Abstract

This study systematically analyzes the land use changes in Changsha City from 2000 to 2023. Three classification models—Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT), and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) were employed to evaluate the accuracy of land use classification. The RF model, with an accuracy of 95.78%, outperformed the others, demonstrating its robustness and generalization ability in handling complex land use classification tasks. The study further conducted a spatiotemporal analysis of urban construction land expansion, identified key driving forces behind urbanization in Changsha. Results indicate that the construction land area expanded nearly threefold, from 563.82 km² in 2000 to 1628.20 km² in 2023, with the most significant growth occurring between 2010 and 2015. This rapid expansion was largely driven by China’s “New Urbanization” policy and population growth. Additionally, 12 key factors influencing land use change in Changsha was analyzed, including slope, soil salinity, annual mean temperature, leaf area index, soil moisture, aerosols, aspect, nighttime light index (X8), DEM, population density (X10), vegetation cover, and annual precipitation. Univariate and interaction detection analyses revealed that the nighttime light index (X8) and population density (X10) were the most significant drivers of construction land expansion, consistently exhibiting high q-values across all years. In contrast, natural factors, such as slope (X1) and aerosols (X6), had a lesser impact on land use change, although their influence has gradually increased over time. This is particularly evident in the growing role of annual precipitation (X12) and leaf area index (X4) in influencing ecosystem and vegetation recovery. The study also simulated construction land expansion trends for 2030 under three different scenarios. In the natural development scenario, construction land area is projected to expand to 1920.65 km², reflecting unregulated expansion of urbanization. Under the farmland protection scenario, the area will grow to 1826.32 km², indicating the effectiveness of policy interventions in preserving agricultural land. The ecological control scenario, however, predicts a limited expansion to 1702.66 km², underscoring the importance of ecological protection policies in curbing uncontrolled urban sprawl. This research provides a comprehensive understanding of the driving mechanisms and evolutionary patterns of construction land use change in Changsha. It highlights the significant pressure that urbanization, particularly anthropogenic factors, has placed on land resources. It also demonstrates that policy regulation, particularly through ecological protection measures, can effectively mitigate this expansion trend. The findings offer valuable insights for land use planning and policy formulation in Changsha, underscoring the importance of balancing economic development with ecological preservation to achieve sustainable urban growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global urbanization accelerates, the expansion of urban construction land has emerged as a critical driver of both socio-economic development and environmental change1,2. In China, the rapid urbanization process has significantly transformed land use patterns, posing substantial challenges to urban planning and sustainable development. Changsha, a rapidly growing city in central China, exemplifies these dynamics. The expansion of construction land in Changsha not only influences the rational allocation of land resources but also has profound implications for ecosystem services3,4. Thus, accurately predicting and simulating the spatial patterns of construction land expansion is essential for optimizing land use structures and formulating sustainable development strategies.

The implications of construction land expansion extend beyond land resource management, affecting the ecological environment and urban development planning. To address these challenges, various modeling approaches have been developed to simulate and predict urban expansion, provide scientific support for urban planning. Commonly used models include Cellular Automata (CA), Markov Chain, and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)5. However, despite advancement of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing technologies, effectively capturing the dynamics of urban construction land within complex spatial environments remains a challenge.

Globally, notable progress has been made in urban land use changes simulation. Verburg and colleagues proposed a geospatial modeling approach for land use change simulation, which has been validated across multiple cities with high accuracy. Simiarly, White and Engelen developed the Cellular Automata model, which integrates urban expansion with environment and policy factors, effectively predicting urban growth in diverse regions. In recent years, the Future Land Use Simulation (FLUS) model, an advanced tool based on Cellular Automata, has gained prominence for simulating urban construction land changes6,7,8. The GeoSOS-FLUS, an extended version of this model, incorporates multi-source data and uncertainty analyses, offering enhanced capabilities to capture the spatiotemporal characteristics of urban expansion.

In China, urban construction land simulation has also been extensively explored, particularly in coastal and economically developed region. For example, Ma Li et al. used the CA-Markov model to simulate construction land expansion in Wuhan, demonstrating the model’s predictive effectiveness. Wang Lei et al. applied the GeoSOS-FLUS model to predict land use changes in the Pearl River Delta urban agglomeration, providing valuable insights into land use planning9. However, research on rapidly developing cities in central China, such as Changsha, remains limited. Existing studies often fail to adequately capture the unique characteristics and environmental impacts of construction land expansion in these regions10.

This study utilizes the GeoSOS-FLUS model, integrating topographical, socio-economic, vegetation, climate, and other factors to simulate and predict the future construction land expansion in Changsha. By constructing a spatiotemporal evolution model, this research aims to analyze the spatial pattern changes in Changsha’s construction land and forecast future trends, offering valuable insights for urban planning and policy-making. Compared to traditional models, the GeoSOS-FLUS model demonstrates significant advantages in processing complex spatiotemporal data and addressing uncertainties, enhancing the accuracy and scientific validity of urban expansion simulations11,12,13. Consequently, this study not only contributes to improving the rationality of land use planning in Changsha but also offers a reference for other rapidly developing cities in central China14.

Data and methods

Study area

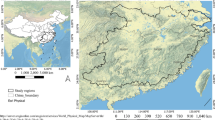

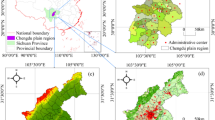

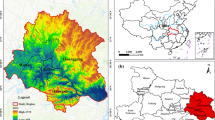

Changsha, located in central region of China, lies in the northeastern part of Hunan Province, with geographic coordinates spanning 27°51′ to 28°40′ N latitude and 111°53′ to 114°15′ E longitude (Fig. 1)15. As the capital of Hunan Province, Changsha plays a pivotal role in the urban agglomeration along the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and is recognized as one of China’s historical and cultural cities16. The city encompasses a total area of approximately 11,819 square kilometers and administers governs six districts, three county-level cities, and one county.

According to the data from the seventh national census, Changsha’s permanent population has exceeded 10 million. In recent years, the city’s rapid urbanization has transformed it into a key economic, cultural, and transportation hub in China. The topography of Changsha is characterized by a combination of hilly and flat terrains, with mountainous regions in the northwest and the alluvial plains of the Xiang River in the southeast. Flowing from south to north, the Xiang River serves not only as a vital natural boundary but also as a scenic axis, shaping the city’s urban development17.

Changsha’s climate is classified as a subtropical monsoon climate, featuring an average annual temperature of approximately 17 °C. The region experiences abundant rainfall, with an average annual precipitation of about 1400 mm, conditions that are conducive to agricultural production and ecological preservation. These favorable climatic and geographical attributes have historically supported Changsha’s economic growth and environmental sustainability.

In recent years, the city’s urban functions have been continuously enhanced, and its industrial structure has undergone significant optimization, establishing Changsha as a major economic growth pole in central China. However, the rising demand for construction land driven by rapid urbanization has exacerbated land resource tensions and conflicts over land use18. As such, simulating and forecasting land use changes in Changsha is critical to providing scientific support for urban planning authorities. These efforts will facilitate the optimal allocation of land resources and contribute to promoting sustainable urban development.

Location map of Changsha City (approval number: [GS(2019)3333]). Note: the map was generated by QGIS 3.16 (https://qgis.org/).

Remote sensing data

Landsat data

The primary remote sensing data used in this study consists of Landsat series imagery. The Landsat satellites provide long-term, moderate-resolution multispectral remote sensing images, which are widely applied in land use change detection, urban expansion, and ecological environment monitoring. For this experiment, Landsat 5 and Landsat 8 images were selected, covering the study area of Changsha City19,20. A systematic collection of Landsat images from 2000 to 2023 was conducted, resulting in over 100 scenes that span key periods over the past two decades.

To ensure the accuracy and consistency, the following preprocessing steps were conducted:

Atmospheric Correction: Atmospheric correction was performed using the Landsat Surface Reflectance data products available on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. These products apply the Landsat Ecosystem Disturbance Adaptive Processing System (LEDAPS) and Landsat 8 Surface Reflectance Code (LaSRC) to remove atmospheric distortions, such as aerosols and water vapor.

Geometric correction: All images were geometrically corrected to ensure spatial alignment using the high-quality ground control points provided in the Landsat archive. The images were resampled to a 30-meter resolution to maintain consistency across datasets.

Cloud masking: Preference was given to images with minimal cloud cover. To further minimize cloud interference, the FMask (Function of Mask) algorithm available in GEE was applied. This step accurately identified and masked clouds and their shadows to improve the quality of the final datasets.

Temporal consistency: Given the 16-day temporal resolution of Landsat imagery, all images were reviewed to select those captured during similar phenological stages, ensuring comparability over time.

Quality control: A visual inspection was performed to confirm the removal of significant artifacts such as striping or residual cloud contamination. Images that failed to meet quality standards were excluded from the analysis.

These preprocessing steps ensured the high quality and reliability of the dataset, enabling robust monitoring and analysis of urban land use changes in Changsha City21.

Driving factor data

Based on the calculation principles of the GeoSOS-FLUS model, this study integrates the actual land use conditions in Changsha City with the availability of relevant data. Drawing on research findings on land use change drivers from both domestic and international studies, 12 driving factors influencing land use changes in Changsha for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020, and 2023 were selected. These factors fall into five categories: topographic factors, socioeconomic factors, vegetation factors, climatic factors, and other influencing factors (see Table 1)22,23. Since the spatial resolution of the data from various sources differs, all data were uniformly resampled to a 30-meter resolution to facilitate consistent computational processing.

Among these driving factors, the nighttime light index (X8) and population density (X10) are particularly significant, as they represent key indicators of anthropogenic influences on land use changes. The following sections elaborate on the data sources and preprocessing methods for these two factors. The nighttime light index (X8) was derived from the NPP-VIIRS dataset, provided by the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. This dataset, with an original spatial resolution of 750 m, captures the intensity of artificial lighting at night, serving as a proxy for human activity and urbanization levels. To ensure the reliability of the data, preprocessing steps were conducted to remove noise caused by transient light sources, such as wildfires and fishing fleets. Temporal averaging was applied to generate yearly composite images, reducing the impact of seasonal variations. Finally, the processed data were resampled to a 30-meter resolution to ensure consistency with other driving factors. The resulting nighttime light index data provide a robust measure of urbanization intensity and its spatial distribution, making it a critical factor in analyzing construction land expansion; The population density were obtained from the WorldPop dataset, which offers high-resolution gridded estimates of population distribution. With an initial resolution of 100 m, this dataset was further processed to align with the study’s analytical requirements. First, population data were aggregated to administrative boundaries using a weighted overlay technique, ensuring a more accurate representation of population distribution patterns. Temporal gaps in the dataset were addressed through interpolation, allowing for the generation of consistent population density data across the study years. The resampled 30-meter resolution data enabled seamless integration with other factors, providing an essential measure of human settlement intensity and its role in driving urban land use changes.

By combining these datasets with other driving factors, this study ensures a comprehensive analysis of both anthropogenic and natural influences on land use changes in Changsha. The detailed preprocessing steps and quality control measures applied to the nighttime light index and population density data enhance the robustness and reproducibility of the results.

Land use classification method

RF

In this study, the random forest (RF) algorithm was employed on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform to classify land use in Changsha City. RF is a non-parametric supervised learning algorithm based on an ensemble of decision trees. It achieves classification by constructing multiple decision trees using randomly sampled training data and aggregating their predictions through majority voting. This approach makes RF highly robust to noisy data and irrelevant features while maintaining strong generalization capabilities, especially in high-dimensional datasets24,25,26.

The RF model was configured with the following parameters: 300 trees, a maximum tree depth of 25, a minimum sample split size of 10, a minimum sample size per leaf of 2, and the square root of the total features as the maximum feature subset size. These parameters were selected through iterative experimentation and cross-validation. Increasing the number of trees enhanced classification stability, while the depth limit of 25 balanced accuracy and overfitting risks. Additionally, the square root feature subset reduced model complexity while preserving performance.

The robustness of RF stems from its ensemble approach, which minimizes variance by averaging the predictions of multiple decision trees. This method reduces the risk of overfitting and makes RF less sensitive to noisy data compared to models like Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT). Its ability to handle complex land use classification tasks efficiently makes RF particularly suitable for Changsha’s diverse and high-dimensional land use datasets.

The Random Forest algorithm is an ensemble learning method that achieves classification or regression tasks by constructing a collection of decision trees. In the context of classification, the RF algorithm operates by randomly sampling the training dataset to build multiple classification trees. Each tree makes classification predictions based on the features of the samples, and the final output of the random forest is determined by majority voting among the predictions of all trees. The core formula for the algorithm is as follows:

WhereT1(x), T2(x), … ,Tn(x) represent each decision tree constructed by randomly selecting feature subsets, and f(x) represents the final classification result.

GBDT

Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) is an ensemble learning method that constructs decision trees sequentially, with each tree aiming to correct the errors of its predecessors. Unlike RF, GBDT minimizes the gradient of a loss function in each iteration, thereby improving the model’s performance through gradual optimization27,28.

For this study, the GBDT model was configured with 350 trees, a learning rate of 0.01, a maximum depth of 10, a minimum sample split size of 5, and a minimum sample size per leaf of 2. The learning rate of 0.01 ensured stable updates, minimizing overfitting risks, while the maximum depth of 10 captured nonlinear relationships effectively without compromising generalization. The combination of a larger number of trees and a smaller learning rate balanced accuracy with computational efficiency.

While GBDT achieved high classification accuracy (94.73%) in this study, its sequential nature made it more sensitive to parameter tuning compared to RF. The reliance on incremental corrections also increased the model’s susceptibility to overfitting in datasets with high feature dimensions.

The core idea of GBDT is to adjust the model step-by-step by minimizing the gradient of the loss function, thereby improving classification accuracy. For a given input dataset, the output of the GBDT model can be expressed as:

Where \(\:{h}_{m}\left(x\right)\) represents the decision tree trained in the mmm-th iteration, and MMM is the total number of decision trees. In each iteration, the model is optimized by minimizing the gradient of the loss function L(y, F(x)) updating the model as follows:

Where\(\:\:\partial\:\) represents the learning rate, which controls the contribution of each tree to the final model.

ANN

The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) is a nonlinear classification model inspired by biological neural networks. It consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, where neurons are interconnected through weights and activation functions. ANN learns the nonlinear mapping between input data and output classes by iteratively adjusting weights during training29,30.

The Artificial Neural Network (ANN) is a nonlinear classification model inspired by biological neural networks. It consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, where neurons are interconnected through weights and activation functions. ANN learns the nonlinear mapping between input data and output classes by iteratively adjusting weights during training29,30.

In this study, the ANN model was implemented using TensorFlow, configured with three hidden layers, a learning rate of 0.008, a batch size of 110, 150 iterations, and the Adam optimizer. The Adam optimizer was selected for its ability to handle sparse gradients and noisy data, ensuring stable convergence. A batch size of 110 balanced computational efficiency and training stability, while 150 iterations were sufficient to achieve optimal classification accuracy.

Despite its flexibility, the ANN model demonstrated lower performance (82.72% accuracy) compared to RF and GBDT. This is likely due to its dependence on large training datasets and sensitivity to network architecture, which posed challenges in a land use classification context with limited data. The calculation formula for each neuron in the ANN is as follows:

Where x1,x2, … ,xn represent the input data, w1,w2,… ,wn are the weights, b is the bias term, and z is the weighted sum. The activation function f(z) typically uses nonlinear functions, such as ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) or Sigmoid. The calculation formula is as follows:

Where a represents the output of the neuron.

Methodology for land use driving factors

The Geographical Detector is a statistical tool used to detect spatial differentiation of geographical phenomena and the explanatory power of their driving factors. It is particularly suitable for analyzing the driving factors of land use change22. The core concept of the Geographical Detector is to evaluate the explanatory power of various factors on the target variable by comparing the spatial consistency of geographical attributes across different regions. Unlike traditional methods, the Geographical Detector does not require assumptions about linear relationships between variables, making it ideal for complex, nonlinear, or multi-factor interactions in spatial phenomena23. Therefore, it has been widely applied in land use research.

The fundamental principle of the Geographical Detector is based on the hypothesis that if the spatial distribution of a geographical phenomenon is similar to that of a driving factor, then the factor can explain the spatial differentiation of the phenomenon31,32,33. The key to this method is to calculate the explanatory power of factors on spatial differentiation, usually expressed by the “q-statistic,” which is calculated using the following formula:

The q-value ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher q-value indicating a stronger explanatory power of the driving factor on the target variable.

Land use simulation analysis

To predict future land use changes in Changsha City, this study used the current land use map from 2023 as a basis and employed the GeoSOS-FLUS model to simulate land use changes for the year 20306,34. The GeoSOS-FLUS model, developed by Liu et al., is an improved version of the traditional Cellular Automata (CA) model. The grid size was set to (7896, 6338), with a spatial resolution of 30 m35. The model utilizes extensive learning and iterations through the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) algorithm to simulate the complex relationships between input data and the set targets, calculating the suitability probabilities of various land use types within the study area6. The simulation incorporated driving factors such as topographic, socioeconomic, vegetation, and climatic factors specific to Changsha City. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula, \(\:sp\left(p,k,t\right)\) represents the suitability probability of land type k in grid p at time t, and the sum of the suitability probabilities for all land categories equals 1;\(\:{w}_{j,k}\) denotes the adaptive weights between the output layer and the hidden layer, which are adjusted based on the training results. The sigmoid function is the activation function between the hidden layer and the output layer. \(\:{net}_{j}\left(p,t\right)\) refers to the signal received by hidden layer j at grid p at time t.

Based on the Cellular Automata combined with the roulette wheel selection, the adaptive inertia competition mechanism is evaluated. The equation for the adaptive inertia coefficient of land type k at time t is as follows:

In the simulation of future land use changes in Changsha City, various constraints were considered to ensure the validity and controllability of the predictions regarding future urban development and trends in construction land expansion. This study was based on the “Changsha City Territorial Spatial Plan (2021–2035)” published in 2022, and combined with the planning requirements from relevant literature to simulate the expansion of construction land. According to these planning agreements, location factors for different land types were preset for the simulation experiments.

The parameter range for neighborhood factors was set from 0 to 1, where values closer to 1 indicate stronger expansion capabilities for that land type. Additionally, a conversion cost matrix was established to control the transformation rules between different land types (Table 2). During the process, the conversion of water bodies to construction land was strictly prohibited, and the default acceleration factor was set to 0.1 to control the speed of land type conversion36. A value of 0 indicates that land type conversion is not allowed in that area, while a value of 1 allows conversion. Based on this setup, three conversion cost matrices were developed: the natural development scenario, the farmland protection scenario, and the urban expansion control scenario. These matrices were used to construct three corresponding land use development models.

Each of the three scenarios was designed with specific constraints and assumptions: Natural Development Scenario: This scenario assumes no external policy interventions, with land use changes driven primarily by market demand, economic development, and population growth. Conversion costs are generally low, reflecting minimal restrictions on land type transformations, except for water bodies, which are strictly prohibited from being converted to construction land. Farmland Protection Scenario: Emphasizing the preservation of existing agricultural resources, this scenario imposes higher conversion costs for farmland to construction land, limiting urban encroachment into farmland. Other land types, such as forests and grasslands, have moderate conversion costs, balancing development needs with farmland conservation objectives. Ecological control scenario: This scenario prioritizes environmental preservation and restoration, particularly for forests, grasslands, and water bodies. Conversion costs for ecologically sensitive land types are set to prohibitively high levels, effectively curbing urban expansion into these areas.

Uncertainty analysis reveals that the accuracy of scenario predictions depends on factors such as economic growth, population trends, and policy implementation. While the model incorporates robust constraints and parameters, unexpected socio-economic or environmental events could influence the actual outcomes. Future studies should consider integrating dynamic parameters to address these uncertainties more effectively.

Results

Comparison of accuracy among three land use classification methods in Changsha City

The accuracy of land use classification in Changsha City was evaluated using three methods: Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Random Forest (RF), and Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT). The overall accuracies (OA) achieved by these methods were 82.72%, 95.78%, and 94.73%, respectively (Table 3). The results clearly demonstrate that the RF method is the most suitable for land use classification in Changsha.

The superior performance of the RF model can be attributed to its ensemble-based structure, where multiple decision trees are built using randomly sampled data with replacement, and each tree is constructed using a random subset of features. This inherent diversity reduces the sensitivity to noise and outliers, making the RF model more robust and capable of handling high-dimensional and complex land use datasets.

In contrast, while GBDT also relies on decision trees, it adopts a sequential training approach where each tree is built to correct the errors of the previous one. This sequential nature, though effective for improving accuracy, increases the risk of overfitting, particularly when applied to datasets with numerous features or significant noise.

ANN, on the other hand, depends heavily on large training datasets and is more sensitive to variations in network structure and parameter selection. These dependencies make ANN more prone to fluctuations in classification accuracy, which could explain its relatively lower performance in this study.

Given its superior robustness, accuracy, and generalization ability, the RF method was selected for subsequent analyses in this study.

The spatiotemporal patterns of construction land changes in Changsha City

From 2000 to 2023, the construction land in Changsha City expanded significantly, increasing from 563.82 km2 to 1628.20 km2, nearly tripling in size. This remarkable growth was consistently captured by all three classification models: Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT), and Artificial Neural Network (ANN), which demonstrated a clear upward trend in construction land area (Table 4; Fig. 2).

The most rapid expansion occurred between 2010 and 2015, with the GBDT model showing a particularly notable increase from 819.63 km2 in 2010 to 1322.65 km2 in 2015. This period of rapid urbanization coincided with the implementation of China’s national “New Urbanization” strategy, which facilitated large-scale migration from rural to urban areas. The resulting surge in demand for housing, infrastructure, and public services contributed significantly to the expansion of construction land.

After 2020, although the growth rate of construction land slowed, it maintained a steady upward trajectory, exceeding 1600 km2 across all models by 2023. The RF model estimated the construction land area to be 1628.20 km2, while the GBDT and ANN models yielded slightly higher and lower estimates, at 1785.56 km2 and 1620.85 km2, respectively.

Overall, from 2000 to 2023, Changsha City experienced substantial construction land expansion, particularly post-2010, driven by factors such as rapid urbanization, economic development, supportive policy measures, and population growth. This growth trend underscores the profound impact of socio-economic and policy-driven changes on urban land use dynamics.

Analysis of driving factors of land use in Changsha City

Single factor detection

This section examines the primary factors influencing land-use changes in construction land in Changsha City, as depicted in Fig. 3. Using construction land changes as the dependent variable and 12 driving factors as independent variables, their respective impacts were analyzed. The results are presented in bar charts, with each color representing a specific year (2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020, 2023). The q-values derived from the univariate detection indicate the relative influence of each factor on land-use changes.

The order of influence for the univariate detection is as follows: X8 > X10 > X9 > X3 > X11 > X4 > X12 > X5 > X7 > X1 > X6 > X2. This ranking underscores the predominant role of anthropogenic factors such as X8 and X10, which consistently exhibited the highest q-values across all years. The strong influence of the Nighttime Light Index reflects the impact of urbanization and human activity, while population density highlights the significance of settlement patterns and demographic changes in driving land-use transformations.

Natural factors such as Slope (X1) and Aerosol (X6) showed relatively low q-values, suggesting their limited direct impact on construction land changes. However, their influence may interact with other factors over time, especially in areas with challenging topography or significant environmental constraints.

Some factors, such as annual average temperature (X3) and Leaf Area Index (X4), exhibited notable fluctuations in their q-values across different periods. These variations indicate that their influence on land-use changes may be contingent on other conditions, such as climate policies or ecological restoration efforts, during specific years.

The analysis demonstrates that urbanization-related anthropogenic factors, particularly nighttime light index and population density, play a dominant role in driving land-use changes in Changsha City. In contrast, natural factors generally have a weaker influence, although their role may vary over time due to specific environmental or policy-related contexts. These findings highlight the importance of focusing on human activity and urbanization patterns when developing strategies for sustainable land management.

Single factor detection influencing factors. X1: Slope, X2: Soil Salinity, X3: Annual Average Temperature, X4: Leaf Area Index, X5: Soil Moisture, X6: Aerosol, X7: Aspect, X8: Nighttime Light Index, X9: DEM (Digital Elevation Model), X10: Population Density, X11: Vegetation Coverage, and X12: Annual Precipitation.

Interaction detection

These figures illustrate the interaction effects among 12 influencing factors on land-use changes in construction land in Changsha City (Fig. 4). The variations across different periods (2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2020, and 2023) are represented by color intensity, where darker red indicates a stronger positive correlation, and blue represents a weaker or negative correlation.

In 2000, the strongest interactions were observed between X8 (Nighttime Light Index) and factors such as X9 (DEM) and X10 (Population Density), highlighting the dominant role of anthropogenic factors. In contrast, weaker interactions were noted between X1 (Slope) and X9 (DEM), suggesting that natural topographical factors had a limited impact on land-use changes during this year37.

By 2005, X8 (Nighttime Light Index) maintained strong interactions with X10 (Population Density), further emphasizing the influence of urbanization. Additionally, a notable increase in the interaction between X7 (Aspect) and X6 (Aerosol) was observed, possibly reflecting the combined effects of climatic and geographical factors. However, natural factor interactions, such as between X1 (Slope) and X3 (Annual Average Temperature), remained weak, reaffirming the predominance of anthropogenic influences.

In 2015, the strong interaction between X8 (Nighttime Light Index) and X10 (Population Density) persisted, reflecting intensified urbanization. Meanwhile, X12 (Annual Precipitation) showed a significant interaction with X4 (Leaf Area Index), possibly linked to ecological restoration or vegetation management initiatives. By 2020, interactions between X6 (Aerosol) and X4 (Leaf Area Index) became more prominent, potentially reflecting the impact of air pollution and climate change on vegetation. The interaction between X10 (Population Density) and X8 (Nighttime Light Index) remained strong, continuing the long-term trend.

Finally, in 2023, the interaction between X12 (Annual Precipitation) and X4 (Leaf Area Index) further intensified, underscoring the growing role of climatic factors in vegetation and ecological restoration. However, the interaction between X10 (Population Density) and X8 (Nighttime Light Index), while still dominant, showed a slight decline, possibly indicating a stabilization in urbanization.

Overall, the figures reveal that anthropogenic factors, particularly the interaction between X8 (Nighttime Light Index) and X10 (Population Density), have consistently driven land-use changes in construction land over time. However, natural factors, including X12 (Annual Precipitation), X4 (Leaf Area Index), and other climate-related variables (e.g., X3: Annual Average Temperature and X6: Aerosol), have gradually gained importance, reflecting an increasing influence of ecological restoration and climate change on land-use dynamics. These findings suggest a long-term transition from predominantly anthropogenic to a more balanced interplay between human and natural factors38,39.

Simulation and prediction of spatiotemporal changes of construction land

The data presented in Table 5; Fig. 5 illustrates the projected trends in construction land area under three different land-use scenarios for 2023 and 2030. These scenarios—natural development, farmland protection, and ecological control—offer distinct perspectives on the potential growth of construction land in Changsha City.

Under the natural development scenario, the construction land area is projected to increase by 292.45 square kilometers, representing significant expansion. This scenario assumes no human intervention, allowing urban land to grow unchecked due to drivers such as population growth, economic development, and rising demand for urban infrastructure. However, this unregulated expansion risks encroaching on surrounding agricultural and ecological land, potentially exacerbating conflicts over land use and environmental degradation.

In the farmland protection scenario, the projected increase in construction land is more moderate, at 198.12 square kilometers. This scenario reflects policies aimed at preserving agricultural land by restricting urban expansion into farmland. Although urban development continues to meet growing demands, the stricter regulatory controls help to mitigate the sharp increases seen in the natural development scenario. This balance demonstrates the effectiveness of targeted land-use policies in controlling urban sprawl while accommodating necessary growth.

The ecological control scenario predicts the smallest increase in construction land, with only 74.46 square kilometers of growth. This minimal expansion is attributed to stringent ecological policies prioritizing environmental protection and restoration. Measures such as ecological redline enforcement and habitat preservation restrict urban encroachment into ecologically sensitive areas, emphasizing sustainable development40. By curbing urban sprawl, this scenario highlights the importance of ecological considerations in future land-use planning.

Discussion

The simulation results of construction land expansion in Changsha City from 2000 to 2023, based on the GeoSOS-FLUS model, reveal significant urban growth and provide insights into future land use trends under different scenarios. This study not only illustrates the characteristics of construction land expansion under rapid urbanization but also highlights the role of various influencing factors in land use changes, offering valuable references for urban planning and land management.

Firstly, in terms of land use classification accuracy, the Random Forest (RF) model demonstrated the highest accuracy (95.78%), outperforming the Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models. This aligns with previous studies where the RF model exhibited robustness and generalization capability in land use classification tasks41. In contrast, although GBDT showed certain advantages, its sequential training nature made it prone to overfitting in datasets with high feature dimensions, which explains its slightly lower classification accuracy compared to RF. The ANN model, constrained by the training data and network structure, exhibited greater variability in accuracy, consistent with findings from other studies42. Consequently, the RF model was selected for subsequent analyses due to its higher accuracy and stability. Secondly, the expansion of construction land in Changsha is comparable to findings from existing literature on urbanization processes. For instance, examined the expansion of construction land in the Yangtze River Middle Reaches urban agglomeration, concluding that construction land expansion significantly accelerated after 201043. This trend is highly consistent with the significant expansion of construction land in Changsha from 2010 to 2015 observed in this study. Li44also noted that the implementation of China’s “New Urbanization” strategy was a key driver of rapid construction land expansion, a conclusion further validated by our analysis. While the “New Urbanization” strategy undoubtedly played a pivotal role by encouraging rural-to-urban migration and supporting urban infrastructure development, this expansion was also driven by other interconnected factors. Firstly, socio-economic development during this period significantly contributed to the construction land boom. Changsha experienced robust economic growth, with its GDP increasing steadily, driven by rising industrial output and expanding tertiary industries. This economic momentum increased the demand for urban land to accommodate new commercial centers, industrial parks, and housing developments45. Secondly, the adjustment of the industrial structure further influenced land use patterns46. As Changsha shifted from a primarily manufacturing-based economy to one emphasizing services and high-tech industries, the demand for specialized urban zones, such as technology parks and logistics hubs, surged, prompting the conversion of rural and unused land into construction land. Additionally, changes in land policies provided crucial support for this expansion. During this period, the central and local governments implemented more flexible land use policies, including expedited land approval processes and incentives for urban development projects. Policies encouraging public-private partnerships and infrastructure investment also created favorable conditions for large-scale urban expansion. Furthermore, infrastructure projects such as the Changsha Metro and urban road networks were developed, enhancing the connectivity and attractiveness of peripheral areas, thus fueling the outward expansion of construction land. In summary, the rapid expansion of construction land in Changsha between 2010 and 2015 was a multifaceted phenomenon. While the “New Urbanization” strategy served as a key driver, socio-economic growth, industrial restructuring, and supportive land policies collectively reinforced this trend. These interconnected factors underline the complexity of urban land use changes during this critical period.

Moreover, an in-depth analysis of the factors influencing construction land changes in Changsha, using the Geographical Detector tool, revealed that nighttime light index (X8) and population density (X10) had the most significant impacts among anthropogenic factors. This is consistent with Li, who also found a strong correlation between the nighttime light index, serving as a proxy for urbanization, and land use changes in eastern China’s urban agglomerations47. In contrast, natural factors, such as slope and aerosols, had relatively minor effects, which differs from findings in other regions. For example, Zhang found that natural topographic factors played a more prominent role in land use changes in the mountainous regions of southwest China, likely due to differences in terrain and the implementation of ecological protection policies48. Interaction analysis in this study also revealed that the combined effects of anthropogenic factors, such as the interaction between the nighttime light index and population density, have long dominated the trends in construction land changes in Changsha. This conclusion is in line with Wang, who pointed out that strong interactions between anthropogenic factors are often key drivers of land use changes in rapidly urbanizing regions of China49. However, this study also found that, over time, the interaction between natural factors, such as annual precipitation and leaf area index, gradually intensified, especially after 2020. This trend may suggest that as urbanization progresses, ecological restoration and climate change are becoming increasingly influential in construction land expansion. This finding echoes conclusions from Liu, who highlighted the growing importance of climate factors in long-term land use changes in northern cities undergoing ecological restoration50.

Lastly, simulation results under different scenarios indicate that under the natural development scenario, construction land in Changsha will continue to grow significantly, a result that aligns with the projected trends in many rapidly urbanizing regions globally51. In contrast, under scenarios involving farmland protection and ecological control, the growth of construction land is moderated, with the ecological control scenario significantly curbing land expansion. This finding is consistent with the effects observed in cities that have adopted eco-prioritized development strategies, such as those aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals52. However, the feasibility and implementation of the ecological control scenario warrant further validation. Successful implementation of such a scenario hinges on several key conditions. Firstly, strict land use policies must be enacted and enforced, such as the designation of ecological red lines and the prohibition of construction in environmentally sensitive areas. Changsha’s existing land use plans would need to integrate these policies effectively, with clear guidelines and accountability mechanisms. Secondly, substantial investment in ecological restoration and green infrastructure is essential to offset the pressure of urban expansion53,54. For instance, projects aimed at increasing urban green spaces, improving water resource management, and enhancing biodiversity within urban boundaries would play a crucial role in ensuring the ecological control scenario’s success. The availability of financial resources and public support for these initiatives is a critical factor in their feasibility. Thirdly, achieving minimal construction land growth under the ecological control scenario requires fostering economic and social resilience through alternative urban development strategies. Promoting higher urban density and mixed-use development can optimize land use efficiency while minimizing the need for expansion55. Additionally, smart city technologies, such as land use monitoring systems and urban planning models, can help manage growth more effectively and prevent uncontrolled sprawl. Lastly, the implementation of the ecological control scenario depends on addressing potential conflicts between development goals and environmental preservation. Collaborative governance involving multiple stakeholders, including local authorities, private developers, and community groups, is essential to align interests and build consensus for sustainable urban growth. In conclusion, while the ecological control scenario demonstrates significant potential in curbing construction land expansion, its practical application requires addressing institutional, financial, and social challenges. By ensuring that these enabling conditions are met, the ecological control scenario could serve as a robust model for balancing urban development with environmental sustainability in Changsha and other rapidly urbanizing cities.

In summary, this study provides a scientific basis for future land use changes in Changsha City, while exploring how to strike a balance between development and ecological protection through scenario-based simulations. These findings offer important references for future urban planning in Changsha and provide valuable insights for land use management in other rapidly urbanizing regions.

Conclusion

This study systematically analyzes land use changes in Changsha City from 2000 to 2023, combining multiple models (ANN, RF, GBDT) with driving factor detection to provide a comprehensive understanding of the key drivers of construction land expansion and their spatiotemporal dynamics. The findings highlight that the Random Forest (RF) model exhibited the highest accuracy, outperforming other models in robustness and generalization, particularly when addressing the complex land-use patterns in Changsha City.

Over the study period, construction land in Changsha nearly tripled, with the most rapid expansion occurring after 2010, coinciding with China’s “New Urbanization” strategy. This reflects the significant influence of anthropogenic factors, such as the Nighttime Light Index (X8) and Population Density (X10), which consistently emerged as the dominant drivers of land-use changes. Strong interactions between these factors underscore the profound impact of urbanization-related activities on construction land expansion, far surpassing the influence of natural factors.

However, the study also reveals that the role of natural factors, including Annual Precipitation (X12) and Leaf Area Index (X4), has gradually increased over time. This trend is particularly evident in the later years, driven by ecological restoration efforts and the effects of climate change. These findings suggest an evolving interplay between anthropogenic and natural influences on land-use dynamics.

Simulation results under different land-use scenarios further demonstrate the critical role of policy interventions in shaping urban expansion. The natural development scenario, characterized by an absence of policy regulation, resulted in the most significant construction land growth, reflecting the unregulated progression of urbanization. In contrast, the farmland protection and ecological control scenarios effectively curtailed land expansion, with the ecological control scenario achieving the most pronounced restriction. This underscores the importance of ecological policies in mitigating urbanization pressures on natural resources and promoting sustainable development.

In conclusion, land-use changes in Changsha City have been primarily driven by anthropogenic factors, with an increasing contribution from natural factors in recent years. The findings emphasize that policy regulation and intervention are pivotal in guiding future urban expansion. To achieve sustainable urban development, future land-use planning should prioritize the implementation of ecological and farmland protection policies. Rational urbanization strategies that balance economic, social, and environmental objectives will be essential for fostering a harmonious and sustainable urban future.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wei, Y. D. & Ye, X. Urbanization, urban land expansion and environmental change in China. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 28, 757–765 (2014).

Zhong, Q. K. et al. Revealing multiscale and nonlinear effects of urban green spaces on heat islands in high-density cities: Insights from MSPA and machine learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 120, 106173 (2025).

Liu, J., Zhan, J. & Deng, X. Spatio-temporal patterns and driving forces of urban land expansion in China during the economic reform era. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 34 (6), 450–455 (2005).

Tian, L., Ge, B. & Li, Y. Impacts of state-led and bottom-up urbanization on land use change in the peri-urban areas of Shanghai: planned growth or uncontrolled sprawl? Cities 60, 476–486 (2017).

Agatonovic-Kustrin, S. & Beresford, R. Basic concepts of artificial neural network (ANN) modeling and its application in pharmaceutical research. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 22 (5), 717–727 (2000).

Wang, J. et al. Land-use pattern evaluation using GeoSOS-FLUS in National territory Spatial planning: a case study of Changzhi City, Shanxi Province. Sustainability 14 (21), 13752 (2022).

Chen, X., He, X. & Wang, S. Simulated validation and prediction of land use under multiple scenarios in Daxing district, Beijing, China, based on GeoSOS-FLUS model. Sustainability 14 (18), 11428 (2022).

Kai, J. et al. Spatial distribution simulation and trend analysis of land use in Sanya based on GeoSOS-FLUS model. Urban Reg. Plann. 9 (2), 97–108 (2020).

Cao, S. et al. Coupled MOP and GeoSOS-FLUS models research on optimization of land use structure and layout in Jintan district. J. Nat. Resour. 34 (6), 1171–1185 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Does rural residential land expansion pattern lead to different impacts on eco-environment? A case study of loess hilly and gully region, China. Habitat Int. 117, 102436 (2021).

Chai, B. & Li, P. Annual urban expansion extraction and spatio-temporal analysis using Landsat time series data: a case study of Tianjin, China. EEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 11 (8), 2644–2656 (2018).

Herold, M., Goldstein, N. C. & Clarke, K. C. The Spatiotemporal form of urban growth: measurement, analysis and modeling. Remote Sens. Environ. 86 (3), 286–302 (2003).

Liu, X. et al. High-spatiotemporal-resolution mapping of global urban change from 1985 to 2015. Nat. Sustain. 3 (7), 564–570 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. Risk management for optimal land use planning integrating ecosystem services values: A case study in Changsha, middle China. Sci. Total Environ. 579, 1675–1682 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Delineation of a basic farmland protection zone based on Spatial connectivity and comprehensive quality evaluation: a case study of Changsha City, China. Land. Use Policy. 101, 105145 (2021).

Zhang, B. et al. The Changsha historic urban area: a study on the evolution characteristics and influencing factors of the connectivity of construction land. Herit. Sci. 12 (1), 287 (2024).

Xiong, Y. & Zhang, F. Effect of human settlements on urban thermal environment and factor analysis based on multi-source data: A case study of Changsha City. J. Geog. Sci. 31 (6), 819–838 (2021).

Yang, W., Wong, N. H. & Zhang, G. A comparative analysis of human thermal conditions in outdoor urban spaces in the summer season in Singapore and Changsha, China. Int. J. Biometeorol. 57, 895–907 (2013).

Irons, J. R., Dwyer, J. L. & Barsi, J. A. The next Landsat satellite: the Landsat data continuity mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 122, 11–21 (2012).

Hansen, M. C. & Loveland, T. R. A review of large area monitoring of land cover change using Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 122, 66–74 (2012).

Zhu, Z. et al. Benefits of the free and open Landsat data policy. Remote Sens. Environ. 224, 382–385 (2019).

Ricart, S. & Rico, A. M. Assessing technical and social driving factors of water reuse in agriculture: A review on risks, regulation and the yuck factor. Agric. Water Manag. 217, 426–439 (2019).

Zhou, Y., Li, X. & Liu, Y. Land use change and driving factors in rural China during the period 1995–2015. Land. Use Policy. 99, 105048 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Coupling coordination degree Spatial analysis and driving factor between socio-economic and eco-environment in Northern China. Ecol. Ind. 135, 108555 (2022).

Alshari, E. A., Abdulkareem, M. B. & Gawali, B. W. Classification of land use/land cover using artificial intelligence (ANN-RF). Front. Artif. Intell. 5, 964279 (2023).

Li, L. et al. WindSat radio-frequency interference signature and its identification over land and ocean. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44 (3), 530–539 (2006).

Jun, M. J. A comparison of a gradient boosting decision tree, random forests, and artificial neural networks to model urban land use changes: the case of the Seoul metropolitan area. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 35 (11), 2149–2167 (2021).

Ma, J. et al. Analyzing driving factors of land values in urban scale based on big data and non-linear machine learning techniques. Land. Use Policy. 94, 104537 (2020).

Rahman, M. T. U. et al. Temporal dynamics of land use/land cover change and its prediction using CA-ANN model for Southwestern coastal Bangladesh. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189, 1–18 (2017).

Gharaibeh, A. et al. Improving land-use change modeling by integrating ANN with cellular Automata-Markov chain model. Heliyon, 6(9). (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Digital economy: an innovation driving factor for low-carbon development. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 96, 106821 (2022).

Ganteaume, A. et al. A review of the main driving factors of forest fire ignition over Europe. Environ. Manag. 51, 651–662 (2013).

Walsh, S. P. et al. Dialling and driving: factors influencing intentions to use a mobile phone while driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 40 (6), 1893–1900 (2008).

Shu-qiang, C. U. I. et al. Longitudinal Transmission of Core Indicators of Municipal Territory Spatial Planning: A Case Study of Changde City, Hunan Province. J. Nat. Resour. 11, 372819–2836. (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Spatio-temporal variation and future multi-scenario simulation of carbon storage in Bailong river basin using GeoSOS-FLUS and invest models. (2023).

Wu, C., Jiang, A. & Zheng, W. Study on the measures for optimizing China’s provincial territorial space based on the perspective of resource and environmental carrying capacity in the new situation. Sustainability 14 (21), 13754 (2022).

Dong, Y. & Tang, G. Comparison of popular methods for simplifying terrain based on grid DEMs. 2010 The 2nd Conference on Environmental Science and Information Application Technology. IEEE. 3, 227–230. (2010).

Ding, Q. et al. Effects of natural factors on the Spatial distribution of heavy metals in soils surrounding mining regions. Sci. Total Environ. 578, 577–585 (2017).

Peng, W., Kuang, T. & Tao, S. Quantifying influences of natural factors on vegetation NDVI changes based on geographical detector in Sichuan, Western China. J. Clean. Prod. 233, 353–367 (2019).

Xiong, Y. et al. Analog simulation of urban construction land supply and demand in Chang-Zhu-Tan urban agglomeration based on land intensive use. J. Geog. Sci. 29, 1346–1362 (2019).

Liu, Y., Wang, H. & Zhang, X. Land use classification based on random forest in urban areas: A comparative study. Remote Sens. 13(2), 345–357.

Zhao, Q., Li, J. & Chen, Z. Evaluating machine learning algorithms for land use classification: A comparison between random forest and gradient boosting. J. Environ. Manag.. 258, 110–123.

Zhong, Q. k. et al. Spatial-temporal dynamics and vulnerability analysis of population, economy, and environment in mountainous urban agglomerations: a perspective on coordinated development. Geomatics, Nat. Hazards Risk. 16(1), 2437061 (2025).

Li, X., Chen, F. & Wu, J. Urban expansion in the middle Yangtze river urban agglomeration: trends and driving forces. Chin. Geogra. Sci. 32(4), 567–579 .

Liu, B. et al. Spatial distribution, influencing factors and innovative development countermeasures of farmer cooperatives in Hunan Province, China. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 11308 (2024).

Zhang, J., Xu, R. & Chen, J. Does industrial land marketization reform faciliate urban land use efficiency? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 96, 103609 (2024).

Li, J., Zhou, Y. & Gu, J. Nighttime light data as a proxy for urbanization: Implications for land use and environmental studies. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125(7), eJD032356. (2020).

Zhang, Z., Liu, H. & Li, Y. The role of topography in land use changes in Southwest China: A case study in the mountainous areas. J. Mt. Sci., 18(3), 355–368.

Wang, S., Wu, Q. & Zhang, M. The role of human factors in land use changes in rapidly urbanizing regions. Land. Use Policy, 101, 105–114.

Liu, Q., Zhou, X. & Yu, T. Climate change and land use dynamics: case studies in Northern China. Environ. Res. Lett. 18(2), 250–264.

Zhou, L., Liu, P. & Huang, J. Predicting urban land expansion under different scenarios: A global comparison. Urban Stud., 59(4), 772–790.

United Nations (UN). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. United Nations. (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Uncovering the role of urban green infrastructure in carbon neutrality: A novel pathway from the urban green infrastructure and cooling power saving. J. Clean. Prod. 452, 142193 (2024).

Ben, M. et al. Spatial-Temporal dynamics of urban green spaces in response to rapid urbanization and urban expansion in Tunis between 2000 and 2020. Land 13 (1), 98 (2024).

Koroso, N. & Zevenbergen, J. Urban land management under rapid urbanization: exploring the link between urban land policies and urban land use efficiency in Ethiopia. Cities 153, 105269 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Professors for their very helpful and constructive input. This article would like to acknowledge funding supports from Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No.2025JJ50235); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.52078484).

Funding

This article was funded supports from Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No.2025JJ50235); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.52078484).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: Z.Z. and Z.L.; methodology: Z.Z. and Z.L.; formal analysis: Z.Z. and Z.L.; resources: Z.Z. and Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation: Z.Z., Z.L., and Z.L.; writing—review and editing: Z.Z., Z.L., and Z.L.; visualisation: Z.Z. and Z.L.; supervision: Z.L. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Li, Z. & Li, Z. Evaluating the change and trend of construction land in Changsha City based GeoSOS-FLUS model and machine learning methods. Sci Rep 15, 9602 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93689-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93689-9