Abstract

The application of intelligent technology to enhance decision-making, optimize processes, and boost project economics and sustainability has the potential to significantly revolutionize the construction industry. However, there are several barriers to its use in small-scale construction projects in China. This study aims to identify these challenges and provide solutions. Using a mixed-methods approach that incorporates quantitative analysis, structural equation modeling, and a comprehensive literature review, the study highlights key problems. These include specialized challenges, difficulty with data integration, financial and cultural constraints, privacy and ethical issues, limited data accessibility, and problems with scalability and connection. The findings demonstrate how important it is to get rid of these barriers to fully utilize intelligent computing in the construction sector. There are recommendations and practical strategies provided to help industry participants get over these challenges. Although the study’s geographical emphasis and cross-sectional approach are limitations, they also offer opportunities for further investigation. This study contributes significantly to the growing body of knowledge on intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects and offers practical guidance on how businesses might leverage their transformative potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intelligent computing has the potential to revolutionize the construction industry by improving decision-making, streamlining processes, and enhancing project outcomes1. Intelligent computing refers to the use of advanced computational techniques, including artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), big data analytics, and automation, to create adaptive and efficient systems capable of solving complex problems and optimizing various processes. These technologies enable predictive analytics, automated decision-making, and real-time monitoring, significantly enhancing productivity and sustainability in construction projects. However, its implementation in small-scale construction projects presents several challenges that must be addressed. These challenges stem from the specific nature of smaller projects, such as limited resources, budgets, and project durations, making the upfront costs of adopting intelligent computing technologies difficult to manage2. Small-scale construction projects are a significant part of the construction sector, especially in countries like the United States, where approximately 99% of the industry consists of small businesses3. These projects are often constrained by financial, human, and time resources. As a result, the adoption of intelligent computing technologies, which require substantial investment in both equipment and expertise, can be a daunting task4. Despite the promise of improved decision-making and enhanced project outcomes, the cost and complexity of implementation are often seen as prohibitive. Data management is another critical challenge for small-scale projects5. While construction projects generate vast amounts of data, the management and use of this data for intelligent computing are often suboptimal6. Issues such as inconsistent data collection methods, insufficient data sources, and short project durations can hinder the availability of high-quality data necessary for these systems to function effectively7. Research indicates that between 30% and 40% of construction projects suffer from data quality problems, which can undermine the effectiveness of decision-making models based on this data8.

In addition to data issues, the technical expertise required to deploy intelligent computing is another barrier for small-scale construction projects9. A survey of industry professionals reveals that approximately 70% of construction organizations report difficulty finding employees with the necessary skills in machine learning and artificial intelligence10. Small projects may lack the budget to hire or train specialized personnel, further complicating the adoption of intelligent computing11. Cultural factors, such as resistance to change, also pose significant challenges. According to a survey conducted by a construction research institute, around 60% of construction experts believe that resistance to new technologies is a major obstacle to the successful deployment of intelligent computing12. Small-scale projects often face greater cultural resistance, making it more difficult to implement innovative solutions. Overcoming these cultural barriers and fostering an environment conducive to change are crucial for the effective integration of intelligent computing13. The complexity of integrating various software tools and systems into small-scale projects further exacerbates these challenges14. Research suggests that more than 40% of construction organizations require help with integrating different technologies15. This problem is particularly pronounced in small projects, where limited technical expertise and funding make it difficult to ensure seamless integration16. Without proper integration, the full benefits of intelligent computing cannot be realized. Addressing these challenges requires a deeper understanding of the specific issues faced by small-scale construction projects17. Tailored solutions that consider the unique constraints of these projects are necessary to overcome these obstacles18. Successfully addressing these challenges will allow small-scale construction projects to harness the potential of intelligent computing, improving decision-making, productivity, and overall project performance19. This study fills an important gap in existing literature by examining the challenges of implementing intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects. It also contributes to the field by using structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore the complex relationships between these challenges and how they affect the adoption of intelligent computing. While previous research has focused on broader, more generic challenges, this study provides a more detailed, context-specific analysis, particularly for small-scale projects, especially in China. The study uses SEM to examine the interconnections between economic, cultural, technical, and data-related barriers to intelligent computing adoption. SEM provides a systematic approach to understanding how these factors interact and influence the successful use of intelligent computing technologies in small-scale construction projects. The analysis offers valuable insights into the fundamental obstacles faced by small enterprises in the construction sector and proposes strategies for overcoming them. One of the study’s key contributions is its focus on context-specific challenges, which have received limited attention in prior research. By focusing on small-scale projects in China, this study provides new perspectives on the difficulties faced by these projects when integrating intelligent computing technologies. The findings offer practical solutions for overcoming the barriers to adoption, such as leveraging modular tools, adopting cloud-based systems, and improving data quality standards.

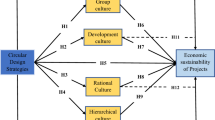

The hypothesis developed as shown in Fig. 1 in this study visualizes the key barriers and their interrelationships, providing a clear understanding of the challenges involved in adopting intelligent computing. This hypothesis development serves as a foundation for the subsequent analyses and offers a roadmap for addressing the complex factors that hinder the successful integration of intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects. This study advances theoretical knowledge on the adoption of intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects while offering practical recommendations for overcoming the barriers to implementation. By focusing on the specific challenges faced by small enterprises, particularly in the context of China, this research contributes to the development of a more nuanced understanding of how intelligent computing can be successfully integrated into the construction sector. The study’s findings provide valuable insights for industry stakeholders seeking to improve project efficiency, decision-making, and overall outcomes.

H1: Complexity and customization barriers are significantly related to implementing intelligent computing in small construction projects.

H2: Data quality and integration customization barriers significantly relate to implementing intelligent computing in small construction projects.

H3: Economic and culture customization barriers significantly relate to implementing intelligent computing in small construction projects.

H4: Ethical and privacy customization barriers significantly relate to implementing intelligent computing in small construction projects.

H5: Limited and data availability customization barriers are significantly related to implementing intelligent computing in small construction projects.

H6: Scalability and integration customization barriers are significantly related to implementing intelligent computing in small construction projects.

Literature review

The construction industry is characterized by the vast amount of data it generates throughout the project lifecycle20. From project planning to execution and completion, data is produced at every stage, often stored across various devices such as team servers, desktop computers, laptops, and mobile phones21. This scattered data storage system makes it difficult to access a comprehensive view of the data, leading to poor decision-making that can hinder project progress and negatively impact performance and profitability22. Traditionally, information and communication technology (ICT) in the construction industry has relied on sophisticated systems to manage, process, and analyze data from various vendors23. However, the high overhead costs associated with on-site ICT infrastructure such as energy consumption, cooling, security, and system updates create significant operational expenses24. As a result, commissioning ICT infrastructure for each project becomes financially unfeasible, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which make up a substantial portion of the construction sector25. Furthermore, internal computer capacity is often limited and upgrading to meet unexpected demands can be prohibitively expensive. Consequently, the construction industry remains one of the least digitalized, with many firms hesitant to adopt new technologies due to the substantial financial commitments required26. This hesitancy has contributed to a delay in the widespread adoption of emerging technologies like cloud computing27. Despite these challenges, the potential for intelligent computing to transform the construction industry is undeniable. Intelligent computing, which combines artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and big data analytics, is an emerging field that aims to create systems capable of learning and adapting over time28. These systems have the potential to solve complex problems across a variety of domains, including construction29. Small construction businesses stand to benefit from the automation capabilities offered by intelligent computing. Tasks such as scheduling, cost estimation, and project management could be automated, freeing up resources for small firms to focus on other crucial aspects of their operations, such as managing staff and building client relationships30. Moreover, intelligent computing has the potential to help small construction enterprises reduce their environmental impact by optimizing energy and water usage in projects, thus cutting carbon emissions and lowering energy costs31. By analyzing data from past projects, intelligent computing systems could also improve safety standards by identifying patterns that highlight potential hazards32. This could lead to the development of new safety protocols, reducing accidents and improving overall site safety. Despite the numerous advantages of intelligent computing, several barriers hinder its adoption by small construction firms. One of the most significant obstacles is the high initial investment required for implementing these technologies. Intelligent computing systems often require specialized hardware and software, which can be costly to acquire and maintain33. For small businesses operating on tight budgets, justifying the expense of such an investment can be difficult, especially when the return on investment (ROI) may not be immediately apparent. The lack of experience with advanced technology is another barrier34. Many small construction firms lack in-house IT teams or technical expertise, making it difficult to adopt and integrate intelligent computing systems effectively35. The complexity of the construction industry further complicates the adoption of these technologies, as small businesses may struggle to navigate the technical intricacies involved in implementing and maintaining such systems36. Another critical barrier concerns data integration and quality. Intelligent computing systems rely heavily on high-quality data to function effectively, but construction projects often suffer from fragmented and inconsistent data collection practices as shown in Fig. 2. This lack of standardized data can undermine the effectiveness of intelligent computing solutions, which are only as good as the data they rely on37. Data security and privacy concerns also play a role in the reluctance to adopt intelligent computing in the construction sector38. Many small construction firms are wary of entrusting sensitive project data to external systems, particularly cloud-based platforms, due to fears about data breaches or unauthorized access39. These concerns, combined with the high costs and lack of expertise, create significant barriers to the widespread adoption of intelligent computing in small construction enterprises40. While intelligent computing offers significant benefits for small construction firms, including improved efficiency, cost savings, and enhanced safety, several barriers must be addressed to facilitate its adoption41. These include high initial investment costs, lack of in-house expertise, data integration and quality issues, and concerns about data security and privacy42. To overcome these challenges, small construction firms may need targeted solutions that offer cost-effective, scalable options for adopting intelligent computing technologies43. Additionally, increased awareness and education about the potential benefits of these technologies, as well as the development of industry-specific solutions, may help to accelerate their integration into the construction sector44. By addressing these barriers, intelligent computing could play a key role in modernizing the construction industry and driving improvements in project outcomes.

Another obstacle to the widespread application of intelligent computing is data integration and quality45. For intelligent computing systems to work effectively, high-quality, integrated data is necessary. Despite this, small construction companies frequently have poorly connected data silos. It may thus be challenging to gather and integrate the data required for intelligent computing systems to operate46. The adoption of intelligent computing is further hampered by privacy and security concerns. Sensitive information, including client and project data, is frequently collected and processed in intelligent computing systems47. Small construction businesses must carefully evaluate the security and privacy concerns when implementing intelligent computing technology. Notwithstanding the difficulties, small construction companies can use a variety of tactics to get over the obstacles to using intelligent computing48. Developing connections with IT service providers is one tactic. As seen in Fig. 3, IT service providers could be able to assist small construction companies with the knowledge and tools required to create and oversee intelligent computing systems49.

Another approach is to use cloud-based intelligent computing systems. The adoption of cloud-based intelligent computing technologies may reduce the initial cost and skill requirements of on-premises systems50. Another approach for small construction businesses to get started is to use intelligent computing solutions for tasks such as cost estimates and project scheduling51. This might help them make a business case for more investment and become more comfortable with the technology52. Finally, small construction enterprises must focus on improving the quality and consistency of their data. As a result, utilizing and deploying intelligent computing technologies will be more straightforward53. When using intelligent computing technology, small construction businesses should also implement appropriate security and privacy safeguards to protect their data54. Small construction businesses can leverage this new technology to overcome the barriers to intelligent computing adoption by using these strategies. Previous research has highlighted numerous key impediments to the application of intelligent computing systems at various project phases55. There are, however, measures that might assist small construction enterprises in beginning to address these problems. Another option is to employ intelligent computing systems hosted in the cloud. Table 1identifies restricted data availability and high startup expenses as constraints, cloud-based technologies may assist small businesses by decreasing data storage and infrastructure needs56. This might also help with scalability concerns in many design and construction projects.

Modular technologies that allow customization need to be recognized as a barrier during design may be provided via cloud systems57. Using intelligent computing solutions throughout the building stage for tasks like cost projections and project scheduling, is another way for small construction businesses to get started. This might increase comfort levels with technology by helping to demonstrate ROI and financial gain, regardless of cultural concerns58. Another way to support intelligent adoption is to concentrate on enhancing data quality at every stage. Six major obstacles to using intelligent computing solutions for sustainable building at different project stages design, construction, and operations are evaluated in Table 2. During the design phase, the complexity and customization barrier is recognized as a challenge because of the project requirements59. Research is needed on how to adapt tools to different stakeholder expectations and design restrictions in a flexible way. Tools that are customizable and adaptable might help with this. Problems with data quality and integration are emphasized for construction projects where the absence of standard formats may make on-site data collection problematic60. Integration of design and construction data was identified as a research requirement. Standardized data sharing guidelines and APIs might help get beyond this barrier61. Due to the high initial costs of new technology and the inclination of certain small businesses toward traditional methods, there are cultural and economic barriers throughout both the construction and operating phases62. Using decision support to illustrate real ROI use cases may boost adoption rates. Because of economies of scale, cloud-based shared databases may result in lower costs. Restricted data access has been shown to impede machine learning at every level, even though ethical data usage norms are still in their infancy. To preserve intellectual property and gather anonymized historical data, businesses require incentives. The large variety of project scopes led to the identification of scalability problems in both design and construction63. Future research should examine flexible scaling options. Open interoperability standards and microservices-based architectures may help with this. When it comes to setting priorities for research and development to lower adoption barriers at different stages of the building lifecycle, the chart is a smart place to start.

Identification of factors through literature

Intelligent computing has been widely discussed in studies related to the construction industry, highlighting its potential to improve productivity, safety, and decision-making64. However, there is a gap in the literature regarding the specific challenges that small-scale construction projects face when adopting intelligent computing technologies65. While the benefits of intelligent computing are well recognized, the barriers to its implementation in smaller projects remain underexplored66. This section reviews relevant research and identifies key obstacles preventing the widespread use of intelligent computing in small-scale building projects67. Small-scale construction projects often struggle with limited resources, including inadequate funding, poor infrastructure, and a shortage of skilled workers. Tight budgets make it difficult for small projects to allocate funds for the upfront costs associated with implementing intelligent computing68. Furthermore, these projects may require additional technical expertise to develop, manage, and maintain intelligent computing systems, which are often unavailable in small firms69. These resource constraints are significant barriers to the adoption of advanced technologies in the sector. Data management and accessibility also pose challenges70. Construction projects generate large volumes of data, but small projects may struggle to collect and manage this data effectively due to short project durations, irregular data collection practices, and organizational divides. Inconsistent data quality and lack of integration between systems can undermine the effectiveness of intelligent computing applications69. Additionally, ethical and privacy concerns are crucial when handling data in intelligent computing systems71. According to a survey, 80% of construction professionals express concerns about the potential misuse of sensitive data. Small-scale construction projects may lack the resources and expertise required to establish robust data privacy protocols, making the adoption of intelligent computing even more challenging72. Economic factors also play a role in the slow adoption of intelligent computing. Demonstrating a clear return on investment (ROI) is often difficult for small projects, as they may have limited data and resources to quantify the financial benefits of implementing such technologies68. The challenge of proving ROI can deter small construction firms from investing in intelligent computing systems, even when the long-term advantages are apparent. Cultural resistance to change is another significant barrier in the construction industry73. Many small-scale construction projects are hindered by a conservative mindset and a reluctance to embrace new technologies. This aversion to change can slow the integration of intelligent computing systems, as decision-makers may be hesitant to adopt technologies that disrupt established practices. Finally, integration presents a substantial challenge74. Small construction projects often rely on multiple software tools and platforms, making it difficult to integrate intelligent computing systems into existing workflows. The technical expertise and resources required to manage such integration can be overwhelming for small firms65. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive understanding of the specific obstacles faced by small-scale construction projects73. By recognizing and addressing these issues, stakeholders can develop targeted strategies to facilitate the adoption of intelligent computing, ultimately improving decision-making, productivity, and project outcomes.

Methodology

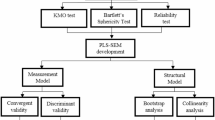

There are three primary stages to this inquiry. To determine the biggest barriers to integrating intelligent computing in small-scale building projects, the first step comprises reviewing the literature. Quantitative analysis and hypothesis testing are used in the second phase to examine the connections between the barriers that have been discovered and how they affect the effective implementation of intelligent computing. To verify proposed linkages and obtain a better knowledge of how the obstacles interact and affect the application of intelligent computing in small-scale building projects, the last step uses structural equation modeling. A flowchart showing the study’s sequential evolution through these three phases is shown in Fig. 4.

Survey design, data collection, and validity assessment

A structured survey was developed to assess barriers to intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects. The questionnaire, based on a comprehensive literature review, was validated through expert consultations and a pilot test. A 5-point Likert scale was used to quantify responses. Of the 230 questionnaires distributed, 143 valid responses were received (65% response rate), aligning with sample size norms in similar studies. To ensure methodological rigor, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) validity and reliability assessments were conducted. Convergent validity was confirmed using Average Variance Extracted (AVE > 0.50) and Composite Reliability (CR > 0.70). Discriminant validity was verified through the Fornell-Larcker criterion, and internal consistency was supported by Cronbach’s alpha values (> 0.70). Goodness-of-fit indices, including SRMR (< 0.08) and NFI (> 0.90), affirmed the model’s adequacy. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) identified key implementation barriers using principal component and common factor analysis. Eigenvalues > 1 and scree plot analysis determined factor retention. Factor loadings guided interpretation, revealing structural relationships among barriers. These analyses strengthened hypothesis testing and enhanced the study’s analytical foundation.

The study collected 143 valid responses out of 230 distributed questionnaires, yielding a 65% response rate. The sample size aligns with previous empirical studies on intelligent computing in construction. For instance, Bello, Adeyemo82used 120 responses, while Hong, Choi83 analysed 150 responses in similar research contexts, demonstrating the adequacy of our sample.

Additionally, the sample size was verified using Cochran’s formula for proportion-based population sampling:

where:

-

Z = 1.96Z = 1.96Z = 1.96 (for 95% confidence level).

-

p = 0.5p = 0.5p = 0.5 (maximum variability).

-

e = 0.08e = 0.08e = 0.08 (margin of error).

The calculated sample size required for reliable inference is approximately 150, which is comparable to our collected responses (143), confirming statistical sufficiency. Future studies may expand the sample for broader generalizability.

PLS structural model

A structural model analysis was conducted in addition to EFA and PLS-SEM. The study’s five structural model analysis hypotheses were put to the test via the bootstrap analysis. The dataset is resampled using the bootstrap process to assess the significance levels and standard errors of the model parameters. To test hypotheses and estimate model parameters, the process creates bootstrap samples. The O, M, STDEV, t-statistics, and p-values for each hypothesis were determined using bootstrap analysis. While the original sample value is the dataset estimate, the sample means, and standard deviation are derived from the resampled bootstrap datasets. P-values and t-statistics were computed to assess the estimated coefficients. P-values represent the probability of obtaining a value as extreme as the observed estimate under the null hypothesis, whereas t-statistics display the ratio of the estimated coefficient to its standard error. This establishes the importance of the model variable relationships. In this study, assumptions were tested using bootstrap analysis. The study evaluated structural model links, computed t-statistics and p-values, and estimated standard errors. By providing a solid statistical foundation for analyzing data and drawing conclusions, the bootstrap approach enhances the validity and reliability of hypothesis testing.

Predictive relevance

Structural model analysis was used to investigate predictive relevance (Q2). Q2 evaluates the predictive strength and relevance of the model by comparing the prediction performance of its endogenous components to a straightforward method. The variance explanation of the model’s exogenous constructs is represented by the Q2 value of each endogenous construct. It demonstrates the prediction ability of the model. If Q2 is high, the model provides meaningful predictions and captures relationships between variables. Q2 evaluated how well the structural model predicted endogenous construct variation. The Q2 data were compared to the simple mean model, which assumes that the dependent variable’s meaning is the best predictor. Compared to basic mean models, structural models have superior predictive performance, as evidenced by their higher Q2 values. The evaluation of Q2 aids in the forecasting of result characteristics for intelligent computing in small-scale building projects. It evaluates the predictive power of the model and aids in determining the usefulness of the connections in the structural model. By looking at Q2, this study explores the relationships between the variables and the usefulness of the model in forecasting and elucidating the relevant outcomes Fig. 5.

Results and analysis

Demographic details

The demographic profile of the 143 respondents is summarized in Table 3 below. The participants varied in educational background, professional experience, age, and occupation, providing a comprehensive perspective on the adoption of intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects.

Exploratory factor analysis

The item-underlying factor relationship strength is displayed in Table 4. EFA factor loadings show how important each item is in relation to the given factors. Most of the items had factor loadings greater than 0.6, indicating a close relationship with their factors. With a factor loading of 0.917, CC-CC1 has a good correlation with Factor 1 (Intelligent Computing - Critical Challenges). With high factor loadings of 0.902, 0.845, and 0.795, respectively, CC-LA1, CC-LA2, and CC-LA3 showed a strong correlation with Factor 2 (Intelligent Computing - Limited Availability). Two variables, CC-EP3 and CC-.

EC3, were removed from additional research because they failed to meet the minimum criteria. Cross-loading errors or low factor loadings suggest a poor or erratic relationship with any one factor. The strength and direction of item-factor relationships are shown by EFA factor loadings. If the item’s factor loading is high, it is an excellent predictor of the factor. These results aid in determining and assessing the challenges associated with using intelligent computing in small-scale building projects. To evaluate an item’s relevance to factors, factor loadings are crucial. To ensure that the selected items have a strong relationship with their components and are reliable indicators of the challenges being studied, EFA analysis employs a minimum criterion of 0.6.

PLS measurement model development

For each idea, the convergent validity studies’ Cronbach’s alpha (CA), average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) are displayed in Table 5. These measures establish internal consistency and dependability as well as the convergent validity of the measurement model. Internal consistency is measured by Cronbach’s alpha (CA), which shows how reliable each construct’s pieces are. Cronbach’s alpha promotes internal consistency. Item correlations are used by composite reliability (CR) to assess construct consistency. Over 0.7 CR is considered acceptable. The fluctuation of the concept in relation to measurement errors is evaluated using AVE. As AVE rises, convergent validity rises as well, suggesting that idea components vary widely. Convergent validity and internal solid consistency. Cronbach’s alpha ratings range from 0.713 to 0.865, indicating that most structures have strong internal consistency. Values for composite reliability are higher than 0.7. As indicated by the AVE values of 0.631 to 0.846, the constructs capture more variance than measurement errors. With these AVE values, most ideas exhibit convergent validity. The study did not use CC-DI3 (Data Quality and Integration 3) because of low factor loading or issues with cross-loading. Thus, the Data Quality and Integration construct is made up of CC-DI1 and CC-DI2. The measuring model’s validity and reliability are supported by the constructs’ convergent validity and internal consistency, which show that they capture the intended concepts.

Table 6 displays the results of the concept discriminant validity Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) analysis. By comparing correlations across constructs to average correlations within the same concept, the HTMT ratio assesses discriminant validity. The construct correlations to construct average correlations ratio and HTMT values are displayed. If the value is less than 0.85, the constructions are different. Diagonal values are disregarded since they compare a construct with itself. Construct discriminant validity is demonstrated by the HTMT scores that are below the diagonal. These two constructions are distinct as the HTMT score of 0.505 between DI (Data Quality and Integration) and CC (Complexity and Customization) is less than 0.85. Discriminant validity is also suggested by the HTMT scores for several concept pairs, including EC (Economic and Culture) and EP (Ethical and Privacy Concerns), EP and LA (Limited Data Availability), and EC and LA. Despite being significantly more significant, the HTMT values between DI and EC, DI and EP, and DI and SI (Scalability and Integration) still meet the 0.85 requirement, indicating sufficient discriminant validity. The results of the HTMT analysis in Table 5 demonstrate that the research’s components are distinct and not closely related, and they also exhibit discriminant validity. This implies that every construct represents a unique barrier to the application of intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted to identify latent structures in the dataset. Factor retention was determined using eigenvalues (> 1) and scree plot analysis, with high-loading items guiding interpretation. The extracted factors revealed key barriers to intelligent computing adoption. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) validated the measurement model. Convergent validity was confirmed through Average Variance Extracted (AVE > 0.50), Composite Reliability (CR > 0.70), and standardized factor loadings (> 0.60). Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. These results confirm the robustness of the factor structure and the reliability of the constructs, supporting further hypothesis testing.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, which is considered a more robust method than the Fornell-Larcker criterion for detecting discriminant validity issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). HTMT values below 0.85 indicate adequate discriminant validity. These figures demonstrate the degree of correlation between each variable and the desired construct as well as the potential for cross-loading onto other constructs. Variables load more on their intended construct than others. Complexity and Customization variables such as CC-CC1, CC-CC2, and CC-CC3 have higher loadings on the CC construct (0.727, 0.825, and 0.826) than other constructs. Complexity and customization have a high correlation with these characteristics. Additionally, the correlations between other elements and their intended structures are more remarkable. Variables in the Data Quality and Integration construct (CC-DI1 and CC-DI2) load more brilliantly on the DI construct (0.901 and 0.872) than variables in other constructs. A similar pattern may be seen in the following factors: Scalability and Integration, Ethical and Privacy Concerns, Economic and Culture, and Limited Data Availability. Construct validity is demonstrated by the variables’ alignment with their intended constructs. The cross-loading values of other structures are moderate. The discriminant validity of the dimensions indicates that they represent different barriers to the use of intelligent computing in small-scale building projects. The construct and discriminant validity of the measurement model are demonstrated by the cross-loading values in Table 7, which also support the relationships between the variables and their constructs.

The study examined the relationships between the dependent construct (CCI, or Intelligent Computing Implementation) in Table 8 and the independent constructs (CC, DI, EC, EP, LA, and SI). The O, M, STDEV, t-statistics, and p-values for each hypothesis. The acceptance or rejection of hypotheses is decided by statistical analysis. While rejected hypotheses imply a non-significant association, accepted hypotheses demonstrate a meaningful relationship between independent and dependent components. Except for H5 (Limited Data Availability -> Intelligent Computing Implementation), all the hypotheses were accepted in this study. Accepted hypotheses: These assumptions are supported by the t-statistics and p-values, which show that these distinct constructs have a significant impact on the research’s use of intelligent computing. Table 9 presents the results of hypothesis testing that demonstrate the impact of constructs on the implementation of intelligent computing. The accepted hypotheses highlight important factors that encourage the adoption of intelligent computing in the field under investigation.

The strength of the latent construct-observed indicator correlations is shown by the route loadings and p-values in Fig. 6. These numbers have an impact on the linkages’ strength and the degree to which the indicators evaluate their structures. To ascertain construct connections and the most significant markers for each construct, researchers might employ p-values and route loadings. The validity and reliability of the measurement model as well as the structural model are clarified by this study. The measurement model in PLS-SEM and the path loadings between latent constructs and observable indicators along with the p-values. The relationships among the identified barriers and their impacts on intelligent computing implementation are summarized in the structural equation modeling (SEM) diagram (Fig. 6). The diagram highlights statistically significant paths, demonstrating the critical roles of complexity, data quality, economic factors, and ethical concerns. It also underscores the weaker influence of limited data availability within this context.

Route loadings between latent components and indicators. The connections between measurable variables or items and unobserved constructs (factors or variables) are illustrated by these route loadings. Path loadings display the direction and strength of the link. They demonstrate how closely structures and indicators correspond. Path loadings as arrows connecting indicators and structures. Association significance is shown by path loading T-statistics. A more significant construct-indicator relationship is shown by higher T-values.

Predictive relevance Q2

The predicted relevance analysis of the model for the implementation of intelligent computing is displayed in Table 9. The sum of squares for the dependent variable is the model’s overall variance in Intelligent Computing Implementation. 4968.000 is the total. The initial squares of the dependent variable are the SSO value. It assesses variations in the implementation of intelligent computing without taking model predictions into account. 3900.123 is the SSO. The difference between projected and basic Intelligent Computing Implementation values is known as the sum of squares of errors (SSE), and it is used to evaluate the model’s unexplained variance or prediction errors. The Q2 value, which is 1 minus SSE/SSO, evaluates the predictive ability of the model. It calculates the proportion of variation in Intelligent Computing Implementation that the model accounts for. Q2 in this study is 0.215, indicating that 21.5% of the variation in Intelligent Computing Implementation can be explained by the model. The model may have predictive value if it can account for a large portion of the variance in Intelligent Computing Implementation. Unaccounted-for variances or prediction errors persist in the model. To increase the model’s accuracy and forecasting capacity, more research may be necessary.

Following Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the factor structure of the measurement model. Factor loadings, Average Variance Extracted (AVE > 0.50), Composite Reliability (CR > 0.70), and model fit indices (χ²/df < 3, CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08) confirmed the construct validity of the measurement model before proceeding with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). CCI is a second-order latent construct derived from multiple first-order constructs, including Complexity and Customization (CC), Data Quality and Integration (DI), Economic and Cultural Factors (EC), Ethical and Privacy Concerns (EP), Limited Data Availability (LA), and Scalability and Integration (SI). Each of these first-order constructs was measured using reflective indicators, which were validated through EFA and CFA. To mitigate multicollinearity, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were examined, ensuring that all constructs had VIF < 5, indicating that multicollinearity was not an issue. The structural model was tested using bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to validate the hypothesized relationships.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the challenges associated with adopting intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects. A mixed-methods approach was used, combining literature review, quantitative analysis, and structural equation modeling to explore the relationships between intelligent computing deployment and the identified obstacles. The study’s results offer valuable insights into the factors influencing the successful implementation of intelligent computing in the construction industry. The first hypothesis (H1) proposed a positive relationship between Intelligent Computing Implementation (CCI) and Complexity and Customization (CC). The data confirmed this hypothesis with a statistically significant positive correlation (β = 0.327, t = 9.848, p < 0.001), indicating that as complexity and customization increase, the likelihood of successfully implementing intelligent computing also rises. This finding supports previous studies that emphasize the importance of addressing the challenges and customization requirements when installing advanced technologies. The second hypothesis (H2) suggested a favorable relationship between CCI and Data Quality and Integration (DI). This hypothesis was strongly supported, with the analysis showing a significant positive association (β = 0.389, t = 14.534, p < 0.001). This indicates that improving data quality and enhancing integration with data sources are crucial for successful intelligent computing deployment. It highlights the importance of effective data management and integration strategies in optimizing the potential of intelligent computing systems. The third hypothesis (H3) examined the connection between CCI and Economic and Cultural Factors (EC). The results confirmed a positive association (β = 0.295, t = 7.85, p < 0.001), suggesting that a supportive organizational culture and favorable economic conditions are essential for the adoption of intelligent computing in small-scale building projects. Firms need to cultivate a culture that embraces technological innovation while aligning financial incentives to support the integration of new technologies. The fourth hypothesis (H4) explored the relationship between CCI and Ethical and Privacy Concerns (EP). The study found a statistically significant positive association (β = 0.319, t = 8.963, p < 0.001), emphasizing the importance of addressing privacy and ethical issues in the use of intelligent computing. To alleviate concerns and build trust in these technologies, organizations must prioritize developing comprehensive ethical frameworks, data protection protocols, and privacy policies. The fifth hypothesis (H5) proposed a relationship between CCI and Limited Data Availability (LA). However, this hypothesis was not supported, with the analysis showing a weak and statistically insignificant relationship (β = 0.041, t = 0.558, p = 0.577). This suggests that data availability may not be a major obstacle to implementing intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects. Further research could explore this relationship in more detail and examine other factors that may influence the availability of data. The sixth hypothesis (H6) assessed the connection between CCI and Stability and Integration (SI). The study found a significant positive correlation (β = 0.267, t = 6.519, p < 0.001), supporting the hypothesis. This highlights the importance of scalable and adaptable solutions for the successful integration of intelligent computing systems. Organizations should focus on developing scalable architectures and efficient integration methods to enable smooth deployment and integration of artificial intelligence technologies into existing systems. Overall, the study’s findings provide valuable insights into the challenges of using intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects. The results demonstrate that factors such as complexity, data quality and integration, economic and cultural challenges, ethical and privacy concerns, and scalability significantly influence the successful implementation of intelligent computing. These findings have practical implications for construction firms, highlighting the key issues that need to be addressed for effective technology adoption. However, the study has some limitations. The cross-sectional research design provides only a snapshot of the relationships between variables, and future research could use longitudinal methodologies to gain a deeper understanding of the challenges associated with intelligent computing adoption in the construction sector. Additionally, future studies could explore other variables that may affect the implementation process. This research contributes to the existing literature by identifying and analyzing the barriers to the adoption of intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects. To overcome these challenges, a structured approach is required, starting with identifying key obstacles such as economic limitations, cultural resistance, and data quality issues. Addressing these barriers can lead to the successful implementation of intelligent computing. One potential strategy is to use modular tools that offer scalable solutions tailored to the specific needs of small-scale construction projects. Transitioning to cloud-based systems can reduce high upfront infrastructure costs and improve data accessibility across stakeholders. Additionally, improving data quality through standardized collection methods and better integration practices can ensure reliable insights for decision-making. By addressing these challenges, small-scale construction projects can enhance operational efficiency, sustainability, and project outcomes through intelligent computing technologies.

Conclusion

This study explored the challenges of implementing intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects, investigating the relationships between various barriers and the adoption of intelligent computing through a thorough literature review, quantitative analysis, and structural equation modeling. The findings shed light on the key factors that influence the successful adoption of intelligent computing within the construction industry. Several significant obstacles were identified, including complexity and customization, data quality and integration, economic and cultural factors, ethical and privacy concerns, limited data availability, scalability and integration issues. The study revealed that complexity and customization requirements were statistically and positively correlated with the effective use of intelligent computing, suggesting that meeting these specific needs is essential for successful implementation. Additionally, the research found a strong positive correlation between intelligent computing adoption and challenges related to scalability, privacy and ethics, economic and cultural conditions, and data integration and quality. However, no significant relationship was observed between the availability of data and the adoption of intelligent computing, indicating that other factors may play a more crucial role in small-scale projects. The results of this study contribute to a deeper understanding of the barriers to implementing intelligent computing in the construction sector, emphasizing that addressing issues like complexity, data quality, privacy, scalability, and integration is crucial for successful technology adoption. These findings offer valuable insights for organizations in the construction industry, providing guidance on overcoming these obstacles and enhancing their ability to adopt intelligent computing technologies. Overcoming these challenges has the potential to improve overall project outcomes, streamline decision-making, and increase operational efficiency. However, it is important to note the limitations of the study. The findings may not be applicable in other contexts as the research was conducted within a specific setting. Additionally, the use of a cross-sectional methodology provides only a snapshot of relationships at a particular moment, limiting the understanding of long-term effects. Future research could build on this work by using longitudinal studies to explore the sustained impacts of intelligent computing in construction, and by examining how geographical and contextual factors influence its implementation in small-scale projects.

Limitations and future research: practical strategies

While this study provides valuable insights into the challenges of adopting intelligent computing in small-scale construction projects, its focus on China limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique economic, cultural, and regulatory context of China may differ from that of other regions, which could influence the applicability of the results. Future research should include cross-regional or international comparisons to examine how these barriers may manifest in different settings. Expanding the study to diverse geographic locations would offer a broader understanding of the challenges and help develop strategies that are globally relevant. Additionally, this study relied on cross-sectional data, which limits the ability to assess the long-term effects of intelligent computing adoption. A cross-sectional design captures only a snapshot at one point in time and may not account for changes over the long term, such as shifts in organizational culture or technology adaptation. Future studies could address this limitation by using longitudinal methods to track the ongoing impact of intelligent computing solutions. This approach would provide a deeper understanding of how barriers evolve and how proposed solutions contribute to long-term success in small-scale construction projects. To overcome the identified barriers and improve the adoption of intelligent computing, stakeholders should consider several practical strategies. Transitioning to cloud-based systems is critical for small construction enterprises, as it reduces the high upfront costs associated with traditional IT infrastructure. Cloud systems also offer scalability, easier integration, and better data accessibility, which supports effective collaboration among project stakeholders. Improving data management practices is equally important. Organizations should adopt standardized protocols for data collection and integration to ensure consistency and reliability. This would address data quality issues that often hinder the use of intelligent computing. Resistance to change is a significant challenge that can be addressed by fostering a culture of innovation and openness. Training programs, workshops, and leadership initiatives can help stakeholders understand the benefits of intelligent computing and encourage their support for its adoption. Modular tools are another useful solution. Their flexibility and scalability make them ideal for addressing specific project needs, especially in resource-limited environments. Building strategic partnerships with IT service providers and industry experts can also help small firms gain the technical expertise and resources needed for successful implementation. These collaborations can reduce costs and share the risks associated with adopting new technologies. By adopting these strategies, stakeholders can overcome barriers to intelligent computing and unlock its potential to improve efficiency, sustainability, and project outcomes in small-scale construction projects outcomes.

Data availability

Data associated with the study will be available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Change history

13 October 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23126-4

References

Rane, N. Integrating leading-edge artificial intelligence (AI), internet of things (IOT), and big data technologies for smart and sustainable architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry: Challenges and future directions. Engineering and Construction (AEC) Industry: Challenges and Future DirectionsSeptember 24, 2023. (2023).

Calautit, K. & Johnstone, C. State-of-the-art review of micro to small-scale wind energy harvesting technologies for building integration. Energy Conversion and Management: X, : p. 100457. (2023).

Hwang, J. M. et al. Identifying critical factors and trends leading to fatal accidents in small-scale construction sites in Korea. Buildings 13 (10), 2472 (2023).

Shang, G., Low, S. P. & Lim, X. Y. V. Prospects, drivers of and barriers to artificial intelligence adoption in project management. Built Environ. Project Asset Manage. 13 (5), 629–645 (2023).

Bachar, R. et al. Optimal allocation of safety resources in small and medium construction enterprises. Saf. Sci. 181, 106680 (2025).

Alshahrani, R. et al. Establishing the fuzzy integrated hybrid MCDM framework to identify the key barriers to implementing artificial intelligence-enabled sustainable cloud system in an IT industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 238, 121732 (2024).

Aziz, S., Kumar, P. & Khan, A. Assessing the impact of digital supply chain management on the sustainability of construction projects. Rev. Bus. Econ. Stud. 12 (3), 60–73 (2024).

Bamgbose, O. A., Ogunbayo, B. F. & Aigbavboa, C. O. Barriers to Building information modelling adoption in small and medium enterprises: Nigerian construction industry perspectives. Buildings 14 (2), 538 (2024).

Jayawardana, J. et al. Key Barriers and Mitigation Strategies Towards Sustainable Prefabricated construction–a Case of Developing Economies (Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 2024).

Kineber, A. F. et al. Modeling the impact of overcoming the green walls implementation barriers on sustainable Building projects: A novel mathematical partial least squares—SEM method. Mathematics 11 (3), 504 (2023).

Martin, H. et al. Validating the relative importance of technology diffusion barriers–exploring modular construction design-build practices in the UK. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res., : pp. 1–21. (2024).

Cheng, Q. et al. Leveraging BIM for sustainable construction: benefits, barriers, and best practices. Sustainability 16 (17), 7654 (2024).

Byers, B. & De Wolf, C. QR code-based material passports for component reuse across life cycle stages in small-scale construction. Circular Econ., : pp. 1–16. (2023).

Al Naimat, A. & Liang, D. Substantial gains of renewable energy adoption and implementation in Maan, Jordan: A critical review. Results Eng., : p. 101367. (2023).

Datta, S. D. et al. Benefits and barriers of implementing Building information modeling techniques for sustainable practices in the construction industry—A comprehensive review. Sustainability 15 (16), 12466 (2023).

Nguyen, T. D. & Adhikari, S. The role of Bim in integrating digital twin in Building construction: A literature review. Sustainability 15 (13), 10462 (2023).

Ghansah, F. A. & Edwards, D. J. Digital technologies for quality assurance in the construction industry: current trend and future research directions towards industry 4.0. Buildings 14 (3), 844 (2024).

Omole, F. O., Olajiga, O. K. & Olatunde, T. M. Challenges and successes in rural electrification: a review of global policies and case studies. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 5 (3), 1031–1046 (2024).

Tran, H. V. V. & Nguyen, T. A. A review of challenges and opportunities in BIM adoption for construction project management. Eng. J. 28 (8), 79–98 (2024).

Olanrewaju, O. I. et al. Modelling the relationship between Building information modelling (BIM) implementation barriers, usage and awareness on Building project lifecycle. Build. Environ. 207, 108556 (2022).

Bello, S. A. et al. Cloud computing in construction industry: use cases, benefits and challenges. Autom. Constr. 122, 103441 (2021).

Ngcobo, K. et al. Enterprise Data Management: Types, Sources, and real-time Applications To Enhance Business performance-a Systematic Review (Systematic Review| September, 2024).

Atkinson, E. et al. Challenges in the adoption of mobile information communication technology (M-ICT) in the construction phase of infrastructure projects in the UK. Int. J. Building Pathol. Adaptation. 40 (3), 327–344 (2022).

Lam, P. T. et al. Data centers as the backbone of smart cities: principal considerations for the study of facility costs and benefits. Facilities 39 (1/2), 80–95 (2021).

Koralun-Bereźnicka, J. & Gostkowska-Drzewicka, M. Trade credit policies in the construction industry: A comparative study of Central-Eastern and Western EU countries. Int. J. Manage. Econ., 2024(online first).

Junejo, A. K. et al. Adaptive speed control of PMSM drive system based a new sliding-mode reaching law. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35 (11), 12110–12121 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Practical adoption of cloud computing in power systems—Drivers, challenges, guidance, and real-world use cases. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 13 (3), 2390–2411 (2022).

Javaid, M. et al. Evolutionary trends in progressive cloud computing based healthcare: ideas, enablers, and barriers. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 3, 124–135 (2022).

Adeusi, O. C. et al. IT standardization in cloud computing: security challenges, benefits, and future directions. World J. Adv. Res. Reviews. 22 (05), 2050–2057 (2024).

Toufaily, E., Zalan, T. & Dhaou, S. B. A framework of blockchain technology adoption: an investigation of challenges and expected value. Inf. Manag. 58 (3), 103444 (2021).

Selesi-Aina, O. et al. The future of work: A Human-centric approach to AI, robotics, and cloud computing. J. Eng. Res. Rep. 26 (11), 62–87 (2024).

Shehu, Z., Endut, I. R. & Akintoye, A. Factors contributing to project time and hence cost overrun in the Malaysian construction industry. J. Financial Manage. Property Constr. 19 (1), 55–75 (2014).

Shelden, D. R. et al. Data standards and data exchange for Construction 4.0, in Construction 4.0. Routledge. pp. 222–239. (2020).

Shin, Y. et al. A formwork method selection model based on boosted decision trees in tall Building construction. Autom. Constr. 23, 47–54 (2012).

Shvets, Y. & Hanák, T. Use of the internet of things in the construction industry and facility management: usage examples overview. Procedia Comput. Sci. 219, 1670–1677 (2023).

Aati, K. et al. Analysis of road traffic accidents in dense cities: geotech transport and ArcGIS. Transp. Eng., : p. 100256. (2024).

Abuhussain, M. A. et al. Integrating Building Information Modeling (BIM) for optimal lifecycle management of complex structures. in Structures. Elsevier. (2024).

Alotaibi, B. S. et al. Building information modeling (BIM) adoption for enhanced legal and contractual management in construction projects. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15 (7), 102822 (2024).

Althoey, F. et al. Influence of IoT Implementation on Resource Management in Construction. Heliyon, (2024).

Elmousalami, H. H. Artificial intelligence and parametric construction cost estimate modeling: State-of-the-art review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 146 (1), 03119008 (2020).

Khan, A. M., Alaloul, W. S. & Musarat, M. A. The Carbon Footprint of Net Zero Buildings: A Critical Review. in 4th International Conference on Data Analytics for Business and Industry (ICDABI). 2023. IEEE. (2023).

Khan, A. M., Alaloul, W. S. & Musarat, M. A. A Critical Review of Digital Value Engineering in Building Design Towards Automated Constructionp. 1–46 (Environment, 2024).

Khan, A. M. et al. Python: An Automation Tool for Unlocking Innovation and Efficiency in the AEC Sector. in. 4th International Conference on Data Analytics for Business and Industry (ICDABI). 2023. IEEE. (2023).

Khan, A. M. et al. Internet of things (IoT) for safety and efficiency in construction Building site operations. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 28914 (2024).

Khan, A. M. et al. Optimizing energy efficiency through Building orientation and Building information modelling (BIM) in diverse terrains: A case study in Pakistan. Energy 133307, p (2024).

Khan, A. M. et al. BIM integration with XAI using LIME and MOO for automated green Building energy performance analysis. Energies 17 (13), 3295 (2024).

Maglad, A. M. et al. Bim-based energy analysis and optimization using insight 360 (case study). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, pe01755 (2023).

Musarat, M. A. et al. A survey-based approach of framework development for improving the application of internet of things in the construction industry of Malaysia. Results Eng., : p. 101823. (2024).

Musarat, M. A. et al. Substitution of workforce with robotics in the construction industry: A wise or witless approach. J. Open. Innovation: Technol. Market Complex., : p. 100420. (2024).

Musarat, M. A. et al. Automated monitoring innovations for efficient and safe construction practices. Results Eng. 22, 102057 (2024).

Noghabaei, M. et al. Trend analysis on adoption of virtual and augmented reality in the architecture, engineering, and construction industry. Data 5 (1), 26 (2020).

Pan, X. et al. BIM adoption in sustainability, energy modelling and implementing using ISO 19650: A review. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15 (1), 102252 (2024).

Sajjad, M. et al. BIM-driven energy simulation and optimization for net-zero tall buildings: sustainable construction management. Front. Built Environ. 10, 1296817 (2024).

Sajjad, M. et al. BIM implementation in project management practices for sustainable development: partial least square approach. Ain Shams Eng. J., : p. 103048. (2024).

Waqar, A. et al. Challenges of blockchain implementation in construction. J. Eng. 2024 (1), 2442345 (2024).

Waqar, A. et al. Analyzing the impact of holistic Building design on the process of lifecycle management of Building structures. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 29020 (2024).

Waqar, A. et al. Limitations to the BIM-based safety management practices in residential construction project. Environ. Challenges. 14, 100848 (2024).

Waqar, A. et al. Sustainable leadership practices in construction: Building a resilient society. Environ. Challenges. 14, 100841 (2024).

Waqar, A., Khan, A. M. & Othman, I. Blockchain empowerment in construction supply chains: enhancing efficiency and sustainability for an infrastructure development. J. Infrastructure Intell. Resil. 3 (1), 100065 (2024).

Waqar, A. et al. BIM in green building: enhancing sustainability in the small construction project. Clean. Environ. Syst., : p. 100149. (2023).

Waqar, A. et al. Complexities for adopting 3D laser scanners in the AEC industry: structural equation modeling. Appl. Eng. Sci. 16, 100160 (2023).

Waqar, A. et al. Integration of passive RFID for small-scale construction project management. Data Inform. Manage. 7 (4), 100055 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. BIM-based architectural analysis and optimization for construction 4.0 concept (a comparison). Ain Shams Eng. J. 14 (6), 102110 (2023).

Ibeh, C. V. et al. A review of agile methodologies in product lifecycle management: bridging theory and practice for enhanced digital technology integration. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 5 (2), 448–459 (2024).

Hodson, E. et al. Evaluating social impact of smart City technologies and services: methods, challenges, future directions. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 7 (3), 33 (2023).

Nilashi, M. et al. Critical data challenges in measuring the performance of sustainable development goals: solutions and the role of big-data analytics. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 5 (3), 1–36 (2023).

Aldoseri, A., Al-Khalifa, K. N. & Hamouda, A. M. Re-thinking data strategy and integration for artificial intelligence: concepts, opportunities, and challenges. Appl. Sci. 13 (12), 7082 (2023).

Zhu, S. et al. Intelligent computing: the latest advances, challenges, and future. Intell. Comput. 2, 0006 (2023).

Akanfe, O., Lawong, D. & Rao, H. R. Blockchain technology and privacy regulation: reviewing frictions and synthesizing opportunities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 76, 102753 (2024).

Niaz, M. & Nwagwu, U. Managing healthcare product demand effectively in the Post-Covid-19 environment: navigating demand variability and forecasting complexities. Am. J. Economic Manage. Bus. (AJEMB). 2 (8), 316–330 (2023).

Aithal, P. Super-Intelligent Machines-analysis of developmental challenges and predicted negative consequences. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Manage. Lett. (IJAEML). 7 (3), 109–141 (2023).

Sompolgrunk, A. et al. An integrated model of BIM return on investment for Australian small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Eng. Constr. Architectural Manage. 30 (5), 2048–2074 (2023).

Albahri, A. S. et al. A systematic review of trustworthy and explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare: assessment of quality, bias risk, and data fusion. Inform. Fusion. 96, 156–191 (2023).

Bammidi, T. R. et al. The crucial role of data quality in automated Decision-Making systems. Int. J. Manage. Educ. Sustainable Dev. 7 (7), 1–22 (2024).

Tomar, M. & Periyasamy, V. The role of reference data in financial data analysis: challenges and opportunities. J. Knowl. Learn. Sci. Technol. ISSN. 1(1) (online), 2959–6386 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Advanced controls on energy reliability, flexibility, resilience, and occupant-centric control for smart and energy-efficient buildings—a state-of-the-art review. Energy Build., : p. 113436. (2023).

Šestak, M. & Copot, D. Towards trusted data sharing and exchange in agro-food supply chains: design principles for agricultural data spaces. Sustainability 15 (18), 13746 (2023).

Muhammad, D. & Bendechache, M. Unveiling the Black Box: A Systematic Review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Medical Image Analysis (Computational and structural biotechnology journal, 2024).

Bouchetara, M., Zerouti, M. & Zouambi, A. R. Leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) in public sector financial risk management: innovations, challenges, and future directions. EDPACS 69 (9), 124–144 (2024).

Polancos, R. V. & Seva, R. R. A risk minimization model for a multi-skilled, multi-mode resource-constrained project scheduling problem with discrete time-cost-quality-risk trade-off Engineering Management Journal, 2024. 36(3): pp. 272–288.

Rane, N. & Cost Integrating Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) for Smart Construction Schedule, Cost, Quality, and Safety Management: Challenges and Opportunities. Quality, and Safety Management: Challenges and OpportunitiesSeptember 16, 2023. (2023).

Bello, S. A. et al. Effect of age, impaction types and operative time on inflammatory tissue reactions following lower third molar surgery. Head Face Med. 7, 1–8 (2011).

Hong, J. et al. Virtual reality-based analysis of the effect of construction noise exposure on masonry work productivity. Autom. Constr. 150, 104844 (2023).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Project Administration, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing: W.Z., H.F.I.; Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Software, Validation, Data Curation, Writing – original draft: W.Z., K.O.V., V.O.V., K.I., H.F.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

“This study involved participants for data collection using LIDAR technology in construction management. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Professional Design and Research Institute, China Architecture Design & Research Group, Beijing, 101100, China. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study, ensuring their voluntary participation and understanding of the research objectives.”

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in the name of authors Zonghui Wang, Olga Veniaminovna Kalugina, Olga Vladimirovna Volichenko & Ivan Khalil, which were incorrectly given as Wang Zonghui, Kalugina Olga Veniaminovna, Volichenko Olga Vladimirovna & Khalil Ivan respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Kalugina, O.V., Volichenko, O.V. et al. Sustainability in construction economics as a barrier to cloud computing adoption in small-scale Building projects. Sci Rep 15, 11329 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93973-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93973-8