Abstract

Objective measurements of pain and safe methods to alleviate it could revolutionize medicine. This study used functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and virtual reality (VR) to improve pain assessment and explore non-pharmacological pain relief in cancer patients. Using resting-state fNIRS (rs-fNIRS) data and multinomial logistic regression (MLR), we identified brain-based pain biomarkers and classified pain severity in cancer patients. Participants included healthy individuals who underwent rs-fNIRS recording without VR (Group A), cancer patients who underwent rs-fNIRS recording both before and after engaging in the Oceania relaxation program VR intervention (Group B), and cancer patients who underwent rs-fNIRS recording without VR (Group C). All participants wore a wireless fNIRS headcap for brain activity recording. Pain severity was self-reported by patients using the FACES Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R). fNIRS data were analyzed with MLR, categorizing pain into no/mild (0–4/10), moderate (5–7/10), and severe (8–10/10) levels. The MLR model classified pain severity in an unseen test group, selected using the leave-one-participant-out technique and repeated across all participants, achieving an accuracy of 74%. VR significantly reduced pain intensity (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.001), with significant changes in brain functional connectivity patterns (P < 0.05). Additionally, 75.61% of patients experienced pain reductions exceeding the clinically relevant threshold of 30%. These findings underscore the potential of fNIRS for pain assessment and VR as a useful non-pharmacological intervention for cancer-related pain management, with broader implications for clinical pain management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Uncontrolled pain substantially affects many cancer patients’ quality of life and treatment adherence1,2. An estimated 60–80% of cancer pain is not properly managed, with 40% of patients experiencing severe pain in the late stages of their lives3. This can lead to hopelessness, depression, anxiety, and increased suicide risk, with cancer patients having a doubled suicide rate compared with the general population4,5,6. The lack of objective pain assessment methods hinders balanced pain management, in which both analgesia and side effects must be considered7,8.

Prediction of perceived pain severity

The gold standard for assessing pain severity in cancer patients is represented by self-reported scales, such as the Brief Pain Inventory and the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory9,10 and questionnaire such as McGill Pain Questionnaire13. However, these methods, being subjective, may introduce bias, and certain patients, due to cognitive impairments or disabilities, might be unable to accurately use them11,12. Development of an objective pain assessment method is essential to improving pain management in cancer patients because this would enable clinicians to understand and manage pain more effectively and enable personalized pain management strategies.

Recent progress in neuroimaging, specifically functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), combined with machine learning (ML), presents promising opportunities for investigating the neurophysiological aspects of pain and creating tools for assessing pain severity14. fNIRS is a non-invasive technique that measures changes in cerebral blood oxygenation reflective of neural activity. The resting state is a natural condition characterized by the absence of overt perceptual input or behavioral output and is convenient to set up. Resting-state fNIRS (rs-fNIRS) reflects spontaneous, intrinsic brain activity and is therefore a fundamental framework for studying brain function15.

Currently, ML techniques are increasingly being applied to neuroimaging data to identify brain activity patterns associated with different health conditions16. Nevertheless, several studies combining fNIRS and ML for pain assessment have typically relied on induced pain stimuli (such as pressure or thermal tests) rather than assessment of naturally occurring pain in patients16,17,18,19. Hence, research in clinical settings is now needed to address this knowledge gap.

This study employed rs-fNIRS data and ML to link brain functional connectivity patterns with cancer-related pain severity and identify pain biomarkers for enhanced assessments during pain management.

Non-pharmacological pain management methods

Distraction, a popular non-pharmacologic approach for pain management, involves diverting attention from pain through engaging thoughts or activities20. Virtual reality (VR) may hold promise for distracting patients’ attention from pain21. However, further research is needed to comprehensively understand the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms. A dual aim of this study is to explore how VR program alleviate pain in cancer patients and to identify which brain regions show changes in functional connectivity with other regions due to VR.

Pain in the brain

The thalamus and limbic system, including the hippocampus and amygdala, play central roles in pain processing. The thalamus functions as a relay for sensory information, while the limbic system controls emotional and behavioral responses to pain22,23. Additionally, the cingulate cortex, insular cortex, primary and secondary somatosensory cortices, and prefrontal cortex play significant roles in the multidimensional experience of pain22,23,24,25,26. The cingulate cortex is implicated in the emotional aspects of pain, integrating affective responses27. The insular cortex contributes to the interoceptive awareness of pain, processing sensory information related to bodily states28. The primary somatosensory cortex is essential for the localization and discrimination of pain stimuli, while the secondary somatosensory cortex is involved in the integration of sensory modalities and the perception of pain intensity29. The prefrontal cortex plays a role in higher-order cognitive functions, including the modulation of pain perception through attention and emotional regulation30.

While rs-fNIRS is suitable for studying surface-level cortical activities, it has limited ability to probe deep structures due to the shallow penetration of near-infrared light31. fNIRS was chosen for this study due to its portability, non-invasiveness, and ability to measure hemodynamic responses, making it well-suited for assessing pain in a clinical setting. Compared to other brain mapping techniques, fNIRS offers unique advantages:

-

While electroencephalogram (EEG)32 also provides portable and non-invasive measurements, it captures electrical activity rather than hemodynamic changes, which limits its ability to assess vascular components of pain processing.

-

Techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)33, positron emission tomography (PET)34, and magnetoencephalography (MEG)35 provide higher spatial resolution or molecular understandings but are costly, less accessible, and not practical for bedside or continuous monitoring.

The prefrontal cortex, superior frontal gyrus, and left/right parietal cortices, accessible to fNIRS, play crucial roles in pain processing36,37. The prefrontal cortex handles the cognitive appraisal of pain, the superior frontal gyrus contributes to the emotional and cognitive aspects of pain, and the parietal cortex processes sensory information of pain. The connectivity between these brain regions is vital for integrating sensory, cognitive, and emotional aspects of pain processing, while effective communication indicates efficient pain signal processing and response formulation38,39. Disruptions in this connectivity can lead to altered pain perception and responses.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and was approved by the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Institutional Review Board (Roswell Park; IRB number: 1720121; PI: Somayeh B Shafiei; date of approval: October 17, 2021). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardian(s). Healthy participants from the Roswell Park employees participated in group A. Cancer patients from the Roswell Park outpatient pain clinic participated in groups B and C.

System setup time varied, with up to 10 min used for participants with thick, dark hair, and less time used for those with light or thin hair; only about 1 min was needed for bald or white-haired individuals.

In Group A, healthy participants wore fNIRS headcaps for 10 min of rs-fNIRS recording. In Group B, pain-afflicted cancer patients wore headcaps for 29 min (10 min before VR, 9 min during the VR program, and 10 min after VR). The fNIRS system remained in place after the initial rs-fNIRS recording during the VR session, enabling an immediate transition to the second rs-fNIRS recording following the session. In Group C, pain-afflicted cancer patients wore headcaps for 10 min of rs-fNIRS recording.

FACES pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R)

Pain severity in cancer patients in Group C was measured using the FACES Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R) before the rs-fNIRS recording and, for Group B, before and after the VR program. FPS-R is a tool widely used in medicine to assess the intensity of perceived pain. It is an updated version of the original Faces Pain Scale, which includes a set of faces to indicate different pain intensities along with a numeric scale (usually 0–10) above or below the faces40.

Patients used the FPS-R to assess their pain level by selecting a specific image on a visual scale. Participants in Group C, who only underwent rs-fNIRS recording without VR, used the FPS-R to assess their perceived pain severity approximately 15 min before the start of the recording. Participants in Group B, who underwent both rs-fNIRS recording and the VR program, assessed their pain severity twice: 15 min before their first rs-fNIRS recording, and up to 15 min after completing the VR session (equivalent to 5 min after their second rs-fNIRS recording, as each rs-fNIRS recording lasts 10 min). The timeline for each step of data recording is shown in Fig. 1. Participants in Groups A and C completed only steps A to C (Fig. 1), while participants in Group B completed all steps from A to F (Fig. 1).

Timeline for each step of data recording: (A) Pain severity self-assessment, (B) fNIRS setup, (C) rs-fNIRS recording, (D) Engagement in VR program, (E) rs-fNIRS recording, and (F) Pain severity self-assessment. This figure was generated using the ChatGPT 4 AI, which assisted in the creation of visual elements.

Recruitment

Participants were invited to the study through email and/or verbal invitations. Thirteen healthy participants participated in the rs-fNIRS recording experiment (Group A). Forty-one cancer patients with pain participated in both the VR intervention and rs-fNIRS recording before and after VR (Group B), and 93 cancer patients participated only in the rs-fNIRS recording experiment (Group C). Recruitment and data collection took place over a 24-month period. All participants provided their written consent.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

All participants had to be free from neurologic and psychiatric illnesses, e.g., stroke.

-

Participants in Groups B and C had no brain metastases which could interfere with brain functions.

-

Participants should be able to remain sedentary for the duration of the sessions and must remove any items, such as wigs or hijabs, that could interfere with the fNIRS optodes’ contact with the skin.

-

Female participants must not be pregnant to ensure that the study’s brain activity data collection is not affected by pregnancy-related factors because during the third trimester, the fetus’s brain is significantly developed and may interact with the mother’s brain41.

-

Participants had to be free from electronic or metallic implants in the head.

-

For Group A, participants had to be free from cancer and cancer pain, and free from other forms of chronic pain e.g. rheumatologic pain.

-

For Group B, participants had to be free from hypersensitivity to flashing lights or motion, as this could lead to an increased risk of seizures or discomfort when using VR.

-

For group B, participants had to be free from impaired stereoscopic vision or severe hearing impairments due to the immersive visual and auditory nature of VR programs.

-

For Group B, participants had to be free from medical conditions that predispose them to nausea or dizziness because these symptoms could worsen during VR use.

rs-fNIRS data recording

The fNIRS uses near-infrared light (wavelength range: 650–900 nm) to penetrate the skull, measuring changes in blood oxygenation and volume in the brain’s cortex. This is done by placing optodes on the scalp; these emit light that, after interacting with brain tissue, is detected and analyzed for blood oxygen and flow changes. Optodes are components of the fNIRS system, consisting of both emitters (sources), which transmit near-infrared light into the tissue, and receivers (detectors), which capture the reflected light after it has traveled through the tissue.

In this study, rs-fNIRS data were collected using a wireless Dual Brite system and Oxysoft 3.3 software (Artinis Medical Systems®, Netherlands). A Dual Brite fNIRS system was used to cover a larger area of the brain, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis of the regions affected by pain. The optodes from the system were mounted on a single headcap. Participants were instructed to keep their eyes closed (Fig. 2A) and remain awake during the 10-minute rs-fNIRS recording42,43. Data was captured from the superior frontal gyrus (Fig. 2B) using a 10-channel setup, created by selectively pairing 1 emitter with 1 receiver to establish 10 unique channels from a possible combination of 4 emitters and 4 receivers. fNIRS data from the parietal cortex (Fig. 2C,D) were captured using two 5-channel setups, each formed by pairing 1 emitter with 1 receiver to create 5 unique channels from a possible combination of 3 emitters and 2 receivers. The prefrontal cortex was monitored using 24 channels with combinations of 10 emitters and 8 receivers (Fig. 2E). A total of 44 channels were used for data recording. The system measured the absorption of near-infrared light at two wavelengths (760 and 850 nm) at a sampling rate of 50 Hz.

Schematic of the resting-state fNIRS recording configuration. This setup illustrates the arrangement of light-emitting sources and receiving detectors using a wireless Dual Brite system (Artinis®) for capturing fNIRS data. Panel (A) depicts a patient in a seated, eyes-closed posture during data acquisition. The distribution of channels is detailed across the superior frontal gyrus (Channels 30–39, Panel B), left parietal lobe (Channels 40–44, Panel C), right parietal lobe (Channels 25–29, Panel D), and prefrontal cortex (Channels 1–24, Panel E). This figure was partially generated using the ChatGPT 4 AI, which assisted in the creation of certain visual elements.

Virtual reality program

Participants in Group B used a Meta-Quest 2 VR headset to engage in the 9-minute Oceania relaxation program from the Meta Store44. This immersive experience shows marine life around Australia and New Zealand, aiming to distract patients’ attention from pain (Fig. 3). Sessions were supervised by a clinical research faculty.

Schematic illustration of fNIRS data acquisition before and after the Oceania virtual reality experience. Panel (A) shows a patient seated with the fNIRS system in place, coupled with a Meta Quest 2 VR headset, during capture of cerebral hemodynamic responses while engaged with the virtual environment (B). Panel (A) of this figure was generated using the ChatGPT 4 AI.

Data and statistical analysis

FNIRs data preprocessing

The fNIRS data were pre-processed in the NIRS toolbox, a MATLAB-based analysis program for NIRS45. MATLAB 2022 software was used for this analysis. The following pre-processing steps were applied to the fNIRS data:

-

1.

The raw light intensity measurements from the fNIRS device were converted into optical density values, which are more suitable for quantitative analysis.

-

2.

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) method was used to remove the first main component and reduce physiological noises, such as those from motion46.

-

3.

For motion artifact detection and correction, we used the motion_correct function from the NIRS toolbox. This method was specifically chosen for its effectiveness in identifying and reducing motion-related artifacts, which are common issues in fNIRS recordings. Based on this function of the toolbox, the fNIRS signal is processed to create lagged versions of itself, incorporating information about the signal’s past behavior. Using these lagged signals, the function performs a regression analysis to model the relationship between the current signal and its previous values. This approach facilitates identifying and removing components of the signal that are likely due to motion artifacts. Toolbox then applies another filter to further correct motion artifacts. This involves assigning different weights to different parts of the signal, giving less importance to parts of the signal that were likely to be corrupted by motion. These weights are then used to adjust the filtered signal, thereby ensuring that the correction process does not distort the true neural signal.

-

4.

After correcting motion artifacts in the data, we implemented a bandpass filter with a passband range from 0.01 Hz to 0.1 Hz on the signals to restrict the frequency range15,47.

-

5.

Following bandpass filtering, the wavelet filter with the “Sym8” basis was used to further refine the signal by breaking it down into components at different scales and use those to identify and remove any remaining artifacts or noise.

Finally, we applied the modified Beer–Lambert law with a partial pathlength factor of 6 to compute the hemodynamic parameters and use those for feature extraction. This step involved converting the processed optical density data into measures of relative changes in concentrations of oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR).

After preprocessing, functional connectivity between pairs of channels was calculated using coherence analysis for HbO and HbR signals individually.

Functional connectivity features

HbO and HbR signals were used to extract fNIRS-based functional connectivity features. The first minute of the signals was excluded from further analysis to ensure that participants were resting and relaxed. The rs-fNIRS data were normalized to have a zero mean and unit variance, ensuring consistency and comparability across different recording sessions and participants47. To extract the functional connectivity between different fNIRS channels, coherence analysis was performed. This involved calculating the magnitude-squared coherence between pairs of channels across the entire dataset. The spectral analysis was carried out using a Hamming window with 50% overlap to calculate the magnitude-squared coherence. The number of Fast Fourier Transform (nFFT = 5000) points was determined based on the low-pass filter (LPF; 0.01 Hz) settings and sampling rate of the data (50 Hz).

We analyzed the rs-fNIRS signals by calculating functional connectivity between all pairs of channels to create functional connectivity matrices. With 44 channels, each resulting matrix has dimensions of 44 × 44 for both HbO and HbR. Since these matrices are symmetric, the number of unique functional connectivity features for HbO and HbR individually is (\(\:\frac{{44}^{2}-44}{2})\). Hence, a total of 946 functional connectivity features were extracted for each signal type, resulting in 1892 features per recording.

HbO coherence primarily reflects changes in oxygen delivery and consumption, which is associated with higher metabolic demands and neuronal activity in the corresponding brain regions33,48. Previous neuroimaging studies indicate that heightened metabolic demands during cognitive or sensory tasks lead to increased blood flow and oxygenation33,48. The coupling of neural activity to hemodynamic responses, known as neurovascular coupling, underscores the importance of HbO coherence in understanding brain function49. Thus, HbO coherence is a valuable metric for assessing the dynamic changes in oxygenation that accompany varying levels of neuronal engagement, providing understanding about the metabolic underpinnings of brain activity33,48. In contrast, HbR coherence offers estimation about the oxygen extraction process and venous blood oxygenation, which can vary depending on local cerebral blood flow and metabolic coupling50,51,52. In current study, coherence analyses for HbO were interpreted as a representation for neuronal activation and functional connectivity, while HbR coherence provided complementary information about the efficiency of oxygen usage and potential alterations in vascular dynamics.

Samples used for the pain prediction model

The study included three groups of participants: 13 in Group A, 41 in Group B, and 93 in Group C. Recordings from Groups A and C were used to develop a pain prediction model. Two rs-fNIRS recordings were obtained from 23 patients at two distinct follow up appointments, while a single recording was obtained from 70 patients in Group C. In total, 129 recordings (i.e., 23 × 2 + 70 + 13) were used to develop the pain prediction model.

Classification of perceived pain severity

We classified pain into no/mild, moderate, and severe categories. Pain severity for healthy participants is 0 (i.e., no pain). Labels for perceived pain severity were assigned as follows: Class 1: for no/mild pain (FPS-R: 0–4), Class 2: moderate pain (FPS-R: 5–7), and Class 3: severe pain (FPS-R: 8–10)53. Using all 11 scores (0 and 1 to 10) for assessment would require a much larger sample size to develop a reliable prediction model. Given the available data, classifying pain into three severity levels—no/mild, moderate, and severe—was a more feasible approach.

The study used fNIRS functional connectivity features and subjectively assessed pain severity labels to train, validate, and test a multinomial logistic regression (MLR) model with three output classes. We used Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) from the scikit-learn library, which incorporated MLR as the estimator. This method performed recursive feature elimination and simultaneously determined the optimal number of features based on cross-validated model performance.

To ensure robust testing, we implemented the leave-one-participant-out cross-validation method, whereby all samples from one participant were reserved for the test set, and the remaining samples were used for training–validation (Fig. 4). This cycle was repeated for each participant, ensuring that every individual’s data contributed to the test set, thus facilitating a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance.

The model’s key parameters were optimized using grid search with stratified 5-fold cross-validation, repeated five times. This process was nested within a leave-one-participant-out cross-validation framework to ensure robust evaluation. The stratified 5-fold cross-validation ensured class label distribution was preserved. For model optimization, samples from a participant were placed either in the training fold or the validation fold, but not in both. The scikit-learn toolbox of Python 3.7 was used to develop the MLR model. The Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique (SMOTE) with k-neighbors = 5 was applied to address class imbalance within the training folds. This setting means that for each sample in the minority class, synthetic samples were generated by interpolating between the sample and its 5 nearest neighbors.

Tuning the key parameters of the logistic regression model

Logistic regression is a linear classification algorithm used to model the probability of certain classes or events. It estimates the probability of an instance belonging to a particular class using a logistic function. The main hyperparameters (i.e., key parameters) for logistic regression and the values considered for each parameter for tuning are explained briefly here. The “Penalty” parameter specifies the type of regularization applied in the model. Regularization is an essential technique employed to prevent overfitting, a common issue where a model excessively learns from the training data, which detriments the model’s performance on new data. This can be achieved by incorporating a regularization term into the model’s loss function. The nature of this regularization term can vary (e.g., L1, L2, or a combination of them). Each type of regularization term imposes different constraints on the model coefficients. L1 makes the model use fewer features by setting some coefficients to zero, while L2 keeps all features but makes the coefficients smaller and more evenly spread out. In the given model, “C” serves as the inverse of regularization strength. We considered a range from 0.1 to 1 for this parameter, increasing it in increments of 0.1 to fine-tune the regularization effect. A smaller value of C results in stronger regularization, and a larger value of C results in weaker regularization. A solver is an optimization algorithm used to optimize the loss function. The “Newton-Conjugate Gradient,” “Limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno,” “Stochastic Average Gradient Descent,” and “Stochastic Average Gradient Augmented” were considered for solver parameters.

Feature importance in perceived pain severity prediction

We calculated feature importance using permutation importance to assess each fNIRS feature’s contribution to model performance. This method assesses the change in model accuracy when each feature’s values are randomly shuffled (10 repetitions in this case). Larger drops in accuracy indicate a higher importance of the feature for the model. The average importance and standard deviation were reported across leave-one-participant-out iterations.

Assessment of the classification model’s performance

The performance of the classification model was assessed by using several performance assessment metrics:

-

Precision: Indicates the accuracy of positive predictions, calculated as the ratio of true positives (TP) to the total predicted positives (TP+false positives (FP)).

-

Recall (sensitivity): Measures the model’s ability to identify actual positives, calculated as the ratio of TP to the sum of TP and false negatives (FN).

-

Accuracy: Represents the overall proportion of correctly classified samples out of the total number of samples.

-

F1-score: Harmonizes precision and recall, particularly valuable in unbalanced classes, with values ranging from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate better performance.

To provide a more detailed view of actual versus predicted classes, the confusion matrix was also provided, showing correct and incorrect predictions for each class.

Assessment of the effect of the VR in pain relief and fNIRS functional connectivity features

Each patient in Group B assessed its perceived pain severity prior to and following the VR effect. We used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess statistically significant changes in perceived pain scores and individual fNIRS features before and after the VR intervention, as they were not normally distributed according to the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Significant changes are presented alongside p-values, with heat maps visualizing the difference between the average functional connectivity for HbO and HbR across 41 participants before VR and after VR for features that significantly changed due to VR. These heat maps illustrate the fNIRS features affected by VR.

To account for interactions and redundancies among features and gain a comprehensive understanding of feature changes after VR, we developed a logistic regression model to classify before and after VR conditions. By using binary logistic regression and RFECV feature selection method, we could determine which features are important in classifying two conditions: before VR (class 1) and after VR (class 2). The impact of VR on functional connectivity features was explored using binary logistic regression analysis and the scikit-learn toolbox in Python 3.7. The dataset related to VR effect included 1892 functional connectivity features, extracted from rs-fNIRS data for 41 participants both before and after VR (Group B). The analysis aimed to differentiate between before and after VR conditions, which were coded as class 1 and class 2, respectively, representing a binary classification task. The model training and development approach was similar to the method outlined in the “Classification of perceived pain severity” section.

Subsequently, the model was re-initialized and fitted with the optimally tuned parameters to facilitate a more comprehensive model performance assessment using all samples.

Assessment of the clinical importance of VR in pain relief

The percentage of pain reduction was determined by first calculating the difference in pain scores before and after the VR intervention, then dividing this difference by the pain score before the VR intervention. This product was subsequently multiplied by 100 to obtain the percentage. The percentage of patients achieving 30% pain reduction (i.e., the clinical benchmark for meaningful pain relief54) was calculated. The study emphasizes translating statistical results into practical benefits for patients, aiming to provide clinically relevant information.

Results

The ages and gender distribution of participants in classes 1 to 3 are as follows: 57 ± 15.5 years (43 male samples , 17 female samples, 1 transgender sample), 62 ± 9.9 years (33 male samples, 10 female samples), and 61 ± 10.6 years (22 male samples, 3 female samples), respectively. The Body Mass Index (BMI) values for participants in these classes are 25.54 ± 7.45, 28.68 ± 7.59, and 27.37 ± 5.83, respectively. The pain severity of participants in Group A was zero, as they are healthy individuals. For Group B, the pain scores are reported as the mean ± standard deviation: before VR (4 ± 2.01) and after VR (2 ± 1.59). For Group C, the pain scores are reported as the mean ± standard deviation: 5 ± 2.7.

Classification of perceived pain severity

Fifteen features were selected and used in the model. Validation accuracy, averaged over all cross-validation steps, nested within leave-one-participant-out, was 82% ± 1.8%. Confusion matrix was created using the actual and predicted labels for the test samples, with each participant’s data held out as the test set in turn. This procedure was repeated for all participants. Figure 5A,B shows the confusion matrix and its modified version with accuracy percentages for the MLR model in classifying pain severity levels in test samples. The corresponding classification model’s performance metrics are shown in Table 1.

A confusion matrix for classifying perceived pain severity levels in 129 test samples was obtained by applying the leave-one-participant-out cross-validation technique. This figure illustrates the performance of the MLR model in classifying pain severity into three classes: class 1 (no pain or mild pain), class 2 (moderate pain), and class 3 (severe pain). Panel A displays the confusion matrix, which shows the actual versus predicted labels for the test samples. Panel B shows a confusion matrix with percentages.

The model achieved a prediction accuracy of 74%, indicating its reliability in clinical settings for pain management strategies. Feature importance results are presented in Fig. 6.

Normalized mean and standard deviation of permutation feature importance for predicting perceived pain severity. Each feature represents functional connectivity between channel pairs (Ch) associated with either HbO or HbR signals. Channels 1–24 are located in the prefrontal cortex, channels 25–29 in the right parietal lobe, channels 30–39 in the superior frontal gyrus, and channels 40–44 in the left parietal lobe.

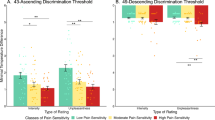

Assessment of virtual reality’s effect on perceived pain severity

Figure 7 shows the perceived pain severity values before and after VR. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test results indicated a significant decrease in perceived pain severity after VR (P < 0.001).

A substantial number of patients, 75.61%, achieved pain relief exceeding the 30% pain threshold (i.e., clinically significant pain relief threshold), suggesting that the VR was effective in relieving the participants’ perceived pain (Fig. 8).

Investigating the effect of VR on fNIRS functional connectivity features

We applied the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to each feature (i.e., functional connectivity between pairs of fNIRS channels) before and after VR and created heat maps to display the resulting p-values (Fig. 9).

Wilcoxon signed-rank test results for functional connectivity features (between fNIRS channels) before and after VR intervention. (A) P-values for HbO functional connectivity features; (B) P-values for HbR functional connectivity features; (C) P-values of statistically significant changes in HbO functional connectivity features (P < 0.05); (D) P-values of statistically significant changes in HbR functional connectivity features (P < 0.05) across 41 participants before VR and after VR for features that significantly changed due to VR.

Notable findings include significant functional connectivity changes in several channel pairs, as evidenced by P-values lower than 0.05 in multiple channel pairs. For example, the fNIRS functional connectivity between channels 17 and 11 (located in the prefrontal cortex) for HbO signals showed a significant change in brain connectivity (P = 0.001) due to the VR effect.

Table 2 presents the fNIRS features selected using RFECV, which assesses feature importance based on their contribution to the model’s predictive performance, for classifying conditions before and after VR.

Furthermore, the binary classification model achieved a validation classification accuracy of 82% ± 3%, determined using stratified 5-fold cross-validation repeated five times, and a test classification accuracy of 79% with leave-one-participant-out cross-validation. This table presents the estimated relationship between the presence of the VR intervention and affected fNIRS functional connectivity across channel pairs, with data describing the estimated coefficient of this association and its statistical significance (P-value) for each feature. Notable findings include significant functional connectivity changes in several channel pairs (P-values lower than 0.05). For example, the fNIRS functional connectivity between channels 5 and 20, both located in the prefrontal cortex, showed a significant change in HbR functional connectivity due to the VR intervention.

Discussion

The objectives of this study are to (1) classify perceived pain severity in cancer patients into no/mild, moderate, and severe categories using rs-fNIRS features, and (2) assess VR effects in cancer pain management.

Classification of perceived pain severity

The performance of the MLR model in classifying pain severity across the test samples demonstrates the model’s reliability for pain management in clinical settings, where the accurate classification of pain levels can guide personalized treatment plans. The feature importance analysis offers understandings about the key predictors of pain severity levels. Identifying neural markers linked to varying pain severity levels enables more precise, individualized interventions that align with each person’s unique pain experience.

Changes in functional connectivity among channel pairs in prefrontal cortex are indicative of neural communication changes linked to pain severity55. The prefrontal cortex plays a significant role in pain processing37. The connections of the prefrontal cortex to other regions of the cerebral neocortex and other brain regions are essential in this process. Changes in neurotransmitters within the prefrontal cortex are also linked to pain processing55. Our findings indicated that the fNIRS functional connectivity features between various channels within the prefrontal and parietal cortices are important for classifying perceived pain severity levels. This observation aligns with prior research demonstrating the critical roles of these brain regions in cognitive and affective aspects of pain processing56. Cognitive factors such as attention, expectancy, and appraisal can amplify or diminish pain perception. For example, expecting a stimulus to be painful can heighten the pain experience, whereas positive appraisals can mitigate it57,58. Similarly, emotional states play a key role, with negative emotions often intensifying pain perception and positive emotions reducing it56. These findings suggest that the cognitive and emotional components of pain processing are key contributors to the variability in perceived pain levels.

Channels representing the parietal cortex also played a key role in classifying perceived pain severity levels, underscoring their involvement in the sensory-discriminative aspect of pain processing. This finding aligns with state-of-the-art research indicating that the parietal cortex is crucial for the sensory-discriminative aspects of pain processing, including spatial awareness and the differentiation of sensory characteristics of pain59. Previous research indicated that increased activity in the parietal cortex correlates with the processing of pain perception and recognition of somatosensory stimuli, particularly in cases of mild to moderate pain60,61. Structural and functional changes in the parietal cortex have been observed in individuals experiencing chronic pain, highlighting its significance in the broader network of brain regions responsible for pain perception62.

Functional connectivity of both HbO and HbR signals played key roles in classifying perceived pain severity in cancer patients. This finding suggests that both oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin dynamics are linked to the neural mechanisms underlying pain perception. Specifically, the involvement of HbO signals may reflect increased neuronal activation and oxygen delivery in brain regions associated with pain processing, such as the prefrontal and parietal cortices. Similarly, HbR signals, indicative oxygen utilization and metabolic coupling, may highlight the efficiency of neural activity and its relationship to pain intensity. These results align with previous studies emphasizing the importance of hemodynamic responses in cognitive and emotional modulation of pain49,50,51,52. The dual contribution of HbO and HbR functional connectivity underscores the complex interplay between vascular and neural activity in the brain’s pain processing pathways.

While fNIRS is widely used for pain assessment, modalities such as EEG have recently gained increasing attention. Both modalities provide understanding about brain activity associated with pain perception, albeit through different mechanisms. EEG has been shown to reflect changes in brain oscillations related to pain states, with studies indicating alterations in alpha and beta power during painful stimuli63,64. While EEG can indicate changes in brain activity associated with pain, the relationship between EEG changes and clinical pain outcomes is complex and not fully established63. Conversely, fNIRS has emerged as a valuable tool for assessing main pain responses, particularly in clinical settings where traditional imaging methods may be impractical. Research indicates that fNIRS effectively captures hemodynamic changes in the prefrontal cortex and other regions during pain experiences, demonstrating its utility in monitoring pain levels and responses to analgesic interventions65,66,67. However, the limitations of fNIRS, such as its reduced ability to detect deeper brain structures, should be acknowledged66. The integration of these technologies could enhance our understanding of pain mechanisms in cancer patients, providing a comprehensive approach to pain assessment and management.

Assessment of the VR effect in pain relief

In clinical settings, a pain reduction of 30% or more is widely regarded as a meaningful benchmark, often correlating with significant improvements in a patient’s quality of life, functionality, and overall well-being54,68. This threshold is supported by evidence showing that such reductions are associated with noticeable relief, enabling patients to better perform daily activities and experience increased comfort69,70. This metric is particularly crucial for chronic pain sufferers, whose lives are often severely disrupted by persistent pain. In addition to its clinical importance, the 30% pain reduction is widely used as a practical threshold in clinical trials assessing the efficacy of pain management therapies, including pharmacological treatments, physical therapy, and cognitive-behavioral interventions70,71. For healthcare providers, this benchmark serves as a practical target for tailoring interventions based on patient-reported outcomes, ensuring a patient-centered approach to pain management69.

In the current study, for Group B, the significant reduction in pain scores after VR intervention demonstrates VR’s potential as a non-pharmacological analgesic tool for cancer patients experiencing pain. The substantial reduction post-intervention suggests that VR alleviates perceived pain in cancer patients, supporting the hypothesis that VR could be a practical complementary to traditional pain management methods. The finding also suggests that VR has the potential to serve as a cost-effective and scalable approach for pain relief in clinical settings, especially among cancer patients who may experience high levels of pain.

The study findings align with previous studies that highlight VR’s impact on pain perception. VR has been shown to alleviate cancer pain perception by diverting attention and engaging patients in immersive experiences72. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that VR significantly reduced pain among breast cancer patients, highlighting its effect as a distraction technique73. Additionally, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that VR interventions led to significant improvements in pain, anxiety, and quality of life for cancer patients, supporting the use of VR as an adjunctive therapy in cancer rehabilitation74.

Effect of VR on fNIRS functional connectivity features

Identified changes in functional connectivity patterns indicate VR’s impact on neural communication across brain regions related to pain perception. The significant changes observed between channels located in the prefrontal cortex for HbO signals, may point to specific neural pathways involved in modulating pain perception during VR intervention. These findings align with the hypothesis that VR’s impact on the brain’s functional connectivity may contribute to pain relief through altered connectivity in pain-related neural circuits. The observed changes could potentially facilitate optimizing VR settings to target connectivity features that yield maximum pain relief for individual patients.

Changes in functional connectivity within the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in cognitive functions and emotional regulation75,76, suggest that VR may modulate the cognitive and emotional components of pain. The observed significant changes in functional connectivity between brain regions (e.g., between channels located in the prefrontal cortex and the superior frontal gyrus) may indicate a disruption or alteration in the usual pain processing pathways due to the VR intervention. These results show VR’s role in modulating neural networks that process the cognitive-emotional aspects and the sensory dimensions of pain, which is aligned with the findings in previous studies.

VR is an effective pain management tool, primarily due to its immersive nature, which captures the patient’s attention and creates a strong distraction from pain77. This distraction mechanism shifts cognitive resources away from pain processing, thereby reducing the perceived intensity of pain. Cognitive and affective modulation play key role in VR-induced pain relief. For instance, the positive emotional states elicited by engaging VR environments could further reduce pain perception by counteracting negative emotions often associated with pain56,78,79,80. Previous research has shown that VR not only distracts patients from pain but also induces psychological effects that contribute to pain relief, such as relaxation and emotional engagement81. Furthermore, VR has been found to be more effective than traditional distraction methods, such as 2D videos, in attenuating pain signals through multisensory awareness82. Additionally, immersive VR experiences may influence cognitive appraisals of pain, reframing the experience in a way that reduces its perceived severity. This interplay between distraction, emotional states, and cognitive appraisals highlights the multifaceted mechanisms underlying VR pain relief.

Functional connectivity of both HbO and HbR channels in several brain regions significantly changed following the VR intervention. This finding suggests that HbO and HbR dynamics are involved in the neural mechanisms underlying VR-induced pain relief. Specifically, changes in HbO functional connectivity may reflect increased neural activation and oxygen delivery in regions associated with attention, emotion regulation, and sensory processing, which are key to the immersive and distracting effects of VR. Similarly, alterations in HbR connectivity may indicate modifications in oxygen utilization and metabolic efficiency, highlighting the role of neurovascular coupling in the brain’s response to VR.

Classification of Pre- and Post-VR conditions using functional connectivity

The reasonably high accuracy achieved in distinguishing pre- and post-VR states further supports the impact of VR on the brain’s functional connectivity, particularly in regions associated with pain perception and processing. The key features identified in this model provide perspectives on which neural connections are important in distinguishing before and after VR states. For instance, the significant coherence changes between channels located in the prefrontal cortex for HbR signals highlights VR’s role in modulating specific functional connectivity within this brain region.

The selected features illustrate potential biomarkers for tracking changes in brain functional connectivity in response to VR interventions. The relatively high classification accuracy also suggests that these fNIRS-based functional connectivity changes could be used in future clinical applications to assess the effect of VR in real-time or as an adjunct in therapeutic settings. This understanding paves the way for exploring VR-based pain management further, potentially enabling personalized VR interventions tailored to the specific functional connectivity profiles of patients.

Strength of the study and implications

This study used fNIRS functional connectivity features and MLR to classify perceived pain severity in cancer patients into three levels (no pain or mild pain, moderate, or severe). This offers a tool for cancer pain management with relatively high accuracy. The leave-one-participant-out cross-validation showed strong test accuracy, demonstrating its ability to generalize to new participants, crucial for clinical settings with diverse patient variability.

Most existing studies in the field of pain level classification using fNIRS and machine learning focus on pain induced by pressure or thermal stimuli14,47,83 (Table 3). Those studies demonstrate the effect of fNIRS data in identifying patterns associated with varying levels of pain severity. However, these approaches face greater challenges in clinical settings, particularly in accurately classifying the intensity of natural pain experienced by cancer patients. The present study marks a significant advancement in the development of objective methods for pain severity prediction among cancer patients.

Additionally, study findings highlight VR’s potential as a useful, non-invasive pain management tool, capable of inducing significant reductions in perceived pain severity among cancer patients. The model’s high accuracy and the significant changes in fNIRS connectivity patterns suggest that VR affects specific neural circuits associated with pain perception. This has important implications for developing non-pharmacological pain management strategies and contributes to the broader field of neuro-modulatory therapies. Future research could focus on refining the functional connectivity features identified, potentially leading to tailored VR interventions based on individual brain’s functional connectivity profiles.

Moreover, exploring the underlying mechanisms of VR’s impact on functional connectivity could offer new knowledge about the neural mechanisms of pain perception, potentially leading to breakthroughs in pain management for clinical populations.

Limitations of the study

The study’s results, while promising, may have limited generalizability due to reliance on patients from a single pain clinic. Broader studies with diverse cohorts and various VR programs, and examinations of VR’s long-term effects on brain connectivity, are needed for a more comprehensive investigation. We acknowledge that the study is limited due to the absence of a control or sham procedure. Consideration of the placebo effect would be useful in VR treatment studies to assess the effect of VR interventions more accurately; while the present study did not address this, a placebo effect should be considered in future research. We acknowledge that this study is limited by the fact that fNIRS primarily measures activity in surface regions of the brain, whereas key regions involved in pain perception, such as the cingulate cortex, insula, and parietal operculum, are located deeper within the hemisphere. We acknowledge that the groups in this study were not matched for age, sex, or BMI. Additionally, we did not account for the education level factor.

Future studies should aim for models specific to each pain type (cancer-related or treatment-related), which may enhance understanding of how pain is processed and the prediction accuracy in cancer patients. Studies could also examine the long-term effects of VR on functional connectivity to determine whether repeated sessions produce cumulative benefits for pain relief.

Conclusion

The developed pain severity classification model, developed in this study, shows promise for potential applications of fNIRS and machine learning in clinical pain management, where reliable, automated pain assessment can support more personalized and efficient care strategies.

Our study demonstrates the effect of VR in reducing perceived pain severity among cancer patients, highlighting VR’s potential as a non-invasive tool and non-pharmacological method for pain management. The significant changes in functional connectivity observed after VR intervention suggest that VR may influence pain perception through modulation of pain-related neural circuits.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [SBS] upon reasonable request.

Code availability

No custom code or mathematical algorithm was developed for this study.

References

Zaza, C. & Baine, N. Cancer pain and psychosocial factors: A critical review of the literature. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 24(5), 526–542 (2002).

Tang, S. et al. Trends in quality of end-of-life care for Taiwanese cancer patients who died in 2000–2006. Ann. Oncol. 20(2), 343–348 (2009).

Goswami, S., et al., Pain management in oncology. In Cancer diagnostics and therapeutics: Current trends, challenges, and future perspectives. 333-373 (Springer, 2022).

Breitbart, W. et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. Jama 284(22), 2907–2911 (2000).

Zaorsky, N. G. et al. Suicide among cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 207 (2019).

Fang, C.-K. et al. A correlational study of suicidal ideation with psychological distress, depression, and demoralization in patients with cancer. Supportive Care Cancer 22, 3165–3174 (2014).

Sharma, V. & de Leon-Casasola, O. Cancer pain. In Practical management of pain (eds Benzon, H. T. et al.) 335–345 (Mosby (Elsevier), 2014).

Swarm, R. A. et al. Adult cancer pain. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 11(8), 992–1022 (2013).

Bendinger, T. & Plunkett, N. Measurement in pain medicine. Bja Educat. 16(9), 310–315 (2016).

Sailors, M. H. et al. Validating the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) for use in patients with ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncol. 130(2), 323–328 (2013).

Horgas, A.L., Elliott, A.F. & Marsiske, M. Pain assessment in persons with dementia: Relationship between self‐report and behavioral observation. J. American Geriatr. Soc. 57(1), 126–132 (2009).

Herr, K., Coyne, P.J., McCaffery, M., Manworren, R. & Merkel, S. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain manage. nurs. 12(4), 230–250 (2011).

Melzack, R. The McGill pain questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1(3), 277–299 (1975).

Lopez-Martinez, D., et al. Pain Detection with FNIRS-measured brain signals: A personalized machine learning approach using the wavelet transform and Bayesian hierarchical modeling with dirichlet process priors. In 2019 8th international conference on affective computing and intelligent interaction workshops and demos (ACIIW). (IEEE, 2019).

Niu, H. & He, Y. Resting-state functional brain connectivity: Lessons from functional near-infrared spectroscopy. The Neuroscientist 20(2), 173–188 (2014).

Fernandez Rojas, R., Huang, X. & Ou, K.-L. A machine learning approach for the identification of a biomarker of human pain using fNIRS. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 5645 (2019).

Rojas, R.F., et al. FNIRS approach to pain assessment for non-verbal patients. In Neural Information Processing: 24th International Conference, ICONIP 2017, Guangzhou, China, November 14–18, 2017, Proceedings, Part IV 24. (Springer, 2017).

Sharini, H. et al. Identification of the pain process by cold stimulation: Using dynamic causal modeling of effective connectivity in functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). IRBM 40(2), 86–94 (2019).

Nie, H., Graven-Nielsen, T. & Arendt-Nielsen, L. Spatial and temporal summation of pain evoked by mechanical pressure stimulation. Eur. J. Pain 13(6), 592–599 (2009).

Johnson, M. H. How does distraction work in the management of pain?. Curr. Pain Headache Rep.9, 90–95 (2005).

Malloy, K. M. & Milling, L. S. The effectiveness of virtual reality distraction for pain reduction: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30(8), 1011–1018 (2010).

Yen, C. T. & Lu, P. L. Thalamus and pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 51(2), 73–80 (2013).

Catani, M., Dell’Acqua, F. & De Schotten, M.T. A revised limbic system model for memory, emotion and behaviour. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37(8), 1724–1737 (2013).

Jensen, K. B. et al. Brain activations during pain: A neuroimaging meta-analysis of patients with pain and healthy controls. Pain 157(6), 1279–1286 (2016).

Xu, A. et al. Convergent neural representations of experimentally-induced acute pain in healthy volunteers: A large-scale fMRI meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 112, 300–323 (2020).

Favilla, S. et al. Ranking brain areas encoding the perceived level of pain from fMRI data. Neuroimage 90, 153–162 (2014).

Vogt, B. A. Pain and emotion interactions in subregions of the cingulate gyrus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6(7), 533–544 (2005).

Craig, A. D. A new view of pain as a homeostatic emotion. Trends Neurosci. 26(6), 303–307 (2003).

Apkarian, A. V. et al. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J. Pain 9(4), 463–484 (2005).

Apkarian, A. V., Baliki, M. N. & Geha, P. Y. Towards a theory of chronic pain. Progr. Neurobiol. 87(2), 81–97 (2009).

Scholkmann, F. et al. A review on continuous wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging instrumentation and methodology. Neuroimage 85, 6–27 (2014).

Henry, J. C. Electroencephalography: Basic principles, clinical applications, and related fields. Neurology 67(11), 2092–2092-a (2006).

Logothetis, N. K. What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature 453(7197), 869–878 (2008).

Raichle, M. E. A brief history of human brain mapping. Trends Neurosci. 32(2), 118–126 (2009).

Baillet, S. Magnetoencephalography for brain electrophysiology and imaging. Nat. Neurosci. 20(3), 327–339 (2017).

Symonds, L. L. et al. Right-lateralized pain processing in the human cortex: An FMRI study. J. Neurophysiol. 95(6), 3823–3830 (2006).

Ong, W.-Y., Stohler, C. S. & Herr, D. R. Role of the prefrontal cortex in pain processing. Mol. Neurobiol. 56(2), 1137–1166 (2019).

Khera, T. & Rangasamy, V. Cognition and pain: A review. Front. Psychol. 12, 1819 (2021).

Spisak, T. et al. Pain-free resting-state functional brain connectivity predicts individual pain sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 187 (2020).

Lawson, S. L. et al. Pediatric pain assessment in the emergency department: Patient and caregiver agreement using the Wong-Baker FACES and the Faces Pain Scale-Revised. Pediatric Emerg. Care 37(12), e950–e954 (2021).

Kostović, I. & Jovanov-Milošević, N. The development of cerebral connections during the first 20–45 weeks’ gestation. In seminars in fetal and neonatal medicine. (Elsevier, 2006).

Shi, Y., et al., Brain network response to acupuncture stimuli in experimental acute low back pain: An fMRI study. Evid. -Based Complementary Alternative Med., 2015, (2015).

Wang, J., Dong, Q. & Niu, H. The minimum resting-state fNIRS imaging duration for accurate and stable mapping of brain connectivity network in children. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 6461 (2017).

ecovr. Oceania VR [Virtual reality experience]. Available from: https://www.ecovr.world/oceaniavr.

Santosa, H. et al. The NIRS brain AnalyzIR toolbox. Algorithms 11(5), 73 (2018).

Novi, S. L., Rodrigues, R. B. & Mesquita, R. C. Resting state connectivity patterns with near-infrared spectroscopy data of the whole head. Biomed. Opt. Exp. 7(7), 2524–2537 (2016).

Fernandez Rojas, R., Huang, X. & Ou, K.-L. Toward a functional near-infrared spectroscopy-based monitoring of pain assessment for nonverbal patients. J. Biomed. Opt. 22(10), 106013–106013 (2017).

Buxton, R. B. et al. Modeling the hemodynamic response to brain activation. Neuroimage 23, S220–S233 (2004).

Attwell, D. & Iadecola, C. The neural basis of functional brain imaging signals. Trends Neurosci. 25(12), 621–625 (2002).

Hernandez-Martin, E. et al. Diffuse optical tomography provides a high sensitivity at the sensory-motor Gyri: A functional region of interest approach. Appl. Sci. 13(23), 12686 (2023).

Kinder, K. T. et al. Systematic review of fNIRS studies reveals inconsistent chromophore data reporting practices. Neurophotonics 9(4), 040601–040601 (2022).

Bartnik-Olson, B. L. et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping as a measure of cerebral oxygenation in neonatal piglets. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 42(5), 891–900 (2022).

Hanley, M. A. et al. Pain interference in persons with spinal cord injury: Classification of mild, moderate, and severe pain. J. Pain 7(2), 129–133 (2006).

Farrar, J. T. et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 94(2), 149–158 (2001).

Ong, W.-Y., Stohler, C. S. & Herr, D. R. Role of the prefrontal cortex in pain processing. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 1137–1166 (2019).

Peters, M. L. Emotional and cognitive influences on pain experience. Pain Psychiatric Disord. 30, 138–152 (2015).

Crombez, G. et al. Hypervigilance to pain in fibromyalgia: The mediating role of pain intensity and catastrophic thinking about pain. Clin. J. Pain 20(2), 98–102 (2004).

Peters, M. L. & Crombez, G. Assessment of attention to pain using handheld computer diaries. S110-S120 (Blackwell Publishing Inc Malden, USA, 2007)

Duncan, G. H., Albanese, M. C. & Khoshnejad, M. PET and fMRI Imaging in Parietal Cortex (SI, SII, Inferior Parietal Cortex BA40). In Encyclopedia of Pain (eds Gebhart, G. F. & Schmidt, R. F.) 2865–2870 (Springer, 2013).

Bagheri, Z. et al. Differential cortical oscillatory patterns in amputees with and without phantom limb pain. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 14(2), 171 (2023).

Kumar, P. & Singh, S. Comparative study of outcome in epidural bupivacaine with buprenorphine and bupivacaine with fentanyl in lower limb surgeries. IJMA 3(1), 106–113 (2020).

Salazar-Méndez, J. et al. Structural and functional brain changes in people with knee osteoarthritis: A scoping review. PeerJ 11, e16003 (2023).

Mathew, J. et al. Is there a difference in EEG characteristics in acute, chronic, and experimentally induced musculoskeletal pain states? A systematic review. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 55(1), 101–120 (2024).

Zis, P. et al. EEG recordings as biomarkers of pain perception: Where do we stand and where to go?. Pain Therapy 11(2), 369–380 (2022).

Pollonini, L. et al. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy to assess central pain responses in a nonpharmacologic treatment trial of osteoarthritis. J. Neuroimaging 30(6), 808–814 (2020).

Hu, X.-S., Nascimento, T. D. & DaSilva, A. F. Shedding light on pain for the clinic: A comprehensive review of using functional near-infrared spectroscopy to monitor its process in the brain. Pain 162(12), 2805–2820 (2021).

Hall, M. et al. Pain induced changes in brain oxyhemoglobin: A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional NIRS studies. Pain Med. 22(6), 1399–1410 (2021).

Moore, R. A., Straube, S. & Aldington, D. Pain measures and cut-offs-’no worse than mild pain’as a simple, universal outcome. Anaesthesia 68(4), 400 (2013).

Turk, D. C. & Dworkin, R. H. What should be the core outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials?. Arthritis Res. Ther. 6, 1–4 (2004).

Rowbotham, M. C. What is a ‘clinically meaningful’reduction in pain?. Pain 94(2), 131–132 (2001).

Dworkin, R. H. et al. Considerations for improving assay sensitivity in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 153(6), 1148–1158 (2012).

Tantri, I. N. et al. The role of virtual reality in cancer pain management: A systematic literature review. Bioscientia Medicina: J. Biomed. Transl. Res. 7(1), 3018–3023 (2023).

Mohammad, E. B. & Ahmad, M. Virtual reality as a distraction technique for pain and anxiety among patients with breast cancer: A randomized control trial. Palliat. Supportive Care 17(1), 29–34 (2019).

Hao, J. et al. Effects of virtual reality on physical, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in cancer rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Supportive Care Cancer 31(2), 112 (2023).

Ray, R. D. & Zald, D. H. Anatomical insights into the interaction of emotion and cognition in the prefrontal cortex. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36(1), 479–501 (2012).

Friedman, N. P. & Robbins, T. W. The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology 47(1), 72–89 (2022).

Droc, G. et al. Postoperative cognitive impairment and pain perception after abdominal surgery—Could immersive virtual reality bring more? A clinical approach. Medicina 59(11), 2034 (2023).

Ghobadi, A. et al. The effect of virtual reality on reducing patients’ anxiety and pain during dental implant surgery. BMC Oral Health 24(1), 186 (2024).

He, Z. H. et al. The effects of virtual reality technology on reducing pain in wound care: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Int. Wound J. 19(7), 1810–1820 (2022).

Wong, K. P., Tse, M. M. Y. & Qin, J. Effectiveness of virtual reality-based interventions for managing chronic pain on pain reduction, anxiety, depression and mood: A systematic review. In Healthcare. (MDPI, 2022).

Funao, H. et al. Virtual reality applied to home-visit rehabilitation for hemiplegic shoulder pain in a stroke patient: A case report. J. Rural Med. 16(3), 174–178 (2021).

Pandrangi, V. C. et al. Effect of virtual reality on pain management and opioid use among hospitalized patients after head and neck surgery: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 148(8), 724–730 (2022).

Rojas, R. F., et al. Pain assessment based on fnirs using bi-lstm rnns. In 2021 10th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER). (IEEE, 2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mehdi Seilanian Toussi, MD, the Intelligent Cancer Care Laboratory, Department of Urology, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, NY, for his contribution to data recording. Editorial assistance for this publication was provided by Roswell Park’s Scientific Editing and Research Communications Core (SERCC) Resource, which is supported by a National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center Support Grant (grant no. NCI P30CA016056).

Funding

This research was supported by Health Research Inc. (HRI) through its in-house research and development program, specifically the Faculty Recruitment Startup at the Center for Surgical Innovation (PI: Somayeh Besharat Shafiei). No award number was provided.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.S. drafted the manuscript and played a key role in the conceptualization and design of the study, data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of the results, and securing funding. S.S. made substantial contributions to the design of the study, analysis, and interpretation of the results, and substantially revised the draft. O.D. played a key role in facilitating data acquisition and patient recruitment, interpretation of the results, and significantly contributed to revising the draft. B. P. and M. B. M. made significant contributions to patient recruitment facilitation. All authors have thoroughly reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center (I-1720121; PI: Somayeh B Shafiei; Date of approval: 10/17/2021).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shafiei, S.B., Shadpour, S., Pangburn, B. et al. Pain classification using functional near infrared spectroscopy and assessment of virtual reality effects in cancer pain management. Sci Rep 15, 8954 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93678-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93678-y

This article is cited by

-

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy for the detection of fear using parameterized quantum circuits

Scientific Reports (2025)