Abstract

Troponin is a crucial biomarker in the emergency department (ED). Current evidence does not support differentiation between an uncomplicated tachyarrhythmia and significant coronary artery disease (CAD). The aim of the present study was to assess the use of troponins to predict CAD and mortality in patients with acute atrial fibrillation/flutter (AF/AFL). This cohort study included 3,425 consecutive episodes with AF/AFL treated at the ED of the Medical University of Vienna between 2012 and 2024. Coronary angiography was performed in 251 cases. Patients were grouped according to the troponin levels (ng/L): 0–4; 5–14; 15–28; 29–51 and ≥ 52. Outcomes were significant CAD and mortality. Of all cases (n = 3,425), coronary angiography was performed within 30 days in 251 (7%); 115 (46%) had significant CAD. The rate increased with rising troponin levels: baseline troponin, ng/L, %: 5–14: 32, 15–28: 38, 29–51: 47, ≥ 52: 57; p = 0.028; serial troponin, ng/L, %: 5–14: 15, 15–28: 19; 29–51: 54; ≥ 52: 66; p < 0.001. Sensitivity for significant CAD at 5 ng/L was 99%; specificity at ≥ 52 ng/L was 77% and increased to > 92% at ≥ 92 ng/L. 713 patients (21%) died in an observation time of 13,771 years. A troponin value ≥ 15 ng/L was significantly associated with all-cause mortality. Prevalence of significant CAD increases with rising and dynamic troponin levels. Troponin thresholds for further diagnostics or interventions may be different in AF/AFL than in the general population. Elevated troponin levels at baseline and in subsequent measurements as well as significant changes are associated with an increased all-cause mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrythmia worldwide and represents a substantial health care burden1. Recent studies have underscored its relevance across various patient groups and its impact on treatment strategies, cardiovascular risk, and postoperative outcomes2,3,4. As AF research continues to evolve, biomarkers are increasingly being explored for risk stratification: While novel biomarkers are being assessed and evaluated, established ones—such as cardiac troponins—are undergoing renewed investigation5,6.

Cardiac troponin is a valid, globally used biomarker for myocardial injury. It is essential for the detection of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) in patients with clinical symptoms of myocardial ischemia but non-specific ECG findings7,8,9.

However, elevated troponin levels can occur in various clinical conditions10,11,12,13. There is no guidance on interpretation in the absence of typical symptoms of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). This gap in evidence is of clinical importance as the combination of non-ischemia-specific symptoms and simultaneously elevated troponin can be observed frequently and represents a challenge for physicians6,14.

AF and atrial flutter (AFL) are common conditions in which symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia and elevated troponin levels can occur. It is the most common tachyarrhythmia in the emergency department (ED). Therefore, structured and efficient approaches are needed to provide sufficient and safe emergency treatment. Patients acutely presenting to an ED with AF show a broad range of symptoms such including thoracic discomfort or pain15. Given the similar risk profile and overlapping symptoms of AF and cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease (CAD), clinical decision-making in an emergency setting remains a challenge. Optimal management, that avoids the risks of possible side effects of further (invasive) investigations in uncomplicated cases, but ensures rapid and safe further diagnostics in high-risk patients, is crucial16,17,18.

Even the well-established high sensitivity troponin tests do not yet allow a clear differentiation between a typical uncomplicated tachyarrhythmia and a significant CAD in patients with acute AF/AFL. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the use of cardiac troponins to predict CAD and mortality in these patients.

Methods

Study design and study patients

In this cohort study, consecutive episodes with AF/AFL treated for acute symptoms in the ED of the Medical University of Vienna between 2012 and 2024 were analysed. For this analysis, we included all patients with at least one available valid troponin measurement (n = 3,425). Patients without such results (e.g., external laboratory tests or unvalidated assays) were excluded. Additionally, patients with cardiac arrest and subsequent AF/AFL and those meeting the diagnostic criteria for ST-elevation MI were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria (no. 1568/2014). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

AF/AFL and Cath lab registry

Since 2011, a comprehensive database has been maintained in which all episodes with AF/AFL treated at the Department of Emergency Medicine of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, are recorded. About 90,000 patients are treated at this tertiary care ED each year, and up to 600 of these are diagnosed with AF or AFL. Details of the registry have already been published previously19. In brief, all patients with AF/AFL, confirmed by a 12-lead ECG, are included in the registry after informed consent. Clinical baseline characteristics, vital parameters and laboratory values are documented by study nurses. To date, over 4,000 cases of AF and AFL have been documented. The registry is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03272620).

Data from the AF/AFL registry were combined with the Vienna Cath Lab Registry. The Vienna Cath Lab Registry consecutively includes all patients presenting to the cardiac catheterization laboratory of the Medical University of Vienna since 2010. Approval was provided by the local ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK 2043/2021). Up to 4,000 coronary angiographies and 1,800 percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) are performed annually. The registry systematically records predefined clinical baseline characteristics, laboratory analysis during hospitalization and detailed information on coronary angiography and interventions.

Troponin measurements

At least one troponin measurement (single measurement at baseline [troponin 1] or serial measurement [troponin 2]) was available for all included episodes. Only high sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) assays are used at the study centre. The measurements are performed by the accredited and certified associated central laboratory according to fully standardised procedures. The hs-cTnT assay (Roche Elecsys 2010 high-sensitivity troponin T, Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) has a 99th percentile concentration of 14 ng/L with a corresponding co-efficient of variation (CV) of 10% at 13 ng/L. Limit of blank (LoB) and limit of detection (LoD) have been determined to be 3 ng/L and 5 ng/L.

Measurement of hs-cTnT and subsequent treatment were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)8. In the present analysis, hs-cTnT was divided into 5 groups: 0–4 ng/L; 5–14 ng/L; 15–28 ng/L; 29–51 ng/L and ≥ 52 ng/L. Troponin groups were chosen in accordance with LoD (5 ng/L), 99th percentile concentration (14 ng/L) and limit of NSTEMI rule in (≥ 52 ng/L). Group one (0–4 ng/L) and two (5–14 ng/L) were regarded as non-significant hs-cTnT increase (below the upper reference limit). An absolute change in the initial hs-cTnT value of ≥ 5 ng/L was considered a significant troponin dynamic.

Outcomes

Coronary angiography and definition of CAD

Coronary angiography was performed based on a shared decision-making process, incorporating clinical indications including symptoms suggestive of ischemia, troponin levels, and individual patient characteristics. The procedure was conducted via radial or femoral access at the discretion of the operator. The presence of hemodynamically relevant obstructive CAD was the primary criterion for proceeding with PCI, with functional assessment or intracoronary imaging utilization when necessary to guide decision-making. Stent selection, anticoagulant strategies, and post-procedural management was determined by the operator in collaboration with the treating department. All procedures were conducted by experienced interventional cardiologists, ensuring adherence to contemporary guidelines8.

Obstructive CAD was defined as a visual lumen narrowing of > 50% in the left main coronary artery (LMCA) and > 70% in any other coronary artery, or as determined by a positive physiological test. Angiographic findings were independently reviewed by an experienced interventional cardiologist. In case of discrepancy or noncompliance with the initial assessment, a third-party evaluation was conducted to ensure accuracy. Any intervention, including plain old balloon angioplasty, drug coated balloon and/or implantation of one or multiple stents, was defined as percutaneous intervention (PCI).

Mortality

The mortality data (‘all-cause death’) were provided by the Austrian death registry, which is maintained by the National Central Statistical Office (Statistik Austria, Guglgasse 13, A-1110 Vienna). All patients documented by the Austrian death registry were included in the mortality analysis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables are described with absolute frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons were performed using a χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (if any expected cell count was less than five). Cox regression models to estimate associations between troponin levels and mortality were used. The effects are presented as hazard ratios (HR) together with the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Moreover, sensitivity and specificity analyses were performed for hs-cTnT thresholds. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For data analysis, STATA 17 for Mac and Excel for Mac, version 16.87, for creation of the presented figures GraphPad Prism 10 for macOS, version 10.2.2 (341) were used.

Results

The characteristics of the overall study cohort and the patients undergoing coronary angiography are shown in Table 1. An inclusion flow chart of the study population is provided in Fig. 1.

Troponin levels

For all cases (n = 3,425) there was at least one hs-cTnT measurement available. Troponin values of two consecutive measurements were available for 1,727 (50%) cases (troponin 1: median 15; IQR 9–28; troponin 2: median 21; IQR 12–44). A significant troponin change of ≥ 5 ng/L was found in 626 (18%) cases.

Coronary angiography

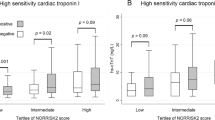

Troponin values on admission were available for all 251 episodes where coronary angiography was performed. Information on troponin dynamics was available for 165 (66%). Significant CAD was detected in 115 (46%) episodes. The numbers of coronary angiographies performed increased with increasing troponin 1 levels were as follows: 0–4 ng/L: 0 (0%); 5–14 ng/L: 39 (3%); 15–28 ng/L: 76 (8%); 29–51 ng/L: 47 (11%); and ≥ 52 ng/L: 88 (23%). The prevalence of significant CAD also increased with increasing troponin levels. This applied to both troponin values: troponin 1, ng/L: 5–14: n = 11 (32%), 15–28: n = 31 (38%), 29–51: n = 22 (47%), ≥ 52: n = 51 (57%); p = 0.028. The same was observed for troponin 2 values, ng/L: 5–14: n = 2 (15%), 15–28: n = 6 (19%); 29–51: n = 13 (54%); ≥ 52: n = 63 (66%); p < 0.001. Detailed results are shown in Table 2; Fig. 2.

Among 50 patients diagnosed with significant CAD who did not undergo acute PCI, a conservative management approach was chosen for 22 patients based on clinical evaluation. This decision was primarily due to factors such as non-viability in cases of chronic total occlusion (CTOs), small distal stenoses without hemodynamic relevance, or severe comorbid conditions. 14 patients were referred for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) following interdisciplinary heart-team decision, while elective PCI was planned for the remaining 14 patients.

In 112 cases (68%), a change in troponin level of ≥ 5 ng/L was observed between the first and subsequent troponin measurement. 61% of these had significant CAD compared to 30% without such troponin dynamics (p < 0.001).

Accuracy of troponin thresholds

The sensitivity of a troponin threshold of 5 ng/L for rule out of significant CAD was 99%. The specificity of a troponin threshold ≥ 52 ng/L for rule in was 77%. The specificity for CAD rule in increased to > 92% using a troponin threshold of ≥ 92 ng/L.

Mortality

During the follow up period, 713 (21%) patients died. The cumulative observation time (troponin 1) from admission to end of follow up was 13,771 patient years (incidence rate 0.05176 per year). In the multivariate analysis, a troponin 1 level of ≥ 15 ng/L was significantly associated with death (HR 2.90; CI95% 2.32–3.62; p < 0.001) after adjustment for chronic heart failure, chronic kidney disease, chronic CAD, and abnormal heart rate. The same was seen in a troponin 1 level ≥ 29 ng/L (HR 4.65; CI95% 3.65–5.92; p < 0.001) and ≥ 52 ng/L (HR 4.8; CI95% 3.76–6.15; p < 0.001). Probability of survival according to troponin levels at baseline is shown in Fig. 3.

Of the 1,727 patients who had two troponin measurements, 440 (25%) died during a follow-up period totalling 6,955 patient years (incidence rate 0.0632 per year). A troponin 2 value ≥ 15 ng/L was significantly also associated with death (HR 2.59; CI95% 1.85–3.64; p < 0.001) after adjustment for chronic heart failure, chronic kidney disease, chronic CAD and abnormal heart rate. The same was seen in a troponin 2 level ≥ 29 ng/L (HR 4.03; CI95% 2.85–5.69; p < 0.001) and ≥ 52 ng/L (HR 3.70; CI95% 2.63–5.20; p < 0.001).

In episodes with significant troponin dynamics (≥ 5 ng/L; n = 626, 36%), 212 (34%) deaths were observed compared to 228 (21%) deaths in cases without such troponin dynamics (n = 1101, 64%). Thus, an absolute change in troponin value of ≥ 5 ng/L was independently associated with an increased risk of death (HR 1.40; CI95% 1.147–1.70; p = 0.001).

Discussion

The present study provides several important insights regarding troponin use for risk stratification of CAD and mortality in patients with AF/AFL: Elevated troponin levels are common in acute AF/AFL. There is a significant association between elevated troponin levels and the need for coronary angiography and the incidence of significant coronary stenosis. This also applies to troponin dynamics during acute treatment. Troponin cut-off values with a sensitivity and specificity equipotent to those used in the diagnosis of MI may be in different ranges. Elevated troponin levels on admission, subsequent measurements and significant dynamic changes are each associated with increased all-cause mortality. Given the lack of specific guidelines, these findings emphasise the need for tailored protocols to improve clinical decision-making and patient outcomes.

An increase in troponin levels can be observed in various conditions10,11,12. AF is a common cause of elevated troponin but routine testing is generally not recommended20. Such troponin increases in patients with AF/AFL without symptoms of an ACS pose a diagnostic challenge21. This study shows that a in a significant proportion of AF/AFL episodes (51%) elevated troponin values above the 99th percentile can already be found on admission, with 18% showing a significant dynamic change (≥ 5 ng/L) over time. This observation is consistent with previous data suggesting that an arrhythmia itself may lead to an increase in troponin levels through mechanisms such as increased myocardial oxygen demand and reduced coronary perfusion22.

The association between troponin levels and CAD in AF/AFL is noteworthy as patients with AF/AFL frequently undergo angiography6,20,23. In this study, angiography within 30 days was performed in 251 episodes. In 115 (46%) cases significant CAD was found, and in 65 cases (26%) acute PCI was required. The rate of significant CAD increased with troponin levels from 32% at troponin levels of 5–14 ng/L to 57% at a troponin level of > 52 ng/L. Compared to the previously published prevalence of CAD in patients with AF (17–47%)24,25,26,27,28, the observed rates appear quite high. The high CAD rates in this study may reflect the more acute nature of a symptomatic, tachycardic ED cohort and emphasize the need for careful ACS screening in this population19.

Consistent with the ESC guidelines on ACS, the dynamic nature of troponin changes also appears to be of clinical significance in patients with acute AF/AFL8. The present study showed that a dynamic change in troponin level was significantly (p < 0.001) associated with a higher prevalence of significant CAD: 30% (< 5 ng/L; n = 16) versus 61% (≥ 5 ng/L, n = 68). This suggests that troponin dynamics in acute AF/AFL in the ED may be of equal or even greater diagnostic importance than using the absolute values of individual troponin measurements alone. A potential reason for the discrepancy between the number of significant troponin level fluctuations and the number of coronary angiographies performed is the lack of clear guidance on managing AF patients with elevated and dynamic troponin levels. As the prevalence of underlying CAD in AF has been unclear, troponin fluctuations have often been attributed primarily to the tachyarrhythmia itself without considering significant CAD.

Considering the recent ACS guidelines, a direct exclusion of ACS in patients with acute AF/AFL in the ED seems possible with a similar troponin cut-off of < 5 ng/L (sensitivity 99%). However, diagnosis of ACS seems to be more complex: The troponin threshold value of 52 ng/L, which is usually used for NSTEMI diagnosis, had a significantly lower specificity of only 77%. Only at a threshold value of ≥ 92 ng/L the specificity was above 90%. This finding suggests that higher troponin thresholds may be required for accurate diagnosis of NSTEMI in AF/AFL patients. This seems plausible, given the more complex troponin profile in ACS patients with concomitant AF/AFL.

In addition to the incidence of CAD, the present study also investigated the relationship between elevated troponin levels and mortality in patients with AF/AFL. Elevated troponin levels, both at baseline and during the acute course, were significantly associated with increased all-cause mortality. This association remained significant after adjustment for potential confounders. This has already been described for several populations including emergency cohorts19. Vitolo et al. found that an increase in troponin was associated with a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and all-cause mortality in AF patients29. Paana et al. showed that a small increase in troponin levels was associated with higher short- and long-term all-cause mortality in patients with AF in the ED30. Moreover, the close association between AF, biomarker alterations such as the uric acid/albumin ratio, CAD and myocardial infarction which leads to unfavorable outcome has also already been demonstrated5.

In addition, a meta-analysis including a total of 22,697 AF patients, showed that an increase in troponin was independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and MACE31.

A novelty of this study is the reporting of an effect size of troponin dynamics during acute treatment in relation to the increase in mortality in patients with acute AF/AFL in the ED: Troponin changes > 5 ng/L were associated with an 40% higher risk of death (HR 1.40; CI95% 1.147–1.70; p = 0.001). 212 (34%) deaths were observed in cases with significant troponin dynamics (n = 626; 36%) compared to 228 (21%) in cases with changes in troponin-levels < 5 ng/L (n = 1101, 64%); p < 0.001. These results may emphasize the importance of serial troponin measurements in risk stratification of AF/AFL patients and the need for comprehensive treatment strategies that address both the arrhythmia and the underlying cardiovascular risk. The high prevalence of significant coronary stenosis and the high mortality as well as the known association between coronary heart disease and death also suggest a causal relationship in this group of patients with acute AF/AFL in an ED32.

Some key points could be of particular significance for clinical practice: Firstly, serial troponin measurements should be standard in the ED evaluation of patients with AF/AFL. Significant troponin dynamics (≥ 5 ng/L) should prompt further investigations for CAD. Secondly, sound troponin thresholds are needed to improve the diagnosis of ACS in patients with AF/AFL. Future research should focus on establishing AF/AFL-specific troponin cut-offs to support clinical decision-making. Multicenter studies are needed to identify and validate such troponin thresholds and dynamic monitoring strategies in patients with AF/AFL. Thirdly, patients with AF/AFL and elevated troponin levels should undergo comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment. Finally, there is a need for guidelines on the management of elevated troponin levels in patients with acute AF/AFL in the ED to ensure an evidence-based use of serial troponin measurements, adjusted cut-offs, and comprehensive risk stratification.

Strengths and limitations

Due to its design, the present study has some inherent limitations that need to be considered. These include the variability of individual patient profiles and differences in management both at the ED and at subsequent angiography. The decision for angiography was not standardized beyond the clinical guideline recommendations and the recorded information on the acute symptoms does not allow sufficient conclusions on indications to be drawn. As standardized protocols for managing AF patients with elevated troponin levels are lacking, the current clinical routine is a multifaceted evaluation that takes into account symptoms, troponin levels, and individual patient characteristics to make the decision for coronary angiography. The decision is made collaboratively, emphasizing a shared decision-making process. However, a clear strength is the large cohort of consecutive patients, which reduces the potential negative impact on conclusions drown. All included patients had troponin information available. Half of patients had two serial measurements. Other strengths are the novelty of some key aspects, especially within the specific population, the simple and robust methodology, and the results that not only pointing in the same direction but also seem plausible given the current state of medical knowledge. In particular, the outcome measurement of all-cause mortality provides additional robustness to the present findings, as death certificates are mandatory in Austria and are registered by a central, state-controlled office, which minimizes information bias. However, the single-center design limits the generalizability of the results to other settings and populations. Confirmation of the results in larger, multicenter studies would be ideal. Such studies would also allow the estimation of precise cut-off values for risk estimation and stratification.

Conclusion

Troponin elevation is common in AF/AFL. There is a significant association between increased troponin-T levels and the need for coronary angiography. The prevalence of significant coronary stenosis rises with increasing troponin levels and dynamics. Troponin cut-off values are possible in AF/AFL, but may lie in other ranges as those for NSTEMI diagnosis. Elevated troponin levels at baseline and in subsequent measurements as well as significant dynamics are each associated with increased all-cause mortality.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration. With the European association for Cardio-Thoracic surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/45/36/3314/7738779?login=true [cited 2024 Nov 4].

Şaylık, F., Çınar, T., Akbulut, T. & Hayıroğlu, M. İ. Comparison of catheter ablation and medical therapy for atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heart Lung 57, 69–74 (2023).

Hayıroğlu, M. İ. et al. Cardiac variables associated with atrial fibrillation occurrence and mortality in octogenarians implanted with dual chamber permanent pacemakers. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 34 (10), 2533–2539 (2022).

Orhan, A. L. et al. Atrial fibrillation as a preoperative risk factor predicts long-term mortality in elderly patients without heart failure and undergoing hip fracture surgery. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 67 (11), 1633–1638 (2021).

Selçuk, M. et al. Predictive value of uric acid/albumin ratio for the prediction of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with ST-Elevation myocardial infarction. Rev. Invest. Clin. 74 (3), 156–164 (2022).

Meshkat, N. et al. Troponin utilization in patients presenting with atrial fibrillation/flutter to the emergency department: retrospective chart review. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 4 (1), 25 (2011).

Thygesen, K. et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 126 (16), 2020–2035 (2012).

Byrne, R. A. et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 44 (38), 3720–3826 (2023).

Adams, J. E. et al. Cardiac troponin I. A marker with high specificity for cardiac injury. Circulation 88 (1), 101–106 (1993).

Jeremias, A. & Gibson, C. M. Narrative review: alternative causes for elevated cardiac troponin levels when acute coronary syndromes are excluded. Ann. Intern. Med. 142 (9), 786 (2005).

Nunes, J. P., Silva, J. C. & Maciel, M. J. Troponin I in atrial fibrillation with no coronary atherosclerosis. Acta Cardiol. (3), 345–346 (2004).

Bakshi, T. K. et al. Causes of elevated troponin I with a normal coronary angiogram. Intern. Med. J. 32 (11), 520–525 (2002).

Korff, S. Differential diagnosis of elevated troponins. Heart 92 (7), 987–993 (2006).

Agewall, S., Giannitsis, E., Jernberg, T. & Katus, H. Troponin elevation in coronary vs. non-coronary disease. Eur. Heart J. 32 (4), 404–411 (2011).

Long, B., Brady, W. J. & Gottlieb, M. Emergency medicine updates: atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 74, 57–64 (2023).

Kannel, W. B., Abbott, R. D., Savage, D. D. & McNamara, P. M. Coronary heart disease and atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. Am. Heart J. 106 (2), 389–396 (1983).

Zimetbaum, P. J. et al. Incidence and predictors of myocardial infarction among patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 36 (4), 1223–1227 (2000).

Friedman, H. Z., Weber-Bornstein, N., Deboe, S. F. & Mancini, G. B. J. Cardiac care unit admission criteria for suspected acute myocardial infarction in new-onset atrial fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 59 (8), 866–869 (1987).

Niederdöckl, J. et al. Cardiac biomarkers predict mortality in emergency patients presenting with atrial fibrillation. Heart 105 (6), 482–488 (2019).

Hindricks, G. et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J., ehaa612 (2020).

Notaristefano, F. & Cavallini, C. Atrial fibrillation and troponin elevation: it’s time to give up the Chase to diagnosis and step forward with prognosis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 99, 26–27 (2022).

Jaakkola, S. et al. Etiology of minor troponin elevations in patients with atrial fibrillation at emergency department–Tropo-AF study. JCM 8 (11), 1963 (2019).

Alghamry, A. et al. Predictors of significant coronary artery disease in atrial fibrillation: are cardiac troponins a useful measure. Int. J. Cardiol. 223, 744–749 (2016).

Crijns, H. J. et al. Serial antiarrhythmic drug treatment to maintain sinus rhythm after electrical cardioversion for chronic atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Am. J. Cardiol. 68 (4), 335–341 (1991).

Lip, G. Y. H. & Beevers, D. G. ABC of atrial fibrillation: history, epidemiology, and importance of atrial fibrillation. BMJ 311 (7016), 1361–1361 (1995).

Hohnloser, S. H. et al. Effect of Dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 (7), 668–678 (2009).

Kralev, S., Schneider, K., Lang, S., Süselbeck, T. & Borggrefe, M. Incidence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing first-time coronary angiography. PLoS ONE 6 (9), e24964 (2011).

Van Gelder, I. C. et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (15), 1363–1373 (2010).

Vitolo, M. et al. Cardiac troponins and adverse outcomes in European patients with atrial fibrillation: A report from the ESC-EHRA EORP atrial fibrillation general long-term registry. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 99, 45–56 (2022).

Paana, T. et al. Minor troponin T elevation and mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation presenting to the emergency department. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 51 (11), e13590 (2021).

Fan, Y., Zhao, X., Li, X., Li, N. & Hu, X. Cardiac troponin and adverse outcomes in atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 477, 48–52 (2018).

GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and National age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 392 (10159), 1736–1788 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and J.N.; methodology, J.N. and A.N.; software H.H.; validation, and H.H. and M.S.; formal analysis, H.H., investigation, S.G., E.S. and L.K.; resources, F.C., A.S., E.S. and L.K.; data curation, S.G., M.L., F.C., E.S. and L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G., E.S., M.S. and J.N.; writing—review and editing, A.N., M.S., J.N., A.S., N.B. and S.S.; visualization, J.N. and S.G.; supervision, H.D., A.S., J.N., H.H., M.S. and A.N.; project administration, J.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, S., Steinacher, E., Lutnik, M. et al. Troponin is associated with mortality and significant coronary artery disease in patients treated for atrial fibrillation in the emergency department. Sci Rep 15, 9268 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93855-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93855-z