7 to 0.8 indicates moderate efficacy, 0.8 to 0.9 suggests good identification accuracy, and 0.9 to 1.0 denotes excellent predictive capability12.

Following established criteria13, metabolites were categorized into five confidence levels, from Level 1 (highest confidence) to Level 5. Level 1 includes confirmed structures from BGI HR-PMDB with complete molecular ion, MS/MS spectrum, and retention time matches. Level 2 includes identifications from BGI HR-PMDB or mzCloud with matches in molecular ion and MS/MS spectrum but without retention time information. The identified metabolites were mapped against the KEGG database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) to enrich for implicated metabolic pathways.

Finally, biomarkers were identified based on q-value < 0.05, Fold Change ≥ 1.2 or ≤ 0.83, VIP ≥ 1, AUC 0.7–1.0, and confidence Levels 1–2.

Results

Characteristics of volunteers

In this study, we enrolled a total of 21 patients with acute myocarditis. According to the proposed stages of myocarditis from the ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Strategies and Criteria for the Diagnosis and Management of Myocarditis14, 19 patients were classified as Stage C (symptomatic myocarditis) and 2 patients as Stage D (advanced myocarditis). The average age of patients with acute myocarditis and healthy volunteers is 30.71 ± 10.11 years and 31.05 ± 9.75 years, respectively. Both groups are composed of an equal number of males (15) and females (6). In the acute myocarditis group, a significant majority, 85.7%, reported experiencing chest distress and/or chest pain. Additionally, a significant proportion, 90.4%, presented with symptoms indicative of an infection before hospitalization, such as fever, cough, rhinorrhea, or diarrhea. Cardiac function peak indicators were assessed, with NT-proBNP levels showing a median of 277 pg/mL, an interquartile range (IQR) of 125 to 1946 pg/mL. Troponin T (TnT) levels had a median of 469 ng/L, with an IQR of 267 to 1578 ng/L, and creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) levels presented a median of 27 U/L, IQR 13 to 58 U/L. For a comprehensive overview of the clinical signs, symptoms, and laboratory parameters of the acute myocarditis patients, please refer to Table 1.

Metabolomics results

Multivariate statistical analysis of metabolomics

PCA analysis for all samples including QC samples can be used to observe the overall distribution of samples in each group and the stability of the whole analysis process. The PCA results demonstrated that all QC samples were tightly clustered, validating the robustness of our analytical method (Fig. 1A). The PCA scores plot highlighted a significant divergence between the groups, and the subsequent PLS-DA model (Fig. 1B) provided an enhanced degree of separation, underscoring the effectiveness of the classification approach. Within the PCA model, the first principal component (PC1) explained 12.51% of the variability, while the second (PC2) accounted for 12.29%. Correspondingly, the PLS-DA model attributed 8.78% of the variability to PC1 and 4.41% to PC2.

Metabolic Discrimination of Acute Myocarditis Patients vs. Healthy Controls via PCA, PLS-DA, and OPLS-DA Analyses. (A) PCA score plot, including quality control samples. (B) PLS-DA score plot. (C) OPLS-DA score plot. (D) Validation plot for the OPLS-DA model, with R and Q2 values indicating model reliability (R = 0.0 to 0.79; Q2 = 0.0 to -0.30).

To ensure the model’s quality without overfitting, 200 response permutation tests (RPT) were executed on the OPLS-DA model (Fig. 1C). The goodness of fit parameters, R2Y (0.913) and Q2 (0.805), derived from the permuted dataset, were found to be lower than those of the original model. Additionally, the Q2 regression line exhibited a negative intercept (Fig. 1D). These findings confirmed the robustness of our metabolic profiling platform, suggesting that observed changes in biomarker levels are reflective of the disease state and not due to analytical artifacts.

Screening of differential metabolites

In this study, a comprehensive metabolomic analysis identified 33,074 metabolites, with 8,557 of these being confirmed as identifiable. These identified metabolites were categorized into four main groups: bioactive compounds, lipids, phytochemicals, and others, as illustrated in Fig. 2A. They were further found to be enriched across 13 KEGG pathways, depicted in Fig. 2B.

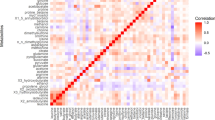

We utilized volcano plots (Fig. 3A) to visually represent the comparative analysis, highlighting significant metabolic shifts in the acute myocarditis group compared to the control group. Among the 8557 metabolites identified, 728 were found to be increased and 820 decreased (VIP ≥ 1, Fold Change ≥ 1.2 or ≤ 0.83, q-value < 0.05). Figure 3B presents a heatmap of cluster analysis, differentiating the acute myocarditis and control groups based on differential metabolite expression. Supplementary Figure S4 provides the results of correlation analysis of the differential metabolites.

Further, we conducted a metabolic pathway enrichment analysis on the differentially expressed metabolites, leveraging the KEGG database. Bubble plots were generated to visualize the top 10 most significant pathways with the lowest P-values, encompassing ABC transporters, 2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, proximal tubule bicarbonate reclamation, long-term depression, glutamatergic synapse, nicotine addiction, phenylalanine metabolism, GABAergic synapse reflecting metabolic disruptions associated with acute myocarditis (Fig. 4). Supplementary Table S1 provides a summary of these top ten metabolic pathways, detailing the smallest P-values obtained and the number of differentially expressed metabolites enriched in each pathway. This comprehensive overview aids in elucidating the intricate metabolic shifts that occur in the context of acute myocarditis.

Identification of potential metabolic biomarkers

Our study utilized a meticulous screening process to identify potential biomarkers. All Level 1 metabolites selected, along with a subset of Level 2 biomarkers with ROC-AUC values exceeding 0.9, are enumerated in Table 2 and discussed within the main text. Additional metabolites with Level 2 evidence and an AUC ranging from 0.7 to 0.9 are detailed in Supplementary Table 2. We confirmed 17 metabolites with level-1 evidence and an AUC exceeding 0.7. Potential biomarkers upregulated in acute myocarditis patients included indolelactic acid, L-glutamic acid, 4-pyridoxic acid (4-PA), N1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide (2-PY), palmitic acid, hydroxyphenyllactic acid (HPLA), riboflavin, nicotinic acid, choline, N-formylkynurenine, guanine, and hypoxanthine. Conversely, sebacic acid, 4-vinylphenol sulfate (4-VPS), capryloylglycine, 4-ethylphenylsulfate (4-EPS), and azelaic acid were found to be decreased. Additionally, we identified two metabolites upregulated in acute myocarditis patients with level-2 evidence and an AUC over 0.9, namely phytosphingosine and N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac). The discriminatory power of these potential biomarkers is visually represented through their ROC curves, as depicted in Fig. 5. The involvement of these biomarkers in various metabolic pathways is further highlighted in Fig. 6, showcasing their potential roles in the pathophysiology of acute myocarditis.

ROC Curve Analysis of 19 Potential Myocarditis Biomarkers. (A) phytosphingosine; (B) N-acetylneuraminic acid; (C) sebacic acid; (D) indolelactic acid; (E) L-glutamic acid; (F) 4-pyridoxic acid; (G) palmitic acid; (H) capryloylglycine; (I) 4-vinylphenol sulfate; (J) N1-Methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide; (K) hydroxyphenyllactic acid; (L) nicotinic acid; (M) choline; (N) riboflavin; (O) N-formylkynurenine; (P) guanine; (Q. 4-ethylphenylsulfate; (R) azelaic acid; (S) hypoxanthine.

Metabolic Shifts in Energy and Amino Acid Metabolism in Acute Myocarditis. This illustration, crafted with Figdraw, delineates the metabolic biomarkers that exhibit significant alterations in acute myocarditis patients relative to the control group. Red arrows indicate biomarkers with increased levels, while blue arrows signify those with decreased levels in the context of acute myocarditis. AOX aldehyde oxidase, AZA azelaic acid, FFA free fatty acid, F1,6-BP fructose-1,6-diphosphate, G6P glucose 6-phosphate, GLS glutaminase, G6PD glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, IDO indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, IMP hypoxanthine nucleotide, MPC mitochondrial pyruvate carrier, M-NAM, methyl nicotinamide, LDHA lactate dehydrogenase A, NaAD nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide, NAM nicotinamide, NAMN nicotinic acid mononucleotide, PA palmitic acid, PGLS phosphogluconolactonase, PRPP phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate, PKM2 pyruvate kinase m2, R5P ribulose 5-phosphate, SA sebacic acid, TDO tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase, α-KG α-ketoglutarate, 2PY N1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide, 3PG 3-phosphoglycerate, 4PY N1-methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide, 6PGL 6-phosphogluconolactone.

Discussion

The limited understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of acute myocarditis presents significant challenges in clinical diagnosis and treatment15. This pioneering cross-sectional study leveraged a non-targeted metabolomics approach to uncover crucial metabolic pathways associated with acute myocarditis. These include ABC transporters, 2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, and alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, among others. Furthermore, our research identified 19 biomarkers with a high level of confidence, potentially offering new insights into treatment strategies for this condition. In the following discussion, we will classify and examine these potential biomarkers.

Gastrointestinal microbiome and host amino acid metabolism

Imbalances in the gut microbiome, known as dysbiosis, and the associated metabolites are closely linked to cardiovascular disease (CVD) via the gut-heart axis16. Intriguingly, echoing the findings that gut microbiome markers were significantly altered in a mouse model of acute myocarditis8. Our study reveals that among the potential biomarkers for acute myocarditis, there is a notable decrease in 4-EPS levels alongside an increase in HPLA expression. These substances originate from the human intestinal microbiota’s metabolism of tyrosine17. While 4-EPS levels have been correlated with neurological changes associated with anxiety and the maintenance of intestinal barrier integrity18,19, its specific biological functions in the context of myocarditis remain unclear. Furthermore, HPLA has emerged as a potential biomarker for the early diagnosis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction20. HPLA, functions through activation of the HCA3 receptor, a Gi protein-coupled receptor. This activation inhibits adenylate cyclase, reduces cAMP levels, and consequently decreases free fatty acids (FFA), leading to reduced ATP production21. In myocardial tissue, this signaling cascade may contribute to the dysregulation of energy metabolism and impaired cardiac function observed in myocarditis patients. These gastrointestinal flora-related biomarkers underscore the pivotal role of the gut-heart axis in the pathogenesis of acute myocarditis.

Our study also revealed a significant increase in the urine content of indolelactic acid and N-formylkynurenine, both metabolites of tryptophan, in patients with acute myocarditis. Indolelactic acid, produced by gut bacteria from tryptophan, has demonstrated protective effects on cardiac cells through its anti-inflammatory properties22. Interestingly, the genomic excision of Paraoxonase 1, a gene associated with CVD, significantly lowered the serum level of indolelactic acid in mice23, which potentially contributes to the development of diseases. Protein-bound N-formylkynurenine has been identified as a biomarker for protein oxidation in the myocardium of aging rats24. N-formylkynurenine, an intermediate metabolite in the kynurenine pathway (KP), is initially converted from tryptophan by enzymes such as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) or tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) and then metabolized into kynurenine25. The relationship between kynurenine and myocarditis has been partially validated in animal models, where KP inhibition ameliorates acute viral myocarditis26. Mendelian randomization analysis further identifies elevated kynurenine is a significant risk factor for myocarditis27. Notably, KP regulates inflammation, oxidative stress and immune responses during acute heart attack28. Therefore, regulation of KP may provide an effective strategy for treating acute viral myocarditis.

L-Glutamic acid, a non-essential amino acid, is vital for heart health, participating in both protein synthesis and myocardial energy metabolism. Patients with heart failure or those with heart injury due to cardiac stimulation may experience benefits from L-glutamic acid supplementation29. Moreover, L-glutamic acid plays a crucial role in preventing myocardial oxidative damage30. Prior research by Qing Kong and colleagues showed a significant decrease in cardiac tissue L-glutamic acid in a mouse model of acute viral myocarditis, potentially contributing to severe cardiac inflammation and fibrosis7. However, our data indicate a significant increase in urinary L-glutamic acid in acute myocarditis patients. The discrepancy in results might be attributed to the over-excretion of L-glutamic acid in urine, causing a relative reduction in its content within cardiac tissue.

Lipid metabolism

Phytosphingosine, a distinct type of sphingolipid, has garnered attention in our research for its significantly elevated levels in acute myocarditis patients when compared to control subjects. This prominence has led to its identification as a potential biomarker for acute myocarditis, with an impressive AUC of 0.968. Furthermore, our findings are in line with previous studies that have observed a correlation between high plasma concentrations of phytosphingosine and an increased risk of coronary atherosclerosis in patients31. This association underscores the significance of phytosphingosine in heart health. Beyond its implications for heart disease, phytosphingosine is also being considered a potential biomarker for renal impairment32. The potential pathological mechanisms of phytosphingosine involve its role in the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS)33. These ROS are known to disrupt mitochondrial integrity, potentially leading to the triggering of cell apoptosis.

Palmitic acid levels are significantly elevated in patients with acute myocarditis, originating from both dietary fats and endogenous sources such as de novo lipogenesis and lipolysis. Serum levels of palmitic acid have been identified as biomarkers for the CVD risk34. The impact of palmitic acid on CVD risk extends beyond its role in increasing low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels, it also includes the synthesis of ceramides and potentially the formation of branched fatty acid esters of hydroxy fatty acids derived from palmitic acid35. Furthermore, palmitic acid has been shown to induce lipotoxic damage to cardiomyocytes, which is manifested as inflammation and apoptosis36,37.

Sebacic acid and azelaic acid levels are significantly decreased in patients with acute myocarditis. As a primary medium-chain fatty acid, sebacic acid is oxidized to azelaic acid, which is then shortened by multiple β-oxidations to form short-chain dicarboxylic acids. These ultimately enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle38. Acute myocarditis is pathologically characterized by significant cardiac inflammatory responses. Azelaic acid, an aliphatic dicarboxylic acid, possesses anti-inflammatory properties39. These observations suggest a correlation between lipid metabolism and the progression of acute myocarditis, highlighting the need for further research into its role in cardiac pathophysiology.

Carbohydrate metabolism

Neu5Ac, the predominant form of sialic acid, plays a pivotal role as the terminal component of cell-surface glycoconjugates, including glycoproteins and glycolipids40. Recent studies have indicated that Neu5Ac, serving as a metabolic marker, is significantly elevated during the progression of coronary artery disease and acts as a signaling molecule that triggers RhoA and Cdc42-dependent myocardial injury41. The therapeutic potential of Neu5Ac inhibition is suggested by studies where oseltamivir, a neuraminidase inhibitor, has been shown to mitigate myocardial injury in heart failure models in vivo42. These findings highlight Neu5Ac as a promising target for treating myocardial injury. This study’s most compelling finding is the significant elevation of urinary Neu5Ac levels, with an AUC of 0.955, observed in patients with acute myocarditis. This elevated Neu5Ac could serve as a diagnostic and monitoring biomarker for acute myocarditis, indicating a need for further research to validate its clinical utility.

Metabolism of coenzymes, vitamins, and vitamin-like substances

In patients with acute myocarditis, alterations within the vitamin B complex were identified, marked by elevated levels of four key metabolites: nicotinic acid, 4-PA, 2-PY and riboflavin. Nicotinic acid, historically used for treating atherogenic hyperlipidemia by virtue of its contribution to reducing LDL cholesterol levels and increasing HDL-C levels43. Recent metabolomic studies further revealed impaired nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism in cardiac tissues of Coxsackievirus B3-infected mouse models7. Both 4-PA, a degradation product of vitamin B6, and riboflavin are potent antioxidants, instrumental in nucleic acid synthesis and the prevention of tissue and organ aging44,45. Additionally, 2-PY, a metabolite of the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD +), has been linked to CVD risk46. Notably, elevated 2-PY levels were found in the urine of mice on a high-fat diet, coincident with an upregulation of mitochondrial oxidative pathways47. These findings collectively underscore a potential link between vitamin B metabolism dysregulation, oxidative stress, and myocardial inflammation.

Our research also documented significantly increased choline levels in the urine of acute myocarditis patients. Choline, a precursor to the vital neurotransmitter acetylcholine and classified as a vitamin-like substance, has demonstrated cardiovascular benefits in conditions such as hypertension, myocardial infarction, and myocardial hypertrophy48. Its cardioprotective effects are attributed to the inhibition of ROS, regulation of mitochondrial dysfunction, and mitigation of inflammatory responses49,50. However, a higher baseline level of choline has been associated with an elevated risk of atrial fibrillation and heart failure51.

Nucleotide metabolism

In the realm of nucleotide metabolism and its metabolomic profile, significant alterations within the purine pathway are evidenced by elevated levels of guanine and hypoxanthine. Hypoxanthine, an intermediate in purine catabolism, is converted into xanthine by the catalytic action of xanthine oxidase, a process accompanied by the generation of ROS, which can induce cytotoxicity52. It has been demonstrated that heightened extracellular hypoxanthine concentrations can precipitate endothelial dysfunction via ROS-mediated mechanisms and modulate the expression of proteins implicated in apoptosis within human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)53. This dysregulation underscores the potential for intensified nucleotide metabolism to exacerbate the progression of acute myocarditis.

Others

Our findings also point to potential associations between acute myocarditis and the reduced urinary levels of capryloylglycine and 4-VPS. Capryloylglycine has previously exhibited effective predictive value in identifying chronic subdural hematoma through urine metabolomics analysis54. 4-VPS, a primary metabolite of 4-vinylphenol, is found naturally in crops like peanuts and wild rice55. A large-scale Mendelian randomization study has linked elevated 4-VPS levels to a 22% increased risk of heart failure for every standard deviation rise56. These insights may contribute to a broader understanding of acute myocarditis pathogenesis.

In summary, this pioneering research has identified 19 potential biomarkers associated with the progression of acute myocarditis, encompassing areas such as the gastrointestinal microbiome and host amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, and nucleotide metabolism. Certain markers have been linked to inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with acute myocarditis. However, there are limitations to this study. Given the low incidence of myocarditis, the sample size we were able to collect was constrained. Although the study design accounted for age and gender matching, other confounding factors—such as comorbidities and diet—could potentially introduce bias into the results. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of this research precludes the establishment of a causal link. Additional studies are needed to delve into the pathological roles of these markers and to evaluate their potential as diagnostic indicators for acute myocarditis. This will involve more in-depth analysis and potentially longitudinal studies to better understand their roles in acute myocarditis development and progression.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data is available on Metabolights (Accession Number MTBLS11759).

References

Ammirati, E. & Moslehi, J. J. Diagnosis and treatment of acute myocarditis: A review. Jama 329, 1098–1113. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.3371 (2023).

Jiang, J. et al. Chinese Society of Cardiology guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of adult fulminant myocarditis. Sci. China Life Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-023-2421-0 (2024).

Spotts, P. H. & Zhou, F. Myocarditis and pericarditis. Primary Care 51, 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2023.07.006 (2024).

Tschöpe, C. et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: Current evidence and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-00435-x (2021).

Schrimpe-Rutledge, A. C., Codreanu, S. G., Sherrod, S. D. & McLean, J. A. Untargeted metabolomics strategies-challenges and emerging directions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 27, 1897–1905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-016-1469-y (2016).

Kong, Q. et al. NMR-based metabolomic analysis of sera in mouse models of CVB3-induced viral myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Biomolecules https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12010112 (2022).

Kong, Q. et al. NMR-based metabolomic analysis of cardiac tissues clarifies molecular mechanisms of CVB3-induced viral myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol. (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27186115 (2022).

Kong, Q. et al. Alterations of the gut microbiome and metabolic profile in CVB3-induced mice acute viral myocarditis. BMC Microbiol. 23, 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-023-02863-4 (2023).

Nagai, T. et al. JCS 2023 guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of myocarditis. Circ. J. 87, 674–754. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-22-0696 (2023).

Zeng, S. et al. Metabolomic analysis of porcine intestinal epithelial cells during swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1079297. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1079297 (2022).

Wen, B., Mei, Z., Zeng, C. & Liu, S. metaX: a flexible and comprehensive software for processing metabolomics data. BMC Bioinform. 18, 183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-017-1579-y (2017).

Xia, J., Broadhurst, D. I., Wilson, M. & Wishart, D. S. Translational biomarker discovery in clinical metabolomics: An introductory tutorial. Metabolomics 9, 280–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-012-0482-9 (2013).

Schymanski, E. L. et al. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: Communicating confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 2097–2098. https://doi.org/10.1021/es5002105 (2014).

Drazner, M. H. et al. 2024 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on strategies and criteria for the diagnosis and management of myocarditis: A report of the American College of Cardiology solution set oversight committee. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2024.10.080 (2024).

Jiang, J. et al. Chinese Society of Cardiology guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of adult fulminant myocarditis. Sci. China Life Sci. 67, 913–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-023-2421-0 (2024).

Tang, W. H., Kitai, T. & Hazen, S. L. Gut microbiota in cardiovascular health and disease. Circ. Res. 120, 1183–1196. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.117.309715 (2017).

Dodd, D. et al. A gut bacterial pathway metabolizes aromatic amino acids into nine circulating metabolites. Nature 551, 648–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24661 (2017).

Ahmed, H. et al. Microbiota-derived metabolites as drivers of gut-brain communication. Gut Microbes 14, 2102878. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2022.2102878 (2022).

Needham, B. D. et al. A gut-derived metabolite alters brain activity and anxiety behaviour in mice. Nature 602, 647–653. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04396-8 (2022).

Zhou, J. et al. Metabolomics analysis identifies differential metabolites as biomarkers for acute myocardial infarction. Biomolecules https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14050532 (2024).

Peters, A. et al. Metabolites of lactic acid bacteria present in fermented foods are highly potent agonists of human hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 3. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008145 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Novel risk score model for non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy based on untargeted metabolomics of venous blood. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1180415. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1180415 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Alteration of the intestinal microbiota and serum metabolites in a mouse model of Pon1 gene ablation. Faseb J. 38, e23611. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202302344R (2024).

Cebe, T. et al. A comprehensive study of myocardial redox homeostasis in naturally and mimetically aged rats. Age (Dordr.) 36, 9728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-014-9728-y (2014).

Murakami, Y. et al. Depressive symptoms as a side effect of Interferon-α therapy induced by induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1. Sci. Rep. 6, 29920. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29920 (2016).

Hoshi, M. et al. L-tryptophan-kynurenine pathway metabolites regulate type I IFNs of acute viral myocarditis in mice. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 188, 3980–3987. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1100997 (2012).

Wang, Z., Tian, H. & Wang, J. Association between human blood metabolome and risk of myocarditis: A Mendelian randomization study. Sci. Rep. 14, 26494. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78359-6 (2024).

Gáspár, R. et al. Kynurenine pathway metabolites as potential clinical biomarkers in coronary artery disease. Front. Immunol. 12, 768560. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.768560 (2021).

Durante, W. The emerging role of l-glutamine in cardiovascular health and disease. Nutrients 11, 2092. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092092 (2019).

Geng, C. et al. Systematic evaluations of doxorubicin-induced toxicity in rats based on metabolomics. ACS Omega 6, 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c04677 (2021).

Gao, X. et al. Large-scale metabolomic analysis reveals potential biomarkers for early stage coronary atherosclerosis. Sci. Rep. 7, 11817. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12254-1 (2017).

Zhao, Y. Y., Liu, J., Cheng, X. L., Bai, X. & Lin, R. C. Urinary metabonomics study on biochemical changes in an experimental model of chronic renal failure by adenine based on UPLC Q-TOF/MS. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 413, 642–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2011.12.014 (2012).

Li, J. et al. Phytosphingosine-induced cell apoptosis via a mitochondrially mediated pathway. Toxicology 482, 153370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2022.153370 (2022).

Hu, T. et al. Machine learning reveals serum myristic acid, palmitic acid and heptanoylcarnitine as biomarkers of coronary artery disease risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 556, 117852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2024.117852 (2024).

Annevelink, C. E., Sapp, P. A., Petersen, K. S., Shearer, G. C. & Kris-Etherton, P. M. Diet-derived and diet-related endogenously produced palmitic acid: Effects on metabolic regulation and cardiovascular disease risk. J. Clin. Lipidol. 17, 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2023.07.005 (2023).

Guo, L. et al. Baicalein ameliorated obesity-induced cardiac dysfunction by regulating the mitochondrial unfolded protein response through NRF2 signaling. Phytomedicine 126, 155441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155441 (2024).

Yue, Q. et al. Downregulation of growth arrest-specific transcript 5 alleviates palmitic acid-induced myocardial inflammatory injury through the miR-26a/HMGB1/NF-κB axis. Mol. Med. Rep. 18, 5742–5750. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2018.9593 (2018).

Liao, Z., Alrosan, M., Alu’datt, M. H. & Tan, T. C. 10-hydroxy decanoic acid, trans-10-hydroxy-2-decanoic acid, and sebacic acid: Source, metabolism, and potential health functionalities and nutraceutical applications. J. Food Sci. 89, 3878–3893. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.17143 (2024).

Cai, W. et al. Does urinary metabolite signature act as a biomarker of post-stroke depression?. Front. Psychiatry 13, 928076. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.928076 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Increasing brain N-acetylneuraminic acid alleviates hydrocephalus-induced neurological deficits. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 29, 3183–3198. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.14253 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Functional metabolomics characterizes a key role for N-acetylneuraminic acid in coronary artery diseases. Circulation 137, 1374–1390. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.117.031139 (2018).

Li, C. et al. Prognostic Value of Elevated Levels of Plasma N-Acetylneuraminic Acid in Patients With Heart Failure. Circulation. Heart Fail. 14, e008459. https://doi.org/10.1161/circheartfailure.121.008459 (2021).

Digby, J. E., Lee, J. M. & Choudhury, R. P. Nicotinic acid and the prevention of coronary artery disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOL.0b013e32832d3b9d (2009).

Lewis, J. S. & Nunn, K. P. Vitamin B6 intakes and 24-hr 4-pyridoxic acid excretions of children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 30, 2023–2027. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/30.12.2023 (1977).

Suwannasom, N., Kao, I., Pruß, A., Georgieva, R. & Bäumler, H. Riboflavin: The health benefits of a forgotten natural vitamin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21030950 (2020).

Ferrell, M. et al. A terminal metabolite of niacin promotes vascular inflammation and contributes to cardiovascular disease risk. Nat. Med. 30, 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02793-8 (2024).

Boulangé, C. L. et al. Early metabolic adaptation in C57BL/6 mice resistant to high fat diet induced weight gain involves an activation of mitochondrial oxidative pathways. J. Proteome Res. 12, 1956–1968. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr400051s (2013).

Guo, F. et al. Choline protects the heart from doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through vagal activation and Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 4740931. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4740931 (2022).

Xu, M. et al. Choline ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy by regulating metabolic remodelling and UPRmt through SIRT3-AMPK pathway. Cardiovasc. Res. 115, 530–545. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvy217 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Choline ameliorates cardiovascular damage by improving vagal activity and inhibiting the inflammatory response in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Sci. Rep. 7, 42553. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42553 (2017).

Papandreou, C. et al. Choline metabolism and risk of atrial fibrillation and heart failure in the PREDIMED study. Clin. Chem. 67, 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvaa224 (2021).

Yin, H., Liu, N. & Chen, J. The Role of the Intestine in the Development of Hyperuricemia. Front. Immunol. 13, 845684. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.845684 (2022).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Hypoxanthine causes endothelial dysfunction through oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 482, 821–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.119 (2017).

Sun, J. et al. LC-MS-based urine metabolomics analysis of chronic subdural hematoma for biomarker discovery. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 18, e2200107. https://doi.org/10.1002/prca.202200107 (2024).

Leung, H. W., Ko, C. H., Yue, G. G., Herr, I. & Lau, C. B. The natural agent 4-vinylphenol targets metastasis and stemness features in breast cancer stem-like cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 82, 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-018-3601-0 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Using a two-sample Mendelian randomization method in assessing the causal relationships between human blood metabolites and heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 695480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.695480 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to BGI for providing testing and technical support, and to the volunteers who participated in the project.

Funding

This research is financially supported by the "Discipline Top Talent Scientific Research Fund" from the Zhongshan city people’ hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments (WYZ, YRL). Performed the experiments: (XZL, CMZ, KYW). Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: (KYW, SXT). Wrote the paper: (CMZ, WYZ, XZL). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Cm., Long, Xz., Wang, Ky. et al. High-throughput untargeted metabolomic profiling of urinary biomarkers in acute myocarditis patients: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 9254 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93655-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93655-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparison of various data preprocessing software for untargeted urinary metabolomics using UHPLC-HRMS to diagnose cancer

Iran Journal of Computer Science (2025)