Abstract

Through the analysis of electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra from patients with pigment gallstones, it was found that both Fe3+ and Cu2+ signals were detected in the gallstone powder, exhibiting relatively high intensity. The EPR signal for Fe(III) showed g = 4.18 and ΔHpp = 4.85 mT, presenting an asymmetric high-spin spectrum; for Cu(II), g‖=2.36 and g⊥=2.15 were observed. This study explored the relationship between bile pigments and Fe3+ /Cu2+ ions, noting that routine health examinations for gallstone patients typically do not include testing for heavy metal ions. Therefore, effective preventive measures against gallstone formation should be based on dietary habits, necessitating EPR studies to assess the levels of Fe3+ and Cu2+ in various food types. This paper discusses the morphology of pigment gallstones as well as the correlation between bile pigments and Fe3+ /Cu2+ ions, along with the impact of different food categories on pigment gallstones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biliary stones represent a significant health challenge faced by both industrialized and developing nations, closely associated with economic factors. The prevalence of this condition has markedly increased over recent decades1. Since the 1960s and 1970s, the incidence of gallstones in Western countries has risen from approximately 6% to nearly 20%2,3. This disease not only poses a threat to patient health but is also regarded as a substantial economic burden, second only to other gastrointestinal disorders; for instance, Germany alone performs over 170,000 cholecystectomies annually4.

A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying gallstone formation is essential for elucidating the intricate interplay between internal biological processes and external environmental factors. Despite ongoing research efforts in this field, numerous unknowns persist. Scientists are diligently working to establish connections among various elements including specific medical conditions, obesity, dietary habits, genetic predispositions, gender differences, and racial characteristics and the process of gallstone formation5,6. This process is complex and involves multiple interwoven risk factors.As a prevalent health issue, gallstone formation entails the development of biominerals within the gallbladder. These minerals primarily consist of core components such as cholesterol, bilirubin calcium, calcium carbonate, and calcium phosphate alongside various trace elements including aluminum, calcium, chromium, copper iron manganese among others. Bile serves as a natural fluid within the gallbladder that not only carries these elements but also facilitates their excretion processes7,8.The elevated copper content found in pigment-type gallstones may be attributed to the formation of bilirubin-copper complexes, which confer a characteristic black coloration to these stones9. Copper is integral to various metabolic processes within the body, with its primary excretion pathway involving transport through the liver into bile, followed by elimination via feces. This process also encompasses unabsorbed dietary copper. The absorption and retention of copper are modulated by dietary intake as well as physiological conditions. Although copper is an essential trace element necessary for maintaining normal physiological functions, excessive consumption can lead to adverse health effects. Elevated levels of copper are closely linked to liver and kidney damage, gastrointestinal discomfort, and neurotoxicity10. Therefore, addressing the issue of copper pollution is imperative. The sources of this pollution include industrial wastewater discharge, agricultural runoff, and the corrosion of copper-containing infrastructure. In pigment-type stones, iron exists in two primary forms: heme iron and non-heme iron11. Heme iron primarily originates from hemoglobin and myoglobin found in meat, poultry, and fish exhibiting higher absorption efficiency while non-heme iron is widely present in grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables but has relatively lower absorption rates that predispose individuals to stone formation.

Additionally, pathological conditions such as inflammation, infectious diseases, liver disease, starvation or excessive alcohol consumption may lead to elevated levels of iron; these serve as important reference indicators in clinical diagnosis12,13. Understanding the mechanisms underlying dietary absorption of both iron and copper and their relationship with health is vital for formulating appropriate dietary strategies aimed at preventing pigment-type gallstones14.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) technology serves as a powerful analytical tool with unique applications in detecting and identifying free radical metabolites15. These characteristic EPR signals not only confirm the existence and activity of free radicals during non-thermal processing but also reveal their potential impacts on food quality and safety. EPR technology demonstrates high sensitivity and accuracy in detecting free radical metabolites while providing robust technical support for research across various fields including biology, food science, and materials science.

The electronic paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy method employed in this study is distinguished by its extensive linear range, rapid analysis speed, low detection limits, capability for simultaneous multi-element detection, and ease of operation. This technique was utilized to conduct compositional identification and analysis of bilirubin stones in patients with gallstones. The primary focus of the research includes the swift and accurate identification of gallstone components, EPR determination of trace amounts of Fe3+ and Cu2+ within gallstones, as well as exploring the correlation between these ions and the constituents of gallstones. Additionally, based on dietary habits, this study aims to effectively prevent the occurrence of gallstones among residents in Jilin City by conducting EPR investigations into the Fe3+ and Cu2+ content present in various food types.

Methods

Collection of bile pigment stones

The samples were collected from Jilin City, Jilin Province, People’s Republic of China, between April 2019 and June 2020 at the Department of Surgery and the Digestive Center of Jilin City People’s Hospital. All patients provided informed consent for the collection and analysis of gallstones associated with cholelithiasis. A total of 58 patients who had continuously resided in Jilin City were included in this study. In previous reports16, a classification analysis was conducted on all gallstones. This study will specifically focus on the analytical assessment of pigment-type gallstones within that classification.

Collection of local food samples

Due to the presence of both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems in the region, it serves as an ideal representation of various environmental conditions and human activities. From June to October 2023, a sampling activity was conducted over a period of 16 weeks, during which 500 commonly consumed food items were randomly selected from local popular markets. These items were categorized into six groups: condiments, grains, vegetables, fruits, seafood, and meat. Table 1 summarizes the methods for preparing samples from 243 food items that tested positive for Fe3+ and Cu2+, along with their respective categories, colors, and concentrations of Fe3+ and Cu2+. Other food items did not show detectable levels of Fe3+ or Cu2+.

Sample preparation

The pigment-type gallstones selected from the previous report were thoroughly washed with distilled water, followed by vacuum drying and grinding. The resulting powder was then sieved through a 100-mesh screen to obtain the final sample, which was subsequently sealed and stored in a storage cabinet. 500 food samples were cleaned of surface contaminants using distilled water. A stainless steel knife was utilized to cut the samples into smaller pieces for more efficient drying. These pieces were then placed in a freezer for 72 h. Following freezing, they were transferred to a tabletop freeze dryer, where they underwent vacuum drying at -65.5℃ for 48 h. Subsequently, the dried food samples were ground using a high-speed grinder. The resultant powder was further sieved through a 100-mesh screen and milled with quartz agate before being sealed and stored in a storage cabinet.

Content determination

Analysis of pigmented stones and food samples was conducted at room temperature, with 10 mg of powder from each sample being placed into an appropriate capillary tube for Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) measurements. The EPR spectra were measured using the A300 Electron Spin Resonance Spectrometer System (Bruker BioSpin GMBH, Germany) at an X-band frequency of 9.86 GHz. The g-factor was calculated using the relationship hν0 = gβH, where h represents Planck’s constant (h = 6.626 × 10–34 J·s), ν0 is the microwave frequency, β is the Bohr magneton (β = 9.262 × 10–24 J/T), and H is the magnetic field strength.

The EPR quantification was carried out on the standard sample of pigment gallstones that had been identified in the previously published articles16,17. The relevant quantitative auxiliary experiments by Ireneusz Stefaniuk18 and Kh. L. Gainutdinov19 were conducted at room temperature. The modulation amplitude, gain and microwave power of all experiments were selected under the condition that the EPR signal was not overmodulated or saturated. These parameters remained unchanged throughout all measurements. Before the measurement, the finished samples that were cut according to the shape of the measurement test tube were weighed. The weight of the samples was approximately 10 mg. The amplitude of the EPR spectrum was always normalized to the weight of the sample and the amplitude of the EPR signal of the reference sample.

As mentioned earlier16, the composition characteristics of pigment gallstones are studied based on the selective crystallization of polymorphic calcium carbonate, which all contain trace elements Fe and Cu. In this experiment, a series of CFC powders (Ca1 − xFex)CO3 (x = 0.0001–0.001) were prepared by solid-state reaction method using CaCO3 and Fe2O3 as raw materials at different temperatures and sintering times. By the above method, NCS powders (Ca1 − xCux)SO4 (x = 0.0001–0.001) were directly prepared using CaCO3 and CuSO4 as raw materials, which were non-magnetic. The concentrations of Fe3+ and Cu2+ in pigment gallstones were estimated by the intensity ratio of the simulated powders through EPR.

Results

EPR study of bile pigment stones

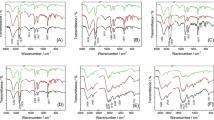

The analysis of representative pigment gallstones in powder form is illustrated in Fig. 1a. Given the possible presence of transition metal ions and bile pigment components within gallstones, we anticipate that both may generate Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) signals. Indeed, preliminary studies have indicated that pigment-type stones exhibit unique EPR spectral characteristics due to the free radical electrons and transition metal ions contained within them, as shown in Fig. 1b.

The EPR signal characteristic parameters for Fe(III) are g = 4.18 and ΔHpp = 4.85 mT, displaying an asymmetric high-spin spectrum. This finding aligns closely with Murugraj’s20 research, which noted that at room temperature, the signal from doped Fe3+ ions is more akin to oxygen vacancies, specifically g = 4.542; moreover, Fe3+ is present in most crystallites. For Cu(II), the EPR signal characteristic parameters are g‖= 2.36 and g⊥= 2.15. Notably, among samples exhibiting Cu(II) signals in gallstones, we also observed a multiplet hyperfine splitting spectrum near g⊥associated with four nitrogen ligands coordinated to Cu(II). Previous studies on crystalline solids containing Cu2+ ions revealed four perpendicular EPR signals alongside four parallel ones; this phenomenon features a broad envelope on the low-field side where hyperfine-coupled parallel components are embedded g values align well with experimental results. Similar spectra have been documented for materials doped with Cu2+, whether crystalline or glassy16,21.

In our investigation employing Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) on gallstone samples, significant signals related to transition metal ions were identified providing valuable insights into the composition and structure of these stones. The presence of Fe3+ in pigment gallstones primarily stems from gastrointestinal absorption of heme iron and non-heme iron12, while excessive intake of Fe3+ can lead to stone formation through hemolytic infections. The elevated levels of Cu2+ found in pigmented gallstones may be attributed to bilirubin’s influence since bilirubin imparts a black coloration to these stones. Copper is predominantly excreted endogenously via transport from the liver into bile; excess copper along with unabsorbed dietary copper exits the body through feces. Copper absorption and retention vary according to dietary intake levels and conditions20. High concentrations of copper can trigger acute gastrointestinal symptoms such as upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; however, specific concentrations leading to these symptoms remain unclear .

The content of Cu and Fe in food samples

In a study conducted on 500 food samples collected from popular markets in Jilin City, a total of 243 samples were found to contain trace elements Fe3+ and Cu2+. Representative samples were selected from various categories, including grains, condiments, fresh vegetables, meats, aquatic products, and fruits—resulting in the analysis of 12 distinct food items, At least five repeated measurements were conducted for each food sample, and the precision error of the measurements is shown in the figure. (Fig. 2). The content of iron and copper varied across different types of foods. The results indicated that the iron content in grain products was generally higher than that of copper; however, both remained relatively low at below 2 µg/g. In contrast, certain condiments such as pepper and Sichuan pepper exhibited iron and copper levels exceeding 2 µg/g, while other seasonings showed lower concentrations.

Analysis of the EPR spectra for vegetables revealed high levels of copper in green varieties such as lettuce, coriander, and leeks. Additionally, darker foods like black fungus demonstrated an iron content surpassing 10 µg/g. The EPR spectra for meat indicated that element concentrations were predominantly below 2 µg/g. Among fruits analyzed, only dragon fruit and oranges contained detectable amounts of iron and copper.

Discussion

The metal content in twelve categories of food is illustrated in Fig. 2. It can be observed that the copper concentration ranges from 0.77 to 18.81 µg/g, all of which are below the permissible limit of 50 mg/kg for copper. The iron content varies from 0 to 7.45 µg/g, also falling below the allowable limit of 50 mg/kg for iron. Meat, as a significant source of iron, is more readily absorbed during the formation of pigment gallstones. Martha Carolina Archundia-Herrera11 reported that the heme iron content in raw beef can reach up to 79%, and even after cooking, beef and lamb retain relatively high levels of heme iron. This suggests that the iron content in beef and lamb is generally higher compared to other meat products. Therefore, to accurately estimate iron intake, it is essential to consider the specific type of animal-based food and its cooking method, thereby providing a more reliable assessment of iron consumption.Notably, the metal concentrations in seasonings are generally higher than those found in other types of food, indicating a potential increase in metal contamination during the cultivation and processing stages of seasonings. Patients with gallstones should minimize their consumption of foods containing seasonings to reduce the risk of recurrence. Among vegetables, wood ear mushrooms exhibit significantly higher copper ion levels compared to other food types. Additionally, black rice shows slightly elevated metal concentrations relative to other varieties, suggesting that foods with darker pigmentation may contain marginally more copper than those with lighter colors.

From a dietary perspective, it appears that gallstone patients’ preference for foods rich in iron and copper along with certain condiments may be closely related to an increased risk factor for gallstone formation. Research indicates that high cholesterol intake may predispose individuals to gallbladder diseases; diets high in cholesterol have been shown to induce fatty bile and gallstones in experimental animals. Moreover, legumes containing substantial amounts of saponins have been found to enhance biliary cholesterol saturation while simultaneously reducing serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels; thus, a diet rich in legumes could potentially lower the incidence of stone formation22.

Ting Fang et al.23, through an analysis of trace metals concentration in Lake Chaohu water, discovered that bioaccumulated trace metals were more prevalent among high-nutrition organisms compared to others; shrimp were noted for their absorption rates of copper and zinc. The presence of trace metals within fish sourced from Lake Chaohu is unlikely to pose adverse effects due solely to lifelong fish consumption. Furthermore, some researchers have pointed out that Patagonian squid caught off the Atlantic coast might be exposed to elevated concentrations of copper due either naturally or anthropogenically derived sources due to its geographical location and habitat disruption affecting existing marine ecosystems24.

Conclusion

This experiment employs Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) technology to investigate the selected bilirubin stones and twelve types of food. The bilirubin stones exhibit a variety of appearances, resembling sandy shapes with sizes ranging from small to large, and are characterized by their reddish-brown or dark brown color, displaying a layered cross-section without a core. The concentrations of iron and copper elements in these stones are significantly higher than those of other trace elements. Given that the formation of pigment-type stones is closely related to pigments, analyzing the metal element concentrations in foods will play an important role in preventing bilirubin stone formation and patient care.

EPR signals for iron and copper were detected in both green vegetables and colored foods such as black rice and black fungus. Generally, seasonings have higher metal content compared to other food categories; therefore, it is recommended that affected patients minimize their consumption of these items. According to estimates based on hazard quotients (HQ), the non-carcinogenic risk appears lower than standardized values, indicating no adverse health effects for the general public from using these substances; however, there is a slightly elevated acceptable carcinogenic risk associated with chicken offal. Consuming chicken does not equate to exposure to heavy metals resulting in negative impacts. Nevertheless, the persistence of potentially toxic metals and their possible accumulation within animal tissues may contribute to the development of bilirubin stones25. Exposure to high levels of heavy metals has been linked with bilirubin stone formation; Ayobami O. et al.26, identified multiple trace metals with high THQ values in seasonings used for cooking in Nigeria—prolonged use could pose health risks for consumers.

Research indicates that urban areas engaged in heavy industrial activities tend to have elevated levels of heavy metals; thus, patients prone to stone formation should prioritize selecting foods produced away from industrialized regions. Consuming more products sourced from less polluted areas can significantly reduce potential heavy metal accumulation.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

03 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04744-4

References

Portincasa, P., Moschetta, A. & Palasciano, G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet 368 (9531), 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69044-2 (2006).

Cheng, Q. et al. Association of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) and gallstones among US adults aged = 50 years: A cross-sectional study from NHANES 2017–2020. Lipids Health Dis. 23 (1), 265. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02262-2 (2024).

Stewart, L., Oesterle, A. L., Erdan, I., Griffiss, J. M. & Way, L. W. Pathogenesis of pigment gallstones in Western societies: The central role of bacteria. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 6 (6), 891–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1091-255X(02)00035-5 (2002).

Brett, M. & Barker, D. J. P. The world distribution of gallstones, international. J. Epidemiol. 5 (4), 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/5.4.335 (1976).

Nilghaz, M. et al. Association between different dietary carbohydrates and risk of Gallstone: A case-control study in Iranian adults, nutrition. Food Sci. 54 (8), 1396–1404. https://doi.org/10.1108/nfs-12-2023-0299 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Recurrence of gallstones: A comprehensive multivariate analysis of clinical and biochemical risk factors in a large Chinese cohort of 16,763 patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1–9 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2024.2446626

Parviainen, A. et al. Combined microstructural and mineralogical phase characterization of gallstones in a patient-based study in SW Spain—Implications for environmental contamination in their formation. Sci. Total Environ. 573, 433–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.08.110 (2016).

Parviainen, A., Roman-Alpiste, M. J., Marchesi, C., Suarez-Grau, J. M. & Perez-Lopez, R. New insights into the metal partitioning in different microphases of human gallstones. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 44, 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2017.09.013 (2017).

Buch, S. et al. Loci from a genome-wide analysis of bilirubin levels are associated with gallstone risk and composition. Gastroenterology 139 (6), 1942–1951. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.003 (2010).

Pizarro, F., Olivares, M., Araya, M., Gidi, V. & Uauy, R. Gastrointestinal effects associated with soluble and insoluble copper in drinking water. Environ. Health Perspect. 109 (9), 949–952. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.01109949 (2001).

Archundia-Herrera, M. C. et al. Development of a database for the estimation of heme iron and nonheme iron content of animal-based foods. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 8 (4), 102130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdnut.2024.102130 (2024).

Di Ciaula, A. et al. The role of diet in the pathogenesis of cholesterol gallstones. Curr. Med. Chem. 26 (19), 3620–3638. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867324666170530080636 (2019).

Kruger, H. S., Balk, L. J., Viljoen, M. & Meyers, T. M. Positive association between dietary iron intake and iron status in HIV-infected children in Johannesburg, South Africa. Nutr. Res. 33 (1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2012.11.008 (2013).

Alharbi, W., Alharbi, K. H., Alotaibi, A. A., Gomaa, H. E. M. & Abdel Azeem, S. M. Digital image determination of copper in food and water after preconcentration and magnetic tip separation for in-cavity desorption/color development. Food Chem. 442, 138435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138435 (2024).

Iravani, S. & Soufi, G. J. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy: Food, biomedical and pharmaceutical analysis. biomedical. Spectrosc. Imaging. 9 (3–4), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.3233/bsi-200206 (2020).

Lu, D. Y. et al. Preliminary study on the correlation between the trace Mn(2+) and the calcite polymorph in gallstones containing calcium carbonate from the Northeast China via electron spin resonance. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 60, 126494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126494 (2020).

Lu, D. Y., Zhang, J., Liu, Q. L., Wang, H. G. & Cui, M. Different surface appearances caused by unbalanced Mn(2+) accumulation in gallstones consisting of cholesterol and CaCO(3) obtained from a patient after cholecystectomy. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 200 (6), 2660–2666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-021-02902-z (2022).

Stefaniuk, I., Obermayr, W., Popovych, V. D., Cieniek, B. & Rogalska, I. EPR spectra of sintered Cd(1-x)Cr(x)Te powdered crystals with various cr content. Materials (Basel) 14 (13), (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14133449

Gainutdinov, K. L. et al. Application of EPR spectroscopy to study the content of NO and copper in the frontal lobes, hippocampus, and liver of rats after cerebral ischemia. Tech. Phys. 67 (4), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1134/s106378422205005x (2022).

Rautray, T. R., Vijayan, V. & Panigrahi, S. Analysis of Indian pigment gallstones,nuclear instruments and methods. Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms. 255 (2), 409–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2006.12.147 (2007).

Kumar, B. V. & Vithal, M. Luminescence (M = Mn2+, Cu2+) and ESR (M = Gd3+, Mn2+, Cu2+) of Na2ZnP2O7. M Phys. B Condens. Matter. 407 (12), 2094–2099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2012.02.013 (2012).

Cuevas, A., Miquel, J. F., Reyes, M. S., Zanlungo, S. & Nervi, F. Diet as a risk factor for cholesterol gallstone disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 23 (3), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719360 (2004).

Fang, T. et al. Distribution, bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of trace metals in the food web of Chaohu lake, Anhui, China. Chemosphere 218, 1122–1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.107 (2019).

Traven, L. et al. Arsenic (As), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn) and selenium (Se) in Northwest Croatian seafood: A health risks assessment,toxicol rep 11, 413–419 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2023.10.012

Chijioke, N. O., Uddin Khandaker, M., Tikpangi, K. M. & Bradley, D. A. Metal uptake in chicken giblets and human health implications. J. Food Compos. Anal. 85, 103332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2019.103332 (2020).

Aigberua, A. O., Izah, S. C. & Isaac, I. U. Level and health risk assessment of heavy metals in selected seasonings and culinary condiments used in Nigeria. Biol. Evid. (2018). https://doi.org/10.5376/be.2018.08.0002

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiaxin Liu: Responsible for experimental validation, formal analysis, initial draft writing, review & editing, visualization, investigation, and data curation. Yan Liu and Qihui Shen: Involved in funding acquisition, conceptualization, methodology design, and research supervision. Hongyang Lv: Conducted the investigation and formal analysis. Weiao Li: Drafted the initial manuscript, performed validation, and provided resources. Litiao Ren: Handled data processing and participated in the investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: Hongyang Lv, Weiao Li and Litiao Ren were omitted from the author list in the original version of this Article. In addition, Yan Liu and Qi-Hui Shen were omitted as corresponding authors. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, JX., Liu, Y., Shen, QH. et al. Study on the correlation of electron spin resonance with pigment gallstones and trace Cu2+, Fe3+ in diet. Sci Rep 15, 8993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93870-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93870-0