Abstract

Lyme disease, caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, is transmitted to mammalian hosts during the feeding process of infected Ixodes ticks. Our previous studies demonstrated that the paralogous gene family 12 (PFam12) consisting of five members (BBK01, BBG01, BBH37, BBJ08, and BB0844) are non-specific DNA-binding proteins. PFam12 proteins share 31–69% sequence identity, are located either on the surface or within the periplasm and are upregulated as the tick starts its blood meal. The crystal structure of BBK01 revealed that the protein forms a homodimer, which is potentially critical for DNA binding. In this study, we determined the crystal structure of another PFam12 member, BBH37, to gain a better insight into this unique paralogous family. Although BBK01 dimerization is mediated by its C-terminal region and is thought to be critical for DNA binding, BBH37 forms dimers through an alternative mechanism where a unique disulfide bond is involved. We found that BBH37 is still able to interact with DNA with micromolar affinity. Molecular dynamics simulations and site-directed mutagenesis was conducted to characterize these unique DNA binding proteins. This study highlights the structural diversity within the PFam12, demonstrating that despite significant differences in dimerization mechanisms, these proteins retain their DNA-binding capability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lyme disease, caused by spirochetes of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex, includes species such as B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (hereafter B. burgdorferi), B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. spielmanii, B. mayonii, and B. bavariensis1,2,3. B. burgdorferi is transmitted to mammalian hosts through the bite of an infected Ixodes tick4,5. Lyme disease is a growing public health concern, with the number of cases increasing annually across Europe and the United States (cdc.gov and ecdc.europa.eu). The genome of B. burgdorferi strain B31 consists of a linear chromosome and twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNA elements (hereafter referred to as plasmids)6. Notably, the B. burgdorferi genome encodes at least 120 lipoproteins, which are covalently attached to the membrane lipid via an N-terminal lipid modification7. Approximately 70% of these lipoproteins are plasmid-encoded7. During the blood meal of an infected Ixodes tick, B. burgdorferi transitions from the tick midgut to the mammalian host by up-regulating the expression of several proteins, while down-regulating others8,9,10,11. The majority of proteins affected by regulation are lipoproteins, although the functions of many remain unknown6,9,12,13. Due to past recombination and duplication events, B. burgdorferi B31 harbors at least 160 paralogous gene families (PFams), and most lipoproteins have at least one paralog6. These paralogous genes, generated by extensive DNA rearrangements, are subject to random mutation events that may result in functional diversification. For example, in PFam54_60, only one of the 17 intact protein-coding genes, BBA68, is known to interact with the complement regulator Factor H14,15. Other members of this family have distinct roles: BBA64 is essential for the transfer of B. burgdorferi from the tick to the mammalian host16, while BBE31 is important for migration from the tick gut to the hemolymph17. Protein sequence analysis of PFam54_60 indicates that conserved residues primarily support proper folding, while surface residues tend to diverge, potentially facilitating functional diversification15,18,19. To expand our understanding of the largely uncharacterized Borrelia proteome, we recently investigated paralogous family 12 (PFam12), which consists of five members: BBK01, BBG01, BBH37, BBJ08, and BB0844 (also known as FtlA, FtlB, FtlC, FtlD and FtlE, respectively)20. PFam12 is particularly intriguing because its members are highly immunogenic, surface-localized lipoproteins (except BB0844, which resides in the periplasm) that tend to be up-regulated during the tick blood meal6,7,9,12,21,22,23,24. As previously uncharacterized lipoproteins potentially involved in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease, we studied the three-dimensional structure of BBK01 as the representative PFam12 member20. This revealed structural similarities to the structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) protein family, as well as the ability of all five PFam12 members to bind DNA nonspecifically. Despite low sequence similarity among PFam12 members (31–69%), sequence analysis indicated that conserved residues were not only essential for protein folding but also includes several lysine and arginine residues on the protein surface, potentially involved in DNA binding20. Given the significant structural differences observed between the crystal structure of BBK01 and its predicted AlphaFold model, we raised questions about the structural details of other PFam12 members20. In this study, we determined the crystal structure of PFam12 member BBH37, which, despite 53% sequence similarity to BBK01, revealed a distinct C-terminal conformation that significantly affected protein dimerization. In BBK01, the C-terminal region is involved in dimerization, forming the functional unit for DNA interaction. However, BBH37 formed a dimer through an entirely different mechanism, involving a unique disulfide bond. We determined the crystal structures of two BBH37 truncation variants (BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312) revealing variations in dimerization even within BBH37 itself. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provided further insights into the dynamic nature of the homodimers observed in the crystal structures of both BBH37 and BBK01, revealing surprising flexibility. Despite these structural differences and flexibility, our data confirmed that PFam12 proteins retain the ability to interact with DNA. This study provides new insights into the structural diversity within PFam12 and highlights the potential evolutionary adaptations of this protein family in B. burgdorferi. These findings contribute to our understanding of Borrelia pathogenesis and the diverse roles of lipoproteins in the lifecycle of this spirochete.

Results and discussion

Crystal structure of BBH37

The recombinant constructs for coding B. burgdorferi BBH37 were designed to exclude the signal sequence (residues 1–26) and the unstructured N-terminal region (residues 27–130), based on structural and sequence alignment data from a previous study on PFam12 proteins20 (Fig. 1A). The AlphaFold25 predicted model of BBH37, determined in this study, fully confirmed the expected locations of these regions (Fig. 1B). In the AlphaFold predicted model, the N-terminal region (residues 1–130) showed very low confidence, with an average predicted local-distance difference test (pLDDT) value of 39.6, indicating its highly flexible nature (Fig. 1C). Notably, the loop residues 124–130, located near the structural domain, had pLDDT values in the range of 70–80, suggesting generally accurate prediction. The flexible N-terminal region likely serves as a linker between the structural domain and the outer membrane. To increase the likelihood of obtaining protein crystals, and based on the location and confidence score of the unstructured region, we designed two constructs: one completely excluding the predicted loop region (BBH37131-312), and another incorporating its final portion, which had a relatively higher confidence score (BBH37119-312). . Previous studies have shown that the unstructured N-terminal region in PFam12 members does not affect DNA binding20. Plate-like crystals (Fig. 1D) of BBH37119-312 diffracted to 2.20 Å resolution in space group P21 with two molecules per asymmetric unit. The crystal structure was built for residues 123–311, as the initial few residues of the recombinant protein (residues 119–121) and the final residue were not built due to weak electron density. Needle-like crystals (Fig. 1D) of BBH37131-312 diffracted to 2.70 Å resolution in space group P212121, also with two molecules per asymmetric unit. The crystal structure was built for all residues except the final Ser312, though an additional glycine residue from the affinity tag was included at the N-terminus. The crystal structures of both recombinant proteins, BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312, produced highly similar overall folds, with Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 1.77 Å, forming an all α-helical protein composed of five α-helices (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, the crystal structure of BBH37 showed high overall similarity to the AlphaFold predicted model, with an RMSD of 1.53 Å (Fig. 1F).

Structural analysis of BBH37. (A) Schematic illustration of BBH37 showing the locations of the signal sequence, unstructured region and structural domain. (B) AlphaFold predicted model of full-length BBH37 with the signal sequence region (blue), unstructured region (yellow), and structural domain (brown) highlighted. (C) AlphaFold predicted model of BBH37, colored according to pLDDT confidence values, ranging from red (low confidence) to white (high confidence). (D) Plate-like crystals of BBH37119-312 (left) and needle-like crystals of BBH37131-312 (right). (E) Crystal structure of BBH37119-312 (blue) superimposed with BBH37131-312 (gold). (F) Crystal structure of BBH37119-312 (blue) superimposed with the AlphaFold predicted model (brown). All five α-helices from the structural domain are indicated (αA-αE).

Crystal structures of BBH37 and BBK01 as PFam12 members

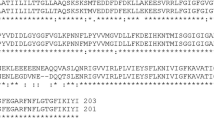

The crystal structure of BBK01 (PDB ID 8CQN) previously determined at 2.7 Å resolution, unexpectedly showed notable differences compared to its high-confidence AlphaFold predicted model (pLDDT value of 93.9 for structural domain residues 112–297)20. In the crystal structure, the αC helix formed a continuous α-helix, whereas in the AlphaFold model, this region was split into two antiparallel α-helices (Fig. 2A). To compensate for the hydrophobic path formed by αA, αB, and the N-terminal portion of αC, BBK01 adopts a homodimeric conformation. In this dimer, the extended α-helix occupies the position corresponding to αD in the AlphaFold model (Fig. 2B). For BBH37, AlphaFold predicted the same high-confidence fold (pLDDT value of 93.6 for structural domain residues 131–312) as for BBK01, with a discontinuous αC (Fig. 1B). To validate these predictions, the experimental structure of BBH37 was determined. In contrast to BBK01, the crystal structure of BBH37 matched the AlphaFold predicted model, confirming the discontinuous α-helix (Fig. 1F). Despite the differences in the C-terminal α-helix between BBH37 and BBK01, the remaining structural domain was highly similar, with an RMSD of 1.94 Å (Fig. 2C). For other PFam12 members (BBG01, BBJ08, and BB0844), AlphaFold predicted that the C-terminal α-helix is discontinuous, consistent with the BBH37 crystal structure (Fig. 2C). Based on amino acid sequence alignment across PFam12 members, the region determining whether the C-terminal α-helix bends backward or forms a continuous helix is conserved, except in BBH37 and BB0844. This suggests that BBK01, along with BBG01 and BBJ08, likely adopts an extended C-terminal α-helix, whereas BBH37 and BB0844 feature a discontinuous α-helix (Fig. 2D). Analysis using the DALI server26 showed that BBK01, mainly due to its extended C-terminal α-helix, is structurally similar to members of the structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) protein family20. SMC proteins are multidomain proteins involved in chromosome organization and dynamics. In BBK01, the similarity is limited to the central coiled-coil region of SMC proteins, which is not associated with DNA binding20. However, for BBH37, DALI analysis indicated the highest similarity to a haemoglobin receptor from Trypanosoma congolense, which provides the bacteria with a source of heme (Fig. S1)27. Given that both proteins show only 15% sequence similarity, it is unlikely that these proteins share functional similarity.

Structural analysis of PFam12 members BBH37 and BBK01. (A) Crystal structure of BBK01 (PDB ID 8CQN; green) superimposed with the AlphaFold predicted model (gray). The α-helices in the crystal structure (αA-αC) and the predicted model (αD) are indicated. (B) Homodimer of BBK01, with protomers illustrated in light green and dark green, superimposed with the AlphaFold predicted model (gray). (C) Crystal structure of BBH37119-312 (blue) superimposed with the crystal structure of BBK01110-297 (green; RMSD 1.94 Å), and the AlphaFold predicted structural domains of BBG01110-297 (pink; RMSD 1.80 Å), BBJ08126-306 (yellow; RMSD 2.60 Å), and BB084495-323 (brown; RMSD 2.49 Å). (D) Sequence alignment of structural domains for PFam12 members, highlighting conserved residues in red and conserved substitutions in yellow. The region in BBH37, BBG01, BBJ08, and BB0844 where a reversal of the α-helix is observed relative to BBK01 is squared in the alignment. The residues forming the loop region are indicated. Residues involved in BBH37131-312 homodimer formation are indicated with an asterisk (*). The numbering above the alignment corresponds to BBH37.

Dimerization of BBH37 and its comparison with the BBK01 dimer

The dimerization of BBK01 has been proposed to play a role in DNA binding by forming a potential DNA binding site at the central part of the dimer, where conserved lysine and arginine residues of PFam12 are located. Since all PFam12 members have been shown to be non-specific DNA binding proteins, the question arises whether BBH37 is also capable of forming a dimer and how this might affect DNA binding. The crystal structures of both recombinant BBH37 proteins, BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312, which crystallized in two different forms, revealed that the protein forms a homodimer. However, these dimers are slightly different between the two recombinant proteins and are distinct from that observed for BBK01 (Figs. 2B, 3A, and 3B). The protomers in the homodimers of BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312 are covalently linked by a disulfide bond between surface-exposed Cys165 residues (Figs. 3A and 3B). Although the protomers in both crystal forms are nearly identical (RMSD 1.77 Å) (Fig. 1E), the dimerization differs. In BBH37119-312, one protomer is rotated by 180° relative to the other, while both protomers remain linked by the disulfide bond (Figs. 3A and 3B). Although the electron density shows a convincing interaction between the Cys165 residues in both protomers in BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312 (Figs. 3C and 3D), we performed reduced versus non-reduced SDS-PAGE to confirm the presence of this disulfide bond. In the presence of Laemmli SDS sample buffer containing the reducing agent β-mercaptoethanol, BBH37 appeared as a monomeric protein (21 kDa). Without the reducing agent, the protein matched double the size, indicating dimerization under these conditions (Fig. 3E). These results confirm that BBH37 forms a disulfide bond between protomers in the crystallization solutions (0.01 M manganese(II) chloride, 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.6) and 2.5 M 1,6-hexanediol or 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.6), 20% 2-propanol and 20% PEG 4000) or sample buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 50 mM sodium chloride). To analyze the role of the disulfide bond in dimer formation, recombinant mutant proteins BBH37131-312 Cys165Ala and BBH37131-312 Cys165Ser were produced. Gel-filtration chromatography showed no significant differences in the elution volumes of BBH37119-312, BBH37131-312, and the mutant proteins, indicating that the oligomerization state remained consistent (Fig. 4). This suggests that Cys165 is not playing a major role for dimer formation or stability. Indeed, PISA assembly analysis showed that BBH37131-312 forms a homodimer with a buried surface area of 3420 Å2 (compared to 7950 Å2 for the BBK01 homodimer; Fig. 2B)28, primarily through ionic interactions (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, only three of approximately 20 residues involved in dimerization are conservative among PFam12 members, while 10 are conserved substitutions (Fig. 2D). The unique presence of Cys165 in BBH37 suggests that this dimerization pattern may be exclusive to BBH37. In contrast, the BBH37₁₁₉₋₃₁₂ homodimer, with a buried surface area of 1850 Å2 as determined by PISA assembly analysis, is stabilized predominantly by hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 3B).

Homodimerization of BBH37. (A) Homodimer of BBH37131-312 (gold and gray). (B) Homodimer of BBH37119-312 (blue and gray). All five α-helices from the structural domain are indicated (αA-αE). The 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 1 σ, showing the disulfide bond region between (C) Cys165 protomers in BBH37131-312 and (D) BBH37119-312. (E) SDS-PAGE analysis of BBH37131-312 under reduced and non-reduced conditions.

Molecular dynamics simulations of BBH37 homodimers

Considering that three dimerization patterns observed within PFam12, and taking into account that we have the crystal structures for BBK01110-297, BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312 in hand, MD simulations were conducted to examine the dynamic nature of these homodimers. For BBH37119-312 homodimer, 100 ns MD simulations revealed significant structural variations, with RMSD values, presenting dynamic changes in the protein structure over time, ranging from 20 to 70 Å after three simulations (Fig. 5A and Suppl. Movie 1). Despite this, the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values, presenting the local residue fluctuations in the protein structure during MD simulation, were relatively low, with most residues fluctuating within the 7–18 Å range (Fig. 5B). Higher RMSF values were observed in loop regions, such as residues 190–200 (between αB and αC) and 250–260 (between αD and αE) (Figs. 3A and 5B). Structural alignment of the crystal structure of BBH37119-312 homodimer and the MD output structures revealed marked rotational motion between the protomers (Fig. 5C and Suppl. Movie 2). In contrast, the BBH37131-312 homodimer revealed minor motion between protomers, with RMSD values in the 20–30 Å range (Fig. 5D and Suppl. Movie 3). RMSF values were similarly low, fluctuating around 10 Å, with slightly elevated values in loop regions (Fig. 5E). The superimposed structures of BBH37131-312 with the MD output structure revealed minimal protomer movement (Fig. 5F and Suppl. Movie 4). For the BBK01110-297 homodimer, RMSD value was in the 20–80 Å range (Fig. 5G and Suppl. Movie 5), with RMSF values in the 10–25 Å range (Fig. 5H). Increased RMSF value was observed for residues 170–180 corresponding to the loop region between αB and αC (Fig. 2A). Superimposed crystal structure of BBK01110-297 with the MD structure showed minor up-and-down protomer motions (Fig. 5I and Suppl. Movie 6). Overall, RMSD and RMSF measurements suggest that BBH37119-312 and BBK01110-297 homodimer inherits greater flexibility, while BBH37131-312 dimer appears more rigid. It is important to note that the residues responsible for the extended version of the C-terminal α-helix, as seen in BBK01, or the inverted version, as observed in BBH37 (Fig. 2C), do not show increased flexibility. Backbone measurements for individual chains confirm the robustness of the BBH37131-312 dimer, while the higher RMSD for BBH37119-312 results from contributions by both chains (Fig. S2).

RMSD values from MD simulations plotted as a function of time for (A) BBH37119-312 homodimer (D) BBH37131-312 homodimer and (G) BBK01110-297 homodimer. Cα atom RMSF values derived from MD simulations for individual protomers for (B) BBH37119-312, (E) BBH37131-312 and (H) BBK01110-297 plotted by residue number. Different colours (black, green, red) represent three independent runs. Structural alignment of the output structure from the MD simulations with the crystal structure of (C) BBH37119-312 homodimer, (F) BBH37131-312 and (I) BBK01110-297.

DNA binding by BBH37

Based on ITC experiments, the binding affinity of BBK01 to various DNA fragments was estimated, with Kd values ranging from 0.10 to 1.42 μM for 36 bp and 24 bp DNA fragments, respectively. The stoichiometry obtained from titration experiments suggested that multiple protein molecules can interact with a single DNA molecule20. This observation is consistent with the finding that PFam12 members are non-specific DNA-binding proteins, allowing several protein molecules to simultaneously bind to a DNA molecule. In this study, ITC experiments conducted for the BBH37 protein determined a Kd value of 5.6 μM using a 36 bp DNA fragment (Table S1; Fig. S3). While site-directed mutagenesis has been used to identify DNA-binding residues in BBK01, revealing that all PFam12 members are non-specific DNA binding proteins20, the different mode of dimerization observed in BBH37 prompts a re-evaluation of the residues involved in its DNA binding. The DNA binding site in BBK01 was proposed to be located at the central region of the dimer, where conserved lysine and arginine residues cluster. This cluster creates a central cleft with a distinct positive charge (Fig. 6A)20. In contrast, BBH37 shows a distinct positive charge near the terminal ends of the homodimer (Figs. 6B,C). While conserved residues in PFam12 members are relatively evenly spaced in BBH37, positively charged lysine and arginine residues tend to localize at the distal ends of the homodimer (Figs. 6D,E). To identify the specific residues in BBH37 involved in DNA binding, ten single mutants and four double mutants were generated using site-directed mutagenesis. To confirm that these mutant proteins retain the same fold as the wild-type protein, CD spectroscopy was performed on both the wild-type BBH37 and the mutants. The results revealed that all proteins shared similar CD spectra, characteristic of an α-helical secondary structure (Fig. S4). For the mutagenesis studies, alanine substitutions were focused on surface-exposed lysine and arginine residues, some of which are conserved among PFam12 members. Additionally, one glutamine and one asparagine residue were selected for mutagenesis (Figs. 6D,E). Using agarose gel electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSA), it was determined that mutations in residues Arg200, Arg204, Arg254, and Arg261 to alanine negatively impacted DNA binding (Fig. 7). These residues, identified as key for DNA binding in BBH37, are located near the terminal ends of the homodimer (Fig. 8). In BBK01, the residues Arg180, Lys182, Lys234, Arg235, and Arg242 were previously identified as important for DNA binding20. Notably, Arg180 and Lys182 in BBK01 correspond to Arg200 and Arg204 in BBH37, while Arg235 and Arg242 in BBK01 align with Arg254 and Arg261 in BBH37 (Fig. 8). In BBK01, analysis of several double mutants revealed that the Arg242Ala + Arg180Ala mutation resulted in a complete loss of DNA binding. Similarly, in BBH37, the corresponding double mutant Arg200Ala + Arg261Ala showed one of the most pronounced negative effects on DNA binding among all the BBH37 mutants analyzed.These findings indicate that, despite differences in dimerization modes, the residues involved in DNA binding are conserved. In conclusion, mutagenesis studies and the distinct positive electrostatic potential observed in BBH37 suggest that its DNA-binding site is located at the distal ends of the homodimer (Fig. 6A–C). This highlights a conserved mechanism of DNA interaction within PFam12 proteins, albeit with structural adaptations to their specific modes of dimerization.

Electrostatic surface potential of B. burgdorferi (A) BBK01110-297 (PDB ID 8CQN), (B) BBH37119-312, and (C) BBH37131-312. The electrostatic potentials (red, negative; blue, positive) were calculated using APBS29. Surface contour levels were set to -1 kT/e (red) and + 1 kT/e (blue). Residues conserved between PFam12 members illustrated as bond models in (D) BBH37119-312 and (E) BBH37131-312. The residues targeted for site-directed mutagenesis are circled.

Our study provides significant insights into the structural and functional diversity of the PFam12 protein family in Borrelia burgdorferi, a critical factor in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease. Despite sharing moderate sequence similarity, PFam12 members exhibit distinct structural features, particularly in their dimerization mechanisms. For example, the BBH37 protein forms a dimer through a unique disulfide bond, in contrast to BBK01, where the C-terminal region mediates dimerization. The ability of PFam12 proteins to bind DNA nonspecifically is preserved despite their structural variability, suggesting a conserved functional role across the family. Our findings highlight key residues, including conserved lysine and arginine residues on the protein surface, which may contribute to DNA-binding capabilities. Molecular dynamics simulations further revealed the inherent flexibility of PFam12 homodimers, which could play a role in their interaction with DNA and potentially other macromolecules. These results expand our understanding of the B. burgdorferi proteome and underscore the importance of studying paralogous protein families to uncover their distinct and shared roles. The structural and functional diversity observed within PFam12 exemplifies the evolutionary adaptations of Borrelia lipoproteins, likely facilitating their roles in the pathogen’s complex lifecycle and host interactions. Further studies are needed to elucidate the biological relevance of PFam12 proteins during infection and their potential as targets for therapeutic intervention.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of BBH37

Recombinant BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312 (UniProtKB: O50692), lacking the N-terminal signal sequence and the following unstructured region, were produced by amplifying the corresponding gene via PCR from the genomic DNA of B. burgdorferi B31. The primers used are listed in Table S1. The PCR fragment was ligated into the pETm-11 expression vector, which encodes an N-terminal 6xHis tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site. Expression and purification of BBH37 were performed as previously described20. The same procedure was followed for producing and purifying BBH37 mutant proteins, including BBH37C165A, BBH37C165S, BBH37R200A, BBH37R200A+R254A, BBH37R200A+R261A, BBH37K202A, BBH37R204A, BBH37R204A+R254A, BBH37R204A+R261A, BBH37Q208A, BBH37N212A, BBH37K248A, BBH37K253A, BBH37R254A, BBH37R261A, and BBH37R294A.

Crystallization, data collection, and structure determination

BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312 were crystallized in 96-well plates by mixing 0.4 μl of protein (8 mg/ml) with 0.4 μl of precipitant solution from JCSG-plus or Structure Screen 1 and 2 sparse matrix screens (Molecular Dimensions), using a Tecan Freedom EVO100 workstation (Tecan Group). Thin, plate-like crystals of BBH37119-312 were obtained with a solution containing 0.01 M manganese(II) chloride, 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.6), and 2.5 M 1,6-hexanediol. Needle-like crystals of BBH37131-312 formed in a solution of 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.6), 20% 2-propanol, and 20% PEG 4000 after several weeks. Crystals of BBH37119-312 selected for data collection were frozen in liquid nitrogen without cryoprotection, whereas 15% glycerol was used as a cryprotectant for BBH37131-312. Diffraction data for BBH37119-312 were collected at the Diamond Light Source (Oxfordshire, UK) beamline I03, and for BBH37131-312 at the BioMAX beamline of the MAX IV Laboratory (Lund, Sweden). Reflections were indexed and scaled using iMOSFLM and AIMLESS from the CCP4 suite30,31. Initial phases were obtained by molecular replacement with Phaser, followed by model building in BUCCANEER32,33, using the crystal structure of the paralogous protein BBK01 (PDB ID 8CQN) as a search model. Manual model improvement was performed in COOT34, and crystal structure refinement was performed using REFMAC535. Data collection, refinement, and validation statistics for BBH37 are summarized in Table S2.

Structure prediction using AlphaFold

AlphaFold v2.025 was used to predict the 3D structure for BBH37. Predictions were performed with default parameters as described on AlphaFold GitHub repository, using an AMD Ryzen Threadripper 2990 WX 32-Core system with 128 GB RAM and four NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 GPUs. Databases were downloaded on March 25, 2024. For further analysis, the predicted structure with the highest confidence (based on pLDDT scores) was used.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using pETm-11-BBH37131-312 as a template to generate BBH37 mutants, including BBH37C165A, BBH37C165S, BBH37R200A, BBH37R200A+R254A, BBH37R200A+R261A, BBH37K202A, BBH37R204A, BBH37R204A+R254A, BBH37R204A+R261A, BBH37Q208A, BBH37N212A, BBH37K248A, BBH37K253A, BBH37R254A, BBH37R261A, and BBH37R294A. PCR was performed with mutation-specific complementary primers (Table S1). PCR products were treated with endonuclease DpnI to digest methylated parental DNA and transformed into E. coli XL1-blue cells. Colonies grown on LB agar plates with kanamycin were transferred to LB medium with kanamycin and grown overnight at 37 °C. Plasmid DNA was isolated and sequenced to confirm mutations (Fig. S5).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

The EMSA experiment was performed as previously described for PFam12 proteins20. A PCR-amplified DNA fragment (1938 bp) of the B. burgdorferi B31 bb0236 gene was used. Proteins were diluted to equal final concentrations, and five different dilutions were prepared, yielding DNA–protein molar ratios ranging from 1:180 to 1:2888.

Gel filtration chromatography

To determine and compare the oligomerization state, 100 μl of protein (3 mg/ml) in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 100 mM sodium chloride was loaded onto a Superdex 200 Increase 10/30 column (Cytiva, MA, USA) connected to ÄKTA pure chromatography system (Cytiva, MA, USA). The flow rate was set to 0.5 ml/min, with the column equilibrated in the same buffer.

MD simulations

All-atom molecular dynamics simulations of BBK01110-297, BBH37119-312, and BBH37131-312 (PDB IDs 8CQN, 8S2P, and 8S2F) were performed using GROMACS 2021 on an high performance computing center at Riga Technical University with the CHARMM36 forcefield (July 2022 version). Simulations for protein homodimers as observed in the crystal structures were run at physiological salt concentrations (150 mM NaCl) and 300 K. Energy minimization was achieved in ≤ 100 000 steps. Leap-frog algorithm with 2 fs time step was used for motion equation integration. Systems were equilibrated by generating an NVT ensemble for 100 ps (with V-rescale thermostat), followed by 100 ps NPT ensemble run (Berendsen barostat, 1 bar reference pressure). During equilibration backbone atoms were restrained with force constant of 1000 kJ mol-1 nm-2. Production runs for protein dimers were conducted for 100 ns. TIP3P water model was selected for all systems. Electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald algorithm with a real-space cutoff of 1.2 nm. Van der Waals interactions were cut off at 1.2 nm, switching potential after 1.0 nm. Covalent bonds with hydrogen atoms were restrained with LINCS algorithm. Production runs were performed with V-rescale algorithm for thermostat and isotropic pressure coupling with Parinello-Rahman barostat (reference pressure – 1 bar).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were performed using a MicroCal™ iTC200 instrument (Malvern Panalytical) as described previously for PFam12 member BBK0120. All titrations were performed at 25 °C. Protein solution (70–120 μM) was titrated with dsDNA fragments (36 bp; Table S1) at 35–50 μM, depending on the protein concentration.

Circular dichroism

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements for wild-type and mutant proteins were performed on a Jasco J-1500 spectropolarimeter (Jasco). The experiment was conducted as described previously20. Briefly, spectra of 5 μM protein samples in 15 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM sodium chloride, and 10 mM monosodium phosphate were recorded in continuous scanning mode (200–250 nm) at 20 °C using a 2.0 mm pathlength quartz cuvette.

Sequence analysis

Sequence alignment of PFam12 members was performed using Clustal Omega and manually adjusted based on 3D structural comparisons (BBK01, BBH37 crystal structures, and AlphaFold models of BBG01, BBJ08, and BB0844). Alignments were visualized using ESPript 336,37.

Data availability

The coordinates and structure factors for BBH37119-312 and BBH37131-312 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 8S2P and 8S2F, respectively. Sequencing data for BBH37 mutants is included in the supplementary information.

References

Rudenko, N., Golovchenko, M., Grubhoffer, L. & Oliver, J. H. Jr. Updates on Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex with respect to public health. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2, 123–128 (2011).

Stanek, G. & Reiter, M. The expanding Lyme Borrelia complex–clinical significance of genomic species?. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 487–493 (2011).

Pritt, B. S. et al. Borrelia mayonii sp. Nov., a member of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex, detected in patients and ticks in the upper midwestern United States. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66, 4878–4880 (2016).

Burgdorfer, W. et al. Lyme disease-a tick-borne spirochetosis?. Science 216, 1317–1319 (1982).

Steere, A. C. et al. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308, 733–740 (1983).

Casjens, S. et al. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 490–516 (2000).

Dowdell, A. S. et al. Comprehensive spatial analysis of the Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteome reveals a compartmentalization bias toward the bacterial surface. J. Bacteriol. 199, e00658-16 (2017).

Kenedy, M. R., Lenhart, T. R. & Akins, D. R. The role of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface proteins. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 66, 1–19 (2012).

Ojaimi, C. et al. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect. Immun. 71, 1689–1705 (2003).

Samuels, D. S. et al. Gene regulation and transcriptomics. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 42, 223–266 (2021).

Stevenson, B. The Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, as a model vector-borne pathogen: insights on regulation of gene and protein expression. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 74, 102332 (2023).

Brooks, C. S., Hefty, P. S., Jolliff, S. E. & Akins, D. R. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect. Immun. 71, 3371–3383 (2003).

Tokarz, R., Anderton, J. M., Katona, L. I. & Benach, J. L. Combined effects of blood and temperature shift on Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression as determined by whole genome DNA array. Infect. Immun. 72, 5419–5432 (2004).

Kraiczy, P. et al. Complement resistance of Borrelia burgdorferi correlates with the expression of BbCRASP-1, a novel linear plasmid-encoded surface protein that interacts with human factor H and FHL-1 and is unrelated to Erp proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2421–2429 (2004).

Brangulis, K., Akopjana, I., Petrovskis, I., Kazaks, A. & Tars, K. Structural analysis of the outer surface proteins from Borrelia burgdorferi paralogous gene family 54 that are thought to be the key players in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease. J. Struct. Biol. 210, 107490 (2020).

Gilmore, R. D. Jr. et al. The bba64 gene of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent, is critical for mammalian infection via tick bite transmission. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A 107, 7515–7520 (2010).

Zhang, L. et al. Molecular interactions that enable movement of the Lyme disease agent from the tick gut into the hemolymph. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002079 (2011).

Brangulis, K., Petrovskis, I., Kazaks, A., Baumanis, V. & Tars, K. Structural characterization of the Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein BBA73 implicates dimerization as a functional mechanism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 434, 848–853 (2013).

Brangulis, K. et al. Structure of an outer surface lipoprotein BBA64 from the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi which is critical to ensure infection after a tick bite. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 69, 1099–1107 (2013).

Brangulis, K. et al. Members of the paralogous gene family 12 from the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi are non-specific DNA-binding proteins. PLoS ONE 19, e0296127 (2024).

Barbour, A. G. et al. A genome-wide proteome array reveals a limited set of immunogens in natural infections of humans and white-footed mice with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 76, 3374–3389 (2008).

Revel, A. T., Talaat, A. M. & Norgard, M. V. DNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 99, 1562–1567 (2002).

Carroll, J. A., Cordova, R. M. & Garon, C. F. Identification of 11 pH-regulated genes in Borrelia burgdorferi localizing to linear plasmids. Infect. Immun. 68, 6677–6684 (2000).

Camire, A. C. et al. FtlA and FtlB are candidates for inclusion in a next-generation multiantigen subunit vaccine for lyme disease. Infect. Immun. 90, e0036422 (2022).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Holm, L. DALI and the persistence of protein shape. Protein Sci. 29, 128–140 (2020).

Lane-Serff, H. et al. Evolutionary diversification of the trypanosome haptoglobin-haemoglobin receptor from an ancestral haemoglobin receptor. Elife 5, e13044 (2016).

Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007).

Jurrus, E. et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein Sci. 27, 112–128 (2018).

Winn, M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 235–242 (2011).

Battye, T. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 271–281 (2011).

Cowtan, K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 1002–1011 (2006).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 (1997).

Sievers, F. et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 (2011).

Robert, X. & Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 (2014).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Latvian Council of Science fundamental and applied research project Nr. lzp-2021/1-0068 (for K.B.). We acknowledge MAX IV Laboratory (Lund, Sweden) for time on BioMAX beamline under proposal 20220773. Research conducted at MAX IV, a Swedish national user facility, is supported by the Swedish Research council under contract 2018-07152, the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems under contract 2018-04969, and Formas under contract 2019-02496. We would like to thank Diamond Light Source (Oxfordshire, UK) for beamline (proposal mx35587), and the staff of beamline I03 for assistance with crystal testing and data collection. We thank Shapla Bhattacharya from Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis for assistance with CD measurements.

Funding

Latvijas Zinātnes Padome,lzp-2021/1-0068,lzp-2021/1-0068,lzp-2021/1-0068

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kalvis Brangulis: conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing. Dagnija Tupina: investigation. Everita Elina Sinicina: investigation. Diana Zelencova-Gopejenko: investigation. Inara Akopjana: investigation. Janis Bogans: investigation. Kaspars Tars: writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 1.

Supplementary Video 2.

Supplementary Video 3.

Supplementary Video 4.

Supplementary Video 5.

Supplementary Video 6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brangulis, K., Tupina, D., Sinicina, E.E. et al. Divergent dimerization mechanisms and conserved DNA-binding function in PFam12 proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Sci Rep 15, 11518 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93944-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93944-z