Abstract

Tear hyperosmolarity plays a crucial role in initiation of inflammatory response and damage to ocular surface epithelia. Accurate measurement of tear osmolarity is essential for dry eye. This prospective observational and experimental study was conducted in 182 eyes of 182 participants, including 115 subjects with dry eye (Sjögren syndrome aqueous-deficient dry eye [SS ADDE], non-SS ADDE, and evaporative DE [EDE]), 36 with conjunctivochalasis (CCh), and 31 normal controls (NC). The ocular surface disease index (OSDI), tear meniscus height (TMH), Schirmer I test, tear matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), tear breakup time, and ocular staining score were assessed. Tear osmolarity was measured using the TearLab osmolarity system (Escondido, CA, USA) by applying 1.0 μl tears collected by micropipette to the TearLab test card or by direct contact between the test card and the temporal tear meniscus. For in vitro analyses, osmolarity of 271.25, 300, 347.5, and 395 mOsm/L solutions were measured at various volumes (0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 5.0 μl) with a TearLab osmometer. Tear osmolarity measured by direct contact was higher than that measured by micropipette (13.7 ± 10.5 mOsm/L, p < 0.001). The difference of osmolarities was higher in the non-SS ADDE, SS ADDE, and CCh than in the NC and EDE (p < 0.001 for all). Osmolarity was negatively correlated with Schirmer score and TMH (r = − 0.346, p < 0.001; r = − 0.447, p < 0.001, respectively). The smaller the sample volume, the higher the measured osmolarity in the in vitro analysis at 300 and 347.5 mOsm/L (r = − 0.659, p < 0.01; r = − 0.579, p < 0.05, respectively). The TearLab osmometer tended to report higher tear osmolarity inversely proportional to sample volumes, possibly due to the evaporation effect. Therefore, care should be taken when interpreting tear osmolarity in patients with low tear volume or CCh.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, the research efforts were attempted to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms and etiology of dry eye disease (DED)1. The National Eye Institute/industry Dry Eye Workshop concluded that dry eye (DE) can originate from multiple diseases and sought to define DE through classification of these diseases1. The initial National Eye Institute/industry workshop defined only two primary categories of DE: tear-deficient and evaporative2. In 2007, the International Dry Eye WorkShop (DEWS) concluded that tear meniscus hyperosmolarity and ocular surface inflammation are core pathologic mechanisms of DE1,3. In addition, the DEWS II pathophysiology report emphasized that tear meniscus hyperosmolarity plays a role in the vicious cycle in DE, together with tear film instability, ocular surface inflammation, and ocular surface damage4. These pathological mechanisms cause DE patients to enter a self-perpetuating loop4. Thus, the role of tear hyperosmolarity in the pathogenesis of DE has continuously evolved.

Tear osmolarity is determined by dissolved electrolytes within the tears, which are actively adjusted by secretion, evaporation, and drainage5,6. Due to the tear dynamics, the spatial distribution of tear osmolarity varies across the preocular surface, influenced by differences in structure, volume, and thickness in various areas7,8. Tear osmolarity varies significantly between the lower meniscus and the precorneal tear film, exhibiting dynamic spatial and temporal fluctuations across the cornea9,10. In particular, tear osmolarity is expected to rise in tear “break-up” areas due to water evaporation and solute retention, as governed by the law of conservation of mass11.

Various studies have reported pathologic changes caused by tear hyperosmolarity12,13,14,15,16. In in vitro studies, hyperosmolarity disrupts the cell membrane, weakens cell tight junctions, and causes cellular swelling12,13,14. In addition, in vivo studies have identified that increased tear meniscus osmolarity results in epithelial cell desquamation, conjunctival goblet cell apoptosis, and damage to the sub-basal nerve plexus15,16. Hyperosmolar stress initiates the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, activating nuclear factor-kappa B signaling6,17,18. Finally, hyperosmotic tear meniscus activates ocular surface inflammation by stimulating corneal nerve endings15,19.

As tear meniscus hyperosmolarity has been proposed as a core mechanism of DE pathology, measuring tear meniscus osmolarity has thus emerged as a crucial and objective diagnostic tool for DE1,4,20,21. Nevertheless, clinical measurement of the tear meniscus osmolarity has been hindered by procedural difficulties, such as extremely small sample volume. Prior to the advent of the TearLab osmometer, ex vivo methods using freezing point depression or vapor-pressure osmometer after collecting tears using a micropipette or microtube were used22,23,24. Despite the high sensitivity of these methods, 4–10 μl sample volume is needed to measure osmolarity using these osmometers. Because the entire tear volume averages 7–8 μl in normal eyes, and 4.8 μl in Sjögren syndrome eyes, dilution is essential after obtaining tear samples25. During these complex procedures, pipetting errors could be introduced in the sampling or dilution of tears. Due to the timely nature of the procedures, the aqueous component of the tear sample evaporates, which could potentially lead to an overestimation of tear osmolarity26. Therefore, this complex procedure was difficult to utilize in clinical practice because in-office detection was infeasible.

According to the US patent for tear meniscus osmometry (Patent No. US 8,713,997 B2), the TearLab™ osmolarity system measures electrical conductivity on an aliquot-sized sample placed onto a sample-receiving chip. Using this system, conductivity can be measured in samples as small as 50 nl. The TearLab osmometer estimates the osmolarity value from the calibrated standard curve between electrical conductivity, measured by electrodes placed on the microcapillary of the TearLab test card, and sodium chloride concentration. The TearLab corporation suggested that since the impedance value is independent of sample volume, tear meniscus osmolarity measurement by the Tear Lab osmolarity system is not limited by tear sample volume. After DEWS redefined DE in 20071, the introduction of the TearLab osmolarity system using this new concept measurement enabled the clinicians to use this point-of-care test in diagnosis/assessment of DE in clinical practice. After the emergence of the new point-of-care osmometer, many studies have reported its utility, consistency, and accuracy27,28. Nevertheless, other studies have reported high variability of tear osmolarity measurement by this instrument in DE patients, meriting careful interpretation of findings in context with other test results and symptoms29,30,31,32. A report by Szczesna-Iskander et al. highlighted that the TearLab osmometer exhibited variability in its results, underscoring the importance of conducting multiple measurements to ensure consistency30. Moreover, in comparison to the freezing point osmometer, previous studies have documented both concordance22,33 and discrepancy26 in tear film osmolarity measurements using the TearLab osmometer.

Given the variability in tear volume among DE patients due to their underlying mechanisms, this study aimed to evaluate whether tear sample volume influences the readings of the TearLab osmolarity system through a combination of in vivo and in vitro studies.

Results

Study population

Demographic information for each group is shown in Table 1. A total of 115 DE (115 eyes) patients, 31 normal controls (NC, 31 eyes), and 36 conjunctivochalasis (CCh, 36 eyes) patients were enrolled in the study. The laterality of measured (enrolled) eyes in the study was 55.5% for the right eye and 44.5% for the left eye. DE groups consisted of 48 evaporative dry eye (EDE) and 67 aqueous-deficient dry eye (ADDE) cases. ADDE was subdivided as 34 non-Sjögren syndrome (non-SS) ADDE and 33 SS ADDE.

Group comparisons

The ocular surface disease index (OSDI) score was highest in the ADDE subgroups (non-SS and SS) and lowest in the NC group (p = 0.036). The OSDI score of non-SS ADDE was significantly higher than that of the control group (p = 0.048). The tear breakup time (tBUT) did not significantly differ between the EDE, non-SS ADDE, and SS ADDE groups. The tBUT of NC and CCh were longer than those of all DE groups (p < 0.001). The Schirmer test results did not differ between ADDE subgroups (non-SS and SS), and both non-SS and SS ADDE values were lower than those of the NC, EDE, and CCh groups (p < 0.001). The ocular staining score (OSS) by Oxford scheme was significantly higher in the SS ADDE subgroup relative to other subgroups (p < 0.001). The mean and standard deviation values are summarized in Table 2.

In vivo results

Mean OSMdirect and OSMpipette from all participants significantly differed between methods (OSMdirect 309.3 ± 11, OSMpipette 295.5 ± 16.0 mOsm/L; p < 0.001). Comparisons between OSMdirect and OSMpipette revealed that tear meniscus osmolarity values measured by OSMdirect were significantly higher than those measured by OSMpipette in all groups (p < 0.001). In addition, posthoc comparisons within OSMpipette showed no difference between any of the five subgroups (p = 0.968), but OSMdirect was significantly different between subgroups (p < 0.001). The degree of difference (OSMdiff) was significantly higher in the ADDE subgroups and CCh groups relative to NC or EDE (p < 0.001). There was no difference between ADDE subgroups and CCh (non-SS ADDE vs CCh: p = 0.906; SS ADDE vs CCh: p = 0.373; non-SS vs SS ADDE: p = 0.888). The mean values and standard deviations of all groups are summarized in Table 3, and the post hoc analysis are shown in Table 4.

Correlations of ocular surface parameters and osmolarity

Correlation analyses of ocular surface parameters and both OSMdirect and OSMpipette measurements were performed in all participants and did not reveal a significant correlation between OSMpipette and ocular surface parameters, with exception of cornea OSS (R = 0.156, p = 0.035). However, OSMdirect were significantly correlated with multiple ocular surface parameters. The Schirmer test and tear meniscus height (TMH) showed negative correlation with OSMdiff in patients with CCh (R = − 0.276, p < 0.001 and R = − 0.347, p < 0.001, respectively). This correlation was also found in patients without CCh. (R = -0.346, p < 0.001 and R = − 0.447, p < 0.001, respectively). Detailed results of correlation analyses are summarized in Table 5.

In vitro results

Measured osmolarity increased as applied volumes decreased, especially statistically significant in 300 and 347.5 mOsm/L (r = − 0.659, p < 0.01; r = − 0.579, p < 0.05, respectively). (Table 6) Applications of 395 mOsm/L test solution in lower volumes (1.0, 0.5, and 0.2 μl) yielded an “above range” osmolarity reading. Because osmolarities exceeding 400 mOsm/L were reported as “above range” and were arbitrarily recorded as 400 mOsm/L, the actual measured values were likely higher. Conversely, after the application of a 271.25 mOsm/L test solution, which was less than the TearLab osmometer measurement range, ‘below range’ was displayed as expected with higher volumes (2.0 and 5.0 μl), but inaccurately high measured values (289.7–307.3 mOsm/L were displayed for volumes < 1.0 μl).

In an experiment to assess the difference of the measured osmolarity between different standard solution concentrations, the ‘High’ and ‘Normal’ osmolarity standards provided by TearLab were measured (Supplementary Fig. 1). The osmolarity of the standard solutions provided by TearLab as measured using the TearLab system revealed that as the volume applied to both solutions decreased, the measured osmolarity was higher than the actual osmolarity of both standard solutions. Especially, when small sample volumes (0.2 and 0.5 μl) were applied, the osmolarity was significantly higher than that of higher sample volumes (1.0 and 2.0 μl) (p < 0.001, 0.035, 0.019, and 0.021, respectively). The difference between measured osmolarity and actual osmolarity was > 20 mOsm/L in measurement of 0.2 μl of high and normal standard solutions.

Inter-assay and intra-assay variability results are shown in Tables 7 and 8. The inter-assay variabilities of the 300 and 347.5 mOsm/L solutions with applied volumes of 2.0 and 0.2 μl were calculated. When 2.0 μl was applied, the osmolarity measurements of both standard solutions were generally similar to the original osmolarity value. However, when 0.2 μl of the same osmolarity solutions was applied, the measured osmolarity was higher than the original osmolarity value and was particularly ‘above range’ (> 400 mOsm/L), in the 347.5 mOsm/L test solution (Table 7). Intra-assay variability of the 300 and 347.5 mOsm/L solutions with applied volumes of 0.2 and 2.0 μl showed increased variability of osmolarity by 0.2 μl sample volume (Table 8). The coefficients of variation (CoV) for inter-assay variability of the 300 and 347.5 mOsm/L test solutions were 3.98 (0.2 μl) and 3.01 (2.0 μl) in 300 mOsm/L, and 2.26 (0.2 μl) and 1.91 (2.0 μl) in 347.5 mOsm/L. The CoV of intra-assay variability of 300 and 347.5 mOsm/L test solutions were 4.02 (0.2 μl) and 0.65 (2.0 μl) in the 300 mOsm/L standard solution and 2.18 (0.2 μl) and 0.25 (2.0 μl) in the 347.5 mOsm/L standard solution. Both in vitro analysis of intra-assay and inter-assay variability confirms that the smaller the applied volume, the higher the variability of measurement results.

Discussion

In this study, we focused on tear meniscus osmolarity measurement by the TearLab osmolarity system in the lower temporal TMH of SS ADDE, non-SS ADDE, and CCh subgroups. Since tear meniscus osmolarity is influenced by tear volume, which is determined by the balance between tear secretion, evaporation, and drainage, we anticipated significant differences in osmolarity between these three groups and the other two groups. Especially, because tear secretion is most significantly decreased in SS ADDE, tear osmolarity was expected to be the highest in this group. These predictions were consistent with the results of OSMdirect, which concurred with prior reports of higher osmolarity in DE patients than in normal patients21,28,31,32.

Compared to the in situ method, the OSMpipette demonstrated different results. Tear meniscus osmolarity measured by the ex situ method using a micropipette did not produce significantly different measurement variation between all groups. Moreover, in Table 5, statistically significant but weak negative correlations were observed between OSMdiff and both the Schirmer test and TMH, suggesting a mild sample volume dependency of osmolarity measurement. The smaller the tear sample volume applied to the test card, the higher the tear osmolarity measurement variability, especially in ADDE with markedly low TMH. These results may be attributed to the volume-dependent evaporation effect. Collecting 1.0 µL from dry eye patients is likely pulling in both tear fluid and interstitial fluid, which may not be in equilibrium with the precorneal tear film. As a result, the pipetting technique could potentially underestimate the meniscus osmolarity. Additionally, since we used a 0.5 mL aliquot, the evaporative effects were less pronounced.

The CCh group also exhibited significantly greater differences between OSMpipette and OSMdirect relative to the NC and EDE groups, as did the ADDE subgroups. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the different distributions of tear film in NC, CCh, and ADDE. CCh, defined as the lax of redundant conjunctiva, causes ocular symptoms due to tear film instability and disruption of tear distribution34,35. Though tear hyperosmolarity has not been fully evaluated in CCh, Fodor et al. reported tear hyperosmolarity in patients with severe CCh, indicating the pooling of ‘toxic tears’ containing high concentration of inflammatory cytokines in the lower fornix and inflammation of the ocular surface36, and Gumus et al. found high tear osmolarity in CCh associated with reduced conjunctival epithelial thickness37. We speculate that the discrepancy of measured osmolarity between OSMpipette and OSMdirect in CCh, which was similar to ADDE, was caused by low temporal TMH secondary to temporal chalatic conjunctiva. The redundant folds of conjunctiva, primarily located on the temporal and nasal areas, result in very low tear lakes in the temporal and nasal portions, while the center area of the conjunctiva maintains a relatively intact or high tear lake38,39. Consequently, in CCh, in which temporal tear volume is relatively low due to disrupted tear film, tear hyperosmolarity is inevitable, as in ADDE. Therefore, altered tear distribution and disruption of the temporal tear meniscus are likely the causative factors for tear hyperosmolarity in CCh. In CCh patients, careful inspection of temporal conjunctival folds during slit-lamp examination is crucial for reliable tear osmolarity measurement.

Laboratory findings were consistent with clinical findings. We also identified significant sample volume dependency in TearLab osmometer measurements of test solutions. Higher osmolarity value in each sample was consistently observed at volumes < 0.5–1.0 µl. In vitro experiments were designed to simulate the meniscus of human tears, but tear distribution is determined by complex surface properties of the eye and could not be completely replicated with the artificial tear meniscus used in our studies. Further, samples applied by micropipette would be larger than the volume of tears that can be absorbed from the human tear meniscus by the test card. Therefore, the difference in tear osmolarity between the two methods could potentially have been underestimated. The concentration at the air-fluid interface, which was the osmolarity intended to be measured by the OSMdirect, might differ from that of a 1.0 µL sample by the OSMpipette. The latter might include tears with lower concentrations originating from deeper layers and/or radially from the stroma as fluid was drawn out. These extracted tears were not in equilibrium with the precorneal tear film and were likely closer to the osmolarity of interstitial body fluid. Additionally, once the sample was collected in the microtube, a non-linear osmolarity gradient might develop over time, depending on the duration it remains in the microtube. Upon expulsion, the sample was further subjected to volume-dependent evaporation effects, which were challenging to quantify or control.

The overall CoV value of inter- and intra-assay variability of the TearLab osmometer ranged from 0.25 to 4.02% in in vitro analysis in our study. Specifically, the CoV demonstrated slightly higher variability in osmolarity measurements for the 0.2 µL sample volume (4.02%) compared to the 2.0 µL sample volume (0.65%) when using the 300 mOsm/L standard solution. This variability is notably greater than the CoV reported in two clinical studies: 2.5% reported by Fortes et al.40 and 2.9% reported by Eperjesi et al.31 The TearLab manufacturer also presented a CoV < 1.5% in clinical assessment of the TearLab osmometer. Under clinical conditions, patient tear volume and TMH are expected to exhibit significant variability due to individual differences and disease states. Consequently, the CoV for the TearLab osmometer in clinical practice would likely be higher than that observed in controlled in vitro evaluations. However, our in vitro results contradicted this expectation, which may be attributed to the volume-dependent evaporation effect, significantly impacting osmolarity measurements at smaller sample volumes, as well as potential pipetting errors during sample handling. The low volume of tears would evaporate more quickly and in a highly time-dependent manner, leading to larger values and greater standard deviations.

Our study had several limitations that should be considered in its interpretation. Collecting tear samples presented procedural challenges, especially in ADDE. For accurate sampling, tears were carefully collected by a single skilled examiner to avoid irritation and prevent reflex tearing. In addition, although the artificial tear meniscus system was designed to mimic the human tear meniscus as closely as possible, an artificial tear meniscus could have caused a minor discrepancy in the application method of tear samples and standard osmolarity test solutions. Small amount of evaporation during collecting tear samples with micropipette and constructing artificial tear meniscus could have been unavoidable. To minimize this evaporation effect, all the procedures were done in the shortest time possible in succession by one examiner with interval times less than 10 s. Also, as the Schirmer I test is a relatively invasive procedure compared to other dry eye tests, the results of following tests may have been affected. Therefore, the filter paper strip was placed into the patient’s lower fornix as carefully as possible not to damage the ocular tissues by one skilled examiner, and after 30 min, tBUT and OSS were examined. All ocular surface parameter examinations were conducted in one consecutive session, in a way that minimally affect the latter measurements because the order of dry eye tests conducted highly impacts the outcomes, and in a similar time at the afternoon considering diurnal variations in TMH and tBUT41,42. Furthermore, though our normal group had OSDI scores greater than 13, which could suggest the presence of DED, we did not classify them as having DED. This decision was consistent with prior research, indicating that OSDI alone is insufficient to diagnose clinically evident DED. Both symptoms and objective signs must be considered, and an OSDI score ≥ 33 is typically used to define severe DED43,44. Additionally, we measured only one eye in each patient, which may have led to an underestimation of the direct osmolarity, as the FDA label recommends taking the maximum osmolarity from both eyes. If this guideline had been followed, the direct osmolarities of the non-normal groups would likely have been significantly higher compared to the normal cohort. Moreover, there were significant differences in the ratios of gender composition, age, laterality of groups, and the use of dry eye treatment such as eyedrops or wipes was not investigated despite their potential influence on the result of our study. While the measurement of direct osmolarity was made in the temporal area, the TMH was measured in the central area of the tear meniscus. This would have affected the results, however, as the central TMH is more commonly analyzed in clinical practice, our results also give clinical significance to dry eye specialists. In our in vitro study, to avoid the potential of measurement error due to the differences in the characteristics of solutions, we prepared our test solutions by using only reference solutions provided by TearLab. We did not validate the osmolarities of the test solution mixtures used in our study, and their values might vary without additional verification. Furthermore, the TearLab control solutions were calibrated to simulate tear osmolarity readings. For example, the high control was labeled to read approximately 338 mOsm/L, even though it contained 330 mOsm/L NaCl. This discrepancy arises due to an impedance offset between NaCl and human tear fluid. The TearLab was specifically designed to report osmolarity as it would occur in human tears, not as a direct NaCl equivalent.

In conclusion, this study prospectively and experimentally investigated the effects of temporal TMH on tear osmolarity measurements, and both in vitro and clinical analyses revealed a tendency to report higher tear osmolarity in inverse proportion to the volume of tear sample applied to the TearLab osmometer. Based on these results, tear osmolarity measurements should be interpreted cautiously in patients with low tear volume or altered tear distribution, especially ADDE and CCh.

Methods

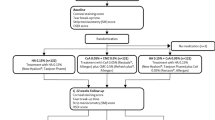

This study prospectively analyzed tear meniscus osmolarity by the TearLab system and identified contributing factors to measurement inconsistencies. Schematic flow chart of study protocol is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. The clinical part of the study was approved by the Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB no. DSMC 2021-04-019) and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after a detailed explanation of the study. This single-institution prospective case–control study was conducted from June 1, 2021, until October 31, 2021.

Subjects

One hundred and eighty-two subjects were enrolled in the study. The study investigator (J.L.) collected clinical and tear meniscus osmolarity data from the randomly selected unilateral eye of enrolled participants; 101 right eyes and 81 left eyes. Participants were divided into DE, CCh, and NC groups according to the following criteria: TMH ≤ 200 μm, Schirmer’s test ≤ 10 mm/5 min, and tBUT ≤ 7 s45. Subjects who did not meet any of these criteria and had normal conjunctival folds were allocated as NC. Subjects with a tBUT ≤ 7 s, but TMH > 200 μm, Schirmer’s test > 10 mm/5 min, and no conjunctival folds were categorized into the EDE group. Subjects meeting all three criteria—TMH ≤ 200 μm, Schirmer’s test ≤ 10 mm/5 min, and tBUT ≤ 7 s—and having normal conjunctival folds were classified as ADDE. The ADDE group was further divided into two subgroups based on the presence of anti-Ro antibodies: SS ADDE and non-SS ADDE. Patients with prominent conjunctival folds on slit-lamp microscopy were allocated as CCh. Criteria are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) lacrimal drainage disorders such as punctal stenosis, canalicular anomalies, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, or temporary punctal occlusion within 3 months, or patent permanent punctal occlusion or within 6 months; (2) history of ocular surgery within the previous 6 months or ocular trauma in the previous 3 months; (3) use of antiglaucoma eyedrops; and (4) use of contact lenses within the previous 72 h.

In vivo measurements

Assessment of ocular surface parameters was conducted in the following order: modified OSDI questionnaire (Korean version based on the Korean dry eye guidelines)46, TMH by optical coherence tomography (OCT), tear osmolarity using the TearLab osmolarity system (Escondido, CA, USA), Schirmer I test, tear matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) point-of-care test using InflammaDry® (Quidel, San Diego, CA, USA), tBUT, and OSS according to the Oxford scheme1,3. Prior to undergoing ophthalmologic tests, participants were asked to answer the OSDI questionnaire, which includes 12 questions related to visual disturbance (sensitivity to light, gritty discomfort, sore eyes, blurred vision, or poor vision), eye discomfort in certain environments (windy conditions, low humidity, or air-conditioned areas), and visual function (problems reading, driving at night, working on a computer, or watching TV). The Schirmer I test was used to assess tear production and was performed by placing a standard filter paper strip Schirmer tear® (EagleVision Inc., Memphis, TN, USA) over the lateral fornix of the unanesthetized eye for 5 min and measuring the zone of moisture from tears. tBUT and OSS were determined by using a small amount of fluorescein dye to avoid excessive fluorescein instillation and reflex tear expression with a wetted fluorescein strip (Fluorescein paper strips, Haag-Streit AG, Switzerland), observed by yellow-filtered slit-lamp microscope by a single examiner (J.H.J.).

TMH value was measured by following method using a swept-source OCT device (DRI OCT Triton; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) operated by a single experienced technician47. Briefly, a vertical raster image of the eye was obtained after voluntary blinking in a dark room. TMH was defined as the distance between the cornea-meniscus junction and the lower eyelid-meniscus junction.

A TearLab™ osmolarity system (model #200001REV E, serial number 012003011158) and osmolarity control solutions (normal and high) were purchased from TearLab Corporation. Osmolarity reference standard solutions (CON-TROL 100, 290, and 500 mOsm/L) were purchased from Precision Systems Inc. (Natick, MA, USA). Standard solutions of each osmolarity were prepared by combining osmolarity reference standard solutions of 100, 290, and 500 mOsm/L without dilution. Manual micropipettes and disposable tips were purchased from INTEGRA Biosciences Corp. (EVOLVE manual pipette and GripTip pipette tips. Zizers, Switzerland).

Tear meniscus osmolarity was measured using a TearLab™ osmolarity system in the same room (25 ± 3 °C, relative humidity of 40 ± 5%). The instrument was checked regularly prior to use following the manufacturer’s guidelines. All tear meniscus osmolarity measurements were performed by a single experienced examiner (J.L.). Measurements were performed with the patient in the seated position in an ophthalmology chair next to a slit lamp biomicroscope. Tear meniscus osmolarity was measured by two different methods. First, under a slit lamp biomicroscope, 1.0 µl of tears was carefully collected using a micropipette to prevent reflex tear secretion from the tear meniscus, and subsequently applied to a TearLab test card, forming an artificial tear meniscus by dripping test solutions into the rectangular space created by the cap ceiling and internal cylindrical structure of the microtube (OSMpipette). Subsequently, the TearLab osmometer test card was applied to the artificial tear meniscus until a beep sound was heard. For the second measurement, 30 min after the first measurement, the patient was slightly tilted posteriorly in the ophthalmology chair according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, and the TearLab™ osmometer test card was placed in contact with the tear meniscus collected in the temporal meniscus until a beep sound was heard (OSMdirect). The interval time of 30 min was chosen considering the tear turnover rate, minimizing physiological change and avoiding reflex tearing48. All ophthalmic examinations were performed in the afternoon (from 2 to 4 PM) to minimize diurnal variations in tear meniscus osmolality.

In vitro measurements

To minimize variation caused by differences in room temperature or humidity that could affect test solution evaporation and consequently osmolarity, all studies were performed simultaneously in single experiment, except for inter-assay variability experiments. All analyses were conducted in a single room at 25 ± 3 °C and relative humidity 40 ± 5%. To identify the effects of sample volume on osmolarity measurement, each of the four different osmolarity test solutions (271.25, 300, 347.5, and 395 mOsm/L) were prepared by combining reference standard solutions. Each osmolarity measurement was obtained by subsampling five different volumes (0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 5.0 μL) from a 0.5 mL aliquot. The aliquot was transferred into PCR tubes (BRAND® PCR tubes, BR781313, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and securely sealed with paraffin sealing film. To minimize evaporation-related errors, the PCR tubes were filled as completely as possible, reducing the risk of fluid loss compared to partially filling a 1.5–2.0 mL microtube. To closely replicate the human tear meniscus, the connecting part of a new microtube cap was cut off, inverted, and used as a platform where the test solutions were applied to the angled inner wall to form an artificial tear meniscus. The osmolarity measurements were then obtained by bringing the tip of the test card into contact with the sample. Each measurement was repeated three times. To eliminate device-to-device error that could occur between TearLab osmolarity test pens, only a single pen was used for measurement among the two pens provided by the TearLab osmometer system (Supplementary Fig. 4).

TearLab provides two osmolarity standards: high (337 ± 15 mOsm/L) and normal (297 ± 15 mOsm/L). To assess the difference of osmolarity measurements between different standard solution concentrations, the osmolarity of each control solution was measured using TearLab test cards at volumes of 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 μl. The two control solutions were applied for each of four different volumes to measure osmolarity, and each osmolarity and volume was measured three times.

Inter-assay variability: Osmolarity test solutions of 300 and 347.5 mOsm/L were prepared in 0.5 mL aliquots. Subsamples of 0.2 μL or 2.0 μL were then applied to the test card for measurement. The osmolarity measurements were conducted twice daily, at a 9-h interval (9 AM and 6 PM), in the same room (25 ± 3 °C, relative humidity 40 ± 5%) over a period of 5 consecutive days. If the measured value exceeded the measurement range of the TearLab and was displayed as “over range,” it was arbitrarily recorded as 400 mOsm/L for statistical analysis.

Intra-assay variability: Volumes of 0.2 or 2.0 μl of 300 or 347.5 mOsm/L test solutions were measured five successive times on the test card.

Data handling and statistics

The sample size was calculated by the G*Power 3.1.9.2 (Franz Faul, University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany). A total sample size of 160 participants was needed to account for 80% power, a statistical significance level of 0.1, and an effect size of 0.25 to detect differences in tear meniscus osmolarity among five independent groups. The normality test of the quantitative variables of each group was performed through the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and normality was satisfied in all variables (p > 0.05). Statistical data were collected from individual experiments. The difference of various ocular surface parameters and mean osmolarity differences between direct and micropipette measurements (OSMdiff) within the NC, DE subgroups, and CCh groups were measured. Data were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD posthoc comparison to determine statistical significance. A paired T-test was performed for analysis of OSMdiff. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to detect statistically significant relationships between various ocular surface parameters, and differences between OSMdirect and OSMpipette. Correlation analysis was repeated with or without the CCh group, as the central TMH of CCh patients is unlikely to reflect the temporal TMH value. Therefore, the correlations between Schirmer’s test results and OSMdiff were also analyzed. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Lemp, M. A. & Foulks, G. N. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: Report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul. Surf. 5, 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70081-2 (2007).

Lemp, M. A. Report of the National Eye Institute/Industry workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes. CLAO J. 21, 221–232 (1995).

Bron, A. J. et al. Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: Report of the Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop. Ocul. Surf. 5, 108–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70083-6 (2007).

Willcox, M. D. P. et al. TFOS DEWS II tear film report. Ocul. Surf. 15, 366–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.03.006 (2017).

Tomlinson, A. & Khanal, S. Assessment of tear film dynamics: Quantification approach. Ocul. Surf. 3, 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70157-x (2005).

Baudouin, C. et al. Role of hyperosmolarity in the pathogenesis and management of dry eye disease: Proceedings of the OCEAN group meeting. Ocul. Surf. 11, 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2013.07.003 (2013).

Gaffney, E. A., Tiffany, J. M., Yokoi, N. & Bron, A. J. A mass and solute balance model for tear volume and osmolarity in the normal and the dry eye. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 29, 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.11.002 (2010).

McMonnies, C. W. An examination of the relationship between ocular surface tear osmolarity compartments and epitheliopathy. Ocul. Surf. 13, 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2014.07.002 (2015).

Messmer, E. M., Bulgen, M. & Kampik, A. Hyperosmolarity of the tear film in dry eye syndrome. Dev. Ophthalmol. 45, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1159/000315026 (2010).

Braun, R. J., King-Smith, P. E., Begley, C. G., Li, L. & Gewecke, N. R. Dynamics and function of the tear film in relation to the blink cycle. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 45, 132–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2014.11.001 (2015).

King-Smith, P. E., Ramamoorthy, P., Braun, R. J. & Nichols, J. J. Tear film images and breakup analyzed using fluorescent quenching. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 6003–6011. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12628 (2013).

Gilbard, J. P. et al. Morphologic effect of hyperosmolarity on rabbit corneal epithelium. Ophthalmology 91, 1205–1212. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34163-x (1984).

Luo, L., Li, D. Q., Corrales, R. M. & Pflugfelder, S. C. Hyperosmolar saline is a proinflammatory stress on the mouse ocular surface. Eye Contact Lens 31, 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.icl.0000162759.79740.46 (2005).

Gilbard, J. P., Rossi, S. R., Gray, K. L., Hanninen, L. A. & Kenyon, K. R. Tear film osmolarity and ocular surface disease in two rabbit models for keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 29, 374–378 (1988).

Liu, H. et al. A link between tear instability and hyperosmolarity in dry eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50, 3671–3679. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.08-2689 (2009).

Julio, G., Lluch, S., Pujol, P. & Merindano, M. D. Effects of tear hyperosmolarity on conjunctival cells in mild to moderate dry eye. Ophthal. Physiol. Opt. 32, 317–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.2012.00915.x (2012).

Li, D. Q. et al. JNK and ERK MAP kinases mediate induction of IL-1beta, TNF-alpha and IL-8 following hyperosmolar stress in human limbal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 82, 588–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2005.08.019 (2006).

Solomon, A. et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory forms of interleukin-1 in the tear fluid and conjunctiva of patients with dry-eye disease. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 2283–2292 (2001).

Luo, L., Li, D. Q. & Pflugfelder, S. C. Hyperosmolarity-induced apoptosis in human corneal epithelial cells is mediated by cytochrome c and MAPK pathways. Cornea 26, 452–460. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e318030d259 (2007).

Versura, P., Profazio, V. & Campos, E. C. Performance of tear osmolarity compared to previous diagnostic tests for dry eye diseases. Curr. Eye Res. 35, 553–564. https://doi.org/10.3109/02713683.2010.484557 (2010).

Lemp, M. A. et al. Tear osmolarity in the diagnosis and management of dry eye disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 151, 792–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.032 (2011).

Tomlinson, A., McCann, L. C. & Pearce, E. I. Comparison of human tear film osmolarity measured by electrical impedance and freezing point depression techniques. Cornea 29, 1036–1041. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181cd9a1d (2010).

Pena-Verdeal, H., Garcia-Resua, C., Minones, M., Giraldez, M. J. & Yebra-Pimentel, E. Accuracy of a freezing point depression technique osmometer. Optom. Vis. Sci. 92, e273-283. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0000000000000669 (2015).

Gokhale, M., Stahl, U. & Jalbert, I. In situ osmometry: Validation and effect of sample collection technique. Optom. Vis. Sci. 90, 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0b013e31828aaf10 (2013).

Small, D., Hevy, J. & Tang-Liu, D. Comparison of tear sampling techniques for pharmacokinetics analysis: Ofloxacin concentrations in rabbit tears after sampling with schirmer tear strips, capillary tubes, or surgical sponges. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 16, 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2000.16.439 (2000).

García, N. et al. Lack of agreement among electrical impedance and freezing-point osmometers. Optom. Vis. Sci. 93, 482–487. https://doi.org/10.1097/opx.0000000000000817 (2016).

Szalai, E., Berta, A., Szekanecz, Z., Szucs, G. & Modis, L. Jr. Evaluation of tear osmolarity in non-Sjogren and Sjogren syndrome dry eye patients with the TearLab system. Cornea 31, 867–871. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182532047 (2012).

Sullivan, B. D. et al. Clinical utility of objective tests for dry eye disease: variability over time and implications for clinical trials and disease management. Cornea 31, 1000–1008. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e318242fd60 (2012).

Tashbayev, B. et al. Utility of tear osmolarity measurement in diagnosis of dry eye disease. Sci. Rep. 10, 5542. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62583-x (2020).

Szczesna-Iskander, D. H. Measurement variability of the TearLab Osmolarity system. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 39, 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2016.06.006 (2016).

Eperjesi, F., Aujla, M. & Bartlett, H. Reproducibility and repeatability of the OcuSense TearLab osmometer. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 250, 1201–1205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-012-1961-4 (2012).

Bunya, V. Y. et al. Variability of tear osmolarity in patients with dry eye. JAMA Ophthalmol. 133, 662–667. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0429 (2015).

Yoon, D., Gadaria-Rathod, N., Oh, C. & Asbell, P. A. Precision and accuracy of TearLab osmometer in measuring osmolarity of salt solutions. Curr. Eye Res. 39, 1247–1250. https://doi.org/10.3109/02713683.2014.906623 (2014).

Huang, Y., Sheha, H. & Tseng, S. C. Conjunctivochalasis interferes with tear flow from fornix to tear meniscus. Ophthalmology 120, 1681–1687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.007 (2013).

Chan, D. G., Francis, I. C., Filipic, M., Coroneo, M. T. & Yong, J. Clinicopathologic study of conjunctivochalasis. Cornea 24, 634; author reply 634–635, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ico.0000157653.91093.30 (2005).

Fodor, E., Kosina-Hagyo, K., Bausz, M. & Nemeth, J. Increased tear osmolarity in patients with severe cases of conjunctivochalasis. Curr. Eye Res. 37, 80–84. https://doi.org/10.3109/02713683.2011.623810 (2012).

Gumus, K. & Pflugfelder, S. C. Conjunctivochalasis and tear osmolarity are associated with reduced conjunctival epithelial thickness in dry eye. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 227, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2021.02.009 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. The impact of nasal conjunctivochalasis on tear functions and ocular surface findings. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 144, 930–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.037 (2007).

Chhadva, P. et al. The impact of conjunctivochalasis on dry eye symptoms and signs. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56, 2867–2871. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.14-16337 (2015).

Fortes, M. B. et al. Tear fluid osmolarity as a potential marker of hydration status. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43, 1590–1597. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31820e7cb6 (2011).

Li, M. et al. Daytime variations of tear osmolarity and tear meniscus volume. Eye Contact Lens 38, 282–287. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICL.0b013e31825fed57 (2012).

Bitton, E., Keech, A., Jones, L. & Simpson, T. Subjective and objective variation of the tear film pre- and post-sleep. Optom. Vis. Sci. 85, 740–749. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0b013e318181a92f (2008).

Yazdani, M. et al. Evaluation of the ocular surface disease index questionnaire as a discriminative test for clinical findings in dry eye disease patients. Curr. Eye Res. 44, 941–947. https://doi.org/10.1080/02713683.2019.1604972 (2019).

Baudouin, C. et al. Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: A clear and practical algorithm. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 98, 1168–1176. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304619 (2014).

Wolffsohn, J. S. et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul. Surf. 15, 539–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001 (2017).

Eom, Y., Hyon, J. Y., Lee, H. K., Song, J. S. & Kim, H. M. A multicenter cross-sectional survey of dry eye clinical characteristics and practice patterns in Korea: The DECS-K study. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 65, 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10384-020-00803-7 (2021).

Jun, J. H., Lee, Y. H., Son, M. J. & Kim, H. Importance of tear volume for positivity of tear matrix metalloproteinase-9 immunoassay. PLoS One 15, e0235408. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235408 (2020).

Tavakoli, A., Markoulli, M., Flanagan, J. & Papas, E. The validity of point of care tear film osmometers in the diagnosis of dry eye. Ophthal. Physiol. Opt. 42, 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12901 (2022).

Funding

This research was supported by the Bisa Research Grant of Keimyung University in 20240213. This funding body had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J Lee and JH Jun: conceived and designed the experiments; J Lee and JG Kim: collected the data; J Lee, SP Bang, and JH Jun: analyzed the data and wrote the paper; SP Bang and JH Jun: approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement of ethics

The clinical part of the study was approved by the Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB No. DSMC 2021-04-019), and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after a detailed explanation of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Bang, S.P., Kim, JG. et al. Impact of temporal tear meniscus height on the tear osmolarity measurements. Sci Rep 15, 27459 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93764-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93764-1