Abstract

With the rapid development of low-carbon buildings and energy-saving technologies, phase change materials (PCM) have been extensively applied in building floor heating systems due to their excellent thermal energy storage and temperature control characteristics. However, traditional encased PCM radiant floor heating systems (RFHS) exhibit drawbacks including slow thermal response, low thermal efficiency, and excessive structural layer thickness. This study proposes an innovative solution through CFD numerical simulation: replacing the conventional circular encasement with an elliptical encasement and optimizing the elliptical axis ratio to enhance the system’s thermal performance and reduce mortar layer thickness, thereby lowering construction costs. The study analyzes the thermal state of PCMs, temperature variations of the floor structure, and heat flux distribution. The results show that as the short axis (a) length of the elliptical encasement decreases, the floor’s thermal response becomes faster. When a = 1.5 times the radius of the hot water pipe, the floor achieves the optimal balance between thermal comfort and energy efficiency. Compared to the traditional design, this approach not only enhances thermal response speed and reduces energy consumption but also decreases the mortar layer thickness by 16.7%. This study provides a theoretical basis for optimizing RFHS integrated with PCMs and holds significant potential for engineering applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of heightened attention to low-carbon buildings and passive energy-saving technologies, phase change materials (PCMs) are favored in the construction industry for their excellent thermal storage capacity and temperature regulation properties1,2. The use of PCMs in flooring materials aims to achieve higher energy efficiency and improve indoor thermal comfort3. To improve the performance of composite PCM radiant floor heating systems, current research mainly focuses on three aspects: the preparation of new PCMs, the development of operational strategies, and the configuration of floor structure layers.

The preparation of new PCMs typically involves mixing high thermal conductivity substances such as inorganics4,5, organic compounds6,7 and nanomaterials8,9, as well as structure-stabilizing agents with PCM to improve the thermal conductivity and stability of the new PCM. Additionally, the incorporation of PCM microcapsules into concrete and mortar is an effective approach to enhance the overall heat storage performance of floor structural materials10,11.

The optimization methods for the operational strategy of radiant floor heating systems include: designing dynamic operation schedules based on peak-valley electricity pricing policies to reduce operating costs12,13; implementing intelligent control of the floor system based on outdoor temperature and weather forecasts to reduce unnecessary energy consumption14; and coupling renewable energy sources, such as solar collectors, with PCM energy storage systems to reduce carbon emissions and improve energy efficiency15.

In terms of floor structure layer configuration, improvements in the thermal performance of the heating system are usually achieved by varying the combination of the PCM layer with heat source pipes or heating mats. Common configurations of RFHS integrated with PCM typically include layered, embedded, and encased types.

The layered type of RFHS integrated with PCM refers to a configuration where the PCM layer is stacked above or below the heat source pipes or heating mats. Zhou et al.16 found that floor structures utilizing PCM as a thermal storage material release heat for approximately twice as long as those using sand. Cheng et al.17 discovered that optimizing the thermal conductivity of PCM within a specific range could significantly enhance the energy efficiency of heating systems and minimize the reliance on insulation materials. Huang et al.18 found that the placement of PCM between two capillary mats has been found to effectively meet the demand for long-term intermittent heating. Building on this model, Feng et al.19’s numerical simulation study indicated that errors in PCM’s DSC measurements significantly affect the simulation results of the RFHS. Maria et al.20 through TRNSYS simulations found that composite PCM heating systems save up to 40% of the thermal load compared to traditional heating systems. It was subsequently discovered that the optimal placement of the PCM layer is below the hot water pipes21, a conclusion also reached by Barbara et al.22. Chen et al.23 found that composite PCM floor heating can regulate room heating and cooling rates, offering greater energy savings and enhanced comfort. Additionally, Jin et al.24 incorporated a two-layer PCM system into the floor heating system, strategically positioning two layers of PCM with distinct phase change temperatures above the water pipe to effectively regulate room temperature during both summer and winter seasons. Sun et al.25, using an electric heating panel as the heat source face, studied the effects of the vertical arrangement of dual-layer phase change materials on cooling and heating performance.

The embedded type of RFHS integrated with PCM, based on the layered approach, aims to increase the heated surface area of the PCM by semi-embedding or fully embedding the heat source pipes within the PCM layer. Zhao et al.26 investigated the combination form and observed that by enhancing the thermal conductivity of PCM, it is possible to reduce thermal inertia and enhance heat transfer efficiency, thereby effectively shortening the time of heat storage. González et al.27 examined how the positional relationship between the hot water pipes and PCM affects the thermal performance of the floor heating system, finding that the melting rate of PCM is significantly influenced by the temperature of the hot water pipes, while the solidification rate is more affected by indoor temperature and the floor thickness. Jiang et al.28 found that semi-embedded PCM floor heating systems have higher energy efficiency. Xia et al.29, in their experimental study, examined how the vertical positioning of PCM layers within a capillary-embedded dual-layer PCM floor affects its thermal performance and found that placing the heating layer above and the cooling layer below offers optimal results. Building on this, Xu et al.30 studied the thermal efficiency of this system under winter and summer conditions. Subsequently, Sun et al.31 further explored and proposed optimal distances, diameters, and positions for capillaries within this model. Sui et al.32 discovered through TRNSYS numerical simulations that the thermal property of floor heating system is greatly affected by the phase transition temperature, latent heat and thickness of PCM. Yu et al.33, based on a capillary-embedded PCM setup, stacked double layers of PCM with distinct phase change temperatures and found this arrangement could eliminate floor overheating, reduce temperature fluctuations, and enhance energy efficiency.

The encased type involves the addition of an encasement to the exterior of the hot water pipe, while simultaneously filling the gap with PCM. This configuration allows for extensive contact between the PCM and the hot water pipes, making the heating process more efficient. Lu et al.34 were the first to propose the concept of an encased system in their model coupling solar thermal water systems with PCM flooring, and through numerical simulation studies, they found that this setup can reduce energy consumption by 5.87% compared to the case without PCM. In their experimental study35, a zoned operation strategy was employed to meet the indoor comfort requirements. Later, through numerical simulations, they discovered that reducing pipe spacing and solidification temperature, increasing the thickness of the PCM layer, and expanding the solar heat collection area could enhance indoor temperature36. Liu et al.37 discovered that the temperature fluctuation of 12.3 K can be reduced under the condition of constant PCM volume, by appropriately increasing the diameter ratio of the casing to the hot water pipe. In our previous study38, we found that the eccentric position of the hot water pipe in the PCM encasement is related to the thermal performance of the floor system. When the water pipe is offset in upward and horizontal directions, the greater the moving distance, the better the thermal performance of the floor.

Existing literature indicates that the encased PCM, due to its unique structural characteristics, fully surrounds the hot water pipes, offering a larger heat transfer area compared to layered and embedded structures39. However, this design presents several notable drawbacks. Firstly, the complete enclosure of the hot water pipes by PCM restricts the rapid transfer of heat to the floor, resulting in significant thermal lag. Additionally, the PCM at the bottom of the hot water pipe often fails to completely melt, which reduces the phase change rate and subsequently impacts the system’s thermal performance. Lastly, the encased structure requires additional mortar coverage during floor construction, leading to increased construction costs. Therefore, this paper presents an innovative approach by modifying the shape of the PCM encasement from its original round barrel design to an oval barrel configuration. This modification aims to enhance heat penetration efficiency through the PCM layer, thereby addressing the current issues of slow floor temperature response and low thermal efficiency during the heating stage, and the objective of cost reduction in construction can be achieved by simultaneously reducing the thickness of the floor structure layer. This study uses CFD numerical simulation to analyze the melting and solidification states of PCM, examine the temperature evolution of the floor structure, and investigate the temperature distribution and heat flux on the floor surface, in order to reveal the thermal performance of the improved encased radiant floor heating system.

Method

Physical model description

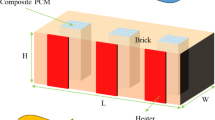

Figure 1 displays the structure of a typical encased type radiant heating floor37, which is created by authors through Adobe Photoshop 2025 (https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html). The floor structure layer consists of the decoration layer, mortar layer, and insulation layer with thicknesses of 20 mm, 90 mm, and 30 mm respectively. The hot water pipes are embedded and arranged parallel at the bottom of the mortar layer, with a pipe radius of 15 mm and a center-to-center spacing of 150 mm. An encasement with a radius of 30 mm is concentrically and parallelly arranged with the hot water pipes, and PCM is filled in the space between the encasement and the hot water pipe. A representative section from the diagram is selected as the physical model basis for this study, and a two-dimensional heat transfer model is established for it. The physical properties of floor structural layers and PCM are listed in (Table 1).

The structural diagram of the conventional encased PCM radiant floor heating system. This figure illustrates the structural design of the conventional encased PCM radiant floor heating system, highlighting its key components and layout. The image was created using Adobe Photoshop 2025 (https://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop.html).

To address the issues of thermal lag and excessive thickness of the mortar layer in traditional concentric encased PCM radiant floor heating systems, this study changes the cross-sectional shape of the encasement from circular to elliptical with the same area. This modification reduces the thickness of the PCM above the water pipe, enhances the efficiency of heat transfer to the floor, and compresses the thickness of the floor structure. As shown in (Fig. 2), the elliptical encasement is defined with a short semi-axis a (in the vertical direction) and a long semi-axis b (in the horizontal direction), while the radius of the hot water pipe is denoted as r.

The original concentric arrangement is designated as Case-1. Subsequent cases involve progressively shortening the length of the elliptical encasement’s short semi-axis until it is tangent to the hot water pipe, resulting in four distinct cases: Case-2 (a = 1.75r), Case-3 (a = 1.5r), Case-4 (a = 1.25r), and Case-5 (a = r). Due to the compression of the encasement diameter in the vertical direction, the thickness of each subsequent floor structure layer is reduced by 7.5 mm, and the amount of mortar filling is also decreased. While maintaining a constant distance from the top of the encasement to the floor surface (50 mm), the usage of mortar is reduced by 10.5% for Case-2, 21.1% for Case-3, 31.6% for Case-4, and 42.2% for Case-5 compared to Case-1. In addition, according to the peak and valley electric charges policy in most areas of China (0:00–8:00 is the electricity consumption trough stage, 8:00–24:00 is the electricity peak stage), the corresponding heat storage period and heat release period are set.

Numerical model description

This study employs the commercial CFD simulation software ANSYS Fluent R1 to establish a two-dimensional heat transfer model and conduct numerical simulations38. The given equation represents the physical phenomena within a numerical model that simulates the process of heat transfer39:

The symbols ρ and λ represent the density and thermal conductivity of the floor material, respectively. The symbol H denotes enthalpy, which is defined as follows39:

For flooring materials:

For PCM:

The specific heat capacities of PCM and floor materials are denoted as CP, PCM and CP respectively, while LPCM represents the latent heat. TS and TL refer to the temperatures of the solid and liquid phases.

For the initial and boundary conditions of the thermal simulation within the study, the following specifications are applied:

-

The surface temperature of the hot water pipes is set to 323 K from 0:00 to 8:00, and an adiabatic boundary condition is applied from 8:00 to 24:00.

-

The floor surface is designated as the mixed thermal boundary, with an ambient temperature of 288 K. The heat transfer coefficient is measured at 8.72 W/m2·K, while the external radiation coefficient stands at 0.94.

-

The bottom insulation layer is considered an adiabatic boundary, and thermal losses are neglected.

Verification of numerical model

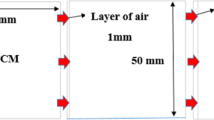

To ensure that the outcomes of numerical simulations are independent of the mesh count and time step, comparisons were conducted using three different mesh counts (13407, 29168, 64711) and three time-steps (5, 10, 20s). As depicted in (Fig. 3a, b), the temperature trends of the floor during the heating process for Case-1 indicate that a mesh count of 29,168 and the time step of 10 s adequately meet the requirements, balancing precision and efficiency.

Figure 3c presents the model validation results, which are based on the experimental conditions reported in reference37, and the results show that the discrepancy between the simulation results, the referenced simulation outcomes. In the experimental verification, due to the inability to reproduce the initial and boundary conditions of the experiment accurately, the deviation of the simulation results is slightly large in the initial stage. However, after 90 min, the simulation results fit well with the reference results, and the deviation rate is less than 2%.

(a) Grid independence, (b) Time step independence, (c) Experimental verification by previous research results37.

Data collection and analysis procedure

In this study, data were simulated and exported using FLUENT software, with the following key parameters monitored:

-

Phase change and temperature contour maps: Analyzed the PCM phase change process and floor temperature distribution, providing intuitive thermal state data.

-

PCM liquid fraction and temperature variation: Monitored the liquid phase ratio during the phase change process, evaluated the thermal energy storage capacity of the PCM and its impact on system performance, and tracked temperature variations to analyze thermal response characteristics under different designs and operating conditions.

-

Floor surface temperature variation and structural layer temperature distribution: Analyzed the temperature variations on the floor surface and within the structure, assessing the thermal comfort and temperature control effects of the system.

-

Heat flux: Analyzed the heat flow through the floor, evaluating the thermal transfer efficiency.

The data analysis method involves trend analysis of time-series data to evaluate thermal response and energy efficiency, comparing thermal behaviors under different conditions, with a focus on analyzing the thermal energy storage and temperature control performance of PCM under different encasement shapes.

Results and discussion

Thermal States of PCMs

The contour map in Fig. 4 illustrates the melting and solidification evolution of PCM in all cases, providing an intuitive visualization of the heat storage mechanism. The initial state of all cases is complete melting prior to the commencement of heating at 0 h. Subsequently, PCM initiates melting from the vicinity of the water pipe, gradually spreading throughout as the heating process advances. The melting rate of Case-1 is observed to be the highest at 4 h, while that of Case-5 is found to be the lowest. This can be attributed to the gradual elongation of the long axis in oval casings, resulting in an increased horizontal distance between the PCM and hot water pipe, thereby impeding efficient heat transfer. Consequently, by the end of the heating stage, both Case-4 and Case-5 still have un-melted PCM located at their respective ends. At the heat release stage, all cases exhibited a solidification trend from top to bottom, with PCM under the hot water pipe showing the slowest melting rate. It can be observed at 20 h that the more complete overall melting of the PCM is achieved when the short axis of the oval casing is shorter. This phenomenon can be attributed to the obstruction caused by the hot water pipe, preventing downward transfer of cold load from reaching below. Consequently, a shorter short shaft results in less PCM beneath the hot water pipe and facilitates easier melting. This means that the PCM encasement changes from a circular shape to an elliptical shape, addressing the issue of insufficient phase change rate of PCM at the bottom of the hot water pipe. However, as the long axis of the ellipse increases, the phase change rate of the PCM at both ends of the encasement also decreases.

The PCM liquid phase fraction is illustrated in (Fig. 5a). It can be observed from the figure that the melting behavior of PCM increased rapidly after heating initiation in all cases, with Case-1 exhibiting the highest melting rate and a trend similar to that of Case-2. Although slightly slower than the first two cases, Case-3 also achieved nearly complete melting by the end of the heat storage stage. The melting rate of Case-5 is relatively slow during the initial heating stage, but it surpasses that of Case-4 at 6.5 h and continues to increase until it reaches its maximum liquid fraction at 8.5 h. This phenomenon can be attributed to the combination of Case-5’s PCM casing and the hot water pipe, which facilitates the early release of heat from the hot water pipe to the mortar layer while simultaneously heating up the PCM. As a result, rapid heating of the mortar layer accelerates PCM melting and provides additional heat for another 0.5 h after cessation of heating. During the cooling phase, the liquid phase fraction exhibited a consistent decreasing trend. Between 21 h and 22 h, all cases sequentially achieved complete solidification, with Case-5 being the first and Case-1 being the last.

Figure 5b shows the variation trend of PCM average temperature. With the advance of the heating stage, the temperature of PCM rises and shows a decreasing trend of temperature rise from Case-1 to Case-5. This is because as the elliptic long axis of the casing becomes longer, the position distribution of PCM is farther away from the heat source pipe, resulting in a lower overall temperature rise rate. At 8 h, the PCM temperature drops rapidly under the action of the huge temperature difference between the indoor air and the floor layer. At 9 h, the PCM phase transition temperature decreases to 308 K, at which point PCM changes from sensible heat to latent heat and slows down the temperature decline for a long time. From 21 h to 22 h, Combined with the above analysis of liquid phase fraction, this is because PCM has reached complete solidification in this period, which means the end of the latent heat release stage, so the overall cooling rate of PCM increases.

Dynamic temperature distribution

Temperature contour maps

The contour map in Fig. 6 illustrates the temperature evolution of the floor structure layer during the heating and cooling stages. After starting heating, The PCM of Case-1 demonstrates a homogeneous temperature distribution due to the concentric circular positioning relationship between the PCM encasement and the hot water pipe. Other Cases show that with the increase of the long axis of the oval casing, the temperature rises of the PCM at the left and right ends of the casing become slower. Conversely, as the short axis decreases, there is a faster temperature increase in the mortar layer. This is because under the influence of PCM thermal resistance, the thinner the PCM above the hot water pipe, the more easily the heat is transferred to the mortar layer. From the cooling stage, under the action of PCM latent heat release, the high temperature region is concentrated in the PCM position. The temperature release rate in the floor structural layer increases progressively from Case-1 to Case-5. This suggests that, compared to the original Case-1, as the short axis of the elliptical PCM encasement is reduced and the thickness of the floor structural layer gradually decreases, it positively facilitates heat transfer to the floor surface.

Average temperature of floor surface

The floor surface temperature is a crucial parameter for determining indoor comfort and serves as the foundation for evaluating the performance of radiant heating floors. Figure 7 illustrates the variation curve of the average floor surface temperature. According to the ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-202340, the comfortable temperature range for radiant floor heating is between a minimum of 19 °C (292.15 K) and a maximum of 29 °C (302.15 K), with 24 °C (297.15 K) being recognized as the most comfortable temperature. This reference range is shown in the Fig41.

From the heating stage, the floor surface temperature rises more obviously with the shorter the oval half-shaft of the casing. Using an optimal temperature of 297.15 K as a reference, compared with the original Case-1 (at 8.3 h), Case-5 is 7 h earlier (at 1.3 h), Case-4 is 4.4 h earlier (at 3.9 h), Case-3 is 1.9 h earlier (at 6.4 h), and Case-2 is 0.6 h earlier (at 7.7 h). The maximum temperature increase is also obvious, with Case-5 rising to 301.3 K, Case-4 rising to 298.6 K, Case-3 rising to 297.7 K and Case-2 rising to 297.5 K, which are respectively 4.1 K, 1.4 K, 0.5 K and 0.3 K higher than 297.2 K in the original Case-1. This means that the optimized elliptical casing design can improve the thermal response rate of the floor during the heating phase. After the heating is stopped, the floor surface temperature experiences a sharp decline due to the influence of temperature difference, with a greater decline rate observed as the temperature difference increases. At 9 h, the release of latent heat from PCM slows down this decline rate until it eventually falls below the lower limit of comfortable temperature at 292.15 K after 20 h. At 24 h, it becomes evident that each case exhibits a trend towards lower minimum temperatures as the thickness of the floor structure layer decreases. This phenomenon can be primarily attributed to the progressively thinner vertical thickness of PCM resulting from a shortened short half-axis in an elliptical casing, facilitating heat dissipation.

Spatial temperature distribution

The spatial dynamic distribution of floor surface temperature is illustrated in (Fig. 8). The temperature ranges from 288 to 303 K, and the color contrast indicates the magnitude of temperature change, and the degree of temperature fluctuation. Comparison reveals that as the short half-axis of the oval encasement decreases, there is a gradual increase in floor temperature fluctuations within a span of 24 h. Notably, Case-4 and Case-5 exhibit an uneven horizontal temperature distribution during the heating stage, with higher temperatures observed at the center and lower temperatures at both ends, resulting in poor comfort conditions. This phenomenon can be attributed to the shortened short half-axis of the oval encasement facilitating easier heat transfer from hot water pipes to directly above them on the floor surface compared to its lateral sides.

Figure 9 shows a comparison of the distribution of floor surface temperature data, and the temperature difference (ΔT) between the highest and lowest points on the floor is introduced as a measure of the amplitude of temperature fluctuations. It is observed that Case-1 exhibits the most stable temperature fluctuations throughout the day, with a total temperature range of only 5.64 K. As the short semi-axis of the elliptical encasement is shortened, there is a tendency for larger fluctuations with higher highs and lower lows. Compared to the original case, the temperature fluctuations in the other cases have increased by 0.52 K (Case-2), 1.28 K (Case-3), 2.58 K (Case-4), and 5.43 K (Case-5). This means that the optimization of the elliptical PCM encasement has a negative effect on suppressing the floor temperature fluctuations. However, in order to balance comfort and cost-effectiveness, the increase in temperature fluctuations in Case-2 (0.52 K) and Case-3 (1.28 K) can be considered acceptable.

Heat flux analysis

The variation curves of floor surface heat flux in each case are illustrated in (Fig. 10a), demonstrating a correspondence between the heat flux variation and temperature trend. During the heating stage, as the short axis of the oval casing is shortened, the transfer of heat from the hot water pipe to the floor surface becomes more efficient, resulting in higher temperatures and greater temperature differences. Additionally, there is also an increase in peak heat flux. In comparison to the peak value of 126.22 W/m2 in Case-1, the peak values show relatively smaller increases for Case-2 and Case-3, with increments of only 0.89% (127.34 W/m2) and 0.90% (129.57 W/m2), respectively. However, there is a significant increase in the peaks for Case-4 and Case-5, which rise by 9.06% (137.65 W/m2) and an impressive 31.99% (166.60 W/m2), respectively. The cooling phase also showed the same downward trend as the temperature.

A comparison of average floor surface heat fluxes over a 24 h period is shown in (Fig. 10b). With the shortening of the short axis of the oval casing, the average heat flux decreases first and then increases. Among them, the average heat flux of Case-3 is the lowest, 87.55 W/m2, 0.80% lower than that of Case-1 in the original state, which means that Case-3 is the most energy saving.

Conclusions

To study the influence of encasement shape on the thermal performance of RFHSs integrated with PCM, based on CFD numerical simulation, the encasement shape is changed to reduce the thickness of the floor mortar layer on the basis of the concentric circle arrangement of PCM casing and hot water pipe, so as to improve the thermal performance of the floor and save the construction cost. The thermal state of PCM, temperature evolution of floor structure layer, spatial distribution of floor surface temperature, and change in heat flux are analyzed. The conclusion is as follows:

-

As the short shaft length (a) of the oval encasement approaches the pipe radius (r), there is a gradual decrease in both the utilization rate and average temperature of PCM.

-

The response time of the floor surface temperature is accelerated with the shorter oval casing shaft, facilitating enhanced heat conduction from the PCM layer to the mortar layer and consequently reducing the time required to achieve optimal floor temperature.

-

With the reduction in the short axis length of the oval PCM encasement, there is an increased temperature difference on the floor surface over time, resulting in a larger range of temperature fluctuations. When a ≤ 1.25r, there is a more pronounced uneven temperature distribution horizontally within the simultaneous segment, leading to lower comfort levels.

-

Considering both comfort and cost-effectiveness, the case where a = 1.5r (Case-3) exhibits the best overall performance. Compared to the original concentric casing, it achieves an earlier floor surface optimal temperature by 1.8 h, with only a slight increase of 1.28 K in temperature fluctuation difference. The average heat flux decreases by 0.8%, the mortar usage is reduced by 13.6%, and the thickness of the mortar layer is reduced by 16.7%. This indicates that this case enhances both thermal performance and economic efficiency.

Although this study has improved the performance of the encased PCM radiant floor heating system by changing the encasement shape, factors such as different floor types, climate conditions, and PCM material properties may still affect the system’s thermal performance and economic efficiency. Future research will investigate the impact of these factors on the study’s conclusions to enhance their generalizability. For instance, different floor structures and climate conditions may alter heat conduction and energy efficiency, while selecting the appropriate PCM is also crucial for system performance. Therefore, we will expand the research to consider the effects of these variables on the system. In addition, future work will focus on experimental studies of elliptical PCM casings to address the production and installation complexities in practical applications.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Hu, C. X., Zhang, G., Meng, X. & He, F. Influence of color reflectance on the thermal performance of building facades: A factor model-based detective analysis case studies in thermal engineering 66 105793. (2025).

Gao, Y., Ge, L. M. & Meng, X. Employing the spray system to improve the regional thermal environment in outdoor open space. Urban Clim. 59, 102266 (2025).

Meng, X. Analysis on rotation timing of dynamic rotating latent-energy-storage envelope (RLESE). Dev. Built Environ. 19, 100498 (2024).

Xu, T. et al. Development of diatomite-based shape-stabilized composite phase change material for use in floor radiant heating. J. Mol. Liq. 348, 118372 (2022).

Fu, W. et al. Preparation and properties of phase change temperature-tuned composite phase change material based on sodium acetate trihydrate–urea/fumed silica for radiant floor heating system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 162, 114253 (2019).

Ge, W. Y., Zou, J. L. & Meng, X. Thermal performance improvement of spherical encapsulated phase-change material by the metal fins. Energy Rep. 13, 2384–2392 (2025).

Jin, X., Yang, J., Li, M., Huang, G. & Lai, A. C. K. Experimental and numerical study on the thermal energy storage performance of a novel phase-change material for radiant floor heating systems. Build. Environ. 223, 109491 (2022).

Xie, N. et al. Enhanced thermal performance of Na2HPO4·12H2O composite phase change material supported by sepiolite fiber for floor radiant heating system. J. Build. Eng. 56, 104747 (2022).

Lee, J., Wi, S., Jeong, S. G., Chang, S. J. & Kim, S. Development of thermal enhanced n-octadecane/porous nano carbon-based materials using 3-step filtered vacuum impregnation method. Thermochim. Acta 655, 194–201 (2017).

Baccega, E., Bottarelli, M. & Cesari, S. Addition of granular phase change materials (PCMs) and graphene to a cement-based mortar to improve its thermal performances. Appl. Therm. Eng. 229, 120582 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. A phase change thermal storage material and its performance for floor electric heating system. J. Energy Storage 59, 106518 (2023).

Sun, W., Zhang, Z., Wu, Z. & Xu, Y. Numerical modeling and optimization of annual thermal characteristics of an office room with PCM active–passive coupling system. Energy Build. 254, 111629 (2022).

Li, G., Zhang, P., Xu, G. & Gantumur, T. Experimental study of advanced phase change materials to optimise the thermal storage performance of radiant floors: towards a low-carbon energy system for grassland pastoral settlements. Constr. Build. Mater. 455, 139220 (2024).

Cesari, S., Emmi, G. & Bottarelli, M. A weather forecast-based control for the improvement of PCM enhanced radiant floors. Appl. Therm. Eng. 206, 118119 (2022).

Ju, H. et al. Heating performance of PCM radiant floor coupled with horizontal ground source heat pump for single-family house in cold zones. Renew. Energy 235, 121306 (2024).

Zhou, G. & He, J. Thermal performance of a radiant floor heating system with different heat storage materials and heating pipes. Appl. Energy 138, 648–660 (2015).

Cheng, W., Xie, B., Zhang, R., Xu, Z. & Xia, Y. Effect of thermal conductivities of shape stabilized PCM on under-floor heating system. Appl. Energy 144, 10–18 (2015).

Huang, K., Feng, G. & Zhang, J. Experimental and numerical study on phase change material floor in solar water heating system with a new design. Sol. Energy 105, 126–138 (2014).

Feng, G. et al. DSC test error of phase change material (PCM) and its influence on the simulation of the PCM floor. Renew. Energy 87, 1148–1153 (2016).

Plytaria, M. T., Tzivanidis, C., Bellos, E. & Antonopoulos, K. A. Energetic investigation of solar assisted heat pump underfloor heating systems with and without phase change materials. Energy. Conv. Manag. 173, 626–639 (2018).

Plytaria, M. T., Tzivanidis, C., Bellos, E. & Antonopoulos, K. A. Parametric analysis and optimization of an underfloor solar assisted heating system with phase change materials. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progress 10, 59–72 (2019).

Larwa, B., Cesari, S. & Bottarelli, M. Study on thermal performance of a PCM enhanced hydronic radiant floor heating system. Energy 225, 120245 (2021).

Chen, W. et al. Experimental and numerical investigations on radiant floor heating system integrated with macro-encapsulated phase change material. Energy 282, 128375 (2023).

Jin, X. & Zhang, X. Thermal analysis of a double layer phase change material floor. Appl. Therm. Eng. 31, 1576–1581 (2011).

Sun, W., Zhang, Y., Ling, Z., Fang, X. & Zhang, Z. Experimental investigation on the thermal performance of double-layer PCM radiant floor system containing two types of inorganic composite PCMs. Energy Build. 211, 109806 (2020).

Zhao, M., Zhu, T., Wang, C., Chen, H. & Zhang, Y. Numerical simulation on the thermal performance of hydraulic floor heating system with phase change materials. Appl. Therm. Eng. 93, 900–907 (2016).

González, B. & Prieto, M. M. Radiant heating floors with PCM bands for thermal energy storage: A numerical analysis. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 162, 106803 (2021).

Jiang, T. et al. Experimental and numerical study on the heat transfer performance of the radiant floor heating condenser with composite phase change material. Appl. Therm. Eng. 213, 118749 (2022).

Xia, Y. & Zhang, X. S. Experimental research on a double-layer radiant floor system with phase change material under heating mode. Appl. Therm. Eng. 96, 600–606 (2016).

Xu, Y., Sun, B. B., Liu, L. J. & Liu, X. Y. The numerical simulation of radiant floor cooling and heating system with double phase change energy storage and the thermal performance. J. Energy Storage 40, 102635 (2021).

Sun, B., Xu, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhao, H. & Liu, X. Simulation and optimization research of double energy storage floor based on heat transfer characteristic of phase change materials. J. Energy Storage. 51, 104452 (2022).

Sui, X., Liu, H., Du, Z. & Yu, S. Developing a TRNSYS model for radiant cooling floor with a pipe-embedded PCM layer and parametric study on system thermal performance. J. Energy Storage 71, 108024 (2023).

Yu, Q., Sun, B., Li, C., Yan, F. & Li, Y. Analysis of heat charging and release processes in cascade phase change materials energy storage floor heating systems: performance evaluation. J. Energy Storage 78, 110020 (2024).

Lu, S., Zhao, Y., Fang, K., Li, Y. & Sun, P. Establishment and experimental verification of TRNSYS model for PCM floor coupled with solar water heating system. Energy Build. 140, 245–260 (2017).

Lu, S., Xu, B. & Tang, X. Experimental study on double pipe PCM floor heating system under different operation strategies. Renew. Energy 145, 1280–1291 (2020).

Lu, S. et al. Model establishment and operation optimization of the casing PCM radiant floor heating system. Energy 193, 116814 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Thermal performance and optimization of a casing pipe solar energy storage floor with phase change material. Energy Build. 247, 111167 (2021).

Wang, Z., Gao, W. & Gao, Y. Influence of hot water pipe position on the performance of radiant floor heating systems integrated with PCM. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 61, 105030 (2024).

Wang, Z., Gao, W. & Gao, Y. Effect of the integration mode of phase change materials on thermal performance of radiant floor heating systems. J. Energy Storage 110, 115275 (2025).

American Society of Heating. Refrigerating and air-conditioning engineers. ANSI/ASHRAE standard 55-2023: thermal environmental conditions for human occupancy. ASHRAE (2023).

Zhong, T. & Meng, X. Effect of air temperature in indoor transition spaces on the thermal response of occupant during summer. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 919 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W., W.G. and Y.G. wrote the main manuscript text, and they prepared all figures. Z.W. and W.G. done the experimental design and completed the experiment. W.G., J.S. and Y.G. supervised. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Gao, W., Sun, J. et al. Optimizing the axis ratio of elliptical PCM encasement for enhanced thermal performance in radiant floor heating systems. Sci Rep 15, 9025 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93789-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93789-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Thermoanalytical and Physical Characterization of Animal Fat and Commercial Organic Phase Change Materials

International Journal of Thermophysics (2026)