Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effects of dietary supplementation with Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) on lactation performance, rumen microbial communities, and metabolism in dairy goats under heat stress conditions. Twenty Guanzhong dairy goats with the same parity, similar lactation period (120 ± 15 days), and similar milk yield (1.20 ± 0.16 kg/day) were randomly divided into two groups, with 10 replicates in each group. The control group was fed a standard diet, while the experimental group was supplemented with 0.5 mg SeNPs/kg DM based on the standard diet. The pretrial period lasted for seven days, followed by a 30-day trial period. The results showed that dietary supplementation with SeNPs significantly increased milk yield, milk fat and lactose content in dairy goats, under heat stress conditions. SeNPs significantly altered the composition of the rumen microbiota, increasing the relative abundance of Prevotella and Ruminococcus while decreasing the relative abundance of Succiniclasticum. This enhanced the rumen’s ability to degrade starch and fiber under heat stress conditions. Non-targeted metabolomic analysis revealed a total of 119 differential metabolites between the two groups, indicating changes in rumen metabolism. Further correlation analysis indicated that Rumen bacterium R-21 was positively correlated with propionate, while Ralstonia insidiosa was negatively correlated with γ-glutamylcysteine. Additionally, several differential microbes, including Succinivibrio dextrinosolvens, Rummeliibacillus pycnus, Ralstonia insidiosa, and Prevotella sp BP1-56, were significantly correlated with milk composition. In conclusion, dietary supplementation with SeNPs can positively impact milk yield, milk components, and metabolism in dairy goats by improving the composition of the rumen microbiota under heat stress conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing occurrence of greenhouse effects and extreme weather patterns driven by global warming, animals frequently exhibit a series of heat stress symptoms, including rapid breathing, elevated heart rate, weight loss, decreased immune function, etc. These seriously harm animal’s health and their production performance. Under heat stress, the normal thermal equilibrium of an animal’s organism is disrupted, leading to a decrease of feed intake and an increase of oxidative metabolism1,2,3,4. The decrease in feed intake is a major factor contributing to the decline in milk yield5. Meanwhile, heat stress can also disrupt the gastrointestinal function of animals and increase intestinal permeability, which results in harmful substances more easily infiltrating the body through the gastrointestinal tract6. Disruption of gut barrier integrity leads to increase in blood endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides, LPS), which induces hypoglycemia, ultimately resulting in a decrease in milk yield7,8. Heat stress is detrimental to gut homeostasis and can significantly decrease the abundances of Prevotella and Ruminococcaceae9. During heat stress, changes in rumen microbiota significantly reduce the ability of starch and fiber degradation and downregulate the metabolism of carbohydrate, lipid and cofactors and vitamins10,11.

Selenium is an essential trace element for animal growth12,13. Selenium deficiency has led to Mulberry heart disease in piglets, reducing their nutrient absorption rate14. Selenium deficiency has caused white muscle disease (WMD) in calves, with clinical manifestations including stiffness and weakness, which severely impact the growth performance15. Appropriate selenium supplementation not only effectively promotes growth performance, but also prevents the occurrence of these fatal diseases16. A study has found that Na2SeO4 increased the relative abundance of rumen bacteria, fungi, fiber-degrading bacteria, and starch-degrading bacteria in lactating cows17. Supplementing yeast selenium in sheep diets has increased the abundance of bacteria correlated with rumen carbohydrate metabolism and protein metabolism18. Selenium also alleviates the oxidative stress state and reduces inflammation caused by heat stress in animals. Furthermore, selenium promotes feed efficiency by regulating the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins19. And dietary supplementation with selenium can effectively alleviate inflammation in mammary tissue, boost thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) levels, enhance antioxidant capacity, and ultimately improve milk yield20.

Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) are a new type of selenium sources with a large specific surface area and high reactivity. Compared with conventional selenium sources, such as elemental selenium, SeO2 and Na2SeO3, SeNPs exhibit greater safety, lower toxicity, and stronger biological activity21. SeNPs has been shown to increase the feed intake of broilers under heat stocking density (HSD)22. Dietary supplementary SeNPs (0.1 mg/kg DM for 60 days) significantly increased the weight gain of young lambs23. During heat stress, dietary supplementation of SeNPs increased the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) , the antioxidant status of colon epithelium and food intake in goats24. Dietary supplementation of SeNPs significantly reduced oxidative stress caused by heat stress in dairy cows and significantly increased the expression of glutathione peroxidases (GSH-PX1, GSH-PX2, and GSH-PX4) in the mammary gland25.

Most previous research focused on the effects of SeNPs on animal production performance, such as growth rate, feed conversion efficiency, and antioxidant capacity. However, under heat stress conditions, the effects of dietary supplementation with SeNPs on lactation, rumen microbial community and metabolism of ruminants remain to be investigated.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

The research protocol for this project has been reviewed by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences (file no: CQWLDF0030). We also obtained consent from the animal owners for their participation in the study. All the experiment was performed in accordance with the university’s guidelines and regulations for animal research (following the ARRIVE guidelines26).

Experimental material and animal

SeNPs was gifted from Bosar Biology Co.,Ltd., with a purity of 98%. The partical size of the SeNPs was 20–90 nm. The Guanzhong dairy goats were from the Black Goat Breeding Base (Chongqing, China). Temperature and humidity variations are monitored daily using temperature and humidity meters (Weimengshi, Jinan, China) in sheepfolds.

Experimental design

Twenty Guanzhong dairy goats with the same parity, similar lactation period (120 ± 15 days), and similar milk yield (1.20 ± 0.16 kg) were randomly allocated to two groups (control group vs. SeNPs group), with 10 replicates in each group. The control group of dairy goats was fed a regular diet (Table 1), while the SeNPs group received the same regular diet supplemented with selenium nanoparticles at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg DM. The pre-trail period was 7 days, followed by a 30 days trial period. The dairy goats had free access to feed and water and were managed according to the standard procedures of the sheep farm.

Sample collection

Feed intake was measured as the difference between the amount of feed offered and the remaining feed. Milking was performed using an automatic vacuum milking machine, and the daily milk yield of each dairy goat was recorded. Manual milking was performed every three days at 08:00 AM and 8:00 PM. The collected milk samples were placed into labeled 50 ml centrifuge tubes and stored at a temperature of 4 °C. The morning and evening milk samples were mixed in a 3:2 ratio to determine milk components.

On the last day of the trail, rumen fluid was collected from all the dairy goats using an oral stomach tube. The collected rumen fluid was transferred into cryopreservation tubes after filtering through four layers of sterile gauze and stored at − 80 °C for preservation. During the experimental period, temperature and humidity inside the sheepfolds were measured at 6 AM, 2 PM, and 10 PM. every day. This was used to calculate the daily average of temperature and humidity. The Temperature humidity Index (THI) calculation formula is as follows:

T is dry bulb temperature (°C) and RH is relative humidity in decimal form. THI in the range of 72–79 is considered as mild heat stress, 79–88 is considered as moderate heat stress, and 89 or more is considered as severe heat stress27.

As shown in Fig. 1, the average Temperature humidity Index in the goat house during the trial period was 79.19. Throughout the trial period, the dairy goats were in a state of heat stress.

Milk sample analysis

The mixed milk samples were heated to 37 °C using a water bath. The contents of fat, protein, lactose, non-fat milk solids, and solids in goat milk were measured using a milk analyzer (LACTOSCAN MCCW, The Republic of Bulgaria, EU).

16S rDNA sequencing

Microbial DNA was isolated from rumen samples using HiPure Soil DNA Kits (Magen,Guangzhou, China). The concentration and purity of the DNA samples were determined using a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000c (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), Agarose gel electrophoresis (Beijing Liuyi Instrument Plant, Beijing, China), and a Gel Doc XR System (TANON-2500, Shanghai, China). The V3–V4 region of 16S rDNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the universal 16S rDNA primers. The primer sequences used were 341F: 5'- CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3' and 806R: 5'-GGACTACHVGGGTATCTAAT-3'. After quantification of the PCR products, a small fragment library was constructed based on the characteristics of the amplified region. The high-throughput sequencing was performed on an Illumina Miseq PE250 platform (Illumina, San Diego, US). The 16S rDNA gene amplification and sequence analysis were performed by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Company (Guangzhou, China).

The sequencing data was processed using FASTP software (version 0.18.0) and USEARCH software (version 9.2.64) for filtering, merging, and removal of chimeras to obtain high-quality data. Subsequently, the USEARCH software (version 9.2.64) UPARSE algorithm was applied to cluster the data into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU) with a sequence similarity threshold of 97%. Species annotation was conducted using the Naive Bayesian assignment algorithm of the RDP Classifier software (version 2.2), with a confidence threshold set between 0.8 and 1. Based on the annotation results, LEfSe software (version 1.0) was used for microbial community difference analysis. QIIME (version 1.9.1) software was employed to analyze intra-sample diversity indices, and group differences were evaluated using the T-test. Additionally, PICRUSt2 (version 2.1.4) software was used to predict microbial functions, while T-tests were used to analyze and identify metabolites with significant differences.

Metabolomics analysis

After slowly thawing the samples at 4 °C, an appropriate amount of each sample was mixed with 100 μL of acetonitrile–water solution (acetonitrile: water = 1:1, v/v). After vortexing and centrifuging, the supernatant was analyzed. A quality control (QC) sample was inserted into the sample queue, and the samples were then separated using an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) system with a HILIC (Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography) column. Subsequently, the AB Triple TOF 6600 mass spectrometer was used to collect the primary and secondary spectra of the samples. The raw data were converted into MzXML files using ProteoWizard MSConvert, and then XCMS was employed to compare the converted data and to normalize the total peak area of the data. The metabolomics analysis was performed by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Company (Guangzhou, China).

After obtained the raw data, imported it into XCMS software (online 3.7.1). Extracted the raw data based on centWave m/z = 10 ppm, peak width = c (10,60), and pre filter = c (10,100). The CAMERA (Collection of Algorithms of MEtabolite pRofile Annotation) was utilized for the purpose of annotating isotopes and adducts. And then, compound identification of metabolites was performed by comparing of accuracy m/z value (< 10 ppm), and MS/MS spectra with an in-house database established with available authentic standards. The K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) was utilized to impute the missing data, while attributes exhibiting a Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) exceeding 50% were subsequently excluded from the analysis. Finally, the KEGG database used to map the annotated differential metabolites to the KEGG pathway database28,29,30.

Correlation analysis

The correlation between rumen microbial communities and milk yield and milk components were analyzed using the Pearson correlation analysis. The Pearson correlation coefficient between each level of microbiota and the metabolomic datasets were computed using the psych package within the R project (version 1.8.4). Subsequently, a correlation heatmap was generated employing the heatmap package in R (version 1.0.12).

Statistical analysis

The differences in production performance, dry matter intake, and milk composition between groups were analyzed using SPSS software (version 27.0) with the T-test. PICRUSt2 (version 2.1.4) software was used to predict microbial functions, and a T-test was used to analyze and screen for significantly differential metabolites. QIIME (version 1.9.1) software was used to analyze the intra-sample diversity indices. Tax4Fun software was used for KEGG function annotation. All results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

DMI, milk yield, and milk components

As shown in Fig. 2, the effect of groups and time on milk yield were significant (p < 0.05). Additionally, the milk yield of the SeNPs group was significantly increased (p < 0.01). However, the interaction between SeNPs and time had no significant effect on milk yield (p = 0.44).

As shown in Table 2, compared to the control group, the dry matter intake (DMI) of the SeNPs group was not significantly different. The contents of milk fat and lactose in the SeNPs group were significantly higher than that in the control group (p < 0.05), whereas no significant differences were observed in protein, solids, and non-fat milk solids in goat milk. Additionally, the energy-corrected milk (ECM) of the SeNPs group was significantly higher than that in the CK group (p < 0.05). The ECM calculation formula is as follows31:

A is milk yield (kg), B is fat content (g/kg), C is protein content (g/kg) and D is lactose content (g/kg).

Rumen microbiome 16S rDNA sequencing analysis

The effect of SeNPs on rumen microbial communities

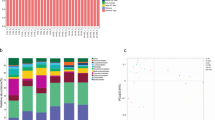

Through sequencing of the 16S rDNA V3-V4 region in the samples, a total of 1,940,626 raw reads were obtained. After quality control and subsequent removal of chimeras and short sequences, a total of 165,7393 sequences were obtained, resulting in the formation of 1,426 OTUs (Fig. 3A). In the control group, there were 1,287 OTUs, with 247 OTUs unique to that group. In the SeNPs group, there were 1,179 OTUs, with 139 OTUs unique to that group. The two groups shared 1,040 OTUs.

The alpha diversity indices are presented in Table 3. The Chao index and ACE index collectively reflect the richness of actual species in a community, with higher values indicating a higher species abundance in the sample. The Shannon index and Simpson index provide an overall assessment of species diversity in a community, with higher values indicating greater species diversity. After the addition of SeNPs, both the Chao index and ACE index showed a downward trend, indicating a decrease in the richness of microorganisms in the rumen. However, there were no statistically significant differences observed in the Shannon index and Simpson index.

Analysis of rumen microbial diversity

Based on the results of OTU annotation, a total of 14 phyla, 22 classes, 41 orders, 48 families, and 78 genera were identified in both groups. As shown in Fig. 3B, at the phylum level, the rumen microbiota of dairy goats was primarily composed of Bacteroidota, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, with Bacteroidota being the dominant phylum. From the overall view of the two groups, the addition of SeNPs resulted in a corresponding decrease of Bacteroidota and Firmicutes in dairy goats, while the proportions of Proteobacteria increased. At the genus level (Fig. 3C), compared to the CK group, the abundance of Prevotella and Rikenellaceae RC9 gut group in the SeNPs group increased, while the abundance of Succiniclasticum decreased. The main dominant microbiota community is shown in Table S1.

Differential microbiota identification

Linear discriminant analysis effect size (Lefse) analysis was conducted based on the annotation information to compare the differences in microbial genus between the two groups, thereby identifying the species significantly enriched after SeNPs treatment. As shown in Fig. 4, in the CK group, a total of 6 significantly different population were identified such as Clostridia vadinBB60 group, Pseudomonadaceae and Pseudomonas (LDA > 2). In the SeNPs group, a total of 4 significantly different population were identified such as UCG 004, Puniceicoccaceae, Opitutales and Verrucomicrobiae (LDA > 2).

Function prediction of differential microbiota

As shown in Fig. 5, Welch’s t-test predicted 13 significantly differently pathways between two groups. The function of rumen microbiota primarily focused on Tryptophan metabolism, Synthesis and degradation of ketone of ketone bodies, Styrene degradation, Lysine degradation and ABC transporters. Additionally, all the significantly different pathways were weakened (p < 0.05) in the SeNPs group.

Effects of SeNPs on rumen microbial metabolism

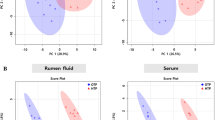

Rumen microbial partial least squares discriminant analysis

As shown in Fig. 6, In both modes, the sample points between the two groups have basically separated, showing a clustered distribution. This indicated that there were certain differences in metabolites between two groups. As shown in Table 4, under the Pos mode, R2X was 0.275, R2Y was 0.927, and Q2 was 0.566. Under the Neg mode, R2X was 0.322, R2Y was 0.992, and Q2 was 0.664, indicating that the predictive ability of this model is reliable.

The effects of SeNPs on the rumen metabolites

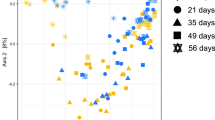

Screening of differential metabolites between two groups was conducted by combining univariate statistical analysis and multivariate statistical analysis (with the criteria being VIP ≥ 1 and T-test P < 0.05). The hierarchical clustering heat map of differential metabolites is shown in Fig. 7. As shown in the volcano diagram of differential metabolites (Fig. 8) and Table S2, under the positive ion mode, a total of 95 differential metabolites were identified, with 27 being upregulated and 68 downregulated. Under the negative ion mode, 24 differential metabolites were detected, with 6 upregulated and 18 downregulated.

Metabolic pathway analysis of differential metabolites

After identifying all the differential metabolites, the KEGG metabolic pathway enrichment was carried out. All of the differential metabolites were enriched in 46 metabolic pathways. The top 20 pathways with the smallest p-value, are shown in a scatter plot (Fig. 9) and Supplementary Table S3. Only the pathway of Glutathione metabolism was significantly enriched (p < 0.05), among all the 46 metabolic pathways. The three pathways, which is Naphthalene family (p = 0.05), Biosynthesis of alkaloids derived from ornithine, lysine and nicotinic acid (p = 0.07) and ABC transporters (p = 0.07) exhibited a significant enrichment trend.

The top 20 metabolic pathways of KEGG enrichment. The vertical coordinate is the pathway and the horizontal coordinate is the enrichment factor, which is the proportion of differential metabolites in that pathway to the total metabolites in that pathway. Size indicates how much quantity of differential metabolites. Color represents Q-value, the darker the color, the more significant the results. KEGG pathway data were sourced from the KEGG database: www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html.

Correlation of lactation and rumen metabolites with rumen microbiota

The correlation between all the 18 differential rumen microbiota species and milk yield and components was analyzed using the Pearson correlation analysis. As shown in Table 5, Succinivibrio dextrinosolvens is significantly positively correlated with milk protein and solids. Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens is significantly positively correlated with milk solids and non-fat milk solids. Rummeliibacillus pycnus was significantly negatively correlation with lactose content. Ralstonia insidiosa exhibited a significant positive correlation with lactose content. Prevotella sp BP1-56 exhibited a positive correlation with milk fat content.

The correlation of all the 18 differential rumen microbiota species and defferentially metabolites was performed using the Pearson correlation analysis. As shown in Fig. 10, Prevotella ruminicola 23, a member of Prevotella, was significantly negatively correlated with Trp-cys in Pyrimidine metabolism products and significantly positively correlated with Tropinone in Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites products. Ruminococcus sp, a member of the Ruminococcus, was significantly positively correlated with the L-Lysine in Lysine biosynthesis products. Ralstonia insidiosa was significantly positively correlated with L-glutathione, 2’-deoxycytidine, Homogentisic acid, L-glutathione, and metanephrine, but significantly negatively correlated with gamma-glu-cys. In summary, Prevotella ruminicola 23 primarily affects the enrichment of metabolites such as Trp-cys, Tropinone, and Adrenosterone, thereby influencing Nucleotide metabolism and Lipid metabolism. Ruminococcus sp, and Ralstonia insidiosa mainly affect the differential metabolites, such as L-lysine, metanephrine, and L-glutathione, thereby regulating Amino acid metabolism.

Discussion

Heat stress not only affects animal growth and reproduction but also negatively impacts the quality of dairy and egg products32,33. Under heat stress conditions, milk yield and protein content in dairy cows significantly decrease, and butterfat percentage may also change, affecting the quality and economic value of dairy products34. Similarly, in poultry, high-temperature environments reduce egg production rates and negatively influence eggshell quality as well as yolk and egg white properties35. In recent years, SeNPs has emerged as a novel selenium supplement due to its higher bioavailability and lower toxicity, becoming a feed additive to improve animal production performance23. Supplementation of selenium in dairy cow diets can enhance antioxidant status, improve feed intake under heat stress, increase feed digestibility, and ultimately boost milk yield36. In this study, dietary supplementation of SeNPs increased the milk yield of dairy goats, suggesting a positive impact on milk yield. This phenomenon may be attributed to the small particle size of SeNPs, which facilitates absorption in the small intestine, thereby increasing the expression of selenium-related proteins in the mammary glands and promoting milk yield37,38. Additionally, related research have confirmed that supplementation with selenium yeast or hydroxy-selenomethionine (OH-SeMet) effectively improves milk yield in mid-to-late lactation stages in dairy cows39. Selenium supplementation has also been shown to increase the distribution area of breast capillaries in mammary glands, further promoting milk yield40.Lactose is a key indicator of lactation activity, and its synthesis quantity and efficiency are positively correlated with milk yield41. In this study, dietary supplementation with SeNPs significantly increased lactose and milk fat content, but had no significant effect on milk protein content. Some studies suggest that selenium supplementation can increase the relative content of lactose and milk fat42,43, while others indicate that it may reduce milk protein content44. However, other research suggests that selenium supplementation has no significant impact on milk composition45. These discrepancies may be related to the form and dosage of selenium supplementation. In summary, under heat stress conditions, nano-selenium as a novel selenium supplementation form improves bioavailability and antioxidant status, effectively enhancing milk yield in dairy goats. However, its impact on milk quality remains controversial, necessitating further research to optimize supplementation strategies and elucidate the action mechanisms.

Selenium is one of the essential trace elements for the body, playing a positive role in maintaining intestinal health and promoting the growth of beneficial microorganisms. Studies have shown that SeNPs can improve gut health by regulating the composition of intestinal microbiota, thereby maintaining the balance of the gut microbial community46. In this study, dietary supplementation with SeNPs under heat stress conditions significantly affected the rumen microbial community structure of dairy goats. Dynamic changes in the diversity and composition of rumen microbiota can impact the digestion and absorption of nutrients47. In our study, the dominant bacterial phyla in the rumen of dairy goats were Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, consistent with previous findings48. Prevotella is a core microbiota responsible for carbohydrate and hydrogen metabolism. It has the ability to efficiently degrade cellulose through cellulase and produce short-chain fatty acids, thus protecting the host’s gut health11,49. However, related research have found that heat stress significantly reduced the relative abundance of Prevotella and the concentrations of certain organic acids in the rumen of beef cattle50. Dietary supplementation with hydroxy-selenomethionine significantly increased the relative abundance of Prevotella in the rumen of dairy cows51. In this study, dietary supplementation with SeNPs significantly increased the relative abundance of Prevotella, indicating that SeNPs may improve the fiber digestion capacity of dairy goats by increasing the relative abundance of Prevotella, thereby enhancing their production performance under heat stress. Notably, under heat stress conditions, the relative abundance of Succiniclasticum, an important member of the core microbiota in the rumen of ruminants, significantly increases52. Succiniclasticum primarily participates in starch degradation53; however, its excessive abundance may inhibit nitrogen absorption and degradation in animals54,55. In our study, dietary supplementation with SeNPs significantly reduced the relative abundance of Succiniclasticum, indicating that SeNPs can suppress the proliferation of Succiniclasticum under high temperatures, thereby improving energy absorption and production performance during heat stress. Additionally, the relative abundance of Ruminococcus, a key genus involved in cellulose degradation, significantly decreases under heat stress56. However, studies on mice fed selenium-enriched spirulina have shown that selenium-enriched spirulina significantly increases the abundance of Ruminococcus57. In this study, supplementation with SeNPs showed similar results, indicating that dietary SeNPs effectively increase the relative abundance of Ruminococcus under heat stress, thereby enhancing the fiber degradation capacity of the goat rumen. In summary, dietary supplementation with SeNPs not only significantly increased the relative abundance of Prevotella and Ruminococcus in the rumen but also significantly reduced the relative abundance of Succiniclasticum. This improved the rumen’s ability to degrade fiber and starch in dairy goats, effectively mitigating the damage caused by heat stress. These findings provide theoretical support for further exploring the application of SeNPs in the management of heat stress in ruminants.

Dietary supplementation with SeNPs not only improved the composition of the rumen microbiota in dairy goats under heat stress but also had significant effects on metabolism. Heat stress can lead to abnormal fat metabolism in animals, increase lipid oxidation, and disrupt lipid metabolic homeostasis58,59. It has been reported that dietary supplementation with selenium yeast enhances lipid metabolism by increasing the level of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) in pigs60. Lysine, as an essential amino acid, plays a critical role in carnitine synthesis, and fluctuations in its levels can affect lipid metabolism61. Furthermore, lysine can influence fat deposition by regulating the expression of fatty acid-binding protein 1 (FABP1) in the liver62. During heat stress, lysine levels in animals significantly decline63. However, in this study, dietary supplementation with SeNPs increased lysine levels, which were significantly enriched in the biosynthetic pathways of ABC transporters, ornithine, lysine, and niacin-derived alkaloids. This indicates that SeNPs supplementation helps upregulate lysine levels, potentially improving lipid metabolism and enhancing the health of dairy goats under heat stress. Heat stress also downregulates glutathione metabolism, leading to a decrease in glutathione levels in animals during lactation, thereby inducing oxidative stress64,65. The synthesis of glutathione can prevent oxidative stress-induced damage to mammary epithelial cells and maintain normal mammary tissue function66. Related studies have shown that dietary selenium supplementation significantly upregulates glutathione metabolism levels in sheep67. In this study, dietary supplementation with SeNPs increased the level of putrescine, which was significantly enriched in the glutathione metabolic pathway. Putrescine is the primary precursor of spermidine, which is positively correlated with milk yield68. This suggests that dietary supplementation with SeNPs can enhance glutathione metabolism by increasing putrescine levels, potentially improving the antioxidant capacity of dairy goats. In conclusion, SeNPs influence metabolic pathways by regulating metabolic products, enhancing the antioxidant capacity of dairy goats under heat stress, and improving the stability of their physiological functions.

It has been reported that rumen bacteria are closely correlated with milk composition69. Under heat stress conditions, the redistribution of nutrients in animals leads to a reduction in precursors (glucose and amino acids) for casein (the main component of milk protein) in the mammary glands, thereby decreasing milk protein content70. Relevant studies have shown that populations of the genus Succinivibrio sp are positively correlated with feed efficiency in beef cattle71 and dairy cows72. This is mainly because Succinivibrio can produce succinate (a precursor of propionate), which influences hepatic gluconeogenesis and provides the glucose necessary for lactation, thus impacting milk yield efficiency. In this study, Succinivibrio dextrinosolvens, a member of the Succinivibrio genus, was positively correlated with milk protein content, consistent with previous research findings73. This may be because Succinivibrio dextrinosolvens indirectly increases the concentration of propionate by producing succinate, thereby providing more glucose precursors for the synthesis of milk proteins in the mammary gland. However, this mechanism requires further experimental validation. Although Prevotella can increase the concentrations of volatile fatty acids (VFAs, including acetate, propionate, and valerate) and improve overall feed efficiency73, it is negatively correlated with milk fat content74,75. Some studies have indicated that certain Prevotella taxa (such as Prevotellaceae UCG-001 and Prevotellaceae UCG-003) are positively correlated with milk fat content. This may be due to their positive association with key substrates for milk fat synthesis (such as acetate) and the more detailed classification involved76,77. In this study, Prevotella sp BP1-56 was negatively correlated with milk fat content, which could be attributed to differences in metabolic pathways or interactions with the host. Specifically, different strains may vary in their ability to produce key substrates such as acetate, leading to different effects on milk fat.

In this study, correlation analysis revealed the complex relationships between microbial communities and differential metabolites, further emphasizing the potential application value of microbial communities in animal production. Heat stress can compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier in animals, increasing the permeability of intestinal epithelial cells and triggering oxidative stress responses, which negatively impact animal health78. As a major anti-inflammatory component, propofol effectively alleviates intestinal inflammation caused by heat stress by inhibiting the expression of inflammation-related genes and promoting the expression of tight junction proteins in the intestine79. This study found that dietary supplementation with selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) significantly increased the relative content of propofol, which was positively correlated with Rumen bacterium R-21. Notably, there is limited research in the existing literature on the correlation between propofol and specific microbial communities, likely due to the high level of bacterial classification detail and the scarcity of studies covering such specific associations. Future research could further explore the interaction mechanisms between propofol and Rumen bacterium R-21. Additionally, selenium supplementation in diets is widely recognized for increasing glutathione (GSH) levels in animals. By catalyzing GSH metabolism, it helps maintain redox balance in the body, reduces intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, and alleviates the negative effects of oxidative stress on animal health80,81,82. In this study, dietary supplementation with SeNPs not only significantly increased the relative content of propofol but also reduced the relative abundance of the harmful bacterium Ralstonia insidiosa. This change was correlated with an increased relative content of γ-glutamylcysteine (γ-Glu-Cys), a precursor of GSH. Correlation analysis revealed that Ralstonia insidiosa was significantly negatively correlated with γ-Glu-Cys. This suggests that dietary supplementation with SeNPs may enhance the body’s antioxidant capacity by regulating the abundance of Ralstonia insidiosa and its correlated metabolites. These findings further demonstrate the regulatory role of SeNPs in animal metabolism and provide scientific evidence for optimizing selenium supplementation strategies in diets.

Conclusions

The results indicated that dietary supplementation with SeNPs improved milk yield and quality in dairy goats under heat stress conditions. Dietary supplementation with SeNPs positively influenced the composition and abundance of rumen microbiota and improved the rumen metabolism. Many differential microbes and differential metabolites were correlated with milk yield and milk quality. This intervention is advantageous for maintaining a more stable rumen microbial ecosystem, which in turn further improves rumen health and lactation performance in dairy goats, particularly under conditions of heat stress.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the primary accession code PRJNA1170429.

References

Bejaoui, B. et al. Physicochemical properties, antioxidant markers, and meat quality as affected by heat stress: A review. Molecules https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28083332 (2023).

Ghulam Mohyuddin, S. et al. Influence of heat stress on intestinal epithelial barrier function, tight junction protein, and immune and reproductive physiology. Biomed. Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8547379 (2022).

Rathwa, S. D. et al. Effect of season on physiological, biochemical, hormonal, and oxidative stress parameters of indigenous sheep. Vet. World 10, 650–654. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2017.650-654 (2017).

Sejian, V., Bhatta, R., Gaughan, J. B., Dunshea, F. R. & Lacetera, N. Review: Adaptation of animals to heat stress. Animal 12, S431–S444. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1751731118001945 (2018).

Ellett, M. D. et al. Relationships between gastrointestinal permeability, heat stress, and milk production in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 107, 5190–5203. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2023-24043 (2024).

Yadav, S. & Jha, R. Strategies to modulate the intestinal microbiota and their effects on nutrient utilization, performance, and health of poultry. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-018-0310-9 (2019).

Kvidera, S. K. et al. Intentionally induced intestinal barrier dysfunction causes inflammation, affects metabolism, and reduces productivity in lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 100, 4113–4127. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-12349 (2017).

Kvidera, S. K. et al. Glucose requirements of an activated immune system in lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 100, 2360–2374. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-12001 (2017).

He, J. et al. Heat stress affects fecal microbial and metabolic alterations of primiparous sows during late gestation. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-019-0391-0 (2019).

Liu, C. et al. Dynamic alterations in yak rumen bacteria community and metabolome characteristics in response to feed type. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01116 (2019).

Lorena Betancur-Murillo, C., Bibiana Aguilar-Marin, S. & Jovel, J. Prevotella: A key player in ruminal metabolism. Microorganisms https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11010001 (2023).

Kieliszek, M. Selenium-fascinating microelement, properties and sources in food. Molecules https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24071298 (2019).

Xu, C., Qiao, L., Guo, Y., Ma, L. & Cheng, Y. Preparation, characteristics and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides and proteins-capped selenium nanoparticles synthesized by Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393. Carbohydr. Polym. 195, 576–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.110 (2018).

Helke, K. L. et al. Mulberry heart disease and hepatosis dietetica in farm pigs (sus scrofa domesticus) in a research setting. Comp. Med. 70, 376–383. https://doi.org/10.30802/aalas-jaalas-19-000162 (2020).

Jelinek, P. et al. The effect of selenium supplementation on immunity, and the establishment of an experimental haemonchus contortus infection, in weaner Merino sheep fed a low selenium diet. Asut. Vet. J. 65, 214–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.1988.tb14461.x (1988).

Pecoraro, B. M. et al. The health benefits of selenium in food animals: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-022-00706-2 (2022).

Zhang, Z. D. et al. Effects of sodium selenite and coated sodium selenite on lactation performance, total tract nutrient digestion and rumen fermentation in Holstein dairy cows. Animal 14, 2091–2099. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1751731120000804 (2020).

Cui, X. et al. Selenium yeast dietary supplement affects rumen bacterial population dynamics and fermentation parameters of tibetan sheep (ovis aries) in alpine meadow. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.663945 (2021).

Zheng, Y. et al. Effects of selenium as a dietary source on performance, inflammation, cell damage, and reproduction of livestock induced by heat stress: a review. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.820853 (2022).

Khalil, M. M. H. et al. Comparison of dietary supplementation of sodium selenite and bio-nanostructured selenium on nutrient digestibility, blood metabolites, antioxidant status, milk production, and lamb performance of Barki ewes. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2023.115592 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Recent research progress on the synthesis and biological effects of selenium nanoparticles. Front. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1183487 (2023).

Rehman, H. F. et al. Effect of selenium nanoparticles and mannan oligosaccharide supplementation on growth performance, stress indicators, and intestinal microarchitecture of broilers reared under high stocking density. Animals https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12212910 (2022).

Malyugina, S., Skalickova, S., Skladanka, J., Slama, P. & Horky, P. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles in animal nutrition: A review. Agric. Basel https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11121244 (2021).

Samo, S. P. et al. Supranutritional selenium level minimizes high concentrate diet-induced epithelial injury by alleviating oxidative stress and apoptosis in colon of goat. BMC Vet. Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02653-4 (2020).

Zarczynska, K., Brym, P. & Tobolski, D. The role of selenitetriglycerides in enhancing antioxidant defense mechanisms in peripartum holstein-friesian cows. Animals https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14040610 (2024).

du Sert, N. P. et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411 (2020).

Habeeb, A. A., Gad, A. E. & Atta, M. A. Temperature-humidity indices as indicators to heat stress of climatic conditions with relation to production and reproduction of farm animals. Int. J. Biotechnol. Recent Adv. 1, 35–50. https://doi.org/10.18689/ijbr-1000107 (2018).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. J. N. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. J. N. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. J. P. S. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Prot. Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Li, B. et al. Genetic heterogeneity of feed intake, energy-corrected milk, and body weight across lactation in primiparous Holstein, Nordic Red, and Jersey cows. J. Dairy Sci. 101, 10011–10021. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-14611 (2018).

Alagawany, M., Farag, M. R., Abd El-Hack, M. E. & Patra, A. Heat stress: effects on productive and reproductive performance of quail. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 73, 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043933917000782 (2017).

Chen, S., Yong, Y. & Ju, X. Effect of heat stress on growth and production performance of livestock and poultry: Mechanism to prevention. J. Therm. Biol https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.103019 (2021).

Gorniak, T., Meyer, U., Suedekum, K.-H. & Daenicke, S. Impact of mild heat stress on dry matter intake, milk yield and milk composition in mid-lactation Holstein dairy cows in a temperate climate. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 68, 358–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/1745039x.2014.950451 (2014).

Kim, H.-R., Ryu, C., Lee, S.-D., Cho, J.-H. & Kang, H. Effects of heat stress on the laying performance, egg quality, and physiological response of laying hens. Animals https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14071076 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Effects of selenium yeast on rumen fermentation, lactation performance and feed digestibilities in lactating dairy cows. Livest. Sci. 126, 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2009.07.005 (2009).

Shi, L. et al. Effect of sodium selenite, se-yeast and nano-elemental selenium on growth performance, se concentration and antioxidant status in growing male goats. Small Rumin. Res. 96, 49–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2010.11.005 (2011).

Xiao, M. et al. Effects of nanoselenium on the performance, blood indices, and milk metabolites of dairy cows during the peak lactation period. Front. Vet. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2024.1418165 (2024).

Hachemi, M. A., Sexton, J. R., Briens, M. & Whitehouse, N. L. Efficacy of feeding hydroxy-selenomethionine on plasma and milk selenium in mid-lactation dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 106, 2374–2385. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-22323 (2023).

Vonnahme, K. A. et al. Supranutritional selenium increases mammary gland vascularity in postpartum ewe lambs. J. Dairy Sci. 94, 2850–2858. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2010-3832 (2011).

Tong, M. et al. Effects of dietary selenium yeast supplementation on lactation performance, antioxidant status, and immune responses in lactating donkeys. Antioxidants https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13030275 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Effects of nanoselenium supplementation on lactation performance, nutrient digestion and mammary gland development in dairy cows. Anim. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495398.2023.2290526 (2024).

Miglior, F. et al. Genetic analysis of milk urea nitrogen and lactose and their relationships with other production traits in Canadian Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 90, 2468–2479. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2006-487 (2007).

Calamari, L., Petrera, F. & Bertin, G. Effects of either sodium selenite or se yeast (Sc CNCM I-3060) supplementation on selenium status and milk characteristics in dairy cows. Livest. Sci. 128, 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2009.12.005 (2010).

Juniper, D. T., Phipps, R. H., Jones, A. K. & Bertin, G. Selenium supplementation of lactating dairy cows: Effect on selenium concentration in blood, milk, urine, and Feces. J. Dairy Sci. 89, 3544–3551. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72394-3 (2006).

Qiao, L. et al. Replacing dietary sodium selenite with biogenic selenium nanoparticles improves the growth performance and gut health of early-weaned piglets. Anim. Nutr. 15, 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2023.08.003 (2023).

Bailoni, L., Carraro, L., Cardin, M. & Cardazzo, B. Active rumen bacterial and protozoal communities revealed by RNA-based amplicon sequencing on dairy cows fed different diets at three physiological stages. Microorganisms https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9040754 (2021).

Bibiana Aguilar-Marin, S., Lorena Betancur-Murillo, C., Isaza, G. A., Mesa, H. & Jovel, J. Lower methane emissions were associated with higher abundance of ruminal Prevotella in a cohort of Colombian buffalos. BMC Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-020-02037-6 (2020).

Schofield, B. J. et al. Beneficial changes in rumen bacterial community profile in sheep and dairy calves as a result of feeding the probiotic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57. J. Appl. Microbiol. 124, 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13688 (2018).

Correia Sales, G. F. et al. Heat stress influence the microbiota and organic acids concentration in beef cattle rumen. J. Therm. Biol https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.102897 (2021).

Wang, N. et al. Supplementation of micronutrient selenium in metabolic diseases: its role as an antioxidant. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7478523 (2017).

Zou, B. et al. Alleviation effects of niacin supplementation on beef cattle subjected to heat stress: a metagenomic insight. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.975346 (2022).

Jin, Y. et al. Effects of replacing hybrid giant napier with sugarcane bagasse and fermented sugarcane bagasse on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, rumen fermentation characteristics, and rumen microorganisms of Simmental crossbred cattle. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1236955 (2023).

Pan, C. et al. Dietary supplementation with bupleuri radix reduces oxidative stress occurring during growth by regulating rumen microbes and metabolites. Animals https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14060927 (2024).

Wang, J., Zhao, G., Zhuang, Y., Chai, J. & Zhang, N. Yeast (saccharomyces cerevisiae) culture promotes the performance of fattening sheep by enhancing nutrients digestibility and rumen development. Ferment. Basel https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8120719 (2022).

Liu, W.-C., Huang, M.-Y., Balasubramanian, B. & Jha, R. Heat stress affects jejunal immunity of yellow-feathered broilers and is potentially mediated by the microbiome. Front. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.913696 (2022).

Zhou, N. et al. Selenium-containing polysaccharide from spirulina platensis alleviates Cd-induced toxicity in mice by inhibiting liver inflammation mediated by gut microbiota. Front. Nutr. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.950062 (2022).

Guo, Y., Balasubramanian, B., Zhao, Z.-H. & Liu, W.-C. Heat stress alters serum lipid metabolism of Chinese indigenous broiler chickens-a lipidomics study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 10707–10717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11348-0 (2021).

Slimen, I. B., Najar, T., Ghram, A. & Abdrrabba, M. Heat stress effects on livestock: Molecular, cellular and metabolic aspects, a review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 100, 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpn.12379 (2016).

Zhang, K. et al. Targeted metabolomics analysis reveals that dietary supranutritional selenium regulates sugar and acylcarnitine metabolism homeostasis in pig liver. J. Nutr. 150, 704–711. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxz317 (2020).

Huang, D. et al. Effects of dietary lysine levels on growth performance, whole body composition and gene expression related to glycometabolism and lipid metabolism in grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idellus fry. Aquaculture https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735806 (2021).

Tian, D. L. et al. Effects of lysine deficiency or excess on growth and the expression of lipid metabolism genes in slow-growing broilers. Poult. Sci. 98, 2927–2932. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pez041 (2019).

Ma, B. et al. Heat stress alters muscle protein and amino acid metabolism and accelerates liver gluconeogenesis for energy supply in broilers. Poult. Sci. 100, 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2020.09.090 (2021).

Eslamizad, M., Albrecht, D. & Kuhla, B. The effect of chronic, mild heat stress on metabolic changes of nutrition and adaptations in rumen papillae of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 103, 8601–8614. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2020-18417 (2020).

Garhwal, R. et al. Comparative metabolomics analysis of Halari donkey colostrum and mature milk throughout lactation stages using 1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2023.114805 (2023).

Meng, L. et al. Dietary selenium levels affect mineral absorbability, rumen fermentation, microbial composition and metabolites of the grazing sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2024.115877 (2024).

Kannan, N. et al. Glutathione-dependent and independent oxidative stress-control mechanisms distinguish normal human mammary epithelial cell subsets. PNAS 111, 7789–7794. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1403813111 (2014).

Buts, J. P. Milk-borne bioactive factors. Archives De Pediatrie 5, 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0929-693x(97)89374-8 (1998).

Zeng, H., Guo, C., Sun, D., Seddik, H.-E. & Mao, S. The ruminal microbiome and metabolome alterations associated with diet-induced milk fat depression in dairy cows. Metabolites https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9070154 (2019).

Guo, Z., Gao, S., Ouyang, J., Ma, L. & Bu, D. Impacts of heat stress-induced oxidative stress on the milk protein biosynthesis of dairy cows. Animals https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030726 (2021).

Hernandez-Sanabria, E. et al. Impact of feed efficiency and diet on adaptive variations in the bacterial community in the rumen fluid of cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.05114-11 (2012).

Elolimy, A. A., Arroyo, J. M., Batistel, F., Iakiviak, M. A. & Loor, J. J. Association of residual feed intake with abundance of ruminal bacteria and biopolymer hydrolyzing enzyme activities during the peripartal period and early lactation in Holstein dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-018-0258-9 (2018).

Xue, M. Y., Sun, H. Z., Wu, X. H., Guan, L. L. & Liu, J. X. Assessment of rumen bacteria in dairy cows with varied milk protein yield. J. Dairy Sci. 102, 5031–5041. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-15974 (2019).

Jami, E., White, B. A. & Mizrahi, I. Potential role of the bovine rumen microbiome in modulating milk composition and feed efficiency. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085423 (2014).

Si, B. et al. Relationship between rumen bacterial community and milk fat in dairy cows. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1247348 (2023).

Liu, K. et al. Ruminal bacterial community is associated with the variations of total milk solid content in Holstein lactating cows. Anim. Nutr. 9, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2021.12.005 (2022).

Xue, M.-Y., Sun, H.-Z., Wu, X.-H., Liu, J.-X. & Guan, L. L. Multi-omics reveals that the rumen microbiome and its metabolome together with the host metabolome contribute to individualized dairy cow performance. Microbiome https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00819-8 (2020).

Furness, J. B., Rivera, L. R., Cho, H.-J., Bravo, D. M. & Callaghan, B. The gut as a sensory organ. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 729–740. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2013.180 (2013).

Yue, M. et al. Protopine alleviates dextran sodium sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis by improving intestinal barrier function and regulating intestinal microbiota. Molecules https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28135277 (2023).

Baba, S. P. & Bhatnagar, A. Role of thiols in oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 7, 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cotox.2018.03.005 (2018).

Hoffman, D. J. & Heinz, G. H. Effects of mercury and selenium on glutathione metabolism and oxidative stress in Mallard ducks. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 17, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620170204 (1998).

Leboeuf, R. A. & Hoekstra, W. G. Adaptive changes in hepatic glutathione metabolism in response to excess selenium in rats. J. Nutr. 113, 845–854. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/113.4.845 (1983).

Funding

This research was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation in China (2023M740414). The Chongqing Natural Science Foundation in China (CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX1098). The Youth Project of Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Education Commission in China (KJQN202201350). The Tower Foundation Program of Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences in China (R2022YS08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. Y. and S.X. were responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, and writing the original draft. Z. X developed the methodology. Y. S., Q. Y. and H.G. handled visualization. W. F. oversaw conceptualization, project administration and writing—review and editing. Y. W. oversaw conceptualization, project administration, writing—review and editing and funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ying, Z., Xie, S., Xiu, Z. et al. Under heat stress conditions, selenium nanoparticles promote lactation through modulation of rumen microbiota and metabolic processes in dairy goats. Sci Rep 15, 9063 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93710-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93710-1